Abstract

Although the majority of births in Mexico are attended by skilled birth attendants, maternal mortality remains moderately high, raising questions about the quality of training and delivery care. We conducted an exhaustive review of the curricula of three representative schools for the education and clinical preparation of three types of birth attendant – obstetric nurses, professional midwives and general physicians – National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) School of Obstetric Nursing; CASA Professional Midwifery School; and UNAM School of Medicine, Iztacala Campus. All curricular materials were measured against the 214 indicators of knowledge and ability in the International Confederation of Midwives (ICM) skilled attendant training guidelines. The CASA curriculum covered 83% of the competencies, 93% of basic knowledge and 86% of basic abilities, compared with 54%, 59% and 64% for UNAM Obstetric Nursing School and 43%, 60% and 36% for UNAM School of Medicine, respectively. Neither the Obstetric Nursing School nor the School of Medicine documented the quantity or types of clinical experience required for graduation. General physicians attend the most births in Mexico, yet based on our analysis, professional midwives had the most complete education and training as measured against the ICM competencies. We recommend that professional midwives and obstetric nurses should be formally integrated into the public health system to attend deliveries.

Résumé

La majorité des accouchements au Mexique bénéficient d’une assistance qualifiée. Pourtant, la mortalité maternelle demeure modérément élevée, ce qui soulève des questions sur la qualité de la formation et des soins obstétricaux. Nous avons étudié le curriculum de trois écoles représentatives pour l’enseignement et la préparation clinique de trois types de personnel obstétrical (infirmières en obstétrique, sages-femmes professionnelles et médecins généralistes): l’École de soins infirmiers obstétricaux de l’Université autonome du Mexique (UNAM), l’École de sages-femmes professionnelles CASA et l’École de médecine de l’UNAM, campus d’Iztacala. Tout le matériel pédagogique a été évalué par rapport aux 214 indicateurs de connaissances et d’aptitudes des directives de formation de la Confédération internationale de sages-femmes pour les accoucheuses professionnelles. Le curriculum CASA couvrait 83% des compétences, 93% des connaissances de base et 86% des aptitudes de base, contre 54%, 59% et 64% pour l’École de soins infirmiers obstétricaux UNAM et 43%, 60% et 36% pour l’École de médecine UNAM, respectivement. Ni l’École de soins infirmiers obstétricaux ni l’École de médecine n’informaient sur la somme ou les types d’expérience clinique requise pour obtenir le diplôme. Les médecins généralistes accouchent la plupart des femmes au Mexique, pourtant, d’après notre analyse, les sages-femmes professionnelles avaient suivi la formation la plus complète selon les critères de la Confédération internationale des sages-femmes en matière de compétences. Nous recommandons d’intégrer officiellement les sages-femmes professionnelles et les infirmières obstétricales dans le système de santé publique pour la surveillance des accouchements.

Resumen

Aunque la mayoría de los partos en México reciben atención calificada, la tasa de mortalidad materna continúa siendo moderadamente alta, lo cual plantea preguntas respecto a la calidad de la capacitación y la prestación de servicios. Realizamos una revisión exhaustiva de los currículos de tres escuelas representativas para la formación y preparación clínica de tres tipos de asistentes de partos – enfermeras obstétricas, parteras profesionales y médicos generales – la Facultad de Enfermería Obstétrica de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM); la Escuela de CASA de Partería Profesional; y la Facultad de Medicina de la UNAM, Recinto de Iztacala. Todos los materiales curriculares fueron medidos contra los 214 indicadores de conocimiento y capacidad, enumerados en las directrices de la Confederación Internacional de Matronas respecto a la capacitación en atención del parto calificada. El currículo de CASA abarcó el 83% de las aptitudes, el 93% del conocimiento básico y el 86% de las habilidades fundamentales, comparado con el 54%, 59% y 64% para la Facultad de Enfermería Obstétrica de la UNAM y el 43%, 60% y 36% para la Facultad de Medicina de la UNAM, respectivamente. Ni la Facultad de Enfermería Obstétrica ni la Facultad de Medicina documentaron la cantidad o los tipos de experiencia clínica exigidos para graduarse. Los médicos generales atienden la mayoría de los artos en México, pero, de acuerdo con nuestro análisis, las parteras profesionales contaban con formación y capacitación más completas, conforme a las aptitudes citadas por la Confederación Internacional de Matronas. Recomendamos que las parteras profesionales y enfermeras obstétricas se integren oficialmente al sistema de salud pública para atender partos.

The estimated maternal mortality ratio in Latin America and the Caribbean is 190/100,000 live births, lower than in other developing regions of the world yet still unacceptably high, with broad inequalities across the region. Between 1990 and 2000 it remained unchanged.Citation1 Mexico, like other countries in the region, has made only minor improvements in the maternal mortality ratio since the Millennium Development Goals were signed, yet over 90% of births are attended by physicians and other skilled attendants. The principal causes of maternal deaths in Mexico are toxaemia and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (32%), haemorrhage (22%), complications of the puerperium (10%) and abortion (8%).Citation2Citation3 Since 1990, maternal mortality has decreased in rural areas, but increased in urban areas; the highest rates are now found in states where 96–98% of deliveries are attended by skilled providers. While maternal mortality is a complex issue, this concentration of maternal deaths in areas well served by physicians raises concerns about the quality of training and subsequent care provided by them.

This study discusses the respective strengths and weaknesses of the educational programmes for three types providers of obstetric care in Mexico. These are professional midwives with a technical license, obstetric nurses and general physicians. Physicians with specialist training in obstetrics and gynaecology were not included because these providers have advanced training in obstetric care and do not attend the majority of births in Mexico. Ascertaining the quality of education is the first step in the assessment the potential of each of these groups of professionals to contribute to improvements in maternal and infant health in Mexico.

Background

The term “skilled attendant” refers to a health professional, whether midwife, nurse or doctor, who has been educated and trained to proficiency in the skills needed to manage normal (uncomplicated) pregnancies, childbirth and the immediate post-partum period, and in the management or referral of complications in women and newborns. An investigation by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO)Citation1 found that although approximately 75% of women giving birth in the region are attended by physicians, nurses and midwives who meet the definition of skilled birth attendant,Citation4 the fact that maternal mortality remains high probably indicates substandard care.

Mexico is representative of the PAHO findings. The static nature of maternal mortality in Mexico in recent years and the need for skilled attendants, especially in rural and poor areas, has led to a national conversation about how best to meet women’s needs. During the period 1994–1997, 61.5% of births were attended in the public sector, 21% in the private sector and 16% at home by midwives or other individuals.Citation2 Improvements in maternal mortality from the 1970s–80s were consistent with the increasing percentage of women attended by physicians and broad changes in the health care system.Citation5 Those changes included a 1968 decision that obstetric nurses would no longer attend deliveries in public hospitals and their place taken by physicians (Personal communication, Dr Patricia Uribe, Director, National Gender and Reproductive Health Center, Ministry of Health, Mexico, 8 May 2007). In 1974, 55% of births were attended by physicians and 40% by traditional midwives and nurses. By 1997, 82% of all deliveries in Mexico were attended by physicians and 15% by nurses or midwives. By 2002, 97% of births were attended by physicians, nurses or midwives,Citation2 but the moderately high maternal mortality ratio (64/100,000)Citation6 demonstrates that more work is needed if the Millennium Development Goals are to be met by 2015.Citation7

There is rural–urban variation in those who provide obstetric care. Thirty-three per cent of deliveries in rural areas were attended by nurses or traditional midwives from 1994–97, compared with 15% for the country as a whole.Citation2 Discrepancies in skilled attendance at birth also exist between the wealthier northern regions and the poorer, southern rural areas. In some poorer states, only 50% of women have skilled attendance in pregnancy and birth, and more maternal deaths might be expected to occur in those areas. However, from 1990 to 2002 (the same period in which reduction in maternal mortality was stalled) the proportion of maternal deaths in urban areas increased from 54% to 64% while the proportion of rural deaths decreased from 46% to 36%.

These facts raise questions about the quality of obstetric medical education and care in Mexico. In particular, since young pre-graduate and newly graduated physicians are providing the majority of basic health care in rural communities, including obstetric care, their preparation for this work is critically important. Often they work alone and in settings with minimal supervision from general or specialised staff physicians.

In addition to the physicians who provide most of the obstetric care in Mexico, there are two types of non-physician obstetric providers also currently being trained to attend births: professional midwives and obstetric nurses. The leading institution for training and education of midwives, and the only school whose graduates receive technical licenses, is the CASA Professional Midwifery School (CASA), a private school run by CASA, a non-governmental organisation (<www.casa.org.mx>). The school was launched in 1996 with the goal of producing young professionals with traditional and modern skills to work in rural areas. To date the graduates have been working independently for NGOs or in the private, not-for-profit hospital run by CASA. Graduates have also been hired by the government public health department in San Luis Potosi. There are five schools nationally that specialise in obstetric nursing,Citation8 all of which focus on training women’s health care clinicians to work primarily in a clinic or hospital setting, and all include education in direct provision of obstetric services.

The goal of this research was to analyse and compare the curricula of representative schools in Mexico for each of these three types of skilled birth attendant, and measured against the core competencies for skilled birth attendants as defined by the International Confederation of Midwives (ICM) and endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO).Citation9 The core competencies for skilled birth attendants are the international standard for provision of skilled, safe, professional care to childbearing women and their families. They reflect the essential knowledge, skills and behaviours for a provider of ante-partum, intra-partum, post-partum and neonatal care.

Methodology

The three representative education programmes, one for each provider type, were chosen with the assistance of the Mexican Ministry of Health and invited to participate. These were the CASA Professional Midwifery School in San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato, UNAM School of Obstetric Nursing in Mexico City and UNAM School of Medicine, Iztacala Campus, also in Mexico City, which trains physicians. UNAM School of Medicine is the largest trainer of physicians in the country, with over 1,200 students completing their course of studies in 2003,Citation10 and representative of general medical training offered throughout Mexico. UNAM Obstetric Nursing School, the largest in the country providing university-level training for obstetric nurses, had over 250 graduates in 2003. CASA Midwifery School accepted its first class in 1996 and in 2005, 15 students matriculated. CASA is much smaller than the other two programmes, but is the only school for professional midwives that has appropriate governmental approval.

The protocol was approved by the ethics and research committees at the Mexican National Institute of Public Health and the University of California at San Francisco. Each institution was contacted and a meeting was arranged with key personnel, including the Deans and Directors, to inform them of the design and intent of the evaluation. A letter of agreement was signed, and a contact person in each institution was assigned to provide all written curriculum materials and supporting documents. Interviews were conducted with faculty and the deans of UNAM School of Medicine Iztacala, and UNAM School of Obstetric Nursing, as well as the Director and faculty of CASA Midwifery School.

The respective curricula were reviewed using quantitative methods with inclusion of information gathered from the interviews. The purpose of the review was to determine whether or not each programme’s coursework contained critical elements necessary to provide proficient and humane independent labour and delivery care. A data collection tool was created based on the ICM Essential Competencies for Basic Midwifery Practice, Citation12 and included a list of the 214 competencies for skilled birth attendants adopted by WHO and the International Federation of Gynecologists and Obstetricians.Citation9 The 214 competencies are divided into six core competencies, each of which is divided into basic or additional knowledge and skills:

| • | general social sciences, public health skills and ethics; | ||||

| • | health education and services to promote healthy family life; | ||||

| • | antenatal care; | ||||

| • | labour and delivery care and emergencies; | ||||

| • | post-natal care; | ||||

| • | care from birth to two months of age. | ||||

It is expected that the basic knowledge and skills are applicable to all settings and the additional knowledge and skills can be adapted according to the specifics of each health system (see Table 1).

The two principal investigators (Walker, Cragin) and an additional expert carried out a comprehensive review of the documents provided by the three schools. All had relevant qualifications and experience, including in design and evaluation of curricula for nurse–midwifery education, participation in medical, public health and nursing education, and current obstetric and nurse–midwifery practice. Each was given primary responsibility for the evaluation of one of the school’s documents. After the initial reviews were completed, the group met to cross check for items not found by the initial reviewer. The forms were evaluated for the inclusion or omission of each specific competency. The three reviewers came to agreement on preliminary scores for each institution.

After the initial review was completed, each institution was sent a list of missing data and asked to provide, if possible, documentation of the missing content. Any additional documents provided by the institutions were then subject to the same process of review before a final score was calculated for each institution.

Results

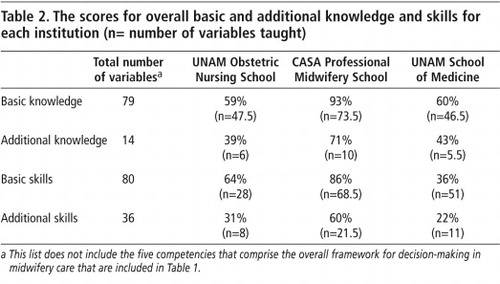

Overall results of the curricular review are presented in Tables 1 and 2 . Table 1 contains the score for each institution by competency. Table 2 contains the scores for overall knowledge and skills for each institution. Each programme is described in detail below.

UNAM School of Medicine

The school accepts students with high school (grade 12) education to matriculate for the six-year medical school programme based on qualifying entry examinations. The first two years consist of classroom-based learning in the basic medical sciences followed by clinic/hospital-based training in years three and four. This includes a six-week maternity rotation. The fifth year is an internship rotating between the different services of one hospital or clinic, and during the sixth year students are required to complete a year of social service (pasante year) comprised of clinical work in an assigned hospital, clinic or institution. Responsibility for and exposure to maternity care depends upon the type of services provided at the institutions in which students work.

Strengths

Iztacala’s curriculum uses an innovative approach which integrates basic science theory with corresponding clinical applications using a systems approach. The curriculum prepares generalist physicians. The basic science perspective is strong, with 100 credits devoted to coursework in this area. Programme objectives include the concept of “working partnership with patients”. The public health perspective is well defined and documented.

Limitations

This programme prepares generalists, and the content specific to the core obstetric competencies is limited and non-specific. Only 92.5 of the 214 indicators of necessary knowledge and skills for skilled birth attendance could be documented. The programme did not include coursework in psychology or mental health except for a module pertaining to substance abuse, and this was limited to alcoholism.

We were unable to verify that UNAM School of Medicine has any requirement for the type and number of supervised clinical experiences necessary for the development of the skills in the ICM Core Competencies. Neither a register of clinical experiences nor a standard for minimum experiences were found in the programme materials. Without these, we could not determine whether students were required to have a minimum number of supervised clinical experiences in obstetrics prior to graduation. During the interview with the Dean and faculty, a clear concern about the limited number of appropriate obstetric clinical sites was voiced. The quality of students’ clinical preparation in obstetrics is entirely dependent upon the experiences available in each clinical site. The sites are assigned by lottery without regard to student interest in any given specialty.

UNAM School of Medicine graduate doctors are expected to provide a full range of women’s health care services during the pasante year, including skilled birth attendance. The analysis leads to the conclusion that the curriculum lacks sufficient depth of theory and supervised clinical coursework to prepare physicians as skilled attendants at birth. Most remarkably, only six weeks of the five years are spent in obstetric rotations. The pasante year, in which the generalist students are expected to manage independently after a short period of orientation, lacks the type of close mentoring and follow-up necessary for the type of ongoing skill acquisition that results in proficient knowledge and safe obstetric practice.

UNAM Obstetric Nursing School

Obstetric nurses attend a five-year university programme. They are admitted after high school (grade 12), based on a competitive examination. The programme is comprised of four years of basic nursing training. The first two years consist of an overview of nursing practice and basic courses in anatomy, physiology and development. The third year is devoted to the nursing process and practice across the life span. The fourth year is focused on obstetrics and the final year is dedicated to social service. UNAM Obstetric Nursing School trains the majority of obstetric nurse graduates in Mexico, an of average 250 per year.Citation11

Strengths

The curriculum showed a strong focus on nursing theory, public health, psychosocial aspects of health, and maternal–child health education, including preparation for delivery, community health and home care. The programme had well-defined theoretical modules on the fetal-to-neonate transition, well baby care and patient education. Required clinical practice experiences include: insertion of IUDs immediately post-partum, nursing care of women in labour, nursing care of labour inductions, management of normal delivery, nursing care of patients in prenatal clinics, home visits, nursing care of the newborn (normal and high risk), and teaching childbirth education classes. Nursing actions are comprised of dependent (upon the orders of physicians) and interdependent (tasks that have been agreed to be within the scope of practice of a nurse) functions.

Limitations

Materials provided by the UNAM Obstetric Nursing School documented only 115.5 of the 214 indicators of necessary knowledge and skills. The curricular material provided did not include written material covering the content of the last semester of year four, during which management of obstetric complications is covered. An e-mail from the UNAM Obstetric Nursing School faculty asserted that this last semester addressed many of the missing core competencies, however no curricular documentation was provided for confirmation.

Courses are generally identified as “nursing care of” and do not emphasise independent management skills with respect to the process of data collection, assessment and diagnosis, plan of care (including consultation, collaboration and/or referral) or follow-up for ante-partum, intra-partum and post-partum care, family planning and newborn care. Since nurses “with training in obstetrics” are considered skilled providers by WHO and counted as such by the government of Mexico, it is important that they be provided with theoretical preparation and a decision-making framework for independent practice.

As with UNAM School of Medicine, numbers of required clinical experiences were not specified. Documentation of specific types of clinical experiences is not required and if gathered is kept by individual instructors. No documentation was provided to clarify whether students were given sufficient opportunities to acquire the skills defined by ICM. The curriculum does not articulate the process for teaching the degree of autonomy, independent problem-solving, critical thinking and inter-professional relationships that should be inherent in the role of obstetric nurse. Difficulty in obtaining appropriate and adequate clinical training sites was also voiced as a concern of the faculty and Dean at the Obstetric Nursing School.

UNAM Obstetric Nursing School devotes the last year of education and training to obstetrics. This concentration provides time for in-depth maternal health content and clinical training. The lack of availability of clinical experience in sites which promote independent management skills severely limits the number of graduates who can attain proficiency, however. We estimated that while UNAM Obstetric Nursing School graduates 250 students a year, only 50 have supervised clinical experience that supports autonomous practice upon graduation. There is insufficient documentation as to whether the graduates have the skills necessary for managing low risk ante-partum, intra-partum and post-partum care or of providing initial management, consultation and referral in emergency or high risk situations.

CASA Professional Midwifery School

Students are required to complete a secondary school (grade 9) education and pass an admission examination and interview prior to admittance. This three-year midwifery programme is comprised of a first year of basic sciences, a second year of nutrition, pharmacology, health education and introductory obstetrics courses, and a third year of advanced obstetric pharmacology and neonatal course work. Each year students are expected to participate in clinical care provided at the CASA hospital, which provides almost exclusively obstetric services.

Strengths

CASA represents a comprehensive programme that devotes three years to preparing graduate midwives, incorporating 83% of the ICM competencies. The programme provides a good base of health care sciences in the first year and then devotes the rest of the content to the acquisition of women’s health care knowledge and skills, including advocacy, health education and culturally relevant care. The curriculum is woman-and family-centred.

CASA scored the highest in the quantitative analysis, meeting 178.5 of the 214 specific knowledge and skill requirements. The curriculum is modelled after the Midwives Association of North America core competencies, which are similar to the WHO core competencies for skilled birth attendants. Theory and practical experience pertinent to ante-partum, intra-partum, post-partum care for the woman, and for the infant delivery, newborn and well baby care are integrated over the entire three-year period. The theory and clinical coursework progress in a logical manner from a foundation of basic science pertinent to maternal and child health, and include psycho-social issues, community health, culture, customs and traditional midwifery practices.

Unlike the curricula at the School of Obstetric Nursing and the Medical School, curriculum review revealed an emphasis on teamwork and interpersonal relationships. Senior students support junior students and all participate in community building with outside midwives. Clinical experiences include home and hospital settings. Until recently, the CASA hospital provided all hospital-based clinical training. Since July 2006, public hospitals also provide training. Clinical objectives are specified along with recommended numbers of experiences. The programme fosters teamwork and inter-personal relationships.

Limitations

There was limited content pertaining to high-risk obstetric management. Pharmacology course content pertinent to women’s health was not explicitly defined in the courses. The objectives did not explicitly incorporate a sequential process of critical thinking as a framework for consultation, co-management and referral in high risk situations. CASA’s greatest limitation may be its capacity. Unlike the volume of graduates produced by the Obstetric Nursing and Medical Schools, CASA has not had a graduating class larger than 10 students. This small class size allows for more hands-on experience but limits its ability to meet an increasing demand for trained professional midwives.

Discussion

In addition to the infrastructure needed for any type of safe obstetric care, the ability of skilled attendants to provide safe and humanistic care begins with their basic education and training. Without an education that includes both a didactic structure for learning the core scientific concepts of maternal and newborn care and the supervised clinical experiences necessary to attain the important skills, it is unlikely that an individual will be able to practise safely.

Each programme represents a unique approach to preparing skilled birth attendants, with varying degrees of accordance with required competencies as outlined by ICM. Thorough and impartial curriculum analysis depends on the ability to review very specific course goals and objectives with accompanying lecture and seminar content guides that together cohesively reflect and articulate the goals and objectives. While the missing content and activities may actually be included by all three programmes, the documentation was not always available in the materials provided, especially by UNAM Obstetric Nursing School and UNAM School of Medicine.

It is important to recognise that while CASA Midwifery School aims exclusively to prepare midwives to provide maternity care, UNAM School of Medicine and UNAM Obstetric Nursing School are graduating generalist physicians and nurses who require a range of skills for a variety of clinical situations apart from obstetrics, and both have curricula with clinical experiences that provide a good foundation for generalist nursing and medical practice.

In our evaluation, we sought documentation that verified the didactic structure and supervised clinical experiences for core and advanced midwifery knowledge and skills. WHO recognises the need to require those receiving a general nursing or medical education to have “specialist education and training, either during their pre-service education or as part of a post-basic programme of studies”.Citation9 However, the documentation provided by these programmes did not demonstrate the additional training needed to be able to manage “normal (uncomplicated) pregnancies, childbirth and the immediate postnatal period, and in the identification, management and referral of complications in women and newborns”.Citation9

Our evaluation demonstrates the need for improvements in the nursing and physician curricula to meet these requirements. Specifically, the nursing curriculum should focus on providing a foundation for independent clinical care. Basic and advanced clinical competencies should be defined and evaluated in a systematic manner. The number and type of clinical experiences leading to clinical competence should be documented. Coursework in life-saving skills for obstetric emergencies should be developed.

While each school must evaluate which of the competencies included under additional knowledge and skills ought to be in their curricula, those related to the prevention and identification, and treatment, stabilisation or referral of life-threatening conditions must be included. For example, none of the curricula contained content about active management of the third stage of labour nor discussed how to evaluate and use appropriate consultation or referral to the next higher level of care.

Future horizons for skilled birth attendants in Mexico

New physicians, even though they have finished their medical school course work, have limited supervised clinical training before their placement in rural communities. These new providers are frequently of a different social and linguistic background than the patients they serve or the traditional midwives who bring women to them. They work in situations of scarce material resources and without easy access to expert consultation and back-up for the high risk conditions they may encounter. These factors, in addition to the limitations found in the curriculum, hamper their effectiveness.

Evidence shows that nurses with midwifery skills and professional midwives can and do provide a high quality of maternity care in Mexico,Citation12 oftentimes to women from poor and vulnerable populations.Citation13 However, in Mexico there are currently barriers to practise for both these types of skilled providers that must be addressed.

The issues facing obstetric nursing in Mexico are complex and multi-level. Entry paths into nursing are diverse and unemployment rates are high, further complicating the discussion. While nearly 62% of nurses in Mexico have university trainingCitation14 nearly 50% of them are not employed.Citation15Citation16 Early in 2005, the Secretary of Health re-opened obstetric nursing positions in public hospitals, recognising that university-trained obstetric nurses have the potential to have a positive impact on the quality of labour and delivery care. The administrative details for implementing this new policy are still being refined. However, as we found, since pre-service clinical practice sites are extremely limited, due to resistance by hospital directors to nurses attending deliveries, it may be many years before a sufficient number of qualified obstetric nurses graduate to fill these positions. Creating job opportunities within hospitals will help address one of the many barriers to nurses working as skilled birth attendants.

Official acceptance of professional midwives has been difficult as traditional midwives who had no formal training are characterised in negative ways, ranging from ill-prepared and therefore dangerous, to superfluous to the health care system. Since post-partum haemorrhage and eclampsia are leading causes of maternal mortality, solutions aimed at improving the infrastructure so that rural women have rapid access to medical care are seen by some as more relevant than promoting the newer professional midwives to work in rural areas in the health care system.

While graduates of CASA have a historic connection to traditional midwives, their education and training provides the necessary level of knowledge and skills to enable them to be included in the ranks of skilled professionals at birth. This curriculum could be improved by strengthening aspects of pharmacology, increasing emphasis on emergency management, and providing explicit content on consultation with other members of the health care team, including negotiation skills and knowledge of scope of practice for each member of the team.

Professional midwives, in particular, may provide both a medically sound and culturally sensitive option in needy rural settings. However, professional midwives face many of the same obstacles facing obstetric nurses, including limited access to clinical practice sites, resistance by the medical establishment and few options for long-term steady employment, as the Secretary of Health does not have positions for midwives in public hospitals.

Implementation of a system of care that includes non-physician skilled attendants requires that policymakers at all levels of government support the necessary infrastructure changes. The Mexican Ministry of Health has taken two important steps in this direction by opening places for obstetric nurses and by providing the necessary approvals for CASA midwifery graduates to do their social service year in public hospitals. The next step for the Ministry is to begin to employ professional midwives and obstetric nurses in rural health clinics and marginalised urban clinics with a maternal death ratio above the national average. This intervention must be critically and rigorously evaluated in order to obtain evidence of its effectiveness, and if effective, the Ministry should support the opening of more professional midwifery schools.

We recommend that professional midwives and obstetric nurses should be formally integrated into the public health system to attend deliveries. To ensure the long-term success and sustainability of this policy, legislation is needed that defines an independent scope of practice for professional midwives and obstetric nurses, allowing them to care for women of childbearing age under their own licenses. The positions of professional midwife and obstetric nurse must be incorporated into the hospital staff registry and supported financially, both to legitimise them as professionals and facilitate hiring. Existing referral networks need to be strengthened and, as with any strategy to combat maternal mortality, the use of non-physician providers should be tailored to the setting, reflecting the distinct needs of urban vs. rural areas, and the physical and human resource differences between hospitals and clinics.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the University of California Institute for Mexico and the United States for funding this study. We are indebted to the directors, deans and faculty of the UNAM School of Obstetric Nursing, UNAM School of Medicine, Iztacala Campus, and CASA Professional Midwifery School for their collaboration. We appreciate the invaluable contributions of Susan J Leibel and Susanna Cohen.

References

- Pan American Health Organization. Health Statistics from the Americas. 2003 Edition, 2003; PAHO: Washington DC.

- Consejo Nacional de Población. Reproductive health indicators in the Mexican Republic. At: <www.conapo.gob.mx/00cifras/00salud.htm>. Accessed 30 April 2007

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Información. Databases on mortality 2002–2004. At: <www.inegi.gob.mx/est/default.aspx?c=2351>. Accessed 4 May 2007

- Pan American Health Organization. Profiling midwifery in the Americas: models of childbirth care. 2005; PAHO: Washington DC.

- J Frenk, J Sepúlveda, O Gómez-Dantés. Evidence-based health policy: three generations of reform in Mexico. Lancet. 362(9396): 2003; 1667–1671.

- WHO/UNFPA/UNICEF/World Bank. Reduction of Maternal Mortality. 1999; WHO: Geneva.

- Consejo Nacional de Población. Mexico ante los desafíos de desarrollo del Milenio. 2005; CONAPO: Mexico City.

- Declaration of the United Nation’s Millenium Development Goals. At: <www.un.org/milleniumgoals>. Accessed 2 May 2007

- Asociación Nacional de Universidades y Instituciones de Educación Superior. Catálogo de Carreras y Licenciaturas en Universidades y Institutos Tecnológicos: ANUIES: Mexico City, 2004. At: <www.anuies.mx/>. Accessed 26 April 2007.

- The joint WHO/ICM/FIGO statement on skilled attendants at birth. Midwifery. 21(1): 2005; 1.

- Asociación Nacional de Universidades y Instituciones de Educación Superior. Anuario Estadístico 2004: Población Escolar de Licenciatura y Técnico Superior en Universidades e Institutos Tecnólogicos. 2004; ANUIES: Mexico CityAt: <http://www.anuies.mx/>. Accessed 26 April 2007

- International Confederation of Midwives. Essential Competencies for Basic Midwifery Practice. At: <www.internationalmidwives.org/modules.php?op=modload&name=News&file=article&sid=27>. Undated. Accessed 4 May 2007

- D Walsh, SM Downe. Outcomes of free-standing, midwife led birth centres: a structured review. Birth. 31(3): 2004; 222–229.

- L Paine, J Lang, D Strobino. Nurse–midwife patient and visit characteristics. American Journal of Public Health. 89(8): 1999; 906–909.

- S Malvárez, C Castrillón. Overview of the nursing workforce in Latin America. Human Resources Development Series No.39. 2005; PAHO: Washington DC.

- G Nigenda, JA Ruiz, R Bejerano. University-trained nurses in Mexico: an assessment of educational attrition and labour wastage. Salud Pública de México. 48(1): 2005; 22–29.