Abstract

In Africa, a large proportion of HIV infections occur within stable relationships, either because of prior infection of one of the partners or because of infidelity. In five African countries at least two-thirds of couples with at least one HIV-positive partner were HIV serodiscordant; in half of them, the woman was the HIV-positive partner. Hence, there is an urgent need to define strategies to prevent HIV transmission within couple relationships. HIV counselling and testing have largely been organised on an individual and sex-specific basis, for pregnant women in programmes for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and in STI consultations and recently male circumcision for men. A couple-centred approach to HIV counselling and testing would facilitate communication about HIV status and adoption of preventive behaviours within couples. This paper reviews what is known about HIV serodiscordance in heterosexual couples in sub-Saharan Africa and what has been published about couple-centred initiatives for HIV counselling and testing since the early 1990s. Despite positive outcomes, couple-oriented programmes have not been implemented on a large scale. In order to stimulate and strengthen HIV prevention efforts, increased attention is required to promote prevention and testing and counselling for couples in stable relationships.

Résumé

En Afrique, une forte proportion d’infections à VIH se produit dans des relations stables, soit en raison d’une infection antérieure ou de l’infidélité de l’un des partenaires. Dans cinq pays africains, au moins les deux tiers des couples dont un des partenaires au moins est séropositif étaient sérodiscordants ; dans la moitié, c’était la femme qui était porteuse du virus. Il est donc urgent de définir des stratégies pour lutter contre la transmission du VIH dans les couples. En général, le conseil et le dépistage du VIH ont été organisés individuellement et selon les sexes, pour les femmes enceintes dans des programmes de prévention de la transmission mère-enfant du VIH, dans des consultations d’IST et récemment à l’occasion de la circoncision pour les hommes. Centrer le conseil et le dépistage du VIH sur le couple faciliterait la communication sur le statut sérologique et l’adoption de comportements préventifs. Cet article examine les connaissances sur la sérodiscordance dans les couples hétérosexuels en Afrique subsaharienne et les publications sur les initiatives de conseil et de dépistage du virus axées sur le couple depuis le début des années 90. En dépit de résultats positifs, les programmes destinés aux couples n’ont pas été appliqués à une grande échelle. Afin de stimuler et de renforcer les activités de prévention du VIH, il faut s’employer davantage à promouvoir la prévention ainsi que le dépistage et le conseil pour les couples stables.

Resumen

En Ãfrica, una gran proporción de infecciones por VIH ocurren en relaciones estables, ya sea por infección anterior de una de las parejas o por infidelidad. En cinco países africanos, por lo menos dos terceras partes de las parejas con uno o dos miembros VIH-positivos, eran VIH serodiscordantes; en la mitad, la mujer era VIH-positiva. Por tanto, existe una necesidad urgente de definir estrategias para evitar la transmisión del VIH entre parejas. La consejería y pruebas de VIH han sido organizadas de manera individual y específica al sexo, para mujeres embarazadas en programas para la prevención de la transmisión materno-infantil del VIH, en consultas sobre las ITS y, recientemente, durante la circuncisión masculina. Un enfoque centrado en la pareja facilitaría la comunicación sobre el estado del VIH y la adopción de comportamientos preventivos. En este artículo se revisan los conocimientos de la serodiscordancia de VIH en parejas heterosexuales de Ãfrica subsahariana y publicaciones sobre las iniciativas de consejería y pruebas de VIH centradas en parejas desde principios de la década de los noventa. Pese a resultados positivos, no se han implementados programas en gran escala. A fin de estimular y fortalecer los esfuerzos para la prevención del VIH, es imperativo prestar más atención para promover la prevención, consejería y pruebas del VIH en parejas en relaciones estables.

Although access to antiretroviral treatment is increasing worldwide, the need to reinforce HIV prevention efforts has never been stronger. In sub-Saharan Africa, 1.7 million people were newly infected in 2007,Citation1 highlighting the world’s failure to slow the spread of the epidemic, and the need to implement and scale-up efficient strategies for HIV prevention, and find new prevention approaches.Citation2 Since the beginning of the epidemic in Africa, HIV prevention campaigns and messages have mainly been focused on the prevention of “at risk” sexual behaviours, involving professional sex workers and occasional partners. Yet many studies have shown that a large proportion of HIV infections occur within stable relationships, either because of prior infection of one of the partners or because of infidelity.Citation3–5 It has also been assumed that it is more difficult to adopt preventive behaviours with a regular partner than with an occasional partner, and the difficulties women face to have protected sex in a marital relationship have been described.Citation6Citation7 Recent studies show that it may also be difficult for men to negotiate protection within the couple too.Citation8Citation9

Many men and women who live in a relationship with an HIV-positive partner do not know their own HIV status. However, HIV serodiscordancy in heterosexual couples is highly prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa,Citation10 and there is an urgent need to find feasible and acceptable strategies to promote HIV prevention within these relationships. This paper focuses on HIV prevention issues within serodiscordant heterosexual couples in sub-Saharan Africa and couple-centred approaches to HIV counselling and testing.

Methodology

We reviewed the published scientific literature addressing couple-oriented HIV counselling and testing, from the early 1990s to May 2008. We focus on sub-Saharan Africa, where HIV transmission is mainly heterosexual. We consulted databases Medline and Scopus for peer-reviewed papers, using the search terms “HIV infections”, “counselling” or “counseling”, “couple” or “couples”, and “Africa”.

The need for a focus on couples in HIV prevention

HIV serodiscordance within couples: new data

It has long been demonstrated that HIV transmission occurs within stable couples.Citation4,5,13Footnote* In Zambia, DNA sequencing found that 87% of new HIV infections among negative individuals living in a serodiscordant couple were acquired from the spouse.Citation14 Until recently, most of the studies following up HIV-negative or HIV serodiscordant couples in countries with generalised HIV epidemics tended to show that women were at especially high risk of HIV infection from within their regular partnership, presumably due to their higher biological susceptibility and the infidelity of the men. These data were reinforced by individual representations: women feared being infected by their spouse/regular partner, whereas men feared HIV infection from “outside” partners.Citation15

Recent large-scale studies have shed new light on these matters. The latest Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) have been collecting HIV-related data, and it is now possible to assess the HIV status of cohabiting couples at country level. Data from Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya and Tanzania have revealed that at least two-thirds of couples in each country with at least one HIV-positive partner were HIV serodiscordant. In half the serodiscordant couples, the woman was HIV-positive and the man HIV-negative.Citation10 This may partly be explained by women getting HIV-infected during premarital sex. Indeed, in Africa a high proportion of young women are infected with HIV in their teens, before marriage, because they engage in transactional relations with older men.Citation16 However De Walque’s analysis suggests that extramarital sexual activity among women in union, as among men in union, is also a substantial source of vulnerability to HIV infection.Citation10 A recent study in rural South Africa also showed that the direction of spread of the epidemic was not only from returning migrant men to their wives, but also from women to their migrant husbands.Citation17 More recently, among 8,500 cohabiting couples who sought couple HIV testing in Lusaka, Zambia between 1994 and 2000, it was found that nearly half were discordant, with HIV-positivity equally distributed between the men and the women.Citation3

These findings suggest the need to reconsider the assumption that HIV infection among cohabiting couples is due only to extramarital sexual activity by men, and the difficulties women encounter in protecting themselves. Obviously, this is a reality for many women, but men are also at high risk of HIV infection as regular partners in countries heavily affected by the epidemic. Hence, it is not sufficient to promote fidelity to the regular partner and preventive behaviours only for occasional or transactional sex.

The prevention of HIV transmission within serodiscordant couples must become a key strategy for HIV prevention. This is rarely a priority in prevention efforts, as such couples are not among the “key populations” to whom prevention programmes are to be targeted. Things may be changing, however; in 2006, PEPFAR added couple counselling to its priorities for voluntary counselling and testing.Citation18

Informing couples about HIV serodiscordancy

The lack of HIV prevention aimed at couples partly comes from misperceptions of the extent of HIV serodiscordancy and denial that it is possible. In Uganda,Citation19 for example, partners reported:

“I have failed to understand how discordance is possible, and up to now I have never believed that I am HIV negative when my partner is positive.”

“If all along I was not infected, how will I get infected now?”

A study in Côte d’Ivoire among HIV-negative women found that their male partners did not seek HIV testing, even though it was offered free of charge, because they believed their serostatus was necessarily the same as their wife’s.Citation20 If both partners believe they must have the same HIV serostatus, they will usually not see why they should use protection during sex.

Condom use therefore remains low in the conjugal context.Citation10Citation21 Condom use is frequently associated with occasional partners and suggesting condom use to a regular partner often interpreted as proof of infidelity.Citation8,22 Nevertheless, recent encouraging findings from South Africa are that women appear to be less powerless at negotiating condom use than is frequently reported and do manage to use condoms when they perceive themselves at risk of HIV infection.Citation9 Further, in a study among married couples in Uganda, attitudes towards condoms have changed over the past decade, in particular, men appear to be less negative than previously assumed about condom use in a conjugal context.Citation23 The dual protective nature of condoms is a strong argument to use with a regular partner: condoms not only as a protection from HIV and other STIs but also as a family planning method. This appears to be more acceptable in stable couples, since it does not imply distrust.Citation23–25

Condom use is also greater within couples where there is dialogue on sexual risks.Citation26Citation27 The few studies on this subject underline the crucial need to provide men and women with information, support and condom supplies, to sustain long-term conjugal condom use. In the absence of continuous support, although condom use increases in the immediate period after counselling, it gradually decreases again. In Abidjan, where fewer than 10% of stable couples used condoms on a regular basis, 28% of women tested and counselled on HIV during pregnancy used condoms with their regular partner when they resumed sexual activity after delivery. Two years after delivery, however, condom use with regular partners had fallen back to the national average.Citation28

HIV counselling and testing usually sex-specific

HIV counselling and testing, the first step in effective HIV prevention, are largely organised as individual and sex-specific services. For a long time, most HIV testing opportunities were for pregnant women only, for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT). Even now, in most of these programmes, it is still generally the woman who decides whether to disclose her test result to her partner, and through her that male partners are informed about HIV and PMTCT. In Africa, where coverage of PMTCT is insufficient and coverage of voluntary HIV counselling and testing for the general population remains even lower, the proportion of men tested for HIV is very small. Thus, women who discover their HIV infection during pregnancy are often the first member of the couple to be aware of their status and to receive HIV counselling.

Within PMTCT programmes, the lack of information provided to the male partner has proven to be most constraining. Some pregnant women refuse HIV testing without their partner’s approval,Citation29 and it seems that the recently promoted “opt-out” approach to routine antenatal HIV testingCitation30 has not modified many women’s attitude.Citation31 Women also tend to refuse antiretroviral prophylaxis or infant formula because they fear the reaction of their husband, when he realises they have taken health decisions without discussing them with him.Citation32 Finally, it is difficult for a pregnant woman who knows she has HIV to have protected intercourse with her spouse if he is unaware of her serostatus. Condom use with regular partners is very low after antenatal HIV testing,Citation33, and only increases when the partner has been notified of his wife’s HIV-positive statusCitation27 or has been tested himself.Citation34 A recent study in Abidjan has shown that, for all these reasons, HIV-positive women tended to inform their partner of their HIV status before opting for formula feeding for the baby, and when sexual activity was resumed.Citation35

For men, the main options for HIV testing have been within outpatient STI consultations or the rare anonymous and voluntary HIV counselling and testing centres. Male circumcision programmes are providing new opportunities.Citation36 The consequences, within the couple, of greater HIV testing among men will need to be thoroughly evaluated. Will men aware of their HIV status be able to suggest condom use to their conjugal partner and inform her of the HIV test result? HIV testing initiatives for men will need to ensure appropriate counselling of both men and women. Indeed, it was recently shown that women are not always the ones willing to use condoms. In KwaZulu Natal, 65% of rural women interviewed had a negative attitude towards condoms.Citation9

At the moment, HIV testing is usually proposed to men and women separately, and on very different occasions. This does not facilitate communication between them regarding HIV status. Yet this dialogue is critical for the adoption of preventive behaviours within the couple. An important strategy, then, is a couple-centred approach to HIV counselling and testing.

Couple-centred approaches to HIV counselling and testing

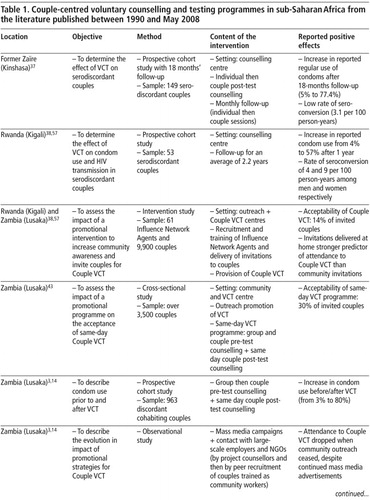

Couple-centred voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) initiatives were first developed during the 1990s. Papers on couple-centred HIV counselling and testing initiatives published to date come from Trinidad, former Zaire, Rwanda, Zambia, Tanzania and Kenya (Table 1). In the five African countries, adult HIV prevalence ranged from 3% to 17% in 2007.Citation1 The couple-centred VCT initiatives reported were organised in different ways. In the first published paper about such a programme, in former Zaire, couples were recruited after HIV diagnosis and provided with continuous individual and couple counselling for 18 months.Citation37 In Rwanda and Zambia, in programmes initiated by the same research group,Footnote* couples arriving at the VCT centre were offered group pre-test counselling in the morning, with a video and a group discussion on HIV (20 couples on average). Each couple then spoke privately with a counsellor and decided whether to be tested for HIV. Individual counselling was provided only on request, or if the counsellor felt it was necessary. On the same day, each couple received joint confidential post-test counselling.Citation3,14,38 In a multi-site couple VCT efficacy study in Kenya, Tanzania and Trinidad, the process was slightly different: when couples arrived for VCT at a health centre, the couple were counselled together or individually, by their own choice. Some individual time with a counsellor was given to ensure accurate risk assessment. Couples were informed before HIV testing that they were expected to share their test results. Test results were given two weeks later, individually first, and then partners were encouraged to share their results within a couple post-test counselling session.Citation39Citation40

Whatever the procedures adopted, all these programmes showed positive outcomes (Table 1). The rates of HIV status disclosure to partners were high. In the multi-site VCT study, disclosure rates were 91% among participants enrolled as couples vs. 70% among individuals.Citation40 In all other experiences reported, participants were enrolled as couples and couple post-test HIV counselling sessions were provided, so disclosure rates to the partner were 100%. An important result was that HIV status disclosure was rarely accompanied by a negative reaction from the partner. In Tanzania, less partner violence was reported among women who disclosed their serostatus to their partner compared to those who did not (10% vs 17%).Citation41 The consequences of disclosing HIV test results in the context of couple counselling were usually positive among both HIV-positive and HIV-negative men and among HIV-negative women, resulting in the strengthening of the sexual relationship.

The situation appeared to be more uncertain for HIV-positive women, however. In the multi-site study, serodiscordant couples with an HIV-positive woman were more likely to report the break-up of a marriage than other couples (20% vs 0.7%).Citation39Citation40 In settings without couple VCT, the break-up of the relationship among HIV-positive women has also been documented, but was not related to notification of the partner.Citation33Citation42 It is possible that these break-ups do not result from a negative reaction of the partner, but rather occur because the woman prefers to separate rather than face the difficulties of a conjugal relationship coping with HIV infection.

The couple VCT studies published to date have also reported on condom use with the regular partner. All programmes reported a dramatic impact of couple VCT, with condom use rates increasing from 5% to 77% in Kinshasa, 4% to 57% in Kigali, and 3% to 80% in Lusaka (Table 1\).

In spite of the positive outcomes of couple VCT programmes, the acceptability of these services remains low. In Zambia, in the early 1990s, the same-day VCT programme was acceptable to only 30% of invited couples,Citation43 and more recently, the acceptability of couple VCT was only 14% of invited couples.Citation38 One of the keys to improved acceptability and attendance at existing couple-oriented services seems to be the promotion of couple VCT. In Zambia, couple VCT was promoted via the media and by door-to-door outreach invitations by community workers: promotion messages mainly addressed the misconception that cohabiting couples always have the same HIV status, and emphasised the confidentiality of couple VCT services. But attendance at couple VCT dropped when community outreach ceased, despite continued media advertising.Citation3 The experiences in Rwanda and Zambia show that door-to-door promotion of couple VCT by well-trained and influential members of the community was needed to overcome the fear of stigma among couples.Citation38

Gathering of two families to discuss prospects and shortcomings of the bride and groom, Kakuma Refugee Camp, Kenya, 2001

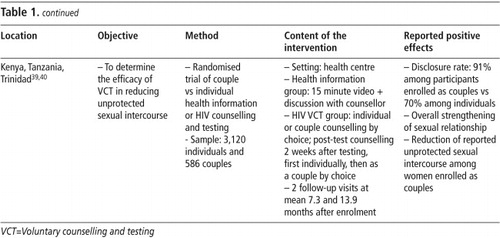

In addition to the couple VCT programmes described in the literature, two others were based in PMTCT programmes, one in Zambia and the other in Kenya (Table 2).Citation44Citation45 Both studies found very positive outcomes: couple counselling was associated with an increase in HIV testing acceptance, and in the uptake of antiretroviral prophylaxis and of formula feeding. In Zambia, there were no significant differences in reported adverse social events between couple-counselled versus individually-counselled women, but a trend towards a higher level of divorce or separation among serodiscordant couples was observed.Citation44

It is possible that couple-centred approaches may be desirable in certain conjugal contexts but not in all. The data are conflicting. Qualitative studies report cases of women who have been rejected by their male partner because they were HIV-positive,Citation52 while in quantitative studies, negative outcomes after disclosure are relatively rare.Citation53Citation54 The relationship between disclosure and violence may be biased, however: women who fear a negative reaction from their partner may avoid disclosing whereas women who expect a supportive reaction may disclose more easily. Large studies are needed to obtain representative, population-based data.

Discussion

In the early 2000s, UNAIDSCitation46 and othersCitation47 were advocating for couple-centred approaches to HIV prevention:

“Married couples should be encouraged to go for HIV counselling together so that serodiscordant couples can be identified and counselled… Offering VCT to couples overcomes the problem of sharing results… The majority of studies of couple counselling report successful outcomes.”Citation46

At the same time, studies of PMTCT, although not couple-centred, have also concluded that there was a need to “involve” male partners.Citation48Citation49

However, in spite of the available data and repeated recommendations, couple-centred approaches to HIV prevention (whether connected with PMTCT or prevention of sexual transmission) have not been implemented on a large scale or, at least, have not been documented in the literature, where others could learn from them. Apart from the experiences reported in Former ZaïreCitation37, Rwanda,Citation38Citation57, ZambiaCitation3,14,43,44, KenyaCitation45, and the multi-site study Kenya-Tanzania-TrinidadCitation39Citation40, it is hard to find in recent years any mention of a couple-centred approach in the scientific literature or in programmatic documents.Footnote* Even in the latest UNAIDS Global Report on HIV/AIDS, no mention is made of the potential of couple-centred approaches.Citation51

In order to further stimulate and strengthen HIV prevention efforts, increased attention is required to promote adequate prevention messages and services for couples. Pilot couple-oriented programmes have led to positive results but they were not scaled up or taken up by other countries. The approach could be implemented in existing HIV testing settings, which are traditionally sex-specific: antenatal care consultations and male circumcision programmes, for example. Additional research should also explore new means of communication for improving the image of condoms and promoting condom use as a conjugal practice.Citation14,47,55 New counselling tools focused on couples could also contribute to increasing condom use.Citation56 Finally, research on HIV risk management and prevention within couple relationships should be strengthened. In sub-Saharan Africa, there is still inadequate socio-behavioural knowledge of HIV prevention within the dynamics of couple relationships.Citation47 This includes couple communication on sexual risk; the evolution of preventive behaviours over time (e.g. by duration of relationship and time since VCT); and gender issues of negotiation and violence. This research needs to keep in mind that although the increased involvement of men within HIV prevention is urgently required, it should not be to the detriment of the rights and autonomy of women.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this paper entitled “Women facing HIV prevention within their couple: a question at a standstill?” was presented at the 8th AIDS Impact conference, Marseille, 1–4 July 2007. This is an expanded and updated version.

Notes

* The definition of a couple can range from formal marriage between cohabiting spouses, to a stable relationship without any formalisation of the union, and sometimes without cohabitation of the partners.Citation11Citation12 We include here the broader meaning of “regular relationship”, whatever the nature of the union. We consider heterosexual couples only, because male-male couples, who may also be at high risk of HIV serodiscordancy, require separate analysis.

* The Rwanda Zambia HIV Research Group, lead by Susan Allen, Emory University, Atlanta GA, USA.

* Both authors of this review paper are involved in an ongoing HIV intervention trial evaluating antenatal couple VCT in Cameroon, Georgia, India and Dominican Republic.Citation50

References

- UNAIDS. AIDS Epidemic update. December 2007. Geneva; 2007.

- RE Bunnell, JH Mermin, KM De Cock. HIV prevention for a threatened continent. Implementing positive prevention in Africa. Journal of American Medical Association. 296(7): 2006; 855–858.

- E Chomba, S Allen, W Kanweka. Evolution of couples’ voluntary counseling and testing for HIV in Lusaka, Zambia. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 47(1): 2008; 108–115.

- LM Carpenter, A Kamali, A Ruberantwari. Rates of HIV-1 transmission within marriage in rural Uganda in relation to the HIV sero-status of the partners. AIDS. 13: 1999; 1083–1089.

- S Malamba, JH Mermin, RE Bunnell. Couples at risk. HIV-1 concordance and discordance among sexual partners receiving voluntary counseling and testing in Uganda. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 39(5): 2005; 576–580.

- R Van Rossem, D Meekers, Z Zkinyemi. Consistent condom use with different types of partners: evidence from two Nigerian surveys. AIDS Education and Prevention. 13(3): 2001; 252–267.

- D Worth. Sexual decision-making and AIDS : why condom promotion among vulnerable women is likely to fail. Studies in Family Planning. 20(6): 1989; 297–307.

- AM Chimbiri. The condom is an ‘intruder’ in marriage: evidence from rural Malawi. Social Science and Medicine. 64(5): 2007; 1102–1115.

- P Maharaj, J Cleland. Risk perception and condom use among married or cohabiting couples in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. International Family Planning Perspectives. 31(1): 2005; 24–29.

- D De Walque. Serodiscordant couples in five African countries: implications for prevention strategies. Population and Development Review. 33(3): 2007; 501–523.

- D Meekers. The process of marriage in African societies: a multiple indicator approach. Population and Development Review. 18(1): 1992; 61–78.

- D Meekers, AE Calves. “Main” girlfriends, girlfriends, marriage, and money: the social context of HIV risk behaviour in sub-Saharan Africa. Health Transition Review. 7(Suppl): 1997; 361–375.

- S Hugonnet, F Mosha, J Todd. Incidence of HIV infection in stable sexual partnerships: a retrospective cohort study of 1802 couples in Mwanza Region, Tanzania. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 30(1): 2002; 73–80.

- S Allen, J Meinzen-Derr, M Kautzman. Sexual behavior of HIV discordant couples after HIV counseling and testing. AIDS. 17(5): 2003; 733–740.

- KP Smith, SC Watkins. Perceptions of risk and strategies for prevention: responses to HIV/AIDS in rural Malawi. Social Science and Medicine. 60: 2005; 649–660.

- E Pisani. AIDS into the 21st century: some critical considerations. Reproductive Health Matters. 8(15): 2000; 63–76.

- M Lurie, J Williams, K Zuma. Who infects whom? HIV-1 concordance and discordance among migrant and non-migrant couples in South Africa. AIDS. 17: 2003; 2245–2252.

- PEPFAR. The Emergency Plan’s Priorities for HIV Counseling and Testing. 2007

- RE Bunnell, J Nassozi, E Marum. Living with discordance: knowledge, challenges, and prevention strategies of HIV-discordant couples in Uganda. AIDS Care. 17(8): 2005; 999–1012.

- H Brou, H Agbo, A Desgrées du Loû. [Impact of HIV counselling and testing during antenal consultation for HIV-women in Abidjan (Côte d’Ivoire): a quantitative and qualitative study (Ditrame Plus 3 project, ANRS 1253)]. Santé. 15(2): 2005; 81–91.

- United Nations. Levels and trends of contraceptive use as assessed in 2000. 2002; UN: New York.

- EK Bauni, BO Jarabi. The low acceptability and use of condoms within marriage: evidence from Nakuru district, Kenya. Etude de la Population Africaine / African Population Studies. 18(1): 2003; 51–65.

- NE Williamson, J Liku, K McLoughlin. A qualitative study of condom use among married couples in Kampala, Uganda. Reproductive Health Matters. 14(28): 2006; 89–98.

- J Cleland, MM Ali. Sexual abstinence, contraception, and condom use by young African women: a secondary analysis of survey data. Lancet. 368: 2006; 1788–1793.

- J Cleland, MM Ali, I Shah. Trends in protective behaviour among single versus married young women in sub-Saharan Africa: the big picture. Reproductive Health Matters. 14(28): 2006; 17–22.

- B Zamboni, I Crawford, P Williams. Examining communication and assertiveness as predictors of condom use: implications for HIV prevention. AIDS Education and Prevention. 12: 2000; 492–504.

- A Desgrées-du-Loû, H Brou, G Djohan. Beneficial effects of offering prenatal HIV counselling and testing on developing a HIV preventive attitude among couples. Abidjan, 2002–2005. Aids and Behavior. 2007(Online first. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9316-6.)

- H Brou, G Djohan, R Becquet. Sexual prevention of HIV within the couple after prenatal HIV-testing in West Africa. Aids Care. 20(4): 2008; 413–418.

- A Desgrées du Loû, H Brou, G Djohan. Le refus du dépistage prénatal: une étude de cas à Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. [Refusal of prenatal HIV-testing: a case study in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire]. Santé. 17(3): 2007; 133–141.

- World Health Organisation/UNAIDS. Guidance on provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling in health facilities. 2007; WHO: Geneva.

- J Homsy, R King, S Malamba. The need for partner consent is a main reason for opting out of routine HIV testing for prevention of mother-to-child transmission in a rural Ugandan hospital. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 44(3): 2007; 366–369.

- J Kiarie, J Kreiss, B Richardson. Compliance with antiretroviral regimens to prevent perinatal HIV-1 transmission in Kenya. AIDS. 17(1): 2003; 65–71.

- Y Nebie, N Meda, V Leroy. Sexual and reproductive life of women informed of their HIV seropositivity: a prospective cohort study in Burkina Faso. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 28(4): 2001; 367–372.

- A van der Straten, R King, O Grinstead. Couple communication, sexual coercion and HIV risk reduction in Kigali, Rwanda. AIDS. 9(8): 1995; 935–944.

- H Brou, G Djohan, R Becquet. When do HIV-infected women disclose their serostatus to their male partner and why? A study in a PMTCT programme, Abidjan. PLoS Medicine. 4(12): 2007; e342.

- C Hankins. Male circumcision: implication for women as sexual partners and parents. Reproductive Health Matters. 15(29): 2007; 62–67.

- C Kamenga, RW Ryder, M Jingu. Evidence of marked sexual behavior change associated with low HIV-1 seroconversion in 149 married couples with discordant HIV-1 serostatus: experience at an HIV counselling center in Zaire. AIDS. 5(1): 1991; 61–67.

- S Allen, E Karita, E Chomba. Promotion of couples’ voluntary counselling and testing through inflential networks in two African capital cities. BMC Public Health. 7(349): 2007 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-349.

- Voluntary HIV-1 Counselling and Testing Study Group. Efficacy of voluntary HIV-1 counselling and testing in individuals and couples in Kenya, Tanzania, and Trinidad: a randomised trial. Lancet. 356(9224): 2000; 103–112.

- O Grinstead, S Gregorich, K Choi, T Coates, and Voluntary HIV-1 Counselling and Testing Study Group. Positive and negative life events after counselling and testing. AIDS. 15: 2001; 1045–1052.

- S Maman, J Mbwambo, M Hogan. HIV and partner violence: implications for HIV voluntary counseling and testing programs in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. 2001. At: <www.populationcouncil.org. >.

- Desgrées-du-Loû A, Brou H, for the DITRAME PLUS Study Group. Conjugal risks after prenatal HIV testing: experiences from a PMTCT program in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, 2001–2005. Presented at: AIDS Impact, Marseille, 1–4 July 2007.

- SL McKenna, GK Muyinda, DL Roth. Rapid HIV testing and counselling for voluntary testing centers in Africa. AIDS. 11(Suppl 1): 1997; S103–S110.

- K Semrau, L Kuhn, C Vwalika. Women in couples antenatal HIV counseling and testing are not more likely to report adverse social events. AIDS. 19(6): 2005; 603–609.

- C Farquhar, J Kiarie, B Richardson. Antenatal couple counseling increases uptake of interventions to prevent HIV-1 transmission. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 37(5): 2004; 1620–1626.

- UNAIDS. The impact of voluntary counselling and testing. A global review of the benefits and challenges. 2001; UNAIDS: Geneva.

- TM Painter. Voluntary counseling and testing for couples: a high-leverage intervention for HIV/AIDS prevention in sub-Saharan Africa. Social Science and Medicine. 53(11): 2001; 1397–1411.

- P Gaillard, R Melis, F Mwanyumba. Vulnerability of women in an African setting: lessons for mother-to-child HIV transmission prevention programmes. AIDS. 16(6): 2002; 937–939.

- DK Ekouevi, V Leroy, I Viho. Acceptability and uptake of a package to prevent mother-to-child transmission using rapid HIV testing in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. AIDS. 18(4): 2004; 697–700.

- Orne-Gliemann J, Tchendjou P, Miric M, et al. Evaluating the feasibility and impact of couple-oriented prenatal HIV counselling and testing in low and medium HIV prevalence countries. Abstract TUPE0387. XVII International AIDS Conference. Mexico City, 3–8 August 2008.

- UNAIDS/WHO. AIDS epidemic update: special report on HIV/AIDS. Dember 2006. 2006; UNAIDS: Geneva.

- M Temmerman, J Ndinya-Achola. The right not to know HIV test results. Lancet. 345: 1995; 969–970.

- A Medley, C García-Moreno, S McGill. Rates, barriers and outcomes of HIV serostatus disclosure among women in developing countries: implications for prevention of mother-to-child transmission programmes. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 82(4): 2004; 299–307.

- A Desgrées du Loû. The couple and HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. Telling the partner, sexual activity and childbearing. Population-E. 60(3): 2005; 179–188.

- A Philpott, W Knerr, V Boydell. Pleasure and prevention: when good sex is safer sex. Reproductive Health Matters. 14(28): 2006; 23–31.

- J McGrath, D Celentano, S Chard. A group-based intervention to increase condom use among HIV serodiscordant couples in India, Thailand and Uganda. AIDS Care. 19(3): 2007; 418–424.

- S Allen. Effect of serotesting with counselling on condom use and seroconversion among HIV discordant couples in Africa. BMJ. 304: 1992; 1605–1609.