I am a sexuality activist, researcher and theorist, with 35 years of experience working, thinking, writing and debating in sexuality and gender politics, and 25 years of working in HIV/AIDS. I can talk about sex under water! For me, like everyone else the first time – losing my cherry – was an important moment marking a new phase of my life and I have talked with amusement about that moment with friends and in my work. I want to tell another tale here, no less important in marking a new phase in my life, but perhaps with quite different prospects. I want to tell a tale about losing my chestnut.

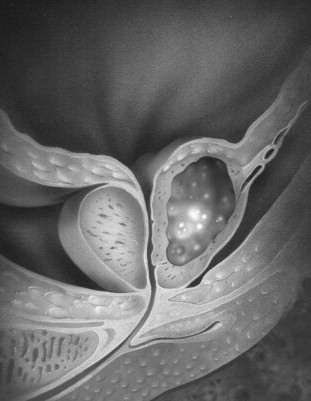

Cancer. That was the word I dreaded, but had been anticipating as a diagnosis for nearly a decade. Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men after lung cancer and, it seems, growing in prevalence to equal breast cancer in many resource-rich and developed countries. Indeed, there are just on 12,000 new diagnoses in Australia each year (almost a quarter of a million in the US). It comes at you in scales, scores and stages, with actuarial tables on ages, survival rates over time – it is definitely “men’s business” and is handled in a matter-of-fact, man-to-man way. Diagrams of your “chestnut” (it looks a bit like one in the drawings) with little wings (seminal vesicles) make it look like a logo for international airmail, but it is held to earth by a kite string-like urethra. You can live without it, but how well you live is the next question after how long. There is not much room for emotion in the urologist’s office.

I received the news, the detail, the recommended action – in my case, a radical prostatectomy (RP), complete removal of my chestnut – and a sketch of the prospects for a future life. Then, with a manly shake of hands and a subsequent, decision-yielding appointment made with the secretary who has seen all this before, I found myself on the street heading somewhere, home, work, a bar, with a cloud dulling my senses and numbing my heart. At least for a while.

A decade before, I had had an infection in the prostate. How did I know? Some blood in my semen. How did I see that? As a gay man with a reasonably active sex life, I knew about safe sex. “Cum on me, not in me” was a key slogan used in gay men’s HIV prevention for years. Need I say more? My general practitioner (GP, i.e. internist, family physician) ordered a Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) test, the major diagnostic tool for assessing prostatic problems, and did the usual Direct Rectal Examination (DRE). The DRE revealed a somewhat enlarged prostate, but for my age (heading toward my late 40s then) this was not entirely unusual as most men’s prostates start enlarging with age. But the surface of the prostate he felt was smooth – no bumps – a good sign as bumps indicate a possibly cancerous growth starting to press against the outside capsule that contains the prostate. The PSA test result came back a “six”, considered a bit high for my age and possibly indicating some problem, but not necessarily cancer. Elevated PSA scores occur with a range of prostatic conditions, including the enlarging that comes with ageing.

Off to the urologist – the men (mainly) who “own” prostates. A further PSA test, another DRE, a urine flow test (enlarging prostates can increasingly inhibit urine flow and control) led to a decision to undertake a biopsy. This so-called simple day procedure under a general anaesthetic left me peeing blood for a month. The blood should not have taken that long to clear. As with every new procedure and the associated tests, I looked for the good news. There was no sign of cancer. An infection of the prostate was diagnosed and a quite long course of antibiotics prescribed. Duly healed. But I kept watch, asking for a PSA test and DRE annually from my GP, and neither showed any changes for nearly eight years. There were a few more moments with blood in semen, but my GP (at a gay men’s health practice) concluded that these were not of concern because of the steady PSA scores, which remained at six for all that time.

Then, at the end of 2006, as part of my annual check-up (my cholesterol and blood pressure were a little above average and I was more concerned about those), the PSA test returned a score of eight. It is such jumps in scores that are more worrying than slow elevation, and it was off to the urologist again – a new one, younger, in a specialist urology clinic attached to one of the better private hospitals in Melbourne, Australia, where I live. Another DRE (no bumps) and a PSA test (it had dropped to seven) were good signs, it seemed. It could have been another infection that fed the PSA blip, given the steady sixes over the years, but with the elapsed time since the last biopsy, the urologist advised that I have another one as a PSA score of seven was high for my age, by now 55. I put it off, too much overseas travel for work –HIV/AIDS is such a pressing field to work in, always urgent, never-ending – and I finally underwent the procedure in April 2007, fully expecting (hoping for) anything other than cancer.

Cancer. The word I dreaded.

The options were canvassed, and an RP was recommended because of my scores and age – young for this, although diagnoses are increasingly made at younger ages as PSA testing becomes regularly used as a screening test, and more men become aware of prostate problems through public health education and are seeking advice earlier. The prognosis for full recovery and survival after an RP is getting better: roughly an 85% chance of remaining cancer-free at ten years, although this simple figure hides a multitude of ifs-and-buts that one finds out about later. I sought a second opinion, organised by a colleague (working in Australia’s largest sexual health and sexuality research outfit has many benefits, but this was an unexpected one). Same diagnosis, same recommendation, same prognosis; no choice really if I wanted to live at least longer than if I did nothing.

Now, being a kind of nerdy, intellectual type with all the resources that a university academic has at his disposal, I hit the internet and the databases for everything I could find. Well, there is lot of medical science out there, many big outfits at work (e.g. Johns Hopkins; the Prostate Cancer Foundation in Australia; experimental surgical procedures; many more options and research) and there are considerable differences of opinion on the increasing use of RPs and at younger ages, and quite a deal of health education advice, chatty little booklets, websites. I learned I faced a range of odds, depending on how big the cancer was, its stage (there are four of them with various subtypes and descriptors) indicating whether it was contained or had metastasised (the biopsy cannot reveal everything), and what the eventual Gleason score was (a ten-point scale: one to five is considered low-level cancer, six to seven is considered intermediate level, eight to ten is considered aggressive; the score is made up of two parts depending on the type of cancer cells present). My Gleason score of seven eventually comprised 80% three and 20% four in the post-RP pathology tests, but the seven itself on biopsy was a concern. Then, there were a range of probable side-effects to consider.

An RP is no simple fix. The surgery could leave me with a urinary continence problem that might dog me for the rest of my life and with unpredictable sexual dysfunction. The second opinion also revealed that I would never ejaculate again no matter what else did or did not occur, and that was a real blow, for it signalled symbolically more than anything else that sexual pleasure would never be the same again. It was also a fact notably absent from much of the public health literature, which is surprisingly coy when it comes to the sexual side-effects of RPs. The reproductive health side-effects for men young enough and with an interest in having children are also rarely mentioned, as prostate cancer is assumed largely to be an older man’s disease. Sexual and reproductive health in this game is equated mostly with erectile function.

It is all a bit heterosexist too. All the brochures I was given by helpful nurse counsellors never mentioned gay men with prostate cancer. One from the Queensland Cancer Council buried toward the back a small photo of two men, but the word “gay” was not mentioned anywhere. When questioned by a colleague about this, the reply was that the Council never mention the sex of the partner in the text, so it is gender non-specific. Any gay man can tell you how specific that actually is by the way sexual relations and activities are rendered in the text itself; just using “partner” does not render any text non-heterosexist. No mention is made of gay men who might also be HIV-positive, or where a gay male couple might both have the disease. And, of course, there is no mention of gay sex. There was one reference at the back of the booklet, which, to my knowledge, was then the only English language book on gay men and prostate cancer in the world.Footnote* I ordered it immediately. It was quite useful if not very rigorous or helpful with the latest developments; its testimonials from men recovering from various treatments were cautionary and did not invite great optimism for a future life, fully recovered. But my growing recognition was that there is no full recovery from this even if the cancer was successfully removed.

I had a month to wait until a vacancy came up on my surgeon’s list. It was to happen at the private hospital where his clinic was based. My private health insurance (I have sustained the top level of cover for years since the first biopsy) would add to the funding available from Australia’s national health system, Medicare; but I would face not insignificant out-of pocket, co-payment costs, a result of the messy hybrid national health system we have in this country. During that month, I organised my work, letting my staff know and making contingency plans for research projects (temporary supervision of junior staff; work plans for next months; even a video greeting for an international workshop that I was to have led but now could not attend). My colleagues were wonderful in assisting me in all of this, pressed as they also were with heavy workloads, and I will ever be grateful to them for that support.

Family and friends rallied round wonderfully. My natal family all live in other states, but offered support and were always on the end of a phone if I needed them. My “sewing circle” of gay friends rostered themselves for support, transport, company, visits. Who says there is not gay family! Being single and unpartnered at this time in my life, this sharing of the burden of care and support in so many ways was both a surprise (was I actually deserving of this?) and hard to take for someone who has always been fiercely independent and self-reliant. I also sought the services of a counsellor before and for three months after the surgery, as I had realised that the (inevitable) mental health side-effects were not deemed something warranting post-operative medical care.

The surgery itself went according to plan. In fact, the whole thing was like a fully scripted play: four days in hospital, ten further days at home with a catheter to manage, its withdrawal, then continence management, recovery over time and back to work in two months or thereabouts. It all sounded fairly straightforward. Very fearful about the surgery and the outcome, I headed off to hospital at 6.30 am – yes, these “barber/surgeons” (as they were once called) are early risers. Undressing in my hospital room, and after a quick good-bye to a friend who accompanied me that far, I was taken down to theatre, then a quick word with the anaesthetist, a needle in the arm, and “bingo”, I woke up three or four hours later with no diseased chestnut.

What I did have was pain. I was flat on my back with a self-managed morphine drip in one arm (I had had hopes that this bit might be a bigger buzz than it was), a tube draining my abdomen, all heading left of the bed, the catheter heading right. My legs were encased in gorgeous white pressure stockings (“they will come in useful for long distance flying afterwards”, said the nurse – I was incredulous!). I was basically pinned there like that for two days, woken every hour for blood pressure and pulse tests, gratefully receiving backwashes from the night nurse, and definitely not at all hungry if very thirsty. I was sweating all the time and it was the middle of our winter outside. Finally, the pain relief was authorised by the surgeon (the anaesthetist had forgotten to note that) and things slowly progressed along their pre-ordained path.

This was nursing by numbers; the timing and procedures organised around shifts, daily processes (washing, food, morning tea, wonderful visitors, deliveries of flowers, a brisk early evening visit from the surgeon). A short visit from a physiotherapist had me regularly coughing deeply (and very painfully too) to ensure my lungs did not become congested. Day three saw me sitting in a chair for a while. Then, it was out with the drain – look the other way and think of England. The portable catheter bag was fitted, with instructions for its daily management delivered and duly practised. Walking up and down the corridor regularly was recommended and duly practised. Showering with the bloody catheter and its bloody bag was choreographed and duly practised; and before I knew it, it was time to go home. Surely not. I barely had even begun to recover, had had no sleep for days and was still in some pain. But this is modern medicine; it is all done by the book.

Going home was a blessed moment. No one had checked to see if I had anyone at home to support me…umm. I had, but they did not even ask. Two dear friends, a retired gay couple, actually came to nurse me for a month after the surgery – that was a remarkable gift – and were relieved occasionally by my gay family in shifts. Being at home became an obsession with process as well, managing the catheter (an endless chore), showering and dressing, eating, undressing, resting, walking, talking about process – all pursued with stoic determination to do as much as I could myself, even with my friends there caring for me. One’s world becomes so small, framed by the confines of one’s dwelling and focused on minutiae.

I read Nelson Mandela’s autobiography to remind myself that things were not as bad as I sometimes thought – he had had prostate surgery too. We had a daily reading from Pollyanna (so gay!) over morning tea – and did I ever play the “Glad Game” during that time! Eating became the central driver of a timetabled day – no wonder older people find themselves eating dinner at 5 pm. Sleeping was the worst part. I had to sleep on my back for ten days until the catheter was removed. I sweated bucketsful every night. No one told me to expect that. My bedding was soaked every few hours, and it was not from a leaking catheter. I lost almost 10% of my body weight within a fortnight of the surgery. My ribs were individually observable and palpable, and my butt – never callipygian at its best – disappeared. An angry red scar running from navel to pubis testified to what I had gone and was going through.

An unexpected call from the surgeon reporting that the pathology test on the prostate revealed that the cancer was contained within the capsule and there was no evidence of cancer cells in the seminal vesicles or other tissue was greeted with an instant flood of tears. I had not realised that my stoicism floated on a volatile emotional sea – something I was going to have to come to grips with as time wore on and a part of living through this experience that was never mentioned in the educational material, by the nurse counsellors, or ever spoken of – to this day – by the medics. This is a man’s disease and you take it like a man.

For those so minded, not only was my Gleason score a seven as explained earlier, but also my cancer stage could be described on the Tumour–Nodes–Metastasis (TNM) system as: “T1c” – the cancer cannot be felt during a rectal exam, but is discovered in biopsy after an elevated serum PSA level; “NO” – prostate cancer has not spread to lymph nodes; and “MO” – there is no evidence of distant spread or metastases from prostate cancer. These results, with the PSA score of seven before surgery, my age, and a skilled surgeon, had put me on the best footing I could be on to start this next stage of my life.

The day the catheter was removed marked another milestone: seconds before its removal, the nurse reverse-filled my bladder with saline, whipped out the catheter, and issuing a stern “hold it” had me walk a few paces to the toilet before releasing. I did all that and she calmly said, “Good, you won’t be incontinent”. Big news comes in laconic remarks. She handed me a complementary pack of Depend “guards [!] for men” and sent me on my way with blessed relief. This, however, soon gave way to the logistics of battling incontinence over the following weeks, with unreliable if improving bladder control, endless pelvic floor (Kegel) exercises, nerve-racking uncertainty during my first visits to a restaurant and to a concert, and learning to live without the extra control a prostate contributes to the bladder. I had to re-read my body; its sensations were unreliable (partly because of unavoidable nerve damage during surgery) and its messaging just was not working as I understood it – when I thought I was peeing I wasn’t; when I thought I was dry I suddenly wet myself. I was at times furious and quite desperate about it; at other times I just laughed like a child. Things improved fast, the odd accident notwithstanding, and Depend and I soon parted company, although to this day I travel with one in my briefcase. Not sure why really.

As for sexual dysfunction – what am I prepared to share with you, dear reader? Sexual dysfunction is almost entirely configured as erectile dysfunction in prostate cancer: can you get an erection, how firm is it, will it stay up, for how long? Sexuality as I understand it – comprising the whole shopping list from interest to arousal, to pleasure and pleasuring, to intimacy and orgasm, to discourse and meaning-making etc. – does not feature in the world of prostate cancer. My surgeon, a youngish bloke and pretty good at his job, promised we would start discussing sex at the six-week mark. When I reminded him of that, he instantly reached for the prescription pad and wrote a script for “Viagra”. Whoa, I thought; that was not what I was talking about. I had read in the brochures about erectile dysfunction and I knew that recovery of function was a very variable business. I had been posting and discussing this issue already in a “gay men and prostate cancer” Yahoo group, and there was a lively exchange going on about recovery of function and sexual pleasures, including new ones, and quite a deal of humour (and loss) in these postings. It was never going to be smooth sailing, that I knew; but I thought we would be talking about sexuality, not just about getting a “woody”. I know about “woodies”; they are personal and professional stock in trade. Living though cancer makes the professional personal.

Anyway, at this stage, I had already had the odd orgasm (some quite odd, given the nerve damage) and was coming to grips with that without ejaculation – I will forever miss that. My surgeon declared I was certainly “ahead of the pack” – the story of my life! Given that the average age of men experiencing prostate cancer is about 70, I should have hoped so. It is also a tribute to my surgeon’s skill that I had even this level of function at that stage, and it would be churlish not to acknowledge that. But a pre-surgery conversation about the always improving nerve-sparing techniques designed to save sexual function had not been encouraging. He suggested that for a young (for this disease), sexually active man like me, they take great care to do the least damage as is possible to the nerve bundles surrounding the prostate, but added: were I a 70-plus sexually non-active man… he drew a square with his index fingers in mid-air then chucked it over his shoulder. My heart sank for those 70-plus men who may no longer be sexually active with partners, but for whom the guilty pleasure of masturbation was a silent secret now lost forever to assumptions about age and pleasure. This was another moment when you realise how poorly men and our sexuality are thought about in medicine and health.

Back to my sex life… for I was/am determined to have one. All the pamphlets assume that the issue is about getting an erection for penetrative purposes, and that there is a willing little woman waiting there, legs apart, happy to let you practise for however long it takes to make it function. No discussion of pleasure, intimacy, loss, desire, reciprocity, relationality or, indeed, alternatives. I reminded my surgeon that I was a gay man, with fairly versatile sexual interests, and wondered also when it might be safe or wise to recommence anal intercourse (from both angles). Well, after a long technical digression on the distance between the prostate (or where it once was) and the anus – something I am actually very familiar with – I had received no answer. Journeys home from medical consultations are sometimes longer than the car ride. I went back to the Yahoo group for some good advice. Where I will get to on regaining sexual function is a tad unknowable, it seems, and somewhat unpredictable. As the nerves continue to heal slowly, it is really a case of practice, patience and persistence. But I have been assured again that I am “well ahead of the pack”.

There are other moments but not enough space here to tell them all. An ill-advised attendance at the Australian National Prostate Cancer Conference a few months after returning to work left me angry at the neglect of gay men, our partners and concerns entirely from the research agenda and the programmatic response. It was also too early for me to be hearing papers about hormone deprivation therapies coldly termed “castration”. The positioning of men as prostate cancer patients and consumers [sic] is light years behind HIV/AIDS, where people living with HIV/AIDS are worked with, not just on. The social science and public health prostate cancer research agenda is nowhere as well-developed as it is for breast cancer. The understanding of men’s sexuality that underpins the field is also at best rudimentary; it is as if 40 years of feminist and queer theory and activism have somehow passed urology by unnoticed.

To all intents and purposes my life is back to normal – well, that is how it appears to the surgeon, perhaps my colleagues and even myself in those hours where my mind is on what I am doing. Not so. There is before and after. There have been and still are moments of dark uncertainty and quiet despair. There is a private part of me now that no one reaches. Sometimes I doubt a future; other times I see only a truncated one – will the cancer come back, when? There is the mirror to remind me of a body forever changed inside and out. There is an endless “coming-out” process (right here, right now, again) as a cancer “survivor” – not that I have not been coming-out as a gay man all my life, but this time it is different. I now know something of what people living with HIV/AIDS experience in the act of disclosure. Pursuing a sexual life is complicated – one guy just gawked and said: “Oh, my God, what did they take out?” Just call me “Alien”! There is still anger and loss to deal with. Am I stronger for the experience, have I matured through the hardship, have I become a better person, do I deal with life one day at a time, and re-evaluate what really counts in life, counting my blessings as a result? Maybe, but fuck that! I just want my chestnut back!

Notes

* Perlman G, Drescher J, editors. A Gay Men’s Guide to Prostate Cancer. Binghamton NY: Haworth Medical Press, 2005.