Abstract

Maternal mortality continues to be the major cause of death among women of reproductive age in many countries. Data from published studies and Demographic and Health Surveys show that gains in reducing maternal mortality between 1990 and 2005 have been modest overall. In 2005, there were about 536,000 maternal deaths, and the maternal mortality ratio was estimated at 400 per 100,000 live births, compared to 430 in 1990. Noteworthy declines took place in east Asia (4% per year) and north Africa (3% per year). Maternal deaths and mortality ratios were highest in sub-Saharan Africa and southeast Asia and low in east Asia and Latin America/Caribbean. In 11 of 53 countries with data, fewer than 25% of women had had at least four antenatal visits. About 63% of births were attended by a skilled attendant: from 47% in Africa to 88% in Latin America/Caribbean. In 16 of 23 countries with data, less than 50% of the recommended levels of emergency obstetric care had been fulfilled. Only 61% of women who delivered in a health facility in 30 developing countries received post-partum care, and far fewer who gave birth at home. Countries with maternal mortality ratios of 750+ per 100,000 live births shared problems of high fertility and unplanned pregnancies, poor health infrastructure with limited resources and low availability of health personnel. The task ahead is enormous.

Résumé

Dans beaucoup de pays, la mortalité maternelle demeure la principale cause de mortalité chez les femmes en âge de procréer. Les données d’études et des enquêtes démographiques et sanitaires montrent de modestes progrès dans la réduction de la mortalité maternelle entre 1990 et 2005. En 2005, on dénombrait 536 000 décès maternels, et le taux de mortalité maternelle était estimé à 400 pour 100 000 naissances vivantes, contre 430 en 1990. Des diminutions sensibles ont eu lieu en Asie de l’Est (4% par an) et en Afrique du Nord (3% par an). Le taux de mortalité et les décès maternels étaient les plus élevés en Afrique subsaharienne et en Asie du sud-est, faibles en Asie de l’est et Amérique latine/Caraïbes. Dans 11 des 53 pays possédant des données, moins de 25% des femmes avaient eu au moins quatre visites prénatales. En 2007, près de 63% des accouchements étaient assistés par du personnel qualifié : de 47% en Afrique à 88% en Amérique latine/Caraïbes. Dans 16 des 23 pays publiant des chiffres, moins de 50% des niveaux recommandés de soins obstétricaux d’urgence étaient atteints. Dans 30 pays en développement, seulement 61% des femmes ayant accouché dans un centre de santé avaient reçu des soins post-partum ; ce chiffre diminuait encore pour les naissances à la maison. Les pays avec un taux de mortalité maternelle supérieur à 1000 pour 100 000 naissances vivantes avaient en commun une fécondité élevée et de nombreuses grossesses non planifiées, des infrastructures sanitaires médiocres avec des ressources limitées et un personnel de santé insuffisant. La tâche à accomplir est immense.

Resumen

En muchos países, la mortalidad materna continúa siendo la principal causa de muerte de mujeres en edad reproductiva. Los datos de estudios publicados y Encuestas Demográficas y de Salud muestran que los logros en la disminución de mortalidad materna entre 1990 y 2005 han sido moderados. En 2005, murieron aproximadamente 536,000 mujeres, y la razón de mortalidad materna se calculó a 400 por cada 100,000 nacidos vivos, comparada con 430 en 1990. Se lograron importantes descensos en Asia oriental (4% al año) y Ãfrica septentrional (3% al año). Ãfrica subsahariana y Asia del sudeste experimentaron las muertes maternas y razones de mortalidad más altas; Asia oriental y Latinoamérica y el Caribe, las más bajas. En 11 de 53 países con datos, menos del 25% de las mujeres habían asistido a por lo menos cuatro consultas antenatales. Un 63% de los partos recibieron asistencia calificada: del 47% en Ãfrica al 88% en Latinoamérica y el Caribe. En 16 de 23 países con datos, se había alcanzado menos del 50% de los niveles recomendados de cuidados obstétricos de emergencia. Sólo el 61% de las mujeres que dieron a luz en establecimientos de salud en 30 países en desarrollo recibieron atención posparto, y mucho menor fue el porcentaje de las que dieron a luz en su hogar. Los países con razones de mortalidad materna de 750+ por cada 100,000 nacidos vivos compartían problemas de alta fertilidad y embarazos no planeados, una infraestructura de salud deficiente con recursos limitados y poca disponibilidad de personal de salud. La tarea pendiente es enorme.

A maternal death is defined as “the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management but not from accidental or incidental causes”. The causes of maternal deaths may be either direct – such as obstetric complications of pregnancy, delivery and the puerperium – or indirect – such as pre-existing diseases or diseases developed during the pregnancy that are worsened by the pregnancy. A pregnancy-related death is defined as “the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the cause of death”.Citation1 The 10th International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) noted that modern life-sustaining procedures can delay death. Therefore, a new category of late maternal death was introduced, defined “as the death of a woman from direct or indirect obstetric causes more than 42 days but less than one year after termination of pregnancy”. The definition of maternal death cannot be applied when the precise cause of death is not known. Therefore, maternal deaths are generally under-reported, even in countries with relatively good vital registration systems and record-keeping. Deaths in early pregnancy are especially more likely to be missed.

Maternal mortality ratio (MMR), defined as the number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, is the most commonly used measure to illustrate maternal mortality. It is also one of the measures used to monitor progress towards the achievement of the goal of improving maternal health in Millennium Development Goal 5 (MDG 5). Alternative measures include the maternal mortality rate – the number of maternal deaths per 1,000 women of reproductive age. The adult lifetime risk of maternal death takes into account both the probability of becoming pregnant and the probability of dying as a result of that pregnancy, cumulated across a woman’s reproductive years.

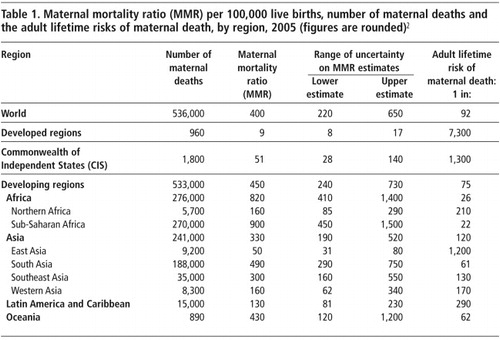

Maternal mortality continues to be the major cause of death among women of reproductive age in many countries. The most recent estimates show that in 2005, around 536,000 women died of complications of pregnancy, childbearing or unsafe abortion (Table 1>).Citation2 The MMR was estimated at 400 per 100,000 live births and a lifetime risk of one maternal death in 92. Maternal deaths were unevenly distributed across the world’s regions and were not in proportion to the populations of women of reproductive age in those regions. Nearly half of all maternal deaths (270,000) occurred in sub-Saharan Africa, where only 10% of all women of reproductive age (15 to 49 years) in the world resided in 2005. South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa together accounted for 458,000 (that is, 86%) of maternal deaths globally, though they accounted for 22% of all women of reproductive age in 2005. The MMR is 900 per 100,000 live births in sub-Saharan Africa and the probability that a 15-year old female will eventually die from maternal causes (adult lifetime risk of maternal death) is also the highest, 1 in 22. Comparing these with the MMR of 9 and the lifetime risk of maternal death of 1 in 7,300 for the developed regions indicates that a pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa is 100 times more likely to take the life of a woman than a pregnancy in a developed country (900/9=100). The cumulated lifetime risk of maternal death is 332 times higher for a woman in sub-Saharan Africa compared to a woman in the developed regions (7300/22=332). Perhaps there is no other health indicator that shows such a high degree of inequity across the world’s regions.

Global trends in maternal mortality

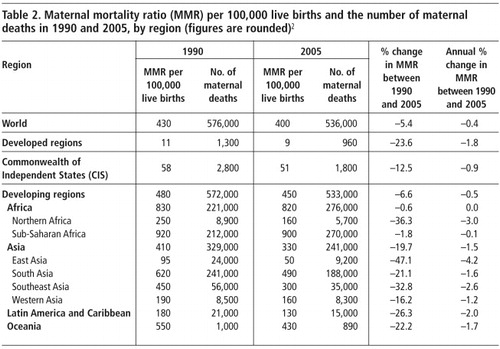

The often-raised question of whether maternal mortality has declined over time has been difficult to address because of changes in the method of estimation and the availability of data for different updates on internationally comparable estimates of maternal mortality made by WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA. In addition, the wide uncertainty margins of the estimates have made the comparisons difficult. The 2005 update of global maternal mortality estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and the World BankCitation2 has addressed this question by applying the same methodology to the information for 1990 and 2005 (Table 2). Overall, the progress in reducing maternal mortality has been modest – a decline of 5.4% between 1990 and 2005, or 0.4% per year during this period (Table 2). The regions with noteworthy declines in maternal mortality were eastern Asia (4% per year) and northern Africa (3% per year). Little progress was made in the two regions with relatively high MMR and the number of maternal deaths, namely sub-Saharan Africa, western Asia and south Asia, where the annual change amounted to 0.1%, 1.2% and 1.6%, respectively, between 1990 and 2005. It is estimated that for MDG 5 to be achieved by 2015, an annual change of 5.5% is needed,Citation2 yet neither globally nor regionally is this level being met. However, the MMR in a number of countries, including Bangladesh, China, Malaysia, Thailand and Sri Lanka, has been halved over a relatively short period.Citation3

Because of huge variation across countries in sources of data, type and completeness of information available and extent of missing information, the estimates for 2005Citation2 used an approach that is based on reconciliation of data from different sources. In 65 countries, maternal mortality data were derived from vital registration – with good or poor and uncertain attribution of cause of death; in 28 countries from the direct sisterhood methods used in Demographic and Health Surveys of households; in 4 countries from reproductive age mortality studies (RAMOS) and in 13 countries from disease surveillance, sample registration, censuses or special studies. For the remaining 61 countries with no national data on maternal mortality, estimates were predicted using a statistical model. Estimates were adjusted for under-reporting when necessary.Citation2 Although this methodology for MMRs was considered most feasible, the wide margin of uncertainty associated both with variability of data sources and the prediction model restricts the ability to compare MMRs across groups of countries with differing estimation strategies.

Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) provide an alternative source of data on maternal mortality as well as on other health and population indicators, and are particularly valuable in settings where the vital registration system is poor and where many deaths occur outside the health system. In these surveys, maternal death is defined as any death that occurs during pregnancy, childbirth or the two months following a birth or termination of the pregnancy and estimates the MMR from the survivorship of sisters of survey respondents (known as the “sisterhood method”). This information is elicited from survey respondents in a set of questions on the survivorship of all live-born children of the respondent’s biological mother. These data allow deaths and births to be placed in calendar time, permitting the calculation of sex-and age-specific death rates for a defined reference period. The MMR estimated using DHS data typically refer to a period about seven years prior to the survey. Thus, most of the data analysed in this paper refer to the year 2000 or earlier. DHS data also have other limitations. Estimates are based on women’s reports, which are subject to recall error, including misreporting and under-reporting. It has been shown that the sisterhood method underestimates the actual level of maternal mortality.Citation4Citation5 Large sample sizes are needed for estimating maternal mortality in this way and the confidence intervals of the estimates are relatively wide. However, the data allow comparisons across countries because of the standard instruments and design.

More than 500 women were dying per 100,000 live births in 22 of the 42 developing countries for which MMRs are available from DHS data (Table 3).Citation6 The highest MMRs were in sub-Saharan Africa, where the MMR was over 500 per 100,000 live births in 19 of the 27 countries with DHS data. Chad now has the highest MMR of all 42 countries: 1,099 per 100,000 live births, while South Africa has the lowest ratio of 150 per 100,000 live births in the sub-Saharan African region. Maternal mortality ratios were generally low in Latin America and the Caribbean, except in Haiti where the ratio was 523 per 100,000 live births. The lowest MMR was found in Jordan (35 per 100,000 live births).

Antenatal care

Antenatal care is an important component of maternal health and covers a range of activities, including nutrition education, tetanus vaccine, malaria, HIV information, immunisation and services for monitoring of potential complications. The set of antenatal care interventions can contribute directly or indirectly to reducing maternal deaths. WHO recommends at least four antenatal care visits with trained health personnel (doctor, nurse or midwife) during normal pregnancy.

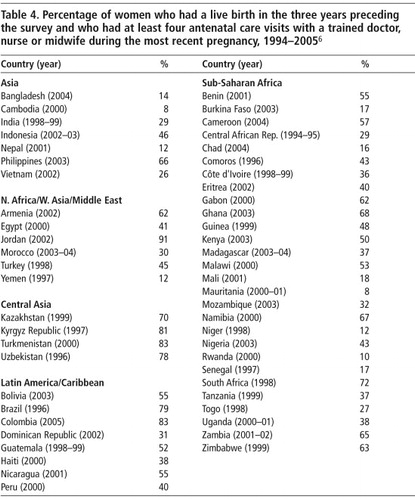

In 11 of 53 countries with DHS data on antenatal care visits (Bangladesh, Cambodia, Nepal, Yemen, Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Rwanda and Senegal) fewer than 25% of women who had a live birth in the three years preceding the survey had had at least four antenatal visits with a trained doctor, nurse or midwife during their most recent pregnancy (Table 4). In general, there has been an increase over time in the percentage of women who had at least four antenatal care check-ups. However, in some countries, the percentage had declined. The most notable decline was found in Indonesia, from 66% in 1997 to 45% in 2002–2003.

Births delivered by skilled birth attendants

The percentage of births delivered by skilled health attendants is associated with MMR. MMRs were halved in some developed countries in the late 19th century due to the provision of professional midwifery care at birth.Citation3 Skilled attendance at birth is a key indicator for monitoring a country’s progress in achieving MDG 5. Global targets for the percentage of all deliveries attended by skilled health attendants are 80% by 2005, 85% by 2010 and 90% by 2015.

The term “skilled attendant” refers to “an accredited health professional – such as a midwife, doctor or nurse – who has been educated and trained to proficiency in the skills needed to manage normal (uncomplicated) pregnancies, childbirth and the immediate post-natal period, and in the identification, management and referral of complications in women and newborns”.Citation7 The presence of a skilled attendant is an essential but not always a sufficient condition for safe delivery. Also needed is access to referral facilities able to address obstetric complications.

An estimated 63% of all births were attended by skilled health personnel.Citation8 The figure was 99% in the developed regions as compared to 59% in developing countries. Considerable regional variation was observed: 47% in Africa, 61% in Asia, 80% in Oceania, 88% in Latin America and the Caribbean, and 99% in Europe and North America. Within each region, moreover, variations were found by sub-region and country. In all the sub-regions of Africa for example, the percentages of births attended by skilled personnel were lowest in East Africa (34%) and West Africa (40%). In Asia, it was lowest in south-central Asia (44%).

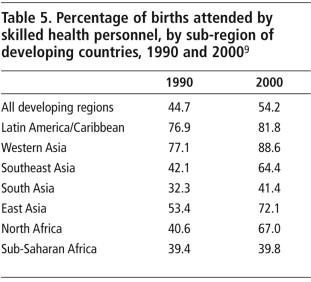

Sub-Saharan Africa is not only characterised by the lowest coverage of births attended by skilled health personnel, but also by the absence of any progress in this critical indicator over the decade 1990–2000. A recent study shows that progress in the percentage of births delivered by a skilled attendant was made in all developing sub-regions, most notably in east Asia, southeast Asia and northern Africa. In contrast, almost no progress was made in sub-Saharan Africa (Table 5), where the coverage was 39.4% in 1990 and 39.8% in 2000.Citation9

DHS data show that among women who reported deliveries in the three years prior to interview, the most recent birth of fewer than 25% of women in Bangladesh, Chad, Haiti, Mali, Mozambique, Nepal, Niger and Uganda was assisted by a trained doctor, nurse or midwife.Citation6 Skilled attendance at delivery was exceptionally low in Nepal (12%) and in Bangladesh and Chad (15% each). A general increase in the percentage of deliveries attended by skilled attendants was noticed where two surveys, generally five years apart, had been conducted. Skilled attendance at delivery was nearly universal (97–100%) in Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Over a period of roughly five years, the increase in skilled attendance at delivery was 23 percentage points in Morocco, 21 percentage points in Viet Nam, 19 percentage points in Namibia, 16 percentage points in Egypt and 9 percentage points in India. In Nepal and Bangladesh, where most deliveries continue to take place at home, the increase amounted to three percentage points over a five-year period. However, declines in the proportion of skilled attendance were witnessed in Indonesia, from 51% in 1997 to 43% in 2002–2003, in Mozambique from 41% in 1997 to 21% in 2003, and in Uganda from 35% in 1995 to 18% in 2000–01. The reasons for these declines need to be studied to reverse the trend.

Emergency obstetric care

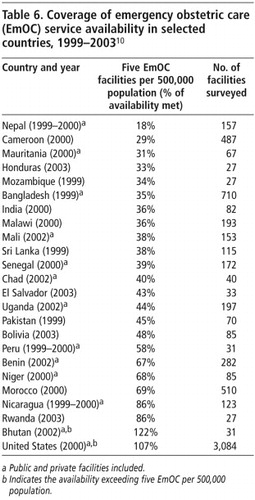

For the approximately 15% of women in every setting who experience complications of pregnancy and delivery and in the post-partum period, emergency obstetric care must be accessible to prevent maternal deaths. These facilities are often not available in resource-poor settings, which is the main reason why maternal mortality levels are high. Table 6 shows the extent to which recommended levels of emergency obstetric care were available for the size of population in the 23 developing countries where needs assessments were undertaken.Citation10 In 16 of the 23 countries, less than 50% of the recommended levels had been achieved.

Post-partum care

The majority of maternal deaths occur from the third trimester of pregnancy to the first week following delivery or abortion.Citation3 A recent report, based on DHS data, shows that only 61% of women who delivered in a health facility in 30 developing countries received post-partum care,Citation11 and where most births took place at home, the percentage receiving post-partum care tended to be much lower. For example, only 11% of women received post-partum care in Ethiopia, 27% in Bangladesh and 28% in Nepal. Even among those who did seek a post-partum check-up, most did so three or more days following delivery outside of health facilities. In fact, this check-up should be within 24 hours after delivery, and all women should receive it.

Reduced maternal death rates through contraceptive use

In general, there is an inverse relationship between levels of antenatal, delivery and post-partum coverage and maternal mortality ratio. However, some countries have experienced declines in maternal mortality ratios despite limited coverage and no apparent progress in these indicators. In Bangladesh, for example, although about 90% of deliveries continue to take place at home and are assisted by unskilled birth attendants or family members,Citation12 the maternal mortality ratio fell by 22% over 12 years, reaching 320 per 100,000 live births in 1998–2000. This progress may be attributed in part to the increase in contraceptive use over the period and the resulting decline in fertility and unplanned pregnancies. MMR shows the obstetric risk once a woman is pregnant, but increased use of contraception directly affects the maternal death rate per 1,000 women of reproductive age and the lifetime risk of maternal death, by reducing the number of pregnancies. It is estimated that in 2000, 90% of abortion-related and 20% of obstetric-related mortality and morbidity globally could have been averted by the use of effective contraception by women wishing to postpone or cease further childbearing.Citation13

In sub-Saharan Africa, the use of modern contraceptives continues to be low (20%) and fertility high (five children per woman) in the same countries with the highest maternal mortality. In this region, 24% of married women expressed an unmet need for contraception,Citation14 and nearly 30,000 women are dying each year due to unsafe abortion.Citation15

Profile of countries with high and low levels of maternal mortality

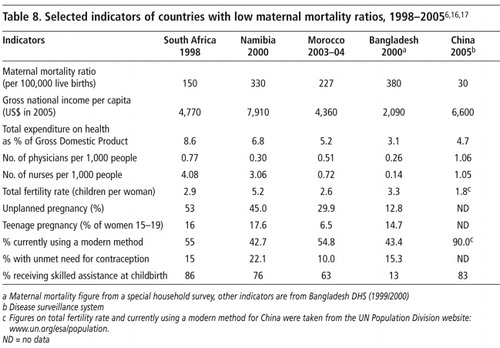

The five countries with maternal mortality ratios of 750 or higher per 100,000 live births for which there are recent DHS data (Chad, Congo, Guinea, Malawi, Rwanda) share several similar features – all are economically poor, are short of health personnel, have high levels of fertility and unplanned pregnancy (except in Chad and Guinea) and high levels of teenage pregnancy (except in Rwanda). Modern contraceptive prevalence is low, except in Malawi, which is high relative to the other four countries (Table 7). The number of recent deliveries assisted by a skilled attendant, however, ranged from 15% in Chad to 85% in Congo. A similar pattern of greater variability was observed for the indicator of at least four antenatal care visits among women who gave birth during three years prior to the survey.

Table 7. Citation16 Citation17

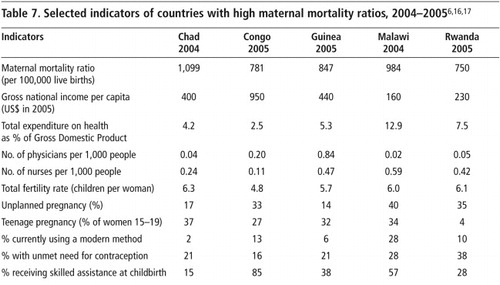

Developing countries with relatively low levels of maternal mortality (South Africa, Namibia, Morocco, Bangladesh, China) are more varied in terms of social, economic and reproductive health indicators (Table 8). However, except for Bangladesh they are economically better off and have better infrastructure, compared to countries with high MMRs. Likewise, their levels of fertility, teenage pregnancy and unplanned pregnancy are lower than in those with high MMRs. A notable exception is Namibia with 45% of pregnancies unplanned and 22% of women with unmet contraceptive needs.

Conclusions

Bangladesh, China, Egypt, Malaysia, Romania, Sri Lanka and Thailand have brought down maternal mortality in relatively short periods. These countries have used varying approaches and interventions. Ronsmans et alCitation3 identify the strategies used by each of these countries that contributed to the decline, including liberalisation of the abortion law in Romania, control of infectious diseases in Sri Lanka, increased contraceptive use in Bangladesh and expanding access to hospital care and midwifery care in Egypt, Honduras, Malaysia and Thailand.

The proportion of deliveries attended by skilled health personnel has increased in all regions except in sub-Saharan Africa yet the effect on maternal deaths has not been substantial. A study published recently using WHO data from 188 countries found that skilled attendance at delivery was not associated with significant reductions in maternal mortality until coverage rates of about 40% were reached, while four or more antenatal visits were not associated with significant reductions in maternal deaths until about 60% coverage was achieved.Citation18 In general, the gains in reducing maternal mortality have been modest and at present rates of progress will fall short of meeting the MDG 5 targets globally.Citation19 Efforts will need to be redoubled and multifaceted. This review of available data highlights the enormity of the task still ahead to reduce maternal mortality.

Note

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the World Health Organization.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the helpful comments and advice received from Elisabeth Åhman, Catherine d’Arcangues, Paul Van Look and especially Shireen Jejeebhoy.

References

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10th Revision. 1992; WHO: Geneva.

- World Health Organization, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank. Maternal mortality in 2005: estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, and World Bank. 2007; WHO: Geneva(In press)

- Cited in Ronsmans C, Graham WJ. Maternal mortality: who, when, where, and why. Lancet 2006;368(9542):1189–200.

- K Hill, S El Arifeen, M Koenig. How should we measure maternal mortality in the developing world? A comparison of household deaths and sibling history approaches. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 84: 2006; 173–180.

- C Stanton, N Abderrahim, K Hill. An assessment of DHS maternal mortality indicators. Studies in Family Planning. 31: 2000; 111–123.

- D Vadnais, A Kols, N Abderrahim. Women’s lives and experiences: changes in the past 10 years. 2006; ORC Macro: Calverton MD.

- World Health Organization. Making pregnancy safer: the critical role of the skilled attendant. Joint statement by WHO, ICM and FIGO. 2004; WHO: Geneva.

- World Health Organization. Proportion of births attended by a skilled attendant: 2007 updates. Factsheet. 2007; Department of Reproductive Health and Research, WHO: Geneva.

- C Stanton, AK Blanc, T Croft. Skilled care at birth in the developing world: progress to date and strategies for expanding coverage. Journal of Biosocial Science. 39(1): 2007; 109–120.

- A Paxton, P Bailey, SM Lubis. Global patterns in availability of emergency obstetric care. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 93(3): 2006; 300–307.

- AL Fort, MT Kothari, N Abderrahim. Postpartum care: levels and determinants in developing countries. DHS Comparative Reports No.15. 2006; Macro International: Calverton MD.

- MA Koenig, K Jamil, PK Streatfield. Maternal health and care-seeking behaviour in Bangladesh: findings from a national survey. International Family Planning Perspectives. 33(2): 2007; 75–82.

- M Collumbien, M Gerressu, J Cleland. Non-use and use of ineffective methods of contraception. M Ezzati, AD Loez, A Rodgers. Comparative Quantification of Health Risks: Global and Regional Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risk Factors. 2004; WHO: Geneva, 1255–1320.

- G Sedgh, R Hussain, A Bankole. Women with unmet need for contraception in developing countries and their reasons for not using a method. 2007; Guttmacher Institute: New York.

- World Health Organization. Unsafe Abortion: Global and Regional Estimates of the Incidence of Unsafe Abortion and Associated Mortality in 2000. 5th ed., 2004; WHO: Geneva.

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2007. 2007; WHO: Geneva.

- World Bank. Data and research. At: <www.web.worldbank.org>. Accessed 3 September 2007

- EM McClure, RL Goldenberg, CM Bann. Maternal mortality, stillbirth and measures of obstetric care in developing and developed countries. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 96: 2007; 139–146.

- K Hill, R Thomas, C AbouZhar. Global estimates of levels and trends in maternal mortality: 1990–2005. Lancet. 2007(Forthcoming)