Abstract

Israel offers nearly full funding for in vitro fertilisation (IVF) to any Israeli woman irrespective of her marital status or sexual orientation, until she has two children with her current partner. Consequently, Israeli women are the world’s most intensive consumers of IVF. This 2006 study explored the perceptions of Israeli IVF patients about the treatment and their experiences, probing possible links between state policy and women’s choices and health. Israeli women (n=137), all currently undergoing IVF, were invited to fill out questionnaires. The questionnaires were delivered in five IVF centres by university nursing students or by the clinics’ nurses. Most women were optimistic they would become pregnant, and described the treatment as having modest or no negative effects on their lives. They expressed a sweeping commitment to IVF, which they were willing to repeat “as many times as needed”. At the same time, the majority appeared to have very partial treatment-related knowledge and marginalised side effects, even though they had experienced some themselves. We interpret the observed favourable image of IVF as closely related to the encouragement implied in the extensive state funding of IVF and in the Jewish Israeli tradition of pronatalism, which may account for the virtual absence of critical public debate on the subject.

Résumé

Israël prend presque totalement en charge le financement de la fécondation in vitro (FIV) pour toute Israélienne, quel que soit son état civil ou son orientation sexuelle, jusqu’à ce qu’elle ait deux enfants avec son partenaire actuel. Par conséquent, les Israéliennes sont les plus fortes consommatrices de FIV au monde. Cette étude de 2006 a exploré leurs perceptions de la FIV et leurs expériences, testant des liens possibles de la politique étatique avec les choix et la santé des femmes. Des Israéliennes (n=137), qui effectuaient toutes une FIV, ont été invitées à remplir un questionnaire. Ce questionnaire a été remis dans cinq centres de FIV par des étudiants en soins infirmiers ou des infirmières du centre. La plupart des femmes étaient optimistes et pensaient qu’elles finiraient par tomber enceintes, et décrivaient le traitement comme ayant peu ou pas d’effets négatifs sur leur vie. Elles se déclaraient extrêmement favorables à la FIV, qu’elles souhaitaient répéter « autant de fois que nécessaire ». En même temps, la majorité d’entre elles semblaient avoir des connaissances très partielles du traitement et des effets secondaires, même si elles en avaient fait elles-mêmes l’expérience. Nous pensons que l’image favorable de la FIV est étroitement liée à l’encouragement implicite que suppose le large financement étatique de la FIV et à la tradition nataliste juive israélienne, qui peut expliquer l’absence quasi-totale de débat public critique sur le sujet.

Resumen

En Israel se ofrece casi todo el financiamiento necesario para la fertilización in vitro (FIV) a toda mujer israelí, independientemente de su estado civil u orientación sexual, hasta que tenga dos hijos con su pareja actual. Por consiguiente, las mujeres israelíes son las usuarias más intensas del mundo de FIV. En este estudio de 2006 se exploraron las percepciones de pacientes israelíes de FIV respecto al tratamiento y sus experiencias, y se indagó en cuanto a los posibles vínculos entre la política estatal y las opciones de las mujeres y la salud. Se invitó a las mujeres israelíes (n=137), todas ellas sometiéndose actualmente a la FIV, a llenar los cuestionarios. Estos fueron entregados a cinco centros de FIV por estudiantes universitarios de enfermería o por las enfermeras de las clínicas. La mayoría de las mujeres eran optimistas de que quedarían embarazadas, e informaron que el tratamiento tuvo un efecto moderado o ningún efecto negativo en su vida. Expresaron un amplio compromiso a la FIV, que estaban dispuestas a repetir “todas las veces que fuera necesario”. Al mismo tiempo, la mayoría parecía tener un conocimiento muy parcial del tratamiento y efectos secundarios marginados, aunque ellas mismas habían experimentado algunos. Interpretamos la imagen favorable de la FIV como algo estrechamente relacionado con la motivación implicada en el extenso financiamiento estatal de la FIV y en la tradición israelí judía de pronatalidad, que explicaría la virtual ausencia de debate público crítico al respecto.

Infertility affects between 8–14% of all reproductive-age couples worldwide.Citation1 In the Western world, reproductive medicine, often pivoting around in vitro fertilisation (IVF), has become a routine method to overcome the problem. The world’s most intensive consumers of IVF are Israeli women, whose fertility treatment is state-funded. Nearly unlimited treatment is offered to every woman, irrespective of her marital status or sexual orientation, until she has two children with her current partner. One consequence of this policy is women’s ability to undergo an extremely large number of IVF cycles, sometimes as many as 20 or more.Citation2

The following study probes the perceptions and experiences of Israeli IVF patients of the treatment they are undergoing, and considers them within the local context of unlimited state provision, Jewish religion and tradition, as well as contemporary Jewish Israeli history and politics. The country’s policy applies to all Israeli citizens, including the 20% mostly Muslim minority groups. While some non-Jewish women and couples rule out IVF on grounds of cultural and religious restrictions, others make ample use of these public services. However, owing to differences in history, religion and positionality, the Jewish and non-Jewish Israeli populations differ substantially in their reproductive behaviour. In the present paper, we limit our discussion to Jewish Israeli women only.

Despite some erosion of the traditional family, Jewish Israelis of all ethnic and class identities still marry more than their West European and North American counterparts; they do so at an earlier age, have fewer births out of wedlock and have lower rates of divorce.Citation3 Moreover, although Israel resembles European countries in levels of women’s education and labour market participation,Citation4 the total fertility rate of Israeli women is considerably higher than that of European women. Whereas in the UK and Italy the figures are 1.66 and 1.28 respectively, and the EU average is 1.47,Citation5 in Israel the total fertility rate, which declined from 3.8 in 1975 to 3.1 in 1985, was still as high as 2.84 in 2004.Citation6 Among Jewish women, total fertility rates have dropped from 3.39 to 2.79 to 2.62 in those same years. Nevertheless, Jewish Israelis still view childrearing as life’s greatest joy.Citation7

Israel’s reproductive policy is widely known as pronatalist, “Zionistically” associating reproduction with the Israeli–Palestinian conflict by declaring the enlargement of the state’s Jewish population an important component of nation-building. Local policies have indeed encouraged childbearing in various ways: soon after the state was founded, maternity benefits were the first to be distributed by the state. Shortly afterwards free maternity hospital care and birth grants were instituted. Workers in the public sector were remunerated in proportion to the number of their children (during the 1940s and 1950s); employed mothers were eligible for special tax reductions;Citation8 national awards were granted to “Heroine Mothers” who delivered their tenth child, and to “families blessed with many children”, as they were called.Citation9 Child allowances have gradually been raised and universalised and, for decades, increased with the number of children (i.e. the allowance for the fifth child is higher than for the first).Citation10 An explicit expression of this policy was provided in 1968, when the government-founded Demographics Center defined its goal as:

“Carry[ing] out a reproductive policy intended to create a psychologically favourable climate that will encourage and stimulate natality; an increase in natality in Israel being crucial for the future of the whole Jewish people.” Citation11

In the following decades, pregnant workers and women in fertility treatment gained legal protection from redundancy. The latter were also granted up to 80 days annual paid leave.Citation3 In some predominantly female employment areas (e.g. teaching), mothers were entitled to full-time payment and benefits for fewer hours. At the same time and in striking contrast, fertility control measures like contraceptives and abortion have always been only partly covered by the public health system, and sex education is markedly lacking.Citation10 Abortion, while reasonably available, requires a committee’s approval, which often entails humiliation of the applicant.Citation12

This pronatalist policy is one of the underpinnings of the centrality of “the family” in Israel. Policies reproduce and echo the values and interests which the state and other influential bodies have brought to bear during the manufacturing process. They shape people’s conduct, but they go beyond external behaviour, to influence perceptions and subjectivities, in ways that have medical, legal, economic and moral implications, and that encourage and legitimise certain life trajectories over others. With their goals mostly unstated, such policies may appear to be unrelated to ideology or politics, thus concealing their impact as a vehicle of power.Citation13 Our findings, however, which reveal substantial similarity between women’s perceptions of IVF and the state’s approach to reproduction as encapsulated in its policy, raise questions regarding the influence of this state policy on women’s perceptions, as well as their physical and mental well-being.

Israel’s state-sponsored pronatalism is implemented in a highly accommodating context, coinciding with historical, religious and cultural influences in the same direction. The biblical commandment to “be fruitful and multiply” constitutes reproduction as both a major goal in the individual’s life and a collective mission to be accomplished. Later processes, during the Diaspora era (namely, before the founding of Israel) have resulted in the equation of individual procreation with community survival. Collective strategies of survival were rooted in the familial body, rendering reproduction a collective pursuit.Citation14 The family was thus constituted as a locus of individual and collective reproduction.Citation15Citation16 In more recent years, childbearing became fraught with national conflicts. Following the Holocaust, family founding was constituted as a response to the Nazi extermination. Shortly afterwards, against the background of the escalating Israeli–Palestinian conflict, the Zionist ideology emphasised procreation as a means to ensure Jewish continuity and political survival, thereby constituting childbearing as a crucial contribution – rooted in the bodies of its female citizens – to the nation-building effort. At present, the political conflict has significantly receded as a motivation for childbearing in the local reproductive discourse.Citation17 Nevertheless, whereas Jewish Israelis view their children or the desire to have children as their own private wish, they still hold the state responsible for its citizens’ ability to conceive and to bear children.

The pronatalist bent is also manifested at the daily discourse level, in which marrying and raising children are construed as the “normal” accomplishment of mature adulthood. Commonly used idioms, like the “patriarchs and the matriarchs” (ha’avot veha’imahot) or the “children of Israel” (bnei Israel), hail a kinship-based collective belonging. Even the fiercely disputed claim on the land is legitimised through the tribal/familial/biblical myth of ancestry: the “land of our forefathers” (erets avotenu).

IVF in Israel

A prominent component of Israel’s state sponsored pronatalism is its uncommon policy regarding assisted reproductive technology noted above. These services, openly supported by politicians as a means of increasing the country’s Jewish population,Citation18 have always been publicly funded. Since 1981, when IVF was introduced in Israel, it too has been covered.

IVF and all related technologies, most notably intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), used to overcome male infertility, are offered free of charge to any Israeli woman up to the age of 45. The age limit rises to 51 if using donor eggs. No psychological, educational or financial requirements apply. State funding is limited to two children with the woman’s present partner (if she has one), irrespective of the number of her or the partner’s children from previous relationships. In practice, even this limitation can be exceeded and women who have more children (like nine women in the present study) still get substantial funding for treatment.

A different consequence of the high rates of IVF consumption, or possibly another motivating force behind the local policy, is Israel’s extensive research in the field. For decades now, professional accomplishments in this domain have been internationally acclaimed, and as such are a source of national pride and excellence.Citation19 Some scholars view the professionals’ lobby as a major power driving Israel’s exceptional state policy.Citation20

The support of politicians and professionals reverberates in the public sphere in Israel. The press occasionally writes about politicians defending challenges to the fertility treatment budget; health professionals voice the agony of “barren” women and couples desperate to start families,Citation18 and applaud the resolve and determination of women who “remained optimistic and… succeeded in making [their] dream come true” after 25 IVF cycles.Citation2 Women activists also struggle for IVF in the name of the human right to (genetic) parenthood. Implied in each case is the presumption that IVF is worth “fighting for”, constituting this medical technology as both the effective and morally appropriate response to infertility. The swift dismissal of the few dissenting voices that have pointed to the bodily toll of treatment has further enhanced this perception.Citation18

Lay Israelis, living in this social climate, seem to share the same perspective. With its diffuse religious, political and individual significance, the familial conviction has been profoundly internalised by Israeli Jews, rendering individual agency a crucial factor in the regulation and regeneration of the Jewish population in Israel.Citation21 Thus, for the women, public funding of IVF is a caring state’s response to their agony and needs. Indeed, in contrast to coercive pronatalist policies, like those that were enforced in Romania under Ceaucescu,Citation22 Israel’s reproductive policy is not viewed as mobilising individuals for the sake of state interests but rather as a generous state commitment to support its struggling citizens.

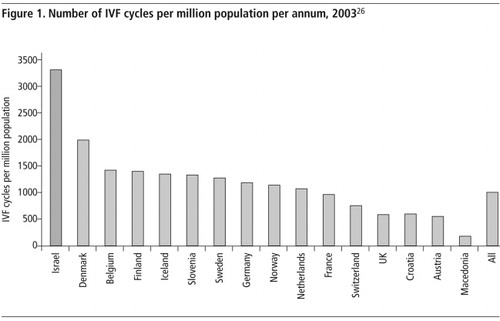

We view the availability and routinisation of IVF as highly value-laden. In Israel, where budgetary cuts are constantly on the news, the unlimited funding of fertility treatments sends out a strong message to women – and men – on the “infertile body” as flawed, yet reparable, with IVF its remedy. Within this climate, it is not surprising that the rate of usage of IVF in Israel far exceeds that of any other country (). In 2003, in a country whose population comprised 6,689,700 citizens,Citation23 including 2,463,900 women of reproductive age (15–44),Citation24 there were 22,449 cycles of IVF.Citation25

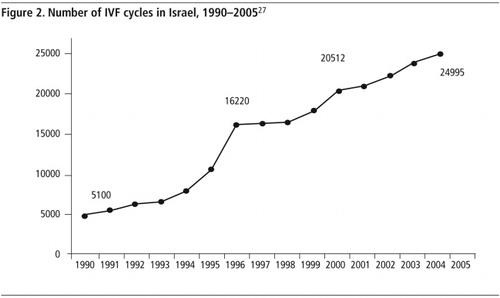

Moreover, extensive as it is, use of IVF in Israel keeps expanding. Between 1990 and 2005, the annual number of IVF cycles quintupled from roughly 5,100 to 25,000 (). A large part of the increase is attributable to the introduction of ICSI in the mid-1990s, which was added to the IVF treatment process, following which the combined treatments became the standard treatment for male infertility as well.

Treatment is provided by 22 IVF clinics. Success rates for each IVF clinic are collected by the Ministry of Health but are not made available to the public. Practitioners cite an overall figure of 16–20% “take-home baby” per treatment cycle. IVF can be combined with donor insemination and surrogacy, and is generally supported by local courts and religious authorities.Citation28Citation29

In line with its popularity, potential IVF complications have always been downplayed in the Israeli discourse. The dissenting voices of one or two physicians who have emphasised the treatment’s “weightiness” were dismissed as aiming to cut state costs at the expense of individuals’ welfare.Citation18 The political and professional interests involved, though occasionally acknowledged, are also pushed to the margins, let alone the idea that some women might be placed at risk by the consequences of this policy.

Noticeably, adoption, while available, is not nearly as popular or state-supported: domestic adoption is an exceedingly complicated bureaucratic process entailing roughly six years of waiting. This route to family formation is open only to heterosexual couples who comply with a long list of requirements. Inter-country adoption is available to a more diverse applicant population but costs roughly a whole year’s average Israeli income, which has to be paid fully out of pocket with no state assistance whatsoever.Citation30

Study methods

Research was conducted between March and May 2006, in five IVF units in the Haifa area in north Israel. Israeli women currently undergoing IVF were approached by a clinic nurse or doctor and were invited to fill out questionnaires. All Jewish Israeli women undergoing IVF or related treatment (e.g. ICSI) were approached; 147 women consented to participate. For the sake of methodological soundness, we excluded from the present analysis 10 non-Jewish Russian “reproductive tourists”, leaving 137 women in the study. Rates of consent to participate were not tracked systematically, but were assessed at 70–75% of the women approached. The questionnaires contained 49 open and multiple choice questions and were delivered by fourth year university nursing students or the clinic nurse. The main subjects addressed in the questionnaire were treatment history, alternative channels to resolving childlessness, impact of IVF on the woman’s life, treatment-related knowledge and its sources, treatment-related social networks, satisfaction with treatment and concerns regarding treatment. Basic socio-demographic details were also recorded. Questions were then clustered into 11 subject groups: acquaintance with IVF, consent form, commitment to IVF, determination to conceive, IVF impact on life, knowledge provision in clinic, IVF-related knowledge, need for additional knowledge, sharing and social support, and IVF team support. Links of potential interest were then probed for statistical correlations. Lastly, we were interested in the women’s exposure to and attitudes towards adoption as an alternative response to infertility. However, wishing to avoid possible injury to some women’s feelings we refrained from explicitly using the term and phrased open questions that allowed any woman who wanted to, to bring up this option. (e.g. Are you trying to materialise your wish for motherhood via other routes as well?)

Participants

Respondents’ ages spanned from 22–50 (average 33.7 years); 114 of the 137 women were married. Women were divided rather equally among the three self-described income categories of below, at or above the national average household income. Almost half of respondents had post-secondary education. Half defined themselves as secular, a third as traditional and the remaining sixth as observant religious Jews. Women varied greatly in the number of IVF treatment cycles they had undergone. 55% had had 1–3 cycles; 24% had had 4–8 cycles and 21% were undergoing their 8th–23rd cycle. The average was 4.75 cycles. In terms of aetiology of infertility, respondents were divided almost equally between female factors (32%), male factors (24%) and unexplained (32%) infertility. (These are not mutually exclusive.)

Findings

The majority of respondents accepted IVF as the normal way of overcoming infertility. When asked whether they were addressing the infertility problem also by non-medical methods, 84% of the respondents said no, and 86% said they had not considered any additional options either. Interestingly, of the 19 women (14%) who answered in the affirmative to the latter question, only seven said what those options were. Five mentioned supplementary medication; only two (1.5%) mentioned adoption. We read the high percentage of negative responses as a rejection, or perhaps distrust, of non-medical responses to infertility, including adoption.

A closer analysis of the data revealed that even among the 33 women over the age of 40, whose chances of conceiving with IVF were fairly slim, as many as 28% had never considered any alternative to medical technology. The same applied to 48% of the women who had undergone four IVF cycles or more and to the majority (56%) of the women who had been referred to IVF on grounds of unexplained or male infertility.

The extensive adherence of Israeli women to IVF needs to be considered also in the light of their assessment of the treatment’s efficacy. Though each and every woman in this study, like all IVF users in Israel, has signed a highly informative consent form, and though 89% of the respondents have experienced at least one IVF cycle prior to the current one, when asked, in an open question, what the likelihood of conception is in one IVF cycle, less than half the respondents (46%) gave realistic estimations (15–35%). Nearly a quarter (22.4%) thought the chance was 40–50% per cycle and 13% assessed the chances at 70–100%. Eight per cent said they did not know. The remaining 10.5% underestimated the likelihood of conception (0–10%). Overall, the majority of the women had an inaccurate perception of the likelihood of treatment success, with the bias notably in the optimistic direction.

Another aspect of the local faith in IVF was the calm regarding potential side effects. Over a third of the women were entirely untroubled by this possibility. Of the women who did acknowledge there were risks, less than 30% could list the major ones while the rest mentioned only a few or unrelated conditions. Altogether, only 23 (16%) of the 137 women provided well-informed answers regarding the risks associated with the treatment they were undertaking. (Knowledge levels correlated with women’s education level but not with any other socio-demographic or treatment-related variable.)

This optimistic approach becomes especially instructive given the women’s reports on their own IVF experience. Nearly two thirds of the women (61%) said they experienced some changes in their health over the last month (i.e., the treatment period), which they attributed (in an open question) to the medications (42%), the hormones, (15%), the treatment process (14%) or their fears (6%). (The remaining respondents did not specify a cause.) However, the vast majority (71%) did not report these side effects to the attending doctor.

However, the women expressed little interest in obtaining additional information regarding IVF. Fewer than 8% were very interested in expanding their knowledge and an additional 25% were only somewhat interested. The remaining two-thirds had no such desire. The lack of interest may well be attributed to the abundance of information in popular books, magazines and on the Internet. It may also suggest that the women prefer to sustain an optimistic outlook while undergoing a treatment that aims to fulfil a deep personal wish.

A hint in this direction was provided by the women’s reports on their lived experience of the treatment. In order to ascertain this aspect we devised a “perceived impact” score for every respondent. The score grouped together the replies to questions about whether the treatment incurred any financial costs, led to any change in the woman’s employment or in her life, and whether she had recently noted any change in her physical or mental well-being. The findings revealed that the majority of respondents perceived IVF to have a modest impact, if any, on their finances, employment, lifestyle and health. One quarter of the women reported a moderate effect and an additional third noted minimal to no consequences. (When changes were noted they were primarily in relation to health.) Even the number of treatment cycles a woman had undergone did not correlate significantly with perceived impact.

In order to better understand this response, we investigated its association with the respondents’ “commitment to IVF score”, which was extrapolated from the questions regarding alternatives to IVF in the women’s quest for motherhood. The analysis indeed revealed that this score was significantly associated with the “perceived impact” score. Thus, among women who were strongly committed to treatment only a few (6%) felt it had had a maximum impact on their lives. In contrast, 33% of the women who were least committed to IVF experienced the treatment as substantially interfering with their lives.

The respondents’ favourable attitudes towards IVF – their commitment to medical treatment over non-medical alternatives, their over-optimistic expectations of probable success and the low impact they felt it had on their lives – probably explain their unbounded dedication to the treatment. In answer to the open question: “How many IVF cycles would you be willing to undergo?”, 86% of respondents answered “as many as needed”. (The remaining women, who provided a finite figure, pivoted around 5–7 additional cycles.) Even among the small minority (17%) of women who felt strongly affected by IVF, nearly 70% were ready to undergo as many cycles as needed. This commitment cut across all levels of income, education, religiosity, family status, number of previous treatment cycles, support from family and professionals, and knowledge of IVF. It also applied equally to women who underwent IVF due to male infertility.

We find the relative homogeneity in the women’s dedication to IVF and in their experiences of it in itself highly instructive. Given the socio-demographic diversity of the respondents in this study and the depth of the social, ethnic and economic rifts within Israel, this finding suggests that in the field of fertility treatment, consensus is so broad as to homogenise perceptions and experiences of Israeli women from all walks of life who otherwise differ so significantly on so many other issues.

Discussion

Bodily experiences like that of infertility and its treatment are shaped by cultural, political and social environments that influence our definitions of the normal, the painful and the reparable. In Israel, where IVF has become so thoroughly normalised, the favourable views of the technology expressed by the women who have used it raise questions regarding the potential impact of these notions on their physical and mental well-being.

Routine as it may be, IVF is far from being a trivial medical intervention. Probably the most common complication is that of ovarian hyper-stimulation syndrome that affects 3–5% of women undergoing treatment. Normally manifesting as a transient abdominal discomfort, this condition may become life-threatening.Citation31 (In Israel, there has been one case of death following this problem. In two additional deaths of IVF patients the cause of death is disputed. All three cases, however, occurred over eight years ago.)

During pregnancy, increased rates of pregnancy-induced hypertension (pre-eclampsia) – again, normally treatable but potentially a life-threatening complication – have been documented among IVF users as compared to women who have conceived “naturally” (21% vs. 4%).Citation31 When more than one embryo is transferred – which is the standard practice in Israel – multiple births and the related problems of pre-term delivery and low birthweight are also more frequent.Citation32–34 Some studies have also reported a higher incidence of perinatal morbidity and mortality as well as congenital anomalies,Citation35–39 even when looking only at singleton births.Citation31 Most of these complications, as well as others, are listed in the Israeli consent form that has been produced by the Israeli Medical Association (ovarian hyper-stimulation syndrome, multiple birth, sensitivity to hormone treatment, ovarian torsion, tearing or bleeding that may necessitate surgery, menopausal symptoms and ovarian cysts.) Whereas these problems are generally rare in Israel, the risk is non-trivial, and often applies to women who undergo treatment without a definite fertility problem having been diagnosed in their own bodies.

Beyond the actual treatment period lies the as yet unconfirmed possibility that high levels of hormone stimulation through repeated cycles of IVF may contribute to breast cancer rates, which are already extremely high in Israel.Citation40–42 A report to Israeli politicians in 2005 said that “findings are inconclusive at this point, but the time span since the popularisation of IVF is not sufficient and foreign studies are not quite applicable to Israel, where the number of IVF cycles per woman is so much higher”.Citation43 The same report also called attention to the inadequacy of the Ministry of Health’s database (owing to financial limitations), in that it would not be able to provide data to further research on the subject.

While Israeli women’s optimism is probably adaptive in terms of helping them to endure the long intensive treatment, it may also expose them, especially if they are somewhat older or undergoing many treatment cycles, to possible risks of which they may not be aware. It is therefore important to unpack the favourable image expressed by those women who repeatedly seek IVF treatment.

We read the findings of the present study in the spirit of Shore and Wright’s contention that policies influence not only people’s conduct but also their subjectivities and beliefs, as echoing the local assisted reproduction policy of unlimited provision. Whereas the policy is evidently not the sole influence, the comprehensive funding warrants – not to say encourages – massive consumption of treatment, including by relatively older women; it implies the state’s faith in the treatment’s efficacy and induces women’s trust in it as well.

At the same time, by making adoption in Israel near to impossible and leaving international adoption applicants to fend for themselves in other countries, it marginalises this non-medical route to founding a family. It is not surprising then that women who have chosen to invest their bodies and years in IVF, express commitment to and faith in the technology. As illustrated by the women’s questionnaire responses, their private wishes fully coincide with those declared and implied in the state policy. Very cautiously, we would suggest that in some cases, the free and immediate availability of treatment may render withdrawal from the programme, although entirely voluntary, especially difficult. Taken to the extreme, Israel’s IVF policy may paradoxically result in restricting the range of reproductive choice, relegating childlessness or adoption to the very end of the list of what people consider to be acceptable options.

Having said that, it is vital to clarify that this paper by no means criticises state funding of fertility treatment. It rather calls attention to the consequences of unrestricted treatment. While IVF may well be highly beneficial and effective for some women, for others, primarily those with a family history of breast cancer, those who are older, and those who have undergone numerous unproductive cycles, whose chances of conception are comparatively small, it may incur health risks.

In conclusion we would mention some countervailing observations regarding Israel’s IVF landscape. At the political level, childbearing is becoming a highly personal affair, with fewer and fewer Israelis willing to think of their children in terms of state or national interests.Citation17 At the personal level, awareness of IVF risks may be starting to rise, as suggested by major articles in Israel’s main newspaper, reporting individual women’s experience with breast cancer occurring after IVFCitation44 and scientific findings suggesting the existence of an IVF–cancer link.Citation45 While possibly prompting a new discursive line, this latest article also included the subtitle: “I became ill but I don’t for a moment regret it”, thus hinting at the continuing complexity of the issues at hand.

References

- GR Bentley, N Mascie-Taylor. Infertility in the Modern World: Present and Future Prospects. 2000; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- D Even. Finally a mother [Hebrew]. Ma’ariv. 31 October 2005. At: <www.nrg.co.il/online/1/ART1/001/307.html. >. Accessed 27 January 2008.

- Birenbaum-Carmeli D, Carmeli YS. Introduction: Reproduction, medicine and the state: the Israeli case. In: Birenbaum-Carmeli D, Carmeli YS, editors. Kin, Gene, Community: Reproductive Technology among Jewish Israelis. Oxford: Berghahn Books. (Forthcoming).

- S Swirski, E Konor-Attias, B Swirski. Women in the Labor Force of the Israeli Welfare State [Hebrew]. 2001; Adva Centre: Tel-Aviv.

- The World Fact Book. Central Intelligence Agency. At: <https://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/fields/2127.html. >. Accessed 30 June 2007.

- Fertility rate, Israel. At: <www.cbs.gov.il/publications/lidot/lidot_all_1.pdf. >. Accessed 30 June 2007.

- A Glickman. Marriage in Israel on the threshold of the 21st century [Hebrew]. Public Opinion [De’ot Ba’am]. 7: 2003

- A Doron, RM Kramer. The Welfare State in Israel: The Evolution of Social Security Policy and Practice. 1992; Westview Press: Boulder CO, 119–140.

- H Barkai. The Evolution of Israel’s Social Security System: Structure, Time Pattern and Macroeconomic Impact. 1998; Ashgate: Aldershot. p.36/44/63.

- J Portugese. Fertility Policy in Israel: The Politics of Religion, Gender and Nation. 1998; Praeger: Westport CT, 91–149.

- The Demographics Centre Report. 1968. p.2.

- D Amir, O Biniamin. Abortion approval as a ritual of symbolic control. C Feinman. The Criminalization of a Woman’s Body. 1992; Harrington Park Press: New York, 5–16.

- C Shore, S Wright. Policy: a new field of anthropology. C Shore, S Wright. Anthropology of Policy: Critical Perspectives on Governance and Power. 1997; Routledge: London.

- M Safir. Religion, tradition and public policy give family first priority. B Swirski, MP Safir. Calling the Equality Bluff. 1991; Pergamon: New York, 57–65.

- J Katz. Tradition and Crisis: Jewish Society at the End of the Middle Ages. 1971; Schoken Books: New York.

- S Swirski. Community and the meaning of the modern state: the case of Israel. Jewish Journal of Sociology. 18: 1976; 123–140.

- Remennick L. Between reproductive citizenship and consumerism: attitudes towards assisted reproductive technologies among Jewish and Arab Israeli women. In: Birenbaum-Carmeli D, Carmeli YS, editors. Kin, Gene, Community: Reproductive Technology among Jewish Israelis. Oxford: Berghahn Books. (Forthcoming).

- D Birenbaum-Carmeli. “Cheaper than a newcomer”: on the political economy of IVF in Israel. Sociology of Health and Illness. 26(7): 2004; 897–924.

- D Birenbaum-Carmeli. Pioneering procreation: Israel’s first test-tube baby. Science as Culture. 6: 1997; 525–540.

- Hashash Y. Medicine and the State: The medicalization of Reproduction in Israel. In: Birenbaum-Carmeli , Carmeli YS, editors. Kin, Gene, Community: Reproductive Technology among Jewish Israelis, Oxford and New York: Berghahn Books. (Forthcoming).

- B Prainsack. “Negotiating life”: the regulation of human cloning and embryonic stem cell research in Israel. Social Studies of Science. 36(2): 2006; 173–205.

- G Kligman. The Politics of Duplicity: Controlling Reproduction in Ceausescu’s Romania. 1998; University of California Press: Berkeley.

- Central Bureau of Statistics. Israel Statistical Monthly No.2/2008, Population by Population Group, Table 1/20. At: <www.cbs.gov.il/www/yarhon/b1_h.htm. >. Accessed 27 January 2008.

- Central Bureau of Statistics. Population aged 15 and over by religion, marital status, sex, age and permanent type of locality. Israel Statistical Annual, 2005. Table 2.19. At: <www1.cbs.gov.il/reader/shnaton/shnatonh_new.htm?CYear=2005&Vol=56&CSubject=2. >. Accessed 27 January 2008.

- Internal document to doctors. Ministry of Health, 2004.

- A Nyboe Andersen, V Goossens, L Gianaroli. Assisted reproductive technology in Europe, 2003. Results generated from European registers by ESHRE. Human Reproduction. 22(6): 2007; 1513–1525.

- Israeli Ministry of Health, 2007.

- Shalev C, Lev B. Public funding for IVF in Israel – Ethical aspects, working paper, 1999.

- Kahn, SM. 2000. Reproducing Jews: A cultural account of assisted conception in Israel, Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2000.

- Birenbaum-Carmeli D, Carmeli YS. Adoption and assisted reproduction technologies: a comparative look at state policies. In: Birenbaum-Carmeli D, Carmeli YS, editors. Kin, Gene, Community: Reproductive Technologies among Jewish Israelis. Oxford: Berghahn Books. (Forthcoming).

- CP Tallo, B Vohr, W Oh. Maternal and neonatal morbidity associated with in vitro fertilization. Journal of Pediatrics. 127: 1995; 794–800.

- HB Westergaard, AM Johansen, K Erb. Danish national in vitro fertilization registry 1994 and 1995: a controlled study of births, malformations and cytogenetic findings. Human Reproduction. 14(7): 1999; 1896–1902.

- SE Buitendijk. Children after in vitro fertilization. An overview of the literature. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care. 15(1): 1999; 52–65.

- A Manoura, E Korakaki, S Bikouvarakis. Outcome of twin pregnancies after in vitro fertilization. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 83(11): 2004; 1079–1084.

- KC Olsen, KM Keppler-Noreuil, PA Romitti. In vitro fertilization is associated with an increase in major birth defects. Fertility and Sterility. 84(5): 2005; 1308–1315.

- R Klemetti, M Gissler, T Sevon. Children born after assisted fertilization have an increased rate of major congenital anomalies. Fertility and Sterility. 84(5): 2005; 1300–1307.

- AA Rimm, AC Katayama, M Diaz. A meta-analysis of controlled studies comparing major malformation rates in IVF And ICSI infants with naturally concieved children. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics. 21(12): 2004; 437–443.

- M Hansen, JJ Kurinczuk, C Bower. The risk of major birth defects after intra cytoplasmic sperm injection and in vitro fertilization. New England Journal of Medicine. 346(10): 2002; 725–730.

- M Ludwig, K Diedrich. Follow-up of children born after assisted reproductive technologies. Reproductive Biomedicine Online. 5(3): 2002; 317–322.

- Israel National Cancer Registry. Annual report updated Januaryn 2005. Israel Ministry of Health. At: <www.health.gov.il/. >. Accessed 27 January 2008.

- L Lerner-Geva, E Geva, JB Lessing. The possible association between in vitro fertilization treatments and cancer development. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 13: 2003; 23–27.

- I Pappo, L Lerner-Geva, A Halevy. The possible association between IVF and breast cancer incidence. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 15(4): 2008; 1048–1055.

- Dror Tomer. Risks in fertility treatments – breast cancer and other risks. Report submitted to MP Shaul Yahalom, 2005. At: <www.knesset.gov.il/MMM/data/docs/m01213.doc>. Accessed March 14, 2008.

- Levy-Barzilai, Vered. Is there a connection between fertility treatments and breast cancer? [Hebrew] Ha’aretz. 22 December 2004.

- Rosenblum S. The heavy price of fertility treatments [Hebrew]. Yedioth Aharonoth. 22 January 2008.