Abstract

Various support and self-help groups for people living with HIV and their families have developed in Viet Nam in recent years. This paper reports on a case study of Sunflowers, the first support group for HIV positive mothers in Hanoi, begun in 2004, and a sister group begun in 2005 in Thai Nguyen province. From April 2004 to early 2007, we carried out semi-structured interviews with 275 health care workers and 153 HIV-positive women and members of their families, as well as participant observation of group meetings and activities. Sunflowers have successfully organised themselves to access vital social, medical and economic support and services for themselves, their children and partners. They gained self-confidence, and learned to communicate with their peers and voice their needs to service providers. Based on personal development plans, they have accessed other state services, such as loans, job counselling and legal advice. They have also gained access to school and treatment for their children, who had previously been excluded. Although the women were vulnerable to HIV as wives and mothers, motherhood also provided them with social status and an identity they used to help build organisations and develop strategies to access the essential services that they and their families need.

Résumé

Ces dernières années, plusieurs groupes de soutien et d’auto-assistance pour les personnes vivant avec le VIH et leurs familles se sont développés au Viet Nam. Une étude de cas a porté sur Sunflowers, premier groupe de soutien des mères séropositives créé à Hanoi en 2004, et un groupe apparenté lancé en 2005 dans la province de Thai Nguyen. D’avril 2004 à début 2007, nous avons mené des entretiens semi-structurés avec 275 agents de santé et 153 femmes séropositives membres de Sunflowers et leurs familles, et observé les participants aux réunions et aux activités des groupes. Les membres de Sunflowers sont parvenues à s’organiser pour bénéficier des services sociaux, médicaux et d’aide économique vitaux pour elles-mêmes, leurs enfants et leurs partenaires. Elles ont acquis de l’assurance et appris à communiquer avec leurs pairs et à faire connaître leurs besoins aux prestataires de services. Sur la base de plans de développement personnel, elles ont obtenu l’accès à d’autres services étatiques, comme les prêts, l’orientation professionnelle et les conseils juridiques. Elles ont aussi pu scolariser et faire soigner leurs enfants, auparavant exclus de ces prestations. Bien que les femmes soient vulnérables au VIH en tant qu’épouses et mères, la maternité leur confère un statut social et une identité dont elles se servent pour construire des organisations et définir des stratégies donnant accès aux services essentiels dont elles et leurs familles ont besoin.

Resumen

En los últimos años han surgido en Vietnam diversos grupos de apoyo y autoayuda para las personas que viven con VIH. Este artículo informa sobre un estudio de caso de Sunflowers, el primer grupo para madres VIH-positivas en Hanoi, fundado en el año 2004, y un grupo asociado iniciado en 2005, en la provincia de Thai Nguyen. Desde abril de 2004 hasta principios del 2007, realizamos entrevistas semiestructuradas con 275 trabajadores de salud y 153 mujeres VIH-positivas, quienes eran miembros de Sunflowers, y con los miembros de sus familias, así como observación participante de las reuniones y actividades del grupo. Las mujeres de Sunflowers han logrado organizarse para acceder al apoyo y los servicios vitales sociales, médicos y económicos para sí mismas, sus hijos y sus parejas. Adquirieron confianza en sí mismas y aprendieron a comunicarse con sus pares y expresar sus necesidades a los prestadores de servicios. Basándose en sus planes de desarrollo personal, han accedido a otros servicios estatales, como préstamos, orientación profesional y asesoría jurídica. También obtuvieron acceso a la escuela y tratamiento para sus hijos, que anteriormente habían sido excluidos. Aunque las mujeres eran vulnerables al VIH como esposas y madres, la maternidad también les dio posición social y una identidad que utilizaron para ayudar a crear organizaciones y formular estrategias para acceder a los servicios esenciales que ellas y sus familias necesitan.

Rapid economic growth, socio-cultural changes and the relative availability of heroin have contributed to increased drug use among young Vietnamese men.Citation1Citation2 Needle sharing among drug users is common, with rates ranging from 20–70%, facilitating the spread of HIV.Citation3Citation4 The epidemic is still concentrated predominantly in young male injecting drug users (IDUs) in urban areas, borders areas and seaports, with infection rates between 30–60%.Citation3,5,6 Young adults aged 20–29 account for 50.5% of all HIV infections.Citation7 Although figures on HIV-positive women are greatly under-reported, women form a minority of those with HIV,Citation8 primarily as sexual partners of male IDUs. Their numbers are increasing, but access to services such as prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) is improving only marginally.Citation9–12 As actual or suspected drug users and sex workers, they face social rejection and criminalisation because intravenous drug use and sex work are considered “social evils” in Viet Nam. Within their families, they bear most of the responsibility for housework and care.

Forming or joining a support group can offer opportunities to access and cope with treatment and share personal experiences.Citation13–15Footnote* For women who have a low status in their own households, the emotional and practical support provided by such groups can be very important. In Viet Nam, distinctions between the state, civil society, and political and non-political state-sponsored organisations such as the Women’s Union, are blurred. While opportunities to form independent groups, including support groups, are increasing, they are still limited. Recent policy directives reaffirm the central leadership role of the Communist Party’s local “Peoples’ Committees” in all HIV/AIDS activities, including organisations for people with HIV.Citation16Citation17 In spite of this restrictive institutional environment, various groups for people with HIV and their families have developed in Viet Nam over recent years. Since 1999, the Women’s Union, a mass organisation under the auspices of the Communist Party, has supported “sympathy clubs” for women living with an HIV-positive family member – often mothers caring for their adult sons with HIV. Many international and national organisations have supported the establishment of groups of peer educators who do community outreach as well, as a strategy to encourage involvement in to their programmes. The number of self-help and support groups of HIV positive and HIV-affected persons not directly under state authority also nearly doubled between 2006 and 2007, from 34 to 74.Citation18

In Viet Nam, the state provides most health services, although HIV and AIDS services are mainly financed with international funding.Citation19 The creation of the first support group for HIV positive mothers in Viet Nam responded to concerns about poor access to treatment, support for HIV positive mothers and the risk of an increasing number of AIDS orphans.

This case study explores how HIV positive mothers in Vietnam organised themselves to access vital social, medical and economic support and services for themselves and their children. It examines the leadership strategies they developed to negotiate between the needs of their families, other infected and affected women, and the state. The barriers that hinder HIV-positive women from becoming politically active and speaking to the media are also explored.

Respondents and methods

We followed the development of the first support group for HIV-positive mothers in Viet Nam over a period of three years. Initially, data were collected in November 2003 for a rapid HIV/AIDS needs assessment in Hanoi. The findings were presented to policymakers, health and social service providers, and HIV positive people at a meeting to develop a plan to address the problems identified. Among the problems were the low number of women who accessed services, a lack of follow-up of HIV-positive women and a lack of understanding of their needs. The group proposed to start a special support group for HIV positive mothers under the umbrella of Viet Nam’s Red Cross Society in Hanoi’s Dong Da district. Over the period studied, the Hanoi-based group, who called themselves Sunflowers, grew from four mothers to 305 mothers and their family members and expanded to three other provinces, Thai Nguyen, Quang Ninh and Cao Bang. This study focused on the pioneering group in Hanoi, begun in 2004, and the first Sunflower group launched in Thai Nguyen in 2005. The data collection started in April 2004 with the Hanoi group and in 2005 with the Thai Nguyen group and ended in June 2007.

A research team with four members with medical backgrounds and three with social science backgrounds collected the data for this study. The researchers were all Vietnamese, with the exception of one expatriate social scientist. Three members worked as advisors with support groups and could therefore closely follow their work. Bi-weekly participatory programmes in Hanoi and monthly programme observations in Thai Nguyen allowed them to monitor the well-being of the women and their partners, children and extended families. The team reviewed minutes of meetings and programme documents, including group progress reports, financial information and narrative reports.

In 2005, 275 semi-structured interviews were conducted with health care workers and other key stakeholders on the quality and quantity of prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) services in Hanoi and Thai Nguyen. Workers were selected from national and provincial hospitals providing PMTCT or antiretroviral therapy, which also provided voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) and HIV testing before deliveries. Researchers visited the VCT facilities and antenatal care departments, interviewed the department heads and at least one lower-level staffperson with at least one year’s relevant experience.

Having obtained informed consent, the research team interviewed a convenience sample of 56 HIV positive women in Hanoi and 28 in Thai Nguyen City. In addition, 34 HIV positive men in Hanoi and 13 in Thai Nguyen joined the interviews. Seven mothers-in-law in Hanoi and 10 in Thai Nguyen also participated in the study. In Hanoi, two fathers of HIV positive women, one sister, one sister-in-law and one brother-in-law were interviewed. All 153 persons responded to semi-structured questionnaires on HIV care and support, gender, family, self-help groups and access to antiretroviral medication. Most of the women were 20–30 years old and were raised in the city where their support group was located. All were literate. The women had been or were still married, and their husbands – alive or dead – had a history of injecting drug use, visiting sex workers or both. It is likely that the husbands infected their wives.

Respondents were not asked their surnames, addresses or any other identifying information in order to ensure privacy and confidentiality. All data sets, questionnaires and tapes were stored in a secure office. First names were changed to protect confidentiality. The study proposal was reviewed by the ethical review board of Hanoi Medical University.

Findings

Seeking acceptable HIV-positive identities

The State authorities wanted to help HIV positive mothers because they felt the women were more in need of assistance than male IDUs. They also believed programmes for mothers had a better chance of being implemented.

“Drug users really need our support, but if we allow a group of known users to meet in our building we might get in trouble with the police.” (Vice-director, Red Cross Society, Dong Da chapter, 2004)

A drug-free group, on the other hand, could be a socially acceptable environment for families who might not otherwise allow their female relatives to join. Initially, members had little confidence in themselves and in their roles as mothers, because of their HIV status. This was in part due to the association of HIV with “social evils” and judgments that people with HIV are not suitable as parents.Citation20 In the early days, Sunflowers’ outreach materials emphasised that members were HIV positive mothers who had no history of drug use and sex work, and that group members suspected of drug use had to undergo drug testing. Many members avoided saying openly that they lived with a drug user; instead they portrayed their husbands as normal Vietnamese men who went to play (di choi) with sex workers. Over time, some relaxed their guard slightly, admitting that their husbands might have tried drugs “a few times”.

These HIV positive mothers, living in a patrilinear and patrilocal society, felt isolated from their own families in the households of their in-laws. Thus, the group meetings provided emotional relief and increased the women’s confidence. Being able to connect to others who can share experiences can be particularly important in situations where people have a stigmatising disease or are considered socially deviant.

“I felt alone and weak. I used to keep my feelings to myself because I was afraid that I would not be accepted if I spoke about my problems. I am confident in myself now that I have been able to share with so many women like me and they have told me that they feel better listening to me.” (28-year-old HIV positive woman, Hanoi, 2005)

Broadening scopes

Over the three years that we followed their work, the support groups gradually increased their members’ understanding of the broader contexts that shape the lives of women and children in the HIV epidemic. Members’ attitudes towards male IDUs and sex workers became more sympathetic due to their greater understanding of the structural causes that limit an individual’s ability to make choices, for example. As mutual trust evolved among group members, the authorities were no longer requested to carry out drug tests, although it remains an important part of the Sunflowers’ culture that members abstain from using drugs. Attitudes towards domestic violence also changed – from being something that a strong woman should bear to something unacceptable. Two members now work in shelters for trafficked women and victims of domestic violence in Hanoi.

By 2006, the groups began to relax their eligibility criteria to include HIV positive widowers with children, and the caretakers of children of HIV positive mothers. Although grandparents and single male parents have been eligible for membership for some time, male involvement remains limited, partly because of female members’ experiences of living with husbands who are IDUs, as the following discussion on male participation in a group meeting in Thai Nguyen in 2007 illustrates:

Group Leader A: “We have to help children infected with and affected by HIV. We could invite widowers to join our meetings and learn to take better care of their children. Maybe we’ll need someone to take care of our children someday.”

Group Leader B: “Well, I don’t think they are very useful to us. These men all use drugs. That’s why their wives died of AIDS.”

Member: “Well, men could be useful for doing some heavy jobs. Our office roof needs fixing.”

The group laughed and agreed that HIV positive fathers could attend the group for advice on fatherhood and help to access health services. This decision reaffirmed the members’ central identities as mothers, as well as their new roles as managers, and not simply as beneficiaries of care and support services.

Emerging leadership

The Sunflowers support group was constituted as an offshoot of the Red Cross, and had its offices in a Red Cross building. This reflected legal necessity: in Viet Nam nearly all independent groups must be sponsored by a state-approved mass organisation. But it also reflected a desire to be protected by and from the state, and to be able to rely on the state to represent their interests when this is to their advantage.

The Sunflowers groups and the Red Cross negotiated the selection of group leaders, which was a learning process for both. Initially, few women were interested in positions of responsibility; hardly any considered themselves to be potential leaders. One of the first leaders used her position for personal gain, which prompted both group members and the Red Cross to take leadership elections more seriously, and to establish decision-making mechanisms for the group. However, formalising elections discouraged the women who lacked confidence and education.

“I do not want to represent the group because I cannot write very well. My parents were poor, so I am not very educated, and I feel very insecure about my writing and way of speaking.” (Thanh, one of the first members)

This lack of confidence was not permanent, however. While some women were slow to take advantage of opportunities available to them, Thanh was among the first women to take out a loan when the group made a microfinance arrangement with the Women’s Union.Citation21 Untypically, Thanh took literacy classes, and later a proposal-writing workshop at a national university. At the time that she joined the group her daughter was excluded from school because of her parents’ HIV status. But Thanh gained enough confidence to discuss the issue of discrimination with the school headmaster, who reinstated her daughter, and she is now a group leader.

Increasing access to antiretrovirals and other support, care and services

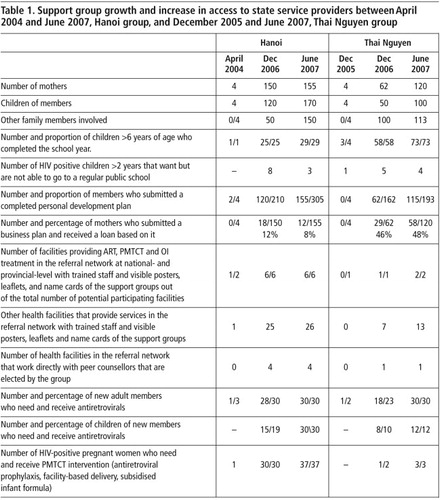

In April 2004, the new Hanoi group had four members, and there was only one facility providing services for antiretroviral treatment, PMTCT and opportunistic infections. As Table 1 below illustrates, by December 2006 Hanoi members had progressed from a situation of poor adult access to antiretrovirals and no access to medicine for children, to one where all children and their parents could obtain free drugs, with further increases by June 2007. This is a far cry from the first year, when the husbands and children of several members died because they were unable to access treatment. (Roughly one-third of Sunflowers’ children born in 2004 were HIV positive, and several died.) The table also shows the expansion of the referral network, i.e. the number of formally arranged referrals to specific services and the network of services as a group that participate in this network. The services in the network had risen from two to 32 service sites in Hanoi and eight to 15 service sites in Thai Nguyen, reflecting both the increasing number of services available and the ability of the groups to enter into strategic alliances to access them.

Linking personal needs with state services

Through participation in the groups, members became more self-confident, which helped them improve their ability to communicate with their peers as well as voice their needs to service providers. In both provinces about half of the members completed a personal development plan to prioritise their medical, economic and social needs. Based on their plans they received tailored support to access other state services, such as loans, job counselling and legal advice on issues such as the registration of land rights. Nearly all group members in both provinces were able to gain access to school for their children, who had previously been excluded, reflecting increased negotiation skills with the authorities.

In 2004, it was not uncommon for HIV positive women to be denied access to health care. Yet by 2006, both groups’ initial members had transitioned from recipients of aid to advocates for their peers, working with health staff to refer women to hospital-and community-based services, as well as to groups providing services to male partners and IDUs.

National-level health staff initially worried about the capacity of people with HIV to understand treatment regimes, but this changed over time. Doctors reported that patients who were able to talk to peer counsellors in the hospital and join community-based groups adhered better to treatment.

“I was a bit worried about the peer educators because their educational level is low. But I can now see that they are very useful to us. Patients tell them things that they do not want to tell us, and actually, frankly speaking, we have no time to listen.” (Medical doctor, national-level hospital, Hanoi, 2007)

Public, media and political involvement

Several members who work in partnership with national hospitals have presented their work to national authorities and policymakers. At one hospital, peer counsellors have a formalised role, with terms of reference. This suggests a certain political empowerment and recognition for members of Sunflowers, and may contribute to institutional reforms. HIV-positive women working with service providers to evaluate and improve the quantity and quality of service delivery affects power relations, and as such can be considered political acts. Yet these achievements are made within the limits of the traditional, private roles of mother and caretaker. Some of their accomplishments to improve public services remain invisible because the women avoid the public political sphere.

From the outset, group members struggled to balance their desire to raise public awareness and mobilise new members with their own fears of being rejected by, and losing protection from, state authorities. Soon after the first group was launched, four members and several Red Cross staff appeared at a World Bank Innovation Day event dressed in ao dai, the traditional Vietnamese formal dress, to counter negative stereotypical images of people with HIV. However, when the HIV-positive women, who had designed a public campaign against stigma and discrimination, won an award for their efforts, they delegated Red Cross staff to accept the honour, as they were too fearful to come forward.

Several members of Sunflowers have helped in the production of media projects, including a radio documentary on isolation and a fictional film on the unequal treatment of men and women with HIV. Members have taken part in installation art performances on the rights of HIV-positive mothers to raise their own children, which were broadcast on national and international television. The fixed component of the installation art piece is on display at the National Museum for Women in Hanoi. Yet during the performance associated with the installation, group members wore heavy makeup and wigs, and the museum exhibit includes no close-up pictures that might identify them. Only one HIV-positive mother has chosen to “go public” as of this writing; she will be the first in the group to openly appear in a documentary film at the end of 2008.

Discussion

Support groups aimed at helping HIV-positive women organise themselves and pursue practical and strategic, gender-based needs are shaped in part by interpersonal and internal processes within the group. The importance for members to share a common identity as well as interests and needs has been documented in studies examining the conditions for community empowerment.Citation22Citation23 The founding Sunflowers group reshaped a negative HIV-positive identity. Instead of being associated with social deviance, members stressed a more positive identity as HIV-positive mothers. This attracted new members and was acceptable to both their families and the authorities. Although the mother-focused approach of the Sunflowers at the time of the group’s inception was unique, the process of finding acceptable identities to interact with the state reflects the experiences of self-help groups for people with HIV more generally in Viet Nam.Citation18 However, developing a public political persona continues to be hindered by both institutional and policy barriers, as well as the women’s own ambivalence about becoming leaders and their fear of losing their anonymity.

In Viet Nam, getting pregnant and becoming mothers puts women at particular risk of contracting HIV. Yet motherhood also grants women a certain social status, while being childless is stigmatised. As HIV-positive mothers, Sunflowers’ members reported feeling like unfit parents, a reflection of negative broader social opinions on HIV and its association with “social evils”. This negative identity, as well as the assumption that HIV-positive women are beneficiaries rather than partners in state social service and health services, was transformed through participation in the group.

Several studies have found a strong connection between the ability of community groups to mobilise resources and their ability to bring about social and political change.Citation24 Sunflowers managed to mobilise access to life-saving medicines and other critical services. Access to resources on its own does not necessarily lead to critical thinking and problem-solving, however, nor have social and political impact. And communities sometimes fail to adequately utilise resources they receive – with water and sanitation projects, for example. A number of authors have emphasised the importance of the development of reflexive skills in social and political change.Citation24–27 Our findings suggest that critical thinking skills and increased access to resources may be interlinked. Having access to services, medicines in particular, gave women greater confidence in themselves and their relationship with the authorities. Once their immediate needs were taken care of, members used the space to reflect about other issues.

Maxine Molyneux proposed a distinction between practical and strategic gender interests to distinguish between women’s needs arising from immediate necessity, based on the sexual division of labour, and their longer-term interests in transforming social relations and enhancing their status. This distinction suggests there is a hierarchical relationship between grassroots women’s organisations that deal with practical issues, and those oriented towards policy reforms. It has been argued that such a division contributes to development planning that is either strategic but impractical, or practical but not strategic.Citation28 Yet studies of grassroots organisations in settings such as Peru and Brazil have demonstrated that women’s practical issues are directly related to national, strategic socio-economic issues.Citation29Citation30

Our findings suggest that practical and strategic needs are better conceived of as a continuum rather than hierarchical and separate. While antiretroviral treatment is an immediate practical need for PMTCT and everyone with AIDS, as HIV-positive mothers, members of Sunflowers have both urgent and long-term needs. The strategic alliances between the group and service providers were actively negotiated and created with the help of the state, partly because initial capacity for leadership and strategic networking by the group was limited, and partly because of national policy. The state took the lead in the establishment of a referral system between the groups in both Hanoi and Thai Nguyen and various services, while both groups elected their own internal leaders.

Our findings indicate that such joint leadership is possible within existing power and gender structures in Viet Nam, where the state has traditionally emphasised the importance of motherhood and women’s role as caretakers. The embrace of maternalism by members of Sunflowers – as a means of accessing previously restricted state services – has a certain strategic value: it permits new groups to access services, albeit within traditional gender roles. A maternalistic strategy is not new, and has been criticised for celebrating self-sacrifice as an essential feminine attribute, and therefore reinforcing traditional gender roles.Citation31Citation32 States as diverse as Brazil, Peru, Indonesia and Spain have responded differently to women’s grassroots networks at various times, but have also used such networks to rely on the provision of services without pay.Citation29–33 In the long run, whether or not the Sunflowers will be able to affect the kinds of policy changes that could really ameliorate their HIV-related care and support tasks, in addition to their other (unrecognised) household work, depends on their willingness to appear in public and challenge some of the assumptions about Vietnamese motherhood.

Notes

* Support groups generally form to recruit and mobilise peers in an informal, non-hierarchical way to share experiences and provide social support.

References

- Minh Tran Thu, Hien Nguyen Tran, H Yatsuya. HIV prevalence and factors associated with HIV infection among male injection drug users under 30: a cross-sectional study in Long An, Vietnam. BMC Public Health. 6(248): 2006; 1471–2458.

- J Werner, D Belanger. Gender, Household, State: Doi Moi in Viet Nam. 2002; Cornell University Southeast Asia Program Publications: New York.

- Ministry of Health. Decision149/BC-BYT. Five-year review workshop on HIV/AIDS prevention and control in 2001–2005 and action plan for 2006–2010. 2006; Hanoi Medical Publishing House: Hanoi.

- UNAIDS/World Health Organization. Epidemiological fact sheets on HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted infections. 2004. At: <http://data.unaids.org/Publications/Fact-Sheets01/vietnam_EN.pdf. >.

- CSIS. HIV/AIDS in Vietnam. 2006; CSIS: Hanoi.

- VAAC. Report on HIV sentinel surveillance survey in 2005. 2005; Vietnam Ministry of Health: Hanoi.

- Nguyen Tran Hien. Situation of HIV/AIDS/STI Surveillance in Vietnam. National conference on HIV/AIDS Monitoring & Evaluation, Da Nang, 2007.

- Anh Nguyen Thu, P Oosterhoff, A Hardon. A hidden epidemic among women in Vietnam. BMC Public Health. 8: 2008; 37.

- UNAIDS. Report on the global AIDS epidemic 2006. 2006; UNAIDS: Geneva.

- GSO, NIHE, ORC Macro. Vietnam population and AIDS indicator survey in 2005. 2006 [cited July 27th 2007]. Available from: <http://synergyaids.com/documents/VietNamPop&AIDSIndictorSurvey.pdf. >.

- World Health Organization. Progress on Global Access to HIV Antiretroviral Therapy, a report on 3 X 5 and beyond, 2006. March. 2006; WHO: Geneva.

- Ministry of Health. HIV/AIDS Estimates and projections 2005–2010. 2004. At: <http://unaids.org.vn/resource/topic/epidemiology/e%20&%20p_english_final.pdf. >.

- B Gidron, MA Chesler. Universal and Particular Attributes of Self Help: A Framework for International & Intranational Analysis. Prevention in Human Services. 11(1): 1994; 1–44.

- D Klass. The dynamics of self-help in healing parental grief: the role of the compassionate friends. Katz Hedrick Isenberg. Self-Help, Concepts and Applications. 1992; Charles Press: Philadelphia, 231–249.

- T Powell. Self-help Organizations and Professional Practice. 1987; NASW: Silver Spring.

- Communist Party of Vietnam. Kinh ethnic. 8 December 2007. At: <www.cpv.org.vn/details.asp?id=BT15100430381>.

- Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Decree No.108/2007/ND-CP detailing the implementation of a number of articles of the law on HIV/AIDS prevention and control, 2007.

- Health Policy Initiative. Mapping of PLHIV groups Viet Nam, August 2006–2007. Hanoi, 2007. (Unpublished)

- Ministry of Health. HIV/AIDS, Country Profiles. 2007; Vietnam Administraton of HIV/AIDS Control: Hanoi.

- P Oosterhoff, Anh Nguyen Thu, Yen Pham Ngoc. Dealing with a positive result: risks and responses in routine HIV testing among pregnant women in Vietnam. AIDS Care. 20(6): 2008; 654–659.

- P Oosterhoff, Anh Nguyen Thu, Yen Pham Ngoc. Can micro-credit empower HIV+ women? An exploratory case study in Northern Vietnam. Women’s Health and Urban Life. 7(1): 2008

- G Laverack. An identification and interpretation of the organizational aspects of community empowerment. Community Development Journal. 36(2): 2001; 134–145.

- M Wegelin-Schuringa. Participatory approaches to urban water supply and sanitation. 1992; IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre: The Hague.

- A Eisen. Survey of neighbourhood-based comprehensive community empowerment initiatives. Health Education Quarterly. 21(2): 1994; 235–252.

- S Evans. Personal Politics: The Roots of Women’s Liberation in the Civil Rights Movement and the New Left. 1980; Alfred Knopf: New York.

- A Sen. Gender and cooperative conflict. I Tinker. Persistent Inequalities. 1990; Oxford University Press: Oxford.

- P Freire. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. 2000; Seabury Press: New York.

- S Wietringa. Women’s interests and empowerment: gender planning reconsidered. Development and Change. 25(4): 1994; 829–848.

- Y Corcoran-Nantes. ‘Female conciousness’ or ‘feminist conciousness’? women’s consciousness raising in community based struggles in Brazil. BG Smith. Global Feminisms since 1945. 2000; Routledge: London, 81–99.

- Boesten J. Negotiating womenhood, reproducing inequality, women and social policy in Peru. PhD thesis. University of Amsterdam, 2004.

- S Pedersen. Catholicism, feminism, and the politics of the family during the Late Third Republic. S Koven, S Michel. Mothers of a New World: Maternalist Politics and the Origins of Welfare States. 1993; Routledge: New York, 246–276.

- M Nash. Defying Male Civilization: Women in the Spanish Civil War. 1995; Arden Press: Denver.

- ID Utomo, SA Arsyad, EN Hasmi. Village family planning volunteers in Indonesia: their role in the family planning programme. Reproductive Health Matters. 13(27): 2005; 73–82.