Abstract

In England and Wales, criminal prosecutions for recklessly causing serious bodily harm by transmitting HIV have occurred since 2003. Understanding how people respond to the application of criminal law, will help to determine the likely impact of prosecution. As part of a wider qualitative study on unprotected anal intercourse amongst homosexually active men with diagnosed HIV in England and Wales, 42 respondents were asked about their awareness of criminal prosecutions for the sexual transmission of HIV, and how (if at all) they had adapted their sexual behaviour as a result. Findings demonstrate considerable confusion regarding the law and suggest that misunderstandings could lead people with HIV to wrongly believe that how they act, and what they do or do not say, is legitimated by law. Although criminalisation prompted some respondents to take steps to reduce sexual transmission of HIV, others moderated their behaviour in ways likely to have adverse effects, or reported no change. The aim of the criminal justice system is to carry out justice, not to improve public health. The question addressed in this paper is whether desirable public health outcomes may be outweighed by undesirable ones when the criminal law is applied to a population-level epidemic.

Résumé

En Angleterre et au Pays de Galles, la transmission du VIH fait l'objet de poursuites pénales pour dommages corporels par imprudence depuis 2003. Comprendre comment la population réagit à l'application du droit pénal aidera à déterminer l'impact probable des poursuites. Dans le cadre d'une étude qualitative plus large sur les rapports anaux non protégés entre homosexuels actifs avec une infection à VIH diagnostiquée en Angleterre et au Pays de Galles, on a demandé à 42 répondants s'ils savaient qu'ils risquaient des poursuites pénales pour transmission sexuelle du VIH et comment (le cas échéant) ils avaient adapté leur comportement sexuel en conséquence. Les conclusions révèlent une confusion considérable quant à la loi et suggèrent que des malentendus pourraient amener des personnes séropositives à penser à tort que ce qu'elles font et ce qu'elles disent ou non est légitimé par la loi. Bien que la criminalisation ait incité quelques répondants à prendre des mesures pour réduire la transmission sexuelle du VIH, d'autres ont modéré leur comportement de façons qui auront probablement des effets négatifs, ou n'ont pas indiqué de changements. L'objectif du système pénal est de rendre la justice, pas d'améliorer la santé publique. Cet article se demande si les conséquences indésirables ne risquent pas de l'emporter sur les résultats souhaitables de santé publique quand le droit pénal est appliqué à une épidémie au niveau de la population.

Resumen

En Inglaterra y en Gales, desde 2003 se interpone acción penal por imprudencia temeraria al causar graves daños corporales mediante la transmisión del VIH. Entender cómo las personas responden a la aplicación del derecho penal ayudará a determinar el probable impacto de la acción judicial. Como parte de un estudio cualitativo más amplio sobre el coito anal sin protección entre los hombres homosexualmente activos diagnosticados con VIH, en Inglaterra y Gales, 42 entrevistados fueron interrogados respecto a su conocimiento de la acción penal por la transmisión sexual del VIH, y cómo (o si) habían adaptado su comportamiento sexual por consiguiente. Los resultados demuestran considerable confusión respecto a la ley e indican que los malos entendidos podrían llevar a las personas con VIH a creer erróneamente que la forma en que actúan y lo que digan o dejen de decir, son legitimados por la ley. Aunque la penalización motivó a algunos entrevistados a tomar medidas para reducir la transmisión sexual del VIH, otros moderaron su comportamiento en formas que probablemente tendrán efectos adversos, o no informaron ningún cambio. El propósito del sistema de justicia penal es hacer cumplir la justicia, no mejorar la salud pública. La interrogante tratada en este artículo es si los resultados deseables para la salud pública pesan menos que los indeseables cuando el derecho penal se aplica a una epidemia a nivel poblacional.

International debate about the likely benefits of criminal prosecution for exposure to and/or transmission of HIV has increased over the past decade in light of a growing number of prosecutions and HIV-related legislation. Some have used economic analyses to explore the optimal extent to which the criminal law should be used in relation to HIV transmission and exposure.Citation1 Others argue that such prosecutions should not increase discrimination against people with HIV,Citation2 or are likely to be limited in scope.Citation3

Those who support criminal prosecution often convey an underlying belief that it will contribute to the public health goal of reducing onward transmission of HIV, by deterring people with HIV from engaging in risky behaviour.Citation4Citation5

“In public health terms, the real question is the message that the criminal law gives out. This should be a message that encourages responsible behaviour in sexual relations. Would criminal liability for the reckless transmission of disease encourage responsible behaviour, or not?” Citation5

“In recent years, a growing number of countries have taken steps to criminalize HIV transmission. In theory, this has been done to prevent the spread of infection. In practice, it has done the opposite – reducing the effectiveness of HIV prevention efforts by reinforcing the stigma. Such measures send the message that people living with HIV are a danger to society.” Citation18

A robust body of research evidence that will help to clarify the issues raised by those on all sides of this debate is only in initial stages of development. Sexual behaviour and HIV prevention needs are complex, and people are open to many influences when making sexual decisions. This makes the empirical assessment of the impact of prosecutions at a population level difficult. It cannot be achieved, for instance, by examining overall HIV testing rates, as the testing patterns of populations are influenced by a wide range of factors that can pull in different directions at the same time.

Survey data collected among more than 6,000 homosexually active men in the UK in 2006 demonstrated that when men were asked to consider their views on prosecutions for HIV transmission, the majority supported prosecutions, and many did so as a result of their concern about the harm caused by transmission, and the responsibility held by people with an HIV diagnosis to disclose their status prior to any sexual contact.Citation20 Few of the respondents reflected on whether prosecutions would help reduce HIV transmission; instead, the overwhelming majority focused on themes related to retribution and punishment.

Qualitative research undertaken in 2005 with 34 gay Canadian men who regularly engaged in unprotected anal intercourse revealed that some actively resisted the implication that people with an HIV diagnosis should have more responsibility for the avoidance of HIV exposure and transmission than their sexual partners, while a similar proportion supported prosecutions.Citation23 Others were concerned that they could face criminal liability for their actions, and described the difficulty of sustaining HIV disclosure in all sexual settings. A further study undertaken with 76 people with HIV in two US cities in the late 1990s revealed a great degree of ambivalence about prosecutions, as well as confusion about the scope of the law.Citation24 While the majority felt that prosecutions might help to reduce HIV transmission, some of the same respondents also disagreed with an exclusive focus on the responsibility of the diagnosed partner and their status disclosure, rather than attending to whether protection was used, while others were concerned that such laws might be abused. These findings were echoed in a focus group study undertaken in the US in 2007 with 31 participants with diagnosed HIV.Citation25 Another investigation based on interviews with more than 400 people who were likely to come into contact with HIV, living in two American states with differing legal approaches to HIV transmission, found that regardless of residence, respondents' beliefs about the law did not influence their sexual behaviour.Citation11 One of the only detailed investigations undertaken to date on awareness of such statutes among people with diagnosed HIV was undertaken between 2005 and 2007 in the United States among 384 people accessing HIV services, and found that the majority had a very high understanding of the circumstances that would result in liability in their jurisdiction.Citation26

Legal context in England and Wales

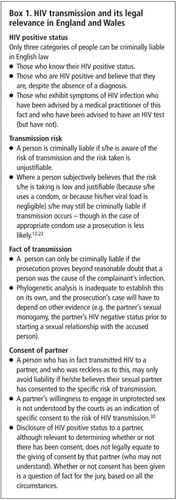

In England and Wales, criminal prosecutions for the transmission of HIV and other serious sexually transmitted infections have occurred since 2003, for recklessly causing serious bodily harm under Section 20 of the Offences Against the Person Act 1861. In this paper we focus on the use of this law to prosecute HIV transmission only. There is no provision for criminally prosecuting those who have exposed someone to the risk of HIV transmission where infection has not occurred, nor is there HIV-specific criminal legislation in this jurisdiction. It is estimated that up to 20 cases have progressed to trial, with scores more investigations having been undertaken and dropped before that stage.Citation21 Many early prosecutions for sexual HIV transmission in England and Wales involved guilty pleas, and resulted in custodial sentences averaging two to three years for each offence, and carrying the potential for deportation for non-citizens. However, since a case in 2006 demonstrated that virological evidence alone is unable to prove the direction or timing of HIV transmission, most cases have been dismissed or the defendant acquitted.Citation27Citation28 Some HIV transmission prosecutions have been launched using Section 18 of the Act in relation to the intentional infliction of harm, but to date no such case has proceeded to trial as the burden of proof that someone intended serious harm is extremely high.

In English law, a person is criminally liable if he or she intentionally or recklessly transmits HIV to another person, and that other person did not consent to the risk of transmission.Citation29 Citation31 This means that to avoid criminal liability a person needs to know what is meant, in legal (rather than in lay) terms by intention, recklessness, causing serious bodily harm and consent. S/he would need to know, for example:

that a person intends a consequence when it is his/her purpose, or (more rarely) where that consequence is (a) virtually certain and (b) s/he realises that it is virtually certain;

that a person is reckless as to a consequence where s/he realises that there is a risk of causing that consequence, and the risk s/he takes is an unjustifiable one;

that s/he is the cause of the harm (i.e. that the harm was not caused by another person), and

that a partner consents to the risk of harm when that partner, in possession of relevant information, makes a conscious or willing decision to bear the risk.Citation10

Research on criminal prosecutions must take particular account of the specifics of the law in the jurisdiction where the research takes place. Understanding how people respond to the application of criminal law in their local context, and what this means with regard to their own behaviour will help to determine the likely impact of those measures. As such, the research described in this paper aims to contribute to the small but growing body of work examining responses to criminal prosecutions for sexual transmission of HIV among those with the greatest proximity to the epidemic.

Methods

The findings described here arise from data collected during in-depth interviews undertaken with 42 men recruited by 10 community-based agencies in England and Wales to investigate experiences of unprotected anal intercourse amongst homosexually active men with diagnosed HIV. A full description of the methods and wider findings of that study are reported elsewhere.Citation32 Telephone screening of interested participants helped to ensure even distributions of men living in high and low HIV prevalence areas, and those who had been diagnosed for longer and shorter periods of time. To be eligible to participate, men were required to have received an HIV diagnosis, and to have participated in unprotected anal intercourse with a man in the last year. Participants' confidentiality was assured and all were given a reimbursement of £20 for their time.

The semi-structured interviews included a range of topics including: the influence of their own and sexual partners' HIV status on sexual risk assessment; details about their most recent experience of unprotected anal intercourse; awareness and experience of HIV risk reduction tactics and technologies; and awareness and personal impact of criminal prosecutions for the reckless transmission of HIV in the UK. Interviews lasted 1-2 hours and took place in Bristol, Exeter, Leeds, Liverpool, London, Stoke-on-Trent, Manchester and Swansea. Each interview was digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Respondents were aged 18-58 years (median 37). Relatively equal proportions had achieved basic secondary school qualifications (n=14), further education through ‘A’ levels or college diplomas (n=16), and university degrees (n=12). More than half (n=24) had no current regular sexual partner; the median number of sexual partners in the 12 months prior to interview was 27.

Here we concentrate on men's prompted and unprompted recounting of their understanding of criminal prosecutions for HIV transmission in the UK, and where further data are available, men's reflections on their own sexual decision-making in light of such prosecutions. Although criminal prosecutions were not the only topic discussed during these interviews, most respondents talked about them in some level of detail. Identification of key themes relating to criminal prosecutions was undertaken by all three researchers (the authors) working independently. Coding and cross-checking of data against these themes was then undertaken with each transcript. Overlaps and/or conflicts were discussed and resolved together.

It might be considered a limitation of these data that they were gained from an opportunistic sample of men in contact with HIV support agencies. Also, the use of an open-ended, responsive topic guide meant that the specificity of questions asked about criminal prosecutions and their behavioural impact varied. Almost all (37 of 42) respondents gave information about their understanding of prosecutions after being asked: “Did you know that in the UK, and elsewhere, people have been prosecuted and convicted for transmitting HIV to another person?…Can you tell me what you understand about these cases and about criminal prosecution for HIV transmission?”

Twenty-nine of the 42 talked about the extent to which criminal cases had caused them to reflect on or change their sexual behaviour after being asked: “Does the possibility of criminal prosecution make any difference to the type of sex you have?”

What we seek to convey from these data, therefore, is a snapshot of men's own accounts of prosecutions, at the same time as we consider their self-described behavioural change resulting from their perceptions of the law.

Knowledge of criminal law

Knowledge is power, and ignorance of the law is no excuse. These two axioms are critical to the present discussion. Knowledge of the law is clearly important for people living with HIV (as Box 1 indicates). However, the respondents demonstrate a range of understandings of the law and its potential impact on them. About a third of the men in the sample articulated awareness of, and accurately expressed, the matters which the prosecution has to prove. Nonetheless, their understanding sometimes contained key flaws. For instance, one respondent believed that “group sex was OK”. Another thought that risky sex while abroad meant he could not be prosecuted.

“I mean unfortunately… I guess because I was in another country I guess I felt… and because it was in a sauna… generally one-off incidents. You feel that in those places they aren't going to come back to you.” (Late 20s, diagnosed 7 years)

“So I had to go to [HIV service organisation] then and say: ‘What is the legal situation?’ You know? ‘I did disclose my status right at the beginning before anything ever happened with him and I did tell him.’ [And they said:] ‘So as long as you've told him that and he was aware of that, then there's nothing much he can do about it. It's up to him. It's his responsibility.’” (Mid-30s, diagnosed 3 years)

These examples demonstrate the kinds of misconceptions still held by those who understood the core elements of the law. More substantial misunderstandings were also common. For instance, most of the men were aware of black African heterosexuals in the UK facing prosecution but did not know that sexual HIV transmission between men could also be prosecuted. Another frequent assumption was that for those with high numbers of concurrent partners, evidence to support a prosecution would be impossible to collect. Perhaps the most profound confusion was among those who wrongly believed that only those who had a premeditated intent to cause HIV transmission risked prosecution. Some others believed that HIV transmission might be considered as rape, sexual assault, murder, manslaughter or attempted manslaughter.

“Well the law's changed now, hasn't it, you know, sex-wise, so if you infect somebody with HIV it's classed as rape basically, isn't it? Because you infect someone with HIV.” (Early 30s, diagnosed 7 years)

These misunderstandings have arisen even among the small number of respondents who said that they had attended information events at HIV community organisations on the topic of criminal prosecutions, and among others who had read press coverage of cases in some detail. Indeed, many national and local newspapers have consistently misreported cases – referring to the non-existent offence of “biological grievous bodily harm”, and equating recklessness with intention.Citation33Citation34

Some men's gaps in information, such as a failure to know the frequency of prosecutions, will have relatively little importance in terms of their own decision-making. However, more substantial mistakes about, for example, the mental element that needs to be proved, the level of sentencing, the idea that risk-taking on the part of others in the absence of disclosure provides a defence, and the privilege associated with medical records can have a significant impact on an individual's assessment of his own behaviour in sexual settings.

Each individual draws on a wide array of factors when determining the degree of risk that a sexual encounter may pose to his partner as well as himself.Citation32 Misunderstanding some of the basic elements of prosecutions led some respondents to underestimate the hazards associated with particular sexual scenarios. If knowledge is power, then the converse is also true. The ignorance of some of the men in this sample has the potential to render them powerless in the face of the criminal law.

The role of criminalisation in men's lives

Of the 29 men who reflected on personal impact, almost half felt that prosecutions had not influenced their sexual behaviour in any way. The rest said they had, or planned to, behave and communicate differently with sexual partners as a direct result of concern at the prospect of legal intrusion into their sex lives. Although some of the changes they mentioned were likely to bring about a reduction in the likelihood of HIV transmission, this was not universally the case.

Altered behaviours and revised meanings

Several men feared condemnation from their local gay community should it become known that they had engaged in unprotected sex as a diagnosed man, particularly if that sex resulted in transmission of HIV. A criminal prosecution case had the potential to make public such behaviour and raised the fear of judgement from peers and the negative social consequences of being identified as morally reprehensible. As a result they were particularly cautious about avoiding the circumstances that might lead to such an accusation.

“I'm very, very acutely aware of kind of where the law is on it, you know? And although I could say that he knew I were positive there, [pause] I could possibly still be ostracised if it came out in the community that I was the one who infected him and all of this sort of stuff. I didn't want that really and I didn't fancy being prosecuted.” (Late 30s, diagnosed 18 years)

“The reason that I like to meet people online is you hear all these court cases with people not telling people they are HIV positive. Because some people on MSM [instant online messaging] have got written confirmation… I keep all my chat logs, yeah.” (Mid-20s, diagnosed 4 years)

However, adaptation of behaviour attributed to criminal prosecutions was not always in a more protective direction. In direct contrast to the men described above, five men responded to the risk of criminal prosecutions by maximising their anonymity, and being less open about their HIV status. They felt that being publicly identifiable as a man with diagnosed HIV placed them at too much risk of prosecution, and were concerned about previous openness about their HIV status within social networks. Concern about the lack of control they now exercised over that personal information meant they were now rarely open about their HIV status among friends and acquaintances. Some modified their online social and sexual network profiles.

“And also on gaydar [a social and sexual networking website for men] I will tell you that I have safe sex as always. Though that isn't necessarily the case. But that is due to laws currently in place by this wonderful country that we live in that will gain access to all your personal information. And if somebody came up and said, ‘Well he transmitted HIV to me’, they will look at gaydar and see what status you put [in your online profile] and what type of sex you put and so on and so forth. And that can be used against you in a court of law. So for that reason I protect myself to the hilt. But I will discuss safe sex with people as and when I see them and as and when I feel that that is necessary.” (Mid-30s, diagnosed <1 year)

“Interviewer: OK. What's your concern about other people finding out, if you see what I mean? What formed your decision not to tell other people [that you have HIV]?

Respondent: I think the biggest single concern is the criminalisation.” (Late 50s, diagnosed <1 year)

“Respondent: The two incidents where this [having unprotected anal intercourse] happened have been in the sauna and on holiday. I'm more conscious around the [local] scene because I don't want any backlash, if you know what I mean.

Interviewer: OK. So it's kind of when it's a bit more anonymous maybe? When like you're not having much personal involvement with them and it's easier to do it in that context, or something you worry about less if it happened in that context?

Respondent: Yeah.” (Early 30s, diagnosed 2 years)

Absence of impact

The nearly half of the 29 respondents who said that prosecutions had not influenced their sexual behaviour were not concerned about the possibility of criminal prosecution. The reasons for this often related to their existing practices, which they felt limited the possibility of a successful case being brought against them. Some of these practices could reduce the likelihood of a criminal complaint being made; while others could increase such a likelihood.

A few men said that even before their awareness of prosecutions, they always ensured that they told sexual partners about their HIV status, and felt that sharing such information with partners was the right thing to do. Others said they only engaged in sexual behaviours that were unlikely to result in new infections and as a result, did not feel that prosecutions would relate to them

“I'd still tell somebody, whether or not I needed to legally.” (Mid-20s, diagnosed <1 year)

“I have safe sex unless I know somebody is HIV positive. You know, I try and lessen the risk. But I don't know. Maybe, I think I've altered, altered the way I behave myself. But I don't think it's anything to do with prosecutions.” (Late 50s, diagnosed 10 years)

“I remember saying: ‘You know we should use a condom’, especially after, you know. ‘We should use a condom.’ But I never said to him that I was HIV.” (Late 30s, diagnosed 10 years)

“I kind of make an assumption that when they're doing the kind of things that they're doing, in the setting with people that they are, some of whom… they're obviously positive. Then it's, kind of like, taking it as read for me that they basically are.” (Late 20s, diagnosed 3 years)

A small group of men lacked either the motivation or the capacity to respond to the possibility that they could be held legally liable for their actions. One particularly young respondent, with some degree of cognitive impairment, lacked the essential skills required to take control over sexual interactions, and most of his sexual encounters were dictated by the desires of his partners.

Consistent disclosure of HIV status in all sexual contexts was regarded by many respondents as unrealistic. Some rationalised this by contending that this was not expected by sexual partners and therefore, there was little reason to expect criminal investigation as a result.

“I don't think I really thought a great deal about it in terms of my own behaviour since then. Largely because nobody I've met… it's not an issue for them. You know, they're not saying to me ‘Fill in a form, I need to know all the statistics, your viral load, do a risk assessment, get you to sign things.’ Nobody's doing that. We're just having sex.” (Mid-30s, diagnosed 3 years)

Discussion

These findings demonstrate some of the key challenges in seeking to influence human behaviour. One third of the men in this sample had a fairly accurate understanding of the law as it applies to HIV transmission in England and Wales; the majority did not. Where pervasive misunderstandings exist, it is hard to see how many of these respondents with diagnosed HIV who engage in unprotected anal intercourse with high numbers of sexual partners can ensure that they avoid prosecution.

Establishing the way in which men modified their behaviour in light of prosecutions was more complex. While the possibility of prosecution meant that some of the men increased explicit HIV disclosure or took other measures to reduce transmission risk, there were also those who moved toward increased anonymity during sex, and decreased disclosure of their HIV status. This demonstrates the capacity for criminalisation to re-inscribe the stigma that is associated with HIV. The remainder of men in the sample felt that their actions were already safe, and that the law had little bearing on their own behaviour. However, the misjudgements and flawed sexual risk assessments made by some men in each of these categories persist. A small number of men with pervasive and diffuse HIV prevention needs lacked the capacity or motivation to reduce the likelihood of transmission, despite the threat of prosecution. Thus, while not all of the news about the impact of criminalisation is bad, there is a need to consider how this stacks up against reduced openness and the failure of criminalisation to address the deeply flawed risk assessments made by many of the men described here.

The aim of the criminal justice system is to carry out justice, not to improve public health. However, the pursuit of justice can sometimes conflict with the protection of public health. By legitimating risk-taking via consent and disclosure (and criminalising the converse when transmission in fact occurs) the law affirms the need to disclose and to gain consent. The problem is that in the absence of a clear understanding of what this means – or where other, competing priorities such as being free of the stigma associated with HIV take precedence – some diagnosed people will place themselves at risk of prosecution. In drawing attention to this, we do not assert that such a person wants to harm his partners – the data do not support such a conclusion. But they do suggest that some people's misunderstanding could lead them to think wrongly that their actions (and inactions) are not prohibited by law.

The law in this area certainly has consequences, but some of these will be undesired, and the question is whether or not the desired outcomes will be outweighed by the undesired ones in relation to a population-level epidemic.

“The criminalization of HIV has been a strange, pointless exercise in the long fight to control HIV. It has done no good; if it has done even a little harm the price has been too high.” Citation11

Acknowledgements

Ethics approval for this project was granted by the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee, University of Portsmouth. The study was funded by Terrence Higgins Trust as part of CHAPS, the national gay men's HIV prevention partnership in England. Peter Keogh, Peter Weatherburn and Gary Hammond also contributed to the Relative Safety II study,Citation32 from which the data are drawn. We are thankful to all the participants for sharing their thoughts and experiences, and all of the HIV charities for helping with recruitment.

References

- AM Francis, HM Mialon. The optimal penalty for sexually transmitting HIV. Emory Law and Economics Research Paper No.08-29. 2008. At: <http://ssrn.com/abstract=1091790. >. Accessed 31 August 2009.

- JR Spencer. Liability for reckless infection: part 1. New Law Journal. 154(7119): 2004; 384–385.

- J Chalmers. The criminalisation of HIV transmission. Journal of Medical Ethics. 28: 2002; 160–163.

- TW Tierney. Criminalizing the sexual transmission of HIV: an international analysis. Hastings International and Comparative Law Review. 15: 1991-2; 475–513.

- JR Spencer. Liability for reckless infection: part 2. New Law Journal. 157(7121): 2004. 448,471.

- S Burris, E Cameron, M Clayton. The criminalization of HIV: time for an unambiguous rejection of the use of criminal law to regulate the sexual behaviour of those with and at risk of HIV. Social Science Research Network 2008. At: <http://ssrn.com/abstract=1189501. >. Accessed 31 August 2009.

- R Pearshouse. Legislation contagion: the spread of problematic new HIV laws in Western Africa. HIV/AIDS Policy & Law Review. 12(2-3): 2008; 5–11. At: <www.aidslaw.ca/publications/interfaces/downloadFile.php?ref=1275. >. Accessed 31 August 2009.

- UNAIDS. Criminalisation of HIV transmission: policy brief. 2008; UNAIDS: Geneva. At: <http://data.unaids.org/pub/BaseDocument/2008/20080731_jc1513_policy_criminalization_en.pdf. >. Accessed 31 August 2009.

- MA Wainberg. HIV transmission should be decriminalized: HIV prevention programs depend on it. Retrovirology. 5: 2008; 108. At: <www.retrovirology.com/content/5/1/108. >. Accessed 31 August 2009.

- M Weait. Intimacy and responsibility: the criminalisation of HIV transmission. 2007; Routledge-Cavendish: Abingdon.

- SC Burris, L Beletsky, JA Burleson. Do criminal laws influence HIV risk behaviour? an empirical trial. Arizona State Law Journal. 39: 2007; 467–517. At: <http://ssrn.com/abstract=977274. >. Accessed 31 August 2009.

- J Anderson, J Chalmers, M Nelson. HIV transmission, the law and the work of the clinical team: a briefing paper. 2006. At: <www.bhiva.org/files/file1001327.pdf. >. Accessed 31 August 2009.

- R Lowbury, GR Kinghorn. Criminal prosecution for HIV transmission: a threat to public health. BMJ. 333(7570): 2006; 666–667. At: <www.bmj.com/cgi/content/extract/333/7570/666?ehom=. >. Accessed 31 August 2009.

- World Health Organization. WHO technical consultation in collaboration with the European AIDS Treatment Group and AIDs Action Europe on the criminalization of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. 2006; WHO: Copenhagen. At: <www.euro.who.int/Document/SHA/crimconsultation_latest.pdf. >. Accessed 31 August 2009.

- C Dodds, P Weatherburn, P Keogh. Grevious harm: use of the Offences Against the Person Act 1861 for sexual transmission of HIV. 2005; Sigma Research: London. At: <www.sigmaresearch.org.uk/go.php/reports/report2005b. >. Accessed 31 August 2009.

- R Elliott. Criminal Law, Public Health and HIV Transmission: a policy options paper. 2002; UNAIDS: Geneva. At: <http://data.unaids.org/publications/IRC-pub02/JC733-CriminalLaw_en.pdf. >. Accessed 31 August 2009.

- SJ Bray. Criminal prosecutions for HIV exposure: overview and analysis. Working Paper 3(1). 2003; Yale University Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS: New Haven. At: <www.hivlawandpolicy.org/resources/view/218. >. Accessed 31 August 2009.

- K-M Ban. Secretary General's remarks at UN General Assembly HIV/AIDS review. 16 June 2009. At: <www.un.org/apps/sg/sgstats.asp?nid=3929. >. Accessed 10 September 2009.

- C Dodds, P Keogh. Criminal convictions for HIV transmission: people living with HIV respond. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 17(5): 2006; 315–318.

- C Dodds, P Weatherburn, A Bourne. Sexually charged: the views of gay and bisexual men on criminal prosecutions for sexual HIV transmission. 2009; Sigma Research: London. At: <www.sigmaresearch.org.uk/go.php/reports/report2009a/. >. Accessed 31 August 2009.

- L Power. Policing transmission: a review of police handling of criminal investigations relating to transmission of HIV in England and Wales, 2005-2008. 2009; Terrence Higgins Trust: London. At: <www.tht.org.uk/informationresources/publications/policyreports/policingtransmission950.pdf. >. Accessed 31 August 2009.

- Crown Prosecution Service. Policy for prosecuting cases involving the intentional or reckless sexual transmission of infection. 2008; CPS: London. At: <www.cps.gov.uk. >. Accessed 31 August 2009.

- BD Adam, R Elliott, W Husbands. Effects of the criminalization of HIV transmission in Cuerrier on men reporting unprotected sex with men. Canadian Journal of Law and Society. 23(1-2): 2008; 143–159.

- R Klitzman, S Kirshenbaum, L Kittel. Naming names: perceptions of name-based HIV reporting, partner notification, and criminalization of non-disclosure among persons living with HIV. Sexuality Research & Social Policy. 1(3): 2004; 38–57.

- CL Galletly, J Dickson-Gomez. HIV sero-postive status disclosure to prospective sex partners and criminal laws that require it: perspectives of persons living with HIV. International Journal of STI & AIDS. 20: 2009; 613–618.

- Galletly CL, DiFranciesco W, Pinkerton SD. HIV-positive persons' awareness and understanding of their state's criminal HIV disclosure law. AIDS & Behaviour. (in press).

- M Carter. Prosecution for reckless HIV transmission in England ends with not guilty verdict. 2006; NAM: London. At: <www.aidsmap.com/en/news/9770EEA6-020F-440A-9224-D7BAD7784A69.asp. >. Accessed 31 August 2009.

- E Bernard. Reckless HIV transmission case dismissed due to insufficient evidence. 2008; NAM: London. At: <www.aidsmap.com/en/news/E6CA55A4-C909-4B4E-9916-4A3B30BA6C53.asp. >. Accessed 31 August 2009.

- Offences Against the Person Act 1861, sections 18 and 20.

- R v Dica [2004] 2 Cr. App. R. 28.

- R v Konzani [2005] 2 Cr. App. R.14.

- A Bourne, C Dodds, P Keogh. Relative safety II: risk and unprotected anal intercourse among gay men with diagnosed HIV. 2009; Sigma Research: London. At: <www.sigmaresearch.org.uk/go.php/reports/report2009d/. >. Accessed 31 August 2009.

- HIV man jailed for infecting lovers. BBC News Website. 3 November 2003. At: <http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/london/3236501.stm. >. Accessed 31 August 2009.

- K McVeigh. Warrant out for missing man who passed on HIV. The Times. 27 July 2006. At: <www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/uk/article693411.ece. >. Accessed 31 August 2009.