Abstract

Nurse auxiliaries staff the majority of primary health service delivery outlets in low-income countries, particularly in rural areas with high unmet need for contraception. Yet often service delivery guidelines prohibit them from providing contraceptive methods such as the intrauterine device (IUD). Operations research in Guatemala and Honduras in 1997–2005, described in this paper, have shown that nurse auxiliaries can provide IUDs in a safe and clinically appropriate fashion, which can help improve women's choice of methods and decrease costs in health centres with physicians and professional nurses, and health posts. Empowering these health workers requires commitment at the health system and policy levels to a long-term strategy in which small pilot studies are first conducted, followed by phased scaling-up of the strategies, which can require several years. Training can be conducted both in high volume clinics or on-site in health posts. Simple measures such as mentioning the method during counselling and to users of different services and providing women and communities with printed materials have been effective in increasing requests for IUDs. These studies also showed that nurse auxiliaries can take on other reproductive health services, such as contraceptive injections.

Résumé

Les aides-soignantes constituent la majorité du personnel des points de prestation des soins de santé primaires dans les pays à faible revenu, particulièrement dans les zones rurales avec d'importants besoins insatisfaits en contraception. Pourtant, les directives sur la prestation des services leur interdisent souvent de délivrer des méthodes contraceptives comme le stérilet. D'après des recherches opérationnelles menées au Guatemala et en Honduras en 1997–2005, décrites dans cet article, les aides-soignantes sont capables de poser un stérilet en toute sécurité, ce qui peut élargir le choix de méthodes offertes aux femmes et diminuer les coûts dans les centres de santé dotés de médecins et d'infirmières, et dans les dispensaires. Habiliter cette catégorie de personnel exige un engagement aux niveaux politique et du système sanitaire en faveur d'une stratégie à long terme, avec d'abord de petites études pilotes, suivies d'un élargissement progressif des programmes, ce qui prend parfois plusieurs années. La formation peut être dispensée dans des centres à fort volume ou dans les dispensaires de terrain. Des mesures simples, par exemple citer la méthode pendant les consultations et devant les usagers des différents services ou distribuer des imprimés aux femmes et aux communautés, ont permis d'accroître la demande de stérilets. Ces études montrent également que les aides-soignantes peuvent assurer d'autres services de santé génésique, par exemple les injections contraceptives.

Resumen

Las auxiliares de enfermería suelen ser el único prestador de servicios en la mayoría de las unidades del primer nivel de atención en los países de bajos ingresos, especialmente en zonas rurales con altos niveles de demanda insatisfecha de anticoncepción. Sin embargo, las normas de prestación de servicios a menudo les prohíben proporcionar algunos métodos anticonceptivos como el dispositivo intrauterino (DIU). Investigaciones operativas realizadas en Guatemala y Honduras entre 1997 y 2005, aquí descritas, han mostrado que las auxiliares de enfermería pueden suministrar DIUs de manera segura y clínicamente apropiada, y así aumentar las opciones anticonceptivas de la mujer y disminuir los costos en centros de salud atendidos por médicos y enfermeras profesionales y en puestos de salud. Habilitar a estos prestadores de servicios exige un compromiso de largo plazo a nivel del sistema y de las políticas de salud, que implica la ejecución de pequeños estudios piloto y la ampliación de la estrategia en fases sucesivas, un proceso que puede durar varios años. La capacitación puede hacerse en clínicas con una alta casuística o en los puestos de salud. Medidas sencillas como mencionar el método durante la consejería y a usuarios de diferentes servicios, así como la distribución de materiales impresos a las mujeres y comunidades, han demostrado ser eficaces en aumentar la demanda del DIU. Estos estudios también han mostrado que las auxiliares pueden asumir la prestación de otros servicios de salud reproductiva, como los de anticonceptivos inyectables.

Up to 17% of all married women of reproductive age in 53 less developed countries surveyed do not want to have more children but are not using a contraceptive method.Citation1 Of those who are using a method, many lack access to long-acting and permanent contraception. This is particularly true in rural areas, where female and male sterilisation are scarcely available. The intrauterine device (IUD) is a method that could satisfy many couples' needs for long-term contraception, as an alternative to sterilisation, as well as for those who are undecided on future fertility but know they do not wish to have a further pregnancy in the next one or more years. Yet, the IUD is used by only 5% of married women or women in union in less developed countries, with the exception of China.Citation2

Despite the fact that several studies have shown that trained nurse auxiliaries and other paramedical staff can safely provide IUD services,Citation3–5 in many countries service delivery guidelines still restrict them from doing so. This is unfortunate because in most low-income countries, about 80% of the primary health care service delivery outlets are rural health posts staffed by a single paramedical health agent. In addition, these rural health posts are located where the largest unmet need for contraception is found. Training nurse auxiliaries in the delivery of IUD and other reproductive health services could also help to increase the availability of the method in health centres and hospitals. In Guatemala and Honduras, key informants reported that physicians and professional nurses often concentrate on providing curative services and delegate the delivery of preventive health care services such as contraception to nurse auxiliaries.

This paper reports on a series of operations research projects implemented in Guatemala and Honduras by their Ministries of Health, with financial and technical assistance from the Population Council.Footnote* The aim was to make the IUD and other reproductive health services, including contraceptive injections and Pap smears, more widely available, by training nurse auxiliaries and testing strategies to increase the demand for these services.

At the time these projects were conducted, 1997–98, 2000–2001 and 2005–2006 in Honduras and 2003–2004 in Guatemala, the Ministries of Health in both countries were providing primary health care through two types of facilities: health centres (located in towns with populations of over 5,000 inhabitants) with a minimum staff of one doctor, one professional nurse, one nurse auxiliary and one rural health technician, and health posts, with a minimum staff of one nurse auxiliary and sometimes one rural health technician, usually located in towns with populations of 1,500–5,000.

At the time of the studies in both countries, nurse auxiliaries were trained for two years in both private and public nursing schools and auxiliary nursing schools, following completion of the first three years of secondary school. The older nurse auxiliaries, who had graduated before the late 1980s, had achieved their degree with six years of elementary school and one year of health training. The main services provided by the nurse auxiliaries included vaccinations, child growth and development monitoring, and the prevention and treatment of respiratory and diarrhoea-related illnesses. They prescribed antibiotics for clearly defined cases and referred complicated cases to health centres that were better equipped to handle them.

According to their job description as regards reproductive health, nurse auxiliaries provided pre-natal and post-natal care and occasionally assisted women in childbirth. At the time the first project was conducted in Honduras, the only family planning methods provided by nurse auxiliaries were condoms and pills. Contraceptive injections were only just being introduced in both countries and were not available yet in health posts. Spermicides were not offered. Pap smears were available only in a few health centres and hospitals in large cities and provided by physicians and nurses only.

Feasibility study in Honduras

In 1997 and 1998, the Ministry of Health of Honduras, in collaboration with the local offices of the Population Council and AVSC, conducted a study to find out whether nurse auxiliaries could safely provide IUD services and vaginal cytology samples of high enough quality. Sixty nurse auxiliaries from the same number of health posts and 11 physicians and 23 professional nurses who supervised the auxiliaries from 21 health centres were trained. The criteria used to select participants were that they were working in a health centre or health post which was not offering either IUD or Pap smear services and was located in a town with a population of more than 3,000 inhabitants, had a permanent contract with the Ministry of Health, and lived in the community where they were working.

Training was conducted in two phases. The first phase consisted of training 19 trainers, who were physicians and professional nurses who offered family planning services in six health centres and outpatient clinics with a minimum of 25 IUD weekly insertions or removals and whose directors had agreed that their health centres could become training centres. The training workshop lasted five days and included an update on contraceptive methods, a review of the Official Service Delivery Guidelines for the Integrated Care for Women,Citation6 use of the evaluation instruments to certify the trained providers, and use of the data collection instruments that they and their students would have to fill out once the project was in progress. In total, the training cost US$142 per trainee, including transportation, lodging, per diem and materials.Footnote†

The training of the service providers consisted of one-week residencies for one or two trainees in each training centre. The mornings were devoted to clinical practice. In the afternoons trainees received theoretical training in family planning (such as advantages and disadvantages, indications, secondary effects, type of action, effectiveness and benefits of the different family planning methods, eligibility criteria, use of checklists to rule out pregnancy), Pap smears and use of data collection forms. The IUD insertion and removal practice sessions began with pelvic models and progressed to actual users who had requested the service.

Certification of the trainees for providing these services was carried out by observing whether they complied with service delivery guidelines listed in six checklists (one each for family planning counselling, IUD insertion, IUD removal, IUD check-up, combined oral contraceptives and Pap smears). Trainees were observed up to seven times, but once a given trainee showed competency in a given procedure, the observations with the appropriate checklist were not repeated. At the end of their training, trainees returned to their service delivery sites. Three months after completion of training, trainees returned to the training centres for refresher training, following the same training methodology. Although a training supervision system was designed with visits every two months, this was never put into practice due to logistical and financial limitations of the Ministry of Health.

The results of a simulated client study in 25 centres and posts and follow-up interviews with women who had received an IUD (122), pills (81) or condoms (19) showed that nearly all nurse auxiliaries offered and gave women information about the different methods available, helped them to choose a method, gave them instructions on how to use the method chosen and asked them to come back for a follow-up appointment. However, only about one half of the women were informed about side effects or were asked about potential contraindications, and few discussed sexually transmitted infections (STIs) or HIV during counselling. A follow-up study more than one year after the end of the project showed improvement in most of the variables but discussing and checking for STIs continued to be carried out by a minority of providers in both health centres and posts. These results led to strengthening of the contents on counselling and contraindications contained in the training modules during the scaling up of the strategy.

In all, the 60 trained nurse auxiliaries inserted 805 IUDs and took 2,659 Pap smears over a 12-month period, compared to 1,225 IUDs and 3,186 Pap smears provided by trained physicians and professional nurses in the 21 health centres. No perforations were observed with any nurse auxiliary, and only three pregnancies were subsequently detected. Nearly 8% of women seen at health posts and 2.8% of women seen at health centres had expelled their IUD within two months after insertion, but these rates are consistent with ranges reported elsewhere.Citation2 A cost study carried out in five health posts showed that the costs per woman user varied according to two primary factors: the time invested in offering the service and the number of women to whom the service was offered. The average cost per new IUD user was estimated at US $3.61 in health posts and US $4.52 in health centres, a difference mostly due to the cost of the service delivery personnel.Citation7Citation8

Based on these results, the Ministry of Health modified the Official Service Delivery Guidelines for the Integrated Care for Women in 1999 and explicitly authorised nurse auxiliaries to insert IUDs and take cervical cytology samples.Citation9

Scaling up the new services

Despite the positive results obtained during the operations research study and the consequent change in the official service delivery guidelines, the Ministry of Health decided to conduct a second operations research project during the year 2000 to learn more about the implications of extending IUD services and Pap smears to rural health posts in a non-research context. In addition, the Ministry sought to evaluate the introduction of contraceptive injections in health posts. In contrast to the previous study, this study also provided information on the performance of nurse auxiliaries in health centres.

Training was conducted by the Ministry of Health, with the assistance of EngenderHealth and the Population Council, in three phases. First, six doctors and 24 professional nurses from 30 health centres were trained as trainers. Then, 126 nurse auxiliaries in 126 rural health posts and 57 nurse auxiliaries, 56 professional nurses and 24 physicians in 56 health centres that had not participated in the previous study attended eight five-day workshops in groups of 25–30 on family planning counselling that covered sexuality, reproductive health, quality of care, contraceptive methods, counselling techniques, verbal and non-verbal communication. Finally, one or two trainees at a time attended the training centres for five days, where they reviewed indications, secondary effects, mode of action, effectiveness, and advantages and disadvantages of the different family planning methods. Finally, they provided family planning and Pap smear services under supervision.

Particular emphasis was placed on determining the proportion of service providers of each type that completed the training and what the cost of the training was. Whereas all providers were certified to provide Depo Provera injections and Pap smears, only 59% of the nurse auxiliaries in rural health posts who began group training achieved certification for providing IUD services, compared to 70% of those working in health centres. In the case of professional nurses and physicians, the proportions certified for IUD provision were 89% and 100%, respectively. The main reason for not achieving certification was the insufficient number of women requesting IUD services in some of the sites where training took place. According to accounting records, the cost of the training (including the cost of training trainers) was US $256 per trainee achieving certification to deliver IUD services.

A total of 127 nurse auxiliaries (88 in health posts and 33 in health centres) that achieved certification for providing IUD services reported service statistics for 1,061 provider-months in the year 2000. The reports showed that they attended a monthly average of 7.3 new family planning users (2.2 new pill users, 0.6 IUD insertions and removals, 3.7 new injectable users, 3.2 subsequent injectable users and 0.8 new condom users) and took 5.2 Pap smears. Nurse auxiliaries working in rural health posts provided fewer IUD insertions and removals (0.5), Depo Provera injections (3.5 to new users) and Pap smears per month (4.5) than auxiliaries working in health centres (1.0 IUDs, 4.2 Depo injections and 7.8 Pap smears respectively). Other analysis showed that only 58% of the certified nurse auxiliaries working in rural health posts inserted IUDs after the training, compared to 74% of certified nurse auxiliaries in health centres. With respect to the other services, more than 80% of the nurse auxiliaries reported having provided services to new users of other family planning methods, including contraceptive injections, and to have taken cervical cytology samples.Citation10

Qualitative interviews showed that the main reasons why certified nurse auxiliaries failed to provide IUD services were feeling that their training was insufficient and lack of confidence in their skills, lack of demand from women and lack of equipment. Those who did provide the services said they liked the activity because it required higher technical skills than most of their other tasks and because it was helpful for women in their community. They reported increased demand for services as a consequence of providing good counselling, promoting the method among service users and in the community, and receiving referrals to new users from satisfied users. To strengthen promotion of IUD services, the auxiliaries recommended training community health workers, providing educational materials, mentioning the method in counselling and to women seeking other services, and giving information to users to dispel myths. Other auxiliaries mentioned the need for more follow-up supervision to acquire greater confidence in their skills.Citation11

Based on these results, the Ministry of Health (with USAID funding and technical assistance from EngenderHealth) expanded the strategy to all rural health posts in the country over the following five years. Making the decision to extend training on the delivery of contraceptive injections and Pap smear services was not difficult because the results clearly showed that nearly all nurse auxiliaries could learn how to provide them and that a large majority actually used their newly acquired skills when they returned to their health centres or posts. In contrast, a smaller proportion of nurse auxiliaries completed the training to deliver IUD services and a smaller proportion of those who did so actually provided these services when they returned to their health units, which raised questions about the cost-effectiveness of the activity. In the end, this strategy was also scaled up, because the Ministry of Health considered that, although high, the estimated US $53 additional programme costs per insertion or removal for the first year after training (nearly US $15 per couple-year of protection), were reasonable when compared to the cost of providing other clinical methods in rural areas.

Test of a new service delivery model in Guatemala

In 2003, the staff of the Ministry of Health in Guatemala became interested in replicating the experiences in Honduras as a way to decrease the large unmet need for contraception, estimated in 2003 at 27.6% of married women of reproductive age. In contrast to Honduras, the service delivery guidelines did not bar nurse auxiliaries from providing IUD services, but the method was used by only 1.9% of married women of reproductive age in the country, and only 5.9% of these had obtained the method from the Ministry of Health.Citation12

A diagnostic study in 2002Citation13 had shown that about half of the 254 health centres in the country did not have the equipment or trained personnel needed to provide IUD services and that IUDs were not offered at all in the 857 rural health posts. Many of the trained physicians and professional nurses in health centres did not provide the method due to their heavy workload and because they perceived the delivery of the method to be too time consuming and burdensome. Moreover, less than 40% of the providers discussed the IUD with women during family planning counselling. The diagnostic study also noted that many providers had misconceptions about the method, such as that it had a high failure rate, that it caused discomfort during intercourse, that if pregnancy occurred it could cause side effects to the fetus, and that it could become embedded in the uterus. As for potential users, less than 54% of women had heard about the method; those who had heard of it knew only a few of its characteristics and believed the negative rumours they had heard about it. Few women knew that the Ministry of Health offered IUD services; they identified private service providers as the sole source.Citation13

To address the specific conditions in Guatemala and use the lessons learned in Honduras, the model we tested used different selection, training, certification and community information components from those of Honduras. The selection criteria for auxiliary nurses included having worked for at least a year at a participating facility, endorsement from the district physician and chief nurse, proven manual dexterity, interest in family planning, and willingness to receive IUD service training. The group training was shortened to two days, and because there were few health centres with a large enough volume of IUD users to allow for training over a reasonably short time, the practical training with supervised insertions and removals was given on-site at the trainees' health centre or post. Trainees needed to identify women interested in receiving the method and inform the trainer–supervisor when at least three candidates had been given an appointment for the service; the trainees then conducted the counselling and service delivery under the supervision of a project instructor. Up to three trainer–supervisor visits were scheduled for each facility.

Finally, trainees were provided with brochures, posters and leaflets to facilitate the creation of demand for the IUD in the communities, as well as a manual explaining how the materials should be used and examples of suggested community informational activities.Citation14 In contrast to Honduras, the training did not cover contraceptive injections (because nurse auxiliaries were already providing them) or Pap smears (this service was not offered at all in most service delivery units).

The project was conducted in two phases. In the first phase, implemented in 2003, the strategy was tested in 26 health centres and nine rural health posts. In the second phase, in 2004, the strategy was tested in 68 additional health centres. In the second phase, no health posts were included, at the request of the new managers appointed by the incoming presidential administration, who in spite of the evidence were reluctant to have nurse auxiliaries performing insertions without the direct supervision of a physician. Also, the new 2004–2008 Ministry of Health Basic Guidelines and Health PoliciesCitation15 did not include family planning provision as a health programme and the only reference to family planning found was “meeting family planning demand”, a phrase that many district health directors interpreted as a directive not to offer unsolicited family planning services.Footnote*

In the first phase, 24 of 28 (85.7%) nurse auxiliaries from health centres who began training achieved certification, compared to 8 of 9 (88.8%) nurse auxiliaries in rural health posts. In the second phase, only 45 of the 66 nurse auxiliaries that began group training also started practical training; and only 24 of those who started practical training actually achieved certification, for a completion rate of only 36.3%. Part of the problem seems to have been that several districts sent a large number of staff to attend group training without having a clear idea of the implicit commitment to conduct community information activities and identify potential IUD users, or without intending to have all providers participate in the practical training and achieve certification. Most trainer–supervisors conducted only one visit to health centres, instead of two or three as in the first phase. Moreover, in addition to the new policy environment, in some districts there was limited time left for practical training before the end of the project.

The project in Guatemala offered a wealth of data to evaluate the new on-site training strategy. The duration of individual practical training in the different areas ranged from one to eight months, with an average duration of 5.7 months in the first phase and 2.3 months in the second phase. The shorter duration of training in the second phase seems to have been the result of excluding the rural health posts from the trial as well as the greater use of the jornada (health fair) strategy, in which a set of services are heavily publicised and scheduled to be given in one single day or week at the health centre.

Nurse auxiliaries at health centres required a mean number of 7.5 supervised insertions and removals to achieve certification, compared to the 6.1 needed by nurse auxiliaries in rural health posts participating in the first phase. Considering the duration of the training and the number of services, each nurse auxiliary conducted a mean of 1.5 insertions and removals per month during training, but this ranged from 1.1–10.6 in different districts. An analysis of service statistics showed that the number of women receiving IUD services in participating health centres increased during training by nearly four times over previous levels, from 18.3 to 71.5 services per health centre, suggesting the effectiveness of community information strategies to increase awareness and demand. A cost study showed that taking everything into account (time used by trainees, materials used, travel and per diem, supervision and instructors) the cost of training one nurse auxiliary using the on-site training model was US $392, substantially higher than the cost observed in Honduras, but perhaps unavoidable when introducing the method in very low prevalence settings.

The numbers of new IUD users in participating health centres were monitored for a few months after training activities ended; they remained at a level about 11.3% higher than in the pre-training period. In contrast, the delivery of other contraceptive methods (pills, condoms and contraceptive injections) decreased by about 10% in terms of couple-years of protection provided. Although the net change was not significant, health centre users made use of the greater opportunity for choice and a better method mix was achieved in terms of their preferences.

To further explore the extent of the institutionalisation of the strategy, in July–August 2005 the Population Council staff that had coordinated activities visited the 69 health centres and posts that had participated in the project and found 49 nurse auxiliaries who had completed training 8–18 months before. Of these, about 80% were continuing to provide IUD services at the time of the visit. Among those who completed training in October 2003, the mean number of IUD services provided per month during January–June 2005 ranged from 1 to 3 per provider by department. Among those trained during June–October 2004, the average number of services provided ranged from 0.5 to 5.2 per provider by department. These providers contributed about 30–60% of IUD services in their health units. The majority reported satisfaction with providing the method and only one perforation and eight pregnancies were reported from the time they started providing the service.

Different data were collected in the two project phases. An analysis of the clinical records of women who received an IUD in the second phase showed that the criteria most often used by providers for ruling out pregnancy was current use of contraceptive injections (35%), followed by the presence of menstruation (31%) and exclusive breastfeeding in the first three post-partum months (26%). The clinical records also showed that during the first phase, 389 women requested an IUD from a service delivery agent trained by the project, but 88 women (22.6%) were refused the method. The most common reason for not providing the IUD was vaginal discharge (leucorrhoea) identified during pelvic examination (38%), pelvic inflammation (25%) and cervical stenosis (13%). No lacerations or infections were recorded in the one-month follow-up clinical records. Only one pregnancy following expulsion was detected. The only complication recorded was one uterine perforation that was appropriately handled by the trainer. These rates are consistent with complication and failure rates observed in studies with higher level providers.Citation14

Some complications observed during supervision visits with implications for training included the lack of autoclaves in several service delivery sites, which made necessary the use of chlorine bleach solutions for disinfection. However, health units often ran out of bleach, and providers needed to buy commercial chlorine solutions from local stores, which came at different concentrations than the one distributed by the Ministry of Health. Supervisors noted that service providers often were unable to prepare solutions with the appropriate concentrations for disinfection. Use of the clinical checklists and instruments was also not systematic and needed to be reinforced in each visit. Finally, although a large number of women did not receive an IUD because the providers suspected the presence of an STI, they had not been trained to resolve the problem. They needed to be instructed to provide such women with an alternative contraceptive method and be trained either to treat the STI or refer women to where treatment would be provided.

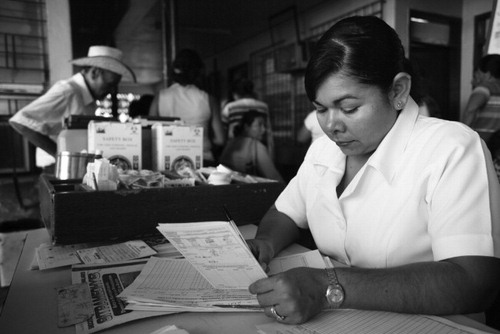

Regarding the characteristics of women who requested an IUD, the clinical records showed that about one-third of them had never used a contraceptive method before. Forty per cent of them did not want any more children, and 90% of those who wanted more children preferred to space their next birth by more than two years. In general, the data showed that the women were young, poor, with large families and low levels of schooling.

Outreach activities to increase demand for services

For training of nurse auxiliaries in the delivery of IUD services to be a cost-effective strategy, demand needed to be increased and sustained – not just in terms of the costs involved but also to maintain the skills of providers. In 2005 and 2006 the Ministry of Health in Honduras tested a community information strategy to assess the degree to which it helped to increase the demand for IUD services.

As part of the study, 41 health centres and posts were randomly assigned to two groups. In the intervention group, providers were trained to conduct information activities for women seeking contraception and the community. They were given a set of informational materials including: (1) a manual for communicating information about reproductive health services, (2) a flyer and a poster highlighting the key attributes of the IUD, and (3) a brochure explaining the characteristics, advantages and disadvantages of the IUD. The monthly average of IUDs provided by the health centre in that group doubled from 1.1 to 2.0, whereas in the control group it decreased from 1.7 to 0.8. This drop may have been a consequence of the emergency caused by two hurricanes that struck Honduras while the study was under way, rather than anything to do with the services, however.

The intensity with which the health centres implemented the communications strategy was correlated with a corresponding increase in the number of IUDs provided. These results suggest a potentially significant increase in access to IUDs on a larger scale; if the strategy were expanded to all 1,108 Ministry of Health health centres and posts in Honduras, the annual number of women choosing to use the IUD could increase from 11,500 to about 20,000 new users. Moreover, clinic records showed that the strategy attracted women who were most in need of family planning services (women in the intervention group were more likely never to have used contraceptives or used an ineffective method; they were also younger, poorer, with larger families and lower educational levels than women who chose the IUD in the control group). Finally, data from 18 pre- and 18 post-training simulated patient visits to health centres and posts in the intervention group showed that nurse auxiliaries had not biased their counselling to favour the IUD as a consequence of the training and that the counselling had improved.Citation16

Discussion

Programmes in both Honduras and Guatemala have shown that it is possible to train nurse auxiliaries to provide IUDs in a safe and clinically appropriate fashion and that doing so can help improve women's choice of methods and decrease costs at primary health centres and posts. Empowering these health workers requires commitment at the health system and policy levels to a long-term strategy in which small pilot studies are first conducted, followed by phased scaling-up of the strategies, a process that can require several years.

Where feasible, training can be conducted in service delivery sites with a high enough volume to allow nurse auxiliaries to be trained in a relatively short time. In low prevalence settings, on-site training can be provided by supervisors. On-site training is more expensive than training in larger clinics, but it has the advantage of requiring the trainee to identify potential users and deliver the method in their own setting, factors that probably support the institutionalisation of the service. Key components of the training should include family planning counselling, eligibility criteria (including the use of a checklist to rule out pregnancy), indications and contraindications. In Guatemala we also found that identification and management of STIs needed to be a component. of training.

Finally, nurse auxiliaries should be trained to implement community information activities to generate sufficient demand to justify the investment in training them. If appropriately conducted, this training does not lead to biased counselling in favour of the method being introduced. Simple measures like mentioning the availability of the new method or service to all women during their visits and at the end of health talks, as well as giving flyers to users to give to friends, have proved effective in generating demand.

To a large degree, the service statistics derived from the routine statistics management systems were often incomplete and not always reliable, for a variety of reasons. Hence, as much as possible we complemented these statistics with project-specific data collection, and tried to ensure the quality of the data by frequent supervision visits, training of service providers in data collection procedures and collection of data by project-specific interviewers and observers. Nevertheless, the limitations of the data obtained are acknowledged.

I would recommend that the training of nurse auxiliaries should be phased to include first those in health centres, and once IUD services are firmly established there, train the nurse auxiliaries in health posts. Health centres are located in larger towns with greater demand for services, and physicians and professional nurses there can help nurse auxiliaries to overcome their lack of confidence in their newly acquired skills. Lack of confidence was found to be a factor that prevented some providers from delivering services after completing their training. It was found to be essential also that to achieve certification, nurse auxiliaries needed to prove the existence of latent demand for the service in their communities by identifying women interested in using the method.

These studies also showed that nurse auxiliaries have no problem in assuming other reproductive health services such as the delivery of contraceptive injections or the taking of Pap smears. Although a study of the quality of Pap smears by trained nurse auxiliaries as compared to other trained providers taken should be carried out first, I would recommend that pending positive results, these tasks should also be shifted to these providers wherever possible.

Finally, another task that could probably be shifted to nurse auxiliaries would be the delivery of IUDs in the immediate post-partum period. The obstetric wards of small provincial hospitals in most low-income countries usually have a scarcity of physicians and obstetric nurses and an abundance of nurse auxiliaries. Although different, post-obstetric IUD insertion technique requires no greater skills than insertions in the interval period. Moreover, project and programme supervisors report that nurse auxiliaries in obstetric settings often have greater manual dexterity and experience. Training of nurse auxiliaries would make viable the establishment of post-abortion care and post-partum contraception programmes in these hospitals, which would greatly benefit women.

Acknowledgements

The work presented was made possible by the support of USAID's Cooperative Agreement No. HRN-A-00-98-00012-00 to the Population Council. The author acknowledges the valuable comments made by Ian Askew, Joanne Gleason and Patricia Stephenson on previous drafts, and editing support by John Townsend. Finally, my thanks for the invaluable conceptual contributions and project coordination and implementation of Rebecka Lundgren, Irma Mendoza and Yanira Villanueva in Honduras and of Carlos Brambila, Edwin Montufar and Jorge Solórzano in Guatemala.

Notes

* The authors of the different reports referenced were most involved in these studies; the first authors were the field coordinators from the local implementation agency. At the time these studies were conducted I supervised the Population Council's operations research in both countries. I helped design the projects and wrote the proposals and reports in collaboration with the other authors, except for the proposal and report of the first project in Honduras, which were written by Irma Mendoza and Rebecka Lundgren, and the diagnostic study in Guatemala, written by Carlos Brambila and Berta Taracena.

† All cost information presented refers to the periods in which the costs were incurred and the exchange rate into US dollars at the time.

* Discussions on the appropriateness of the delivery of family planning services by the Ministry of Health have been a frequent feature of Guatemalan elections and subject to changes by incoming presidential administrations since the late 1970s. While the 2004 incoming conservative administration crossed family planning off the list of programmes, they at least did not stop or prohibit the delivery of services altogether, as had happened in the past. When family planning services were dropped in past presidential transitions, they had to be re-installed with great effort, and assessments to determine whether or not to do so were not always impartial.

References

- L Ashford. Unmet need for family planning: recent trends and their implications for programs. Policy Brief. 2003; Population Reference Bureau/Measure Communication: Washington DC.

- Salem R. New attention to the IUD: expanding women's contraceptive options to meet their needs. Population Reports, Series B, No.7, February 2006.

- A Akin, RH Gray, R Ramos. Training auxiliary nurse-midwives to provide IUD services in Turkey and the Philippines. Studies in Family Planning. 11(5): 1980; 178–187.

- S Bang, SW Song, CH Choi. Improving access to the IUD: experiments in Koyang, Korea. Studies in Family Planning. 1(27): 1968; 4–11.

- NR Eren, R Ramos, RH Gray. Physicians vs. auxiliary nurse-midwives as providers of IUD services: a study in Turkey and the Philippines. Studies in Family Planning. 14(2): 1983; 43–47.

- Ministerio de Salud, Unidad de Salud de la Mujer. Normas de Atención Integral a la Mujer [Official Service Delivery Guidelines for the Integrated Care of Women]. 1995; Ministerio de Salud: Tegucigalpa, Honduras.

- Y Villanueva, L Hernandez, I Mendoza. Expansion of the Role of Nurse Auxiliaries in Offering Family Planning Services and Taking Vaginal Cytology Samples. INOPAL III Final Report. 1998; Population Council: Tegucigalpa, Honduras.

- FA Del Huezo. Report of the counseling study. 2000; EngenderHealth: Tegucigalpa, Honduras.

- Honduran Ministry of Health, Women's Health Unit. Norms and Procedures. Manual for Women's Integrated Care. Tegucigalpa, September 1999.

- Y Villanueva, I Mendoza, C Aguilar. Expansion of the Role of Nurse Auxiliaries in the Delivery of Reproductive Health Services in Honduras. FRONTIERS Final Report. 2001; Population Council: Washington DC.

- L Martinez. Evaluation of IUD insertions by nurse auxiliaries in Regions 1, 2 and 5. Consultancy Report. May. 2001; EngenderHealth: Tegucigalpa.

- Ministerio de Salud Pública y Asistencia Social, Guatemala. Encuesta Nacional de Salud Materno Infantil 2002 [National Maternal-Child Health Survey 2002]. Guatemala City, Guatemala, October 2003.

- C Brambila, B Taracena. Availability and acceptability of IUDs in Guatemala. Operations Research Final Report. September. 2002; Population Council: Guatemala City.

- E Montufar, C Morales, R Vernon. Improving access to long-term contraceptives in rural Guatemala through the Ministry of Health. FRONTIERS Final Report. 2005; Population Council: Washington DC.

- Ministerio de Salud Guatemala. Lineamientos Básicos y Políticas de Salud, Año 2004–2008. [Basic Health Guidelines and Policies, 2004–2008]. Guatemala City, October 2004.

- I Flores, ER Aguilar, RM Flores. Increasing use of the IUD through community and clinic based education activities in rural Honduras. FRONTIERS Final Report. 2007; Population Council: Washington DC.