Abstract

To improve access to maternal health care and family planning services in conflict-stricken Maguindanao province, southern Philippines, several non-governmental organisations have begun collaborating with local public health services. This exploratory study describes the experiences of local government service providers and two NGOs in a context of long-standing internal armed conflict, how and to what extent provision has been affected by the conflict and what has been done to overcome its effects. It is based on interviews with six health service coordinators and providers. Local government–NGO partnership takes the form of giving NGOs space in government health care facilities and receiving from them critical supplies, personnel and contraceptives. Service delivery structures have generally been spared from direct attacks by the parties involved locally in armed conflict due to the perceived benefits of their services, including for rebels and their families, their neutral stance and willingness to treat everyone. However, they do suffer from occasional disruption and kidnappings and need to seek protection from local leaders. When mass evacuation is required providers follow displaced families to evacuation points to ensure they continue to get services. Collaboration for maternal health care provision is recent, but the planned expansion of NGO projects will help it to evolve.

Résumé

Pour élargir l’accès à la santé maternelle et à la planification familiale dans la province de Maguindanao touchée par un conflit, au sud des Philippines, plusieurs ONG collaborent avec les autorités sanitaires locales. Cette étude exploratoire décrit l’expérience des prestataires des services publics locaux et de deux ONG dans un contexte de guerre civile ancienne. Elle se demande comment et dans quelle mesure les prestations ont été influencées par le conflit et ce qui a été fait pour en surmonter les effets. Elle est fondée sur des entretiens avec six coordonnateurs et prestataires de services de santé. Dans le cadre du partenariat entre les ONG et les autorités locales, les ONG reçoivent un espace dans les centres de santé publics et elles mettent à disposition des fournitures essentielles, du personnel et des contraceptifs. Les centres de santé ont généralement été épargnés par les attaques directes des combattants locaux grâce aux avantages perçus de ces services, y compris pour les rebelles et leurs familles, à leur neutralité et à leur volonté de traiter tout le monde. Les structures souffrent cependant de troubles occasionnels et d’enlèvements, et doivent demander la protection des chefs locaux. Quand une évacuation massive est nécessaire, les prestataires suivent les familles déplacées dans les points d’évacuation pour continuer à assurer les services. La collaboration en matière de santé maternelle est récente, mais l’expansion prévue des projets des ONG l’aidera à évoluer.

Resumen

Varias organizaciones no gubernamentales han empezado a colaborar con servicios locales de salud pública para mejorar el acceso a los servicios de salud materna y planificación familiar en la provincia filipina de Maguindanao, asolada por conflicto. En este estudio exploratorio se describen las experiencias de prestadores de servicios del gobierno local y dos ONG en un contexto de largo conflicto armado interno, cómo y hasta qué punto el conflicto ha afectado la prestación de servicios y qué se ha hecho para superar sus efectos. Se basa en entrevistas con seis coordinadores y prestadores de servicios de salud. La alianza entre el gobierno y las ONG locales consiste en dar a las ONG espacio en los establecimientos de salud gubernamentales y recibir de ellas suministros, personal y anticonceptivos esenciales. Las estructuras de prestación de servicios, por lo general, no han sido atacadas por las partes involucradas en el conflicto armado a nivel local, debido a los beneficios de sus servicios – incluso para los rebeldes y sus familias – su posición neutral y su buena voluntad para atender a todos. Sin embargo, de vez en cuando sufren trastornos y secuestros, lo cual las obliga a buscar protección en los líderes locales. Cuando es necesaria una evacuación de masas, los prestadores de servicios siguen a las familias desplazadas hasta los puntos de evacuación para asegurarse de que continúen recibiendo servicios. La colaboración en la prestación de servicios de salud materna es reciente, pero ésta evolucionará con la ampliación de los proyectos de las ONG.

While millions of Filipino women have improved maternal health as a result of improved access to health services, some 2.49 million women out of 12.4 million currently married women have remained in poor health due to lack of access to services or restricted access. There is a large unmet need for family planning,Citation1 and of the more than 400,000 induced abortions a year, many of which are unsafe, 80,000 result in complications.Citation2 Although budgetary constraintsCitation3Citation4 and poor quality servicesCitation5Citation6 help to explain Filipino women’s lack of access to care and poor maternal health, these problems are also complicated by internal armed conflicts. These conflicts involve the official Philippines armed forces and dissident armed forces (excluding internal disturbances such as riots, isolated and sporadic acts of violence and other similar acts).Citation7 Internal conflicts are pursued by “multiple actors with interdependent interests” and are driven by ideology and the desire to control resources, ethnicity, religion, greed, power distribution and leadership issues.Citation8

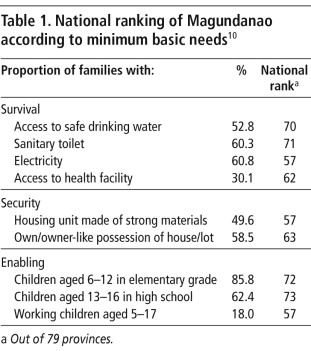

Internal armed conflict has been continuing in Maguindanao province, southern Philippines (). Maguindanao is one of five provinces in the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao, whose literacy rate (62.9%) is the country’s lowestCitation9 and poverty level (68.8%) the highest.Citation10 The region is predominantly Muslim (90% of 3.3 million population compared to 85% Catholic in the Philippines as a whole). It is governed by Muslim leaders independently from national government in most matters, except defence and security. The region decides how to spend its nationally-allocated funding (2008: US$205 million, or US$62 per capita)Citation11 but in its current budget it has been unresponsive to health needs.Citation12 Only 50–60% have access to safe drinking water, sanitary toilet and electricity, less than a third have access to a health facility and almost one in five children aged 5–17 is working (Table 1).

Table 1 National ranking of Maguindanao according to minimum basic needsCitation10

Maguindanao’s internal armed conflict has involved mainly the government’s armed forces and two groups, the Moro National Liberation Front (hereafter called the National Front) and Moro Islamic Liberation Front (hereafter called the Islamic Front). These Muslim secessionist groups seek the Southern Philippines’ transformation into Bangsa Moro (the country of Moro). In 1996, after 25 years of conflict, the national government reached a peace agreement with the National Front;Citation13 the Islamic Front is the current major source of armed dissidence. This situation is complicated by armed fighting among the province’s warring families or rido, consisting of a series of killings through the generations, arising from affronts and disgrace to the honour of one or more families or their members”. In 1970–2004, 218 clan conflicts were reported in the region (10 from Maguindanao). Rido stems from land disputes, political rivalries, and petty crimes and disagreements.Citation14

The government’s armed encounters with Islamic Front have caused disability, displacement and death for thousands of civilians and non-civilians alike. In a 2006 provincial incident, “17,392 persons or 3,065 families [were] evacuated to their relatives’ houses and other safe places”.Citation15 Rido casualties are many and countless.Citation14 These events are human security issues but, more importantly, broad development issues. Hence, in the early 2000s, the government, with donor agencies, resolved to address the province’s development gaps.Citation16

The strengthening of maternal health care services, of which family planning and pregnancy care are the core components, forms part of provincial development efforts. This is because of poor access to maternal health care, and the need for improved service delivery conditions across the region. Table 2 contains some health indicators among women in Maguindanao and the Autonomous Region. There is a far lower level of contraceptive use in spite of unmet need, far less use of antenatal care than in the rest of the country and a much higher maternal mortality ratio.

Currently, health service providers include the government’s Integrated Provincial Health Office and three non-governmental organisations (NGOs) (Personal communication, Agnes Sampulna, Maguindanao Department of Health, 21 February 2008), as core and support providers, respectively.

Foreign funding, the major source of Maguindanao’s and the country’s social programmes, is stable,Citation16Citation17 and there is evidence that the number of NGO providers may increase. Given the conflict setting, it is important that new providers can learn from organisations with relevant service delivery experience. It is important for them to know how and to what extent provision is affected by the armed conflict, and what strategies have been used to reduce its effects. This was an exploratory study and describes the experiences of the public health system and two selected NGOs in providing services in the context of internal armed conflict, how and to what extent provision is affected by conflict and what has been done to address its effects, based on interviews with selected organisational informants. Reproductive health service providers in other conflict-affected countries may also find these strategies useful.

Research and participants

Data were from the government’s Integrated Provincial Health Office and two NGOs – Agricultural Cooperative Development International and Volunteers in Overseas Cooperative Assistance, and Community and Family Services International. These two NGOs were chosen because of their service delivery experience in Maguindanao.

Two key informants, the coordinator of service delivery and a service provider, were interviewed from each institution. Being at the helm of service provision, their accounts are important and will hopefully lay the ground for a broader investigation among people seeking services and other local actors. Prior to the interviews, I briefed providers and coordinators about the purpose of the research and obtained their consent for taping the interviews. Questions covered the maternal health services offered by their organisation, their organisational experience of the armed conflict and the effects on service delivery, and the strategies they have adopted to address the effects of conflict. The interviews were conducted in English.

The six informants, all women, as are most health service providers locally, had 3–45 years of maternal health care service delivery experience in Maguindanao. They had been formally trained as medical technologists, midwives, nurses and social workers. The government services respondents were Muslim and Catholic, those from the Cooperative were both Catholic and those from Family International both Muslims.

Integrated Provincial Health Office experience

The Integrated Provincial Health Office is the provincial arm of the national Department of Health, guaranteeing Filipinos equitable, sustainable and quality health. The Department has some programmes exclusively or partially focused on providing the following sexual and reproductive health services: adolescent and youth health and development, natural and modern family planning, HIV/AIDS care, safe motherhood and women’s health.Citation23 In terms of maternal health care, it offers family planning and pregnancy care services and supplies (including those related to sexually transmitted infections) at all levels across the province’s 33 municipalities. Its total annual personnel and operations budget is US$1.83 million (Personal communication, Agnes Sampulna, Maguindanao Department of Health, 14 January 2008).

At the provincial level, the services are delivered through a hospital, at the municipal level through a rural health unit and at the village level through a village health station. One medical doctor serves 3–4 municipalities, one midwife 3–4 villages and one volunteer health worker for every village health station. The Office has 446 paid personnel, including health professionals (approximately 80% are Muslim women). The Office predominantly serves single and married Muslim mothers of reproductive age. To ensure quality services, the Office conducts training and in-service training for providers.

The Office has seen the government’s control of the province deteriorate over time. Previously, the Philippines armed forces were in total control of all municipalities but eventually lost some to the Islamic Front. Today this dissident group occupies and exercises sovereignty over an undisclosed number of municipalities. The Office noted that armed encounters between the government and the Islamic Front continue in all the municipalities it serves, albeit with varying frequency and intensity. In the early 2000s, when the government waged an all-out war against the Islamic Front, encounters were frequent and intense. With ongoing peace talks, their occurrence has diminished.

Although attacks remain common in all municipalities, the Office indicated that its health facilities and personnel have rarely been targeted by the Islamic Front. On a few occasions, some of its health centres were burnt down or forcibly taken by Islamic Front forces attempting to wrest control of a municipality, and some health staff were kidnapped and held hostage. Some of the kidnappings, along with car theft, terrorism and “revolutionary tax” collection, are committed by breakaway groups of the Islamic Front (and the National Front). Some of these incidents have victimised health personnel, which the Office treat as cases of “mistaken identity”. The Office considers that the warring forces respect its existence and operations. “We are the only ones able to penetrate the remotest villages.” The Office explained that they have not been under any direct attack because they are non-discriminatory: their providers serve everyone, including dissident residents. Furthermore, the Office refrains from reporting the whereabouts of any dissident patients to the government.

The most disruptive aspects affecting service provision have happened during government military offensives to regain control of camps and municipalities from the Islamic Front. These highly armed offensives have forced civilians to evacuate to safe locations such as community halls, school buildings and houses of friends and relatives in other towns. The period of evacuation is usually unpredictable (from a few days to a month). During long periods of evacuation, the Office “loses” some of its regular patients, including women in need of pregnancy and family planning assistance, who migrate to other towns. In some areas, civilian evacuations have been due not to military operations but to armed conflict between political groups, e.g. the latest skirmish related to local elections in May 2007.

During military offensives and political conflicts, logistical operations, including provision of supplies to evacuation centres, are hampered. The Office informants said that their supplies are given safe passage during lull periods in the encounters, particularly during military operations. Operations of the hospital, based in the provincial capital, are seldom affected. No instances of rape or sexual offences had been documented in the evacuation centres: “The utmost concerns of evacuees are basic needs of survival, and fear of gunshots and conflict. They are tense with what is happening to them.”

In the event of rare direct attacks against its health facilities, specifically the abduction of providers, the Office coordinates with the Islamic Front. Recalling the kidnapping of its workers by the Front, one informant said that she immediately phoned the Front leader and explained to him that the victims were women’s health care providers. Two hours later he ordered the workers’ release, “even apologising for the mistake”. While Office providers had no power regarding military offensives or other conflict, they were able to learn from their community-based providers about when these were likely to occur. During civilian evacuation due to military operations, the Office is directly involved.

“Our providers follow where our patients evacuate to – day and night. We always offer quality services even there… We are sensitive to evacuees’ needs. One time, we had to put up a make-shift ‘motel’ room in the evacuation centre to accommodate couples’ sexual needs.”

Office informants supported coordination and cooperation with NGOs who had begun working in the province because the government services could help them find out people’s needs. They also highlighted the importance of gaining broad social support from women’s organisations and (male) groups of religious leaders, farmers, drivers and men in uniform.

Agricultural Cooperative Development International and Volunteers in Overseas Cooperative Assistance

As a non-profit, United States-based organisation since 1963, the Cooperative has promoted broad-based economic growth and the development of civil society in emerging democracies and developing countries.Citation24 In the past three years (2004–2007), while maintaining its central office in Manila, the organisation has been providing family planning and pregnancy care services in Maguindanao through its recently completed “Enhanced and Rapid Improvement of Community Health” project. It is continuing these services, among others, via its new “Sustainable Health Improvements through Empowerment and Local Development” project. The Cooperative conceived these projects based on observation from its previous agricultural work in Maguindanao of women’s extremely poor maternal health status.

The Cooperative’s maternal health care work in Maguindanao is not its first in the Philippines. Two years earlier, it implemented a similar project in the region’s other conflict-laden provinces. In Maguindanao, to the end of 2007, the Cooperative served five municipalities, two identified as in conflict and three as “generally peaceful”. By 2008, its geographic coverage for the new second project will be province-wide. In these five sites to date, the Cooperative has provided women with modern contraceptives, Pap smears, antenatal, delivery and post-natal services, and counselling. A five-member field team (medical doctor, nurse, midwife, medical technologist and computer programmer), all Muslims, have led the Maguindanao-wide service provision. The Cooperative maintains links with the government’s Integrated Provincial Health Office: their service channels are based in the Office’s rural health units and their staff have offices in the Office’s headquarters. The Healthy Family Coalition that the Cooperative has organised, which is a community-based advocacy group, includes providers from the Office as well as Muslim religious leaders and local government workers along with their own representatives.

In the project’s three years, none of its affiliated rural health units had been ransacked nor had their coalition members, women patients or own personnel been attacked or harmed by the Islamic Front. They explained that the dissidents and their female relations had in fact benefited from the organisation’s neutrality: “Anyone, regardless of their affiliations or even a rebel, is accepted in our facilities. We do not choose whom to serve.” Moreover, the Cooperative informants added that it was an advantage to have mostly women in the coalition and as staff: “Rebels respect women. Islam prohibits hurting them.”

This NGO reported that its services were disrupted many times during armed confrontations between government and Islamic Front forces in rural residential communities. Armed conflict occurred because of territorial encroachment by either group into the other’s occupied municipalities to gain or re-gain territorial control. In these fierce battles, services were halted and residents, many of whom were the NGO’s patients, had to be evacuated to safe locations, usually for several weeks. The organisation underscored that armed conflicts in its project sites had gone beyond the government and rebel forces, with the generations-long rido conflicts between and among clans also causing forced civilian evacuations.

Although its health facilities have not been attacked by the Islamic Front, the Cooperative informants said they took safety and preventive measures for their personnel and coalition members. By networking with other agencies, the organisation collected information on potential outbreaks of armed hostility. It used this knowledge in scheduling outreach activities such as community assemblies in safe places, while avoiding areas reported as risky and in organising evacuations. It attempted to compensate for service delivery gaps during evacuations resulting from armed hostilities by transferring its services to evacuation sites. At the sites, the Cooperative provided women with family planning methods and pregnancy care services.

The Cooperative has three main tenets regarding their relationship to the armed conflict that direct its work. One, that the project should benefit women, families and communities: “Once rebels see the benefits, they will respect and support it.” Two, that provision should be coupled with income-generating activities led by women’s associations. Three, that new entrants to the area should not underestimate the Islamic Front’s capacity to wreak havoc and destruction; setting the project’s geographic boundaries is vital: “Do not go to rebel-controlled territories.”

Community and Family Services International (CFSI)

Committed to the psychosocial dimensions of peace and social development internationally, CFSI seeks: a) to empower and equip uprooted people and others in exceptionally difficult circumstances to address and prevent social and health problems; and b) to prevent children, women and men from being uprooted by promoting peace, respect for human rights and equitable distribution of resources.Citation25 Their central office is in Manila and the field office for their entire operations is in a city neighbouring Maguindanao. The field office has 23 contracted employees and community-based partners, 16 teachers and six “family support workers” who were trained in-house. Eight of the ten field office workers are Muslims (sex ratio: four women to one man).

Since 2005, CFSI, with the Consuelo Foundation, another NGO, has been serving pregnant Muslim women of all ages in one village under its child survival-related Healthy Start Project. The village, with 521 families, has been the organisation’s project site since 2001 (a site in which evacuation camps resulting from 2000–2001 and 2003 conflict-related displacements were set up). Since then, the village has been the recipient of CFSI’s infrastructure projects, such as a school building erected with community volunteers, and now its Healthy Start Project (implemented by an eight-member, all-Muslim team). The project was born out of the findings of a minimum basic needs survey, which suggested that the village’s pregnant women have pressing unmet family planning needs: 48% were non-users of contraceptives, 39% were using the lactational amenorrhoea method while 13% were pill and injectable users.

CFSI does not have its own health centre, nor does it use the Office’s rural health units for operations. However, along with its family support workers, CFSI utilises the Office’s medical and paramedical personnel for delivering antenatal, natal and post-natal services to its family beneficiaries. Moreover, CFSI coordinates closely with the Office’s rural health units and has representatives from the Office on its technical working group. In spite of the findings of the needs assessment survey, CFSI does not directly promote or provide modern contraceptives to women, for religious reasons. However, they do refer potential contraceptive users to the Office. In the context of Islam, CFSI modifies common terminology to suit local needs, e.g. by using “birth spacing” instead of “family planning” and “relationships” for “gender”. Moreover, CFSI and the Office, in coordination with other groups such as the World Food Programme, provide food and nutrition advice to mothers. To date, the Healthy Start Project has already achieved its target for 2005–07 of 122 family beneficiaries among the site’s 521 families.

In 2003, both the government and the Islamic Front declared the project’s site to be a peace zone, an outcome of advocacy by CFSI and community residents. Since then, armed encounters between government and Islamic Front forces have not occurred. Prior to the declaration, when the previous national government had an all-out war policy against the Islamic Front, there was community-wide suffering because of relentless armed confrontations. Houses were burned (including that of an informant), and residents were evacuated. Given its start-up date in 2005, the NGO’s project has avoided the atrocities and consequences of the pre-2003 armed incidents.

Although clashes between the government and Islamic Front have now ceased in the village (and in the whole municipality), CFSI informants reported that the community is still beset by armed clashes between rival political groups. They estimate that each year the village experiences about three such incidents, during which residents are displaced and evacuated to school buildings and neighbouring communities (one incident reportedly displaced 3,000 families, including the project site’s 521 families). One informant recalled a large-scale armed incident that affected even the evacuation centre: “Evacuees were again displaced; they ran and found their way through to a highway to reach a relatively safe municipality.” Along with families, the project personnel also get caught in the crossfire and their lives are threatened. Informants underscored that dislocation of CFSI beneficiaries and staff from their usual residential and work environments had resulted in serious disruptions to service delivery.

Where armed political fighting and displacement occur, CFSI shifts its strategy for provision in ways very similar to the Office: “We follow the displaced families to evacuation points. They get the services, and their morale is boosted.” This strategy was deemed critical because of the need to follow up pregnant women’s needs, including for nutrition: “Just when our beneficiaries have improved nutritional health, the armed conflict would ensue and disrupt the process. We intervened in the evacuation centre to sustain programme gains.” Due to displacement from political fighting, the organisation has already “lost” 12 of its 122 family beneficiaries to other municipalities. Little is known as to whether these former clients are receiving the same health services elsewhere.

CFSI informants stressed the importance of coordination with the military and dissident forces for security reasons and informing them of planned services. They emphasised that the reason why the Islamic Front respects their project work is that it is regarded as beneficial to Muslim women and children, some of whom are members of dissidents’ families. Confident of its work experience in the conflict setting of Maguindanao, CFSI plans to replicate the project among indigenous peoples in other municipalities.

Discussion

The delivery of family planning and pregnancy care services is critical to address Maguindanao women’s poor maternal health status. Attuned to the provincial development plan, the Office aims to strengthen its service delivery resources, for instance, through regular in-service training for its providers. However, public funds for staff and operations are scarce, with only US$2.28 per person as the annual budget allocation, resulting in a ratio of one health provider per 1,796 population. This is the reason the Office collaborates with private sector providers, such as with the two NGOs described here.

The resulting local government–NGO partnership takes the form of the Office sharing its facilities and providers with NGOs and receiving back from the NGOs critical supplies of other personnel and contraceptives, which enhances service delivery. For a number of reasons, these health services are all generally spared from direct attacks by warring groups due to the perceived benefits of their services for community residents, including rebels and their families, as well as the providers’ non-discriminatory and neutral stance and willingness to treat all patients. Internal armed conflict blurs the distinction between combatants and civilians.Citation26 Thus, providers are able to maintain low visibility and to survive and work effectively through the conflict, by staying neutral. Finally, the relative immunity of health services from attack may be because most of the providers are female and Muslim.

Also relevant is the Office’s special relationship and leverage for conflict-related negotiations with Islamic Front, an outcome possibly rooted in the Office’s decades-old advocacy and its Muslim constituency. Its links with the Islamic Front position the Office as a critical partner rather than an adversary, thus perhaps helping to protect its associated NGO partners from direct assault as well. In addition, the earlier work of the two NGOs (farming and infrastructure development) seems to have created trust within the communities and thus helped to prevent direct attacks on their facilities and staff.

On the other hand, while integrating service delivery with the community’s broad life concerns is effective,Citation3 neither the Office nor its NGO partners have control over the inevitable disruptions to services and civilians’ lives when military, rebel, political or clan conflicts result in head-on armed collision in communities. The Office’s independent and collaborative service provision during such emergencies fills the void by ensuring the transfer of services to evacuation centres in order to respond to evacuees’ needs.

The Office–NGO collaboration consists of providing services for pregnancy care (e.g. health forum, abdominal palpation, medical check-up, weight measurement, hospital or facility-based delivery and management of post-natal complications) and family planning (e.g. supply and delivery of some modern contraceptives such as pills and condoms), and training providers in these areas. The partnership is recent, and although it might already have improved the health of some women, its services, resources and performance are still being developed. Given the extent and magnitude of poor maternal health practices and conditions in the province,Citation27Citation28 it will take some time before there is great enough improvement in these respects. However, the planned expansion of NGO projects will help the partnership to evolve. One area requiring further planning concerns the selection of municipalities in which to carry out collaborative service provision, and also the delineation of organisational roles at regular and evacuation centre-based service delivery points. Another relates to ensuring that patients normally served in one facility but “lost” during evacuations are able to receive services elsewhere. A third is building links with other government agencies who can provide information about the potential for outbreaks of hostility, military forces, dissident groups, warring political parties and families, and community-based groups, both men’s groups and particularly local women’s organisations. Collaborative partnerships can discuss ways and means to advocate for and harness health resources and to sustain the province’s peace and security efforts. Multi-sector cooperation is critical in finding peaceful solutions for resolving conflict.Citation12

One major problem in the current situation is the severe limitations on provision of pregnancy care services (for instance, iron and folate supplementation, tetanus toxoid, facility-based delivery care and management of complications), modern contraceptives (for example, emergency oral contraceptives), and the absence of both sexuality education and abortion-related services. Despite planned programmes in the area of family planning, sexual and reproductive health are not a priority in Maguindanao because of political, administrative, policy and religious constraints, alongside lack of knowledge and attitudinal and behavioural constraints.Citation12 These obstacles are also prevalent elsewhere in the Philippines due to the power of the Catholic church and the current government’s commitment to conservative policies.Citation2

Table 2 Health indicators among women in Maguindanao and the Autonomous Region of Muslim MindanaoCitation18–22

This study of reproductive health service provision in the conflict-ridden setting of Maguindanao is a preliminary one, and its findings are limited due to the exclusive focus on purposively selected health service coordinators and providers. In future research, it will be useful to gather data from service records and field observations as well as interviews with rebels, political groups and clans, and, critically, women requiring services who have experienced conflict and evacuation. Nonetheless, the study offers insights into the conditions under which maternal health and family planning services may secure protection from direct attack and from harm to staff through a stance of neutrality, an ethic of service to all regardless of affiliation, and government–NGO collaboration.

Acknowledgements

I thank Vladimir Fernandez and Noraida Abdullah Karim for facilitating the conduct of interviews. Special thanks go to informants from the Office, the Cooperative and CFSI.

References

- National Statistics Office. 2005 Family Planning Survey. 2005; National Statistics Office: Manila.

- World Organisation Against Torture. State Violence in the Philippines: An Alternative Report to the Human Rights Committee. 2003; World Organisation Against Torture: Geneva.

- RB Lee, P Dodson. Filipino Men’s Involvement in Women’s Health Initiatives: Status, Challenges and Prospects. 1998; Philippine Council for Health Research and Development: Manila.

- AB Reyes. Women 2000: Gender Equality, Development and Peace for the Twenty-First Century. 2000; Republic of the Philippines: New York.

- Asian Development Bank. Policy for the Health Sector. 1999; ADB: Manila.

- SE Rogan, MV Olveña. Factors Affecting Maternal Health Utilization in the Philippines. 2004; National Statistics Office: Manila.

- Amnesty International; Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa. Monitoring and Investigating Human Rights Abuses in Armed Conflict. 2001; Russell Press: Basford UK.

- J Shambaugh, J Oglethorpe, R Ham, (with contributions from Sylvia Tognetti). The Trampled Grass: Mitigating the Impacts of Armed Conflict on the Environment. 2001; Biodiversity Support Program: Washington DC.

- National Statistics Office. 2003 Functional Literacy, Education and Mass Media Survey. 2005; NSO: Manila.

- National Statistics Office. 2000 Family Income and Expenditure Survey. Preliminary Results. Manila, 2000.

- About Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao: Agencies Department of Health. At: <http://armm.gov.ph/index.php?action=view&id=36&module=newsmodule&src%40random46032edc09c4f. >.

- M Fernandez, T Fernandez, P Gani. Evaluation of the Enhanced and Rapid Improvement of Community Health Project in the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao. 2004; POPTECH: Washington DC.

- Center for Humanitarian Dialogue. Philippines-Moro National Liberation Front. At: <www.hdcentre.org/Philippines-MNLF. >.

- Durante O, Gomez N, Sevilla E, et al. Management of Clan Conflict and Rido among the Tausu, Maguindanao, Maranao, Sama and Yakan Tribes. Zamboanga City, Philippines: Ateneo De Zamboanga University Research Center, and Cotabato City, Philippines: Notre Dame University Research Center, 2005.

- Citizens’ Disaster Response Center. Thousands flee as clashes start anew in Maguindanao and Bukidnon. Disaster Alert. 10: 2006; 1–3.

- Mindanao Economic Development Council. Local execs, donors agree to converge aid for econ, food security in Maguindanao. At: <www.medco.gov.ph/medcoweb/newsfeatl.asp?NewsMonthNo=5&...&NewsPageSize=10-14k. >.

- T Quismundo. US vows continued aid to South. Philippine Daily Inquirer. 3 August. 2007; 6.

- National Statistics Office. Annual Poverty Incidence Survey. 2002; NSO: Manila.

- National Statistics Office. Quickstat on Maguindanao. 2006; NSO: Manila.

- National Statistics Office. Quickstat – April 2007. 2007; NSO: Manila.

- National Statistics Office; ORC Macro. National Demographic and Health Survey Philippines. 2004; NSO/ORC Macro: Calverton MD.

- L Nicodemus, ME Alba, M Mateo. Women’s Health: Developing Indicators for Equity, Access and Quality of Women’s Reproductive Health Care in Family Medical Practice in Southeast Asia (Philippine Country Report). At: <www.rockmekong.org/pubs/Year2004/fmrg/chap3.pdf. >.

- Philippines Department of Health. Profile. At: <www.doh.gov.ph/about_doh/profile. >.

- Agricultural Cooperative Development International and Volunteers in Overseas Cooperative Assistance. About Us. At: <www.acdivoca.org/ACDIVOCA/PortalHub.nsf/ID/AboutUs. >.

- Community and Family Services International. Goals. At: <www.cfsi.ph/goals.htm. >.

- Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. SIPRI Yearbook 2001. 2001; SIPRI: Solona, Sweden.

- G Cruz, E Palaganas. 2006 United Nations Population Fund Baseline Survey Final Report. 2006; UNFPA: Manila.

- C Raymundo, E Laguna, J Sorita, E Casola. 2003 National Demographic Health Survey Further Analysis: Maternal Health Care Utilization and Health Seeking Behaviors. 2006; University of the Philippines Population Institute, Demographic Research and Development Foundation, National Statistics Office, Macro International: Manila.