Abstract

The occurrence of complications during pregnancy depends less on the degree of human development than differences in the way complications in pregnancy are detected and managed. It is the quick diagnosis and correct management that really contribute to the enormous differences in maternal mortality ratios between countries and regions. Understanding of the determinants of maternal mortality may be improved by studying cases of severe maternal morbidity. In this paper, various approaches to the concept of severe maternal morbidity and near-misses are discussed, and the relationship between these and maternal deaths. Although no consensus has been reached on a strict definition of near-miss or severe maternal morbidity, we show that the definitions used may be tailored to support diverse objectives, including monitoring progress, epidemiological surveillance and auditing of health care. We conclude that the versatility of the concept, the greater frequency of cases available for study and the possibility of interviewing the survivors of severe complications all support the value of studying severe maternal morbidity to help guide local efforts to reduce maternal mortality. Although this may almost be a reality in developed countries, it continues to represent an important and difficult challenge to overcome in places where its benefits would be most evident.

Résumé

L’apparition de complications pendant la grossesse dépend moins du degré de développement humain que des différences dans la détection et la gestion de ces cas. Ce sont le diagnostic rapide et la gestion adaptée qui contribuent réellement aux énormes différences entre le taux de maternité maternelle de pays et régions. L’étude des cas de grave morbidité maternelle peut aider à comprendre les facteurs de la mortalité maternelle. Cet article étudie plusieurs définitions du concept de grave morbidité maternelle et d’« échappée belle », et la relation entre ces cas et les décès maternels. Même s’il n’y a pas de consensus sur une définition stricte des « échappées belles » ou de la morbidité maternelle grave, nous montrons que les définitions utilisées peuvent être conçues de manière à soutenir différents objectifs, notamment le suivi des progrès, la surveillance épidémiologique et le contrôle des soins de santé. Nous en concluons que la versatilité du concept, la fréquence accrue de cas disponibles pour l’étude et la possibilité d’interroger les patientes ayant survécu sont autant d’arguments en faveur de l’étude de la morbidité maternelle grave pour guider les activités locales de réduction de la mortalité maternelle. Si c’est presque une réalité dans les pays développés, cela demeure un défi difficile à relever là où ses avantages seraient les plus évidents.

Resumen

La presencia de complicaciones durante el embarazo depende menos del grado de desarrollo humano que de las diferencias en la forma en que se detectan y manejan. Un diagnóstico rápido y manejo correcto contribuyen a las enormes diferencias en razones de mortalidad materna entre países y regiones. El estudio de casos de morbilidad materna grave ayuda a entender mejor los determinantes de la mortalidad materna. Este artículo trata de diversos enfoques respecto al concepto de la morbilidad materna severa y casos que casi conducen a la muerte, así como la relación entre estos y muertes maternas. Aunque no se ha establecido una definición estricta de dichos casos o de la morbilidad materna severa, se muestra que las definiciones utilizadas pueden adaptarse para apoyar diversos objetivos: el monitoreo de los avances, la vigilancia epidemiológica y la auditoría de los servicios de salud. Concluimos que la versatilidad del concepto, el aumento en casos disponibles para el estudio y la posibilidad de entrevistar a las sobrevivientes, apoyan el valor de estudiar la morbilidad grave para guiar los esfuerzos locales por disminuir la mortalidad materna. Aunque esto es casi una realidad en los países desarrollados, continúa siendo un gran reto difícil de vencer en lugares donde sus beneficios serían más evidentes.

Although reducing the number of maternal deaths is one of the Millennium Development Goals, these deaths constitute merely the tip of the iceberg of severe morbidity related to pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium. The extent of all this morbidity is still unknown, but must be confronted before any real improvement in maternal health can in fact take place. The incidence of acute complications during pregnancy may possibly be similar in both developed and developing countries; nevertheless, the differences in how these complications are detected and managed may be responsible for the enormous gap in maternal mortality ratios and in the incidence of long-term sequelae.Citation1

Since the 1990s, a special group of women who have survived acute and severe complications of pregnancy and who escaped death by luck or by receiving timely, appropriate care, have attracted the attention of investigators and policy-makers. Their experience is known as a “near-miss”.Citation2 These women share important characteristics with those who die during pregnancy, childbirth or the puerperium, and constitute a proxy model for maternal death. Moreover, studying what happened to them is made easier by their greater numbers and the possibility of being able to listen to them directly.Citation3–5

Although the concept of near-miss is already well-established, a consensual definition has yet to be adopted, including how the women comprising this group may be recognised.Citation6–8 Considering the potential of near-misses to contribute to the development of strategies for reducing maternal mortality, we decided to study different aspects of them using different approaches.

This paper summarises a series of studies on maternal morbidity carried out by our research group at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, School of Medical Sciences, Universidade Estadual de Campinas (UNICAMP) in Campinas, Brazil, and discusses their findings and significance. Over the last 20 years, our group has been working in the field of maternal mortality and more recently maternal near-misses almost entirely with local resources. There is an unfortunate negative belief as regards most research that, after a study has been performed, practically nothing will actually change in the setting where it was carried out. This is exactly what we do not want to happen with our data. We took up the challenge of writing a more conceptual paper outlining our experience, in order to share with other research groups from the developing world what can be done locally with limited resources. The paper covers the definition of a near-miss, the scoring system we developed for severe maternal morbidity, population-based studies and surveys that we undertook, information systems we set up in health and monitoring, and what we have learned from listening to women’s experiences. The papers reporting this research have been or are in process of being published elsewhere and are referenced in this paper.

Definitions

Following a long history of concern about and research on the subject of maternal mortality in Brazil, we recently began to intensify our interest in near-misses by carrying out a systematic literature review of the published data on the incidence of near-misses and the different operational definitions of them adopted in the studies.Citation9 We found that the majority (57%) of studies on the subject had adopted definitions related to the complexity of management of the cases (i.e. admission to intensive care units, need for hysterectomy or transfusions of blood derivatives), while 24% defined them according to the presence of certain clinical conditions (i.e. severe pre-eclampsia or uterine rupture), 15% according to the presence of organ failure (i.e. respiratory or renal failure, coma or shock) and 3% were based on a mixture of criteria (i.e. severe maternal morbidity score). In the studies reviewed, the near-miss ratio reported varied from 0.3/1,000 to 101.7/1,000 deliveries and the case-fatality ratio varied from 2:1 to 223:1. The review also found a tendency towards a greater in-hospital incidence of cases of near-miss in the studies in developing countries than in developed countries.Citation9

Evaluating the definitions and the scoring system for severe maternal morbidity

Our institution is a tertiary referral centre in the city of Campinas, São Paulo state, one of the most developed regions of Brazil. Approximately 3,000 deliveries are carried out annually there. Although a good part of the cases attended here are considered high risk, the occurrence of maternal death in this centre is infrequent. If we were to use only cases of maternal death for auditing the quality of obstetric care, it would probably be a fairly ineffective approach because of the low rate of maternal death. Likewise, services that deal with few obstetric cases or less complex cases find it difficult to use only cases of maternal death to evaluate the quality of obstetric care offered and the difficulties faced by women in obtaining maternity care. A long period of time would be required to accumulate a reasonable number of cases and by then it would be too late for a good number of women. Hence, we felt it was valuable to study cases of severe maternal morbidity and near-misses, to see what they would teach us about dealing with obstetric complications.

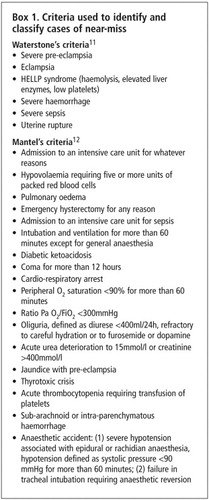

To evaluate the applicability of the different concepts of severe maternal morbidity and obstetric near-miss in hospitals, we surveyed cases of severe maternal morbidity in our hospital over a one-year period.Citation10 For this, different sets of criteria were used, as shown in Box 1.Citation11Citation12 These are not, of course, the only criteria used for identifying cases of severe maternal morbidity, but perhaps they are the most comprehensive ones. They allowed us to make additional assessments of other criteria for a near-miss in this population (including admission to an intensive care unit, organ dysfunction and the scoring of severe maternal morbidity).

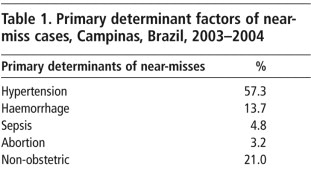

During the study period, all the women hospitalised in the obstetric wards, obstetric centre or in the intensive care unit were evaluated for the presence of criteria indicative of severe maternal morbidity. During this period, two maternal deaths occurred and 124 cases of severe maternal morbidity were identified. Mantel’s criteriaCitation12 yielded 112 cases of near-miss while Waterstone’s criteriaCitation11 yielded 90 cases, with an overlapping of both definitions in 78 cases. A total of 112 women were admitted to the intensive care unit, 35 for intensive support and 77 for monitoring and surveillance. A total of 45 women developed organ dysfunction. The principal causes of severe maternal morbidity found are shown in Table 1. They consisted predominantly of hypertensive syndromes, which are also the most common conditions found in cases of maternal deaths in this region. In this group of women, the use of diagnostic or therapeutic interventions not habitually carried out in low-risk obstetric care was evaluated (referred to here as “special procedures”). A total of 126 of these interventions were carried out, the most frequent being central venous access, echocardiography and mechanical ventilation. The mean period of hospitalisation was 10.3 (± 13.24) days. With respect to surveillance of severe maternal morbidity, we found that a two-tiered strategy of surveillance (screening and confirmation) would be more consistent and possibly more effective.Citation10

As a result of these findings, we tested the application of the severe maternal morbidity scoring system in this same group of women. The severe maternal morbidity scoring system is based on the existence of a continuum of morbidity, with normal pregnancy at one end, passing through the occurrence of a complication and different degrees of severity with maternal death at the other end.Citation13 Initially, we sought to identify the greatest possible number of cases of severe maternal morbidity by using a wide range of criteria. Next, a specific scoring system was applied in each case, depending on the presence or absence of factors of severity (organ failure, admission to intensive care, transfusion of more than three blood derivatives, prolonged intubation and major surgical interventions other than caesarean section). This system permits identification of the most severe cases, and once the score is applied to the survivors of severe maternal morbidity, it is possible to identify cases of near-miss.

According to the scoring system as applied to our sample, 20 cases were classified as near-miss and 104 cases as other severe maternal morbidity. Considering duration of hospitalisation and the use of special procedures, we observed that the group of near-miss women required more complex care over a longer period of time compared to women in the group of other severe morbidities (p<0.05). The mean number of special procedures carried out in the group of women with near-misses was 3.75 (±2.34) per case, whereas in the group of other severe morbidities, the number was 0.38 (±0.83). The mean duration of hospitalisation in near-miss cases was 24.2 days (±28.1), whereas in the group of other severe morbidities, this period was 7.6 days (±4.3). Among the cases of near-miss, there was a predominance of cases of haemorrhage, while in cases of other severe morbidities, hypertensive complications predominated. This institutional data does not necessarily reflect the national figures on maternal morbidity and mortality. We could hypothesise that hypertensive complications are more prevalent and heterogeneous in terms of severity and that they are more effectively managed in a tertiary facility. The implications for practice of haemorrhage being the main determinant cause of a near-miss, taking into account that it is generally identified as having the most complex complications, are that it demands the prompt availability of surgical, anaesthetic and haemotherapeutic procedures. This study provided additional validation of the severe maternal morbidity scoring system, and we concluded that the same scoring system could be used to objectively describe and identify the most extreme cases of severe maternal morbidity (near-misses).Citation14Citation15

The use of different sets of criteria for identifying cases of severe maternal morbidity and/or near-misses worldwide is a problem that still needs to be resolved, especially for purposes of comparing data. It was not our intention to set unique criteria, but rather to show our experience in testing different criteria in the field. A common definition and standard procedures for the identification of severe maternal morbidity and near-miss cases should probably be addressed in the near future. The World Health Organization and other international health agencies could play a major role in this challenge.

Population-based study of severe maternal morbidity

After investigating the concept of severe maternal morbidity and near-miss in a hospital environment, we carried out a population-based study of the occurrence of severe maternal morbidity and maternal and perinatal mortality in the city of Campinas. Hospital coverage for obstetric cases in the region is almost 100%, with only 0.4% of home deliveries being reported in 1996.Citation16 The few cases of deliveries taking place outside the hospital are due to the current trend of home delivery among women with a high socio-economic status and to deliveries occurring on the way to hospital. In both cases, maternal and perinatal complication rates are not very likely to be significant.Footnote*

The cases of interest were identified by prospective surveillance carried out in all the maternity hospitals (public and private) in the city over a three-month period. The objective was to identify all the cases of maternal and perinatal death and severe maternal morbidity. The cases of maternal morbidity were identified in accordance with a set of criteria similar to that used in the hospital-based study. All the cases identified were submitted to clinical audit by the municipal and regional Maternal Mortality Committees.Citation17

A total of 158 adverse perinatal events were identified. In this period, 4,491 liveborn infants were delivered and there were 32 fetal deaths, or 34.9 fetal deaths per 1,000 deliveries. Four maternal deaths (maternal mortality ratio 89 per 100,000 live births) and 95 cases of severe maternal morbidity (21.2 per 1,000 live births) occurred. The case-fatality ratio was 24:1. Hypertensive complications were responsible for 57.8% of cases of severe maternal morbidity, followed in frequency by cases of post-partum haemorrhage. The audit process revealed that provision of appropriate care was delayed in 54 cases (34%). Of these 54 cases, in 32 (59%), the delay occurred in initiating adequate treatment despite the fact that the woman had already reached a health care service; in 23 cases (43%), the delay occurred in seeking care; and in only 7 cases (13%) was the delay caused by difficulty in obtaining access to health services.Citation17 The majority of delays, then, were due to a physician’s decisions as regards both time and appropriateness of care. During the audit process specifically for the cases of severe maternal morbidity, it was found that the delays were mainly due to lack of timely use of magnesium sulphate for pre-eclampsia, management of pre-eclampsia and hypertension, adherence to antenatal care guidelines, management of obstetric haemorrhage or use of prophylaxis for post-partum haemorrhage. We recommended that these topics become a priority part of the content of refresher courses for professionals and also that the institutions involved should check whether any constraints existed that were causing delays in or failure to implement best practice.Citation17

It is important to note that in this proxy population-based prospective study, the causes of severe maternal morbidity were very similar to those obtained in the previously described institutional study.Citation10 This is relevant as it indicates that it is possible to identify interventions that could be carried out during antenatal careCitation19Citation20 or deliveryCitation20 to try to reduce the risk of maternal death from specific, identified problems.

The main conclusions of this study were that, despite the large number of cases, investigation of the cases of severe maternal morbidity was feasible. Moreover, the process of auditing these cases led to increased experience in a wide spectrum of causes of maternal morbidity, which also motivated the members of the Maternal Mortality Committees to tackle determinants of maternal death. Hypertensive complications and post-partum haemorrhage were highlighted as priority topics for training. Concrete recommendations for changing the practice of physicians in order to address these issues were to use audit and feedback on proper evidence based interventions, the opinions of local leaders on when and how to implement such evidence based interventions and the use of reminders of best practices.Citation21

Information systems in health and monitoring of severe maternal morbidity

In several countries, much of the information on health is routinely collected by governmental and/or non-governmental organisations. The use of information on health stored in public information systems may be useful for the continuous and prospective monitoring of severe maternal morbidity. If these systems operated automatically and concurrently with the care provided (using, for example, the hospital cost management systems) a mechanism of local or in-hospital alert could be established so that a differentiated support system would trigger therapeutic or preventive interventions, in each case automatically indicated by the system.Citation22

In the case of maternal morbidity, the development of such a system and mechanisms of alert constitute an innovation designed to stop the progression of a woman through the continuum of severe morbidity and to prevent a maternal death. However, very few countries systematically use this approach.Citation23Citation24 In Brazil, one of the principal public sources of information on health is the Ministry of Health. In this context, we carried out a studyCitation25 with the aim of identifying the medical records of those women with conditions suggestive of severe maternal morbidity, using the Brazilian Hospital Information System (HIS). The criteria shown in Box 1 have been adapted to permit recognition of the records stored in the Hospital Information System. In addition to identifying the records, we also attempted to describe the diagnoses and the procedures used, with the aim of identifying factors associated with maternal death. The records of women hospitalised during pregnancy, delivery or in the puerperium in the 27 Brazilian state capitals in 2002 were analysed. The records of the women who had at least one of the criteria that we had adopted as defining severe maternal morbidity were selected. The records of 32,379 women with at least one factor suggestive of severe maternal morbidity were identified, as well as 154 maternal deaths (case-fatality ratio 210:1). The consolidated ratio of severe maternal morbidity observed was 44.3/1,000 liveborn infants. Despite several limitations, principally the need for a structured information system, the perspective of routinely using the information collected was found to be promisingCitation25 for setting up an automatic mechanism of alert. However, implementation of this mechanism first requires the development of agile local information systems to make it viable.

Estimating maternal morbidity by population surveys

Population surveys and demographic and health surveys may constitute good sources of information on maternal morbidity, particularly in places where integrated systems of epidemiological information have not yet been implemented.Citation18Citation26 We analysed the information obtained from demographic and health surveys carried out in Latin America and the Caribbean on maternal morbidity. The databases of seven population surveys carried out in the 1990s in Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Nicaragua and Peru contained indirect information on maternal morbidity identified through complications reported as associated with childbirth. The rate of complications reported by the women surveyed was very high, 20–40% of all deliveries in the majority of the countries. We concluded that the majority of these demographic and health surveys involving questions on maternal morbidity resulted in over-estimation of the occurrence of morbidity, possibly because they were not adequately validated.Citation27

Using this same approach, we recently evaluated the situation in Brazil by geographical region from data in a 1996 demographic and health survey. This showed a varied panorama of reported complications, ranging from around 15% in the state of São Paulo to as high as 23% in the northern part of the country. These variations were in line with the degree of economic and human development of the different regions of the country, with complications being significantly greater in the east central, northeast, north and west central parts of the country, the least developed areas of Brazil.Citation28 This finding has stimulated our decision to continue investigating the regional distribution of occurrences of severe maternal morbidity, probably through a process of geographical referencing, taking into consideration the geographic location of the occurrences and the local demographic characteristics, as well as the characteristics of the quantity and quality of maternal health services available. This currently represents a challenge to both scientists and health planners, if measures specifically aimed at combating local and regional difficulties are to be recommended and implemented with the clear objective of avoiding delays and improving maternal health.

To further evaluate the question of the validity of questionnaires on morbidity, we carried out a systematic review on the subject. This was our first attempt to summarise the findings of various studies on the validation of questionnaires on severe maternal morbidity in developing countries. We found that information on the occurrence of eclampsia and other hypertensive complications in the same seven surveys from Latin American and the Caribbean mentioned earlier was considered satisfactorily accurate in four out of seven studies, dystocia and infection in only two, and the questions dealing with haemorrhagic complications were considered satisfactory in only one. Another finding of this review was that, when the true prevalence of the condition investigated is low (<5%), studies frequently over-estimate prevalence.Citation29

We therefore suggest that questionnaires on severe maternal morbidity included in demographic and health surveys should be previously validated and, if necessary, correction factors developed to adjust for the estimates obtained.Citation29 In view of these findings, we developed a questionnaire for the evaluation of the occurrence of severe maternal morbidity in Portuguese. This questionnaire is currently being validated and the correction factors obtained may be used to interpret future population surveys that adopt this instrument.

Listening to women’s experience

One of the principal advantages of case studies of near-misses is the possibility of hearing the experience of the women directly. Women who have survived potentially fatal complications in pregnancy or the puerperium are believed to be able to adequately report the obstacles and delays they had to face to assure their survival.Citation30 Considering these points, we designed a qualitative research study to acquire knowledge on the experience of women who have survived acute and severe complications during pregnancy and the puerperium. Our preliminary findings show that there were difficulties and obstacles that the women had to overcome to receive adequate care when the complication developed, including problems related to the quality of primary level care, lack of local resources, poverty and correspondent social disadvantages, and delays in the referral process. This study is still in process, but its findings will provide important insights into the causes of maternal morbidity in our region. Transferring knowledge coming from research into practice is a difficult task, especially in developing country settings. However, the lessons already learnt from women indicate the need for improvement of local primary level care in identifying and referring complications during pregnancy so that they can be adequately and comprehensively managed in time.

Discussion

No consensus has yet been reached on how best to recognise cases of severe maternal morbidity and obstetric near-miss. Although lack of standardisation in the definition and evaluation methods represents an aspect that still requires improvement, since this deficiency hampers comparison between services and over time, the diversity of applications of the concept represents its versatility. As described in the previous sections, the definition of morbidity or near-miss may be tailored to each purpose or to each population of interest, and this facilitates its use at the different levels for action and planning.

For a long time, reducing the number of complications occurring during pregnancy was the principal objective of many programmes aimed at reducing maternal mortality.Citation31 Nevertheless, the majority of acute, severe obstetric complications are considered difficult to predict and seldom possible to prevent, which may explain, in part, the failure of a good number of these programmes.Citation32 On the other hand, appropriate treatment for the majority of these complications is known and timely treatment may avoid the occurrence of a great number of maternal deaths.Citation1 In this context, the study of severe maternal morbidity and cases of near-miss may contribute towards improving strategies for combating acute complications of pregnancy, thus contributing towards reducing the number of deaths. However, probably the main reason why more progress in reducing maternal mortality has not been made is not the lack of knowledge of what the complications are or what to do about them, but rather the organisation, delivery and utilisation of services. This appears to include significant regional differences, as found in Brazil. For this reason, research on these factors should be repeated, whenever possible, in different contexts to determine the local characteristics upon which the adoption of appropriate interventions depends. In fact, up to the present moment, no large population-based studies that deal directly with severe maternal morbidity (near-miss) have been carried out. In our view, this justifies performing a large, prospective, international, multicentre study, preferably in developing countries in which maternal mortality is high, to learn more about the condition and the factors associated with it.

A system of epidemiological surveillance based on the early identification of cases of severe maternal morbidity would permit a more adequate level of monitoring and care, stopping the progression of women through the continuum of morbidity and preventing the occurrence of avoidable deaths.Citation4 On the other hand, carrying out audits of the care provided in cases of severe maternal morbidity may permit a local diagnosis of the causes of delay either in seeking, gaining access to or receiving adequate care. This type of audit is being used more and more frequently as a complement to the reviews of maternal death and may help support the planning of actions adapted for each situation identified.Citation33

Conclusions

The study of severe maternal morbidity may contribute significantly to the formulation of strategies to reduce maternal mortality. The versatility of the concept, together with the greater frequency of cases and the possibility of directly interviewing the survivors of severe complications, allows local actions to be implemented within a global perspective to improve maternal health. Recommendations for changing practice would be the implementation of multi-faceted strategies based on audit and feedback.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge all the people in our institution who have participated in all stages of our research on maternal mortality and morbidity, including sponsors, researchers, interviewers, statisticians, physicians, social workers, research assistants and the women who agreed to share their experiences. Special recognition goes to Anibal Faúndes, who motivated our interest in this subject and its potential for improving women’s health in our country.

Notes

* There might be some concern about the use of multiple hospital-based studies as a proxy for a population-based study because, according to Fortney and Smith,Citation18 they include only women who sought treatment. However, in the specific situation of Campinas, the “untreated” segment of the target population was considered to be irrelevant.

References

- A Paxton, D Maine, L Freedman. The evidence for emergency obstetric care. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 88(2): 2005; 181–193.

- W Stones, W Lim, F Al-Azzawi. An investigation of maternal morbidity with identification of life-threatening “near miss” episodes. Health Trends. 23(1): 1991; 13–15.

- CJ Berg, FC Bruce, WM Callaghan. From mortality to morbidity: the challenge of the twenty-first century. Journal of American Medical Women’s Association. 57(3): 2002; 173–174.

- RC Pattinson, M Hall. Near misses: a useful adjunct to maternal death enquiries. British Medical Bulletin. 67: 2003; 231–243.

- V Filippi, R Brugha, E Browne. Obstetric audit in resource-poor settings: lessons from a multi-country project auditing “near miss” obstetrical emergencies. Health Policy and Planning. 19(1): 2004; 57–66.

- V Filippi, E Alihonou, S Mukantaganda. Near misses: maternal morbidity and mortality. Lancet. 351(9096): 1998; 145–146.

- SA Nashef. What is a near miss?. Lancet. 361(9352): 2003; 180–181.

- L Say, RC Pattinson, AM Gulmezoglu. WHO systematic review of maternal morbidity and mortality: the prevalence of severe acute maternal morbidity (near miss). Reproductive Health. 1(1): 2004; 3.

- JP Souza, JG Cecatti, MA Parpinelli. [Systematic review of near miss maternal morbidity]. [In Portuguese]Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 22(2): 2006; 255–264.

- JP Souza, JG Cecatti, MA Parpinelli. Appropriate criteria for identification of near-miss maternal morbidity in tertiary care facilities: a cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth. 2007(In press)

- M Waterstone, S Bewley, C Wolfe. Incidence and predictors of severe obstetric morbidity: case-control study. BMJ. 322(7294): 2001; 1089–1094.

- GD Mantel, E Buchmann, H Rees. Severe acute maternal morbidity: a pilot study of a definition for a near-miss. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 105(9): 1998; 985–990.

- SE Geller, D Rosenberg, S Cox. A scoring system identified near-miss maternal morbidity during pregnancy. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 57(7): 2004; 716–720.

- JP Souza, JG Cecatti. The near-miss maternal morbidity scoring system was tested in a clinical setting in Brazil. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 58(9): 2005; 962.

- JP Souza, JG Cecatti, MA Parpinelli. [Factors associated with the severity of maternal morbidity for the characterization of near miss]. [In Portuguese]Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia. 27(4): 2005; 197–203.

- Brazil. [National Demographic Health Survey 1996]. [In Portuguese] ORC Macro: Measure DHS STAT compiler, 2006. At: <www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pub_details.cfm?ID=119&ctry_id=49&SrchTp=available>. Accessed 13 August 2007

- E Amaral, JP Souza, FG Surita. A population-based surveillance study on severe maternal morbidity (near-miss) in Campinas, Brazil: The Vigimoma Project. XVIII FIGO World Congress of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Kuala Lumpur. 2006 Abstract 2:96

- JA Fortney, JB Smith. Measuring maternal morbidity. M Berer, TKS Ravindran. Safe Motherhood Initiatives: Critical Issues. 2000; Reproductive Health Matters: London, 43–50.

- G Carroli, C Rooney, J Villar. How effective is antenatal care in preventing maternal mortality and serious morbidity? An overview of the evidence. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 15(Suppl.1): 2001; 1–42.

- OM Campbell, WJ Graham. Lancet Maternal Survival Series steering group. Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: getting on with what works. Lancet. 368(9546): 2006; 1284–1299.

- N Chaillet, E Dubé, M Dugas. Evidence-based strategies for implementing guidelines in obstetrics: a systematic review. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 108(5): 2006; 1234–1245.

- MH Sousa, JG Cecatti, EE Hardy. [Health information systems and surveillance of severe maternal morbidity and maternal mortality]. [In Portuguese]Revista Brasileira de Saúde Materno Infantil. 6(2): 2006; 161–168.

- Canada, Minister of Public Works and Government Services. Health Canada: special report on maternal mortality and severe morbidity in Canada - enhanced surveillance: the path to prevention. Ottawa, 2004.

- US Agency for International Development. Developing and implementing a hospital-based surveillance system for maternal and newborn health. At: <www.mnh.jhpiego.org/global/dvlsrvsys.asp>. Accessed 15 May 2005

- MH Sousa, JG Cecatti, EE Hardy. Use of the health information systems on severe maternal morbidity (near miss) and maternal mortality. At: <http://libdigi.unicamp.br/document/?code=vtls000386164>. Accessed 13 August 2007

- MK Stewart, CK Stanton, M Festin. Issues in measuring maternal morbidity: lessons from the Philippines Safe Motherhood Survey Project. Studies in Family Planning. 27(1): 1996; 29–35.

- JP Souza, MA Parpinelli, E Amaral. Obstetric care and severe pregnancy complications in Latin America and Caribbean: an analysis of information from demographic and health surveys. Pan American Journal of Public Health. 21(6): 2007; 396–401.

- Souza JP, Sousa MH, Parpinelli MA, et al. Self-reported maternal morbidity and associated factors among Brazilian women. (Submitted 2007).

- JP Souza, MA Parpinelli, E Amaral. Population surveys using validated questionnaires provided useful information on the prevalence of maternal morbidities. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2007(In press)

- A Weeks, T Lavender, E Nazziwa. Personal accounts of “near-miss” maternal mortalities in Kampala, Uganda. BJOG. 112(9): 2005; 1302–1307.

- Australia. Queensland Council on Obstetric and Paediatric Morbidity and Mortality. Mater Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, Mater Hospitals Maternal and Perinatal Audit. Guidelines for Queensland hospitals. Brisbane, 2001.

- A Rosenfield, D Maine, L Freedman. Meeting MDG-5: an impossible dream?. Lancet. 368(9542): 2006; 1133–1135.

- G Penney, V Brace. Near miss audit in obstetrics. Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 19(2): 2007; 145–150.