Abstract

The 20-year war in northern Uganda has resulted in up to 1.7 million people being internally displaced, and impoverishment and vulnerability to violence amongst the civilian population. This qualitative study examined the status of health services available for the survivors of gender-based violence in the Gulu district, northern Uganda. Semi-structured interviews were carried out in 2006 with 26 experts on gender-based violence and general health providers, and availability of medical supplies was reviewed. The Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) guidelines on gender-based violence interventions in humanitarian settings were used to prepare the interview guides and analyse the findings. Some legislation and programmes do exist on gender-based violence. However, health facilities lacked sufficiently qualified staff and medical supplies to adequately detect and manage survivors, and confidential treatment and counselling could not be ensured. There was inter-sectoral collaboration, but greater resources are required to increase coverage and effectiveness of services. Intimate partner violence, sexual abuse of girls aged under 18, sexual harassment and early and forced marriage may be more common than rape by strangers. As the IASC guidelines focus on sexual violence by strangers and do not address other forms of gender-based violence, we suggest the need to explore this issue further to determine whether a broader concept of gender-based violence should be incorporated into the guidelines.

Résumé

La guerre qui sévit depuis 20 ans au nord de l’Ouganda a déplacé jusqu’à 1,7 million de personnes à l’intérieur du pays, et appauvri la population civile, la rendant vulnérable à la violence. Cette étude qualitative a examiné les services de santé pour les victimes de violence sexiste dans le district de Gulu, au nord de l’Ouganda. Des entretiens semi-structurés ont été menés en 2006 avec 26 experts sur la violence sexiste et des soignants généralistes, et on a évalué la disponibilité des fournitures médicales. Les Directives du Comité permanent interorganisations (IASC) sur les interventions contre la violence sexiste dans les situations de crise humanitaire ont été utilisées pour préparer les guides d’entretien et analyser les données. Quelques lois et programmes traitent de la violence sexiste. Néanmoins, les centres de santé manquaient de personnel suffisamment qualifié et de fournitures médicales pour détecter et prendre correctement en charge les victimes ; le traitement et le conseil confidentiels ne pouvaient être garantis. Il existait une collaboration intersectorielle, mais davantage de ressources sont nécessaires pour élargir la couverture et relever l’efficacité des services. La violence du fait des partenaires intimes, l’abus sexuel de mineures, le harcèlement sexuel et les mariages précoces forcés sont peut-être plus fréquents que les viols perpétrés par des inconnus. Puisque les directives de l’IASC se centrent sur les actes de violence sexuelle d’inconnus et n’abordent pas d’autres formes de violence sexiste, nous pensons qu’il faut approfondir cette question pour déterminer s’il faut inclure un concept plus large de violence sexiste dans les directives.

Resumen

La guerra de 20 años en Uganda septentrional ha ocasionado el desplazamiento interno de 1.7 millones de personas, así como empobrecimiento y vulnerabilidad a la violencia entre la población civil. Este estudio cualitativo examinó el estado de los servicios de salud disponibles para las sobrevivientes de violencia basada en género, en el distrito Gulu de Uganda septentrional. En 2006, se realizaron entrevistas semiestructuradas con 26 expertos en violencia basada en género y prestadores de servicios de salud, y se analizó la disponibilidad de suministros médicos. A fin de preparar las guías de las entrevistas y analizar los resultados, se utilizaron las directrices del Comité Interinstitucional Permanente (IASC) respecto a las intervenciones relacionadas con la violencia basada en género en ámbitos humanitarios. Aunque existen algunos programas y legislación sobre este tipo de violencia, los establecimientos de salud carecían de personal suficientemente calificado y suministros médicos para detectar y manejar adecuadamente a las sobrevivientes, y no se podía garantizar tratamiento y consejería confidenciales. Hubo colaboración intersectorial, pero se necesitan más recursos para ampliar la cobertura y eficacia de los servicios. La violencia entre parejas íntimas, el abuso sexual de niñas menores de 18 años, el acoso sexual y el matrimonio temprano y forzado posiblemente sean más comunes que la violación perpetrada por extraños. Dado que las directrices del IASC se centran en la violencia sexual por extraños y no tratan otras formas de violencia basada en género, sugerimos explorar más este asunto para determinar si se debe incorporar en éstas un concepto más amplio de la violencia basada en género.

Gender-based violence is a serious human rights and public health concern globally. It includes sexual violence, sexual exploitation and abuse, forced prostitution, intimate partner violence, trafficking, forced and early marriage, and harmful traditional practices such as female genital mutilation.Citation1 The effects on health arising from gender-based violence include injuries, gynaecological disorders, unwanted pregnancy, adverse pregnancy outcomes, sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, mental distress and death.Citation2

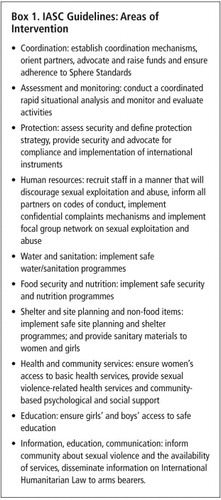

The Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), a forum for coordination, policy development and decision-making on humanitarian assistance, involving UN agencies and non-governmental organisations, finalised their Guidelines for Gender-Based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Settings (IASC guidelines) in 2005.Citation1 The purpose of the guidelines is to help humanitarian organisations to design, coordinate and implement a minimum set of activities in humanitarian emergencies for a more effective response to gender-based violence and prevention in ten intervention areas (Box 1). They focus on sexual violence during the early phase of an emergency, while recognising that other forms of gender-based violence should not be ignored. The IASC guidelines provide an opportunity to assess gender-based violence services against these internationally agreed standards.

A global evaluation on reproductive health among selected refugee and internally displaced populations in Uganda, Republic of Congo, Yemen and Chad concluded that services for survivors of gender-based violence were poor and inadequate for displaced populations.Citation3 In Uganda, the government has ratified international treaties related to the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women, which covers gender-based violence, but has not passed a domestic bill addressing intimate partner violence. The government’s National Policy for Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) was launched in February 2005 to minimise the effects of internal displacement.Citation4 The IDP policy does not, however, specifically address gender-based violence. The government has been criticised for not enacting national legislation giving women equal rights in marriage and equal protection under the law.Citation5 Moreover, abortion is legal in Uganda only when performed to save the woman’s life; rape alone does not entitle a woman to safe termination of pregnancy.Citation6

The aims of this qualitative study in the Gulu district of northern Uganda were to examine the status of health services available for the survivors of gender-based violence, assess available gender-based violence programmes, and identify the gaps and challenges in provision of services for survivors, using the IASC guidelines as an analytical framework.

IDP camps in northern Uganda

The study was conducted in the Gulu district, northern Uganda, in July 2006. Gulu is one of the most affected districts in the 20-year conflict between the government of Uganda and the rebels of the Lord’s Resistance Army. The conflict has been described as one of the worst humanitarian crises in the world, with the civilian population experiencing intimidation, torture, harassment, killings, abductions and huge numbers of IDPs.Citation7 In June 2006, approximately 1.7 million people in northern Uganda lived in IDP camps. Of these, nearly half a million lived in 48 camps in the Gulu district, which were established primarily as part of the government’s counter-insurgency campaign. They are congested and lack proper sanitation, and rates of mortality, morbidity and mental distress are high.Citation8–11 The camps range in size from around 1,000 people to over 50,000, and while they look like enormous villages, they have many of the social problems associated with urban areas. The IDP population is young; more than 50% are under the age of 15. As many as 25% of the children have lost one or both their parents, and the proportion of widowed women is also high.Citation12

The conflict has greatly disrupted the health system in Gulu district. Health services in the district are provided by a network of public sector, private sector and non-governmental organisations, as well as informal practitioners and traditional healers. The district has five hospitals, 41 government health centres and several private clinics. Approximately only 60% of the government’s health units in Gulu are filled by appropriate health staff, and less than 30% of the population in northern Uganda live within a 5 km radius of a functional health unit.Citation13 There are a few studies with some insight into the nature of gender-based violence and status of programmes to address the problem in some camps in the Gulu district.Citation14Citation15 A study by CARE International in four IDP camps found that different forms of gender-based violence were rampant. Nevertheless, not much had been done to address the problem by the humanitarian agencies and local organisations working in the district.Citation14 A study commissioned by the Gulu District Sub-Committee on Sexual and Gender-Based Violence Group on the nature of gender-based violence in one camp found that “organized care services were not only missing but even sensitization and mobilization of people appeared to be at rudimentary level”. Medical services (treatment of STIs, counselling and first aid) could not be always provided for survivors due to lack of personnel and medical supplies.Citation15

In 2006 the security situation improved, and the Ugandan government and Lord’s Resistance Army agreed a ceasefire in August 2006. However, there has been no large-scale return of IDPs to their homes in the most affected districts of Gulu, Adjumani and Kitgum yet.

To capture the response to gender-based violence at the primary health care level, we visited four government health centres located in four camps and one private clinic located in Gulu town. The IDP camps were located between 15 and 60 km from Gulu town, including Pabbo (population 55,889), Anaka (25,384), Koch Ongako (18,227) and Koch Goma (11,359). These camps were selected because some gender-based violence activities had been initiated there, and because they represented a cross-section of different camp sizes. We purposely selected three hospitals: one public referral hospital in Gulu town, one private, non-profit missionary hospital located 6 km from the town, and one public rural district hospital located 60 km west of Gulu town. We excluded the military hospital and a small private, for-profit hospital located in Gulu town, because camp populations have limited access to them.

Primary data were collected through 26 semi-structured interviews and a review of supplies required for treating survivors of gender-based violence. Of the 26, 23 represented the main actors involved in gender-based violence programming and service provision in Gulu and three who were based in Kampala. Fifteen of the 26 were experts who were actively involved in gender-based violence programming or coordination in Uganda. The rest included four governmental officers, four staff members of local NGOs, three staff members of international NGOs, three UN staff members and one researcher from a Ugandan university. The interviews included questions about each organisation’s current gender-based violence activities and their coordination, training of health personnel, financial resources available, referral mechanisms in place, accessibility of health services to survivors and their perceptions of the nature of gender-based violence.

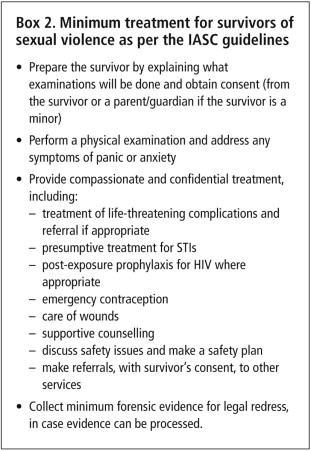

The other 11 people interviewed included three nurses, two midwives and six doctors from the health facilities mentioned above. We used Sections 8.1 (Ensure women’s access to basic health services) and 8.2 (Provide sexual violence-related health services) of the IASC guidelines and key actions recommended in these sections (Box 2) to develop the interview guide for health personnel. We asked questions about training of health personnel, available human resources, coordination of activities with other sectors, accessibility and use of health services with regard to gender-based violence. The interviews were complemented by a review of the availability of medical supplies required for treating survivors, using a checklist based on IASC guidelines.Citation1

One of the authors (MH) conducted the interviews in English. A translator was present to ensure that the local language could be used when necessary. The translator was informed about the research objectives and trained on confidentiality and sensitivity related to gender-based violence. All interviews were transcribed, and the data analysed using thematic analysis based on the interview guide and the IASC guidelines listed in Box 2. Informed, written consent was obtained from all interviewees, and all interviews were kept confidential and anonymous. Ethical approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and Uganda National Council for Science & Technology.

Findings

Concerted efforts within the health sector to address gender-based violence have been undertaken only recently, and there were still considerable gaps. The Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development was finalising a national strategy on gender-based violence. However, a governmental expert and a UN staff member both said that the government did not have the capacity or the financial or human resources to implement gender-based violence interventions. Three NGO representatives also expressed concern about the lack of financial resources available for gender-based violence programmes and the lack of appropriate services.

A gender-based violence Coordination Committee was also in place, chaired by the local government and supported by the UN and international NGOs. In addition to being a forum for sharing information, identifying problems and resolving them, the Committee had designed, but not yet implemented, a district referral system encompassing the police, the legal services and the medical and psycho-social service providers. A number of prevention and care activities in Gulu district had also recently been launched, such as psychosocial support and legal aid, but health personnel were still unaware that these support services existed outside the health sector. One expert reported that sensitisation activities had reached a few IDP camps only.

Of the eight health facilities we visited, only one facility used a protocol for treating survivors of sexual violence that had been developed for internal use. However, the district was in the process of drafting a protocol on the management of rape in line with World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines.Citation16 One doctor stressed the importance of implementing the protocol at the health centre level as the first entry point, to facilitate a timely response. This would also, according to two health workers, increase the accessibility of the services for gender-based violence survivors. Whereas any qualified health worker is allowed to examine and treat survivors of sexual violence, only doctors or medical officers are supposed to complete the legal medical examination forms for possible legal redress. Therefore, survivors have to travel to Gulu town to receive both care and certificates. One government expert believed that some doctors were reluctant to provide medical certificates for fear of having to testify in court. The Coordination Committee were discussing the possibility of enabling clinical officers to fill in the medical examination forms at health centres to improve accessibility. Equipment to collect forensic evidence was available only in the hospitals and the private clinic visited, however.

Seven of the eight health facilities had at least one staff member who had received gender-based violence training from an international organisation. The majority of health workers believed that the training had increased the health sector’s capacity to identify cases of sexual violence, but it had not provided them with sufficient confidence or skills to treat and counsel survivors. One doctor said that the training had merely sensitised personnel. Health personnel and experts suggested that the training should be extended to cover wider cadres of health workers. Furthermore, one doctor and one local expert stressed that gender-based violence should be integrated into existing training modules in order to avoid burdening the health staff with extra training. According to the latter:

“We have 240 guidelines… you imagine this health worker whom we expect to read 240 guidelines and implement them…Maybe we can train them as part of continuing medical education. If you give them a booklet [only], it may end up in the shelf.”

Certain medical supplies were not available in sufficient quantity at the health centres. All three hospitals, but only one health centre, provided emergency contraception. The problem of unwanted pregnancies was reflected in the reported high number of complications resulting from unsafe abortions, particularly among adolescent girls. One hospital reported treating two such cases every day, and one doctor believed that there were many more cases, as many girls in this situation attend private practitioners. At the time of the visit, drugs for treatment of STIs were available in all but one health facility.

The provision of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) as a standard measure to prevent HIV infection of rape survivors is recommended by WHO in high HIV prevalence countries if the HIV status of the assailant is unknown.Citation16 The provision of PEP in this district appeared to be limited, despite a UNHCR evaluation demonstrating the feasibility of providing PEP among displaced populations.Citation17 At the time of the study, PEP kits for HIV were provided in two hospitals and one health centre only. In those facilities that did provide PEP following rape, informants reported that survivors rarely reached them early enough to be able to utilise PEP or emergency contraception. One doctor from a health facility that did not have PEP kits expressed concern about the lack of information as to where PEP kits were available in case they needed to refer a patient. The health personnel also expressed concern that when PEP was provided, patients did not necessarily attend the follow-up visits. This was considered a serious problem, as side effects related to PEP drugs are common. They suggested that survivors who had received initial prophylaxis in a hospital could be referred for follow-up visits to health centres near their communities to increase the frequency of follow-up care. One doctor said that family members and communities should also be sensitised to the purpose and benefits of PEP. One local expert noted that HIV voluntary counselling and testing centres were usually far away from IDP camps.

Although the IASC guidelines stress the need to ensure the confidentiality of health records, we found that health services lacked facilities to keep records locked so the confidentiality of patient records was not assured. The need for informed consent of the survivors was also not met in health centres, as consent forms were available only in one health centre.

In addition, one nurse and one local expert pointed out that it would be essential to establish youth-friendly services with special hours and a more private environment where young people would feel more comfortable about accessing the services without having to mix with adults. However, only one health centre offered weekly youth-friendly services, initiated by a female nurse, in a separate “nurse quarter”.

When asked about the utilisation of services by survivors, all health facilities reported that they had seen only a few cases of sexual violence during the last six months. Health personnel and experts acknowledged that cases may be under-reported due to stigma and shame, and that survivors may seek treatment from private providers and traditional healers, for example, as they do for induced abortion.

Both health personnel and experts felt that rape by strangers, e.g. by combatants, was currently not a frequent event, while sexual abuse of girls aged under 18 (referred to as “defilement” by our interviewees), sexual harassment, intimate partner violence and early or forced marriage were felt to be frequent in northern Uganda. Health personnel and experts considered sexual abuse of girls under 18 years of age, regardless of whether sex was consensual and irrespective of the male’s age, to be a significant problem. Schoolgirls were reported to be frequently targets of sexual harassment. A few of the health personnel and the experts pointed out that intimate partner violence was also common, and generally considered to be a private issue, embedded in the culture.

A few respondents suggested that intimate partner violence had increased due to the harsh living conditions in the camps and alcohol abuse. Many respondents mentioned that early or forced marriage was a common practice for economic survival and security. As one expert put it: “When a girl starts developing breasts, she is said to be ready for marriage” and cohabitation without legal marriage is considered culturally acceptable in northern Uganda. Several respondents pointed out that early marriage was used to cope with shame and stigma following sexual abuse, but that early marriage increased the risk of intimate partner violence. Girls with mental disabilities were deemed to be the most vulnerable group by some respondents. One local expert felt that incest had increased. In general, the respondents’ comments referred to women and girls as survivors, but one local expert noted that men and particularly boys had been victims of gender-based violence, too, especially of sexual violence.

Discussion

This study has a number of limitations. Due to resource constraints, we covered a limited number of camps and their health centres in the Gulu district. However, we did cover three of the five hospitals where those who seek treatment following rape are normally referred. The study focused on formal health services and did not capture medical care that may have been provided by community health workers or informal health care providers. We did not interview survivors of gender-based violence, so we cannot comment on their experience of accessing services, their coping strategies or the community structures to which they may turn for support. In the absence of reliable data on the incidence of rape and other forms of gender-based violence in Gulu, we also cannot assess the degree to which the survivors of rape and other forms of violence require or access services. Despite these limitations, however, we believe some important conclusions can be drawn and recommendations made, both as regards what the health services are able to offer and what should be done at community level.

We agree with our interviewees who recommended that health services for survivors should be increased, especially at the health centre level. However, existing health workers had limited ability to identify and manage gender-based violence cases, and did not feel confident to deal with gender-based violence cases, in spite of training. We suggest that more comprehensive training is needed, and that the number of health personnel equipped to identify and respond to cases of gender-based violence should also be increased. Such training should be integrated into existing reproductive health training modules, to ensure that services for survivors are seen as part of comprehensive sexual and reproductive health services.Citation18 This includes youth-friendly services for the high proportion of young people in the IDP camps among whom a high vulnerability to sexual abuse was reported.

The hospital and health centre personnel should comply with the protocol on the management of rape, and necessary medical drugs including emergency contraceptive pills, drugs for treatment of STIs and post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV should be made widely available in the district in all hospitals and health centres.

Given that women who do seek services do not arrive in time for emergency contraception to be effective to prevent unwanted pregnancy following rape, the illegality of abortion requires serious attention. It is regrettable that the IASC guidelines fail to address the need to provide safe abortion as part of a comprehensive rights-based package of care for women after rape, as noted by Jewkes.Citation18

Previous studies on Uganda indicate that women and girls have been the main victims of various forms of gender-based violence, but acknowledge that men and boys have also been subjected to sexual exploitation and rape.Citation5,10,15 We recommend investigating this issue further,

Pregnant women receive Mama Bags, a kit with essential items for safe delivery from Uganda Red Cross, Adwari IDP camp, Uganda, 2007

As Vann notes: “Without the participation of the community, there will be no incident reports, no clients, no comprehensive response, and only limited prevention.”Citation19 Our health worker respondents were not aware of any support services for survivors in the communities. The need for sensitisation activities by community members with the support of NGOs and the local government among wider sections of the population on this critical problem, particularly among young people, was noted also by a recent assessment by CARE International.Citation14

The Ugandan government has ratified a number of international treaties related to gender-based violence, and the Ministry of Health has recognised the need for special care for survivors. However, this has yet to be translated into adequate services in northern Uganda. NGO respondents commented that financial constraints hampered the implementation of gender-based violence programmes. This reflects a broader issue of weak humanitarian financing for health, with health programmes receiving less than a quarter of the requested funds of the UN Inter-Agency Consolidated Appeal Process.Citation20

A comprehensive response requires the health sector to collaborate with other sectors to prevent gender-based violence by addressing its causes and contributing factors, to educate health staff about the legal aspects of gender-based violence and to ensure legal redress, and to provide psychosocial support for survivors.Citation19Citation21 Establishing the gender-based violence Coordination Committee was an important step towards such inter-sectoral collaboration.

Despite all efforts, the overall access to health care for survivors continues to remain inadequate, mainly due to the lack of technical and operational capacity of the humanitarian actors and the local government, as well as serious procedural obstacles such as filling the legal medical examination form. However, survivors have enhanced access to services (health, legal, protection and psychosocial) in northern Uganda. At the end of 2007, 45% of the sub-counties in northern Uganda had service delivery systems for survivors as compared to 10–15% of the sub-counties in November 2006. Availability of information on the services has resulted in increased number of survivors seeking care.Citation22 This is a significant outcome considering the stigma related to gender-based violence. Nevertheless, the confidence of survivors could be easily lost, if their expectations about the services cannot be met due to insufficient geographical coverage or poor quality of services.

Our respondents were under the impression that rape by strangers was an infrequent event in the Gulu district at the time of the study. This impression may result to some extent from under-reporting,Citation23 and must be interpreted with care. In contrast, respondents claimed that intimate partner violence, sexual abuse of girls and forced and early marriage were very common, which is in line with other studies from northern Uganda.Citation14,24,25 Indeed, a small study found the prevalence of intimate partner violence to be as high as 80% in some conflict-affected areas of Uganda.Citation25 However, Ugandan law does not recognise marital rape as a crime.

Respondents’ suggestion that early marriage and cohabitation increased the risk of intimate partner violence is in line with studies from other countries.Citation24,26,27 Our findings that adolescent girls may be particularly exposed to various forms of gender-based violence is reflected in another study in Pabbo IDP camp in Gulu district, which found that girls aged 13–17 were the most frequently reported as having experienced sexual violence.Citation15

The IASC Guidelines currently focus on sexual violence by strangers in acute emergencies.Citation1 This conception of gender-based violence has greatly influenced the humanitarian action plan for northern Uganda,Citation28 and may be causing the exclusion of girls and women affected by gender-based violence that is not directly conflict-related from prevention and care services. Ward and Vann point out that “although establishing services for rape survivors is critical, rape is just one component of gender-based violence programming”.Citation29 Research is needed on the relative contribution of different types of gender-based violence in northern Uganda, with a view to determining whether a broader concept of gender-based violence should be incorporated into the IASC Guidelines, including guidance on how to respond to other forms of gender-based violence than sexual violence by strangers.

Gender-based violence is a fundamental abuse of women’s rights and has serious consequences for women, their families, and the recovery and development of their communities. National governments have the ultimate responsibility to protect their citizens, to enact and enforce legislation and make resources and services available to address the causes, contributing factors and consequences of gender-based violence. The peace process in northern Uganda provides an opportunity to address gender-based violence in a sustained way; concrete plans about preventing and responding to the problem should be included in peace negotiations and reconstruction efforts.

In resource-constrained and conflict-affected settings, the international community also has an important role to play, by providing financial and technical support for gender-based violence prevention and response services. It is crucial to gather more evidence on the effectiveness and sustainability of gender-based violence programmes, on ways to integrate gender-based violence services into general sexual and reproductive health programmes, and better ways to reach and protect adolescents and young people.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank UNFPA and the Mental Health Department of Gulu Regional Hospital for facilitating the research, and the interviewees for participating in the study. This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust [073109/Z/03/Z].

References

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC). Guidelines for Gender-based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Settings. 2005. At: <www.humanitarianinfo.org/iasc/content/products/. >. Accessed 21 March 2006.

- S Bott, A Morrison, M Ellsberg. Preventing and responding to gender-based violence in middle and low-income countries: a global review and analysis. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper. 2005. At: <www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/main?pagePK=64193027&piPK=64187937&theSitePK=523679&menuPK=64187510&searchMenuPK=64187511&siteName=WDS&entityID=000112742_20050628084339. >. Accessed 23 August 2006.

- Inter-Agency Working Group. Inter-agency global evaluation of reproductive health for refugees and internally displaced persons. 2004. At: <www.rhrc.org/resources/iawg/. >. Accessed 21 March 2006.

- Brookings Institution. Workshop on the implementation of Uganda’s National Policy for Internally Displaced Persons. 2006. At: <www.brookings.edu/fp/projects/idp/conferences/Uganda_Workshop2006_rpt.pdf. >. Accessed 14 August 2006.

- Human Rights Watch. Just Die Quietly. Domestic Violence and Women’s Vulnerability to HIV in Uganda. 2003. At: <www.hrw.org/reports/2003/uganda0803/. >. Accessed 21 March 2006.

- FH Ahmed, E Prada, A Bankole. Reducing unintended pregnancy and unsafe abortion in Uganda. Alan Guttmacher Institute. 2005. At: <www.guttmacher.org/pubs/rib/2005/03/08/rib1-05.pdf. >. Accessed 8 August 2006.

- International Crisis Group. Northern Uganda: Understanding and Solving the Conflict. 2004. At: <www.crisisgroup.org/home/index.cfm?l=1&id=2588. >. Accessed 4 April 2006.

- P Vinck, PN Pham, E Stover. Exposure to war crimes and implications for peace building in northern Uganda. JAMA. 298(5): 2007; 543–554.

- MoH/WHO/UNICEF/IRC. Health and mortality survey among internally displaced persons in Gulu, Kitgum and Pader districts, northern Uganda. At: <www.who.int/hac/crises/uga/sitreps/Ugandamortsurvey.pdf. >. Accessed 25 September 2007.

- Human Rights Watch. Uprooted and Forgotten. Impunity and Human Rights Abuses in Northern Uganda. 2005. At: <http://hrw.org/reports/2005/uganda0905/. >. Accessed 4 April 2006.

- D Paul. Fulfilling the Forgotten Promise: The Protection of Civilians in Northern Uganda. 2006. At: <www.internal-displacement.org/. >. Accessed 4 April 2006.

- Office of the Prime Minister. Northern Uganda Internally Displaced Persons Profiling Study. At: <www.fafo.no/ais/africa/uganda/IDP_uganda_2005.pdf. >.

- Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Consolidated Appeal for Uganda 2006. 2005. At: <www.reliefweb.int/rw/rwb.nsf/db900SID/LSGZ-6J9EFT?OpenDocument&rc=1&emid=ACOS-635PRQ. >. Accessed 4 May 2006.

- Mugisha MA. Report of a Rapid Assessment of Sexual and Gender-Based Violence (SGVB) in Internally Displaced People’s Camps (IDPs) in Gulu District. CARE International, Kampala. 2006.

- CO Akumu, I Amony, G Otim. Suffering in Silence: A Study of Sexual and Gender Based Violence (SGBVGBV) in Pabbo Camp, Gulu District, Northern Uganda. 2005. At: <www.unicef.org/media/files/SGBVGBV.pdf. >. Accessed 21 March 2006.

- World Health Organization. Clinical Management of Rape Survivors, Developing protocols for use with refugees and internally displaced persons. 2004. At: <www.who.int/reproductive-health/publications/clinical_mngt_survivors_of_rape/. >. Accessed 21 March 2006.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Evaluation of the introduction of post exposure prophylaxis in the clinical management of rape survivors in Kibondo Refugee Camps. A field experience. 2005. At: <http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2005/pep_field_experience.pdf. >. Accessed 25 September 2007.

- R Jewkes. Comprehensive response to rape needed in conflict settings. Lancet. 369: 2007; 2140.

- B Vann. Gender-Based Violence: Emerging Issues in Programs Serving Displaced Populations. 2002. At: <www.rhrc.org/pdf/gbv_vann.pdf. >. Accessed 21 March 2006.

- A Pinel, LK Bosire. Traumatic fistula: the case for reparations. Forced Migration Review. 27: 2007; 18–19. At: <www.fmreview.org/mags1.htm. >. Accessed 20 August 2007.

- A Guedes. Addressing gender-based violence from the reproductive health/HIV sector: a literature review and analysis. 2004. At: <www.eldis.org/static/DOC15767.htm. >. Accessed 24 April 2006.

- Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Consolidated Appeal for Uganda 2008. 2007. At: <http://ochaonline.un.org/humanitarianappeal/webpage.asp?Page=1632. >. Accessed 31 January 2008.

- L Shanks, N Ford, M Schull. Responding to rape. Lancet. 357: 2001; 304.

- N Gottschalk. Uganda: early marriage as a form of sexual violence. Forced Migration Review. 27: 2007; 53. At: <www.fmreview.org/mags1.htm. >. Accessed 20 August 2007.

- Uganda Law Reform Commission. A study report on domestic violence. Kampala. 2006.

- M Hynes, K Robertson, J Ward. A determination of the prevalence of gender-based violence among conflict-affected populations in East Timor. Disasters. 28(3): 2004; 294–321.

- World Health Organization. WHO Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women. Summary Report. 2005. At: <www.who.int/gender/violence/who_multicountry_study/summary_report/en/index.html. >. Accessed June 30 2006.

- Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Consolidated Appeal for Uganda 2007. At: <http://ochaonline.un.org/cap2005/webpage.asp?Page=1498. >. Accessed 8 August 2007.

- J Ward, B Vann. Gender-based violence in refugee settings. Lancet. 360(Suppl): 2002; s13–s14.