Abstract

The development of dilatation and evacuation (D&E) as a method of second trimester surgical abortion occurred soon after abortion law reform took place in the 1960s and 1970s in Europe and the United States. Today, D&E is the predominant method of second trimester abortion in many parts of the world. Debate still exists as to whether surgical or medical methods are optimal for second trimester pregnancy termination. A continuing challenge to provision of D&E is the availability of a large enough pool of skilled providers. This article reviews the current surgical methods used in second trimester abortion, as well as their safety, advantages and disadvantages, acceptability and associated complications. Methods used to ensure safe and efficient surgical termination of second trimester pregnancies such as cervical preparation and ultrasound guidance are also reviewed.

Résumé

La technique de dilatation et d'évacuation (D&E) pour l'avortement du deuxième trimestre s'est développée rapidement après la réforme de la législation sur l'avortement dans les années 60 et 70 en Europe et aux États-Unis. Aujourd'hui, dans certaines régions du monde, c'est la méthode la plus utilisée pour les avortements du deuxième trimestre ; néanmoins, l'avortement médicamenteux est également fréquent. Le débat se poursuit pour déterminer lequel de l'avortement chirurgical ou médicamenteux est le plus indiqué en cas de grossesse du deuxième trimestre. Un obstacle récurrent à la pratique de la méthode par dilatation et évacuation est la disponibilité de soignants qualifiés en nombre suffisant. Cet article passe en revue les méthodes chirurgicales d'avortement actuellement utilisées au deuxième trimestre, ainsi que leur sécurité, leurs avantages et inconvénients, leur acceptabilité et les complications associées. Il examine également les techniques utilisées pour garantir une interruption de grossesse sûre et efficace au deuxième trimestre, comme la préparation du col, les agents pour supprimer le fłtus et le contrôle par ultrasons.

Resumen

El desarrollo de la dilatación y evacuación (D&E) como método de aborto quirúrgico en el segundo trimestre evolucionó rápidamente tras la reforma de la ley de aborto en las décadas de los sesenta y setenta, tanto en Europa como en Estados Unidos. Hoy en día, la D&E es el método predominante de aborto en el segundo trimestre en algunas partes del mundo; sin embargo, el aborto con medicamentos también es común. Aún existe debate respecto a cuál es óptimo para la interrupción del embarazo en el segundo trimestre: el aborto quirúrgico o el aborto con medicamentos. Un reto continuo a la prestación de servicios de D&E es la disponibilidad de suficientes prestadores capacitados. En este artículo se estudian los métodos quirúrgicos utilizados actualmente en los procedimientos de aborto en el segundo trimestre, así como su seguridad, ventajas y desventajas, aceptación y complicaciones asociadas. También se analizan los métodos utilizados para garantizar la interrupción quirúrgica, segura y eficaz del embarazo en el segundo trimestre, como la preparación cervical, los agentes para causar la muerte del feto y la orientación en ecografía.

The first suction apparatus for uterine evacuation was introduced in the United States in 1966 and quickly adopted for use in surgical abortion. In an early cohort study there, 93% of procedures under 12 weeks gestation were performed using this method.Citation1 Surgical abortion in the second trimester was, however, relatively unavailable. As gestation advanced beyond 13 weeks, medical induction accounted for 77% of abortions. At 17 weeks gestation and above, the only surgical options were hysterectomy and hysterotomy, and were rarely performed.

Trans-cervical instrumentation of the second trimester uterus was considered controversial in those early days.Citation2Citation3 However, in the same year that these statistics were published in the US, Bierer and Steiner described the successful use of slowly expanding intra-cervical seaweed tents (laminaria) followed by manual dilatation and forceps evacuation for mid-trimester abortion in the British medical literature.Citation4 This report, along with others by innovative surgeons in Europe and the United States in the ensuing years, led to the development of what is today known as dilatation and evacuation (D&E).Citation5

Safety of D&E

The safety of D&E compared to available methods of medical induction was demonstrated using cohort data collected by the Joint Program for the Study of Abortion under the Population Council and the US Centers for Disease Control (JPSA/CDC) from 1970–78.Citation6Citation7 Induction of labour by intra-amniotic instillation of saline or urea-prostaglandin F2-alpha was shown to have higher relative risks of serious complications than D&E (RR 2.6, 95% CI 1.9–3.6 and RR 1.9, 95% CI 1.2–3.1, respectively). One randomised trial comparing D&E to intra-amniotic instillation of prostaglandin F2-alpha supported these findings.Citation8 Importantly, these studies demonstrated that D&E was a skill that could be rapidly acquired by surgeons familiar with pelvic surgery through focused training and incremental advancement of gestational age thresholds.Citation2 Investigators also showed that D&E could be safely performed on an outpatient basis in non-hospital settings.Citation9–11 With cervical preparation occurring a few hours to 24 hours prior to surgery, the development of D&E made second trimester surgical abortion safer, faster and more cost-effective than the available medical alternative.Citation12

Instillation abortion is uncommon in modern abortion care. Prostaglandin analogues such as misoprostol were found to improve the efficacy and speed of induction abortion with a reduction in side effects.Citation13 The inclusion of the antiprogesterone mifepristone to medical abortion regimens further shortened the induction time, and decreased both the dose of prostaglandin required and the need for analgesia.Citation14–16 Use of these medications has largely replaced instillation techniques.

Few studies compare D&E with current methods of second trimester medical abortion. Autry and colleaguesCitation17 retrospectively assessed complications with D&E and a variety of induction regimens in 297 women. The most common medication used for induction abortion was misoprostol. Women treated with misoprostol experienced fewer complications than those induced with other agents, but more than women undergoing D&E (22% vs. 4%, p<0.001). However, women undergoing medical abortion were of a higher gestational age than those undergoing D&E (20.3 ± 2 weeks vs. 18.4 ± 2.2 weeks, p<0.001) which may have biased the outcomes. In addition, most of the complications seen in the medical abortion group were retained placenta, requiring surgical evacuation. This complication is less common with combined mifepristone–misoprostol protocols.

Performance of randomised trials of D&E and current medical abortion regimens has proved difficult. Where surgical termination is offered, women appear less likely to accept the possibility of randomisation to a labor induction. Grimes and colleaguesCitation18 explored the feasibility of such a trial, comparing D&E to mifepristone and misoprostol, in the United States. In 24 months, 18 women were successfully recruited to the study; 62% of eligible women declined participation. Due to the small sample size, the outcomes of the study were imprecise. However, the trial was able to demonstrate that women randomised to medical termination were more likely to experience one or more adverse events than those assigned to D&E (RR 6.0, 95% CI 0.9–40.3, p=0.05). Pain was reported as significantly higher in the mifepristone–misoprostol group (p=0.03); but there were no statistical differences in either acceptability or satisfaction between groups.

Relative frequency of D&E and medical abortion

The relative frequencies of D&E and medical abortion in the second trimester vary. In the United States, D&E predominates, used for 99% of abortions between 13–15 weeks, 95% between 16–20 weeks, and 85% at 21 weeks or later.Citation19 Similarly, D&E is the method of choice in 75% of abortions greater than 13 weeks gestation in England and Wales.Citation20 D&E has been described as common in the Netherlands, France and parts of Australia.Citation21 In contrast, in Nordic countries, Scotland and Viet Nam most abortions in the second trimester are performed medically.Citation22Citation23

The reasons for these variations are likely multifactorial. Specialised training and the maintenance of an adequate caseload are required to perform D&E safely.Citation24 Acquiring this skill can be challenging since many training programmes fail to provide adequate instruction in surgical abortion techniques.Citation25Citation26 In the United States, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has mandated that residency curricula include induced abortion. This stipulation has increased abortion training nationwide. However, D&E remains less likely to be taught than first trimester vacuum aspiration.Citation25 Individual programmes may also decide whether abortion training is incorporated as a requirement (unless a resident demonstrates a moral objection) or as an elective (residents choose to receive training). More residents in programmes with required training gain exposure to D&E and, importantly, perform more D&Es. Achieving competency in abortion procedures during training is associated with future abortion provision, which emphasises the importance of integrated training.Citation27Citation28

Advantages and disadvantages

Procedural choice may also be affected by the availability of necessary equipment, the ability to book operating room time, facility policies, staff acceptability and patient preference.Citation29 Some providers may find it distressing to perform D&E at advanced gestations.Citation30 Compared to a medical abortion, where a physician may be largely uninvolved during the course of labour and may or may not attend the delivery, a surgeon undertaking a D&E must “deal with the second trimester fetus in an intimate, physical way”.Citation31 Although nurses and other support staff may be affected by the conduct of the D&E procedure, they may find it less burdensome as their involvement is less direct. Little is known regarding women's preferences for abortion in the second trimester. Studies comparing medical abortion to vacuum aspiration in the first trimester have demonstrated that many women have a preference between methods and that obtaining their method of choice is a strong predictor of satisfaction.Citation32 However, when randomly allocated, women without a strong preference report vacuum aspiration to be significantly more acceptable, a finding that has been shown to persist up to two years following treatment.Citation33

Advantages of D&E for both provider and patient are that the procedure can be scheduled on an outpatient basis and operating times are short, as opposed to the unpredictable duration of a medical abortion, which requires hospitalisation. For some women, avoiding surgery or anaesthesia with a medical abortion may outweigh these benefits. For women terminating a pregnancy due to aneuploidy or fetal anomalies, medical abortion has been advocated as it allows for bonding with the fetus after delivery, which may assist in the grieving process. However, one study comparing women self-selecting medical or surgical termination for these indications found no difference in grief resolution.Citation34 Additionally, specimens obtained from D&E abortions are adequate to confirm pathologic and cytologic diagnoses when necessary.Citation35Citation36

An evolving technique

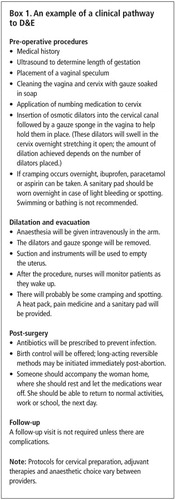

Surgical abortion in the second trimester of pregnancy continues to evolve. Variations in methods of cervical preparation, instrumentation and adjuvant therapies such as feticide are practised to ensure safe and efficient uterine evacuation. Box 1shows the main steps involved in a D&E.

The current nomenclature for second trimester surgical abortion is gestational-age dependent. A D&E refers to any instrumental evacuation of the pregnant uterus through the cervix at ≥13 weeks gestation.Citation7 This operational definition was proposed by the US Centers for Disease Control to differentiate second trimester curettage procedures from first trimester procedures (vacuum aspiration or suction curettage). Although vacuum aspiration can be performed to 16 weeks gestation using large-bore cannulae (14–16 mm in diameter),Citation37 by convention this would be referred to as a D&E.

Cervical preparation

A guiding principle in second trimester surgical abortion is to achieve sufficient expansion of the cervical os so that the relatively larger and ossified fetal parts can be removed and the risk of injury minimised. This may be achieved by mechanical dilatation with graduated rigid dilators, slowly expanding cervical tents, or with medications, such as misoprostol or mifepristone.

There are three types of absorptive natural or synthetic cervical tents (osmotic dilators), which after insertion for several hours, either soften the cervix significantly, allowing for easier mechanical dilatation, or exert outward pressure on the endocervical canal, stretching it adequately for instrumentation. Laminaria are the most common osmotic dilator used. Made of compressed stalks of seaweed (Laminaria japonica or Laminaria digitata), they range from 2–10 mm in diameter and 60–85 mm in length. After insertion, laminaria expand to three or four times their dry diameter and may also ripen the cervix by inducing the release of prostaglandins.Citation38 Although some dilation is measurable three hours after insertion, 12–24 hours are required for maximal expansion of the tents. Dilapan-S is a synthetic rod made of polyacrylate-based hydrogel and is available in three sizes (3×55 mm, 4×55 mm and 4×65 mm). Like laminaria, Dilapan expands radially, however this occurs more rapidly, consistently and to a greater degree, meaning that fewer Dilapan can be inserted for shorter periods of time. Lamicel is a stiff polyvinyl alcohol polymer sponge impregnated with magnesium sulfate. The Lamicel sponge rapidly absorbs fluid from the cervical tissue and stimulates collagen breakdown to soften the cervix.Citation39

Prior to D&E at 14–16 weeks gestation, a single Lamicel leads to comparable degrees of difficulty in subsequent dilatation and rates of adequate dilation as multiple laminaria.Citation40 A small randomised trial of overnight Dilapan or Lamicel prior to abortion at 13–16 weeks gestation demonstrated that Dilapan produces greater dilation, which is consistent with differences in mechanism of action.Citation41 Lamicel is approved for use to 16 weeks gestation. It is less commonly used beyond this gestational age because of concern regarding the lack of radial force exerted by the sponge when greater cervical dilation is required.Citation21

Laminaria or Dilapan are more commonly used prior to D&E at higher gestations. They are associated with a lower risk of cervical trauma and uterine perforation than mechanical dilatation.Citation42Citation43 Few studies have directly compared laminaria to Dilapan. One series evaluated outcomes in 1,001 women who underwent D&E at 13–25 weeks gestation, and received either laminaria or Dilapan 18–24 hours before surgery.Citation44 No differences were found in procedure time, blood loss or need for additional dilatation. However, more laminaria were required to achieve the same amount of dilation achieved with Dilapan. The older formulation of Dilapan used in this study was prone to difficult removals and fragmentation which occurred in 6% of cases. The current, commercially available product (Dilapan-S) elongates with traction in order to avoid fracturing and entrapment.

Preference for Dilapan or laminaria is largely provider-dependent. There is no standard protocol for the use of osmotic dilators. In general, the number used and length of time the dilators are left in situ increases with gestational age. Some providers use a combination of Dilapan and laminaria or perform serial insertions over two or more days, depending on the desired amount of dilation.Footnote*

The placement of osmotic dilators requires insertion of a vaginal speculum, followed by cleansing of the cervix and often, administration of a local anaesthetic. The dilators are then inserted into the cervical canal using gentle pressure. Discomfort can occur during insertion and many women experience cramping as the dilators expand. This process may be viewed by some women and clinicians as unsatisfactory. In addition, osmotic dilators are not available worldwide and are typically left in place overnight, which may present a barrier for women travelling long distances to access care.Citation23 The prostaglandin analogue misoprostol has been investigated as an alternative. Misoprostol is cheap, widely available, and can be (self-)administered by a variety of routes including oral, vaginal, sublingual and buccal.

The ideal dose, route and upper gestational age limit of misoprostol administration before D&E has not been determined. Like Lamicel, misoprostol softens rather than expands the cervical os. Misoprostol can induce uterine cramping and gastrointestinal side effects, which may affect acceptability. The risk of inadvertent abortion outside of the health care facility is another concern when misoprostol is administered at home.

Buccal misoprostol, in doses ranging from 400–800 mcg, appears to achieve adequate cervical preparation up to 18 weeks gestation.Citation23,45,46 One randomised trial compared 400 mcg vaginal misoprostol 3–4 hours before surgery to 3–6 medium laminaria placed overnight in women at 13–16 weeks gestation.Citation47 The use of misoprostol was associated with less pre-operative cervical dilation, longer operating times and a more frequent need for additional manual dilatation. One woman required an additional dose of misoprostol; however, all procedures were able to be completed and more women preferred a same-day cervical preparation regimen.

The combined use of misoprostol and osmotic dilators has been explored to reduce the number of visits and duration of time necessary for cervical preparation. One placebo-controlled, randomised trial compared overnight laminaria with 400 mcg buccal misoprostol or placebo 60–90 minutes pre-operatively at 13–20 weeks gestation.Citation48 Significant improvement in cervical dilation was only observed in the subset of subjects with pregnancies 19 weeks and above, the magnitude of which was two dilator sizes or similar to what would be achieved with a second set of laminaria. One small case series has reported outcomes with 400–800 mcg vaginal misoprostol in combination with Dilapan 4–7 hours prior to D&E at 20–24 weeks gestation.Citation49 Of 25 cases audited, all were able to be completed. However, 19 (76%) required further cervical dilatation intra-operatively and three cervical lacerations requiring repair were encountered. Further research is needed to determine the utility of combined regimens, particularly at shorter intervals.

Mifepristone, taken orally 24–48 hours prior to first trimester surgical abortion, has been shown to be as effective as gemeprostCitation50 and more effective than vaginal misoprostolCitation51 at ripening the cervix. Some surgeons exploit the priming effect of mifepristone before D&E, even preferring it to misoprostol (C Paterson, personal communication, 26 June 2008). Carbonell and colleagues have published the only study which examines the utility of mifepristone prior to D&E.Citation52 Women at 12–20 weeks gestation were randomly allocated to either 200 mg oral mifepristone 48 hours before 600 mcg vaginal or sublingual misoprostol 1.5–2.5 hours prior to D&E or misoprostol alone. Thirty per cent of women in the mifepristone–misoprostol group and 54% of those in the misoprostol-only groups also received one Dilapan intra-cervical tent. Greater mean pre-operative cervical dilation was achieved with the addition of mifepristone; however, notably, several women in this group aborted spontaneously before surgery, two after receiving mifepristone alone and 15 pre-treated with mifepristone but after administration of misoprostol. There are as yet no studies that assess mifepristone alone for cervical preparation before D&E or which compare mifepristone to other methods of cervical preparation, such as osmotic dilators. In addition, mifepristone currently has a higher cost and more limited availability globally than misoprostol, which may have an impact on its wider use.

Commonest method of D&E and variantsFootnote*

The commonest method of D&E involves disarticulation and removal of the fetus through the prepared cervix using strong, elongated extraction forceps. Passive or active drainage of amniotic fluid by electric suction occurs prior to removal of the fetus and placenta and a final suction curettage is performed at the end of the procedure to remove any remaining blood or pregnancy tissue. Castleman and colleagues have described a version of D&E adapted for use in low-resource settings. The protocol uses buccal misoprostol for cervical preparation, forceps and a manual vacuum aspirator (MVA) instead of an electric suction machine.Citation23 In a demonstration project in Viet Nam, this protocol was shown to be effective between 13–18 weeks gestation. Another variant is known as intact dilatation and extraction (D&X). Wide cervical dilatation is achieved with two or more days of laminaria. This is followed by an assisted breech delivery of the trunk of the fetus, decompression of the calvarium, and delivery of the fetus otherwise intact. The greater degree of cervical dilation (reported as a median of 5 cm, range 2–10) and mode of evacuation mean that fewer instrument passes are made with D&X than D&E, ostensibly reducing the risk of complications and making the procedure faster. In a retrospective comparison of D&X and D&E, procedure time, complications, and blood loss were not statistically different, even though the cases performed intact were of significantly higher gestational ages.Citation53 Three women had complications requiring admission to the surgical intensive care unit, including the only case of uterine perforation in the cohort, all of which were in the D&E group.

Agents for fetal demise prior to D&E

Feticidal agents are used before D&E by some surgeons. The softening of cortical bone that occurs after fetal demise is proposed to reduce the amount of cervical dilation necessary and to make the procedure easier and faster, thus reducing the risk of complications. The true incidence of use is not known and the gestational age at which fetal demise is induced differs among practitioners; however, it is typically reserved for terminations above 18 weeks gestation. The most common medications used are potassium chloride and digoxin. Potassium chloride is injected trans-abdominally under ultrasound guidance into the fetal cardiac ventricle or thorax. Digoxin can be administered by these routes into the amniotic fluid or other fetal tissues.

Intra-cardiac potassium chloride is the most common agent used in the United Kingdom to comply with the recommendation by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists for induced fetal demise before medical abortion at ≥22 weeks gestation.Citation24 Intra-cardiac potassium chloride for this indication in the UK has led to extension of its use before surgical abortion. Digoxin use is more commonly described in the United States.Citation21 Administration of either medication is safe.Citation54Citation55 However, while intra-cardiac potassium chloride has been reported to be uniformly effective, failure to achieve fetal demise has been reported with digoxin, which appears to be related to both the dose and route of administration.Citation56

Data supporting the effect of fetal demise on the safety and efficiency of D&E are limited. Large, non-comparative case series utilising intra-fetal digoxin, urea and multiple sets of laminaria for cervical preparation reported a low incidence of complications.Citation57Citation58 However, one randomised, controlled trial showed no difference between intra-amniotic digoxin and placebo with regard to complication rates or procedure duration when administered prior to D&E at 20–24 weeks gestation.Citation59 Symptoms after injection were similar in both groups, with the exception of vomiting, which was significantly more frequent in the digoxin group (16.1% vs. 3.1%, p=.02). Women in this study, did, however, report a strong preference for fetal death prior to the abortion (92% in both groups).

Complications of D&E

Bleeding is the most common complication of second trimester surgical abortion and the risk of haemorrhage increases with gestational age.Citation60 Excessive blood loss may occur as a result of injury to the uterus or cervix, an incomplete procedure, or failure of the uterus to contract adequately after evacuation. The risk of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is also elevated with second as compared to first trimester surgical abortion.Citation61

Approaches to reducing blood loss include the use of uterotonics, such as oxytocin or ergot derivatives, and local vasoconstrictors. Oxytocin in crystalloid may be initiated at the beginning or end of the operation as an intravenous infusion. Oxytocin or methylergometrine can also be administered as a bolus intramuscular, intravenous or intra-cervical injection. The utility of these agents in reducing blood loss with D&E is unclear, although they are commonly used. One randomised trial of intravenous methylergometrine did not demonstrate a decrease in blood loss.Citation62 An alternative is the administration of vasopressin injected para- or intra-cervically before surgery. In a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, four units of vasopressin combined with the cervical anaesthestic significantly decreased blood loss during D&E at greater than 14 weeks gestation.Citation63 Compared to placebo, the effect of vasopressin on mean blood loss was greater as gestational age advanced.

Uterine perforation is a potentially serious complication of second trimester surgical abortion, with a reported incidence of 0.2–0.4%.Citation60,64,65 Although perforations during first trimester abortion may be managed expectantly or with laparoscopy, those occurring with the larger instruments used for D&E typically require exploratory laparotomy and are often associated with bowel injury, haemorrhage, and, in some cases, hysterectomy.Citation60Citation66 The use of routine intra-operative ultrasound guidance during D&E has been shown to reduce the rate of perforation.Citation65

Not all providers use ultrasound during D&E or have this technology available in the procedure room. Completion of the D&E therefore relies solely on a clinician's tactile sensation. Most evacuations can be completed from the lowest part of the uterine cavity and perforations are more likely to occur when instruments are passed high into the uterus. Thus, diligent attention to correct placement of instruments is important, whether or not ultrasound is used. Under-estimation of gestational age is also associated with perforation, so accurate determination of gestational age is essential. This is typically ascertained using sonographic measurements.Citation66 Ultrasound is also useful in cases where the surgeon experiences difficulty locating or removing fetal parts. Thus, even if an ultrasound machine is not used regularly in the operating room during the surgery, having one on-site and accessible is helpful.Citation67

Use of a “no-touch” technique, which ensures that the tips of instruments never contact non-sterile surfaces before entering the uterus, inspection of the evacuated tissue to verify complete removal, and the provision of routine antibiotic prophylaxis are other measures used to prevent complications. Although some complications such as perforation remain more serious when they occur during D&E, overall complication rates with second trimester surgical abortion have been reported as being no higher than those occurring in the first trimester.Citation68

Historically, concern was raised regarding the degree of pre-operative cervical dilation required for D&E and poor pregnancy outcomes such as cervical incompetence, miscarriage, and preterm birth. Recent retrospective case series and one retrospective case–control study did not find an association between D&E and future pregnancy complications.Citation69–71 Preterm delivery did appear less likely when greater pre-operative cervical dilation was achieved with laminaria, possibly because of less associated cervical trauma than with mechanical dilatation.Citation70 There are no data regarding the influence of misoprostol, which commonly requires additional manual dilatation when used for cervical preparation before D&E, and the outcome of subsequent pregnancies.

Surgical abortion in the second trimester can be performed using light or deep intravenous sedation or local anaesthesia injected para- or intra-cervically, often with the addition of oral, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, narcotics or anxiolytics. Data from the 1970s demonstrated a major complication rate of 0.72 per 100 abortions for general anaesthesia and 0.32 per 100 abortions for local anaesthesia.Citation72 Since that time, advances have been made in anaesthetic technique and monitoring. More recent data on the comparative risks of local vs. general anaesthesia with D&E are lacking. However a case series reporting on 170,000 first trimester surgical abortions found comparable rates among anaesthetic techniques.Citation73

Surgical methods of second trimester abortion are common today and the techniques used continue to be refined. Debate still exists as to whether surgical or medical abortion is optimal for second trimester pregnancy termination, and a continuing challenge to provision is the availability of a large pool of skilled providers. However, for those women able to access this option, D&E is a safe, efficient and cost-effective means of pregnancy termination in the second trimester.

Notes

* There are several protocols for Dilapan and laminaria insertion by gestational age, which are described in detail in: Paul M, Lichtenberg ES, Borgatta L, et al, editors. A Clinician's Guide to Medical and Surgical Abortion. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1999.

* Baird TL, Castleman LD, Hyman AG, et al. Clinician's Guide for Second-Trimester Abortion (2nd ed. Chapel Hill NC: Ipas, 2007) includes service delivery and management considerations and protocols for both D&E and medical abortion procedures, and is applicable in high- or low-resource settings.

References

- C Tietze, S Lewit. Joint program for the study of abortion (JPSA): Early medical complications of legal abortion. Studies in Family Planning. 3(6): 1972; 97–123.

- W Cates Jr, KF Schulz, DA Grimes. Dilatation and evacuation procedures and second-trimester abortions. The role of physician skill and hospital setting. Journal of American Medical Association. 248(5): 1982; 559–563.

- Y Manabe, A Nakajima. Laminaria-metreurynter method of midterm abortion in Japan. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 40(4): 1972; 612–614.

- I Bierer, V Steiner. Termination of pregnancy in the second trimester with the aid of laminaria tents. Medical Gynaecology and Sociology. 6(1): 1972; 9–10.

- DA Grimes, W Cates Jr. Instrumental abortion in the second trimester: an overview. MJ Keirse, JB Gravenhorst, DA Van Lith, MP Embrey. Second trimester pregnancy termination. 1982; Martinus Nijhoff: The Hague, 65–79.

- ME Kafrissen, KF Schulz, DA Grimes. Midtrimester abortion. Intra-amniotic instillation of hyperosmolar urea and prostaglandin F2 alpha v dilatation and evacuation. Journal of American Medical Association. 251(7): 1984; 916–919.

- DA Grimes, KF Schulz, W Cates Jr. Mid-trimester abortion by dilatation and evacuation: a safe and practical alternative. New England Journal of Medicine. 296(20): 1977; 1141–1145.

- DA Grimes, JF Hulka, ME McCutchen. Midtrimester abortion by dilatation and evacuation versus intra-amniotic instillation of prostaglandin F2 alpha: a randomised clinical trial. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 137: 1980; 7.

- WE Brenner, DA Edelman. Dilatation and evacuation at 13 to 15 weeks' gestation versus intra-amniotic saline after 15 weeks' gestation. Contraception. 10(2): 1974; 171–180.

- KI Cadesky, E Ravinsky, ER Lyons. Dilation and evacuation: a preferred method of midtrimester abortion. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 139(3): 1981; 329–332.

- AM Altman, PG Stubblefield, JF Schlam. Midtrimester abortion with laminaria and vacuum evacuation on a teaching service. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 30(8): 1985; 601–606.

- T Crist, P Williams, SH Lee. Midtrimester pregnancy termination: a study of the cost effectiveness of dilation and evacuation in a free-standing facility. North Carolina Medical Journal. 44(9): 1983; 549–551.

- OS Tang, PC Ho. Medical abortion in the second trimester. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 16(2): 2002; 237–246.

- DR Urquhart, A Templeton. The use of mifepristone prior to prostaglandin-induced mid-trimester abortion. Human Reproduction. 5(7): 1990; 883–886.

- MW Rodger, DT Baird. Pretreatment with mifepristone (RU-486) reduces interval between prostaglandin administration and expulsion in second trimester abortion. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 97(1): 1990; 41–45.

- KJ Thong, DT Baird. Induction of second trimester abortion with mifepristone and gemeprost. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 100: 1993; 758–761.

- Autry AM, Hayes EC, Jacobson GF, et al. A comparison of medical induction and dilation and evacuation for second-trimester abortion. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2002 2002/8;187(2):393–97.

- DA Grimes, SM Smith, AD Witham. Mifepristone and misoprostol versus dilation and evacution for midtrimester abortion: a pilot randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 111: 2004; 148–153.

- LD Elam-Evans, LT Strauss, J Herndon. Abortion surveillance – United States, 2000. Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries. 52(SS-12): 2003; 1–32.

- Department of Health. Abortion Statistics, England and Wales: 2007. Statistical Bulletin 2008/1. 2008; Crown: London.

- WM Haskell, TR Easterling, ES Lichtenberg. Surgical abortion after the first trimester. M Paul, ES Lichtenberg, L Borgatta. A Clinician's Guide to Medical and Surgical Abortion. 1999; Churchill Livingstone: Philadelphia, 123–138.

- STAKES. Official statistics of Finland. Induced abortions and sterilisations 2005. Statistical Summary; 2006.

- LD Castleman, KTH Oanh, AG Hyman. Introduction of the dilation and evacuation procedure for second-trimester abortion in Vietnam using manual vacuum aspiration and buccal misoprostol. Contraception. 74(3): 2006; 272–276.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The Care of Women Requesting Induced Abortion. 2004; RCOG Press: London.

- KL Eastwood, JE Kacmar, J Steinauer. Abortion training in United States obstetrics and gynecology residency programs. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 108(2): 2006; 303–308.

- G Roy, R Parvataneni, B Friedman. Abortion training in Canadian obstetrics and gynecology residency programs. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 108(2): 2006; 308–314.

- J Steinauer, M Silveira, R Lewis. Impact of formal family planning residency training on clinical competence in uterine evacuation techniques. Contraception. 76(5): 2007; 372–376.

- J Steinauer, U Landy, H Filippone. Predictors of abortion provision among practicing obstetrician–gynecologists: a national survey. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 198(1): 2008; 39.

- LE Ferris, M McMain-Klein, K Iron. Factors influencing the delivery of abortion services in Ontario: a descriptive study. Family Planning Perspectives. 30(3): 1998; 134–138.

- NB Kaltreider, S Goldsmith, AJ Margolis. The impact of midtrimester abortion techniques on patients and staff. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 135(2): 1979; 235–238.

- JB Rooks, W Cates Jr. Emotional impact of D&E vs. instillation. Family Planning Perspectives. 9(6): 1977; 276–277.

- RC Henshaw, SA Naji, IT Russell. Comparison of medical abortion with surgical vacuum aspiration: women's preferences and acceptability of treatment. British Medical Journal. 307(6906): 1993; 714–717.

- FL Howie, RC Henshaw, SA Naji. Medical abortion or vacuum aspiration? Two year follow up of a patient preference trial. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 104: 1997; 829–833.

- GA Burgoine, SD Van Kirk, J Romm. Comparison of perinatal grief after dilation and evacuation or labor induction in second trimester terminations for fetal anomalies. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 192(6): 2005; 1928–1932.

- LP Shulman, FW Ling, CM Meyers. Dilation and evacuation for second-trimester genetic pregnancy termination. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 75(6): 1990; 1037–1040.

- BA Bernick, DD Ufberg, R Nemiroff. Success rate of cytogenetic analysis at the time of second-trimester dilation and evacuation. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 179(4): 1998; 957–961.

- PG Stubblefield, BH Albrecht, B Koos. A randomized study of 12mm and 15.9mm cannula in midtrimester abortion by laminaria and vacuum curettage. Fertility and Sterility. 29(5): 1978; 512–517.

- E El Maradny, N Kanayama, A Halim. Biochemical changes in the cervical mucus after application of laminaria tent. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 75(3): 1996; 203–207.

- KH Nicolaides, CC Welch, EN Koullapis. Cervical dilatation by lamicel: studies on the mechanism of action. British Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 90(11): 1983; 1060–1064.

- DA Grimes, IG Ray, CJ Middleton. Lamicel versus laminaria for cervical dilation before early second-trimester abortion: a randomized clinical trial. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 69(6): 1987; 887–890.

- EC Wells, JF Hulka. Cervical dilation: a comparison of lamicel and dilapan. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 161(5): 1989; 1124–1126.

- DA Grimes, KF Schulz, W Cates Jr. Prevention of uterine perforation during curettage abortion. Journal of American Medical Association. 251: 1984; 2108–2111.

- KF Schulz, DA Grimes, W Cates Jr. Measures to prevent cervical injury during suction curettage abortion. Lancet. 8335(1): 1983; 1182–1185.

- WM Hern. Laminaria versus dilapan osmotic cervical dilators for outpatient dilation and evacuation abortion: randomized cohort comparison of 1001 patients. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 171(5): 1994; 1324–1328.

- CS Todd, M Soler, L Castleman. Buccal misoprostol as cervical preparation for second trimester pregnancy termination. Contraception. 65(6): 2002; 415–418.

- A Patel, E Talmont, J Morfesis. Adequacy and safety of buccal misoprostol for cervical preparation prior to termination of second-trimester pregnancy. Contraception. 73(4): 2006; 420–430.

- AB Goldberg, EA Drey, AK Whitaker. Misoprostol compared with laminaria before early second-trimester surgical abortion: a randomized trial. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 106(2): 2005; 234–241.

- AB Edelman, JG Buckmaster, MF Goetsch. Cervical preparation using laminaria with adjunctive buccal misoprostol before second-trimester dilation and evacuation procedures: a randomized clinical trial. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 194: 2006; 425–430.

- LCY Poon, J Parsons. Audit of the effectiveness of cervical preparation with dilapan prior to late second-trimester (20–24 weeks) surgical termination of pregnancy. BJOG. 114(4): 2007; 485–488.

- RC Henshaw, AA Templeton. Pre-operative cervical preparation before first trimester vacuum aspiration: a randomized controlled comparison between gemeprost and mifepristone (RU 486). British Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 98(10): 1991; 1025–1030.

- PW Ashok, GM Flett, A Templeton. Mifepristone versus vaginally administered misoprostol for cervical priming before first-trimester termination of pregnancy: a randomized, controlled study. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecolology. 183(4): 2000; 998–1002.

- JL Carbonell, FG Gallego, MP Llorente. Vaginal vs. sublingual misoprostol with mifepristone for cervical priming in second-trimester abortion by dilation and evacuation: a randomized clinical trial. Contraception. 75(3): 2007; 230–237.

- ST Chasen, RB Kalish, M Gupta. Dilation and evacuation at >/=20 weeks: comparison of operative techniques. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 190(5): 2004; 1180–1183.

- E Drey, L Thomas, N Benowitz. Safety of intra-amniotic digoxin administration before late second-trimester abortion by dilation and evacuation. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 182: 2000; 1063–1066.

- L Pasquini, V Pontello, S Kumar. Intracardiac injection of potassium chloride as method for feticide: experience from a single UK tertiary centre. BJOG. 115(4): 2008; 528–531.

- M Molaei, HE Jones, T Weiselberg. Effectiveness and safety of digoxin to induce fetal demise prior to second-trimester abortion. Contraception. 77(3): 2008; 223–225.

- WM Hern. Laminaria, induced fetal demise and misoprostol in late abortion. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 75: 2001; 279–286.

- WM Hern, C Zen, KA Ferguson. Outpatient abortion for fetal anomaly and fetal death from 15–34 menstrual weeks' gestation: techniques and clinical management. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 81: 1993; 301–306.

- RA Jackson, VL Teplin, EA Drey. Digoxin to facilitate late second-trimester abortion: a randomized, masked, placebo-controlled trial. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 97: 2001; 471–476.

- WF Peterson, FN Berry, MR Grace. Second-trimester abortion by dilatation and evacuation: an analysis of 11,747 cases. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 62(2): 1983; 185–190.

- ME Kafrissen, MW Barke, P Workman. Coagulopathy and induced abortion method, rates and relative risks. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 147: 1983; 344–345.

- G Woodward. Intraoperative blood loss in midtrimester dilatation and extraction. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 62(1): 1983; 69–72.

- KF Schulz, DA Grimes, DD Christensen. Vasopressin reduces blood loss from second-trimester dilatation and evacuation abortion. Lancet. 2: 1985; 353–356.

- BR Pridmore, DG Chambers. Uterine perforation during surgical abortion: a review of diagnosis, management and prevention. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 39(9): 1999; 349–353.

- PD Darney, RL Sweet. Routine intraoperative ultrasonography for second trimester abortion reduces incidence of uterine perforation. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 8(2): 1989; 71–75.

- PD Darney, E Atkinson, K Hirabayashi. Uterine perforation during second-trimester abortion by cervical dilation and instrumental extraction: a review of 15 cases. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 73(3): 1990; 441–444.

- TL Baird, LD Castleman, G Alyson. Clinician's Guide for Second-Trimester Abortion. 2nd ed., 2007; Ipas: Chapel Hill NC.

- FR Jacot, C Poulin, AP Bilodeau. A five-year experience with second-trimester induced abortions: no increase in complication rate as compared to the first trimester. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 168(2): 1993; 633–637.

- ST Chasen, RB Kalish, M Gupta. Obstetric outcomes after surgical abortion at >/= 20 weeks' gestation. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 193(3): 2005; 1161–1164.

- RB Kalish, ST Chasen, LB Rosenzweig. Impact of midtrimester dilation and evacuation on subsequent pregnancy outcome. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 187(4): 2002; 882–885.

- JE Jackson, WA Grobman, E Haney. Mid-trimester dilation and evacuation with laminaria does not increase the risk for severe subsequent pregnancy complications. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 96(1): 2007; 12–15.

- HT MacKay, KF Schulz, DA Grimes. Safety of local versus general anesthesia for second-trimester dilatation and evacuation abortion. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 66(5): 1985; 661–665.

- E Hakim-Elahi, HMM Tovell, MS Burnhill. Complications of first trimester abortion: a report of 170,000 cases. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 76: 1990; 129–135.