Abstract

Criminalisation is but one of the tools employed by governments to regulate sex and sexuality. Other types of regulation can equally have an impact on health and well-being and thus merit consideration. While restrictive laws related to sexuality are often driven by moral argumentation, public health evidence and human rights norms highlight the need for supportive legal and policy environments. International legal commitments can serve as a check against national laws and policies which do not conform to international consensus. Reporting mechanisms which draw attention to affected populations in the context of HIV have provided a lens through which governments can begin to see the harms to health and well-being caused by their own regulation of sexuality. A review of 2008 self-reported legal and policy data from the 133 countries reporting under the Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS offers important insights. International and national legal and policy environments relating to sexuality are evolving. By identifying dissonance between international standards and national laws and policies, a refocusing of efforts is possible, aiding governments to meet their international obligations and ensuring an appropriate environment for the free and safe expression of sexuality.

Résumé

La criminalisation n'est que l'un des moyens employés par les gouvernements pour réguler les rapports sexuels et la sexualité. D'autres domaines régulés peuvent aussi avoir un impact sur la santé et le bien-être et méritent donc d'être examinés. Si les lois restrictives relatives à la sexualité sont souvent motivées par une argumentation morale, les données de santé publique et les normes des droits de l'homme mettent en lumière la nécessité d'environnements juridiques et politiques propices. Les engagements juridiques internationaux peuvent servir de référence au regard des lois et politiques nationales qui ne sont pas conformes au consensus international. Les mécanismes d'établissement des rapports qui attirent l'attention sur les populations touchées dans le contexte du VIH ont fourni une loupe à travers laquelle les gouvernements peuvent commencer à voir les dommages pour la santé et le bien-être causés par leur propre régulation de la sexualité. Un examen des données juridiques et politiques communiquées en 2008 par les 133 pays ayant présenté un rapport au titre de la Déclaration d'engagement sur le VIH/sida donne des indications précieuses. Si l'on identifie les contradictions entre les normes internationales et les lois et politiques nationales, il est possible de recentrer les activités et d'aider les gouvernements à s'acquitter de leurs obligations internationales tout en garantissant un environnement favorable à une expression libre et sûre de la sexualité.

Resumen

La penalización es sólo una de las herramientas empleadas por los gobiernos para regular las relaciones sexuales y la sexualidad. Otras áreas reguladas pueden tener un impacto en la salud y el bienestar por igual; por ello, merecen tomarse en consideración. Aunque las leyes restrictivas relacionadas con la sexualidad a menudo son regidas por argumentación moral, la evidencia en salud pública y las normas de derechos humanos destacan la necesidad de leyes y políticas favorables. Los compromisos jurídicos internacionales pueden servir de control de las leyes y políticas nacionales que no cumplen con el consenso internacional. Los mecanismos de informes que señalan a las poblaciones afectadas en el contexto del VIH, ofrecen un lente mediante el cual los gobiernos pueden comenzar a ver los daños a la salud y el bienestar causados por su propia regulación de la sexualidad. El análisis de los datos autoinformados en 2008 sobre las leyes y políticas de 133 países, que informaban de acuerdo con la Declaración de compromiso en la lucha contra el VIH/SIDA, nos ayuda a comprender mejor la situación. Las leyes y políticas internacionales y nacionales relacionadas con la sexualidad están evolucionando. Al identificar la discordancia entre las normas internacionales y las leyes y políticas nacionales, es posible redirigir los esfuerzos, ayudando a los gobiernos a cumplir con sus obligaciones internacionales y asegurando un ambiente propicio para la segura y libre expresión de la sexualidad.

The scope of behaviours that fall under governmental regulation of sex and sexuality is broad and raises a multitude of health and human rights concerns.Citation1–3 The HIV pandemic, in which one of the primary modes of transmission is unprotected sex, draws attention to the importance of knowing how sex and sexuality are regulated within and across countries. Laws and policies can facilitate or impede efforts to address HIV by affecting access to health information and services as well as health status. While national frameworks often criminalise specific sexual behaviours, HIV has provided a lens through which the harms caused to the health and well-being of individuals and populations can be seen.

Criminalisation is but one of the regulatory tools employed by governments in relation to sex and sexuality. For example, national or local policies that prohibit contraceptive sales, including condoms, to unmarried persons can impede efforts to prevent HIV prevention among non-married people, including men who have sex with men. Mandatory HIV testing of sex workers may drive some sex workers underground for fear of losing their livelihood. Hence, it is useful to consider regulation in its broadest sense to best understand governmental efforts to control sex and sexuality.

A challenge to assessing regulation of sex and sexuality across countries is the differences in how these issues are presented in national and international legal and policy frameworks. At national level, sexual behaviours are generally regulated while international legal and policy frameworks, and associated reporting mechanisms, tend to focus on population groups, often termed “vulnerable populations”, such as men who have sex with men and sex workers, rather than behaviours.

This article focuses on regulation of sex between men and sex work because of the ways in which they highlight current debates on and the evolving nature of regulation, and because quantitative and qualitative self-reported government data for 2008 are publicly available for them. We begin with an overview of relevant international legal standards and briefly summarize the HIV-related impacts of laws and policies in these areas, highlighting some of the work that has been done to date around their documentation. We then present an analysis of the self-reported data of 133 governments concerning men who have sex with men and sex workers in the context of HIV, and discuss the implications of the findings.

The legal basis for assessing government regulation of sex and sexuality

The evolution of the ways sex between men and sex work are covered under international human rights law is a useful marker for judging the progression of international consensus on sensitive topics. The evolution of international human rights law takes place through a wide variety of mechanisms. Most relevant to this discussion is the work of the UN Treaty Monitoring Bodies, each composed of independent experts nominated and elected by national governments in consultation with a wide range of specialized agencies, NGOs, academics and other human rights experts.

While the independent experts on these committees represent many different political and legal ideologies, reaching consensus amongst a relatively small group of people can be achieved fairly quickly as compared to similar advances at the national level. This can in large part be attributed to the complexity of effecting legal reform at the national level, but some governments, including those that have ratified the relevant human rights instruments, also remain reluctant to make changes that run counter to their political ideologies.

Despite these limitations, international human rights law affords insight into how responsibilities for regulating sex and sexuality are understood at global level, and provides the overarching framework within which national laws and policies should be situated. It can therefore act as a check if national laws do not conform to international consensus.

With an emphasis on non-discrimination and the equality of all human beings, the focus of international human rights law is on promoting and protecting the rights of individuals and populations “without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status”.Citation4

Importantly, the language of “other status” is flexible and has grown over time, now encompassing, for example, HIV status and disability. Prior to 1994, sexual orientation was not in any way recognised as a protected “other status” under international human rights law but with the advent of the AIDS epidemic, the Human Rights Committee (the expert group that monitors implementation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights) explicitly rejected the criminalisation of consensual sex between adult males in Australia, stating in the Toonen case that the “…criminalization of homosexual practices cannot be considered a reasonable means or proportionate measure to achieve the aim of preventing the spread of HIV/AIDS.” Citation5

Focusing on people rather than their behaviour, international standards have gradually increased protections for men who have sex with men in a number of ways. In 2000, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights recognised discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation as unacceptable with respect both to the underlying determinants of health and access to health services.Citation6 More recently, the proscription of discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation has broadened to include gender identity, including with respect to the availability of health information and services.Citation7

While these international pronouncements may seem distant from national realities, it is worth noting both the change to the Australian law after the Toonen caseCitation5 and the recent Delhi High Court judgement, which recognised the criminalisation of consensual sexual acts between adults in private as inappropriate – because it was wrong to exclude or ostracise on the grounds of difference, and also because it was seen to drive people underground, making it harder to reach them with HIV prevention, treatment and care services.Citation8

These have been important advances with respect to international norms around sexual orientation, but the same can not be said for sex work. Many of the rights specifically elaborated in the treaties have been found relevant to the lives of sex workers but recognition of sex work under “other status” within international human rights law is not likely to occur anytime soon.Citation9 The focus of international legal discourse has primarily been on keeping people out of sex work and condemning sexual exploitation, with insufficient attention to sex workers' rights once they are so engaged.Citation10–12 Moreover, attention to sex work within the international human rights community has largely focused on women, with little attention to men and transgender people engaged in sex work.Citation13 Perhaps most damaging has been the persistent lack of a clear distinction between sex work and sex trafficking. The 1949 Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Persons and of the Exploitation of the Prostitution of Others is still in existence, premised on a model that works against the rights and health of people already engaged in sex work.Citation14

Organisations of sex workers are currently pushing for increased human rights protections, and UNAIDS and its partners have drawn attention to the dearth of protections for those engaged in sex work.Citation13Citation15 Nonetheless, limited explicit support can be derived from international bodies. Thus, while human rights law is providing increased normative guidance with respect to sexual orientation, this is not yet the case for sex work.

Impacts and documentation efforts

A variety of organisations, primarily non-governmental, have worked to document government regulation of sex between men and sex work, with particular emphasis on their negative impacts. The assessment of these laws and policies has generally focused on their existence, with less attention to the specificity of their content and implementation, and rare attention to the ways in which they co-exist with other legislation that may be relevant to the affected population. Moreover, most of these efforts have focused on regulatory repression and their detrimental effects on health and in relation to HIV. Less attention has been accorded to protective regulatory measures and their positive impacts on access to health and other services. Below we provide details of selected efforts to document the impacts of laws and policies on sexual activity between men and on sex work.

Sexual activity between men

There have been a number of efforts by academics, donor governments, and international organisations to map national laws that regulate sexual activity between men. For example, a study commissioned by UNAIDS categorizes national legal systems in 153 low- and middle-income countries as repressive (80 countries), neutral (46 countries) or protective (27 countries) with respect to sexual diversity.Citation16 Another recent publication finds that homosexuality is illegal in over 80 countries worldwide, with penalties ranging from (unspecified) fines to death.Citation17 Because HIV is the framework under which much of this work has been done, limited attention has been given to women who have sex with women in both the data collected and the resulting policy discussions.

Laws and policies that prohibit discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation have been found to help promote access to HIV-related information and services for men engaged in same-sex sexual activity.Citation16 Conversely, laws that criminalise sexual activity between men, and policies, whether official or not, which permit police and other authorities to harass and assault men who have sex with men with impunity are not only discriminatory but known to impede HIV prevention and treatment programmes.Citation16Citation18 Some of the HIV-related impacts of criminalising sexual activity between men include the proscription of condom distribution within prisons, the lack of HIV prevention information targeting men who have sex with men, and reduced service utilisation due to fear of the potential social and legal repercussions of seeking HIV testing or treatment services.

Sex work

More than 60 countries are known to criminalise the selling of sex and a handful of others to criminalise the purchase of sex.Citation19 Systematic collection of these data at a global level remains to be developed. Nonetheless, according to UNAIDS, in some places the regulation of sex work has focused on the promotion of a safe working environment, including protection from violence, and access to condoms and health services.Citation13

There is evidence to show that even if sexual and reproductive health and HIV-related services are made available to sex workers, in places where sex work is criminalised they are likely not to be used for fear that the person's name, HIV status or other personal information will be made available to the police or other authorities.Citation9 Where sex work is illegal, HIV prevention information may not be made available to sex workers e.g. in a recent survey in Pakistan where sex work is illegal, two-thirds of people selling sex had not heard of HIV.Citation20 Sex workers the world over routinely face violence from their clients as well as the police, and are rarely able to use the legal system to their benefit. Even when a country has an HIV policy in place to ensure equal access to information and services, possession of a condom may nonetheless be used by police as “proof” that a person is a sex worker such as in Kenya.Citation9

Self-reported data for 2008 from 133 countries

Ever more documents are being produced concerning the limitations and harms caused by national legal frameworks, but this information is difficult to collect systematically without government engagement. Consequently, the information available globally tends to be piecemeal at best. Furthermore, governments' appreciation of the public health impacts of such regulation has remained limited despite the documentation provided by non-governmental organisations.

Publicly available information on what governments themselves are saying about their national legal frameworks can offer a window for them to look at their own strengths and limitations in relation to others, and can be used by civil society as the basis for advocacy for legal reform. In this respect, the biennial reports submitted by national governments to UNAIDS provide useful information. Based on commitments outlined in the 2001 Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS that came out of the 2001 UN General Assembly Special Session on AIDS (UNGASS), these reports include quantitative and qualitative data relating to national legal and policy environments.Citation21Citation22 In 2008, 135 countries submitted such reports, two of which did not submit data on their legal and policy environment.

These reports contain responses to a set of questions that encapsulate the core components of a rights-based approach to HIV and focus on the legal and policy environment, the availability of HIV-related services, and national regulation relating to “vulnerable populations,” including men who have sex with men and sex workers.Citation22 All questions require yes/no answers; some also allow explanatory comments. Answers to these questions are compiled by a variety of stakeholders, including non-governmental organisations, people living with HIV, national human rights commissions, UN agencies and private sector representatives. The participation of all of these sectors is designed to capture the collaborative nature of national responses to HIV and to engender a shared understanding of the status of the national epidemic and where work might be strengthened. While encompassing civil society input, all reports are nonetheless approved and submitted by the government, and as such constitute unprecedented self-reported data that are globally comparable, albeit limited to the context of HIV.

As with all self-reported data, the opportunity exists for desirability bias in responses and appropriate caution is required in their interpretation. Yet even as gaps exist, these data are useful precisely because they are self-reported by governments and can be compared both across countries and regions as well as over time.

Analysis of data reported in 2008 reveals that, despite global recognition of the need for a supportive legal and policy environment to ensure an effective HIV response, there are a high number of laws, policies and regulations reported regarding sex between men and sex work that constitute barriers to effective HIV prevention, treatment, care and support. Of particular note is that, even with significant regional variation, 63% of countries report laws, policies or regulations that present obstacles – some blatant, others more subtle – to their ability to deliver effective HIV prevention, treatment, care and support for “vulnerable sub-populations”.Citation23

Below we provide a brief global overview of government regulation in each topical area, mention regional trends and then highlight significant self-reported national regulations. The overview draws attention to trends in supportive laws and policies around sex between men and sex work in the context of HIV followed by reported legal and policy obstacles in each area. We then draw attention to conflicts within national legal frameworks, highlighted by these data, shedding light on areas in need of further investigation.

Sexual activity between men

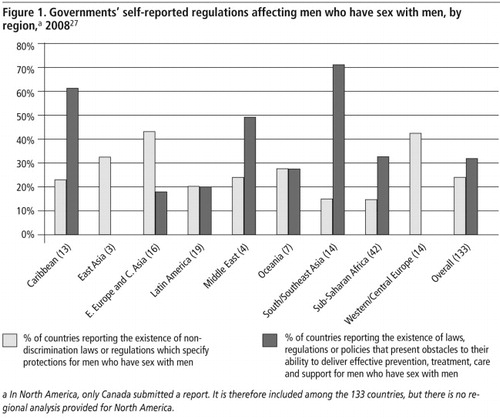

The existence of non-discrimination laws or regulations that specify protections for men who have sex with men is reported by 33 of the 133 countries (25%) (

). Of these, very few were in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia or Southeast Asia.Citation24To better understand the value of the protections reported, consideration of their content is imperative. As one example, Finland's reported protection is a law against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation.Citation25 New Zealand, on the other hand, reported the decriminalisation of homosexual acts between consenting adults.Citation26 Finland's law aims to ensure non-discrimination, while New Zealand's goes further, specifically aimed at creating a supportive environment. Thus, attention to the variability in the support conferred by different laws, even under the same name, is needed.

For what may be very different reasons, no countries in East Asia or Western/Central Europe reported discriminatory laws or policies on sex between men. In contrast, 43 countries (32%) reported having laws that criminalise sex between men in some form (). 71% of countries in South and Southeast Asia report such laws, as do 33% of sub-Saharan African countries. These laws present obstacles to countries' ability to provide effective HIV prevention, treatment, care and support for men who have sex with men (MSM).Citation24 Some of these negative consequences were openly acknowledged by the very governments who have such legislation in place: Citation27

“In the law, there is no recognition of MSM as a group that is discriminated against. There are criminal codes against anal sex. This criminalisation of anal sex negatively affects women, young people, MSM and sex workers.” (Mauritius)Citation28

“Criminalization of MSM… has led this group to go into hiding and thus they do not have access to adequate information and services related to HIV and AIDS. There are laws/policies that could impede MSM's access to services… The high social stigma and discrimination against MSM… in society has at times resulted in violence being meted on group members… MSM should be legally recognized to reduce the stigma and discrimination and to make it easier for members to have access to services.” (Kenya)Citation29

Sex work

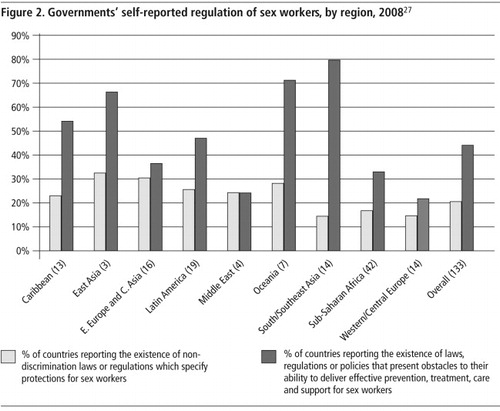

Only 21% of countries reported having in place non-discrimination laws or regulations which specify protections for sex workers (

). Particularly few countries in South and Southeast Asia (14%), Western and Central Europe (14%) and sub-Saharan Africa (17%) reported such protections.Citation24Conversely, 59 countries (44%) reported having laws and policies in place that criminalise sex work and therefore present obstacles to their ability to provide effective HIV prevention, treatment, care and support for sex workers (). An exceptionally high percentage of countries in South and Southeast Asia reported the existence of such laws against sex work (79%).Citation24

In some country reports, it was not the existence of discriminatory laws but the absence of specific protections for sex workers that was noted as an obstacle, for example:

“Supreme Court of Nepal has interpreted sex work as a profession and there is no specific law that penalize sex work in Nepal. However, in the absence of special protection to sex workers, a law dealing with public order and obscenity is used by police time and again to arrest, harass and prosecute sex workers. This harassment discourages sex workers to seek HIV prevention and care programs and therefore is an obstacle in HIV prevention and care.” (Nepal)Citation31

“Since sex work is illegal in Swaziland, this group is usually not easy to identify as they fear being arrested or stigmatized… Several factors are believed to heighten sex workers' vulnerability to HIV. In Swaziland, sex work is highly stigmatized and sex workers are often subjected to blame, labelling, disapproval and discriminatory treatment. This is further worsened by the fact that sex work is illegal and considered a criminal act in the country. In such a situation, it is likely that sex workers may not have easy access to condoms, HIV prevention information and sexual health services.” (Swaziland)Citation32

“Sex work is illegal and therefore used as an excuse to deny services to sex workers.” (St Lucia)Citation33

“In the Penal Code and Penal Procedures, protective measures are restricted to people who do not represent a social threat, and the practice of sex work is considered a social threat. The health code requires sex workers to undergo a sexual health check which is not designed to be holistic care but the fulfilment of a requirement that often generates no benefit and instead promotes or creates police abuse and extortion.” (Guatemala)Citation34

“Sex outside marriage is outlawed and adultery is again punishable by death; however proving adultery is very complicated… There is no specific law against sex work.” (Islamic Republic of Iran)Citation35

“The vagrancy act restricts [HIV] interventions targeting the both male and female sex workers… Police raids brothel and produce the sex workers to courts and for medical check up for STIs.” (Sri Lanka)Citation36

The degree of protection for men who have sex with men and sex workers conferred by reported national legal and regulatory frameworks varies widely between countries. In some places, reported protections focus only on discrimination by third parties, while in others this commitment encompasses the provision of resources to ensure the availability of HIV services to these populations. The extent to which reported laws, policies and regulations constitute barriers to the effective provision of HIV-related services also varies greatly.

Recognised conflicts in laws and policies

Conflict between different laws and policies exists within many national legal frameworks. Emerging evidence, coupled with changing political ideologies, shapes new laws and policies but even as new legislation is put in place, inconsistencies with existing laws and policies are often overlooked. This is particularly true where sensitive issues collide, such as is the case with sexuality and HIV. Thus, policies driven by conservative moral ideologies might seek to regulate sex between men or sex work even as public health policies, driven by epidemiological evidence, aim to make services available to the same people.

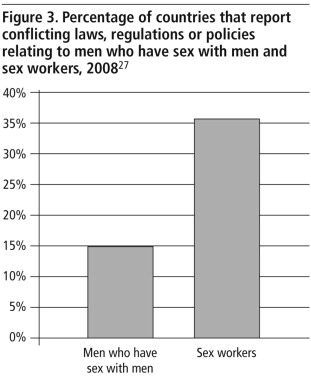

Through the UNGASS process, many countries reported the co-existence of laws or regulations specifying protections for particular sub-populations alongside those that present obstacles to their ability to deliver effective HIV services for these same populations (

).For example, Viet Nam reported that although the HIV law encourages the provision of condoms to vulnerable groups, under other legislation carrying condoms can be regarded as evidence of sex work, which is illegal.Citation37 Similarly, in Turkey, condoms are distributed to men who have sex with men for HIV prevention, but the police regard condoms as evidence of the crime of sex work.Citation38

None of the country reports note whether governments plan to resolve the discrepancies they describe, but the high level of recognition of incompatible laws and policies suggests that advocacy for law reform might go forward. Legal reform is a lengthy process and often politically complex, but the potential positive impacts are significant. Of note, Botswana reported that:

“The mid-term review of the [National Strategic Framework] raised discussion over the need for the national response to HIV/AIDS to address needs of displaced populations, prisoners, sex workers and MSM and recommendations were made to that effect. This is a positive development because it is viewed as setting the tone for a possible review of legislation that outlaws practices such as men having sex with men (MSM) and commercial sex, thus, improves service delivery to them.” Citation39

Regulating populations vs. behaviours

As noted earlier, a major difficulty inherent in assessing the regulation of sex and sexuality is the conflation in policy of language relating to behaviours vs. populations. The international legal framework appropriately prohibits discrimination on the basis of real or perceived membership of a population group against whom discrimination often takes place. The overarching concept of “vulnerable populations” favoured by international mechanisms raises important questions about identity and actions as it is not membership in a population per se that shapes an individual's HIV-related vulnerability, but rather engagement in certain acts or behaviours. For example, although the risk of HIV transmission is greater in anal sex than vaginal sex, this is only true in the absence of correct and consistent condom use. Implicit in the naming of men who have sex with men as a “vulnerable population” is that they are less likely to use condoms than people engaging in heterosexual sex (whether vaginal or anal). In contrast, national legal and policy frameworks seek to regulate specific behaviours even as this may ultimately discriminate against specific populations.

There are a number of reasons to think that the concept of “vulnerable populations”, at least in the context of HIV, has developed as far as it can without significant rethinking. In the 2008 UNGASS reporting round, the list of “vulnerable populations” included: women, young people, injecting drug users, sex workers, men who have sex with men, prison inmates and migrant/mobile populations.Citation22 The conclusion to draw is that the only “non-vulnerable population” in relation to HIV is exclusively-heterosexual adult men who do not inject drugs, engage in sex work and are not imprisoned or mobile/migrants. This mix of demographic characteristics, behaviours and living situations threatens to create increasing confusion regarding how notions of vulnerability are constructed within and across societies. The utility of the notion of “vulnerable populations” for directing the HIV response in the future is thus questionable.

Conclusions

The importance of a supportive regulatory environment for the expression of sexuality is beyond question. It is on these grounds that the WHO and UNAIDS both support the decriminalisation of sex between men and sex work.Citation13Citation40 The 2008 UNGASS country reports constitute the first dataset with global information on how nation states understand their own regulatory frameworks relevant to sex and sexuality, measured against international standards. Even as human rights protections continue to develop, proven public health standards regarding condom use and the promotion of safer sex highlight the need for legal frameworks which not only ameliorate the conditions that make men who have sex with men, sex workers and other populations particularly vulnerable to HIV infection, but also facilitate their use of needed services. The international human rights framework is evolving to encompass new protections, but inconsistencies exist between national laws and international standards and between different policies at national level, which are being rectified at a much slower pace.

The regulation of sex and sexuality remains highly political. There is a continued need for advocacy for legal and policy environments that foster the safe and healthy development and expression of sexuality. Additionally, however, using HIV as an entry point, significant improvements in regulatory frameworks could be implemented that can yield important benefits for men who have sex with men and sex workers. Contextualising the issues raised through the UNGASS reports may help focus national-level legal and policy reform and ensure consonance between international commitments, the national environment and the lived realities of people on the ground. This can ultimately serve to improve access to HIV-related and other services and, critically, to foster the free and safe expression of sexuality.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Riley Steiner's superior research assistance and the collaboration with UNAIDS from which this work is drawn.

References

- A Miller. Sexuality and human rights: discussion paper. 2009; International Council on Human Rights Policy: Versoix.

- S Saunders. Prohibiting sex work projects, restricting women's rights: the international impact of the 2003 US Global AIDS Act. Health and Human Rights. 7(2): 2004; 179–192.

- A Miller. Sexuality, violence against women, and human rights: women make demands and ladies get protection. Health and Human Rights. 7(2): 2004; 17–47.

- United Nations. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. G.A. Res. 217A (III), UN GAOR, Res. 71, UN Doc. A/810. 1948; UN: New York.

- United Nations. Nicholas Toonen v. Australia, UN GAOR, Hum Rts Cte, 15th Sess, Case 488/1992, UN Doc CCPR/c/D/488/1992, 1994.

- UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. General Comment 14 on the right to the highest attainable standard of health. 8 November 2000. E/C.12/2000/4, twenty-second session Geneva, 2000.

- UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. General Comment 20 on non-discrimination in economic, social and cultural rights. 2 July 2009. E/C.12/GC/20. forty-second session Geneva, 2009.

- Delhi High Court. Judgment 7455/2001. 2 July 2009. At: <www.ilga.org/news-upload/Delhi_high_court_decision.pdf. >. Accessed 26 October 2009.

- Federation of Women Lawyers Kenya. Documenting human rights violations of sex workers in Kenya. 2008. At: <www.soros.org/initiatives/health/focus/sharp/articles_publications/publications/fida_20081201. >. Accessed 26 October 2009.

- United Nations. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, GA Res. 34/180, UN GAOR, 34th Sess, Supp. No. 46, at 193, UN Doc. A/34/46. 1979; UN: New York.

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), GA Res. 44/25, UN GAOR, 44th Sess, Supp. No. 49, at 166, UN Doc. A/44/25. 1989; UN: New York.

- United Nations. Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography. GA Res. 54/263, Annex I, 54 UNGAOR, Supp. No. 49, at 7, UN Doc. A/54/49/. 2000; UN: New York.

- UNAIDS. Guidance note on HIV and sex work. 2009; UNAIDS: Geneva. At: <http://data.unaids.org/pub/BaseDocument/2009/jc1696_guidance_note_hiv_and_sexwork_en.pdf. >. Accessed 26 October 2009.

- United Nations. Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Persons and of the Exploitation of the Prostitution of Others. 2 December 1949, A/RES/317. At: <http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/trafficpersons.htm. >. Accessed 26 October 2009.

- A Crago. Our Lives Matter: Sex Workers Unite for Health and Rights. 2008; Open Society Institute: New York. At: <www.soros.org/initiatives/health/focus/sharp/articles_publications/publications/ourlivesmatter_20080724. >. Accessed 26 October 2009.

- C Caceres, M Pecheny, T Frasca. Review of legal frameworks and the situation of human rights related to sexual diversity in low and middle income countries. Study commissioned by UNAIDS, 2008. At: <www.clam.org.br/publique/media/vozescontra377.pdf. >. Accessed 26 October 2009.

- S Long, AW Brown, G Cooper. More than a Name: State-sponsored Homophobia and its Consequences in Southern Africa. 2003; Human Rights Watch: New York.

- A Smith, P Tapsoba, N Pershu. Men who have sex with men and HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet. 374: 2009; 416–422.

- D Kulick. On the “Swedish Model.” Global Rights. At: <http://www.globalrights.org/site/DocServer/Don_Kulick_on_the_Swedish_Model.pdf?docID=5803. >. Accessed 26 October 2009.

- S Hawkes, M Collumbien, L Platt. HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among men, transgenders and women selling sex in two cities in Pakistan: a cross-sectional prevalence survey. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 85(Suppl 2): 2009; ii8–ii16.

- UN General Assembly Special Session on HIV/AIDS. Declaration of commitment on HIV/AIDS. 2001; UNAIDS: Geneva. At: <www.un.org/ga/aids/coverage/FinalDeclarationHIVAIDS.html. >. Accessed 26 October 2009.

- UNAIDS. Monitoring the declaration of commitment on HIV/AIDS: guidelines on the construction of core indicators. 2007; UNAIDS: Geneva. At: <http://data.unaids.org/pub/Manual/2007/20070411_ungass_core_indicators_manual_en.pdf. >. Accessed 26 October 2009.

- United Nations. Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS and Political Declaration on HIV/AIDS: Midway to the Millennium Development Goals Report of the Secretary-General. April 2008. At: <www.ua2010.org/en/content/download/26157/309352/file/SG%20Report_UNGASS.doc. >. Accessed 26 October 2009.

- UNAIDS. UNGASS progress reports submitted by countries. 2008. At: <www.unaids.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/HIVData/CountryProgress/2007CountryProgressAllCountries.asp. >. Accessed 26 October 2009.

- UNAIDS. UNGASS progress reports: Finland. 2008. At: <http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2008/finland_2008_country_progress_report_en.pdf. >. Accessed 26 October 2009.

- UNAIDS. UNGASS progress reports: New Zealand. 2008. At: <http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2007/new_zealand_2008_country_progress_report_en.pdf. >. Accessed 26 October 2009.

- Adapted from: Gruskin S, Ferguson L, Peersman G, Rugg D. Human rights in the global response to HIV: findings from the 2008 UNGASS reports. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (accepted for publication, in press 2009).

- UNAIDS. UNGASS progress reports: Mauritius. 2008. At: <http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2008/mauritius_2008_country_progress_report_en.pdf. >. Accessed 26 October 2009.

- UNAIDS. UNGASS progress reports: Kenya. 2008. At: <http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2008/kenya_2008_ncpi_en.pdf. >. Accessed 26 October 2009.

- UNAIDS. UNGASS progress reports: Zimbabwe. 2008. At: <http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2008/zimbabwe_2008_country_progress_report_en.pdf. >. Accessed 26 October 2009.

- UNAIDS. UNGASS progress reports: Nepal. 2008. At: <http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2008/nepal_2008_country_progress_report_en.pdf. >. Accessed 26 October 2009.

- UNAIDS. UNGASS progress reports: Swaziland. 2008. At: <http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2008/swaziland_2008_country_progress_report_en.pdf. >. Accessed 25 August 2009.

- UNAIDS. UNGASS progress reports: Saint Lucia. 2008. At: <http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2008/saint_lucia_2008_country_progress_report_en.pdf. >. Accessed 26 October 2009.

- UNAIDS. UNGASS progress reports: Guatemala. 2008. At: <http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2008/guatemala_2008_country_progress_report_sp_es.pdf. >. Accessed 26 October 2009.

- UNAIDS. UNGASS progress reports: Islamic Republic of Iran. 2008. At: <http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2008/iran_2008_country_progress_report_pe_xx.pdf. >. Accessed 26 October 2009.

- UNAIDS. UNGASS progress reports: Sri Lanka. 2008. At: <http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2008/sri_lanka_2008_country_progress_report_en.pdf. >. Accessed 26 October 2009.

- UNAIDS. UNGASS progress reports: Vietnam. 2008. At: <http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2008/viet_nam_2008_country_progress_report_en.pdf. >. Accessed 26 October 2009.

- UNAIDS. UNGASS progress reports: Turkey. 2008. At: <http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2008/turkey_2008_country_progress_report_en.pdf. >. Accessed 26 October 2009.

- UNAIDS. UNGASS progress reports: Botswana. 2008. At: <http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2008/botswana_2008_country_progress_report_en.pdf. >. Accessed 26 October 2009.

- UNAIDS. Action framework: Universal access for men who have sex with men and transgender people. 2009. At: <http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2009/jc1720_action_framework_msm_en.pdf. >. Accessed 26 October 2009.