Abstract

In April and May 2006, internal conflict in Timor-Leste led to the displacement of approximately 150,000 people, around 15% of the population. The violence was most intense in Dili, the capital, where many residents were displaced into camps in the city or to the districts. Research utilising in-depth qualitative interviews, service statistics and document review was conducted from September 2006 to February 2007 to assess the health sector’s response to reproductive health needs during the crisis. The study revealed an emphasis on antenatal care and a maternity waiting camp for pregnant women, but the relative neglect of other areas of reproductive health. There remains a need for improved coordination, increased dialogue and advocacy around sensitive reproductive health issues as well as greater participation of the health sector in response to gender-based violence. Strengthening neglected areas and including all components of sexual and reproductive health in coordination structures will provide a stronger foundation through which to respond to any future crises in Timor-Leste.

Résumé

En avril et mai 2006, le conflit interne au Timor-Leste a déplacé près de 150 000 personnes, environ 15% de la population. La violence était particulièrement intense à Dili, la capitale, où beaucoup d’habitants ont été placés dans des camps en ville ou dans des districts. Une recherche utilisant des entretiens qualitatifs approfondis, les statistiques des services et une étude de documents, menée de septembre 2006 à février 2007, a évalué la réponse du secteur de la santé aux besoins de santé génésique pendant la crise. L’étude a révélé une priorité aux soins prénatals et à un camp où les femmes enceintes attendaient leur accouchement, mais une relative inattention à d’autres domaines de la santé génésique. Il faut améliorer la coordination, accroître le dialogue et le plaidoyer autour de questions sensibles de santé génésique tout en relevant la participation du secteur de la santé en réaction à la violence sexiste. Le renforcement des domaines négligés et l’inclusion de toutes les composantes de la santé génésique dans les structures de coordination constitueront un fondement plus solide à partir duquel répondre à toute crise future au Timor-Leste.

Resumen

En abril y mayo de 2006, el conflicto interno en Timor-Leste llevó al desplazamiento de aproximadamente 150,000 personas, un 15% de la población. La violencia fue más intensa en Dili, la capital, donde muchos residentes fueron desplazados a campamentos en la ciudad o a los distritos. Desde septiembre de 2006 hasta febrero de 2007, se realizaron investigaciones con entrevistas cualitativas a profundidad, estadísticas de servicios y revisión de documentos, a fin de evaluar la respuesta del sector salud a las necesidades de salud reproductiva durante la crisis. El estudio reveló énfasis en la atención antenatal y un campo maternidad de espera para las mujeres embarazadas, pero el relativo descuido de otras áreas en salud reproductiva. Aún existe la necesidad de mejorar la coordinación y ampliar el diálogo y las actividades de promoción y defensa en torno a los aspectos delicados de la salud reproductiva, así como incrementar la participación del sector salud en respuesta a la violencia basada en género. Al fortalecer las áreas desatendidas e incluir todos los elementos de la salud sexual y reproductiva en las estructuras de coordinación, se creará una base más sólida a partir de la cual se pueda responder a toda crisis futura en Timor-Leste.

Complex emergencies intensify many reproductive health risks. They decrease access to health facilities and emergency obstetric care, and often exacerbate the risk of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). They may increase risks of gender-based violence due to disrupted family and community life, disturbance of social norms, risks of coercion and abuse in exchange for food, income, shelter or protection, and a breakdown of law and order.

In response to growing international concern, reproductive health and human rights have attracted attention and led to the formation of the Reproductive Health Response in Conflict Consortium and the Inter-Agency Working Group on Reproductive Health in Crisis Settings, which, with their affiliated organisations, have been especially influential. Manuals and guidelines have been developed to help governments and humanitarian agencies better respond;Citation1–4 the Minimum Initial Services Package (MISP) is the most structured effort to promote comprehensive planning and delivery of reproductive health services in the early phase of a crisis.Citation5

Timor-Leste (East Timor) is one of the world’s youngest countries. It gained independence in 2002 after 400 years of Portuguese colonisation, 25 years of Indonesian occupation and a brief but intense civil conflict which followed the referendum on independence in 1999. The population of approximately one million people live primarily in rural areas, with Dili, the capital city, being home to just over 15% of the population.

Timor-Leste, like other fragile states emerging from major periods of conflict, faces significant challenges in creating a climate of safety and security in which development can proceed.Citation6 The recurrence of violence is common in many “post”-conflict nations,Citation7 and tensions erupted in April 2006 in Dili, accompanied by a collapse of law and order and the destruction of over 3,000 homes. During the height of the crisis in June 2006 there were approximately 70,000 internally displaced people (IDPs) living in make-shift camps across the city and a further 75,000 displaced to rural districts.Citation8 In April 2008, there were still tens of thousands of people living in IDP camps in the country.

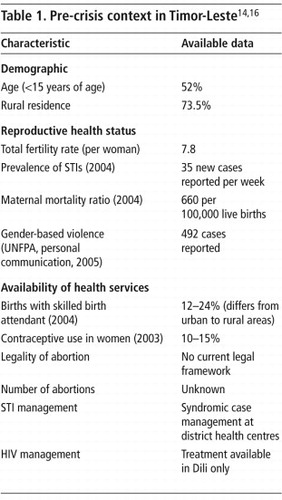

Busza and LushCitation9 suggest a framework for planning reproductive health interventions in crises; this builds on an appreciation of the pre-existing context, the nature of the displacement and conflict, and possible health outcomes. Baseline data from Timor-Leste (Table 1) reveal a young, mainly conservative Catholic population with high fertility, high maternal mortality and widespread gender-based violence. Culture and tradition remain important influences on the decision to seek care during pregnancy, birth and post-partum, and there is a low level of skilled attendance at births, with most women delivering at home. Access to care is further limited by poor road conditions, a dispersed rural population and low levels of income and employment.

Table 1 Pre-crisis context in Timor-Leste, most recent dataCitation14Citation16

The health system in Timor-Leste is still relatively young and Safe Motherhood has been a priority for the Ministry of Health since it was established in 2002.Citation10 In 2004, a comprehensive Reproductive Health Strategy was developed,Citation11 maintaining a focus on Safe Motherhood. While other components such as STI, HIV/AIDS, family planning and adolescent health are gradually being phased in, providing the full range of reproductive health services remains a significant challenge due to the lack of infrastructure, incomplete supply of health commodities and limited capacity of the health workforce.

The 2006 crisis resulted in another cycle of forced migration, for health workers and managers as well as the general population. There was a breakdown of social structures as real or perceived tensions between Loromonu (Westerners) and Lorosae (Easterners) took hold. Access to health services was reduced across the country due to lack of mobility and security fears.

This research aimed to assess the response to reproductive health needs during and after the most acute period of the crisis in April and May 2006 and the subsequent six months. This paper highlights the difficulties in implementing specific components of the reproductive health services package among IDPs and discusses the implications for future planning for reproductive health services in crisis situations in Timor-Leste.

Methods

This research was conducted by a multi-institutional and multi-disciplinary team, including Australian and Timorese researchers and Timorese research assistants, led by the University of New South Wales, with the support of the former Minister for Health, Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste. It was an important component of the Timor-Leste Health Sector Resilience Study.Citation12 Ethics approval was obtained from the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC 06249) and the Ministry of Health in Timor-Leste.

Multiple data collection methods were used, including in-depth interviews, informal discussion, observation, document review and analysis of available quantitative data. The documents reviewed included minutes of coordination meetings, routine data from public and private health services, press releases and situation reports. Routine statistics relating to reproductive health services in Dili and the district health centre in each of the study districts were collected, including number of births, mobile clinic activities, and number of contraceptives distributed. Quantitative data were obtained from the National Hospital, the Ministry of Health’s central information system, district health centres, UN agencies, NGOs and non-government health providers. Due to the crisis, problems with routine data collection were exacerbated and thus only verifiable quantitative data are presented here.

Key informants were identified through snowball sampling. Selection criteria included knowledge of at least one component of reproductive health, presence in the country during the emergency phase of the crisis, and working in the area of health policy, service delivery or research in Timor-Leste. Thirty-five semi-structured, in-depth interviews and five focus group discussions, supplemented with informal discussions, were conducted in Dili as well as in four rural districts from September 2006 to February 2007. Interviews were recorded in notes and/or tape-recorded after verbal or signed consent was obtained. Interviews were conducted in either English or Tetum, depending on the preference of the respondent and with the assistance of an interpreter as required. Informal discussions were recorded in a notebook either during the discussion or later the same day, and were included in data analysis. All interview notes, transcripts and discussion notes were imported into the software package NVivo7, and coded for a range of reproductive health issues identified through the literature, as well as for additional themes that emerged during the data collection and analysis.

Findings

Coordination and priority setting

During the emergency phase of the crisis, the Ministry of Health’s main priorities were to maintain service delivery and reassure the community that health care needs would be addressed.Citation12 A manager from the Ministry of Health said, “Our annual action plan was disrupted. We have four areas: Safe Motherhood, Family Planning, Reproductive Health for Adolescents, and Comprehensive Reproductive Health. During the crisis we focused on Safe Motherhood and Family Planning.” Alongside delivering health care to IDPs in the camps, the Ministry of Health gave priority to keeping three key services operating in Dili: the National Hospital, the ambulance system and the drug distribution system. The Cuban Medical Brigade, who were providing services in Dili and the districts, were mobilised, with extra staff being drawn in to provide mobile services and 24-hour health posts within the IDP camps.

Coordination between the Timor-Leste government, the Ministry of Health, local development organisations and incoming humanitarian agencies worked well because of the long-standing relationships between the government and development partners and the leadership of the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Labour and Community Reinsertion.Citation12 Within weeks of the initial conflict in April, a maternal and child health (MCH) working group was formed within the larger humanitarian coordination structure. Although there was an awareness of the national reproductive health policy framework, priority was specifically given to Safe Motherhood and family planning within the MCH coordination meetings. An MCH assessment conducted in the districts in July 2006 found that although they encountered some problems with equipment and the supply of contraceptives, MCH services were still functioning.Citation13 Thus, the reproductive health response to the crisis focussed on the safety of pregnant women in Dili and proceeded with two main strategies: providing mobile antenatal care to the IDP camps and establishing a maternity waiting camp at the National Hospital.

Antenatal care

Initially general health services to the camps were provided by the Cuban Medical Brigade, but there was some concern that these mobile clinics did not have the basic equipment and supplies for comprehensive antenatal care. Additional services tailored specifically to pregnant women were subsequently added as part of the coordinated response. However, a programme coordinator from a UN Agency stated, “[The Cuban Medical Brigade] weren’t equipped to provide appropriate antenatal care services according to the standard. Not all of them could measure the fundus, they didn’t have a [fetal] stethoscope, no way of measuring fetal heart beat during the consultation. They didn’t have immunisation, tetanus toxoid for example, and they didn’t have mosquito nets. Having antenatal and post-natal care through mobile clinics established in Dili ensured… antenatal care services were provided at a higher level during the emergency time.” And one respondent who was at a Water and Sanitation meeting stated: “It is clearly counter-productive for capacity building and national morale to have basic services provided long-term by groups other than the government and public sector.” (Water and Sanitation Coordination Meeting, 5 January 2007).

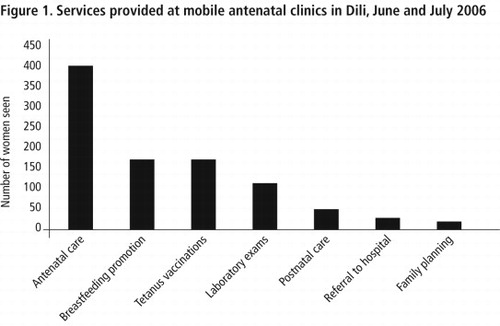

These mobile antenatal care services were provided by a small team of local and expatriate obstetricians, doctors and midwives to 29 of the 56 camps, and were conducted over two cycles from 6–26 June and 3–27 July 2006. A range of services were provided to women of reproductive age, but the main focus was on antenatal care (). The clinics ceased after two months because the Ministry of Health sought to promote a sense of normality by encouraging community members to access care through the health centres in Dili.

Maternity waiting camp

Prior to the crisis the majority of births in health facilities in Dili took place at the National Hospital. During the crisis access to birthing services and emergency obstetric care at the National Hospital was limited, especially at night, as mobility was hampered; the ambulance service was unable to attend certain areas; and the hospital itself had become a large IDP camp with concerns about safety both within and around it.Citation12

In response to reports that some women had given birth in the IDP camps without privacy, a maternity waiting camp, comprising two dozen tents, was set up on the grounds of the National Hospital in early June 2006. The objective was to improve access for hospital-based births and emergency obstetric care. Pregnant women, sometimes accompanied by their families, were identified and encouraged to stay at the maternity waiting camp while they awaited the birth of their child at the adjoining hospital. After they had been registered and transported to the maternity waiting camp by a local NGO, Rede Feto, pregnant women received additional food and other essential items and were exposed to relevant perinatal health promotion messages.

By 30 November 2006, 261 pregnant women had been transferred to the maternity waiting camp. Once women and their families became stationed at the hospital and had given birth, however, it proved difficult to get them to leave to make way for others. By February 2007 there were no pregnant women staying at the maternity waiting camp, but 49 post-partum women and their families were occupying the tents (Timor-Leste Humanitarian Update, 21 February 2007).

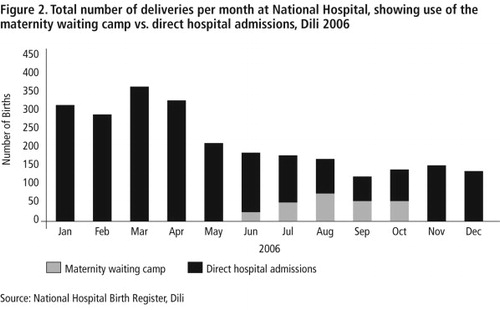

Despite the effort made to increase access to hospital birthing services for displaced women, the number of deliveries at the National Hospital continued to decline even after the maternity waiting camp opened (). The 50% reduction in the number of births at the National Hospital during the crisis probably reflects a combination of the reluctance of women in Dili to attend the hospital due to security fears, the reduced number of pregnant women in Dili and the refusal by some women to be referred to the National Hospital. In contrast, the number of births doubled in the study districts outside Dili and also increased slightly at a non-government clinic in the city.Citation12

The maternity waiting camp accounted for approximately one quarter of the births at the National Hospital in the first five months of operation, but very few thereafter. The maternity waiting camp strategy, therefore, did not provide a sustainable solution for the needs of most women seeking to deliver in a safe health care environment. A major reason for under-utilisation was the lack of perceived safety at the site.

Family planning

The availability of family planning has been relatively recent in newly independent Timor-Leste. Around 15% of women use contraceptives,Citation14 few staff are trained in family planning and commodities are sporadically unavailable. During MCH coordination meetings early in the crisis, family planning was a stated priority, and there was some effort to provide commodities through the mobile antenatal clinics. Despite the relatively supportive stance taken by the Catholic church toward family planning in Timor-Leste, some health providers were reluctant to promote a high profile family planning service, particularly to the many camps that were on church grounds. A programme coordinator from a UN Agency said, “It was a bit difficult with family planning services at the mobile clinics. Not to promote, but to openly offer this kind of service is sensitive, because most camps are located in areas of the church. We didn’t ignore it in the mobile services. They would provide services if the woman asked it but they didn’t deal openly”.

The undeveloped nature of the family planning programme, the low demand for contraceptives and the lack of privacy during mobile clinics, combined with differential access to mobile services, resulted in very few women accessing family planning services in IDP camps. In contrast with the 399 women seen for antenatal care during mobile clinics, only 16 women were provided with family planning services (), possibly related to the perceived social sensitivity around promoting family planning. A director of an international NGO said: “When they did go out for the antenatal care they tried to address family planning needs but I am not sure that it was communicated to the extent that people were aware that the services were available.”

During the crisis, family planning commodities were also supplied through health centres in Dili, and more than 1,000 contraceptives (90% injectables, 10% pills), were provided through health centres in Dili during June and July 2006. Mobile clinics made a negligible contribution to the provision of contraceptives, underscoring the importance of enhancing the availability of family planning and birth spacing services in general.

Sexually transmitted infections and HIV/AIDS

Despite some effort by a local NGO and a UN agency to promote awareness of HIV/AIDS and well developed international guidelines for STI and HIV prevention in emergency situations, these issues were not highlighted as part of the coordinated emergency response in Dili. A manager in the Ministry of Health reported: “During the emergency response we didn’t pay attention to this issue [HIV], we focused our attention on the basic package, for things that are really emergency. We do not consider HIV an emergency thing. We need to focus our attention on diseases that can kill many more people than this one, like dengue and diarrhoea… there are many important things that should be done first.”

There is widespread stigma associated with discussing, using or promoting condoms, as they are seen by some community members and some church representatives as promoting promiscuity. The lack of attention to STI and HIV prevention during the crisis meant that even if condoms were present at health centres in Dili and the districts, they were not extensively distributed by service providers or accepted by patients. There appeared to be an overall decline in the distribution of condoms in Dili in 2006, resulting in a complete absence of reported condom distribution during the crisis. Data from the Ministry of Health’s information system suggest that no STIs were treated in Dili in 2006, with the exception of January.

Gender-based violence

Prior to the crisis in 2006, cases of gender-based violence could be addressed through a vulnerable persons unit within the national police force (PNTL). The collapse of the police force in April 2006 meant that this specialised unit was not functioning. The Protection Working Group established a sub-group to monitor and address gender-based violence in response to the crisis. A key challenge was developing agreed protocols and a reliable referral system among the many actors involved.

From 1 June to 31 October 2006 there had been only 12 cases of domestic violence, child abuse and sexual assault (including three cases of rape) reported through the referral network (UN agency Gender Based Violence Project Manager, Personal communication, 10 September 2007). However, a member of the Protection Working Group commented in January 2007 about ongoing risks: “The women have also expressed concern about the security in the camps, especially at nightfall, when young men are known to visit the tents and unzip them without approval or knowledge of the people residing inside.”

An assessment conducted in the early phase of the crisis reported an increased risk of gender-based violence within IDP camps due to crowded conditions, separation from family, and alcohol and trauma associated with threats of house-burning.Citation15 This was coupled with an increased reluctance to report cases due to the lack of personal security, absence of a police force and tensions between different community groups. The numbers reported are thought to be well below the actual incidence of gender-based violence. Reporting was affected by a range of issues, including difficulties in monitoring and visiting all the camps to collect information, as well as male-dominated systems at some stages.

Training activities for camp managers, gender-based violence focal points, NGOs, the legal sector, UN agencies, UN police and women in IDP camps were considerable. Relatively little attention, however, was focused on men, who did not participate actively in many of the related community meetings and activities. Indeed, within the community, gender issues are often seen as neither the domain of men nor of health workers, but rather of women alone. As a programme officer from a UN agency reported: “It seemed that the immediate health issues were addressed first… I think sexual violence is quite prevalent in this country. I think it is something that has been on the radar, but it certainly wasn’t brought up in the health sector working group.”

Despite the impact that gender-based violence has on the health of women and children, and the importance of involving health workers at all levels in referral networks and treatment and counselling services, there has been little involvement of the health sector in coordination mechanisms, training or outreach in relation to gender-based violence.

Adolescent health

Notwithstanding a very young population, with more than half below the age of 18 years, prior to the crisis there was no comprehensive and organised approach to addressing the health needs of adolescents in the country.Citation16 Internationally, however, this is increasingly recognised as demanding attention.Citation17

The absence of a focus on youth and adolescent health is related to the lack of development in this area prior to the crisis. It was agreed that for the emergency response it was best to avoid short-term projects for undeveloped programmes as there was a limited foundation with which to implement activities.

Discussion

The mass population displacement in Timor-Leste in 2006 was a response to the rapid deterioration in security and resulted in the collapse of many essential government services. The crisis was anticipated as being short-lived, and therefore the health sector prioritised a basic package of front-line, clinical services which included averting epidemics and promoting the safety of pregnant women and children. Although Timor-Leste has a comprehensive reproductive health strategy, the response was implemented within a Safe Motherhood framework, reflecting the most developed aspects of the National Strategy. It under-emphasised other aspects of men’s and women’s health, such as freedom from violence, the right to chose when and how many children to have, and the right to knowledge and access to barrier methods to prevent STI and HIV transmission. It may also have reflected the predominance of development agencies operating during the emergency rather than being led by humanitarian agencies which might have more actively promoted the comprehensive strategies outlined in MISP and SPHERE guidelines. The maternity waiting camp, while an innovative and symbolic response by government, UN and NGOs, was not demonstrably effective in widening the reach of supervised deliveries. The Ministry of Health and hospital management subsequently agreed to avoid introducing a maternity waiting camp and attracting IDP families to the hospital.

Successfully integrating all the components of reproductive health is not easy. In other conflict settings it has proven difficult to merge maternal and child health and family planning with HIV/STI control because the former consist of “simple, cost-effective preventive measures for women and their children” while HIV/STI activities may be more difficult to implement because they involve “other population groups, are sensitive, and have unconfirmed efficacy and costs, especially for women”.Citation18 In Timor-Leste selected aspects of reproductive health services were chosen and adapted to the perceived needs of the population and the existing strengths of various programs, organisations and individuals.

In any emergency response it is crucial to modify guidelines to the local context,Citation19 and the Timorese Ministry of Health and its partners displayed exceptional leadership and flexibility in sustaining the health system through the crisis.Citation12 Nevertheless, a comprehensive reproductive health framework can, and should, be used as a means of drawing attention to important, but often neglected areas. For example, with such a young population and significant levels of social disruption, violence and untreated STIs in high risk groups, the health sector in Timor-Leste could have taken some steps towards accelerating coordination and action in these areas, or encouraging key NGOs within a coordinated approach, to fill gaps that the Ministry was unable to cover.

The more extensive collaboration around gender-based violence during the crisis, and leadership from outside the health sector, illustrates the importance of involving the health sector while recognising the engagement of many other agencies and sectors. Given the patriarchal nature of Timorese society, broader awareness of gender-based violence would be of value, including active engagement of men. Recent programmes in Africa have worked with men and demonstrate improved gender sensitivity and respect,Citation20Citation21 adaptations of which might be considered in Timor-Leste. Sexual health promotion and treatment may be able to operate partly through family planning services and antenatal care provision, but there is little emphasis on understanding what services non-pregnant women and men need or try to access for sexual health either in crises or peace time.

The lack of youth-specific sexual and reproductive health services and information during the crisis may have increased adolescents’ vulnerability to the effects of sexual exploitation, unwanted pregnancies and STIs, and hampered their ability to obtain help for these “socially sensitive” problems. A youth health focus could promote attention to addressing the needs of the growing population of young people, also engaging with young people, both male and female, around their reproductive health needs and concerns, and shaping appropriate service and policy responses.

Nine years ago there was limited evidence from the field of changes in the provision of reproductive health services in emergencies: these findings remain applicable.Citation22 The difficulty in the implementation of a comprehensive reproductive health package may be linked to the vertical nature of programmes where “historically-competing bureaucracies in family planning, maternal and child health, gender and development, and HIV/AIDS are not easily unified as ‘reproductive health’”.Citation23

In Timor-Leste, a cross-agency reproductive health coordinator, as advocated by the MISP, was not appointed, and leadership and advocacy around a more comprehensive response, especially as conditions became more stable, was not evident. The response was organised predominantly under MCH coordination structures and focused on pregnant women. In broader human rights terms, this did not address the needs of women outside of motherhood. A deeper social perspective incorporates women’s voices and experiences of their health, illness and well-being. However the response by the government and NGOs, including the Ministry of Health, needs to extend “beyond improving reproductive function toward advancing the social, economic, and political status of women”.Citation24 This begins with more effort to seek women’s input in policy, planning and decision-making, even in emergencies,Citation25 and providing a range of options appropriate to the needs of women in different, albeit difficult, circumstances.

Conclusion

During the emergency phase of a complex and protracted conflict there may be general agreement between providers and beneficiaries that the focus should be on saving lives.Citation22 This can, however, result in major health problems such as unwanted pregnancies, abortion, STIs, HIV/AIDS and gender-based violence being neglected. Our research shows that in Timor-Leste, as elsewhere,Citation26 there is a large gap between what is recommended and the reality in the field. Neither clear leadership nor coordination across all spheres of reproductive health was apparent. Thus, some areas, weak before the crisis, continued to be neglected. The important step of appointing a reproductive health coordinator to manage the range of services and relationships was not taken. Neither was developing a comprehensive and coordinated reproductive health response.

In order to have a foundation to act, effort should be made to develop those programmes which remain weak. STI/HIV, gender-based violence and unwanted pregnancy require attention within existing health services in Timor-Leste. Dialogue should be increased with community and church leaders regarding improved access to family planning, including condoms, prior to and during crises. Adolescent health requires participatory input and planning to provide appropriate services. Much can be learned from “fragile states” and the ongoing need for preparedness, maintaining supplies, prior training, and clear policies to deal with continuing tensions that may flare up into crisis situations.

Acknowledgements

The Timor-Leste Health Sector Resilience Study was funded by AusAID and supported by the Ministry of Health Timor-Leste. This paper covers the reproductive health component of that study, which was led by Anthony Zwi and Kayli Wayte. Members of the broader study team were Avelino Guterres, Paula Gleeson, Natalie Grove, David Traynor, Derrick Silove and Daniel Tarantola: we acknowledge their assistance. Madelena Guterres and Luis Cardoso helped with fieldwork, interpretation and transcription. The authors gratefully acknowledge the participation of all informants. Hernando Agudelo, Ingrid Bucens and Therese McGinn provided helpful comments on an earlier draft. The findings from this research were presented by KW at the conference Transitions: Health and Mobility in the Asia Pacific, Melbourne, June 2007. KW will use part of this research towards a PhD thesis.

References

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. The Inter-Agency Field Manual on Reproductive Health in Refugee Situations. 1999; UNHCR: Geneva.

- World Health Organization. Reproductive Health during Conflict and Displacement: A Guide for Programme Managers. 2000; WHO: Geneva.

- SPHERE. Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Disaster Response. 2004; SPHERE Project: Geneva.

- Inter Agency Standing Committee. Guidelines for Gender-based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Settings: Focusing on Prevention of and Response to Sexual Violence in Emergencies. 2005; IASC: Geneva.

- Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children. Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP) for Reproductive Health in Crisis Situations: A Distance Learning Module. 2006; WCRWC: New York.

- A Zwi, N Grove. Challenges to human security: reflections on health, fragile states and peacebuilding. A Mellbourn. Health and Conflict Prevention. Anna Lindh Programme on Conflict Prevention. 2006; Gidlunds forlag: Hedemora, 119–139. At: <www.med.unsw.edu.au/SPHCMWeb.nsf/resources/Ana_Lindh.pdf/$file/Ana_Lindh.pdf. >. Accessed 20 March 2008.

- P Collier. The Bottom Billion: Why the Poorest Countries Are Failing and What Can Be Done About It. 2007; Oxford University Press: New York.

- Ministry of Labour and Community Reinsertion. Humanitarian situation report, June 2007. 2007; Timor-Leste Ministry of Labour and Community Reinsertion: Dili.

- J Busza, L Lush. Planning reproductive health in conflict: a conceptual framework. Social Science and Medicine. 49(2): 1999; 155–171.

- Ministry of Health. Timor-Leste National Health Policy Framework. 2002; Ministry of Health: Dili.

- Ministry of Health/UNFPA/WHO. National Reproductive Health Strategy 2004–2015. 2004; Ministry of Health: Dili.

- A Zwi, J Martins, N Grove. Timor-Leste Health Sector Resilience and Performance in Times of Instability. University of New South Wales, Sydney, 2007. At: <www.sphcm.med.unsw.edu.au/SPHCMWeb.nsf/page/Timor-Leste. >. Accessed 20 March 2008.

- Ministry of Health. Maternal and Child Health Services District Assessment, July 2006. 2006; Maternal and Child Health Department, Ministry of Health: Dili.

- Ministry of Health, National Statistics Office, University of Newcastle, et al. Timor-Leste 2003 Demographic and Health Survey. 2003; Ministry of Health: Dili.

- Rede Feto. Results of Initial Gender Based Violence Assessment: IDP Camps, Dili. Dili: Rede Feto, 2006. (Unpublished report)

- WHO. WHO Country Cooperation Strategy 2004–2008. Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste. 2004; WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia: Delhi.

- LH Bearinger, RE Sieving, J Ferguson. Global perspectives on the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents: patterns, prevention and potential. Lancet. 369: 2007; 1220–1231.

- L Lush, J Cleland, G Walt. Integrating reproductive health: myth and ideology. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 77(9): 1999; 771–777.

- N Martins, PM Kelly, JA Grace. Reconstructing tuberculosis services after major conflict: experiences and lessons learned in East Timor. Public Library of Science Medicine. 3(10): 2006; e383.

- C Keeton. Changing men’s behaviour can improve women’s health. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 85(7): 2007; 505–506.

- RK Verma, J Pulerwitz, V Mahendra. Challenging and changing gender attitudes among young men in Mumbai, India. Reproductive Health Matters. 14(28): 2006; 135–143.

- C Palmer, L Lush, A Zwi. The emerging international policy agenda for reproductive health services in conflict settings. Social Science and Medicine. 49(12): 1999; 1689–1703.

- LA Richey. HIV/AIDS in the shadow of reproductive health interventions. Reproductive Health Matters. 11(22): 2003; 30–35.

- C Pavlish. Refugee women’s health: collaborative inquiry with refugee women in Rwanda. Health Care for Women International. 26: 2005; 880–896.

- CA Palmer, AB Zwi. Women, health and humanitarian aid in conflict. Disasters. 22(3): 1998; 236–249.

- UNHCR. Reproductive Health Services for Refugees and Internally Displaced Person: Report of an Inter-Agency Global Evaluation. 2004; UNHCR: Geneva. At: <www.unhcr.org/publ/PUBL/41c9384d2a7.html. >. Accessed 20 March 2008.