Abstract

Unsafe abortion in Sudan results in significant morbidity and mortality. This study of treatment for complications of unsafe abortion in five hospitals in Khartoum, Sudan, included a review of hospital records and a survey of 726 patients seeking abortion-related care from 27 October 2007 to 31 January 2008, an interview of a provider of post-abortion care and focus group discussions with community leaders. Findings demonstrate enormous unmet need for safe abortion services. Abortion is legally restricted in Sudan to circumstances where the woman's life is at risk or in cases of rape. Post-abortion care is not easily accessible. In a country struggling with poverty, internal displacement, rural dwelling, and a dearth of trained doctors, mid-level providers are not allowed to provide post-abortion care or prescribe contraception. The vast majority of the 726 abortion patients in the five hospitals were treated with dilatation and curettage (D&C), and only 12.3% were discharged with a contraceptive method. Some women waited long hours before treatment was provided; 14.5% of them had to wait for 5-8 hours and 7.3% for 9-12 hours. Mid-level providers should be trained in safe abortion care and post-abortion care to make these services accessible to a wider community in Sudan. Guidelines should be developed on quality of care and should mandate the use of manual vacuum aspiration or misoprostol for medical abortion instead of D&C.

Résumé

Les avortements à risque au Soudan provoquent une morbidité et une mortalité importantes. Cette étude du traitement des complications de l'avortement à risque dans cinq hôpitaux de Khartoum, Soudan, a examiné des dossiers hospitaliers et enquêté auprès de 726 patientes ayant demandé des soins liés à l'avortement du 27 octobre 2007 au 31 janvier 2008. De plus, un entretien a eu lieu avec un prestataire de soins post-avortement et des discussions de groupe avec des responsables communautaires. L'étude révèle un énorme besoin insatisfait de services d'avortement sûr. La loi soudanaise limite l'avortement aux grossesses résultant d'un viol ou mettant en danger la vie de la femme. Il est difficile d'avoir accès aux soins post-avortement. Dans un pays rural aux prises avec la pauvreté, les déplacements internes et une pénurie de médecins formés, les prestataires de niveau intermédiaire ne sont pas autorisés à donner des soins post-avortement ou à prescrire des contraceptifs. La grande majorité des 726 patientes ont avorté par dilatation et curetage et seulement 12,3% sont sorties de l'hôpital avec une méthode de contraception. Quelques femmes devaient attendre longtemps avant d’être traitées ; 14,5% d’entre elles avaient dû patienter pendant 5-8 heures et 7,3% pendant 9-12 heures. Les prestataires de niveau intermédiaire doivent être formés à l'avortement sûr et aux soins post-avortement afin que ces services soient accessibles à davantage de Soudanaises. Il faut préparer des directives sur la qualité des soins et rendre obligatoire l'utilisation de l'aspiration manuelle ou du misoprostol pour l'avortement médicamenteux, de préférence à la méthode par dilatation et curetage.

Resumen

El aborto inseguro en Sudán causa considerable morbilidad y mortalidad. Este estudio del tratamiento de las complicaciones del aborto inseguro en cinco hospitales de Jartum, en Sudán, comprendió una revisión de los registros hospitalarios, una encuesta de 726 pacientes que buscaban servicios de aborto entre el 27 de octubre de 2007 y el 31 de enero de 2008, una entrevista de un proveedor de atención postaborto y discusiones en grupos focales con líderes de la comunidad. Los resultados demuestran la enorme necesidad insatisfecha de servicios de aborto seguro. En Sudán, el aborto es limitado por la ley a circunstancias en que la vida de la mujer corre peligro o casos de violación. La atención postaborto no es fácil de acceder. En un país donde se lucha contra la pobreza, el desplazamiento interno, viviendas rurales y una escasez de médicos capacitados, a los prestadores de servicios de nivel intermedio se les prohíbe brindar atención postaborto o recetar anticonceptivos. La gran mayoría de las 726 pacientes encuestadas en los cinco hospitales fueron tratadas con dilatación y curetaje (D&C) y sólo el 12.3% recibió un método anticonceptivo antes de egresar. Unas de las mujeres tuvieron que esperar largas horas antes de recibir tratamiento. El 14.5% tuvo que esperar 5-8 horas; el 7.3%, 9-12 horas. Los prestadores de servicios de nivel intermedio deberían recibir capacitación en la atención segura del aborto y la atención postaborto para ampliar el acceso a estos servicios en Sudán. Se deberían elaborar directrices sobre la calidad de la atención, que exijan el uso de la aspiración manual endouterina o el misoprostol en los procedimientos de aborto con medicamentos, en vez de D&C.

In Sudan, due in part to infrastructural weaknesses in health care and decades of civil strife, no national data exist on sexual and reproductive health, including on induced and unsafe abortion. With a high number of internally displaced persons living in environments characterised by poverty and gender-based violence, access to health services is often tenuous. In some situations, women and girls submit to sexual abuse in order to obtain food and basic necessities.Citation1 In addition, a restrictive abortion law coupled with strong cultural and religious stigma against abortion mean not only that it is difficult to access safe abortion services, but also that it is difficult for people to speak openly about the topic at the community level, let alone to gather information.

Abortion is legal in Sudan only in cases of rape and when the woman's life is at risk. In cases of rape, the woman must inform the police immediately, who should then provide her with a form (Form No.8), which, in the event of pregnancy, she can take to the nearest hospital for the assurance of a safe abortion. Post-abortion care (PAC) is also allowed in Sudan.

Women in Sudan seek unsafe abortions for a range of reasons, including lack of knowledge about their rights under the law, lack of access to safe services and lack of resources to access safe services. This is probably as true now as it was in 1976, when one of the few studies on this subject was published.Citation2 Post-abortion care (PAC) is at its best a comprehensive strategy to address the problem of unsafe abortion, including treatment of complications caused by unsafe procedures, provision of post-abortion contraceptives, and engagement of the community on these issues.Citation3 Treatment for most complications can be carried out by mid-level providers, including nurses and midwives, with training. PAC is widely permitted in countries where abortion is legally restricted and when widely available, can be a key life-saving intervention for women.Citation4Citation5

Several international and regional human rights frameworks, including the African Union's Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Continental Policy Framework and the Maputo Protocol, provide clear guidelines for addressing the issue of unsafe abortion, framing access to safe abortion, including post-abortion care, and other reproductive rights as human rights.Citation6Citation7 Despite this, few African countries have reproductive health laws that allow access to safe abortion services or adequately ensure access to quality post-abortion care. Even in countries where the law more liberally allows for access to safe abortion, such as in Ethiopia and South Africa, stigma and conscientious objection by providers continue to restrict access in practice.Citation8

Unintended pregnancy rates are high in Sudan. This is due in part to an extremely low contraceptive prevalence rate – fewer than 10% of women of reproductive age use contraceptionCitation9 – but also due to the high level of displacement among much of the population, for whom there is a lack of access to contraceptive services. Current estimates suggest that 4.9 million people are internally displaced as a result of ongoing conflicts – with 250,000 new cases in Southern Sudan in 2009 alone.Citation10 Women and girls who are internally displaced are particularly vulnerable to sexual violence and rape, which contributes to unintended pregnancy and often unsafe abortions.Citation8 Citation11 These and other factors, including the restrictive abortion law, mean that Sudan has one of the highest maternal mortality ratios in the world, estimated by UNICEF to be 1,107 deaths per 100,000 live births,Citation12 a significant proportion of which may be attributed to unsafe abortion.

In Sudan, the majority of the population live in rural, impoverished areas, where doctors are few and where mid-level providers, including midwives and nurses, form the backbone of the health care system, providing for the vast majority of primary health care needs. From 1990 to 2004, it was estimated that there were just 22 doctors per 100,000 people in Sudan, a figure which may not include the south of the country,Citation13 where the situation is worse. Current protocols dictate, however, that legal abortion, post-abortion care and the prescription of contraceptives must be provided only by doctors in Sudan. The practical effect of these guidelines is to restrict access to services for much of the population.

The study

The study was conducted in collaboration with Safe International, a local non-governmental organisation based in Khartoum, as a baseline study to guide future project implementation. It was carried out over a period of three months, between 27 October 2007 and 31 January 2008. The aim was to gather new information on safe abortion services and PAC in Sudan, the quality of care provided, the methods of abortion used, and the characteristics of the women seeking these services, in five referral hospitals in Khartoum. Secondly, it aimed to discover attitudes and knowledge of community leaders on abortion.

Due to limited resources, the study was limited to Khartoum as part of a larger, planned reproductive health project. As the capital of Sudan and a centre of economic opportunity, Khartoum has a diverse population, comprised of internally displaced people and people from all over the country. Thus, the information gathered will represent, at least to some degree, a wider range of communities, and can be used to inform interventions to improve access to safe abortion services beyond Khartoum.

In addition to review of hospital medical records, the study relied on a survey of women admitted to the study hospitals for abortion or post-abortion care. Due to the cultural sensitivity and criminalisation of abortion in Sudan, the veracity of this self-reported data may be undermined, particularly among women who have undergone induced abortions outside the parameters of the law and who have then presented with complications to the hospital. Even data such as marital status may have been self-censored, to avoid stigma.

Data and methods

Several data collection methods were used, including a survey of women patients, aged 15-49, seeking abortion or post-abortion care during the three-month study period at one of five hospitals in Khartoum, collection of data from their hospital medical records, focus group discussions with community leaders and an in-depth interview with a mid-level provider.

The survey was field tested with a sample of 50 patients. The inclusion criteria for survey participants included women aged 15-49 from communities in both Northern and Southern Sudan, Muslims and non-Muslims, who had obtained abortion services at Khartoum Teaching Hospital, Academy Charity Hospital, Ibrahim Malik Hospital, Bashir Hospital and Turkey Hospital in Khartoum. 726 women agreed to participate.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Sudan University of Sciences and Technology, as well as from all five hospitals, which reviewed the protocol. Verbal consent to participate was given by all participants. Patients were reassured that their names and information would remain confidential for study purposes, and data collectors were trained and supervised to enforce confidentiality. Quantitative data were analysed using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Science). Qualitative analysis used a focus group analysis guide.Citation14

In order to determine diagnosis and treatment initially, hospital records were reviewed for the 726 women. Data obtained included marital status, education level, occupation, reproductive history, including parity, gestation, circumcision, and method of contraception used. Records were also analysed for presenting complaints, results of physical examination upon presentation, intervention treatment, type of anaesthesia, and recovery notes made by the doctor.

All 726 patients whose records were reviewed answered survey questions on overall patient satisfaction, friendliness of staff, adequacy of information on abortion provided, privacy of services, ability of staff to answer their questions, waiting time, level of acceptability of pain from the procedure, counselling and information on contraception, provision of a method, and whether a follow-up appointment was scheduled.

Opinion leaders from both Muslim and Christian communities in Khartoum, both women and men, were contacted through referral and invited to participate in the study. Seven men and eight women agreed. They were divided by sex into two focus groups for discussion, in order to provide a greater degree of confidentiality and comfort in expression of opinions. The two groups were asked about the definition of abortion, their knowledge of the abortion law in Sudan, their knowledge of traditional methods of inducing abortion, the extent of abortion, and what the complications were of unsafe abortion performed in the community. In addition, one mid-level provider trained in post-abortion care was interviewed on the practice of mid-level providers with regard to contraception, post-abortion care and provision of abortions.

Women who came for abortion care and services provided

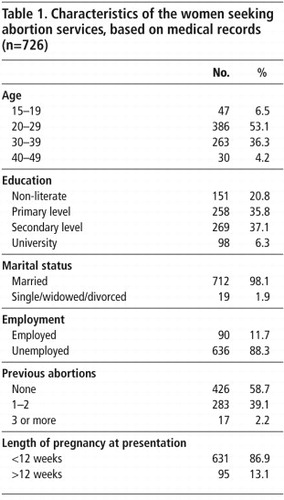

Most of the women seeking abortion services were aged 20–39, had completed primary or secondary education, and were married and unemployed (Table 1

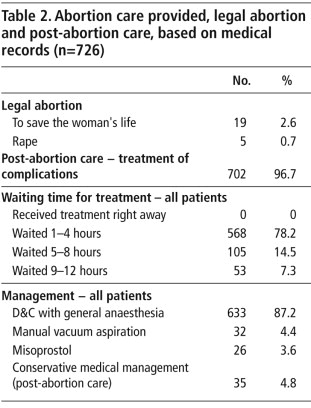

). Most had had either none or 1-2 previous abortions. Incomplete abortion due to unsafe procedures is clearly an issue in Khartoum, as the vast majority of the women seeking services (96.7%) came for treatment of post-abortion complications (Table 2 ). Presenting complaints recorded included multiple symptoms of vaginal bleeding, fever and abdominal pain. Four women had foreign bodies still embedded in their uterus when admitted.The quality of care of these services is also clearly an issue, including long waiting times reported by the women, use of D&C in almost all cases for treatment, and low levels of contraceptive counselling and uptake of a method (Table 2). Women waited long hours before treatment was provided; 53 of them had to wait for 9-12 hours. The majority of women (87.2%) had a D&C with general anaesthesia; only 4.4% were treated with MVA and 3.6% with misoprostol for both post-abortion and safe abortion care.

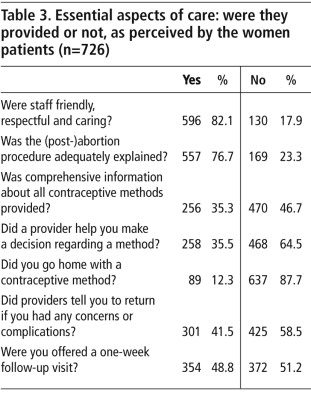

Most staff were perceived as respectful and caring, and explained the abortion procedure sufficiently to satisfy most of the women, but less than half the women said they were offered a follow-up appointment or told to come back if they experienced further complications or had other concerns. Only a third were given contraceptive information and counselling and only 12.3% went home with a contraceptive method (Table 3).

Knowledge and perceptions of community leaders and a mid-level provider

There is widespread knowledge of abortion at all levels of the community and recourse to abortion is quite common, according to the community leaders interviewed. Unsafe abortion is increasingly being seen as a serious social and public health issue in Sudan. They also acknowledged the often fatal consequences of unsafe abortion.

“Yes, I've heard and seen many of the complications of abortion. The main causes of abortion complications seem to be resulting from the use of herbs, and the inadequacy, inaccessibility and unaffordability of proper care. Complications of abortion start from severe abdominal pain and severe bleeding, infection and ultimately can lead to death. Those who do not die from unsafe abortion usually become infertile or develop some kind of disease.” (Woman, age 36)

“Women feel more comfortable going to midwives because they just pay and in return can abort secretly. But when they go to doctors they will be insulted and even abused. For this reason, [women] often prefer being treated by an untrained provider rather than going to a trained doctor.” (Woman, age 40)

The in-depth interview with the mid-level provider trained in post-abortion care revealed the disparity between the accessibility of mid-level providers for the majority of the population, and the strict limits on the services they are able to provide. Because contraceptives are legally prescribed only by doctors, they often write out the prescription and refer patients to mid-level providers, who fill the prescription and distribute methods. On the other hand, although mid-level providers are not legally allowed to provide surgical services such as post-abortion care using MVA, some mid-level providers have been trained by non-governmental organisations, but are not yet able to provide such services openly.

Discussion

Currently, a small number of doctors are providing safe abortion and post-abortion care to a small number of women in hospital settings. In contrast, mid-level providers, including nurses and midwives, are accessible at the community level and are often the first choice of women needing abortions who are concerned about stigma, confidentiality and the discomfort of accessing services in a hospital setting. Although these providers are not allowed to offer legal abortions or post-abortion care services, some are clearly doing so and it would be far better for them to be permitted to do so, so that their training can be ascertained and they can be held accountable for providing good quality services. Many more nurses and midwives have the capacity to be trained, and both these steps would enable far greater access to safe services for women in the wider community, especially in rural areas where doctors are scarce.

Quality of care even in the hospital setting is a critical issue. While some women waited only an hour for treatment, others waited up to 12 hours, suggesting either understaffing, a lack of resources or a lack of urgency in managing incomplete abortion. Further research is needed to ascertain the reasons for these delays in Khartoum's hospitals. A recent study in Gabon also found delays in provision of treatment for complications of unsafe abortion in the main maternity hospital in Libreville, a mean wait of almost 24 hours.Citation15 In that case, lack of staffing and resources were not an issue. The authors of that study state:

“It appears that in the difficult environment of an overcrowded maternity ward, where several emergency cases may compete for attention, the stigma of illegal abortion may lead staff to overlook women with abortion complications without considering the potentially fatal consequences of doing so.” Citation15

MVA and medical abortion are safer and less expensive than D&C, and do not require general anaesthesia. The widespread reliance on D&C for most abortions in all five hospitals, a method that is obsolete in the developed world, is antiquated and unsafe. The World Health Organization (WHO) has long recommended that all first trimester terminations should be carried out either medically (using mifepristone and misoprostol or misoprostol alone) or with MVA.Citation17 Yet most of the women in this study, of whom more than 86% were in the first trimester, underwent evacuation of the uterus using D&C. It is therefore important to advocate that the government amend current guidelines and regulations, in line with WHO recommendations mandating the use of MVA and medical abortion and disseminate them widely to providers, in order to ensure the effectiveness, safety and accessibility of services. Services should be monitored regularly to ensure protocols are being followed.

Lastly, women in Sudan should be informed of their right to have a safe abortion within the law, and cultural and other beliefs that stand in their way must be addressed. Safe abortion services must be available within the law and easily accessible to all women. In addition, the government should review the law to expand indications for safe abortion.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Dr Bashir A Bashir, the consultant in the study, data collection and analysis team: Hanan Satti, Eshrga Baldo, Mohamed Uthman, and many stakeholders including religious leaders, community leaders and service providers. Thank you also to Dr Sarah Onyango, for supporting PPFA's programme work in Sudan.

References

- Human Rights Watch. Sexual violence and its consequences among displaced person in Darfur and Chad. April 2005. At: <http://hrw.org/backgrounder/africa/darfur0505/darfur0405.pdf. >. Accessed 18 May 2009.

- HM Rushwan, JG Ferguson Jr, EH El Nahas. Clinical and epidemiological aspects of incomplete abortion in Khartoum. 1976; University of Khartoum: Sudan.

- Postabortion Care Consortium Community Task Force. Essential elements of postabortion care: an expanded and updated model. PAC in Action 2002. No.2, Special Supplement.

- M Berer. Provision of abortion by mid-level providers: international policy, practice and perspectives. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 87(1): 2009; 58–63.

- Wood M; Ottolenghi E; Marin C, et al. What works: a policy and program guide to the evidence on postabortion care. United States Agency for International Development Postabortion Care Working Group, February 2007.

- African Union Commission. Draft Continental Policy Framework for the Promotion of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights in Africa. August 2005. CAMH/EXP/4 (II). At: <www.africa-union.org/Social%20Affairs/African%20Ministers%20of%20Health%202005/RH%20Policy%20Framework%20-%2015.9.05.pdf. >. Accessed 20 October 2009.

- Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa. African Union. Adopted by the 2nd Ordinary Session of the Assembly of the Union. Maputo, 11 July 2003. At: <www.africa-union.org/root/au/Documents/Treaties/Text/Protocol%20on%20the%20Rights%20of%20Women.pdf. >. Accessed 20 October 2009.

- T Fetters. Abortion care needs in Darfur and Chad. Forced Migration Review. 25(5): 2006. At: <www.reliefweb.int/rwarchive/rwb.nsf/db900sid/KHII-6PG4MG?OpenDocument&query=Fetters&cc=sdn. >. Accessed 13 May 2009.

- J Austin, S Guy, L Lee-Jones. Reproductive health: a right for refugees and internally displaced persons. Reproductive Health Matters. 16(31): 2008; 10–21.

- Internal Displacement Monitoring Center. Sudan. 2008. At: <www.internal-displacement.org/8025708F004CE90B/(httpCountries)/F3D3CAA7CBEBE276802570A7004B87E4?opendocument. >. Accessed 11 July 2009.

- Federal Ministry of Health; Central Statistical Bureau, North of Sudan and Ministry of Health; Southern Sudan Commission for Census and Statistics. Khartoum, 2007.

- UNICEF. Sudan: background. At: <www.unicef.org/infobycountry/sudan_background.html. >. Accessed 20 October 2009.

- The Economist Intelligence Unit. Sudan Country Profile. 2007

- T Dudley, N Phillips. Focus Group Analysis Guide: A Guide for HIV Community Planning Group Members. 1999; University of Texas-Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas. At: <www8.utsouthwestern.edu/vgn/images/portal/cit_56417/19/62/205397Guide_for_Focus_Group_Analysis.pdf. >.

- S Mayi-Tsonga, L Oksana, I Ndombi. Delay in the provision of adequate care to women who died from abortion-related complications in the principal maternity hospital of Gabon. Reproductive Health Matters. 17(34): 2009; 65–70.

- H Youssef, N Abdel-Tawab, J Bratt. Linking family planning with postabortion services in Egypt: testing the feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness of two models of integration. August. 2007; Population Council, Frontiers in Reproductive Health: Cairo.

- World Health Organization. Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems. 2003; WHO: Geneva.