Abstract

Sex work is a criminal offence in San Francisco, USA, and sex work advocates have so far unsuccessfully campaigned for decriminalizing it. Some groups argue that the decriminalization movement does not represent the voices of marginalized sex workers. Using qualitative and quantitative data from the Sex Worker Environmental Assessment Team Study, we investigated the perspectives and experiences of a range of female sex workers regarding the legal status of sex work and the impact of criminal law on their work experiences. Forty women were enrolled in the qualitative phase in 2004 and 247 women in the quantitative phase in 2006-07. Overall, the women in this study seemed to prefer a hybrid of legalization and decriminalization. The majority voiced a preference for removing statutes that criminalize sex work in order to facilitate a social and political environment where they had legal rights and could seek help when they were victims of violence. Advocacy groups need to explore the compromises sex workers are willing to make to ensure safe working conditions and the same legal protections afforded to other workers, and with those who are most marginalized to better understand their immediate needs and how these can be met through decriminalization.

Résumé

La prostitution est un délit pénal à San Francisco (États-Unis) et les militants ont jusqu'à présent fait campagne sans succès pour la décriminaliser. Certains groupes avancent que le mouvement de décriminalisation ne représente pas la voix des professionnels du sexe marginalisés. À l'aide de données qualitatives et quantitatives issues de l'étude réalisée par l'équipe d'évaluation environnementale des professionnelles du sexe, nous avons analysé les perspectives et les expériences de plusieurs prostituées concernant le statut juridique du commerce du sexe et l'impact du droit pénal sur leurs expériences professionnelles. Quarante femmes ont collaboré à la phase qualitative en 2004 et 247 à la phase quantitative en 2006-2007. Dans l'ensemble, les participantes à l'étude semblaient préférer une solution hybride de légalisation et décriminalisation. La majorité d'entre elles souhaitaient une abrogation des textes qui criminalisent la prostitution afin de créer un environnement politique et social qui leur donnerait des droits et où elles pourraient demander de l'aide si elles sont victimes de violences. Les groupes de plaidoyer doivent étudier quels compromis les prostituées sont prêtes à faire pour garantir la sécurité de leurs conditions de travail et les mêmes protections juridiques accordées à d'autres travailleurs. Ils doivent aussi mieux comprendre les besoins immédiats des plus marginalisées et comment y répondre par la décriminalisation.

Resumen

El trabajo sexual es un delito penal en San Francisco, EE.UU., y los defensores del trabajo sexual hasta ahora no han tenido éxito en sus campañas por despenalizarlo. Algunos grupos arguyen que el movimiento de despenalización no representa las voces de las trabajadoras sexuales marginadas. Usando datos cualitativos y cuantitativos del Estudio del Equipo de Evaluación Ambiental de Trabajadoras Sexuales, investigamos las perspectivas y experiencias de una variedad de trabajadoras sexuales concernientes al estado legal del trabajo sexual y el impacto del derecho penal en sus experiencias laborales. Cuarenta mujeres se inscribieron en la fase cualitativa, en 2004, y 247 mujeres en la fase cuantitativa, en 2006-07. En general, las mujeres en este estudio parecieron preferir un híbrido de legalización y despenalización. La mayoría expresó una preferencia por eliminar reglamentos que penalizan el trabajo sexual a fin de facilitar un ambiente social y político en el que tuvieran derechos legales y pudieran buscar ayuda cuando fueran víctimas de violencia. Los grupos de promoción y defensa deben explorar las formas en que las trabajadoras sexuales están dispuestas a transar para garantizar condiciones seguras de trabajo y las mismas protecciones jurídicas otorgadas a los demás trabajadores, y con las personas más marginadas para poder entender mejor sus necesidades inmediatas y cómo atenderlas mediante la despenalización.

Three main legal frameworks address sex work – criminalization, legalization and decriminalization. In San Francisco, and most of the United States, sex work is a criminal offence. This means that the purchase and selling of sexual services, and any associated activities, are criminalized. The various San Francisco statutes associated with sex work include: prostitution, prostitution while HIV-infected, pimping, pandering, soliciting prostitution, loitering with the intent to commit prostitution, conspiracy to commit prostitution, and keeping a house of prostitution. Sex workers may also face drug and public nuisance charges. In many criminalized systems, including San Francisco, the possession of condoms may be used as circumstantial evidence of intent to commit prostitution. (San Francisco Public Defender's Office, Personal communication, 1 September 2009)Citation1 This may lead sex workers to avoid carrying condoms due to fear that they will be used as evidence in a court of law.Citation2 Citation3 Citation4 Citation5

A legalized system permits some, but not necessarily all, types of sex work. In the state of Nevada, counties with a population of 400,000 or fewer may vote on whether to legalize sex work. In these counties, sex work that occurs in a sanctioned brothel is legal while all other forms of sex work are outlawed. Under a legalized framework, those businesses and individuals involved in sex work face regulations and licensing procedures that other businesses do not. In the Nevada brothel system, every sex worker must register with the police department as a brothel worker. They have restricted mobility and stipulated working conditions, and they have mandated weekly testing for gonorrhoea and chlamydia, and monthly testing for HIV and syphilis.Citation6

The third system is decriminalization. In a decriminalized system, the same laws that regulate other businesses regulate sex work. Thus, relevant tax, zoning and employment laws as well as occupational health and safety standards also apply to sex workers and sex work establishments. Unlike legalization, a decriminalized system does not have special laws aimed solely at sex workers or sex work-related activity. This model is found in New Zealand, parts of Australia, the Netherlands and Germany.Citation7

Over the years, many activists in San Francisco have called for the city to decriminalize sex work. Since the 1970s, the organization Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics (COYOTE) has campaigned for decriminalization.Citation8 In 1993, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors called for the establishment of a Task Force on Prostitution. This task force was charged with recommending “social and legal reforms which would best respond to the City's needs while using City resources more efficiently.”Citation9 Their report, issued in 1996, recommended that the City of San Francisco decriminalize prostitution.Citation1 On the November 2008 San Francisco General Election Ballot, Proposition K proposed the decriminalization of sex work. This proposition was endorsed by public health officials, the California Sexually Transmitted Diseases Controller's Association, the San Francisco Democratic Party, as well as sex worker organizations such as the Sex Workers Outreach Project and COYOTE.Citation10 However, with only 42% of San Franciscans voting in favour of it, Proposition K was defeated.Citation11

What should the organizations spearheading decriminalization efforts do next? One critique has been that they have not represented the voices of marginalized sex workers in the community.Citation12 In fact, there are very few studies addressing sex workers' perspectives on the three main legal frameworks. We therefore decided to investigate the perspectives and experiences of a wide range of female sex workers regarding the legal status of sex work and the impact of the law on their working experiences, using data from the Sex Worker Environmental Assessment Team study.

Methods

The Sex Worker Environmental Assessment Team study was a community-based, research partnership between the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), the San Francisco Department of Public Health and the St. James Infirmary (SJI), a peer-based occupational health and safety clinic for sex workers.Citation8 The research received approval from the Committee on Human Research at UCSF.

Former and current sex workers were involved in all aspects of the study — study design, serving as community advisory board members, data collection and analysis, and manuscript preparation. The aim of the analysis reported here was to examine sex workers' experiences with and perspectives on the criminal nature of sex work in San Francisco. For the purposes of the study, we defined sex work as sexual acts (including vaginal, anal, oral and manual stimulation) done for compensation (such as money or other goods of economic value, including but not limited to food, drugs, clothing and housing).

This mixed-method, dual-phase study enrolled 40 female sex workers in an initial qualitative phase and 247 others in a follow-up quantitative phase. The qualitative phase was conducted between April and December 2004 and consisted of semi-structured interviews. To be eligible, women had to be 18 years of age or older and to have engaged in some type of sex work in San Francisco within the past year. The women were recruited through word of mouth as well as targeted recruitment at community-based organizations serving female sex workers. The interviews focused primarily on the social context of their sex work experiences. Each participant was asked a series of open-ended, non-leading questions about their experiences with law enforcement while doing sex work, what they thought their work experiences and life would be like if prostitution was not a criminal offence, and their opinion on the ideal legal framework for sex work. Qualitative data were analyzed in NVIVO version 3.5 (QSR International, Cambridge, MA) using grounded theory.Citation13Citation14 Data collection and analysis were inter-related, iterative processes. Analysis began with open coding and then proceeded to a line-by-line analysis. The findings were used to inform the creation of the instrument for the quantitative phase.

The second phase from October 2006 through November 2007 was a cross-sectional, quantitative study. Eligibility criteria were the same as for the first phase, except women needed to have exchanged sex for compensation within the three months prior to enrolment. The study team and community advisory board identified and recruited an initial six women to participate in the study. The remaining participants were recruited using respondent-driven sampling.Citation15Citation16 Study participants completed a structured, quantitative interview exploring their sexual and drug-using behaviours, mental and physical health, social connectivity and experiences with and perspectives on law enforcement. One portion of the interview queried participants about their attitudes towards criminalization, decriminalization and legalization. In particular, they were asked to respond to various scenarios and legal options. Women were then asked to recruit up to three women in their social network who were also engaged in sex work in the prior three months. We continued to allow waves of recruitment until we reached saturation. Univariate analyses were conducted using SPSS (Chicago, IL).

Findings: qualitative phase

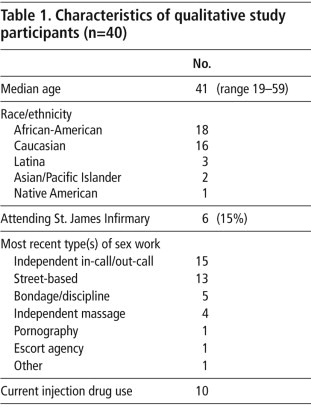

Demographic data are shown in Table 1. The median age was 41 years and the women represented a diversity of races, ethnicity and types of sex work done. Almost half reported a history of injection drug use.

When questioned about the legal framework they preferred for prostitution, the women had a wide range of perspectives on the topic. Ten of them preferred sex work to remain criminalized, eight specifically called for decriminalization, and two preferred legalization. The remaining 20 women did not use the terminology of criminalization, decriminalization or legalization at any point in the interview. The following are examples of the women's perspectives on the various legal approaches to sex work. While only a few of the women's quotes are highlighted, their statements are representative.

Criminalization

The ten women advocating for the continued criminalization of sex work cited an array of reasons, including a preference to avoid government regulation, financial motives and the opportunity to limit drug use while incarcerated.

Several women expressed concern about mandatory health examinations, compulsory documentation, and loss of independence if the current system were to change.

“To tell you the truth, and people say ‘I can't believe that you think this', I like that it is illegal. And one of the reasons that I like that it is illegal is that I am not heavily regulated. And I don't have somebody sticking me with needles, you know, once every couple of months and checking my pussy to see if it's clean. And I can take care of my own health and pay attention to my own health and do what seems right to me, and not be prodded and examined all of the time. Which I've heard from people working in…Nevada. They say that they are just so sick of all of the exams and hoops that they have to jump through, and paperwork that they have to fill out, and that it is very laborious. And I don't have to do any of that.” (Independent massage worker, age 49)

“Everybody be doing it…then it would be too hard to make money.” (Street-based worker, age 41)

“If it wasn't illegal?… The illegality of it keeps the supply and demand balance in a way that I think is in favour of the sex worker, which I really like.” (Independent massage worker, age 49)

“Well, you know, after a while you start looking bad, you are in the same clothes two or three days, the police notice that, you notice that. You are off the hook. There have been times where they have taken me to jail just for drinking in public, and just really saved my behind.” (Street-based worker, age 45)

Decriminalization

The eight women who voiced a desire for a decriminalized system spoke about freedom, safety and support. In particular, they discussed the benefits of having police protection, the ability to build community with other sex workers, and obtaining rights as workers.

“I worked in a legal prostitution setting in Nevada. I did that for a couple of weeks to see what it was like. The amount of controls and the lack of freedom was horrendous. You know, I don't want someone else telling me how to work. And I don't think it is necessary really. Yeah, I think decriminalization gives us the most freedom.” (Independent in-call and out-call worker, age 39)

“I'm actually working on my exit plan, which is being a real estate agent. And one of my fears is that I will not get through the process of getting successful enough in real estate to be able to support myself before I get nailed for something and can't have a licence any more and then I have to start working on a different exit plan.” (Independent massage worker, age 49)

“Police would be there to help instead of saying, ‘Well, you should not have been out here, you would not have been robbed.’ You know, it's like when you are prostituting and something happens to you, the police don't really want to help you, because you are already committing a crime… So it's like why should they help a criminal?” (Street-based worker, age 45)

“The two tensions that I have when I go on a call anonymous, I've never met the person, the two tensions that I feel are, am I going to get hurt, or am I going to get busted? I want the busted part of it out. So that if I do get hurt, I feel confident enough that I can get on the horn and get the authorities to jump on the tail of the person who hurt me.” (Independent out-call worker, age 35)

“I think it would make it easier to negotiate with clients if I could actually say what it is we are talking about. Like if I advertised online and was actually able to say what it is I offer, that would make things so much easier. Or if clients asked me a question and I was able to answer it directly.” (Bondage and discipline worker, age 19)

“It might change the way people perceive or think about sex workers… because that would kind of start to heighten people's awareness about how this moral stigma has affected us.” (Bondage and discipline worker, age 32)

Legalization

Two women specifically expressed a preference for the legalization of sex work. They thought that sex work would be safest under a regulated system. In particular, they could advertise their services clearly without fear of arrest, rely on the police for protection, create safe houses in which to work, and unionize.

“So if we had it in a safe environment, where, say, for example, they could come in here, there are rooms back there, you talk to the client, you screen him. You know, you are saying: ‘So, what is your health history’ and maybe there is a way you can check out a database. You could find out if he had an arrest record for any type of domestic violence… And then that would make it safe for the women.” (Independent out-call worker, age 40)

“[We would] have more police protection if it was legalized too. Health services, mental [health] services, police protection, you know, not having to get thrown out of where you live because of what you do… The same rights as anybody else.” (Independent massage worker, age 49)

Findings: quantitative analysis

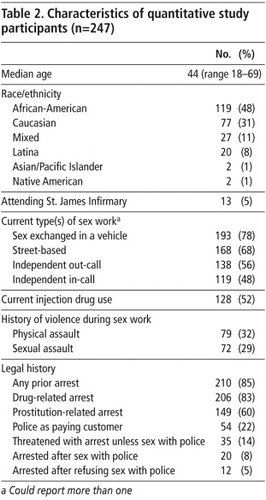

The median age of the women who participated in the quantitative part of the study was 44. As with the qualitative phase, the women engaged in a broad range of sex work activities (Table 2

). Fifty-three per cent were homeless. Thirty-one per cent were recipients of Supplemental Security Income, a federal income supplement designed to help disabled people who have minimal or no income. Another 29% reported receiving General Assistance, a cash grant for indigent adults from the San Francisco government. A high proportion reported drug use, violence in the sex work environment and a history of arrest. Furthermore, 14% described having been threatened with arrest unless they agreed to have sex with a police officer, 8% said they were arrested after having had sex with a police officer, and 5% that they were arrested after refusing to have sex with a police officer. Twenty-two per cent stated they had had police officers as paying customers in the past. In the three months prior to study enrolment, 28% had direct interactions with law enforcement officials. Of these, 40% rated these interactions as very bad or bad.All of the women in this phase were asked about their legal preferences. Table 3

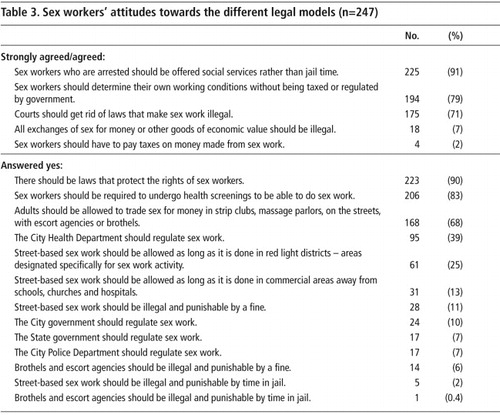

includes the complete list of questions asked on this topic. What follows is a presentation of the quantitative findings from those questions.Criminalization

Very few women in the quantitative phase supported the continued criminalization of sex work. Only 7% felt that all exchanges of sex for money or other goods should be illegal. If sex work were to remain illegal, 92% would want to be offered social services as opposed to incarceration when arrested. Seventy-nine per cent preferred to determine their own working conditions without being taxed or regulated by government.

Decriminalization

The majority of study participants expressed support for certain tenets of a decriminalized model. Seventy-one per cent agreed or strongly agreed that courts should get rid of laws that make sex work illegal. A large portion felt that they should be allowed to trade sex in strip clubs and massage parlors (68%), on the streets (77%), and in escort agencies and brothels (87%). The majority of the women, 82%, preferred street-based sex work to happen in commercial areas and red light districts. Ninety-one per cent wanted laws that protected the rights of sex workers.

Legalization

The legalization of sex work often times results in sex workers and their businesses experiencing heightened forms of regulation that are not witnessed in other businesses. One-third of the women thought that the San Francisco Health Department should regulate sex work, and 84% felt that they should have to undergo health screening to be able to engage in sex work.

Discussion

The sex workers in this study were predominately those who are considered the most marginalized. In the qualitative phase, one-third of the women were street-based sex workers, and 25% were current injection drug users. Over two-thirds of those in the quantitative phase reported current street-based sex work, and over half were current injection drug users. These are the workers who are likely most at risk for physical and sexual assault, as well as arrest. Taking all the women's responses into consideration, their preferences do not fit neatly into any one of the three pre-existing legal frameworks. The majority of sex workers voiced a preference for removing the statutes that criminalize sex work in order to facilitate a social and political environment where they would have legal rights and could seek help when they were victims of violence. They did not want to be arrested for their sex work, yet they also did not want to be regulated by government or pay taxes, sentiments that hold true for many people. Likewise, with over half the women receiving some type of federal or state financial assistance, if they reported sex work income they would likely cease to be eligible for assistance.

While many women voiced their opposition to government oversight, some advocated for elements of regulation that are found in legalized systems, including mandated health screening, and decriminalized models, such as zoning restrictions. It is possible that these responses were influenced by the setting where the interviews were conducted – a sex worker health clinic. As such, they may have felt that health examinations would be done in a community-based, peer-led clinic. The preference that street-based sex work be covered by zoning restrictions may have been informed by the reality that those who work on the street in a criminalized system have very little control over their work situation. If there were specified areas for street prostitution, women might feel safer due to the more controlled nature of the work environment.

An argument frequently used against criminalization is the rampant violence sex workers experience in criminalized settings.Citation1 Citation2 Citation9 Citation18 Citation19 Citation20 Citation21 Citation22 Citation23 Citation24 Police abuse, such as sexual demands in lieu of arrestCitation19Citation23 and excessive use of physical force have been reported, e.g. in Canada and the United States.Citation21Citation25 Most crimes against sex workers go unpunished, as most sex workers do not go to the police when they have been victimized.Citation3 Citation23 Citation26 Few papers address the risk of violence among female sex workers in San Francisco. In a cross-sectional study of 783 adults accessing health care at St. James Infirmary from 1999-2004, we found that 36.3% of the women experienced sex work-related violence, and 7.9% police violence.Citation24 Another study conducted in San Francisco in 1990-91 found that female sex workers, as compared to male and transgender workers, were at higher risk of rape and arrest for prostitution-related offences.Citation27 Hay's article about police abuse of prostitutes in San Francisco acknowledges that the most frequent type of police abuse reported by sex workers, the demand for sex in lieu of arrest, is the hardest to verify. Many of the women in that study reported not filing a complaint when abused by a police officer as they doubted it would result in any positive change. Hay sees police abuse as just another occupational hazard,Citation19 but it is presumably one that could be challenged more readily if prostitution were decriminalized.

Even if sex work were to be decriminalized or legalized, many things might not change. If prostitution codes were removed, there are still other legal codes such as loitering, trespassing, public nuisance and narcotics which could be used to target sex workers. Additionally, given the deep cultural beliefs about sex work, decriminalization or legalization would likely not eliminate the stigma associated with prostitution. A change in the criminal code would also not guarantee access to the health and social services the women want. Incarceration should not be the only way for the women to stop using/drinking or accessing vital services such as health care, drug treatment or housing. Any future work towards decriminalization will need to be coupled with a commitment that the health and social services sex workers want will be available.

The vast majority of women in this study did not want sex work to be a criminal offence, but they did not want to be regulated by government or pay taxes either. This disparate set of preferences cannot co-exist under the framework of decriminalization. Therefore, it is clear that future work by advocacy groups needs to explore with a diversity of sex workers the compromises they are willing to make to ensure safe working conditions and the same legal protections afforded to other workers. More of the women might be willing to pay taxes and accept the same regulations as other businesses if they knew it would result in the acquisition of legal protection. This requires further inquiry. It is also probable that marginalized sex workers have not been as visible in previous decriminalization campaigns because their basic needs are not being met, and organizing for legal change is not their immediate priority. Advocacy groups need to work with sex workers – women, men and transgender – who are most marginalized, to understand their immediate needs and how these can be addressed through decriminalization.

Acknowledgements

This study would not have been possible without the participants, who were generous with their time and honesty, as well as the peer-led research staff. We would like to extend our deepest gratitude to Dr Jeff Klausner, Johanna Breyer, Naomi Akers, Charles Cloniger, Dr Willi McFarland, H Fisher Raymond, the St James Infirmary community and the staff at the STD Prevention and Control Unit, San Francisco Department of Public Health. This project was funded by the US National Institute on Drug Abuse (K23DA016174), the UCSF AIDS Research Institute and the UCSF Hellman Award (Cohan, PI). Portions of this paper were presented in poster form at the International AIDS Conference, Mexico City, August 2008, and as an oral presentation at the Desirée Alliance Conference, Las Vegas, Nevada, July 2006.

References

- JD Klausner. Decriminalize prostitution - vote yes on Prop K. San Francisco Chronicle. 8 September. 2008

- I Wolfers. Violence, repression and other health threats: sex workers at risk. Research for Sex Work. 4: 2001; 1–2.

- K Shannon, T Kerr, S Allinott. Social and structural violence and power relations in mitigating HIV risk of drug-using women in survival sex work. Social Science & Medicine. 66: 2008; 911–921.

- P Alexander. Sex workers fight AIDS: an international perspective. BE Schneider, NE Stoller. Women Resisting AIDS: feminist strategies of empowerment. 1995; Temple University Press: Philadelphia.

- P Alexander. Contextual risk versus risk behavior: the impact of the legal, social and economic context of sex work on individual risk taking. Research for Sex Work. 4: 2001; 3–4.

- A Albert. Brothel: The Mustang Ranch and its women. 2001; Random House: New York.

- J Thukral. Decriminalization. MH Ditmore. Encyclopedia of prostitution and sex work. 2006; Greenwood Press: Connecticut, 129.

- A Lutnick. The St. James Infirmary: a history. Sexuality & Culture. 10(2): 2006; 56–75.

- Board of Supervisors of the City and County of San Francisco. San Francisco Task Force on Prostitution: Final Report, 1996.

- <YesOnPropK.org>. Vote November 4, 2008: Yes on Prop K. San Francisco, 2008.

- CBS News. Election results: San Francisco Prop K - decriminalize prostitution. At: <http://elections.cbslocal.com/cbs/kpix/20081104/race2131.shtml. >. Accessed 12 November 2008.

- No on K. No on K: Say no to all human trafficking. San Francisco. At: <http://noonk.net. >. Accessed 12 November 2008.

- J Corbin, A Strauss. Grounded theory research: procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology. 13(1): 1990; 3–21.

- A Strauss, J Corbin. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd ed., 1998; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks.

- D Heckathorn. Respondent-driven sampling: a new approach to the study of hidden populations. Social Problems. 44(2): 1997; 174–199.

- MY Iguchi, AJ Ober, SH Berry. Simultaneous recruitment of drug users and men who have sex with men in the United States and Russia using respondent-driven sampling: sampling methods and implications. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 86(1): 2009; S5–S28.

- AL Crago. Our lives matter: sex workers unite for health and rights. 2008; Sexual Health and Rights Project: Open Society Institute: New York.

- K Demaere. Decriminalisation as partnership: an overview of Australia's sex industry law reform model. Research for Sex Work. 8: 2005; 14–15.

- J Hay. Police abuse of prostitutes in San Francisco. 1994; Gauntlet Magazine: Colorado Springs.

- Sex Workers Project. Unfriendly encounters: street-based sex workers and police in Manhattan, 2005. 2006; Urban Justice Center: New York.

- S Simon, R Thomas. Eight working papers/case studies: examining the intersections of sex work law, policy, rights and health. 2006; Sexual Health and Rights Project: Open Society Institute: New York.

- J Thukral, M Ditmore, A Murphy. Behind closed doors: an analysis of indoor sex work in New York City. 2005; Urban Justice Center, Project SW: New York.

- J Thukral, M Ditmore. Revolving door: an analysis of street-based prostitution in New York City. 2003; Urban Justice Center, Project SW: New York.

- D Cohan, A Lutnick, P Davidson, C Cloniger, A Herlyn, J Breyer. Sex worker health: San Francisco style. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 82: 2006; 418–422.

- K Shannon, T Kerr, SA Strathdee. Prevalence and structural correlates of gender based violence among a prospective cohort of female sex workers. BMJ. 339(b2939): 2009

- KM Blankenship, S Koester. Criminal law, policing policy, and HIV risk in female street sex workers and injection drug users. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 30: 2002; 548–559.

- MS Weinberg, FM Shaver, CJ Williams. Gendered work in the San Francisco Tenderloin. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 28(6): 1999; 503–521.