Abstract

A study in 2000–2001 of causes of death of women of reproductive age (15–49) in the West Bank, Palestinian Occupied Territories, found that 154 of the 411 deceased women aged 15–49 with known marital status were single. Death notification forms for reported deaths were analysed and verbal autopsies carried out, where possible, with relatives of the deceased women. We found important differences in the age at death and causes of death among the single and married women, which can be attributed to the disadvantaged social status of single women in Palestinian society, exacerbated by the current unstable political situation. 41% of the deceased single women were under 25 years of age at death compared to 8% of the married women. The proportion of violent deaths and suicides among the single women was almost twice as high as among the married women, mainly in those below age 25. The single women were also more likely to die from medical conditions which indicated that they faced barriers to accessing health care. The fieldwork was conducted at the height of the Intifada and the Israeli military response, with heavy restrictions on mobility, limiting the possibility of probing deeper into the circumstances surrounding sensitive deaths. More research into the socio-cultural context of single women in Palestine society is needed as a basis for intervention.

Résumé

En 2000-2001, une étude des causes de mortalité des femmes en âge de procréer (15-49) dans la Rive occidentale (Territoires palestiniens occupés) a révélé que 154 des 411 femmes décédées dans cette tranche d’âge et l’état civil était connu étaient célibataires. Nous avons analysé les formulaires de déclaration des décès et procédé à des autopsies verbales, si possible avec des parents de la morte. D’importantes différences apparaissaient dans l’âge au moment du décès et les causes de décès chez les femmes célibataires et mariées, pouvant être attribuées au statut social défavorisé des femmes célibataires dans la société palestinienne, exacerbé par l’instabilité de la situation politique. Au moment du décès, 41% des femmes célibataires avaient moins de 25 ans contre 8% des femmes mariées. La proportion de morts violentes et de suicides chez les femmes célibataires était près de deux fois plus élevée que chez les femmes mariées, principalement chez les moins de 25 ans. Les célibataires couraient aussi davantage de risque de succomber à des affections médicales, ce qui est révélateur des obstacles qui entravent leur accès aux soins de santé. Le travail sur le terrain a été mené au plus fort de l’intifada et de la réponse militaire israélienne, ce qui a nettement restreint la mobilité et la possibilité d’étudier plus profondément les circonstances entourant les décès sensibles. Davantage de recherches sur le contexte socioculturel des femmes célibataires dans la société palestinienne sont nécessaires comme base des interventions.

Resumen

En un estudio de las causas de muertes de mujeres en edad reproductiva (15–49) en Cisjordania, Territorios Palestinos Ocupados, realizado en 2000–2001, se encontró que 154 de las 411 mujeres fallecidas, de 15 a 49 años de edad, con estado civil conocido eran solteras. Se analizaron los formularios de notificación de defunción de las muertes y, donde fue posible, se realizaron autopsias verbales con los familiares de las difuntas. Se encontraron importantes diferencias en la edad al morir y las causas de muerte entre las mujeres solteras y casadas, lo cual puede atribuirse a la condición social desfavorecida de las solteras en la sociedad palestina, exacerbada por la situación política inestable actual. El 41% de las mujeres solteras fallecidas eran menores de 25 años de edad al morir, comparado con el 8% de las casadas. La proporción de muertes violentas y suicidios entre las solteras fue casi el doble que entre las casadas, principalmente en aquéllas menores de 25 años. Las mujeres solteras también eran más propensas a morir de problemas médicos, lo cual indica que afrontaban barreras para acceder a la atención médica. El trabajo en el campo fue realizado en plena Intifada y respuesta militar israelí, con marcadas restricciones sobre la movilidad, lo cual limitó la posibilidad de indagar más sobre las circunstancias en torno a las muertes sensibles. Para tener una base de intervención, es necesario realizar más investigaciones sobre el contexto sociocultural de las mujeres solteras en Palestina.

In most societies in the Arab world, women’s identity and social status are closely linked to marriage and the ability to bear children, which provide important avenues to a woman’s “social, emotional and economic security”.Citation1 Single womenFootnote* lack this recognition. Hence, early marriage, early pregnancy and high fertility have been typical among young Arab womenCitation1 until recent years. There is currently a trend towards increased age at marriage in many Arab countries both as a result of improved education and work opportunities for women,Citation2 and because of economic deterioration and the rising cost of housing.Citation3 However, some countries in the region still show high rates of early marriage. For example, the median age at first marriage in Oman is 17.5 years, in Saudi Arabia 19.5 and United Arab Emirates 18.6.Citation4 In the West Bank, in 2000, 17.2% of married women were under the age of 20,Citation5 while in 2004, this proportion had dropped to 12.2%.Citation6

In Palestinian society, if a woman passes her late 20s without getting married she is labelled A’nes, meaning that she is usually considered to have moved beyond marriageable age and is seen to be of less worth in the eyes of the community, especially in rural communities. Furthermore, a single woman in these conservative communities is constrained in her daily activities and her social interactions and relationships. In a report on the living conditions of Palestinians, marital status was emphasised as a factor of profound importance in assessing women’s situation. Married women usually fared better than unmarried women of all ages in terms of having independent economic resources and the ability to move around.Citation7 In spite of these differences, data on the health status of single Arab women are rare,Citation8 and population-based data on single women in the West Bank, Occupied Palestinian Territories, are entirely lacking.

Physical and financial access to health care and the quality of services provided are ever-growing challenges for Palestinian women because of the volatile political situation. Increasing poverty and massive unemployment have made health care far less affordable. The precarious situation of Palestinian women is also illustrated by the fact that female-headed households, which represent almost 10% of all Palestinian households, are significantly poorer than male-headed households.Citation9

The current cycle of violence in the Occupied Palestinian Territories started in September 2000 and continues at this writing. Increased levels of stress, restrictions on mobility and socio-economic hardship in the area are associated with the continuing political violence. A World Bank report from March 2003 showed that 60% of the population of the West Bank and Gaza lived under the poverty line of US$2 per day.Citation10 The numbers of poor tripled from 637,000 in September 2000 to nearly two million in March 2003. This has been extremely detrimental for the whole society.

In the process of analysing the data from a larger study on maternal death among women of reproductive age (15–49) in the West Bank in 2000–2001,Citation11 we found that one-third of the women who had died were single and that most of them were under 25 years of age at death. Considering the compromised social status of single women in Palestinian society, we felt these findings were worthy of further analysis. This paper, then, examines the causes of death of the single women who died in that two-year period as compared to the married women, and discusses the findings within the socio-cultural and political context of single women’s lives.

Subjects and methods

The subjects of this study were the total number of single (n=154) women of reproductive age whose deaths were reported to the public health departments in the ten districts of the West Bank between January 2000 and December 2001. In each of these districts, the person responsible for district statistics was assigned by the district public health department to receive all death notification forms. The family member(s) who notified the death were informed about the purpose of the study and asked whether they would agree to be interviewed in the deceased woman’s home. All except two gave their verbal consent. During the course of the study, severe political unrest prevailed in the West Bank and tight restrictions on mobility within and between districts interfered with the research. For this reason data collection was extended for six months until June 2002, to allow for delays in notification of deaths that had occurred during the two-year study period.

To validate the adequacy of notification, double checks were made with village health workers in the 68 Village Health Rooms in Hebron District, the largest district in the West Bank, and in visits to seven of the eight government hospitals in the West Bank. During these visits, all records of deceased women of reproductive age were checked. As a result, 20 women were found whose deaths had not been notified to a district public health department. The reported causes of these deaths were cancer (8 cases), pyelonephritis (1), renal failure (3), cardiovascular conditions (4), maternal death (1), hormonal disorder (1) and burns (2). As marital status was not noted in the hospital death summary sheets and it was difficult to follow up with the families, none of these cases could be included in this study. It is likely that the failure to report these deaths was due mainly to the fact that the women had been referred to specialist centres located in districts other than the ones where they lived, and that the reporting mechanism between the hospitals and the relevant district public health department was inadequate. Thus, we do not expect that these deaths would distort the analysis of the single women’s deaths.

For the verbal autopsies, a semi-structured questionnaire was designed with general identification questions and specific questions for each case of death and events that surrounded the death, based on the World Health Organization guidelines on verbal autopsies for maternal deaths.Citation12 The questionnaire consisted of four parts: (a) general questions that applied to all reproductive age deaths, i.e. education, occupation and marital status of the deceased woman; (b) questions related to the identified maternal deaths; (c) questions related to the non-maternal deaths; and (d) questions related to the children under five years of age of the deceased woman. One open-ended narrative question on what happened before and around the death was asked to explore family members’ perception of the illness or event that led to the death and their views on the cause of death. The questionnaire was piloted with 15 cases of reproductive age women who had died in January 2000 and minor modifications were made. The 15 women were then included in the larger study.Citation11

The interviewers were qualified public health nurses and physicians who were staff members at the public health department and well acquainted with the study area and culture. They attended a four-day training course on communication skills and interviewing techniques that addressed the sensitivity of the topic and ethical aspects. The interviews were initially planned to be carried out four to six weeks following each woman’s death, in order to respect the feelings of the bereaved family. However, due to the prevailing instability and delayed death notification, they were in fact carried out an average of ten weeks after the deaths (range 4–16 weeks), mostly in the homes of the deceased women. The exceptions were seven families who could not be visited due to security problems and two cases due to the unwillingness of the families with a suspected “honour killing”. In these nine cases, the interviews were conducted with the deceased woman’s close relatives who visited the public health department for other reasons, or through phone calls with a family member. Written consent was given in all cases, either signed by a family member or given verbally by those who were interviewed by phone.

Data from the verbal autopsies were analysed systematically by reviewing the background information, the sequence of events preceding and associated with the deaths, health status history, treatment-seeking pattern, quality of health care provided and the cause of death from the interviewee’s point of view. The final categorisation of the cause of death was based on the death notification report and double-checked against the verbal autopsy report. The two reports matched satisfactorily for all cases, including for the category of “injuries and accidents”.

Autopsies might have been carried out in a number of cases, but we had no access to this information either from the families or the Forensic Medicine Departments, for reasons of confidentiality. In Palestinian society, autopsy is frequently associated with an “unnatural” or criminal death and considered to be disrespectful towards the deceased. No questions about whether deaths of the single women were pregnancy-related were put to the families either, as this would have been seen as culturally offensive.

The Palestinian Ministry of Health endorsed the study and facilitated its implementation. Ethical approval was obtained from the Palestinian Helsinki Committee, which is entrusted to review research conducted in the Occupied Territories.

Results

Socio-demographic information about the women

Over the two-year period, 431 deaths of women of reproductive age reported in the ten districts of the West Bank were identified and investigated. Among them, 257 women had been married and 154 single. There was an increase in deaths among single women by 48% between 2000 and 2001 and 6% among married women. Of the single women, 62 died in 2000 and 92 in 2001, and of the married women 125 and 132 died in 2000 and 2001, respectively. Over 70% of the single women had lived in villages or small towns, 16% in cities and 12% in the Palestinian refugee camps. Of the married women, 70% had lived in villages or small towns, 21% in cities and 9% in Palestine refugee camps.

One fourth of the single women were illiterate, compared to 7% of the married women. A similar proportion of the single and married women had gone to school for 7–12 years (42% and 45%) or had a university education (6% and 8%). Eleven per cent of the single women had been students and 16% had been skilled or semi-skilled workers, while none of the married women had been students and 9% had been employed outside the home. One-third of the deceased single women and most of the deceased married women had not been working outside the home for income, but were responsible for the housework (in Arabic Rabbat Manzel).

The death rate in the year 2000 was 39 per 100,000 single women and 45 per 100,000 married women aged 15–49. Rates for 2001 could not be calculated as the total female population by marital status in 2001 was not available.

Age at death

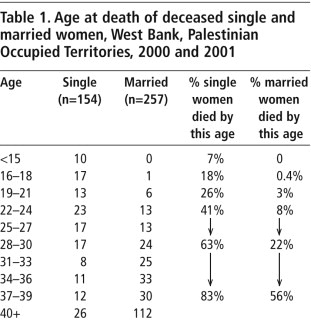

Many more of the single women died before the age of 25 than of the married women. Table 1 shows that of the single women, 18% were 18 years or younger at death. Only one of the married women died that young. 26% of the single women died by age 21 and 41% by age 25, compared to 3% and 8% respectively among the married women. Almost half of the deaths (44%) among the married women occurred at age 40 and above, compared to only 17% among the single women.

Place of death

It is generally perceived that taking a sick or injured person to hospital or at least attempting to do so indicates that the family has made an effort to save their life, and perhaps indicative of how much the family values the person concerned. We therefore looked at place of death in relation to medical causes of death and deaths due to injury or accident.

Forty-seven per cent of the single women with a medical cause of death had died in or on the way to a hospital or health unit, 48% at home and 5% outside the home. Of the married women with a medical cause of death, 61% had died in or on the way to a hospital or health unit, 36% at home and 2% outside the home.

Of the 15% of single women whose deaths were due to injury or accident, about 58% died in or on the way to a hospital or health unit, 17% at home and about one-fourth outside the home. Of the married women who died due to injury or accidents, 57% died in or on the way to a hospital or health unit, 14% at home and 29% outside the home. Hence, there was no significant difference between the married and single women as regards place of death.

Causes of death

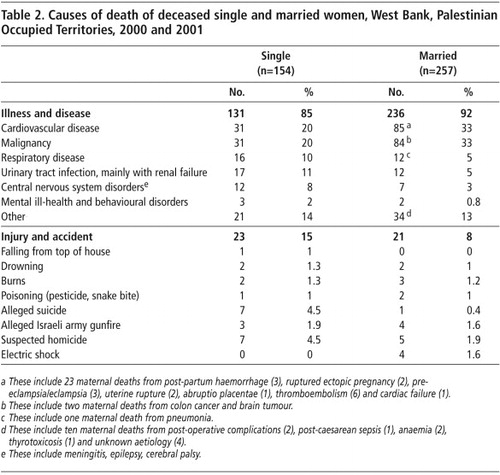

A large majority of the deceased women, 85% of the single women and 92% of the married women, were considered to be ill by their families prior to death. The two most commonly reported causes of death among the single women (Table 2) were malignancies (20%) and cardiovascular disease (20%), which were also the most common causes of death among the married women (33% malignancies and 33% cardiovascular disease). Fourteen per cent of the deaths in the married women were maternal deaths. No maternal deaths were reported among the single women. Even if there had been any such deaths, this cause would most probably not have been reported or recorded, as pre-marital sexual relations among single women are taboo.

Deaths due to urinary tract infection leading mainly to renal failure, mental health problems (e.g. mental retardation, behavioural disorders), central nervous system disorders (e.g. epilepsy, cerebral palsy) and respiratory diseases were about twice as common among the single women as the married women. For other diseases (including infections, endocrine and metabolic disorders, intestinal and liver diseases, musculo-skeletal disease, congenitial malformation and chromosomal diseases), there was no significant difference between single and married women.

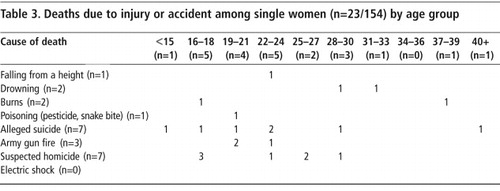

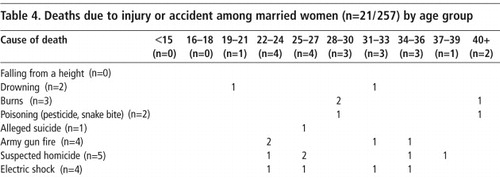

After malignancies and cardiovascular diseases, the third most common causes of death were injuries and accidents (Tables 2Tables 3Tables 4), of which there were almost double the rate in the single women (15%) as in the married women (8%). In addition, as Tables 3 and 4 show, there were more deaths due to accident and injury among the young single women than among the young married women, implying that in at least some cases these deaths were related to being single. Overall, based on the available information, there was less suspicion of foul play in the accidents and injuries that led to the deaths of the married women than in the deaths of the single women.

The most commonly alleged causes of injury and accidental death among the single women were suicide (4.5%) and homicide (4.5%). Comparatively fewer married women committed suicide (0.4%) or were murdered (1.9%). Looking at these deaths by age as well as marital status, we found that of the 63 single women who died under the age of 25, four (6.3%) were allegedly murdered and five (7.9%) allegedly committed suicide, whereas of the married women under age 25, none were said to have committed suicide and only one was allegedly murdered.

Another six deaths in single women (4%) and seven deaths in married women (2.7%) were allegedly due to drowning, burns, poisoning or falling from the top of a house. Four married women (1.6%) died from electric shock. The details ascertained about these deaths are as follows.

Two of the single women drowned. One was a 19-year-old university student who was accidentally drowned in the sea during a student group outing to the seashore. The other was 33 years old and had a psychiatric disorder. She went to collect water from a nearby well early in the morning and did not come back. They found her shoes near the well and saw that she had fallen into the well. The cause of death was listed as asphyxia due to drowning; it was not clear whether an autopsy was performed or not. One married woman also died from drowning in a well. The forensic report showed that she had fallen on her knees before she fell into the well.

A 23-year-old single woman died due to falling from the top of her house. The family said that she had “mental problems”. Mentally and physically handicapped women are potentially more vulnerable to both exploitation and abuse.

Two of the single women died from burns. One was 38 years old and caught on fire while making sweet biscuits on a feast evening after her brother poured inflammable liquid onto the fire. She died in hospital eight hours later from third-degree burns. The other was a 17-year-old woman who caught on fire while taking a bath, when the gas tube became detached. She died 16 days later at home. It was not clear why she had been discharged from hospital. Three married women also died from burns when they caught on fire while cooking.

The cases of homicide included two single sisters aged 18 and 25 years old who were killed in daylight by gunfire (many bullets to the head and body) inside their house. An autopsy was performed on both. When the father was interviewed two months later, he claimed not to have any idea why or who committed the crime.

Two single women aged 24 and 16 died in “honour killings”; no interviews could be obtained with their families. Two married women also died in “honour killings”. One, aged 25 when she died, had been raped and forced to marry the man who raped her. He abused and abandoned her and she decided to return to her family home. She was stabbed to death by her brothers. The other was a 35-year-old woman whose father killed her by stabbing her in her abdomen because she had become pregnant after being divorced. No further details could be obtained.

A 19-year-old single woman died of pesticide poisoning which occurred while the family were sprinkling the crops in the fields. Another 18-year-old single woman was shot in the head. Her male cousin was playing with a gun and pulled the trigger and shot her while pointing the gun at her head when she refused to put her hands up.

Four married women died due to electric shock. Two were accidents, caused by old washing machines. Another was planned by the husband, who intentionally exposed the electric wires on the washing machine to kill his wife. The last was a mentally disturbed women who was electrocuted with her husband by lightning on a rainy night in the metal hut they lived in.

Case histories of single women who died due to injury or accident

The following case histories, for which we were able to obtain more detail, illustrate the vulnerability of young, single women and show that they, like others in the community, are also victims of the volatile situation and political instability.

After completing secondary school, SS’s mother arranged her engagement to a young man from her village. The couple failed to get along with each other and soon decided not to marry. SS became very isolated and depressed. She wanted to marry one of her cousins but the family refused. She made several failed suicide attempts, became hostile to her mother (her father lived in another country) and was treated by a psychiatrist. One day she went to the city, bought and took rat poison and died the same day in hospital. (SS, single, 23 years old, secondary school education, unemployed)

Pre-arranged marriages are still common in rural areas, and the family’s refusal to let SS marry the man of her choice was the apparent reason for her suicide. It was difficult to get further information from the mother, who was interviewed. No autopsy was performed. In most of the other cases of alleged suicide, however, it was not clear from the interview what had actually happened, as in the following history of a sudden death reported by the deceased women’s sister:

The deceased had not complained of any illness. One afternoon during the fasting month of Ramadan, she suddenly started screaming and complained of abdominal pain. She was immediately taken to hospital, where she died an hour later. An autopsy was performed, confirming that death was due to a drug overdose [type of drug not recorded]. (SM, single, 29 years old, teacher)

In the interview, the deceased woman’s sister assured the interviewer that her sister had been a “very well-behaved person”. She claimed that it was difficult to say whether her sister had committed suicide or it was something else. The sister indicated that there had been rumours of sexual abuse by a close relative, which is a very serious matter in a family. Although no further investigations could be made in this case, if a case of sexual abuse within the family is disclosed, this would have a devastating influence on the family’s reputation in the community. They would be isolated and stigmatised. In such conditions, and especially when the victim dares to disclose the act, the best option for the perpetrator (or the family) is to get rid of the victim.

Seven single women were shot dead either by their father, a relative or an “unknown person”. Two of these cases were described as “honour killing” by the family, due to alleged “misconduct” of the woman.

AD and her sister were assaulted by some men in the street one day, and AD was hit over the head with a pistol. She was taken to hospital and stitched. The next day she was assaulted at her workplace by someone whom her sister described as an unknown man, who shot her with two bullets in the chest. She died that same day in hospital. (AD, single, 26 years, secondary school education, working in the family business)

In this case, the sister who was interviewed had herself been assaulted, and she was still in shock and fearful. The interview with her was difficult to arrange, and she gave only very general information. The reason for the killing remained unclear, and no further investigation could be made due to the volatile situation.

Three single women and four married women were allegedly shot dead by Israeli soldiers during the incursions and military actions that prevailed in the area during the study, such as this single woman:

AAL was standing in front of the door outside her home at sunset when, according to the family, she was shot in the chest by a bullet from a nearby Israeli settlement. She died on the spot. No investigations could be made by the family. (AAL, single, 20 years old, high school education, unemployed)

Discussion

In this analysis of the causes of death of all women of reproductive age deceased in the West Bank in 2000–2001, we found differences in the causes of death between single and married women, which we attribute at least in part to the disadvantaged social status of single women in Palestinian society, exacerbated by the current unstable political situation.

It should be noted that the single women may have differed from the married women in ways that could explain both why they remained single (and were perhaps considered unmarriageable) and why they died, i.e. due to serious mental and/or physical health problems. However, the limitations of our findings made it impossible to discern this with any certainty.

Of the medical causes of death, a high proportion of deaths due to urinary tract infections ended in renal failure. Renal failure among the single women, which is double the rate among the married women, may be attributed to long-standing, untreated infections with fatal complications (of the 17 women who died of urinary system disorders, 15 had renal failure) Inability to seek medical attention for gynaecological and urinary tract problems and menstrual irregularities, due to social constraints, was noted in another study among young unmarried women living in the old city of Nablus in the West Bank, who complained of their inability to obtain medical care.Citation13 In this study, single women were described by the interviewees as socially handicapped in seeking adequate care, even when it was available. Inability to access appropriate health care may also apply to the higher rate of deaths due to respiratory infections (chiefly pneumonia) noted among the single women in this study.

With family members of women who died due to injury or accident who agreed to be interviewed, the interviewer attempted to probe the circumstances of the death. This was sometimes very difficult due to the tense political situation, compromised law and order and/or the sensitive nature of the deaths.

In a situation with very limited law and order, people can more easily commit crimes and get away with them. At the same time, people become more mistrustful and cautious, as they feel unsafe. These conditions made the process of interviewing people, especially regarding possible suicide and homicide, but also other accidental deaths, uncomfortable for both interviewee and interviewer alike. In some cases, detailed information was provided by the deceased family; in others only general and superficial information could be obtained, and in two cases the interview was not welcome at all. Frequently, the interviewer had to accept whatever small amount of information the interviewee provided, without being able to probe or enquire about details. People frequently saw the interview as a form of interrogation about something the family preferred to forget – often for more than one reason. Therefore, it was critical that they did not risk admitting anything incriminating, particularly with regard to suspicious deaths. The only mitigating factor was that the interviewers were well known to many of the families in relation to their work in the public health department.

While it is not our intention to make accusations and despite the difficult conditions, there were many unanswered questions surrounding the circumstances of the deaths of single women, that is, whether the deceased had fallen, thrown herself or been pushed from a height or into a well, and whether she had committed or been pushed to commit suicide.

In some cases, the family did not appear to know what lay behind an apparent suicide. Sometimes the death was clearly very sensitive and the informant was unwilling or afraid to disclose more information. There were at least three cases of alleged suicide among the single women which could have been due to a perceived breach of “family honour”. Family honour in Palestinian society, as in many traditional societies in the region, is determined by the “respectability” of its women.Citation14 In a recent United Nations report, the term “honour suicide” is used for “suicides that appeared to be ‘honour killings’ disguised as suicide or an accident”.Citation15 Similar cases were found in a study in rural Bangladesh, where physical and mental abuse by fathers and other relatives often preceded both the suicide and murder of young, not-married women.Citation16 A recent Human Rights Watch report notes that “the killing of female relatives under the guise of family honour is a serious physical threat to Palestinian women in the West Bank and Gaza. A woman’s life is at risk if she is suspected of engaging in behaviour her family considers taboo”.Citation17 According to the same report, based on a large number of interviews with social workers, policemen, attorneys, women’s rights activists and ordinary women and men, “honour suicide” and “honour-based killing”, i.e. homicide, are a large and probably greatly under-reported problem in the Occupied Territories, regarded as a family affair to be kept within the confines of the home. Our findings suggest that this problem may be especially pronounced among young, single women.

BarzelattoCitation18 suggested that gender-based violence is promoted by the absence of peaceful resolution of conflict and increasing relative deprivation and frustration, which seems to be an apt description of the current situation in the Palestinian Occupied Territories. According to a study in 2002 by the Refugee Women’s Resource Project, 90% of respondents perceived that violence against women had increased as a result of the deteriorating political, social and economic situation in the Occupied Territories.Citation19 Human Rights Watch points out that the legal and social obstacles for Palestinian women reporting violence and seeking redress, which are huge even under normal conditions, are even greater with the current political unrest and the weakening of the legislative system.Citation17

In conclusion, the observed differences in causes of death between the deceased single and married women highlight critical issues regarding the status and condition of women in general and of single women in particular in Palestinian society. Certain direct medical causes of death among the single women, like urinary tract and respiratory infections, may indicate restricted access to health services. The health care-seeking patterns of single women should be further explored and attention paid to barriers to appropriate reproductive and other health care. The higher proportion of violent deaths and suicide among the deceased single women is a serious indication of their vulnerability, particularly given the societal stress prevailing in Palestine at present.

This study was conducted under conditions of severe mobility restriction and security problems due to political unrest during the entire period of study. This imposed serious limitations on the collection of qualitative information from the families of the women who had died. Further qualitative research into the causes and circumstances of single women’s deaths is needed to provide a basis for intervention.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the families of the deceased women for their co-operation and readiness to provide information. The Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA) financed this study. We are indebted to the Palestinian Ministry of Health officials and staff at both central and district primary health care and hospital settings for assistance and facilitation of our study.

Notes

* For the purposes of this study, single is defined as never married.

References

- H Zurayk, H Sholkamy, N Younis. Women’s health in the Arab world: a holistic policy perspective. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 58: 1997; 13–21.

- A Aoyaoma. Reproductive health in the Middle East and North Africa: well being for all. Human Development Network, Health, Nutrition and Population Series. June. 2001; World Bank Publications.

- D Singerman, B Ibrahim. The cost of marriage in Egypt: a hidden variable in the new Arab demography. The New Arab Family, Cairo Papers in Social Sciences. 24: 2001; 80–116.

- DeJong J, Shepard B, Mortagy I, et al. The reproductive health of young people in the Middle East and North Africa. Paper presented at IUSSP Conference, Tours, France, July 2005.

- Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. Health Survey: Main Findings. November. 2000

- Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. Demographic and Health Survey: Main Findings. 2004

- Heiberg M, Avensen G, Abu-Libdeh H, et al. Palestinian Society in Gaza, West Bank and Arab Jerusalem: a Survey of Living Conditions. Fagbevegelsens Senter for Forskning Report 151. 1992.

- H Rashad, M Osman, F Rudi-Fahimi. Marriage in the Arab World. September. 2005; Population Reference Bureau: Washington.

- Christian Aid. Losing ground: Israel, poverty and the Palestinians. 2003. At: <www.christian-aid.org.uk/indepth. >. Accessed 18 April 2006.

- World Bank. World Bank Report highlights 60 per cent poverty level in Palestinian Territories. Press release No.2003/241/MNA. March 2003.

- N Al-Adili, A Johansson, S Bergström. Maternal mortality among Palestinian women in the West Bank. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 93(2): 2006; 164–170.

- Campbell O, Ronsmans C. Report on the World Health Organization workshop held at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 10–13 January 1994.

- R Giacaman, M Odeh. Between the physical and psycho-social: women’s perception of health in the old city of Nablus. 1993; Berzeit University: Berzeit.

- S Ruggi. Honor killing in Palestine: Mediterranean women. At: <www.Mediterraneans.org/article.php3?id_article=63. >.

- D Bilefsky. How to avoid honor killing in Turkey?. New York Times. 16 July. 2006

- MK Ahmad, JV Ginneken, A Razzaque. Violent deaths among women of reproductive age in rural Bangladesh. Social Science and Medicine. 59: 2004; 311–319.

- Violence against Palestinian women and girls. Human Rights Watch Report. 10(7): November. 2006. At: <http://hrw.org/reports/2006/opt1106. >.

- J Barzelatto. Understanding sexual and reproductive violence: an overview. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 63(Suppl.1): 1998; S13–S18.

- Domestic violence against Palestinian women rises. Middle East Times. 20 September. 2002