Abstract

Although the HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men (MSM) in South Africa preceded the onset of the generalised HIV epidemic by several years, current policies and programmes focus on heterosexual transmission and mother-to-child transmission. We used an adaptation of the UNAIDS Country Harmonised Alignment Tool (CHAT) to assess whether existing HIV policies and programmes in South Africa address the needs of MSM. This covered mapping of key risk factors and epidemiology of HIV among MSM; participation of MSM in the HIV response; and an enabling environment for service provision, funding and human resources. We found that current policies and programmes are unresponsive to the needs of MSM and that epidemiologic information is lacking, in spite of policy on MSM in the National Strategic Plan. We recommend that government initiate sentinel surveillance to determine HIV prevalence among MSM, social science research on the contexts of HIV transmission among MSM, and appropriate HIV prevention and care strategies. MSM should be closely involved in the design of policies and programmes. Supportive programme development should include dedicated financial and human resources, appropriate guidelines, and improved access to and coverage of HIV prevention, treatment and care services for MSM

Résumé

Même si en Afrique du Sud, l'épidémie de VIH chez les hommes ayant des rapports sexuels avec des hommes (HSH) a précédé de plusieurs années le début de l'épidémie généralisée, les politiques et programmes actuels sont focalisés sur la transmission hétérosexuelle et mère-enfant. Nous avons adapté l'outil d'harmonisation et d'alignement national (CHAT) de l'ONUSIDA pour évaluer si les politiques et programmes sud-africains répondent aux besoins des HSH. Nous avons pour cela examiné les principaux facteurs de risque et l'épidémiologie du VIH chez les HSH ; la participation des HSH à la riposte au VIH ; et l'environnement propice pour la prestation des services, le financement et les ressources humaines. Nous avons découvert que les politiques et programmes ne satisfont pas les besoins des HSH et que l'information épidémiologique fait défaut, en dépit de la politique sur les HSH dans le Plan stratégique national. Nous recommandons au Gouvernement commence une surveillance sentinelle afin d'évaluer la prévalence du VIH chez les HSH, une recherche en sciences sociales sur les contextes de la transmission du VIH chez les HSH et des stratégies adaptées de prévention et de soins du VIH. Les HSH doivent être étroitement associés à la conception des politiques et des programmes. La définition de programmes positifs devrait inclure des ressources humaines et financières dédiées, des directives appropriées et une couverture étendue de la prévention, du traitement et des soins, ainsi qu'un accès élargi des HSH à ces services.

Resumen

Aunque en Sudáfrica la epidemia del VIH entre hombres que tienen relaciones sexuales con hombres (HSH) precedió por varios años al inicio de la epidemia generalizada del VIH, las políticas y los programas actuales se centran en la transmisión heterosexual y la transmisión materno-infantil. Usamos una adaptación del Mecanismo Nacional de Armonización y Concordancia (CHAT), creado por ONUSIDA, con el fin de determinar si las políticas y los programas de VIH en Sudáfrica satisfacen las necesidades de los HSH. Se abarcó el mapeo de los factores de riesgo clave y la epidemiología del VIH entre HSH; la participación de los HSH en respuesta al VIH; y un ambiente propicio para la prestación de servicios, financiamiento y recursos humanos. Encontramos que las políticas y los programas vigentes no son receptivos a las necesidades de los HSH y que falta información epidemiológica, pese a la política de HSH del Plan Estratégico Nacional. Recomendamos que el gobierno inicie vigilancia centinela para determinar la prevalencia de VIH entre HSH, investigación en ciencias sociales sobre el contexto de la transmisión del VIH entre HSH, y estrategias adecuadas para la prevención y el tratamiento del VIH. Los HSH deben participar estrechamente en la formulación de políticas y programas. El desarrollo de programas de apoyo debe incluir recursos financieros y humanos dedicados, directrices apropiadas y mejor acceso a los servicios de prevención, tratamiento y atención del VIH entre HSH, así como mejor cobertura de estos.

South Africa is experiencing a generalised HIV epidemic, with approximately 5.5 million people living with HIV.Citation1 Recent evidence suggests that even in countries with generalised HIV epidemics, the risk of acquiring HIV infection is considerably higher among men who have sex with men (MSM) than in the general population.Citation2–4 The term MSM describes a social and behavioural construct and refers to any men who have sex with other men, irrespective of whether or not they also have sex with women.Citation5 MSM include men of various sexual identities, including men who do not self-identify as homosexual or gay.Citation5

In the 1980s, early in the HIV epidemic in South Africa, most cases of HIV and AIDS occurred either among gay men or people such as haemophiliacs who had received infected blood products.Citation6 The emergence of a generalised HIV epidemic eclipsed the epidemic among MSM, with a shift in focus of HIV surveillance and intervention programmes towards heterosexual transmission and mother-to-child transmission.Citation7

Given the disproportionate impact that the HIV pandemic has had on MSM globally, their needs should form an integral part of the national HIV and AIDS response. To date, however, UNGASS indicators pertaining to MSM have not been included in South African country reports submitted to UNAIDS.Citation8 The South African HIV & AIDS and STI National Strategic Plan 2007-2011 acknowledges that there is currently very little known about the epidemic amongst MSM in the country and that MSM have also not been considered in national HIV and AIDS interventions.Citation7 But it does advocate that as one of the “higher risk populations” MSM should be included in the roll-out of increased prevention programmes including voluntary counselling and testing, provision of condoms and STI symptom recognition.Citation7

In view of the knowledge and programme gaps identified in the National Strategic Plan, we set out to assess the extent to which current HIV policies and programmes meet the needs of MSM in South Africa, and to make recommendations for policy and programme implementation.

Conceptual framework for analysis and methodology

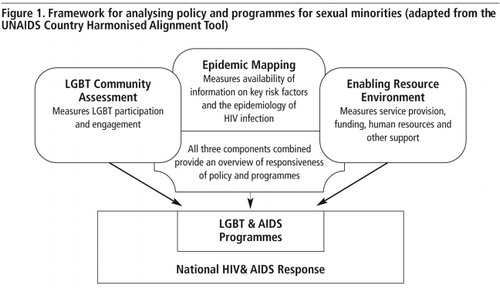

We adapted the conceptual framework of the Country Harmonised Alignment Tool of UNAIDSCitation9 to assess the extent to which HIV policies and programmes in South Africa meet the needs of MSM (). This framework was developed by UNAIDS and the World Bank to assist national AIDS coordinating authorities to assess both the participation and engagement of country-based partners in the national HIV response and to assist international agencies with harmonisation and alignment of their responses. The adapted framework has three dimensions of analysis: epidemic mapping, which measures availability of information on key risk factors and the epidemiology of HIV infection among MSM; community assessment, which measures participation and engagement of MSM in the HIV response; and the presence of an enabling environment, which measures service provision, funding, human resources, and other forms of support.

Our assessment is based primarily on a literature review. We searched for published abstracts and manuscripts related to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, MSM and HIV in South Africa. We conducted initial searches using PubMed. The search included an iterative process using various combinations of the following key words: HIV; MSM; MSM epidemiology; MSM sexual behaviour; LGBTI; MSM risk factors; HIV prevention strategies; HIV policies; stigma; discrimination and health programmes. We also obtained grey material from LGBTI organisations in South Africa and analysed the South African National Strategic Plan on HIV and AIDS and STIs. However, the literature review was neither systematic nor exhaustive.

The section on the enabling environment also draws on preliminary findings of primary research conducted as part of the Johannesburg/eThekwini Men's Study (JEMS), which focused on HIV among MSM in two South African cities. JEMS was a pilot study as a step towards initiating national HIV surveillance among MSM, as part of the implementation of the National Strategic Plan. The aims of the study were to review existing information on HIV among MSM in SA; to assess programmes and services currently available to MSM; to determine HIV prevalence and risk behaviours among MSM in Johannesburg and Durban; and to make preliminary recommendations to policy-makers. Key informant interviews were conducted with 32 people. These included LGBTI advocates; people working for LGBTI organisations; government HIV policy-makers and programme managers; and researchers and other experts on MSM and HIV in South Africa.

In this paper, we focus on MSM because surveillance of HIV among MSM, and HIV programmes for MSM are both identified in the National Strategic Plan as priority gaps to be addressed; and because more information is available on MSM, compared to other sexual minorities. The choice to limit our analysis to MSM should not be taken to imply that other sexual minorities do not merit a separate analysis.

Mapping of the epidemic among MSM and key risk factors

There is evidence of emerging epidemics of HIV infection among MSM in many developing countries.Citation2–4,10 UNAIDS advocates that sub-epidemics among MSM should be regarded as linked to the epidemic in the general population.Citation11 However, the prevalence of HIV infection among MSM in developing countries is sometimes not indicative of the overall HIV prevalence in the general population.Citation12–15 A recent systematic review of HIV among MSM in low- and middle-income countries found that the prevalence of HIV among MSM exceeded that in the general population in 37 of 38 countries for which information was available, and that in many countries the prevalence of HIV among MSM was several-fold higher than in the general population.Citation16

In Africa, the first HIV sero-prevalence survey among MSM was conducted in Senegal in 2005.Citation13 The study found an HIV prevalence of 21.5% among MSM, compared to 0.2% among adult males overall.Citation13 Similarly, a survey of MSM in Kenya between 2005-2007 found an HIV prevalence of over 40%, compared to 6.1% among Kenyan adults aged 15-49 years.Citation17 It has been hypothesised that HIV prevalence among MSM in South Africa may also exceed that in the general populationCitation18 but evidence is lacking.

Information on the incidence and prevalence of HIV among MSM in South Africa, and risk behaviour and prevention strategies used by MSM, is extremely limited.Citation19 Most of the early cases of AIDS diagnosed in South Africa were among white MSM who had travelled internationally, and who had a history of sexual contact with men from other countries.Citation19–23

The proportion of men in South Africa who engage in sex with other men is unknown. Furthermore, HIV infection and AIDS remain highly stigmatised, adding to the challenge of characterising the HIV epidemic among MSM.Citation24 In South Africa, ongoing surveillance of the HIV epidemic consists of annual surveys of pregnant women attending antenatal clinicsCitation25 and national household surveys every three years.Citation26 Antenatal surveys as a means of estimating national HIV prevalence can be misleading, and recent estimates of HIV prevalence based on antenatal surveys alone have been questioned.Citation27 National household surveys conducted by the Human Sciences Research Council in 2002 and 2005 showed that HIV prevalence was high among both men and women in the general population of South Africa, and peaked at an older age among men than among women.Citation26Citation28 Neither these two surveys nor the 2008 national household survey have included any questions about same-sex sexual behaviour (attributed in part to concerns about privacy),Citation26Citation28 nor information on the HIV epidemic among MSM either.

Information from other studies is also extremely limited. A 2004-05 study among 17 000 South African public school teachers to examine the impact of HIV/AIDS on the public education sector found that HIV prevalence among male teachers who reported having sex with men (14.4%) was only slightly higher than that found among male teachers who reported having sex with women only (12.8%); the difference was not statistically significant.Citation29 The lack of accurate information has been highlighted in key events and meetings in recent years. In 2006, when the South African National Blood Transfusion Services announced that they would not accept blood from men who had engaged in oral or anal sex in the previous five years, regardless of whether they used protection,Citation30 they argued that:

“Men who have sex with another man are universally barred as blood donors because this is recognised as high risk behaviour for HIV infection and transmission… [However,] SANBS recognises that there are no local data to support the view that in South Africa, as elsewhere, men who have sex with men pose a significant risk to the blood supply.”Citation31

In 2007, at three meetings – a same-sex sexuality conference,Citation32 a high-level meeting with the deputy Minister of Health on the National Strategic Plan's research priorities,Citation33 and the third South African AIDS conferenceCitation34 – the lack of information on MSM and the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) communities was emphasised and epidemiological and social science research called for. Two years down the line, there has been little progress. Many factors contribute to this continuing knowledge gap, including societal and community denial, stigma, discrimination and human rights abuses.Citation24,35,36 The lack of information also reflects the lack of stewardship on the part of the government. As was pointed out at the international AIDS conference in Mexico in 2008:

“The best way of denying this reality is by not doing any research at all on this population [MSM] or simply by not believing in scientific evidence.”Citation37

Participation and engagement of MSM in the national response to HIV

Community involvement is widely recognised as key to the AIDS response and to successful implementation of policies and programmes.Citation5 In the 1980s, gay activists were among the first to draw attention to the HIV epidemic in South Africa, to mobilise support for people living with HIV and to introduce HIV prevention programmes.

“I [have been] an [HIV] activist since 1994, I worked with a programme that trained the LGBT sector in Soweto and I learned a lot about HIV. We approached government, but they are not really ready.” (Key informant 5, LGBT activist, 2008)

In recent years, the Joint Working Group, a national network of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) organisations,Citation38 has commissioned a number of studies in an attempt to address the needs of its constituency. Gay activists were also instrumental in the 2006 South African National Blood Transfusion Services policy review and revised screening tool for blood donors.Citation39

The South African National Strategic Plan for 2007-2011Citation7 was the first to mention the needs and involvement in HIV policies and programmes of people in same-sex relationships. The consultative process in drawing it up has been widely considered a major success. It brought together all health stakeholders in the public and private sectors, as well as members of civil society, to tackle the epidemic, including the LGBTI sector.Citation40 However, this only happened after extensive stakeholder critique, lobbying and advocacy in the six months after the first draft of the document was released. A two-day consultative meeting in March 2007 provided stakeholders with an opportunity to make further inputs to the plan and the final version, jointly drafted by civil society representatives and government, was released at the launch of the South African National AIDS Council in April 2007.

As elsewhere, the LGBTI community will need to continue its efforts to lobby for involvement in the design, implementation and evaluation of policies and programmes directed at its constituency. However, if social movements and community participation are to fulfil their potential, then national governments must create and maintain the conditions necessary for genuine participation.

Enabling environment for service provision, funding and human resources

Our analysis also asked whether there is an enabling environment for HIV and AIDS service provision, funding, human resources and other support to MSM in South Africa. South Africa's Constitution, with its highly progressive legal framework, states that:

“The state may not unfairly discriminate directly or indirectly against anyone on one or more grounds, including race, gender, sex, pregnancy, marital status, ethnic or social origin, colour, or sexual orientation.”Citation41

The Constitution also makes provision for the progressive realisation of rights within available resources. South Africa is the only African country where discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is outlawed and where same-sex relationships are formally recognised in law. While these progressive legal frameworks are a critical underpinning of policy development, experience has shown that it has been insufficient to ensure access to resources and services.

“Lesbian and gay people in South Africa remain on the fringes and margins of society. In various mainstream programmes, there is no mention of sexual minorities as a vulnerable group… The state has, thus far, not attempted to address HIV prevention that encompasses the diversity of sexual behaviour present in South Africa.”Citation36

Despite a challenge in 2005 from LGBT organisations at the launch of the state-run HIV prevention campaign known as Khomanani (We care), the campaign proceeded with no messages directed at the LGBTI community.Citation36 At the 3rd South African AIDS Conference in June 2007, delegates made a commitment to make counselling and testing available and accessible to vulnerable groups, including men who have sex with men.Citation34

Meanwhile, LGBTI organisations remain the main providers of services catering specifically for their own constituencies. In a May 2007 submission to the South African Human Rights Commission on access to health care, OUT LGBT Well-being, a Gauteng community-based organisation, submitted that targeted health care services for LGBT people are provided primarily by LGBT organisations, who depend on foreign donors for funding. The organisation argued for accessible and inclusive public health care services and programmes in a safe, non-discriminatory environment.Citation42

But health services remain largely unresponsive,Citation43 and no dedicated funding has been allocated by government to meet the targets outlined in the National Strategic Plan. Information collected by LGBTI organisations suggests that health care practitioners tend to assume heterosexuality, and that some MSM have delayed seeking treatment for conditions such as haemorrhoids, rectal bleeding and genital infections because of fear that their sexual orientation would be discovered and fear of discrimination on the grounds of their sexual orientation.Citation43

Both men and women in same-sex relationships often face stigma and discrimination when accessing health care services in South Africa. A study in one township found that MSM experienced homophobic verbal harassment from health care workers and had to seek out clinics where health workers respected their privacy and their sexuality.Citation44 Due to the stigma experienced by MSM and other LBGT populations, non-conventional channels are often used to obtain health care services. Key informants in the Johannesburg/eThekwini Men's Study bore out these findings.

“Health care providers don't know how to deal with MSM. One person was refused treatment, because the nurse said: ‘How dare you have sex with another man?’ (Key informant 16, NGO focusing on the needs of men, 2008)

“It is better for well-resourced people because you avoid public health services, [but] even in the private sector, you [have to] choose which doctor to go to.” (Key informant 1, LGBT activist living with HIV, 2008)

“There are hetero-normative questions asked regarding HIV, pregnancy. The kinds of questions that are asked and the assumptions made: there is either the fear of offending people or simply not thinking about a different set of questions.” (Key informant 2, HIV expert, 2008)

One senior level provincial health official displayed remarkable ignorance when interviewed about LGBTI challenges with service access:

“If they behave normally, then there is no barrier to services. They still have the same reproductive organs. They must just come to health services, and may need more privacy. They must be treated according to the protocol.” (Key informant 8, government official, 2008)

Recommendations

In South Africa, the HIV epidemic has been highly politicised.Citation45 This is exacerbated by its close association with sex, its labelling as a gay disease, societal prejudices, stigma and discrimination. Decisive government response has been absent in the last two years, and there is neither an implementation plan nor resources allocated to address surveillance or programme gaps. Policy analysts have pointed out that the context, politics, ideology, processes and actors are important factors to take into account in translating policy or research into practice.Citation46Citation47 Hence, we recommend that policy research be done to analyse the political determinants of HIV programme implementation and reasons for leadership inaction to address the prejudice and stigma directed at most-at-risk populations. Policy research is also important to understand how priority setting and resource allocation decisions are made, and the drivers and constraints to change.

• Research to improve understanding of the epidemic

Research in other countries has shown that HIV is widespread among MSM and that without active surveillance and appropriate interventions, the epidemic may flourish, though hidden from view. In South Africa, key areas needing attention are national surveillance and funding of HIV prevalence and behavioural risks among MSM. We believe that such surveillance is a national government responsibility and that the infrastructure exists to carry it out. Consensus about the best methods to use for ongoing surveillance of HIV among MSM needs to be developed, and a mechanism found for coordinating current localised surveillance initiatives.

Both qualitative and quantitative research is needed on factors that place MSM at risk, HIV prevention interventions, and interventions to address stigma towards LGBTI people and people living with HIV. Research should also cover the social contexts of HIV transmission among MSM, HIV prevention strategies among MSM, behavioural and risk-reduction interventions that could be scaled-up, and HIV prevention and care needs.Citation48 Furthermore, research should provide insights into the health service-related barriers to care, attitudes of health professionals and the resources and training required to address these.

Country-level investment in the generation of evidence is an important element of an effective response to HIV among MSM, as shown by the example of Australia.Citation49 Similarly, Senegal established sentinel surveillance in 1989 at an early stage of the epidemic, thus providing valuable scientific evidence to inform decisions and policies.Citation46

• Participation and engagement of MSM in the HIV response

Although the National Strategic Plan includes a commitment to the inclusion of MSM in programme and funding priorities, this is largely unchartered terrain for government. Involvement and engagement of the LGBTI sector is critical, given the often overt discrimination that exists, to ensure that policies and programmes protect and respect LGBT people's right to privacy regarding their sexual orientation and that their needs are taken into account in programme design.

Strong and sustained partnership between government, non-governmental organisations, health care practitioners and researchers is critical, as has been shown by Australia's successful response to HIV and its ability to contain the spread of HIV among MSM.Citation50 While partnerships are important, a strong LGBTI movement is also needed to hold government accountable for its stated commitments. LGBTI organisations could learn from the strategies and tactics used by the Treatment Action Campaign in South Africa to bring about successful policy change and implementation, including building alliances among different constituencies; widespread dissemination of scientific evidence in an easy-to-understand format and framing the AIDS struggle within broader political and economic struggles of South Africa.Citation51

• Development of supportive programmes

Government has a critical role in ensuring the provision of sexual and reproductive health services in a supportive and non-discriminatory environment for vulnerable populations, including sexual minorities. With government support, the targets in the National Strategic Plan could be met, even with current financial resource constraints. A public sector infrastructure is already in place. Change in mindset to acknowledge same-sex behaviour and the revision of HIV and AIDS guidelines and programmes to meet the needs of MSM would go a long way towards addressing services gaps, without incurring extra costs. Public sector health services need to become more responsive. An effective response requires a minimum package of services, which includes at least: targeted and specific information, education and communication; improving availability of condoms and lubricants and distribution to non-health facilities; condom promotion and social marketing; STI diagnosis and treatment and antiretroviral treatment, care and support services and behavioural interventions suitable for the country. Creative strategies are needed to improve access to care, including outreach programmes.

Sensitivity training of health care professionals is essential to overcome ignorance and prejudices about MSM. Appropriate clinical guidelines on the assessment of sexual risk; screening for STIs and HIV, depression, substance abuse and other clinical conditions (e.g. hepatitis) should be developed.Citation52 The guidelines should include routinely asking about sexual orientation in a non-judgmental manner, taking a confidential sexual history, discussing what will be included in the medical record, avoiding labels when talking about sexual practices and sexual and gender identity, and doing examinations in a private and respectful manner.

Lastly, structural issues that increase vulnerability to HIV must be addressed, including stigma, discrimination and homophobia. This aspect is already contained in the National Strategic Plan, but we recommend that greater attention be paid to enforcing a human rights culture in all aspects of HIV management. Annual human rights events should also be used to emphasise the rights of all people, and anti-stigma and anti-discrimination messages should be part of national HIV social marketing campaigns.

South Africa still has some way to go in creating an enabling environment to address HIV among MSM, let alone the wider LGBTI community. Creative strategies are needed to ensure prevention of new infections among the whole population and to turn the tide of the epidemic.

Acknowledgements

This paper arose primarily from a brief talk given by LR at the Same-Sex Sexuality Conference in May 2007, Pretoria, revised for inclusion in the conference proceedings, and a literature review as part of the Johannesburg/ eThekwini Men's Study (JEMS), which is unpublished. It was substantially reworked for publication here. The views in the paper are those of the authors, and do not necessarily represent those of the organisers of the Same-Sex Sexuality Conference or our employers.

References

- UNAIDS. Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. 2008; UNAIDS: Geneva.

- C Beyrer. Hidden yet happening: the epidemics of sexually transmitted infections and HIV among men who have sex with men in developing countries. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 84: 2008; 410–412.

- S Baral, F Sifakis, F Cleghorn. The epidemiology of HIV among MSM in low- and middle-income countries: high rates, limited responses. AmfAR Special Report: MSM, HIV and the Road to Universal Access – How Far have we Come?. August. 2008; AmfAR: New York, 9–12.

- CF Cáceres, K Konda, ER Segura. Epidemiology of male same-sex behaviour and associated sexual health indicators in low- and middle-income countries: 2003–2007 estimates. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 84: 2008; i49–i56.

- UNAIDS. Report on the global AIDS epidemic: a UNAIDS 10th anniversary special edition. 2006; UNAIDS: Geneva, 110.

- J Van Harmelen, R Wood, M Lambrick. An association between HIV-1 subtypes and mode of transmission in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS. 11(1): 1997; 81–87.

- Department of Health. HIV & AIDS and STIs. National Strategic Plan for South Africa, 2007–2011. 2007; Department of Health: Pretoria.

- Ministry of Health of the Republic of South Africa. Progress Report on Declaration of Commitment on HIV and AIDS, Republic of Commitment: Reporting period January 2006-December 2007. 2008; Ministry of Health: Pretoria.

- UNAIDS. Country Harmonisation and Alignment Tool. A tool to address harmonisation and alignment challenges by assessing strengths and effectiveness of partnerships in the national AIDS response, 2007. UNAIDS/07/07.17E/JC1231E (ISBN 978 92 9173 580 8).

- C Beyrer. HIV epidemiology update and transmission factors: risks and risk contexts-16th International AIDS conference epidemiology plenary. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 44: 2007; 981–987.

- UNAIDS. HIV and sex between men: policy brief. 2006; UNAIDS: Geneva.

- P Girault, T Saidel, N Song. HIV, STIs and sexual behaviours among men who have sex with men in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. AIDS Education & Prevention. 16: 2004; 31–44.

- AS Wade, CT Kane, PA Diallo. HIV infection and sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men in Senegal. AIDS. 19: 2005; 2133–2140.

- F Van Griensven, S Thanprasertsuk, R Jommaroeng. Evidence of a previously undocumented epidemic of HIV infection among men who have sex with men in Bangkok, Thailand. AIDS. 19: 2005; 521–526.

- F Van Griensven. Men who have sex with men and their epidemics in Africa. AIDS. 21(10): 2007; 1361–1362.

- S Baral, F Sifakis, F Cleghorn. Elevated risk for HIV infection among men who have sex with men in low- and middle-income countries 2000–2006: a systematic review. PLoS Medicine. 4(12): 2007; e339.

- EJ Sanders, SM Graham, HS Okuku. HIV-1 infection in high risk men who have sex with men in Mombasa, Kenya. AIDS. 21(18): 2007; 2513–2520.

- TGM Sandfort, J Nel, E Rich. HIV testing and self-reported HIV status in South African men who have sex with men: results from a community-based survey. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 84: 2008; 425–429.

- J Van Harmelen, R Wood, M Lambrick. An association between HIV-1 sub-types and mode of transmission in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS. 11: 1997; 81–87.

- R Sher, L dos Santos. Prevalence of HTLV-III antibodies in homosexual men in Johannesburg. South African Medical Journal. 67(13): 1985; 484.

- R Sher. AIDS in Johannesburg. South African Medical Journal. 68(3): 1985; 137–138.

- R Sher. Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) in the RSA. South African Medical Journal Supplement. 1986; 23–26.

- R Sher. HIV infection in South Africa, 1982–1988: a review. South African Medical Journal. 76(7): 1989; 314–318.

- A Cloete, LC Simbayi, SC Kalichman. Stigma and discrimination experiences of HIV positive men who have sex with men in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Care. 20(9): 2008; 1105–1110.

- Department of Health. National HIV and syphilis antenatal sero-prevalence survey in South Africa 2007. 2008; Department of Health: Pretoria.

- O Shisana, T Rehle, LC Simbayi. South African National HIV prevalence, HIV incidence, behaviour and communication survey. 2005; Human Sciences Research Council Press: Cape Town.

- R Dorrington, D Bourne. Has HIV prevalence peaked in South Africa? Can the report on the latest antenatal survey be trusted to answer this question?. South African Medical Journal. 98(10): 2008; 754–755.

- O Shisana, L Simbayi. Nelson Mandela/HSRC Study of HIV/AIDS. South African national HIV prevalence, behavioural risks and mass media household survey, 2002. 2002; Human Sciences Research Council Press: Cape Town.

- O Shisana, K Peltzer, N Zungu-Dirwayi. The Health of Our Educators. A Focus on HIV/AIDS in South African Public Schools. 2005; Human Sciences Research Council Press: Cape Town.

- AIDS data doesn't include gay men-lobbyists. At: <www.iol.co.za/general/news. >. Accessed 13 February 2009.

- A Heyns. Policy and decision making by blood transfusion services in South Africa [Editorial]. South African Medical Journal. 96: 2006; 421–422.

- Reddy V. The erasure of HIV/AIDS in same-sex sexuality research in South Africa: some preliminary perspectives on issues, ideas and prospects. Paper presented at Joint Human Sciences Research Council, Columbia University, Durban Lesbian and Gay Community Health Centre, OUT Same-Sex Sexualities Conference, 9–11 May 2007.

- Deacon H, Sloan J, Mills E, editors. National Strategic Plan research colloquium, Cape Town, 28–29 May 2007, Final Report.

- Building consensus on prevention, treatment and care. Conference Declaration on HIV and AIDS. Durban: 3rd South African AIDS Conference, 5–8 June 2007.

- CA Johnson. Off the map: how HIV/AIDS programming is failing same sex practising people in Africa. 2007; International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission: New York.

- Vilakazi F. There is no mention of sexual minorities: HIV prevention challenges for lesbian and gay people in South Africa. AIDS Legal Network, November 2006.

- Saavedra J, Izazola JA, Beyrer C. Sex between men in the context of HIV. Jonathan Mann Memorial Lecture. Presented at International Conference on AIDS, Mexico City, August 2008.

- Joint Working Group: Access to rights; access to services. At: <www.jwg.org.za. >.

- South Africa lifts ban on blood donations from homosexual men. At: <www.monsterandcritics.com/news/health. >.

- C Kapp. South Africa unveils new 5-year HIV/AIDS plan. Lancet. 369: 2007; 1589–1590.

- Republic of South Africa. Constitution of South Africa, Act No.108 of 1996.

- OUT GLBT Well-being. Health care for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people: issues, implications and recommendations. Submission to South African Human Rights Commission Public Inquiry into the Right to Have Access to Health Care Services, Johannesburg, May 2007.

- Wells H, Polders L. Gay and lesbian people's experience of the health care sector in Gauteng. Joint Working Group Research Initiative, conducted by OUT LGBT Well-being in collaboration with the UNISA Centre for Applied Psychology. Pretoria. (undated).

- T Lane, T Mogale, H Struthers. “They see you as a different thing”: the experiences of men who have sex with men with healthcare workers in South African township communities. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 84: 2008; 430–433.

- H Schneider. On the fault line: the politics of AIDS policy in contemporary South Africa. African Studies. 61(1): 2002; 145–167.

- C Dickinson, K Buse. Understanding the politics of national HIV policies: the roles of institutions, interests and ideas. 2008; HLSP Institute: London.

- L Gilson, D McIntyre. The interface between research and policy: experience from South Africa. Social Science and Medicine. 67: 2008; 748–759.

- Cloete A, Rispel L, Metcalf C. Behind the mask: the need for research on HIV among men who have sex with men in South Africa. Paper presented at Cape Town Pride seminar series, 21 February 2007.

- D Bernard, S Kippax, D Baxter. Effective partnership and adequate investment underpin a successful response. Key factors in dealing with HIV increases. Sexual Health. 5: 2008; 193–201.

- R Griew. Policy and strategic implications of Australia's divergent HIV epidemic among gay men. Sexual Health. 5: 2008; 203–205.

- R Ballard, A Habib, I Valodia. Globalisation, marginalization and contemporary social movements in South Africa. African Affairs. 104(417): 2005; 615–634.

- D Knight. Health care screening for men who have sex with men. American Family Physician. 69: 2004; 2149–2156.