Abstract

A growing number of countries are moving to scale up interventions for prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV in maternal and child health services. Similarly, many are working to improve access to paediatric HIV treatment. This paper reviews national programme data for 2004–2005 from low-and middle-income countries to track progress in these programmes. The attainment of the UNGASS target of reducing HIV infections by 50% by 2010 necessitates that 80% of all pregnant women accessing antenatal care receive PMTCT services. In 2005, only seven of the 71 countries were on track to meet this target. However PMTCT coverage increased from 7% in 2004 (58 countries) to 11% in 2005 (71 countries). In 2005, 8% of all infants born to HIV positive mothers received antiretroviral prophylaxis for PMTCT, up from 5% in 2004, though only 4% received cotrimoxazole. 11% of HIV positive children in need received antiretroviral treatment in 2005. In 31 countries that had data, 28% of women who received an antiretroviral for PMTCT also reported receiving antiretroviral treatment for their own health. Achieving the UNGASS target is possible but will require substantial investments and commitment to strengthen maternal and child health services, the health workforce and health systems to move from pilot projects to a decentralised, integrated approach.

Résumé

Un nombre croissant de pays tentent d’étendre la prévention de la transmission du VIH de la mère à l’enfant (PTME) dans les services de santé maternelle et infantile. De même, beaucoup s’emploient à améliorer l’accès au traitement pédiatrique du VIH. Cet article cherche à déterminer les progrès accomplis par les programmes nationaux de 2004-2005 dans des pays à revenu faible ou intermédiaire. Pour atteindre l’objectif de la session extraordinaire de l’Assemblée générale, à savoir réduire de 50% les infections par le VIH d’ici à 2010, il faut que 80% des femmes enceintes consultant pour des soins prénatals reçoivent des services de PTME. En 2005, sept seulement des 71 pays étaient dans les temps pour réaliser cet objectif. Néanmoins, la couverture de la PTME est passée de 7% en 2004 (58 pays) à 11% en 2005 (71 pays). En 2005, 8% des nourrissons exposés au VIH recevaient une prophylaxie antirétrovirale pour la PTME, contre 5% en 2005, même si 4% seulement prenaient du cotrimoxazole. En 2005, 11% des enfants séropositifs recevaient des antirétroviraux. Dans les 31 pays disposant de données, 28% des femmes ayant pris un antirétroviral pour la PTME avaient aussi reçu une thérapie antirétrovirale pour leur propre santé. Il est possible d’atteindre l’objectif de la session extraordinaire, mais des investissements substantiels et un engagement ferme seront nécessaires pour renforcer les services de santé maternelle et infantile, et pour faire passer les soignants et les systèmes de santé de projets pilotes á une approche décentralisée et intégrée.

Resumen

En un creciente número de países se están iniciando intervenciones de ampliación para la prevención de la transmisión materno-infantil (PTMI) del VIH en los servicios de salud materno-infantil. Asimismo, muchos de estos están esforzándose por mejorar el acceso al tratamiento pediátrico del VIH. En este artículo se analizan los datos del programa nacional, en 2004–2005, para que los países de bajos y medianos ingresos tracen los avances en estos programas. A fin de lograr el objetivo de la UNGASS de disminuir el índice de infecciones por VIH en un 50% para el año 2010, es necesario que el 80% de todas las mujeres embarazadas que accedan a la atención antenatal reciban servicios de PTMI. En 2005, sólo siete de los 71 países estaban al día para lograr este objetivo. Sin embargo, la cobertura de PTMI aumentó del 7% en 2004 (58 países) al 11% en 2005 (71 países). En 2005, el 8% de todos los recién nacidos que se calculó habían sido expuestos al VIH recibió profilaxis antirretroviral para la PTMI, un aumento del 5% en 2004, aunque sólo un 4% recibió cotrimoxazol. El 11% de los niños VIH-positivos necesitados recibieron tratamiento antirretroviral en 2005. En 31 países donde existían datos, el 28% de las mujeres que recibieron un antirretroviral para la PTMI también informaron recibir tratamiento antirretroviral para su propia salud. Aunque es posible lograr el objetivo de la UNGASS, se necesitarán considerables inversiones y compromisos para fortalecer los servicios de salud materno-infantil, los profesionales de la salud y los sistemas de salud para pasar de los proyectos piloto a una estrategia descentralizada e integrada.

At the end of 2005 there were an estimated 2.3 million children under the age of 15 living with HIV, 15 million orphans due to AIDS, 530,000 newly infected children (mainly through mother-to-child transmission) and 380,000 deaths as a direct result of AIDS.Citation1 The urgency of preventing these infections is undeniable and the knowledge and tools to do so exist. Many industrialised countries have all but eliminated paediatric HIV cases through a package of evidence-based interventions. Without such interventions, up to 40% of infants born to HIV positive mothers will acquire the virus during pregnancy or delivery, or through breastfeeding.Citation2 Eight years into the implementation of PMTCT programmes, many more countries are working to move from pilot to national PMTCT programmes and beginning to address the needs of children affected by HIV.

Global commitments, targets and goals

With Millennium Development Goals 4, 5 and 6, member states committed in 2000 to three important health goals for women and children: reduce child mortality, improve maternal health and halt and begin to reverse the spread of HIV and AIDS by 2015.Citation3 In countries with generalised epidemics, effective PMTCT and paediatric HIV care and treatment programmes can contribute to all three goals.

In 2001, through the UNGASS Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS, member states committed to reducing the proportion of infants with HIV by 20% by 2005 and 50% by 2010. To achieve these reductions, 80% of pregnant women accessing antenatal care should receive information, preventive services and treatment to reduce mother-to-child transmission of HIV, voluntary and confidential counselling and testing, access to treatment, especially antiretroviral therapy, and where appropriate, breastmilk substitutes and continuum of care.Citation4

In July 2005, the G8 nations called for the implementation of a package for HIV prevention, treatment and care, with the aim, if possible, of universal access to treatment for all who needed it by 2010.Citation5 In the same year, the Inter-Agency Task Team on PMTCT and Paediatric HIV assembled governments, donors and implementing partners at the PMTCT High Level Global Partners Forum in Abuja, Nigeria, which resulted in a Call to Action for the Elimination of HIV Infection in Infants and Children.Citation6 Late 2005 brought the global Unite for Children. Unite against AIDS campaign launched by UNICEF and UNAIDS to support universal access to treatment and address the impact of HIV and AIDS on children.Citation7

This paper reports the findings of a review of national programme data in 71 countries in 2005 and 58 in 2004 to put together quantitative and qualitative data on global, regional and country-level progress in PMTCT and paediatric HIV care and treatment. This paper also assesses the state of commitments that have been made to the millions of women and children infected with HIV each year.

Methods

Information was gathered using a standard questionnaire with closed questions, to collect quantitative and semi-qualitative national level PMTCT and paediatric HIV care and treatment data, aggregated from all sites and in-country implementing partners for the period January–December 2005. Data collected in 2005 using the same method for January–December 2004 were reviewed for trend analysis.Citation8 The questionnaire, developed by the UNAIDS Monitoring and Evaluation Reference Group, included national-level indicators that most countries have adopted and additional questions on programme and policy components.

Validation of the data was requested of Ministries of Health and/or national AIDS coordinating agencies. Follow-up interviews and clarification of data were carried out by UNICEF regional offices and headquarters in New York. A total of 103 questionnaires were returned from countries, of which 71 had complete data and were included in the final analysis. These accounted for 99% of the estimated number of HIV infected women giving birth in 2005 and 87% of the estimated HIV infected children under 15 years old in need of antiretroviral therapy. The 2004 data are aggregated from 58 countries, accounting for 86% of the estimated HIV infected women giving birth in 2004.

Intervention coverage was calculated using numbers collected from national programme data as numerators and global estimates of the number of people in need of services as denominators. Sources of estimates included World Population Reports of the UN Population Division for the number of births per year, and UNAIDS and WHO for the estimated number of HIV positive pregnant women and the number of children in need of antiretroviral therapy. Estimates were developed by the UNAIDS/WHO Working Group on Global HIV/AIDS and STI Surveillance, using standard methods based on recommendations of the UNAIDS Reference Group on Estimates, Modelling and Projections.Citation9

Limitations

The UN strategic approach to PMTCT includes four elements: primary prevention of HIV infection; prevention of unintended pregnancies among HIV-infected women; prevention of HIV transmission from HIV-infected women to their infants; and the provision of care and support to HIV-infected women and their infants and families. While this paper acknowledges the importance of a comprehensive approach that incorporates all four elements, the unavailability of data on the first two elements prohibited analysis of them. Work is ongoing to find methods to better capture the reality of primary prevention and family planning within the PMTCT context. Nevertheless, the lack of data is a red flag that these two key elements need strengthening.

Data based on health facility monitoring systems are subject to both under-and over-reporting and rely on the quality of national monitoring systems. For example, data on women accessing PMTCT through the private sector and delivering at home without a skilled birth attendant are often not captured in national programme data. Furthermore, since PMTCT and paediatric care and support programmes are still being rolled out, many countries do not yet have standardised national monitoring systems, and the number of pregnant women and children receiving treatment and care is often not recorded from all sites.

Another limitation is the comparability of data for 2004 and 2005 for trends, as additional countries have been included in the 2005 analysis; however, we are confident that the characteristics of the two samples of countries reporting are sufficiently constant.

Results

HIV testing and counselling

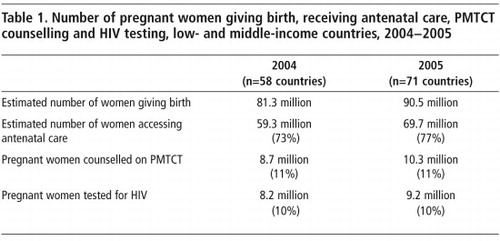

In the 71 countries, 90.5 million pregnant women are estimated to give birth annually. An estimated 99% of the 2.1 million HIV positive pregnant women giving birth in 2005 were among them. With 77% of pregnant women (70 million) in low-and middle-income countries having at least one antenatal care visit, the opportunity exists for them to be tested and counselled for PMTCT. Yet in the 71 countries in 2005, only 11% (10.3 million) were actually counselled on PMTCT and 10% (9.2 million) had an HIV test. Approximately 90% (9,230,300) of the women counselled were tested for HIV, a significant increase from the 50% testing uptake reported in 2002 from the initial 11 pilot projects.Citation10 The near universal acceptance of HIV testing among pregnant women who received counselling for PMTCT illustrates that women desire this important bridge to HIV treatment and prevention services. The fact that the vast majority of pregnant women did not receive testing and counselling for PMTCT exemplifies the many missed opportunities for ensuring the necessary services for healthy mothers and newborns. Similar trends were seen in 2004 (Table 1).

Identifying women in need of PMTCT services remains a challenge and is impeding many countries’ ability to prevent HIV infection in infants. In countries with generalised epidemics, the rapid expansion of provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling in maternal, newborn and child health (MNCH) settings and particularly in antenatal care and labour wards, has been an effective way to increase uptake of PMTCT services and contributes to normalising HIV as part of a basic MNCH service package. Botswana introduced the routine offer of HIV testing in 2004. Within three months, the proportion of pregnant women tested for HIV increased from 75% to 90%.Citation11 Governments in three-quarters of the countries analysed had begun to institutionalise provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling as part of MNCH services in all or some sites as of December 2005.

Countries must simultaneously strengthen social and legal frameworks and competencies, to support the implementation of provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling. This often requires the strengthening of community or social services and efforts to decrease the risk of social stigma, discrimination and violence against women.

The low level of HIV testing (3%) among pregnant women in West and Central Africa in 2005 was in part due to the fact that only a handful of countries in the region had begun to implement provider-initiated HIV testing. In contrast, in East and Southern Africa, provider-initiated HIV testing has become nearly universal and as a consequence nearly 90% of women counselled also received an HIV test. By comparison, only 42% of pregnant women in West and Central Africa counselled received an HIV test. With so few women being screened for HIV, few were identified and even fewer received PMTCT services in 2005.

Antiretroviral prophylaxis for mothers and babies

Despite missed opportunities, progress was made in 2005 with regard to PMTCT and scale-up efforts have started to show an impact. The proportion of HIV positive pregnant women receiving antiretroviral treatment for PMTCT increased from 7% in 2004 to 11%Footnote* in 2005, a more than 50% increase. The number of HIV exposed infants receiving antiretroviral prophylaxis rose from only 5% in 2004 to 8% in 2005. Nevertheless, fewer than 50% of women who tested positive for HIV at PMTCT sites in 2005 actually received antiretrovirals for PMTCT, exposing the fact that even when women with HIV are identified and initiated into the health care system, many are being lost along the way as well as their infants.

The delivery of ARV prophylaxis to infants has been equally challenging. In 2005, 8% (172,715 out of 2,153,881) of all infants estimated to be exposed to HIV received ARV prophylaxis as part of the PMTCT package, up from 5% in 2004. About a quarter of the infants born to women who received ARVs in 2005 slipped through the cracks of health systems and did not receive the necessary ARV prophylaxis needed at birth.

There must be a focus on strengthening overall health systems, particularly services for pregnant, delivering and post-partum women, in order for them to be fully able to identify and deliver PMTCT and treatment and care services to women and their families. In many countries MNCH services present the only opportunity for women to be provided with HIV prevention, care and treatment services. Formal integration of PMTCT within these services, focused on a continuum of care, coordinated efforts among service providers, and systematised follow up mechanisms have been shown to improve service uptake and decrease loss to follow up.Citation12

Central to strong health care systems are the skilled health personnel providing the necessary life saving services. The scale-up of quality health services for mothers and neonates must be improved; skilled birth attendants play a pivotal role for successful expansion of services. The shortage of health care workers in many parts of the world is one of the biggest barriers to reaching Millennium Development Goals 4, 5, and 6. Sub-Saharan Africa has been the hardest hit by the crisis. According to the WHO World Health Report 2006, Africa bears 24% of the global disease burden, including the vast majority of the HIV burden, but has only 3% of the health care workforce and 1% of the world’s financial resources.Citation13

Strong linkages between health services: key to scaling-up

Strengthening the linkages between sexual and reproductive health services and PMTCT must be guaranteed as PMTCT is scaled up in countries. The links between HIV and sexual and reproductive health are evident as more than 75% of HIV infections are acquired through sexual transmission or through vertical transmission.Citation14 In addition, the spread of HIV infection and sexual and reproductive ill-health are driven by many common root causes such as gender inequality, poverty and social marginalisation.

Preventing HIV infection in women must be a first priority in all PMTCT work. Millions of pregnant women around the world are HIV negative and need overall sexual and reproductive health and primary HIV prevention services. Such services must be accessible to all women and closely linked to PMTCT. Most governments have committed to this on paper but action is lagging.

Similarly, the rapidly expanding availability of antiretroviral therapy is making full care and treatment programmes a reality to many families around the world but linkages between PMTCT and treatment programmes need to be strengthened, including CD4 count monitoring and follow-up mechanisms between different services.

Antiretroviral therapy for mothers who qualify is the most effective PMTCT method of all, the best regimen to limit resistance and, of course, critical to keeping HIV infected mothers alive. As of December 2005 there was very little information on how many pregnant women had been assessed for eligibility. Forty-four of the 71 countries did not have national data on the number of HIV positive pregnant women assessed for CD4 cell counts, and very few women were assessed in the countries with data. Yet CD4 count is a useful indicator of the level of referrals and linkages taking place between traditional PMTCT services and services providing antiretroviral treatment, care and support. Large data gaps were similarly found regarding the number of HIV positive pregnant women receiving antiretrovirals for their own health; 40 of the 71 countries had no national data. It is estimated that about 15–25% of HIV positive pregnant women are in need of treatment.Citation15 Of the 31 countries that did report data, 28% of 82,633 women who received an antiretroviral for PMTCT also reported receiving antiretroviral treatment for their own health. However, some of the countries are providing full antiretroviral therapy for PMTCT and not necessarily for the mother’s own health; others do not have disaggregated data on what drugs are provided and the actual timing of the prescription, whether during pregnancy or after delivery, is not provided.

When antiretrovirals are not indicated, pregnant women need to be provided with a range of choices to prevent HIV infection in their infants, including more efficacious regimens going beyond single-dose nevirapine.Citation16

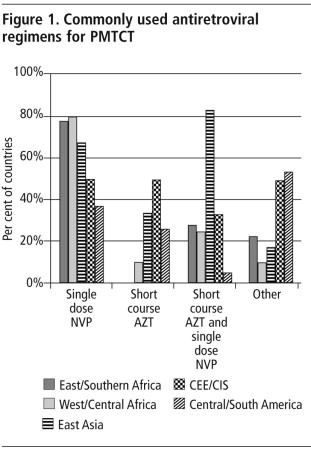

The majority of countries (66%) reported that single-dose nevirapine is still the most commonly used PMTCT antiretroviral regimen, including in most of the high burden countries. Single-dose nevirapine is reportedly the most common PMTCT regimen used in 80% of West and Central African countries, 78% of Eastern and Southern African countries and in India ().

Funding modalities and donor policies have often reinforced existing barriers to closer linkages, instead of removing them to supporting a health systems approach. While the need remains great for additional funds for HIV and AIDS, targeted financing which earmarks funds for specific vertical programmes makes it difficult for countries to strengthen and fully integrate HIV into existing maternal, newborn and child health services.Citation17 However, positive steps are being made by governments and other maternal and child health stakeholders in policy and financing initiatives in a number of countries, including Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, to better enable the integration of PMTCT into maternal, newborn and child health systems.

High disease burden regions

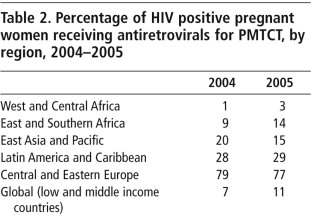

While many countries are beginning to scale up PMTCT programmes nationally, expansion of services remains low in many world regions. Countries with the highest burden of HIV have the lowest PMTCT service coverage (Table 2). In all regions except for Central Asia, Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Latin America and the Caribbean, the vast majority of women are not being tested and counselled on PMTCT and consequently not even aware of their HIV status – particularly in sub-Saharan Africa and India, where 95% of HIV infected pregnant women live.

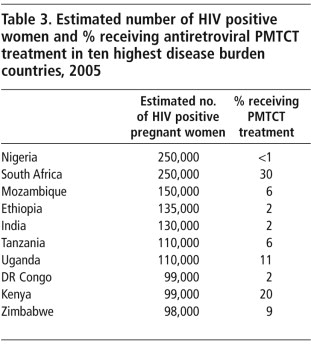

However, two of the highest disease burden regions, West and Central Africa and East and Southern Africa, were also the two regions where several countries are making noticeable progress. Over 50% more women had access to PMTCT services in East and Southern Africa in 2005 than the year before. South Africa doubled the percentage of all HIV positive women receiving treatment for PMTCT in 2005 and more than six times as many women in Swaziland had access to PMTCT services in 2005 than the year before. Although a handful of countries in West and Central Africa also saw some progress in 2005, it was far from adequate. The proportion of HIV positive pregnant womenFootnote* receiving antiretrovirals for PMTCT in the ten highest disease burden countries in the world, accounting for two-thirds of all mother-to-child HIV infections in 2005, are shown in Table 3. The Democratic Republic of Congo and Nigeria both report less than 1% and 2% PMTCT service coverage, respectively. PMTCT programmes urgently need to be expanded in these countries to reach the millions of women in need of services.

The geographical expansion of PMTCT and paediatric HIV care and treatment service points is a critical step in guaranteeing that all women and children have access to services. Services that are decentralised and fully integrated into maternal, newborn and child health facilities and lower levels of the health care system are necessary to ensure that HIV positive women and children are identified for treatment of their own. Globally, no more than a quarter of facilities providing antenatal care in 2005 also provided PMTCT services (Table 4).

National governments, however, are beginning to demonstrate a more significant commitment to the scale-up of services in the last few years. All 71 countries had established PMTCT programmes with national policies and strategies to guide implementation in 2005 and 32 of them had national PMTCT scale-up plans with population-based targets, as called for in the Abuja Call to Action. However, systems to implement scale-up plans remain inconsistent.

Global progress on PMTCT

To meet the UNGASS 2010, countries could be considered “on track” if at least 40% of all HIV positive women were receiving antiretrovirals for PMTCT by 2005, which means few countries were on track in 2005. Globally, only seven low-and middle-income countries of the 71 included in the analysis provided ARV prophylaxis to at least 40% of the estimated number of HIV positive women giving birth in 2005 (Table 5). On the other hand, a number of countries made significant progress in just one year from 2004 to 2005. With increasing resources, more managerial expertise and lessons learned, it is hoped that many more countries will get on track in the next few years.

Global progress on paediatric HIV care and treatment, 2005

Until PMTCT services reach all pregnant women infected with HIV, children will continue to be infected. The majority of children living with HIV and AIDS do not have access to any form of care or treatment even though they account for one in six of global AIDS-related deaths.Citation1 Without treatment, an estimated one-third of infants will die before their first birthday and half before the age of two.Citation19 Recent analysis has shown that infants infected perinatally are at particular risk of death from 2–6 months of life. Cotrimoxazole, a highly effective antibiotic for preventing pneumonia and other opportunistic infections, and early paediatric antiretroviral treatment are fundamental for prolonging the lives of many infected infants.Citation20–22

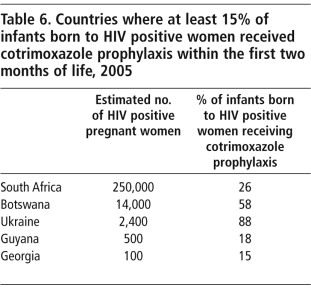

Provision of cotrimoxazole prophylaxis for infants born to HIV positive mothers and HIV positive children has been slow in many countries. Cotrimoxazole can reduce child mortality in HIV positive children by over 40%, and has been part of the standard of care for preventing pneumonia and other opportunistic infections since the early 1990s.Citation21 Because of the difficulty in diagnosing HIV infection in infants, WHO 2006 guidelines recommend that all infants born to mothers living with HIV should receive cotrimoxazole prophylaxis starting at 4–6 weeks of age (or at the first subsequent encounter with the health care system) and continue until HIV infection can be excluded and the child is no longer at risk. While many countries are beginning to adopt this policy, translation into practice remains a challenge. Coverage data for cotrimoxizale treatment for infants and children as an indicator have not been integrated into health and management information systems in most countries. However, where data were available, only 4% of HIV exposed children had received cotrimoxazole globally in 2005.

Currently there are a large proportion of HIV exposed and infected children lost to follow-up due to lack of established systems to find and track them. If a mother is tested and/or given treatment during antenatal visits, health care providers at labour and delivery need to be aware of her HIV status to provide the needed care at delivery, in the immediate post-natal period or as soon as possible in the first few months of life. Progress in this area is being made with many countries, such as Zimbabwe, working to improve follow-up of women and infants through revising child immunisation registries and child health cards, to help health care providers identify women and children requiring antiretroviral and cotrimoxazole treatment. In addition, by integrating cotrimoxazole into the basic health care package, countries can help to ensure that all exposed children are started on cotrimoxazole by six weeks.

Certain countries have effectively initiated HIV-exposed infants on cotrimoxazole (Table 6), e.g. in Ukraine 88% of infants born to HIV positive mothers were initiated on cotrimoxazole within two months of birth in 2005. Benin has the highest coverage in West and Central Africa with 10% of exposed infants receiving cotrimoxazole. Lao had the highest coverage in Asia with 14%.

Paediatric diagnostics

In order to scale up paediatric HIV treatment programmes sufficiently, children must be diagnosed at the earliest possible age. In 2005 only 2% of exposed infants received an HIV test in the first 18 months of life. The tests used to diagnose adults with HIV cannot be used to exclude HIV infection in children up to 18 months of age due to remaining maternal antibodies. But given that about a third of HIV positive infants die by 12 months and 50% by two years, it is unacceptable to wait until 18 months to perform a diagnostic HIV test in children.Citation19

Early diagnosis through virology testing is still not widely available in most low-and middle-income countries. In general, PCR tests are considered the gold standard for early diagnostic testing. Dried blood spots (DBS) on filter paper facilitate access to virological testing in that specimens can be easily collected, stored and transferred to centralised testing locations for analysis. The DBS technology makes it possible for blood samples in remote locations to be tested and allows countries to have a limited number of regional laboratories capable of performing high quality PCR. Nevertheless, in 2005, fewer than 2% of infants had access to early PCR testing with less than 25,000 children receiving a PCR test globally out of the 2.1 million who were HIV exposed.

Paediatric treatment

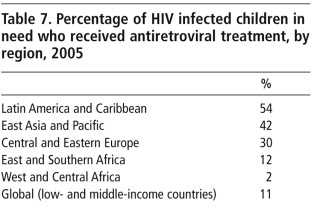

Children are not proportionately receiving the care, treatment and support they need to keep them healthy. The number of children receiving treatment remains inappropriately small with 11% of the estimated 780,000 children in need reported to have received antiretroviral treatment in 2005, with large regional variability (Table 7). Latin America and the Caribbean had the highest coverage, with 54% of positive children in need receiving antiretroviral treatment while West and Central Africa had only 2% coverage. Although children accounted for 12% of new HIV infections and 13% of all AIDS deaths, only 6% of the approximately 1.3 million people estimated to receive treatment in 2005 were children.Citation1

Whilst the global unmet need remained at approximately 90% for paediatric treatment in 2005, a number of countries made notable progress. The countries where at least 20% of children in need received antiretroviral treatment in 2005 were Rwanda (20%), El Salvador (21%), Guatemala (22%), Dominican Republic (23%), Peru (27%), Jamaica (33%), Paraguay (51%), Namibia (52%), Argentina (83%), Botswana (84%), Brazil and Thailand (>95% each). While the Latin America and Caribbean region is by far leading the way in terms of service coverage, it is home to only 3% of the estimated number of children in need of antiretroviral treatment globally (23,000 out of 780,000) and efforts need to be increased particularly in regions where the vast majority of cases exist.

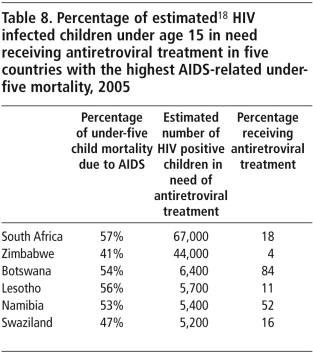

As most HIV positive children die before their fifth birthday, HIV is contributing strongly to increases in under-five mortality, reversing, in many countries, years of success in lowering child mortality.Citation23 The WHO estimates that in six countries in southern Africa, HIV and AIDS account for over 40% of all deaths in children under five (Table 8).Citation24 Urgent scale-up of PMTCT and paediatric HIV care and treatment is urgent in these countries.

Once PMTCT and paediatric HIV and AIDS care is available, involving families and communities is vital to increase demand, strengthen linkages between community and health services, support adherence to treatment and provide other necessary support. Partner-friendly approaches and existing community structures can play an important role identifying and referring pregnant women and children in need of PMTCT and other services often not available through the public health system, such as psycho-social and nutrition support.Citation12

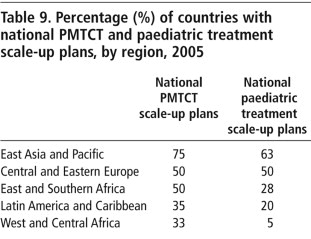

The Inter-Agency Task Team on PMTCT and Paediatric HIV needs to develop methodologies for setting national geographical service coverage according to epidemic typology and appropriate targets for providing care and treatment to all who need it. This will dictate how PMTCT and paediatric HIV care and treatment programmes are brought to scale in countries. The development of national paediatric scale-up plans lags behind the development of PMTCT scale-up plans in all regions. Only 23% of the 71 countries reported having paediatric scale-up plans for 2005 (Table 9). There continue to be limited infrastructure and skilled health personnel for the case management of HIV positive children; treatment is still limited to larger cities and towns and must be scaled up in a more decentralised manner.

Conclusion

This paper demonstrates that scale-up of PMTCT and paediatric HIV care and treatment programmes is gaining momentum in many countries, which is very encouraging as it demonstrates that low-and middle-income countries can provide these services in spite of the challenges that exist. The achievement of the UNGASS 2010 operational target is still possible but will require substantial investments and commitment to strengthen maternal, newborn and child health services, the health workforce and health systems. Learning from countries with successful programmes and in line with numerous global commitments, countries need to set ambitious population-based targets with the goal of eliminating HIV in children. This means moving from pilot projects to a decentralised, integrated, scaling-up approach within their specific epidemic typologies which empowers and builds the capacity of the health system at all levels.

Acknowledgements

This paper is written on behalf of the expanded Inter-Agency Task Team on PMTCT and Paediatric HIV. We thank Yves Souteyrand, Coordinator of Strategic Information, Department of HIV, WHO Geneva; Peter McDermott, Chief of HIV/AIDS Section, Programme Division, UNICEF New York; Jos Perriens, Coordinator, Prevention in the Health Sector, Department of HIV, WHO Geneva; and Charlie Gilks, Coordinator Care & Treatment Unit (ART), Department of HIV, WHO Geneva, for their support and input in this work.

Notes

* The 2005 PMTCT coverage figure in UNICEF’s 2006 Stocktaking Report was 9%, using the same programme data (numerators) as reported here; however, the denominators for calculating the coverage rate were updated, thus changing the overall global coverage figure.

* The estimates of numbers of HIV-infected pregnant women are based on methods developed by WHO, UNICEF and UNAIDS.Citation18.

References

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, World Health Organization. AIDS Epidemic Update, December 2006. 2006; UNAIDS/WHO: Geneva.

- UNAIDS. 2005 Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. 2005; UNAIDS: Geneva.

- UN Millennium Project. Investing in development: a practical plan to achieve the Millennium Development Goals. 2005; UN: New York.

- UNAIDS. Implementation of the declaration of commitment on HIV/AIDS: core indicators. 2006; UNAIDS: Geneva.

- G8 Gleneagles. The Gleneagles Communiqué. Gleneagles, 2005.

- World Health Organization. Call to action: elimination of HIV infection in infants and children. Proceedings of PMTCT High Level Global Partners’ Forum, Abuja. 2005; WHO: Geneva.

- UNICEF. Global campaign on children and AIDS: unite for children, unite against AIDS. At <www.unicef.org/uniteforchildren/index.html>. Accessed 1 May 2007

- PMTCT Report Card 2005: monitoring progress on the implementation of programmes to prevent mother to child transmission of HIV. UNICEF and WHO on behalf of the expanded Inter-Agency Task Team on PMTCT. 2005; UNICEF: New York.

- UNAIDS. Reference group on estimates, modelling and projections. At <http://www.epidem.org>. Accessed 1 May 2007

- UNICEF. PMTCT programme news. 2003; UNICEF: New York.

- Centers for Disease Control. Introduction of routine HIV testing in prenatal care: Botswana, 2004. Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 53(46): 2004; 1083–1086.

- MM Kane, TC Colton. Integrating SRH and HIV/AIDS services: Pathfinder International’s experience synergizing health initiatives. 2005; Pathfinder International: Boston.

- WHO. World Health Report 2006: Working together for health. 2006; WHO: Geneva.

- United Nations Population Fund. Glion call to action on family planning and HIV in women and children. 2004; UNFPA: New York.

- J Stover, N Walker, C Grassly, M Marston. Projecting the demographic impact of AIDS and the number of people in need of treatment: updates to Spectrum projection package. Sex. Transm. Inf. 82: 2006; 45–50.

- WHO. Antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infections in infants in resource-limited settings: towards universal access. 2006; WHO: Geneva.

- N Druce, A Nolan. The big missed opportunity: why haven’t maternal, newborn and child health services taken HIV into account for women and their children?. Reproductive Health Matters. 15(30): 2007; 190–201.

- WHO, UNICEF, UNAIDS. Towards universal access: scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector. Progress report. 2007

- ML Newell, H Coovadia, M Cortina-Borja. Mortality of infected and uninfected infants born to HIV-infected mothers in Africa: a pooled analysis. Lancet. 364: 2004; 1236–1243.

- E Marinda, JH Humphrey, PJ Iliff. Child mortality according to maternal and infant HIV status in Zimbabwe. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 26(6): 2007; 519–526.

- AS Walker, V Mulenga, D Ford. The impact of daily cotrimoxazole prophylaxis and antiretroviral therapy on mortality and hospital admissions in HIV-infected Zambian children. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 44: 2007; 1361–1367.

- WHO. Guidelines on cotrimoxazole prophylaxis for HIV related infections among children, adolescents and adults in resource-limited settings. 2006; WHO: Geneva.

- N Walker, B Schwartzlander, J Bryce. Meeting international goals in child survival and HIV/AIDS. Lancet. 360(9329): 2002; 284–289.

- WHO. Mortality: country fact sheets. 2006; WHO: Geneva.