Abstract

Medical abortion has the potential to increase the number, cadre and geographic distribution of providers offering safe abortion services in India. This study reports on a sample of family planning providers (263 mid-level providers, 54 obstetrician-gynaecologists and 88 general physicians) from a 2004 survey of health facilities and their staff in Bihar and Jharkhand, India. It identified factors associated with mid-level provider interest in training for early medical abortion provision, and examined whether obstetrician-gynaecologists and general physicians supported non-physicians being trained to provide early medical abortion and what factors influenced their attitudes. Findings demonstrate high levels of mid-level provider interest and reasonable physician support. Among mid-level providers, being male, having a more permissive attitude towards abortion and current provision of abortion using any pharmacological drugs were associated with greater interest in attending training. Mid-level providers based in private health facilities were less likely to show interest. More permissive attitude towards abortion and current medical abortion provision using mifepristone-misoprostol were inversely associated with obstetrician-gynaecologists' support for non-physician provision of medical abortion. General physicians based in private/other health facilities were less supportive than those in public facilities. Study findings strengthen the case for policymakers to expand the pool of cadres that can legally provide safe abortion care in India.

Résumé

L'avortement médicamenteux peut accroître le nombre, le type et la distribution géographique des prestataires de services d'avortement médicalisé en Inde. Cette étude porte sur un échantillon de prestataires de planification familiale (263 cadres moyens, 54 gynécologues-obstétriciens et 88 médecins généralistes) interrogés pour une enquête de 2004 sur les établissements de santé et leur personnel au Bihar et Jharkhand, Inde. Elle a répertorié les facteurs associés avec l'intérêt des cadres moyens pour une formation à l'avortement médicamenteux précoce et a examiné si les gynécologues-obstétriciens et les médecins généralistes soutenaient la formation de non-médecins à ces services et quels facteurs influençaient leurs attitudes. Les conclusions montrent des niveaux élevés d'intérêt de la part des cadres moyens et un soutien raisonnable des médecins. Le fait d'être un homme, d'avoir une attitude plus permissive à l'égard de l'avortement et de pratiquer des avortements pharmaceutiques était associé à un plus grand intérêt des cadres moyens pour la formation. Les cadres moyens basés dans des établissements privés avaient moins de probabilités d'être intéressés. Une attitude plus permissive à l'égard de l'avortement et la pratique d'avortements avec la mifépristone et le misoprostol était inversement associée au soutien que les gynécologues-obstétriciens apportaient à la pratique d'avortements médicamenteux par des non-médecins. Les médecins généralistes basés dans des établissements privés ou autres étaient moins favorables que ceux des centres publics. Les conclusions de l'étude confirment que les décideurs doivent élargir le groupe de prestataires qui peuvent légalement pratiquer des avortements médicalisés en Inde.

Resumen

Los servicios de aborto con medicamentos tienden a aumentar el número, tipo y distribución geográfica de prestadores de servicios de aborto seguro en la India. Este estudio informa sobre una muestra de proveedores de planificación familiar (263 de nivel intermedio, 54 gineco-obstetras y 88 médicos generales), de una encuesta realizada en 2004 con personal y establecimientos de salud en Bihar y Jharkhand, en la India. Se identificaron los factores asociados con el interés de los profesionales de nivel intermedio en recibir capacitación en la prestación de servicios de aborto con medicamentos temprano, y se examinó si los gineco-obstetras y médicos generales apoyaban la capacitación del personal no médico en estos servicios, así como los factores que influyeron en sus actitudes. Los resultados demuestran altos niveles de interés por parte de los prestadores de nivel intermedio y considerable apoyo de los médicos. Entre los prestadores de nivel intermedio, ser hombre, tener una actitud más permisiva hacia el aborto y proporcionar servicios de aborto con fármacos, se asociaron con mayor interés en la capacitación. Los prestadores de nivel intermedio en establecimientos privados tendían a mostrar menos interés. Las actitudes más permisivas hacia el aborto y la práctica de abortos con mifepristona-misoprostol estaban asociadas inversamente con el apoyo de los gineco-obstetras a la práctica de abortos con medicamentos por personal no médico. Los médicos generales en establecimientos privados brindaron menos apoyo que aquéllos en establecimientos públicos. Estos resultados confirman que los formuladores de políticas deben ampliar el grupo de prestadores de servicios de aborto seguro y legal en la India.

The 1971 Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act greatly liberalized the social and medical conditions in which women in India may access safe abortion services. However, access remains difficult due to factors such as the limited availability of trained providers, especially in rural areas, where three-quarters of the population live. Rural areas are served largely by untrained or inadequately trained providers. Even where licensed facilities exist, they may not provide abortions because of lack of equipment and supplies or a lack of trained providers.Citation1–8 Current abortion policy in India excludes non-physicians from being trained as abortion providers. Only registered physicians meeting specific training and experience requirements at hospitals or clinics approved by the government may legally provide abortion services.Citation9 Annually, an estimated 450 maternal deaths occur per 100,000 live births in India.Citation10 Unsafe abortion is a significant cause of these deaths, accounting for an estimated 9–20% of the total.Citation1,11–14 To help solve the problem of unsafe abortion, the World Health Organization recommends increasing the numbers of properly trained and adequately equipped personnel, using proven abortion methods and providing abortion services at the lowest appropriate level of the health care system.Citation15 Interest in involving mid-level health care providers in a variety of medical roles, including in abortion provision, has been increasing worldwide.Citation16 Mid-level providers include a wide range of non-physicians (physician assistants, nurses, midwives and others) who differ in training and responsibilities from country to country but carry out clinical procedures, including those related to reproductive health.Citation15 In most regions of the world, mid-level providers outnumber physicians; they often work in closer proximity to where women live and can often offer more affordable services.Citation15–18

Medical abortion using mifepristone and misoprostol is safe and effectiveCitation11,19–22 and was approved by the Drug Controller of India in 2002 up to 49 days of pregnancy.Citation23 In a country like India, where abortion-related morbidity and mortality are high and the health infrastructure can limit access to safe aspiration abortions, medical abortion could greatly improve safety and access by increasing the number, cadre and geographic distribution of health care providers who can be trained.Citation24Citation25 Medical abortion does not require extensive infrastructure. In addition to mid-level provider interest and the necessary policy changes, an enabling environment, including the support of physicians, is critical.

Many mid-level providers already do abortions in response to community demand.Citation26–28 However, little evidence exists on their interest in being trained to offer medical abortion services or on the views of physicians about their doing so.Citation23,29–32 A study in Bihar and Jharkhand in 2004, conducted around the same time as data for the current study were collected, and a 2003 survey of members of the Federation of Obstetric and Gynaecological Societies of India both found that the majority of obstetrician-gynaecologists knew about mifepristone-misoprostol and reported providing abortions using one or both drugs.Citation23Citation33 Few general physicians or other types of health care providers in Bihar and Jharkhand have reported providing mifepristone-misoprostol.Citation33Citation34 A 2005 qualitative study from south India found that 12 of 37 private sector physicians who participated in the study and who provided abortions were providing medical abortion services; village health nurses interviewed said they had no knowledge of medical abortion.Citation32

Bihar in India was divided into two states, Bihar and Jharkhand, in 2000. Nearly 85% of the population in Bihar and 75% in Jharkhand live in rural areas.Citation35Citation36 Both states have relatively poor socio-economic and health indicators compared to other states in India, including high rates of poverty, illiteracy and infant and child mortality.Citation35–37 They also have relatively high total fertility rates, high unmet need for family planning and low numbers of deliveries in medical facilities.Citation35Citation36 Furthermore, both states have high estimated rates of abortion, but limited approved facilities offering abortion services.Citation1,33

This study aimed to assess the environment for mid-level providers to participate in early medical abortion provision in Bihar and Jharkhand, including factors associated with mid-level provider interest in training for early medical abortion, the attitudes of obstetrician-gynaecologists and general physicians towards them doing so and the factors that influenced their attitudes.

Methodology

The data come from a larger project which sought to assess the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of clinic-franchising programmes in improving the delivery of family planning services and use of contraception in Bihar and Jharkhand.Citation38 The project applied a multi-stage cluster sample design to the entire area making up the current two states (except for some districts that were unsafe for fieldwork) to obtain samples of governmental, non-governmental (NGO) and private health facilities providing family planning services and their clinical staff.Citation38Citation39 Large hospitals with more than 50 beds were excluded.Citation38 The surveys of health facilities and their staff were piloted and carried out between May and August 2004.

Health facility heads were approached by a pair of male and female field interviewers for consent. All staff in the facilities were enumerated; all those who were authorized to provide family planning services and who consented to participate were interviewed. The achieved sample included 1,346 health facilities and 2,039 staff providing family planning. The response rate for providers was 84%. Heads of health facilities were interviewed about the types of reproductive health services offered and the number, type and service capacity of their staff. The staff questionnaire covered socio-demographic characteristics, services offered by the provider, training experience and referral behaviour. A separate medical abortion module was developed and added to the health facility staff questionnaire for this study.

To assess the mid-level providers' interest in attending mifepristone-misoprostol training for early abortion, we asked them: “If a seminar or training on mifepristone and misoprostol for early abortion were offered in the future, would you be interested in attending? (yes/no)”. To assess the obstetrician-gynaecologists' and general physicians' attitudes towards non-physicians being trained for this, we asked them: “Should health care providers other than physicians be eligible to be trained and to provide early medical abortion? (yes/no)”.

Family planning provider explanatory variables included: attitude towards abortion, current abortion provision or help with abortion provision using mifepristone-misoprostol, current abortion provision using any pharmacological drugs and sex of provider. Health facility explanatory variables were: type of health facility where the provider worked, obstetrician-gynaecologists and general physicians on staff at the health facility, and mid-level providers on staff at the health facility. Not all explanatory variables were included in every analysis.

Attitude towards abortion was measured by asking: “Under which of the following (ten) conditions or situations do you personally believe a woman should be able to have an induced abortion?” Seven “yes” answers (the modal score) were labelled as a “permissive” attitude, fewer than seven as “less permissive” and more than seven as “more permissive”. All family planning staff were asked whether they provided or helped to provide any kind of abortion services, and if yes, which ones (manual or electric vacuum aspiration, D&C and medical abortion using mifepristone-misoprostol). The measure, current abortion provision or help with abortion provision using mifepristone-misoprostol (yes/no) was created from this question. All providers were also asked: “Do you currently use any pharmacological drugs in your practice to induce abortions?”. This question was used to create the two-category measure, current abortion provision using any pharmacological drugs (yes/no). Sex of provider (male/female) was noted by the interviewers.

The type of health facility where the provider worked was categorized as a government, private facility, or other facility (franchised NGO facilities, NGO facilities and private unqualified health clinics). All heads of health facilities were asked what type of and how many clinicians provided family planning services at their facility. The measures obstetrician-gynaecologists and general physicians on staff (yes/no) and mid-level providers on staff (yes/no) were created from responses to this question.

Data were analyzed using Stata 9.2; all analyses were weighted and adjusted to account for the clustered sampling design. Three sub-populations were created for analysis: mid-level providers (unweighted n=263), obstetrician-gynaecologists (unweighted n=54) and general physicians (unweighted n=88). Mid-level providers in this study included auxiliary nurse midwives (ANMs), lady health visitors (LHVs), male health workers (MHWs), nurses and paramedics. In India, ANMs, LHVs, and MHWs work at government facilities only, have completed at minimum 10 years of schooling plus a diploma course and are responsible for providing family planning and preventive services, referrals, keeping records and treating minor ailments. Nurses and paramedics work at a variety of health facilities, usually have a college degree and assist physicians in taking care of patients and carrying out tasks such as administering medication, changing dressings and preparing patients for surgery. In this study, obstetrician-gynaecologists included physicians who reported that they had an MD/MS/DNB in Obstetrics and Gynaecology or a Postgraduate Diploma in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. General physicians were doctors who stated they had an MBBS degree.

Bivariate analyses using logistic regression examined associations between mid-level providers' interest in attending training for early medical abortion and selected provider and health facility variables. Multivariate logistic regression was used to assess the association between mid-level providers' interest in attending medical abortion training and the variables sex of provider, attitude towards abortion, current abortion provision using any pharmacological drugs, type of health facility where they worked, and whether there were obstetrician-gynaecologists and/or general physicians on staff at their health facility. The model controlled for mid-level provider age (years), education (primary/secondary/completed secondary or more), and health facility location (urban/rural).

Bivariate analyses examined associations between selected provider and health facility variables and physicians' attitudes towards non-physicians being trained to provide early medical abortions. Two separate logistic regression models, one for obstetrician-gynaecologists and one for general physicians, estimated the relationship between attitude towards non-physician training and the variables: attitude towards abortion, current abortion provision or help with abortion provision using mifepristone-misoprostol, mid-level providers on staff at the health facility, and type of health facility where the provider worked. Both models controlled for provider sex (male/female), age (years) and health facility location (urban/rural).

Findings

Characteristics of providers

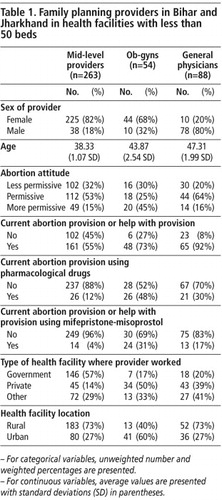

The majority of family planning providers in Bihar and Jharkhand held “permissive” or “more permissive” attitudes towards abortion. Overall, 15% of mid-level providers, 45% of obstetrician-gynaecologists and 16% of general physicians had a “more permissive” attitude (Table 1). The majority in each group reported providing or helping to provide abortion services: 55% of mid-level providers, 73% of obstetrician-gynaecologists and 92% of general physicians. Twelve per cent of mid-level providers reported providing any pharmacological drugs for abortions. Forty-eight per cent of all obstetrician-gynaecologists offered pharmacological drugs for abortion and 31% reported using mifepristone-misoprostol. Thirty per cent of general physicians reported providing any pharmacological drugs, with 17% reporting providing mifepristone-misoprostol.

Most mid-level providers were based at government health facilities, whereas the majority of obstetrician-gynaecologists and general physicians worked at non-public facilities. Most mid-level providers and general physicians worked at rural health facilities, whereas the majority of obstetrician-gynaecologists practised in urban areas.

Mid-level provider interest in early medical abortion training

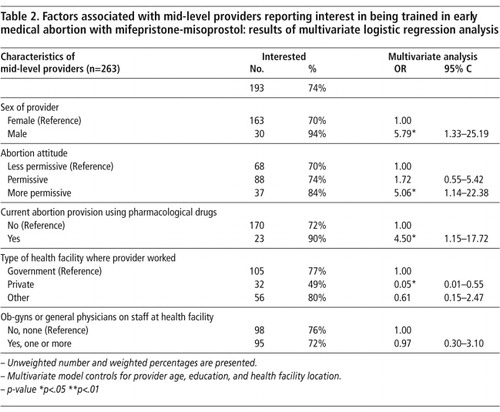

Overall, 74% of mid-level providers showed interest in training for early medical abortion (Table 2). A significantly higher proportion of men (94%) compared to women (70%) expressed interest. Ninety per cent of mid-level providers who had provided pharmacological drugs for abortion showed interest in attending training. Almost half of those working in private health facilities and over three-quarters in government facilities were interested. Bivariate analysis showed that interest was not associated with attitude towards abortion, current abortion provision using any pharmacological drugs, type of health facility where the provider worked, or presence of obstetrician-gynaecologists or general physicians at the health facility. Mid-level provider sex was the only variable that was statistically significantly associated at the bivariate level with interest in training for early medical abortion provision.

In the multivariate logistic regression model, sex of provider, attitude towards abortion, current abortion provision using any pharmacological drugs, and type of health facility where the provider worked were associated with mid-level provider interest in attending early medical abortion training (controlling for provider age, education and health facility location). Male mid-level providers were much more likely to be interested than females (OR 5.79, p<.05). Mid-level providers reporting more permissive abortion attitudes were significantly more likely to be interested in training than those with less permissive attitudes (OR 5.06, p<.05). Current providers of abortion using any pharmacological drugs were also more likely to be interested compared to those not providing such drugs (OR 4.50, p<.05). Furthermore, those working at private health facilities were much less likely to be interested than those at government facilities (OR .05, p<.05).

Attitudes of obstetrician-gynaecologists

Overall, 34% of obstetrician-gynaecologists were supportive of non-physicians' participation in early medical abortion provision (Table 3). However, bivariate analysis showed that 95% of those with more permissive attitudes to abortion were not supportive, and only 11% of those working with mid-level providers were supportive. In contrast, 82% of obstetrician-gynaecologists who did not work with mid-level providers were supportive of non-physicians receiving training.

In multivariate analysis, obstetrician-gynaecologists with more permissive abortion attitudes (OR 0.01, p<.05) and those who provided abortions using mifepristone-misoprostol (OR 0.03, p<.05) at the time of the survey were substantially less likely to be supportive of non-physician provision of early medical abortion (after controlling for provider sex, age and health facility location).

Attitudes of general physicians

Fifty-eight per cent of general physicians supported non-physicians being trained in early medical abortion provision (Table 3). Bivariate analyses found significant differences in extent of support depending on the type of health facility where they worked. A slightly lower percentage of general physicians working at private facilities were supportive compared to those in government facilities.

Multivariate analyses (after controlling for provider sex, age and health facility location) found that general physicians working for private (OR 0.02, p<.01) or other types of health facilities (OR 0.04, p<.05) were substantially less likely to support non-physician training compared to those at government facilities.

Discussion

This study shows that the majority of mid-level providers interviewed in Bihar and Jharkhand were interested in being trained to provide early medical abortion in 2004. Since then, medical abortion drugs have become more commonly available throughout India, and it is highly likely that interest in providing them has also risen among providers.

The fact that male mid-level providers were more likely to be interested in pursuing early medical abortion training compared to their female counterparts was counter to expectations. No published studies to our knowledge have explored this difference. However, in this region men are traditionally the main income generators and perhaps they were quicker to perceive the potential to increase their income by learning new skills. How women needing an abortion would feel about male providers of medical abortion is not known. Women in India have reported not seeking out health care if a female provider is not available, due to fear and embarrassment of being examined by a male health care provider.Citation40–42 However, receiving medical abortion drugs from a man may not concern women as much, as it is a non-invasive process.

Our findings as regards permissive attitudes towards abortion and interest in training were consistent with findings from research in the United States among nurse practitioners, physician assistants and certified nurse-midwives, whose favourable attitudes towards abortion were associated with their desiring medical abortion training.Citation31 Not only do a high number of mid-level providers in Bihar and Jharkhand want to participate in early medical abortion training, but those already providing medical abortion were more likely to want to obtain the proper skills to do so.

Mid-level providers working at private, for-profit facilities were less likely to be interested in training compared to those working at government facilities. This may be because those at private, for-profit facilities were likely to have clearly delineated roles and responsibilities with fewer opportunities for advancement. We had expected that providers working at facilities with no physicians on staff might be more likely to want training, in order to satisfy the needs of abortion seekers in their communities. This did not prove to be the case, however.

Overall, physicians in Bihar and Jharkhand were fairly supportive of non-physicians being trained to provide early medical abortion services. These results come from small samples; hence, the standard errors are large and confidence intervals wide. Nevertheless, our findings underscore important differences between obstetrician-gynaecologists and general physicians in this region. General physicians were much more supportive of non-physician training for early medical abortion than obstetrician-gynaecologists. A higher percentage of general physicians also reported providing or helping to provide abortion services compared to obstetrician-gynaecologists, which was unexpected. These differences may be related to the fact that the majority of obstetrician-gynaecologists practised in urban areas and general physicians largely worked for rural facilities. The majority of the population in Bihar and Jharkhand is rural where there are few obstetrician-gynaecologists and a high demand for abortion services. In these circumstances, general physicians may be more likely to see the consequences of lack of access to safe abortion services.

On the other hand, obstetrician-gynaecologists who were providing medical abortion may have had concerns about the capabilities of less trained clinicians to prescribe medication and manage patients appropriately. Alternatively, their lack of support may have been due to simple income-related reasons. The more providers there are, the more competition there is and potentially the less income. Obstetrician-gynaecologists may also feel territorial, as abortion is a service they have traditionally provided. The fact that the general physicians working in private health facilities were less likely to be supportive of non-physician provision of medical abortion than those in government facilities may be based on similar economic reasons.

This study has three important limitations. First, clinics with more than 50 beds were excluded in the sampling design, so the findings may not be generalizable to all health care providers and facilities in the two states. Secondly, we were not able to conduct in-depth interviews with respondents to learn the reasons for their views. This limited our interpretation of the findings, though some explanations are supported by other research. A final limitation is the cross-sectional nature of this study. Cross-sectional studies can investigate associations between various factors and outcomes of interest. However, because they are carried out at one point in time and can give no indication of the sequence of events, it is impossible to infer causality.

Conclusion

This study has identified an enabling environment for expanding authorization and training for mid-level providers to offer early medical abortion. A majority of mid-level providers surveyed expressed an interest in receiving training to provide medical abortion services. Additionally, physicians, particularly those in the public sector, supported such training. Policymakers and other stakeholders should take advantage of this supportive environment by increasing the pool of cadres who can legally provide safe abortion services. This is particularly relevant for Bihar and Jharkhand, as the majority of the population in both states are based in rural areas, where non-physician providers are the front-line health workers.

While the majority of general physicians surveyed were supportive of mid-level providers offering medical abortion, the majority of obstetrician-gynaecologists were not. Those who support this form of task shifting should seek to work with physicians who have reservations about it. Over time, and with experience of mid-level providers' skills and capabilities, these reservations may be reduced, as has occurred in the United States in the past two decades.Citation43 As regards the substantial minority of obstetrician-gynaecologists and general physicians who have less permissive attitudes toward abortion, values clarification activities may be helpful, and exposure to the public health justification for reducing maternal mortality from unsafe abortion. Possibly the best strategy for achieving safe abortion is to permit trained mid-level providers to offer abortion services, especially in rural communities. This study suggests that the majority of providers in Bihar and Jharkhand support this idea and would avail themselves of training and service delivery opportunities if they were offered.

References

- R Chhabra, S Nuna. Abortion in India: An Overview. 1993; Veerendra Printers: New Delhi.

- S Mundle, B Elul, A Anand. Increasing access to safe abortion services in rural India: experiences with medical abortion in a primary health center. Contraception. 76(1): 2007; 66–70.

- B Ganatra, HB Johnston. Reducing abortion-related mortality in South Asia: a review of constraints and a road map for change. Journal of American Medical Women's Association. 57(3): 2002; 159–164.

- SS Hirve. Abortion law, policy and services in India: a critical review. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24 Suppl): 2004; 114–121.

- International Institute for Population Sciences. National family health survey-2 India, 1998–99. 2000; IIPS/Mumbai Measure DHS+/ORC Macro: Mumbai/Calverton MD.

- DH Peters. Better Health Systems for India's Poor: Findings, Analysis, and Options. 2002; World Bank Publications: Washington DC.

- HB Johnston, R Ved, N Lyall. Where do rural women obtain postabortion care? The case of Uttar Pradesh, India. International Family Planning Perspectives. 29(4): 2003; 182–187.

- ME Khan, S Barge, N Kumar. Abortion in India : current situation and future challenges. S Pachauri. Implementing a reproductive health agenda in India: the beginning. 1999; Population Council South & East Asia Regional Office: New Delhi, 507–529.

- Government of India. The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act; 1971.

- UNICEF. UNICEF India - Statistics. At: <www.unicef.org/infobycountry/india_statistics.html. >. Accessed 7 December 2008.

- K Coyaji. Early medical abortion in India: three studies and their implications for abortion services. Journal of American Medical Women's Association. 55(3 Suppl): 2000; 191–194.

- Government of India. Family Welfare Programme in India Yearbook 2001. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2003.

- M Sood, Y Juneja, U Goyal. Maternal mortality and morbidity associated with clandestine abortions. Journal of Indian Medical Association. 93(2): 1995; 77–79.

- Registrar General India. Maternal Mortality in India: 1997–2003: Trends, Causes and Risk Factors. 2006; Registrar General India: New Delhi.

- World Health Organization. Safe Abortion: technical and policy guidance for health systems. 2003; WHO: Geneva.

- Ipas. Deciding women's lives are worth saving: Expanding the role of mid-level providers in safe abortion care. 2002; Ipas: Chapel Hill NC.

- DL Billings, TL Baird, V Ankrah. Training midwives to improve postabortion care in Ghana : major findings and recommendations from an operations research project. 1999; Ipas: Chapel Hill, NC.

- L Hessini. Global progress in abortion advocacy and policy: an assessment of the decade since ICPD. Reproductive Health Matters. 13(25): 2005; 88–100.

- B Elul, C Ellertson, B Winikoff. Side effects of mifepristone-misoprostol abortion versus surgical abortion. Data from a trial in China, Cuba, and India. Contraception. 59(2): 1999; 107–114.

- B Winikoff, I Sivin, KJ Coyaji. Safety, efficacy, and acceptability of medical abortion in China, Cuba, and India: a comparative trial of mifepristone-misoprostol versus surgical abortion. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 176(2): 1997; 431–437.

- JT Henderson, AC Hwang, CC Harper. Safety of mifepristone abortions in clinical use. Contraception. 72(3): 2005; 175–178.

- H Hamoda, PW Ashok, GM Flett. Medical abortion at 9–13 weeks' gestation: a review of 1076 consecutive cases. Contraception. 71(5): 2005; 327–332.

- B Elul, N Sheriar, A Anand. Are obstetrician-gynaecologists in India aware of and providing medical abortion?. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of India. 56(4): 2006; 340–345.

- B Kruse. Advanced practice clinicians and medical abortion: increasing access to care. Journal of American Medical Women's Association. 55(3 Suppl): 2000; 167–168.

- Harvey SM, Sherman SA, Bird ST, et al. Understanding medical abortion: Policy, politics and women's health. Policy Matters Paper 3. Eugene: University of Oregon. Center for the Study of Women in Society; 2002.

- L Ramachandar, PJ Pelto. Abortion providers and safety of abortion: a community-based study in a rural district of Tamil Nadu, India. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24 Suppl): 2004; 138–146.

- R Duggal. The political economy of abortion in India: cost and expenditure patterns. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24 Suppl): 2004; 130–137.

- B Elul, H Bracken, S Verma. Unwanted pregnancy and induced abortion in Rajasthan, India: A qualitative exploration. 2004; Population Council: New Delhi.

- Hord CE, Baird TL, Billings DL. Advancing the Role of Mid-level Providers in Abortion and Postaboprtion Care: A Global Review and Key Future Actions: Ipas; 1999.

- LJ Beckman, SM Harvey, SJ Satre. The delivery of medical abortion services: the views of experienced providers. Women's Health Issues. 12(2): 2002; 103–112.

- AC Hwang, A Koyama, D Taylor. Advanced practice clinicians' interest in providing medical abortion: results of a California survey. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 37(2): 2005; 92–97.

- L Ramachandar, PJ Pelto. Medical abortion in rural Tamil Nadu, South India: a quiet transformation. Reproductive Health Matters. 13(26): 2005; 54–64.

- B Ganatra, V Manning, SP Pallipamulla. Medical Abortion in Bihar and Jharkhand: A Study of Provders, Chemists, Women and Men. 2005; Ipas India: New Delhi.

- AA Creanga, P Roy, AO Tsui. Characteristics of abortion service providers in two northern Indian states. Contraception. 78(6): 2008; 500–506.

- International Institute for Population Sciences/ORC Macro. National family health survey-3 India, 2005–06, Bihar. 2007; IIPS: Mumbai.

- International Institute for Population Sciences/ORC Macro. National family health survey-3 India, 2005–06, Jharkhand. 2007; IIPS: Mumbai.

- International Institute for Population Sciences/ORC Macro. National family health survey-3 India, 2005–06. 2007; IIPS: Mumbai.

- Carolina Population Center. Alternative Business Models for Family Planning. At: <www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/abm. >. Accessed 26 September 2008.

- R Stephenson, AO Tsui, S Sulzbach. Franchising reproductive health services. Health Services Research. 39(6): 2004; 2053–2080.

- L Bandyopadhyay. Lymphatic filariasis and the women of India. Social Science & Medicine. 42(10): 1996; 1401–1410.

- G Rangaiyan, S Sureender. Women's perceptions of gynaecological morbidity in South India: Causes and remedies in a cultural context. Journal of Family Welfare. 46(1): 2000; 31–38.

- BJ Helen, S Prasad, K Abraham. Reproductive Tract Infections Among Young Married Women in Tamil Nadu, India. International Family Planning Perspectives. 31(2): 2005; 73–82.

- M Berer. Provision of abortion by mid-level providers: international policy, practice and perspectives. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 87(1): 2009; 58–63.