Abstract

Women in sub-Saharan Africa are increasingly learning their HIV status in prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) programmes in the context of antenatal care. This paper examines women's decisions about HIV testing and their experience of PMTCT and HIV-related care in one clinic in Lilongwe, Malawi. It is based on qualitative, ethnographic research conducted in 2004 and 2005, including interviews and focus group discussions with 55 HIV-positive women participating in a PMTCT programme, and 21 interviews with key informants from the programme and the health system. Women's expectations from testing were consistent with the benefits for their own health and their infants' health, as communicated by nurses. However, the PMTCT programme only poorly met their expectations. Reasons for this disjuncture included the construction of women as still healthy even when they needed treatment, a focus only on infant health, health system weaknesses, lack of integrated care and timely referral, and defining HIV exclusively as a medical issue, while ignoring the social determinants of health. Women's own health was particularly marginalised within the PMTCT programme, yet good models exist for comprehensive care for women, infants and their families that should be implemented as testing is scaled up.

Résumé

En Afrique subsaharienne, de plus en plus de femmes connaissent leur statut sérologique grâce aux programmes de prévention de la transmission mère-enfant du VIH (PTME) dans le contexte des soins prénatals. Cet article examine les décisions des femmes sur le test et leur expérience de la PTME et des soins liés au VIH dans un dispensaire à Lilongwe, Malawi. Il est fondé sur une recherche qualitative ethnographique menée en 2004 et 2005 qui comprenait des entretiens et des discussions de groupe avec 55 femmes séropositives participant à un programme de PTME, et 21 entretiens avec des informateurs clés du programme et du système de santé. Les attentes des femmes quant au dépistage cadraient avec les avantages pour leur santé et celle de leur bébé tels que les infirmières les avaient exposés. Néanmoins, le programme de PTME répondait mal à leurs espérances, notamment du fait que les femmes se voyaient encore en bonne santé alors qu'elles avaient besoin d'un traitement. D'autres raisons étaient l'accent mis uniquement sur la santé du nourrisson, les faiblesses du système de santé, le manque de soins intégrés et de transfert ponctuel des patients, et la définition du VIH exclusivement comme une question médicale, au mépris des déterminants sociaux de la santé. La santé des femmes était particulièrement marginalisée dans le programme de PTME. Pourtant, de bons modèles de soins complets existent pour les femmes, les nourrissons et leur famille. Ils devraient être appliqués alors que le dépistage s'étend.

Resumen

Las mujeres en Ãfrica subsahariana están conociendo cada vez más su estado de VIH en programas de prevención de la transmisión materno-infantil (PTMI) del VIH, en el contexto de la atención antenatal. Este artículo examina las decisiones de las mujeres respecto a las pruebas de VIH y su experiencia con la PTMI y el tratamiento del VIH en una clínica de Lilongwe, en Malaui. Se basa en una investigación etnográfica cualitativa, realizada en 2004 y 2005, con entrevistas y discusiones en grupos focales con 55 mujeres VIH-positivas, que participaron en un programa de PTMI, y 21 entrevistas con informantes clave del programa y el sistema de salud. Las expectativas de las mujeres en cuanto a las pruebas concordaron con los beneficios para su propia salud y la salud de sus bebés, según informaron las enfermeras. Sin embargo, el programa de PTMI no logró satisfacer bien sus expectativas por las siguientes razones: ver a las mujeres como saludables aun cuando necesitaban tratamiento, centrarse sólo en la salud de los bebés, las debilidades del sistema de salud, la falta de servicios integrados y referencias oportunas, y definir al VIH exclusivamente como un problema médico sin prestar atención a los determinantes sociales de la salud. Aunque la salud de las mujeres fue particularmente marginada en el programa de PTMI, existen buenos modelos de atención integral para las mujeres, sus bebés y sus familias, que deberían implementarse según se vayan ampliando los programas de pruebas del VIH.

Increased availability of HIV interventions in resource-poor settings, including counselling and testing, antiretroviral therapy, and prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) programmes has resulted in a discursive shift in international and local health policy on HIV testing from the risks of testing to the benefits. While HIV interventions are still far from universally accessible in Africa, their availability, and the perceived individual and health systems benefits of testing, have led to greater promotion of HIV testing. One particular area of scale-up is in PMTCT programmes, where pregnant women are increasingly, and routinely, offered an HIV test.

Globally, vertical transmission of HIV is the most common cause of HIV infection in children under age 15. Without any intervention, 35% of infants will be infected: 15-20% during pregnancy, 50% during labour and delivery and 33% through breastfeeding.Citation1 While the World Health Organization promotes a comprehensive approach to the prevention of HIV in infants, including the health of mothers and families,Citation2 most programmes focus almost exclusively on PMTCT.

In PMTCT programmes in Lilongwe, Malawi, scale-up of HIV testing increasingly takes the form of routine, provider-initiated testing. Although this is contentious,Citation3–5 international agencies and local governments are making a concerted effort to recast HIV testing and are promoting testing outside the traditional parameters of voluntary counselling and testing:

“Because there was no antiretroviral treatment at that time and the cost was prohibitive, most people found that they couldn't answer the question, ‘Even if I get tested, then what?’…The risks of knowing your status outweighed your personal benefit. I think the international community, plus NGOs, human rights organizations, everybody really, by necessity played up the risks associated with knowing… Times have changed. HIV testing now becomes a gateway to benefits. You know, even in a poor country like Malawi, you can be treated. So, I think the international community is now making the transition from HIV testing as risk to HIV testing as a gateway to benefits.” (High-level policy official)

Concurrently, increased testing is seen as necessary in the push to reach HIV treatment targets.Citation6Citation7 Knowledge of one's HIV status is seen to reduce the spread of the virus, engage people in positive health choices, and facilitate health seeking behaviours, including accessing antiretroviral therapy. At a broader level, heightened visibility of HIV, and particularly healthy people living with HIV, are seen to break the silence and stigma of HIV, engender prevention and recast HIV as a normal disease.Citation8

The drive to expand HIV testing has increased the number of people accessing counselling and testing in Malawi each year since 2002 when 91,690 people were tested for HIV, of whom 5,059 were women in PMTCT programmes. In 2004, 221,071 people were tested for HIV, 43,345 of them women in PMTCT programmes.Citation9 However, due to a high rate of loss to follow-up, most infants did not benefit from the PMTCT programme. Of 6,069 pregnant women who tested HIV positive in Malawi that year, only 2,719 received take-home nevirapine. Information was not available on how many women and infants actually took it.Citation9 Data for 2006 from Lilongwe demonstrate that 45.4% of infants of HIV positive women did not receive nevirapine.Citation10

Moreover, most women are not yet obtaining the benefits of testing for their own health. In 2005, only 6.5% of Malawians in need of antiretroviral therapy were receiving it.Citation11 By 2007, access had improved and 35% of those with advanced HIV were receiving antiretroviral therapy.Citation12 Still, the potential benefits of testing are not inevitable outcomes,Citation7,13–15 but will depend on adequate counselling, scale-up of treatment and care, and health systems strengthening and coordination.

In this paper, I draw on ethnographic research on the importance that women in Lilongwe, Malawi, give to an HIV test in settings of increased intervention. A focus on the experiences of service users is important, as their goals and motivations often differ from the perspectives of those who create and deliver services.Citation16–18

Methodology

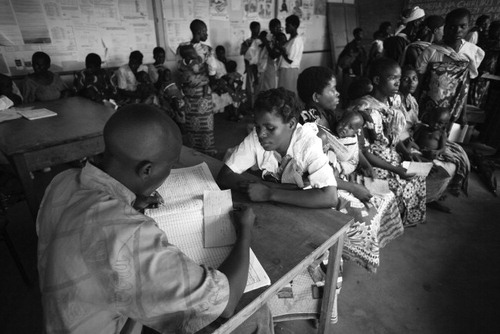

The data reported here are part of a larger ethnographic study of the creation and delivery of a PMTCT programme, how women understand and make decisions about participation, and the meaning of HIV diagnosis in women's lives and social world. Data were gathered between August 2004 and June 2005 through interviews, focus group discussions (FGDs), and observation at a clinic of health talks, group counselling sessions and women's flow through the PMTCT programme and health centre.

Thirty-four women were recruited from the clinic's PMTCT programme after an HIV positive diagnosis for individual interviews. In the post-test counselling session, nurses asked women found HIV positive if they would be willing to speak to my research assistant and me about participation in a study that involved talking about HIV. During recruitment, we explained the project to the first one or two women found HIV positive each day. The women who agreed participated in up to six interviews, which were scheduled to coincide with processes in the PMTCT programme and their antenatal visits. The interview schedule followed women through their experience in the PMTCT programme and the health services at each stage, to examine the changing meaning for them of HIV as time passed after their diagnosis and in relation to self, family, and community. The first interview followed HIV diagnosis; the second occurred when women received infant feeding counselling and their dose of take-home nevirapine at 36 weeks gestation; the third was scheduled shortly after birth; the forth coincided with HIV testing of the infants at six weeks of age; the fifth took place when women were to receive their infants' test results; and the sixth, a life history interview, was scheduled to fill otherwise lengthy gaps between meetings. Due to length, the life history interview was sometimes broken into two parts.

A series of FGDs were conducted with 21 other women, in groups of four to six women each, recruited from a post-natal support group run by the PMTCT programme. The women, whose children were 4–19 months old, had been participating in the PMTCT programme longer than the women who had individual interviews. To recruit them, I made a presentation about the research at one of the group's monthly meetings; all the women who expressed interest were invited to participate. The four FGDs covered current issues and concerns about life with HIV and the PMTCT programme.

Twenty-one key informant interviews were also conducted with nurses from the PMTCT programme, community nurses and government nurses and other medical staff; PMTCT programme architects and managers; government policymakers; and relevant officials in multilateral and bilateral aid agencies.

All research participants were fully informed of the study and consented to participate. This study was approved by McMaster University Canada's Research Ethics Board, Malawi's National Health Sciences Research Committee, and the Lilongwe District Health Office.

All interviews and FGDs were semi-structured and designed to elicit participants' own views and understanding. Interviews and FGDs with women in the PMTCT programme were conducted in Chichewa. During the interviews and FGDs translation between English and Chichewa was done by a Malawian research assistant. Key informant interviews were in English. All interviews and FGDs were tape recorded, transcribed, and translated into English if necessary. The simultaneous translation in interviews and FGDs served to verify the translation, as any mistranslations became apparent. The written translations were checked against the tapes. Transcripts were thematically coded using QSR N6, a qualitative data analysis programme.

The PMTCT programme and HIV testing

PMTCT programmes were first set up in Malawi in 2001, and have predominantly been delivered by non-governmental organizations. This was the case at the PMTCT programme where this study was conducted, which was delivered as a separate programme at the government health centre where general antenatal care was provided.

All antenatal care attendees received a general health talk in the courtyard of the health centre. The nurses gave information on general disease prevention, hygiene, care for common illnesses, child spacing, delivery, HIV, the PMTCT programme and the benefits of HIV testing.

“Nurse: What is the benefit of having a test?

Woman: The goodness is you know how you are in your body.

Nurse: The benefit is you know your status and you receive counselling on how to prolong your life: what foods to eat, what to do in order not to increase the virus, how you can protect others, and also how you can prevent your unborn baby. Those found negative are also advised on how to live so that they don't catch the virus.”

Women became well versed in the topics and the health promotion songs sung after the talk. First time attendees, as well as those not previously tested, were invited to the adjacent PMTCT programme veranda for a further talk on PMTCT and HIV counselling and testing.

Those who accepted an HIV (rapid) test had post-test counselling and their first antenatal care from the PMTCT programme. After that, all women, whether HIV positive or negative, had their monthly antenatal visits with nurses and midwives in the government clinic. HIV positive women were thus not in monthly contact with the PMTCT programme and only returned there at 36 weeks gestation for infant feeding counselling and a single nevirapine dose. In 2005, the nevirapine dose began to be administered at the post-test counselling session. Health centre deliveries were attended by government midwives, and a single dose of nevirapine was supposed to be given to newborn babies upon delivery. If this did not occur or if women delivered elsewhere, women were to present at the PMTCT programme for the infant dose. Post-natally, women were invited to join a monthly support group there. This structure meant that women were made responsible for navigating between the PMTCT clinic and the government clinic, which contributed to loss to follow-up.

PMTCT programme staff were supposed to provide treatment for minor illnesses and refer women to the government outpatient department or tertiary medical facilities if needed. The programme continued to follow women diagnosed with HIV and their infants for 18 months after birth, when they were discharged from care. They were not referred for further HIV-related care unless they were assessed as eligible to begin antiretroviral treatment.

Testing decisions

In 2004, 82% of the 4,517 women attending this PMTCT programme agreed to be tested for HIV. In 2005, the PMTCT programme changed from an opt-in to an opt-out system of testing. That is, from a protocol in which women volunteered for HIV testing after counselling to automatic testing unless they explicitly declined. All women interviewed for this study were tested under the opt-in policy. The information communicated by the nurses on the benefits of testing was apparent from what women said about testing decisions.

Knowing is better than not knowing

Explicit within the stories women communicated in interviews and FGDs was a basic desire to know, a belief that it is good to know one's HIV status, and that with knowledge they could make decisions.

“It's better to know, rather than living in doubt not knowing where you stand. Because it can be possible that you don't have the virus. And, in the process, you can get it. Or, if you have it, it can keep multiplying.” (Anne, Interview 5)

“Nowadays, people will just be staying not knowing that there is something in their body. So I decided to have my blood tested to see what to do later.” (Sandra, Interview 1)

Health benefits and concerns

Women described both the communication about testing and pre-existing health concerns as motivating them to learn their HIV status. Importantly, HIV testing was seen as just one component of a comprehensive health package with benefits for their own health and health care seeking as well as their babies:

“I was motivated… because the nurse said it is important for pregnant women to have a test because, once found positive, there is a prevention for the baby.” (Agnes, Interview 1)

“I wanted them to check me if I had diseases, like warts or syphilis, because they say the baby comes with stuff in the eyes. So that's why I had a test.” (Patricia, Interview 4)

“I just decided to see what is wrong in my body, because it's different now as compared to before.” (Grace, Interview 1)

“I wanted to know if I had the virus, and that, if I have it, I should receive counselling on how I can prolong my life.” (Mary, FGD 1)

“I wanted to know, because sometimes nowadays people just suffer from different diseases like malaria, cough, pneumonia, diarrhoea… And you will find that you are accusing people of witchcraft, not knowing that you have HIV… So every time I fall sick, I will always rush to the hospital to receive treatment.” (Patricia, Interview 1)

“…on the radio they were announcing that there is help for people found with that problem [HIV]. So I wanted to be tested so that, if there was a problem, I should be assisted as others have been assisted.” (Martha, FGD 3, Discussion 4)

Feeling vulnerable

Many women reported general feelings of vulnerability to HIV. Some of them had intended to have an HIV test before they got pregnant but did not, often due to disputes with their husbands. The PMTCT programme allowed them to be tested.

“The one I was staying with [my brother] is the one who advised me… I told [my future husband] that we should go for a test together, but he refused.” (Joyce, Interview 1)

“Even if I had not fallen pregnant, I would still have found a chance to go for a test, because I was scared with my first husband's behaviour.” (Claire, Interview 1)

“… ever since I got married to my husband, I have been faithful to him. But I feel that sometimes he is not faithful to me.” (Sarah, Interview 1)

Most women reported having partners prior to their present relationship (either previous husbands or boyfriends). However, when they spoke about their initial reasons for testing they attributed feelings of risk and vulnerability to their awareness or lack of awareness of their husbands' sexual history and sexual lives outside the home, or knowledge that their husbands had other partners.

Other women recognised conditions or situations that they felt increased their risks and saw deaths within their sexual networks as reasons to test.

“Because they say that one can get the virus if they have had STIs. So, because I once had an STI with my first husband, that's why I thought I should have a test.” (Nancy, Interview 1)

“This year, I learned that one of his [husband's] previous wives had died. And, the way she suffered, she must have died of AIDS. So, from that time, it's when I started thinking that, in that case, we are all infected.” (Anne, Interview 1)

Barriers to the achievement of testing benefits

Women's own health was a major motivating factor in their uptake of HIV testing. PMTCT programmes, however, were not achieving their full potential in both preventing vertical transmission and addressing women's own health needs. I identified five barriers in this regard:

• Women constructed as “still healthy”

At the time of this study, the nurses often constructed women with an HIV positive diagnosis as “still healthy” because they were asymptomatic. Hence, they were often not referred for HIV care. Yet they did not know the women's actual health status, as CD4 count and viral load testing were not yet being done within the programme. Since 2006, women testing positive have been able to have routine CD4 count testing as a component of the PMTCT programme, and those with CD4 counts below 250 are referred for antiretroviral treatment.Citation19 This is a significant step forward. Indeed, the situation in 2004 and 2005 showed the importance of this assessment, as the women did often appear to be in good health, which could mask serious problems. For example, Teresa, an FGD participant, said that although she felt healthy, in a biomedical study in early 2004 she was found to have a CD4 count of 154, denoting a severely compromised immune system. Teresa had not yet been referred for treatment, even though antiretroviral therapy had become freely available by the time I met her.

In fact, despite appearances, the women often had coughs, diarrhoea, fevers, malaria and skin rashes, and could have been treated in the PMTCT programme where their HIV status was known, rather than in the general outpatient department where their HIV status was not known, which they could disclose or not. Most of the women interviewed accepted the PMTCT programme staff's assessments of their health, regardless of their own perceptions. This highlights the primacy often given to expert knowledge over subjective experience. However, some were dissatisfied.

“When I came for antenatal, I was told that the virus hasn't yet started in my body, but it will start. [But], as for me, in my own thinking, I think the virus has already started but, because of my pregnancy, maybe they didn't want to disappoint me. But the way I feel myself, I continuously get ill – diarrhoea two to three times a month – so I just feel they have hidden it from me. But I told them just to tell me the truth.” (Frances, Interview 1)

• Focus on infant health

Despite the WHO guidelines on comprehensive PMTCT programmes, in practice these programmes exemplify the fragmentation of health care and the lack of comprehensive and integrated approaches. There was a disjuncture between the messages on the benefits of testing for women's own health and the possibilities of care for them within the PMTCT programme and the health system more generally. As has been shown, women described their own health and care that will prolong their lives as a primary concern in accepting a test. Preventing HIV in their children became a concern after a positive test result, when their own HIV status became relevant to their child's health. Women, however, often received care only on behalf of their children, continuing a tradition of viewing women both as vessels and vectors of HIV transmission, i.e. reservoirs of infection and those responsible for transmitting it, as well as solely through their reproductive function.

Women's care seeking was often prolonged. Many described first seeking care at the PMTCT programme when they were sick. Indeed, this was the care-seeking rhythm advised by PMTCT programme staff: that PMTCT programme staff would attend to the health complaints of women and babies registered in the programme. In reality, however, women often waited to see the nurses there only to be referred to the government outpatient clinic. The women found this process frustrating and time-consuming. Given their HIV status and pregnancy, they found it too laborious to stand in long queues and crowded hallways waiting for care.

“There is no assistance. When you go there with a problem [PMTCT], they tell you that you should go to the government side, saying the problem is beyond their capacity. And, when you go to that side, you will find a long queue and you are not assisted. So I feel it's not good for them to be telling us to come to the programme. It is better we go there [government outpatient clinic] as ordinary people. They told us that, after we were found with this problem, they will take care of us, but they don't meet our needs. So it's better they don't tell us to go there, because there is no help at all.” (Jane, FGD 2)

“We people are already weak so, if we stand in a queue for a long time, we can easily fall or be pushed.” (Martha, FGD 3)

• Health system weaknesses

There were numerous health system weaknesses that limited the quality of care for women living with HIV. Drug shortages in the public health service were a significant problem for women without the money to buy the drugs themselves. When women's attempts to access care took them to multiple clinics, transportation and the cost of services at private hospitals were burdensome:

“There was a time I came and was sent back. The other day, I came again with my child. They told me to stop coming here [PMTCT programme], saying I should be going to that side [government]. I felt bad, because there were no drugs. I came again, but still it was the same thing. So, I just decided to go to [a different government] health centre myself, and there I was assisted.” (Melissa, FGD 4)

“If you stay far away from the health centre, you have to go to a private hospital. But if you don't have money, you will continue falling sick, and normally these government hospitals don't assist you.” (Beth, FGD 2)

Inadequate funding and staff shortages were also a major strain. At the health centre where this PMTCT programme was based, 300—400 patients visited the outpatient department each day. The clinical officer and medical assistant reported that they were only able to spend a few minutes with each patient. They described the stress and burnout that resulted and their frustration at not being able to provide better care. This is a systemic problem in Malawi:

“There is a crisis situation within the Ministry of Health. Health centres are closing, because there are no people to staff the facilities. Vacancies in some categories of workers within the Ministry range from 50—100%, and if you're going to be able to scale-up testing and treatment to 50,000 Malawians, you need health workers. It's very simple.” (High-level policy official)

Even after individuals were referred for antiretroviral therapy, congestion caused significant delays in initiation of treatment. People often waited several months before they could be evaluated for antiretroviral therapy eligibility.

• Lack of integrated care

Continuity of care between the PMTCT programme and other care is critical if women are not to fall in the gaps between services. Even at the same health centre, PMTCT and government antenatal, delivery and outpatient care were provided separately. Moreover, antiretroviral therapy, though freely available, was provided at a separate site. In the PMTCT programme, women had countless questions about drugs to treat HIV, how to access them and where. Many women were not even aware that antiretroviral therapy was available in Malawi or free. Some thought the CD4 test must be paid for and was expensive. The interviews and FGDs demonstrated that women actively sought information.

“My only hope is that life-prolonging drugs can be available. Then I will be able to care for my kids.” (Patricia, Interview 4)

“I just want to know what way we should take when we start falling sick and becoming weak?” (Mercy, FGD 3)

Such questions were surprising, as they came from women actively engaged in the PMTCT programme protocol who should have received this essential information.

Knowing how to get onto antiretroviral therapy was important, as existing referral systems did not effectively facilitate timely access. Women who left the PMTCT programme without a referral for antiretroviral therapy assessment had even grimmer prospects than those in the programme, as they were more likely to get lost in the gaps. PMTCT programme staff understood that vertical programming and poor integration between services limited quality of care. They nonetheless define their mandate narrowly, as they see these as systems issues beyond their direct purview, due to resource limitations:

“When a woman is at the end of her programme or involvement with us, if she has not reached the point where her clinical symptoms indicate she should be referred [for antiretroviral therapy], you know there is a risk that she won't recognize or may not have regular contact with the health care system and may not be referred appropriately and may not seek care in a timely manner. That's clearly a risk. It's not something we can directly do something about, other than to continue to work with the district health centres and the [District Health Office] and the Ministry to work with the scale-up programme, which we're doing… The reality is, every now and then, you run into a limit. You can do this, but not more than that.” (A PMTCT programme director)

Unfortunately, women feel abandoned when their care finishes and they have no clear prospects for comprehensive care elsewhere.

• Defining HIV exclusively as a biomedical issue

The biomedical paradigm within which the programme was offered compounds other constraints. In defining HIV exclusively as a medical issue, the PMTCT programme staff focused on medical treatments. However, the success of medical treatments depends also on the ability to address psychosocial and education issues, poverty, transportation and food insecurity.

PMTCT programme nurses said they did not have enough time to counsel each woman adequately and needed more time. The information they have to give is complicated and while they tried to present it in a non-scientific way, it often contradicted what women believed. For example, many women found it confusing that their babies could be born without HIV because they thought that mother and baby shared the same blood and that sperm contained HIV, neither of which is the case. Lack of understanding limited their engagement in the programme. Moreover, inadequate counselling failed to prepare them to cope with their HIV diagnosis with their partners, families and communities.

Limited economic resources also limited women's capacity to attend to their own health and adhere to the PMTCT programme protocol. Women who were referred to the government-run tertiary care facility for specialised treatment found transportation a significant and sometimes impossible expense.

“Everything needs money. To go to the hospital… we need transport. Because we cannot go on foot to central hospital, so that also is a problem.” (Beth, FGD 2)

Food insecurity emerged as a major challenge for women trying to follow the positive living advice to eat a balanced diet to keep their immune systems healthy.

“Mainly, my concerns come when I want something to eat, and I can't get it… And I begin to worry and ask myself if I am going to live longer.” (Anne, Interview 1)

The success of PMTCT and other HIV interventions will depend on the capacity to address all these problems.

Conclusions

New international health and treatment targets are predicated on individuals knowing their HIV status. At this local PMTCT site, nurses told women that if they learned their HIV status, there was an intervention to prevent HIV transmission to the child, and that women themselves could prolong their lives. This is a compelling testing message. Unfortunately, the existing paradigm of the PMTCT programme meant that women faced numerous barriers in achieving these goals. The way in which PMTCT programmes were offered follows on from maternal and child health programmes, which have long focused only on infants and considered women, if at all, in relation to improving infant outcomes.Citation20Citation21 Women's own health was particularly marginalised within the PMTCT programme, yet good models exist for comprehensive care for women, infants and their familiesCitation22–24 that should be implemented as testing is scaled up. Adding support services and integrating with other health services would move the PMTCT programme beyond its focus on infants alone to encompass women's health, recognising that infant survival often hangs in the balance.

These problems are not specific to the PMTCT programme, but are related to general weaknesses in the entire health system. In Malawi, as elsewhere in Africa, donor-funded vertical programmes operate in the midst of a crumbling public health care system.Citation25 Indeed, they often contribute to the deterioration of the public health system insofar as they divert financial and human resources from the government health sector when they could be feeding funds through it.Citation26Citation27 The current patchwork of services places an undue burden on those requiring care to seek it at multiple sites. While there is a growing focus on the importance of continuous and integrated care, which recognizes the failure of vertical programmes, and the importance of social determinants of health, these theoretical and policy shifts have been slow to materialize in programmes.

Acknowledgements

My foremost thanks go to the women in Lilongwe who generously shared their experiences, and all those who kindly facilitated my research there. Special thanks to my research assistant Cynthia Zulu. The research was funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Institute of Gender and Health Doctoral Research Award and a McMaster University School of Graduate Studies Field Research Grant. I thank my doctoral committee members, Dr Dennis Willms, Dr Wayne Warry, and Dr Karen Trollope-Kumar, for their advice on research and my PhD dissertation, on which this work draws. Parts of this work were previously presented at the 16th International AIDS Conference and the Society for Applied Anthropology/Society for Medical Anthropology Meetings in 2008. Current support is through a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Post-doctoral Fellowship. I thank my post-doctoral supervisor Dr Daniel Sellen.

References

- UNICEF. Prevention of Parent-to-Child Transmission of HIV/AIDS. New York, 2006.

- World Health Organization. Mother-to-child transmission of HIV. 2006. At: <www.who.int/reproductive-health/stis/mtct/index.htm. >. Accessed 26 May 2006.

- J Csete, R Elliott. Scaling up HIV testing: human rights and hidden costs. Canadian HIV/AIDS Policy and Law Review. 11: 2006. 1,5–10.

- J Csete, R Schleifer, J Cohen. “Opt-out” testing for HIV in Africa: a caution. Lancet. 363: 2004; 493–494.

- M Heywood. Human rights and HIV/AIDS in the context of 3 by 5: time for new directions?. Canadian HIV/AIDS Policy and Law Review. 9: 2004. 1,7–12.

- S Rennie, F Behets. Desperately seeking targets: the ethics of routine testing in low-income countries. Bulletin of WHO. 84: 2006; 52–57.

- S Kippax. A public health dilemma: a testing question. AIDS Care. 18: 2006; 230–235.

- Ministry of Health. Voluntary Counselling and Testing: Site Counsellor's Handbook for Malawi. 2nd ed., 2004; Ministry of Health: Lilongwe.

- National AIDS Commission. Report of a Country-Wide Survey of HIV/AIDS Services in Malawi for the Year 2004. 2005; National AIDS Commission: Lilongwe.

- A Moses, C Zimba, E Kamanga. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission: program changes and the effect on uptake of the HIVNET 012 regimen in Malawi. AIDS. 22: 2008; 83–87.

- Libamba E, Makombe S, Harries A, et al. Antiretroviral therapy scale up in Malawi. National HIV and AIDS Research and Best Practices Conference. Lilongwe, 2005.

- UNAIDS. 2008 Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. 2008; UNAIDS: Geneva.

- J Matovu, R Gray, F Makumbi. Voluntary HIV counselling and testing acceptance, sexual risk and HIV incidence in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS. 19: 2005; 503–511.

- D McCoy, M Chopra, R Loewenson. Expanding access to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: avoiding the pitfalls and dangers, capitalizing on the opportunities. American Journal of Public Health. 95: 2005; 18–22.

- T Painter. Voluntary counselling and testing for couples: a high-leverage intervention for HIV/AIDS prevention in sub-Saharan Africa. Social Science and Medicine. 53: 2001; 1397–1411.

- RP Petchesky. Re-theorizing reproductive health and rights in light of feminist cross-cultural research. C Obermeyer. Cultural Perspectives on Reproductive Health. 2001; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 277–299.

- M Inhorn. Defining women's health. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 20: 2006; 345–378.

- E Bell, P Mthembu, S O'Sullivan. Sexual and reproductive health services: perspectives and experiences of women and men living with HIV and AIDS. Reproductive Health Matters. 15(29 Suppl): 2007; 113–135.

- Mofolo I, Kamanga E, Martinson F, et al. PMTCT program progress at University of North Carolina Project, Lilongwe, Malawi. XVII International AIDS Conference. Mexico City, 2008.

- A Rosenfield, E Figdor. Where is the M in MTCT? The broader issue in mother-to-child transmission of HIV. American Journal of Public Health. 91: 2001; 703–704.

- A Rosenfield, D Maine. Maternal mortality - a neglected tragedy: where is the M in MCH?. Lancet. ii: 1985; 83–85.

- E Abrams, L Myer, A Rosenfield. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission services as a gateway to family-based human immunodeficiency virus care and treatment in resource-limited settings: rationale and international experience. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 97: 2007; S101–S106.

- T Sripipatana, A Spensley, A Miller. Site-specific interventions to improve prevention of mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus programs in less developed settings. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 197: 2007; S107–S112.

- A Furber, I Hodgson, A Desclaux. Barriers to better care for people with AIDS in developing countries. BMJ. 329: 2004; 1281–1283.

- D Palmer. Tackling Malawi's human resource crisis. Reproductive Health Matters. 14: 2006; 27–39.

- J Pfeiffer. International NGOs in the Mozambique health sector: the “velvet glove” of privatization. A Castro, M Singer. Unhealthy Health Policy: A Critical Anthropological Evaluation. 2004; AltaMira Press: Walnut Creek, CA, 43–62.

- H Schneider, D Blaauw, L Gibson. Health systems and access to antiretroviral drugs for HIV in southern Africa: service delivery and human resources challenges. Reproductive Health Matters. 14: 2006; 12–23.