Abstract

High sex ratios at birth (108 boys to 100 girls or higher) are seen in China, Taiwan, South Korea and parts of India and Viet Nam. The imbalance is the result of son preference, accentuated by declining fertility. Prenatal sex detection with ultrasound followed by second trimester abortion is one of the ways sex selection manifests itself, but it is not the causative factor. Advocates and governments seeking to reverse this imbalance have largely prohibited sex detection tests and/or sex selective abortion, assuming these measures would reverse the trend. Such policies have been difficult to enforce and have met with only limited success. At the same time, such policies are starting to have adverse effects on the already limited access to safe and legal second trimester abortion for reasons other than sex selection. Moreover, the sex selection issue is being used as a platform for anti-abortion rhetoric by certain groups. Maintaining access to safe abortion and achieving a decline in high sex ratios are both important goals. Both are possible if the focus shifts to addressing the conditions that drive son preference.

Résumé

Des rapports de masculinité élevés (108 garçons ou plus pour 100 filles) sont observés en Chine, à Taiwan, en République de Corée et dans des régions de l'Inde et du Viet Nam. Ce déséquilibre est le résultat de la préférence pour les enfants de sexe masculin qu'accentue la baisse de la fécondité. La détection prénatale du sexe par ultrasons suivie d'un avortement du deuxième trimestre est l'une des manifestations de la sélection du sexe du bébé, mais ce n'en est pas la cause. Habituellement, les activistes et les autorités souhaitant corriger ce déséquilibre ont interdit les tests de détection du sexe et/ou l'avortement sélectif, supposant que ces mesures renverseraient la tendance. Ces politiques ont été difficiles à appliquer et n'ont guère obtenu de résultats. En même temps, elles commencent à avoir des effets néfastes sur l'accès déjà limité à l'avortement sûr et légal du deuxième trimestre pour des raisons autres que la sélection du sexe du bébé. De plus, certains groupes opposés à l'avortement utilisent la question de la sélection du sexe comme plateforme pour leur propagande. Maintenir l'accès à un avortement médicalisé et parvenir à diminuer les rapports élevés de masculinité sont deux objectifs importants. Tous deux sont possibles en réorientant les priorités de manière à s'attaquer aux facteurs qui induisent la préférence pour les garçons.

Resumen

En China, Taiwán, Corea del Sur y partes de la India y Viet Nam, se ve un predominio de varones en la proporción de sexos entre recién nacidos (108 varones por 100 niñas o más). Ese desequilibrio es el resultado de la preferencia por hijos varones, acentuada por el deterioro de la fertilidad. La detección prenatal del sexo con ecografía, seguida del aborto en el segundo trimestre es una de las formas en que se manifiesta la selección del sexo, pero no son los factores causantes. Los defensores y gobiernos que buscan cambiar ese desequilibrio han prohibido en gran medida las pruebas para la detección del sexo y/o el aborto para la selección del sexo, suponiendo que estas medidas invertirían el sentido de la tendencia. Ha sido difícil hacer cumplir dichas políticas, que han tenido un éxito limitado y, al mismo tiempo, están empezando a tener efectos adversos en el acceso ya limitado al aborto seguro y legal en el segundo trimestre por motivos además de la selección del sexo. Más aún, ciertos grupos están utilizando el tema de la selección del sexo como una plataforma para la retórica anti-aborto. Mantener el acceso al aborto seguro y lograr una disminución en las altas proporciones entre sexos son ambas metas importantes. Las dos son posibles si el enfoque se dirige hacia tratar las condiciones que guían su preferencia.

The natural sex ratio at birth is usually 104–107 boys to 100 girls.Citation1 Higher ratios (a disproportionally larger number of boys being born) are suggestive of sex selection. Estimates vary but several countries in East and South Asia (China, South Korea, Taiwan, India) have a birth sex ratio of 108 or more.Citation2

This paper looks at the links between the imbalanced sex ratio and sex selection in Asia and how some NGOs and governments have responded, why sex selection and abortion have become so intertwined, and what some possible ways to move forward are.

Sex ratio imbalances: where and why

National averages of sex ratio at birth can mask many variations. In China, all but the two ethnic provinces of Tibet and Xinjiang have high sex ratios.Citation3 In India, on the other hand, the imbalance is seen largely in the north and west of the country (the states of Punjab, Haryana, Delhi, Himachal Pradesh, Rajasthan and parts of Gujarat and Maharashtra). Of the country's 593 districts, 49 (8.2%) have a ratio of 117 or higher, while 258 districts (43.5%) have a sex ratio at birth of 105 or lower.Citation4 Footnote*

Though the national average in Viet Nam is not significantly elevated, imbalances have been documented in several provinces.Citation5Citation6 In Nepal, though concerns have been raised about the future, it is only two districts bordering India that have a birth sex ratio of 108 or more.Citation7 Wherever skewed ratios are seen, the sex ratio of first births is usually within or close to the biologically normal range. Imbalances grow as birth order increases.Citation3,8–10

It is widely agreed that the growing imbalance in the ratios seen in these countries in the last two decades is associated with prenatal sex determination with ultrasound, which becomes possible around 13–14 weeks of pregnancy, followed by an abortion primarily for sex selection during the second trimester.Citation3,8,11,12 However, sex ratio at birth is also affected by other factors. Female births may remain unregistered. Girls who are killed shortly after birth or given away for adoption may remain unaccounted for. Though we talk of sex ratio at birth, in most countries, because reliable birth registration data is not available, it is actually the childhood sex ratio (0–4 or 0–6 years) that is used as a proxy. In addition to factors that affect sex ratios at birth, this ratio is also affected by selective under-counting of girls in census enumerations and more importantly by the discriminatory feeding and health care practices that cause an increase in post-neonatal mortality in girls. In fact, higher than normal childhood sex ratios have been documented in both China and India from as early as the mid-20th century when these data first became available. All of these affect the sex ratio to varying degrees, depending on the country and context.Citation3,6,8,11,12

The temporal association between sex detection, abortion for sex selection and an altered sex ratio does not mean there is a simple cause-and-effect relationship. Where the causal condition of son preference does not exist (e.g. South India, Japan) the availability of ultrasound and abortion do not lead to their use for sex selective discrimination. Conversely, son preference may be imported into countries without this culture through immigration. Thus, sex ratio imbalances have been seen among children of Asian-origin parents in the United States and Britain.Citation13Citation14

Son preference is strong in all of the Asian countries where sex ratio elevations have been seen. Patrilineal inheritance and kinship as well as patrilocality make boys more valuable to the natal family. Farm-dependent economies require male workers and in the absence of state-sponsored schemes, sons take responsibility for ensuring old age security for their parents. In south Asia, the dowry system adds to the economic disadvantage of girls. Religious traditions (sons perform death rites in Hindu tradition and ancestor worship in the Confucian tradition) also encourage son preference.Citation3,6,7,9,15

The preference for sons is accentuated as fertility declines and women want to achieve the dual goals of a small family and one or more sons. These pressures become more pronounced when population policies are in place. Through the 1970s and 80s, India actively promoted a two-child norm and mass awareness campaigns; visuals of the ideal family composition (one boy and one girl) were ubiquitous. Though this targeted approach has been officially discontinued in recent years, sporadic use of disincentives does continue. Viet Nam also has a two-child policy though enforcement has been variable. The most extreme pressures are seen in China, where the one- and two-child policies, though relatively less strict now, are still actively enforced through pregnancy monitoring, use of long-term contraception with abortion and heavy penalties for violators.Citation3,6,8,10

An imbalanced sex ratio is an indicator of the extent to which son preference exists, but the converse – a normal sex ratio – does not mean that son preference or sex selection are absent. Abortions for sex selection may occur even though access to abortion is legally restricted, as seen in Pakistan and Afghanistan. Sex selection may not involve abortion at all, as in the use of peri-conception techniques such as sperm sorting. Indigenous methods to ensure a male birth, whether effective or not, are also widely available and used across Asia.Citation5Citation7 Where fertility decline is not yet manifest or abortion less accessible, son preference may influence reproductive behaviour and contraceptive use.Citation16

Balancing sex ratios

Approaches that have been tried for re-balancing sex ratios include banning sex detection tests, restricting access to sex selective abortions and transforming the conditions that cause son preference. These approaches often exist in tandem.

Restricting sex determination tests

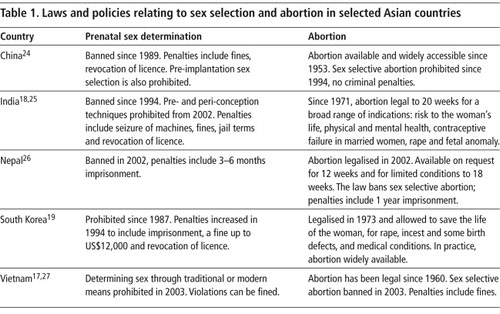

Starting with South Korea in 1987, several countries in Asia banned prenatal sex detection (see Table 1). Controls are similar in most countries and include limiting ultrasound use to authorised clinics, imposing reporting requirements on procedures done and making it illegal to reveal fetal sex. In Viet Nam, disseminating materials on sex selection can incur a fine, and in India, all diagnostic clinics need to have visible signage stating that sex detection tests are not performed. Sale of ultrasound machines is allowed only to registered health facilities.Citation17Citation18

Despite these controls, the availability of ultrasound has increased in all of these countries. The low cost of the technology for the provider and the woman and growing commercialisation and commodification of services in the unregulated private sector (which is large in India and burgeoning in Viet Nam and China), have fuelled an already high demand for prenatal sex detection.Citation8,10,19 In India, numerous “mobile clinics” using cheap portable ultrasound machines and run by unqualified persons (ranging from pharmacy assistants to local village practitioners) have mushroomed across towns and larger villages in the states where sex selection is common.Citation20 While control has been easier in the public sector, poor salaries for public sector doctors, underfunding of public hospitals and the dependence on user fees (Viet Nam and China) have led to some public sector providers and clinics offering these services as well.Citation8

As the sex of the fetus is usually revealed by verbal cues and nonverbal gestures and without leaving a paper trail, it is hard to prove.Citation5,21 Crackdowns to confiscate equipment from or shut down illegal clinics are common but few providers are caught actually doing a sex detection test. Where criminal penalties exist, it can take years to get a conviction. In India, over 400 cases have been registered since the ban was passed in 1994, of which nearly 90% are related to registration and record-keeping offences.Citation22 Under pressure to catch offenders, authorities often resort to unusual methods like monetary incentives to encourage “informants”. In India, sting operations where decoy patients visit clinics while a hidden camera captures the interaction are becoming increasingly common.

Nevertheless, there is no clear correlation between ultrasound availability and its use for sex selection. For example, ultrasound availability and use is higher in South India than in the north but sex ratios are more balanced in the south.Citation11 Routine overuse of ultrasound in pregnancy is also increasingly common; one study in Viet Nam found that on an average, women undergo 6–7 scans, but these are primarily “to check the baby was OK”.Citation23 Overall, as an analysis of the National Family Health Survey showed in India, the majority of women who have an ultrasound in pregnancy do not appear to be using it for sex selection.Citation11 All of this makes it hard to separate legal and illegal use and makes controls difficult to implement.

Restricting abortions for sex selection

Because a sex detection test is hard to pinpoint and because tests which do not result in a subsequent abortion, though illegal, do not affect sex ratios, the focus often shifts to the abortions that follow sex detection. Sex selective abortions are banned in several Asian countries that permit abortion on other grounds (see Table 1).

Proving that a particular abortion is sex selective is as difficult as proving that an ultrasound test is for sex determination, however. Typically, the ultrasound and abortion are done at separate clinics, making it difficult to establish a link between them.Citation21 Women sometimes use public clinics to have an abortion after having had a sex detection scan at a private hospital. Where reporting requirements exist, women give or doctors record reasons that fit within the legal framework.Citation5,21,28 On the one hand, this makes it possible for an unethical nexus between ultrasound clinics and abortion providers to flourish; on the other, it makes every doctor doing a second trimester abortion a possible (even if inadvertent) provider of a sex selective abortion.

All of this puts tremendous pressure on individual providers as well as health systems and governments to monitor, control and often restrict all second trimester abortions.

In 2004, the city of Guiyang in China introduced severe restrictions on abortions after 14 weeks; several other provinces followed. Women who are beyond 14 weeks now need a special letter of authorisation from local authorities before they can get an abortion.Citation29 The Indian government considered (but rejected) reducing the legal abortion time limit from 20 to 12 weeks.Citation25 Nevertheless, it is common to hear of providers self-restricting their practices to the first trimester in order to ensure that they cannot in any way be accused of providing sex selective abortions.Citation28 As with sex detection tests, the use of sting operations by NGOs and government authorities is becoming common. One state in India considered making it mandatory for clinics to report fetal sex in every second trimester abortion.Citation25 One district in India implemented a programme of monitoring and tracking every pregnancy, and this was also considered on a nationwide scale. Monitoring of pregnancies is already commonplace in China. Fears of medical abortion being used for clandestine second trimester abortions for sex selection, have resulted in several provinces in China banning the sale of medical abortion pills.Citation30 There are anecdotal reports in India of state governments trying to make the availability of abortion pills and drugs like ethacridine lactate more difficult as a way to restrict second trimester abortions (Sharad Iyengar, Action Research Training for Health, Personal communication, July 2008).

In practice, the way policies are interpreted and how the media depicts the issues diffuse the focus even further and foster an anti-abortion climate – best documented in the case of India.

Fostering an anti-abortion climate in India

Even 37 years after the passing of the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, awareness about when and in what circumstances abortion is legal remains poor in India.Citation31–33 Yet certain civil society groups, the media and government have actively promoted awareness of the ban on sex determination. Thus, not only is awareness of the ban high, but it is often misunderstood by both women and providers to be a ban on all abortions, whatever the reason.Citation28Citation34

While media coverage and informational materials on sex selection outnumber those on unsafe abortion, the former often contain inaccurate information or are ambiguous about the nature of behaviour change expected from their audience. The legality of abortion for other reasons is never mentioned and many materials give the impression that abortion for sex selection is the only type of abortion that exists.Citation35Citation36 Many also personify the fetus and commonly use the term “female feticide” (“female” is also often dropped), as are language and images that convey blood, murder and killing. The concept of sex selective abortion as a sin or immoral is also often used. Because of lack of appropriate terms, local language translations of these ideas sound even more anti-abortion than in English. Television and print media frequently carry reports and images of well-formed fetuses (usually female) found abandoned in wells, lakes and drains. Many of these are in fact stillbirths (six months or beyond), well beyond the gestational limits for which abortion is legally permitted, which adds to the complexity of the issue.

Language personifying the fetus was first used by activists and women's groups in India in order to gain attention and support for their cause, without any thought to the potential for anti-abortion ramifications.Citation37 However, the end result has been a vast proliferation of messaging that is anti-abortion and also an opportunity for those opposed to abortion rights to use sex selection as a front to promote anti-choice messages.

Fundamentalist religious leaders of all faiths are now increasingly lending their voices to the sex selection campaign and are also vocal about their anti-abortion stance. In 2005, UNFPA organised a conference of high-ranking leaders of all Indian faiths; most condemned sex selective abortion as being akin to murder, and strong sentiments against abortion per se were also expressed.Citation38 The government as well as several UN agencies endorsed an “anti-feticide” march of over 200 religious leaders across five states of the country. Some UN agencies working in the region also use the language of “feticide”, and some oppose sex selection as the right of unborn girls to be born. However, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other treaties clearly state that human rights begin at birth.Citation39

Why a focus on restricting abortion is problematic

As with ultrasound use, not all unwanted pregnancies are for sex selection. Data on the actual numbers of sex selective abortions or their proportion relative to abortions for other reasons is limited and often derived from extrapolations of sex ratio figures. However, several community-based studies in West India found that 2.5–17% of abortions among married women may be related to sex selection.Citation21,31,32 In a survey in rural China, 36% of married women acknowledged their abortions to be sex selective.Citation12 Data from the National Family Health and Welfare Survey in India suggest that about 8% of abortions may be related to sex selection.Citation40 While the illegality and negative publicity makes under-reporting possible, most unwanted pregnancies even among married women are aborted for other reasons.

While access to safe abortion is widely available in East Asia, the situation is different in India. Despite a policy that allows for abortion on a broad range of medical and social grounds, access to safe services is limited, there are vast rural–urban and geographic discrepancies, and morbidity from unsafe abortion is still a serious problem. In both contexts however, access to safe second trimester abortion remains problematic. Delays push abortions into the second trimester for many reasons unrelated to sex selection; late abortion seekers are more likely to be unmarried, young, poor, rural and less educated.Citation6,29,41 Restrictions further marginalise these already vulnerable women, increase costs, restrict the provider base and increase the potential for exploitation. On the other hand, women having a second trimester abortion for sex selection are more likely to come from economically better-off families and have more education and access to services.Citation21Citation28 It is likely that they will manage to access sex selection technologies clandestinely despite legal restrictions.

Addressing the root causes

More recently, attempts have also been made to address issues related to son preference in addition to controlling sex detection and/or sex selective abortions. The “Care for Girls” campaign in China, piloted in 2003, is now being scaled up nationally and includes positive messaging about girls, incentives to parents of daughters and encouragment of matrilineal marriages. Rural parents with daughters receive housing and pension payments after they reach sixty.Citation42 India too has several incentive schemes for parents who keep girls in school and unmarried till they reach 18 years. More controversial are schemes like the “cradle baby” scheme where parents can abandon unwanted girls to State-run orphanages to avoid a sex selective abortion. However, this may reinforce the concept of girls as an economic burden.

What works and what does not

Strategies to rebalance sex ratios have rarely been formally evaluated. A positive example of what works may come from the experience of South Korea, where grossly imbalanced sex ratios have gradually begun to return towards normal. Social and economic change, including a shift away from a farm-based economy and increases in nuclear families, urbanisation, greater workforce participation of women with better employment opportunities, more education of women and parents having retirement savings for old age security, have all been contributory factors. Several laws, such as one that allows women rights and responsibilities within the natal family even after marriage, and another allowing women-headed households were seen to be beneficial. A “Love your Daughters” media campaign also helped. South Korea, with its more controlled health system was also able to regulate sex determination tests more effectively.Citation9,15

An indication that methods based on fear and control may not have a long-term effect may come from the emerging example of Nawanshahr district in Punjab, India. In response to a particularly imbalanced sex ratio, local authorities launched a vigorous campaign in 2005 to register personal details of all pregnant women in an electronic database. The women were followed up with weekly telephone calls from three months of pregnancy to after birth. The district collector said in a press interview that “Every few days someone calls up the expectant mother to ask about her well-being. She knows she's being watched.” Every scan and abortion was investigated and there was also vigilant monitoring of ultrasound clinics. Monetary incentives were paid to community members to act as “informers”. The local NGO created awareness by publicly shaming families who had or were considering sex selection; they held “condolence meetings” and “death rites” to mourn the death of “girls killed in the womb”. The imbalanced ratio began to correct itself and the model was hailed as one to be replicated. However, with changes in the district authorities in 2007 and ending of the pregnancy monitoring and related schemes, sex ratio imbalances have reappeared.Citation22,43–45 Whether such intrusion into women's lives is ethical remains an issue, whether it succeeds or not.

A ban on sex detection tests does have a place but the successful implementation of this depends largely on self-regulation by individual providers and the commitment to medical ethics and vigilance exercised by medical professional bodies. To bring about increased accountability within the medical profession is also important; however, the unregulated growth of the private sector, commercialisation and corruption are issues that plague the health system as a whole and are not specific to the issue of sex detection or sex selective abortion.

It is also important to remember that even if it were possible to achieve control over ultrasound for sex detection, technology is ever changing, and any gains made would be lost if sex detection by another technique came into existence. Just as amniocentesis was replaced in large part by ultrasound, a finger-prick blood test that detects fetal cells circulating in maternal blood as early as 6–7 weeks of pregnancy has already become available.Citation46 The blood sample can be taken at home and mailed to a laboratory. Expensive for now, it is only a matter of time before demand and entrepreneurship make this and similar tests more widely available. It will be practically impossible to completely control or regulate such tests, despite the most stringent laws. Similarly, it is possible that pre-conception techniques may become more affordable or reliable, and these do not even involve an abortion.

The way forward: keeping the focus where it belongs

Keeping women centre stage

The conflict between individual decisions which lead to collective social injustice (imbalanced sex ratios) is not an easy ethical dilemma to resolve. Nevertheless, the complex conditions under which women make the “choice” to have a sex detection test or sex selective abortion need to be understood. Women themselves acquire patriarchal biases. They may be under direct pressure from families or may fear violence or the husband abandoning them for a new wife should they not produce a son.Citation12,21,28 Sometimes, women who have an unwanted pregnancy to start with are pressured by family or doctors to have sex detection and confirm that they are not “wasting a male”. They may come from economically well-off families but their autonomy and decision-making powers and control over money are often limited.Citation21 For the individual woman faced with these dilemmas, her choices may represent a way to mitigate her circumstances and paradoxically raise her status within the family and society in the short term, or provide her with an option in the face of coercive state controls.Citation47

Some laws, like the Indian one, recognise that a woman may not be acting out of free choice when she has a sex detection test, and she is legally presumed to be innocent unless proven otherwise. However, freedom from legal sanctions does not protect her from social and familial consequences. The discrimination or violence faced by women who are unable to meet the demand for sons needs to be documented and to inform the debate.

Concerns about increasing sex ratio imbalances are often expressed in terms of the shortage of brides (marriage squeeze) and sexual partners for men, the resultant increase in violence against women, migration and trafficking, and security threats in the wake of large numbers of single, potentially violent men.Citation22Citation48 All of these concerns seem to reduce men to sexual predators, commodify women, and miss the essential crux of inequality, which is not about unequal numbers but about unequal power structures and gender relations.

Addressing these root elements of discrimination, e.g. ensuring the effective implementation of existing policies that foster gender equality, such as anti-dowry laws in India, is important. It is also important to lobby for other proactive measures such as equal opportunities in education, employment and inheritance, and introducing pension and social security schemes that will foster independence in old age.Citation3,10 Directive family planning polices and targeted approaches that have exacerbated son preference need to be discarded. They should not be replaced by new “targeted” approaches (for example, China has set a target of normalising the sex ratio by 2016) as these can only be counter-productive.

Ensuring access to safe and legal abortion

Unsafe abortion remains a significant problem in several parts of Asia and particularly in India, and the increasing anti-abortion climate enhances the risk of losing the gains made in making abortion safe by the Indian government and other groups in recent years. Best documented in India, anti-abortion activity is gaining ground in other parts of the Asian region as well. At the same time, few gains have been made towards normalisation of sex ratios. Activists and advocates working on sex selection and those working on ensuring access to safe abortion usually work in isolation from one another and have only a limited understanding of the complex intersections between the two issues.

Though the government remains committed to keep the two issues separate, on the ground the realities are different. However, steps can be taken to start disentangling the issue of safe and legal abortion from that of illegal sex selection. Ensuring that messaging does not use the language and imagery of “feticide” or personify the fetus in other ways, and that both sex selection and safe abortion messages give an accurate and balanced picture of both issues and the laws of the country concerned, are necessary first steps. A better understanding by the media of the two issues is also needed. Better and more accurate data on unsafe abortion, second trimester abortion and sex selective abortion, and the linkages between them, is important as well.

Correcting the imbalances in the sex ratio at birth is a complex issue without easy answers. While the use of prenatal technology and selective abortions is the pathway through which son preference results in an imbalanced sex ratio, normalisation of sex ratios cannot be achieved by controlling either the technology or abortions, as neither of them are the root causes. There are indications that son preference may already be on the decline, especially among younger women.Citation10 This secular trend may be reflected in sex ratio changes over time. This process can be accelerated if strategies are focused on countering the gender inequality that drives son preference. This is the only sustainable way to reduce sex selection.

Acknowledgments

This paper builds on a presentation at a meeting of the National Campaign for Safe Abortion in Mumbai, April 2008. The author is grateful to Traci Baird for comments on earlier drafts.

Notes

* India does not use this international convention; the normal sex ratio of 104–107 would be referred to in Indian literature as 934–961 girls to 1000 boys.

References

- P Visaria. The sex ratio of the population of India and Pakistan and regional variations during 1901–61. A Bose. Patterns of population change in India 1951–61. 1967; Allied Publishers. 334–371.

- United Nations. World population prospects: the 2006 revision. At: <http://data.un.org/Data.aspx?d=PopDiv&f=variableID%3a52. >. Accessed 2 May 2008.

- J Banister. Shortage of girls in China today. Journal of Population Research. 2004. At: <http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0PCG/is_1_21/ai_n6155263/pg_1?tag=artBody;col1. >. Accessed 14 March 2008.

- Registrar General of India. Primary census abstract, India. Census of India 2001. New Delhi: Government of India.

- Institute for Social Development Studies. New “common sense”: family planning policy and sex ratio in Viet Nam. UNFPA, 2007. At: <www.unfpa.org/gender/docs/studies/Vietnam.pdf. >. Accessed 16 February 2008.

- D Belanger, K Oanh, L Jianye. Are sex ratios at birth increasing in Vietnam. Population (E). 58(2): 2003; 231–250.

- CREHPA. Sex selection: pervasiveness and preparedness in Nepal. UNFPA, 2007. At: <www.unfpa.org/gender/docs/studies/nepal.pdf. >. Accessed 26 March 2008.

- Z Wu, K Viisainen, E Hemminki. Determinants of high sex ratio among newborns: a cohort study from rural Anhui province, China. Reproductive Health Matters. 14(27): 2006; 172–180.

- D Kim. Missing girls in South Korea: trends, levels and regional variations. Population (E). 59: 2004; 865–878.

- T Hesketh, Li Lu, Z Xing. The effect of China's one-child family policy after 25 years. New England Journal of Medicine. 353: 2005; 1171–1176.

- PNM Bhat, AJF Zavier. Factors influencing the use of prenatal diagnostic techniques and the sex ratio at birth in India. Economic and Political Weekly. 16 June: 2007; 2292–2303.

- C Junhong. Prenatal sex determination and sex selective abortion in central China. Population and Development Review. 27(2): 2001; 259–280.

- D Almond, L Edlund. Son-biased sex ratios in the 2000 United States census. The National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2008. At: www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.0800703105. Accessed April 24, 2008.

- S Dubuc, D Coleman. An increase in the sex ratio of births to India-born mothers in England and Wales: Evidence for sex-selective abortion. Population and Development Review. 332): 2007; 383–400.

- W Chung, M Das Gupta. The decline of son preference in South Korea: the roles of development and public policy. Population and Development Review. 33(4): 2007; 757–783.

- T Leone, Z Matthews, G Zuanna. Impact and determinants of sex preference in Nepal. International Family Planning Perspectives. 29(2): 2003; 69–75. At: <www.guttmacher.org/pubs/journals/2906903.html. >. Accessed 23 January 2008.

- Government of Viet Nam. Decree 104/2003/ND-CP. Detailing and guiding the implementation of a number of articles of the population ordinance. Hanoi, 2003.

- Ministry of Law and Justice. The Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (Regulation and Prevention of Misuse) Amendment Act. 2002; Government of India: New Delhi.

- A Villa. Sex preferences and fertility trends in South Korea. Asia-Pacific Social Science Review. 6(2): 2006; 153–161.

- Unisa S, Pujari S, Ram U. Sex selective abortion in Haryana: evidence from pregnancy history and antenatal care. Economic and Political Weekly 2007;6 January;60–66.

- B Ganatra, S Hirve, V Rao. Sex-selective abortion: evidence from a community based study in western India. Asia-Pacific Population Journal. 16(2): 2001; 109–124.

- C Guilmoto. Characteristics of sex ratio imbalance in India and future scenarios. 2007; UNFPA.

- T Gammeltoft, H Nguyen. The commodification of obstetric ultrasound screening in Hanoi, Viet Nam. Reproductive Health Matters. 15(29): 2007; 163–171.

- State Family Planning Commission of China. Population and Family Planning Law of the People's Republic of China. 2002; China Population Publishing House: Beijing.

- S Hirve. Abortion law, policy and services in India: a critical review. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24 Suppl): 2004; 114–121.

- S Thapa. Abortion law in Nepal: the road to reform. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24 Suppl): 2004; 85–94.

- Government cracks down on abortion practice. Viet Nam News. 17 October. 2006

- Visaria, L, Ramachandran V, Ganatra B, et al. Abortion in India: emerging issues from qualitative studies. Economic and Political Weekly 2004;24 November:5044–52.

- Xinhua. Guiyang to ban abortion after 14 weeks. China Daily. 16 December. 2004

- Xinhua. Henan bans gender selective abortions. China Daily. 3 January. 2007

- B Elul, S Barge, S Verma. Unwanted pregnancy and induced abortion: data from men and women in Rajasthan, India. 2004; Population Council: New Delhi, 29–30.

- Malhotra A, Nyblade L, Parasuraman S, et al. Abortion and contraception in India. New Delhi: International Centre for Research on Women, 2003. p.19/28–29.

- B Ganatra, S Hirve. Induced abortions among adolescent women in rural Maharashtra, India. Reproductive Health Matters. 10(19): 2002; 76–85.

- I Jaising, C Sathyamala, A Basu. From the abnormal to the normal: preventing sex selective abortions through the law. 2007; Lawyers Collective: New Delhi, 87–88.

- V Nidadavolu, H Bracken. Abortion and sex determination: conflicting messages in information materials in a district of Rajasthan, India. Reproductive Health Matters. 14(27): 2006; 160–171.

- F Naqvi. Images and icons: harnessing the power of mass media to promote gender equality and reduce practices of sex selection. 2006; BBC World Service Trust: New Delhi.

- M Gupte. A walk down memory lane: an insider's reflections on the campaign against sex selective abortions. 2003; MASUM: Pune. At: <http://geneticsandsociety.org/downloads/200308_gupte.pdf. >.

- R Bhagat. Turning to faith to find the missing daughters. Hindu Business Line. 14 November. 2005

- R Copelon, C Zampas, E Brusie. Human rights begin at birth: international law and the claim of fetal rights. Reproductive Health Matters. 13(26): 2005; 120–129.

- F Arnold, S Kishore. Sex selective abortions in India. Population and Development Review. 28(4): 2002; 759–785.

- M Gallo, N Nghia. Real life is different: a qualitative study of why women delay abortion until the second trimester in Vietnam. Social Science and Medicine. 64: 2007; 1812–1822.

- Xinhua. China promotes girls to avoid glut of bachelors. China Daily. 8 August. 2006

- A Soondas. Girls uninterrupted in Nawanshahr. Times of India. 10 February. 2007

- V Sareen. Sorry, sex ratio dips again in Nawanshahr. Punjab Newsline. 3 July. 2008

- Chaba A. Fall from grace: declining sex ratio in Nawanshahr district. 27 April 2008.

- CC Ren, XH Miao, H Cheng. Detection of fetal sex in the peripheral blood of pregnant women. Fetal Diagnosis and Therapy. 22(5): 2007; 377–382.

- R Varma. Technological fix: sex determination in India. Bulletin of Science, Technology and Society. 22(1): 2002; 21–30.

- A Den Boer, V Hudson. The security threat of Asia's sex ratios. SAIS Review. 24(2): 2004; 27–43.