The papers in this journal issue are about the law and criminalisation relating to rape and sexual violence, female genital mutilation (FGM), selling and buying sex, provision and use of modern contraception and induced abortion, homosexuality, and HIV transmission and exposure. The papers are highly thought-provoking, especially when read together, not least because the question of whether criminalisation is a good thing or a bad thing must be answered quite, quite differently in relation to each criminalised practice explored. It is easy to argue why modern contraception and induced abortion should be legal because they are necessary to protect women's lives and health, and that sexual identity is inherent in the person and must be respected by society and protected in law. It is not so easy to determine how justice should be best served, as opposed to exacting retribution or revenge, or how to protect the rights of both perpetrators and victims, when a serious or life-threatening harm has been done, including and even in the absence of criminal intent to harm, as with HIV transmission and exposure.

Laws expressing moral condemnation

The many laws analysed in these papers tend to be used infrequently, often arbitrarily and against people without easy access to legal representation. There are obviously not enough police, lawyers, judges or prisons to take on everyone who is criminalised under such laws. However, some laws serve as a statement of opprobrium and moral condemnation in response to a behaviour that is considered wrong, and they can serve this purpose without anyone necessarily being put into jail, or only a few people intermittently as a reminder that they are there. Thus, where abortion is legally restricted, women who seek an abortion may not be prosecuted but they may not have recourse to safe abortion either, and the intended punitive purpose is served to a greater or lesser extent.

In order to repeal such laws, a critical mass of citizens needs to be or become convinced that the practice in question is acceptable and legitimate and deserves to be decriminalised, and active campaigns to change the law need to be carried out. This happened with modern contraception during the first half of the 20th century in most countries. However, even when public attitudes have become more supportive, as with induced abortion in a growing number of countries, the fear that law reform will activate residual and sometimes powerful opposition may deter or delay reform, sometimes for decades. Belton et al show most powerfully how an Indonesian law criminalising abortion, still in force in now-independent Timor Leste, was reformed to allow abortion to save the woman's life and health as part the revised Penal Code 2009, and then abruptly reversed only a month later in a context of heavy Catholic church influence. Casas and Ahumada too show how the universal provision of sexuality education in Chile, even under supportive governments, has been blocked for many years because of right-wing and Catholic influence. Similarly, Lee et al show in the Philippines that in spite of very high levels of public support for contraceptive use, Catholic influence has supported local political leaders to pass local ordinances banning state provision of modern contraception, in spite of its legality nationally. Another paper by Casas analyses the use of conscientious objection to providing legal health services, such as contraception, emergency contraception and legal abortion, by physicians in Chile, Mexico and Peru. Although this is not about criminalisation per se, it is about how some physicians are abusing their own right to object in order to sabotage the rights of those needing these services, so as to prevent them from receiving them, which can have the same effect as criminalising the services by making them inaccessible. The Catholic church under the current Pope has made itself a formidable enemy of sexual and reproductive rights.

The media play an equally important role, since they give publicity to cases that do come to court, and act as a moral compass and a mirror of public reaction, for good or otherwise. They can be a crucial support to progressive law reform but they can also make it nigh on impossible to change a discriminatory and harmful law by twisting a public health purpose into a contentious moral issue about illicit sex. The tabloid press in particular, owned and run mostly by powerful conservative forces, thrives on demonising and sensationalising anything to do with sex and sexuality, and can greatly contribute to a climate in which people who have done no harm to anyone may be harassed, prosecuted and even murdered.

Laws aimed at preventing harm to health and life

All the papers on criminalisation of HIV transmission published here are totally opposed to such criminalisation, and contain a myriad of good reasons why. See especially the 10 reasons document and the report of the UNAIDs/UNDP conference, reprinted here. Yet research has shown that many people (including people with HIV) believe that punishment can be an appropriate response when someone has infected another person. Unfortunately, none of these papers answers the question of why so many thinking people have supported laws criminalising HIV transmission, or what has led to these laws being passed 30 years into the AIDS epidemic. Nor did anyone look at these laws in the context of the history of laws and policies aimed at curbing other epidemics, such as syphilis in the 19th century. Many of the laws criminalising HIV transmission were aimed at and also contain clauses about protecting the rights of HIV-positive people, as the paper by Sanon et al shows regarding Burkina Faso's law. It would be helpful to understand the reasoning behind this dual purpose as it could shed crucial light on current perceptions about HIV transmission and what to do about it, apart from being opposed to its criminalisation.

The decline in and apparent failure of HIV prevention efforts must surely be an important reason why these laws are proliferating, alongside the continuing stigma of having HIV. Until effective and comprehensive HIV prevention policy is put back onto national and international agendas with sufficient resources and priority, and begins to have an effect, I believe recourse to such laws will continue — precisely because they are a way to express condemnation, albeit ineffectually and even adversely, of the continuing spread of infection.

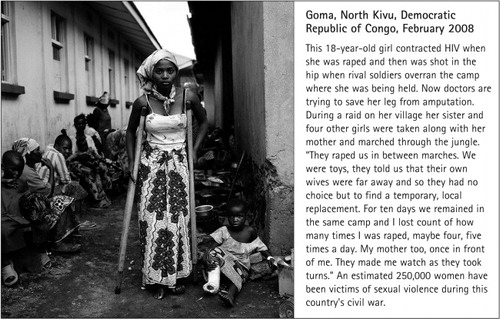

Another, compelling reason for these laws emerges in the paper by Kilonzo et al on sexual violence and criminal justice in sub-Saharan Africa, and is discussed also by Brown et al. There is a close connection between widespread rape and sexual violence in conflict and crisis settings and the spread of HIV infection where HIV prevalence is high. In these settings, HIV infection is only one in a long list of harms experienced by women who have been violated (see, for example, the photograph in this editorial). This reason for criminalising HIV transmission is based in the demand for justice and retribution. There is no escaping the fact of the multiple egregious harms being inflicted on women and children, with total impunity, in these settings. That the criminal law exists at all is due to the intent to do harm. The question of how justice can be served in the exercise of the criminal law in this context is incredibly complex but the need for it cannot be brushed aside with platitudes. As Kilonzo et al show, there are no comprehensive post-rape care services, nor is there the requisite co-ordination between HIV and sexual and reproductive health services, and the legal and judicial systems, to implement sexual violence legislation effectively.

Certainly, no society takes rape and sexual violence seriously enough to stop it happening. The best that has been achieved to date, no matter how “developed” the country, is that the health system provides treatment, care and support for at least a few of the victims and the criminal justice system puts a handful of perpetrators away each year. Nothing more.

Hence, while there may be no question that criminal prosecution is not the way to stop HIV transmission from taking place, there remains a locus of responsibility which must be addressed. Whether or not there is intent in the legal sense to transmit HIV, the outcome of transmission is a serious harm and more so where treatment is not available. In a world where upwards of one in four young women experiences pressure or coercion to have sex as their first sexual experience, do activists really think that the defence of “we were just having sex” or “I didn't know” or “I didn't mean to infect her/him ” is sufficient? After millions of deaths from AIDS, HIV is still raging its way through people's bodies and lives, and is swallowing up unprecedented levels of resources. Even so, only an estimated 30% of the people with HIV in developing countries have access to treatment, and they are only getting treatment when they have severe, symptomatic infection.Citation1 We cannot afford to let this go on indefinitely, and it is hard to understand why anyone thinks that 100% access to treatment on its own is the answer. Whatever happened to Noerine Kaleeba's call for people not to let the virus leave their bodies until they die?Citation2 What other means exist for putting pressure on people not to transmit the virus — or in the case of those who are untested, to stop putting themselves and possibly others at risk?

Female genital mutilation is a harmful traditional practice and it has been criminalised in many countries as one means of trying to stop it happening. Unprotected sex is also a harmful traditional practice, and needs to be classified as such as a critical part of our understanding of public health and human rights. When will activists stop making excuses for it?

Laws that seek both to condemn and protect

And then there is the subject of criminalisation or decriminalisation of prostitution, or sex work, or buying and selling sex, or trafficking in women and children — call it what you will. This remains the most vexed issue of all because these laws are about both the expression of moral condemnation and the intention of preventing harm to health and life. How to resolve the fact that there are two equally compelling sets of feminist arguments, in apparent conflict with each other, for and against criminalisation, represented here by Strøm on the one hand and Lutnick and Cohan on the other. Disentangling questions of who is being harmed and who is doing harm, and how to prevent harm in the sub-cultures of commercial sex, is work in progress and will be so for many years to come. Here are some of the questions these two papers raise for me:

Will the appallingly high levels of exploitation, violence, degradation and abuse experienced by so many of those selling sex really be eliminated through legalisation or decriminalisation? We know that the repeal of other discriminatory laws does not mean that violence, prosecution and harassment will stop, e.g. with laws decriminalising homosexuality or those making abortion legal.

How can normalising the buying and selling of sex be squared with the feminist principle of a person’s right of autonomy over their own body? This cannot be discussed in relation to sex workers only; it also involves knowing far more about the kinds of sexual “need” that motivate (mostly) men to buy sex and to seek sex with children. Should these “needs” be tolerated and accepted or not? Should they be discussed with adolescents in sex education classes, or not?

If so many women are really willing to sell sex, why do so many require the crutch of alcohol and drugs to get them through each day?

How can the association between sexual abuse in childhood and sexually abused adults selling sex be broken?

Consequences, unintended effects and inadequacies of these laws

Will lots of people be prosecuted just because a new criminal law is placed on the statute books? This is not a given. What we fear might happen and what is happening or will happen when laws such as those against HIV transmission are passed may not be the same thing. Csete et al call for mother-to-child transmission of HIV to be explicitly excluded from such laws but they recognise that almost no prosecutions of mother-to-child transmission of HIV have materialised, even though many HIV criminalisation laws are broad enough to enable such prosecutions and only a few laws have been sensitive to the dangers and have therefore excluded vertical transmission.

The very arbitrariness in the prosecution of such laws may strike fear in some hearts and create a desire to avoid doing something deemed to be wrong, thus at least to some extent preventing harm where the aim is to protect against harm. Nevertheless, as Dodds et al show with criminalisation of HIV transmission, while behaviour may well be affected for the good in many cases, i.e. encouraging the practice of safer sex, it may also have unintended, unwelcome and even adverse effects, not least because people may misunderstand what exactly has been criminalised and whether or not their own behaviour is actually transgressing the law. Moreover, a law may be executed unjustly and in ways never intended by those who passed it. This journal issue is peppered with descriptions of such cases, particularly in the Round Up sections on criminalisation, law and policy, and advocacy. For example, women who report that they have been raped may find themselves in prison in some countries for having committed “adultery” or murdered in an “honour killing”, in which they are seen as having dishonoured their family, while the rapist is untouched.

A law may be so broad, problematic or unclear that no one would try to or succeed in implementing it. As Kilonzo et al show with sexual violence laws in sub-Saharan Africa, the resources and trained investigators to find perpetrators, and the mechanisms needed to collect evidence and take prosecutions forward are just not there.

Similarly, as Aberese Ako and Akweongo show as regards the law criminalising female genital mutilation (FGM) in Ghana, there is so much community complicity in supporting the practice that the police say they are unable to identify anyone to arrest. Yet this is a law that appears to be having a successful influence on public thinking about FGM. Although the practice continues and its extent is unknown, it appears to be on the decline, with more people expressing opposition to it and more saying they will not inflict it on their children. The authors therefore argue that plans to strengthen the law and criminalise not only the “circumciser” (as now) but others in the community who aid and abet the practice is the right route to follow.

What needs to be done

Governments need greater self-awareness of the harms caused by some of the adverse ways in which they regulate and criminalise sexuality, and which laws and policies are beneficial. Every two years, in compliance with the UN Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS adopted in June 2001, states submit country reports to UNAIDS, using an international reporting mechanism to measure their progress in responding to the HIV epidemic. Gruskin and Ferguson studied the responses of 133 countries in 2008 to questions about policies related to men who have sex with men and sex workers in relation to HIV. By identifying dissonance between international human rights and public health standards and actual national laws and policies, a refocusing of national efforts is made more possible. This could obviously be applied more broadly than to HIV. For example, in considering whether to strike down the law that criminalised homosexuality, this kind of analysis took place in the High Court in Delhi in July 2009, described here by Misra. The outcome, in line with international human rights principles against discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation, was that consensual sex between adults of the same sex had to be removed from the criminal law. This is in painful contrast to reports published on the Human Rights Watch website, excerpted and reprinted in the Bookshelf section here, of police harassment, brutality and torture, as well as the arrest and conviction, of men suspected of homosexuality in Egypt.

As Brown et al point out, the human rights movement must ensure that the state does not act outside the constraint of the law and abuse its powers in ways that are discriminatory or capricious, or that have the effect of criminalising a person's status as opposed to an act. The state must also ensure that criminal justice responses do not conflict with health responses, but does the converse also hold true?

Brown et al point out that where a behaviour is criminalised, such as injection drug use, the authorities tend to concentrate on the criminal aspects of the behaviour and often do not ensure that the person gets the health services and therapy they need, e.g. to come off addictive drugs and live without them. Similarly, Lutnick & Cohan quote sex workers saying that one reason why they support the continuing criminalisation of prostitution is this very reason, that jail is the only place that allows them to dry out from time to time. Hence, the interface between the criminal justice system, social services and the health system needs far more attention.

As most of the papers in this journal issue illustrate, country case studies and cross-country comparative studies of different laws, what definitions they are based on, and how they are being understood and implemented in the country context, are crucial to advocacy in support of public health, human rights and justice in our field. Based on such an analysis of laws in the USA that criminalise consensual sexual conduct and eliminate informed consent to HIV testing through mandatory testing policies, the paper by Ahmed et al outlines a set of concrete recommendations for protecting HIV-positive women's rights in the US National HIV/AIDS Strategy called for by President Obama.

A major assumption underlying opposition to laws criminalising certain sexual behaviours is that the behaviours cannot be stopped, e.g. people will always take sexual risks and men have always paid for sex. Are such assumptions actually true or justifiable? There remain many unresolved issues about whether and how harmful behaviour can be changed and how to ensure that bodily autonomy and sexuality are respected at the same time.

Post-abortion care: serious delays in initiation of treatment uncovered

I would like to call special attention to the articles by Mayi-Tsonga et al and Kinaro et al on a previously hidden problem in post-abortion care services in Gabon and Sudan, respectively, as regards access to timely treatment. Both these studies have uncovered serious delays in major hospitals between the time women present for treatment of complications and treatment actually being provided. In the Sudan study, 14.5% of the women had to wait 5—8 hours and 7.3% for 9—12 hours for treatment, and no woman was seen without any delay. In the Gabon study of obstetric deaths from three causes, the mean time between admission and treatment was 1.2 hours in the case of women who died from post-partum haemorrhage or eclampsia but as high as 23.7 hours in the case of women who died from complications of unsafe abortion. Such delays, the authors of the Gabon study conclude, may constitute an important determinant of the risk of death from abortion-related complications.

Short features

Furedi describes a new emergency contraceptive, developed by a small, new pharmaceutical company that is chaired by one of the pioneers who developed mifepristone for medical abortion. If the new method turns out to be worth the price, despite its higher cost, its success will encourage further innovation.

Lastly, did we think that safe birthing centres were an uncontentious issue? Diniz disabuses us in her article about how aggressive resistance from the medical establishment to out-of-hospital birth and autonomous delivery practice by nurse-midwives led to the closure of a birthing centre in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil this year. The centre is one of only a few such centres in Brazil where women can be assured of a trial of labour and a normal delivery instead of a caesarean section or a vaginal delivery made miserable by over-intervention. The immediate response from the women's health movement and others saw the centre re-opened within weeks. Three cheers for the women's health movement.

Prof José A Pinotti: in memoriam

Prof José Pinotti, who died in July 2009 in São Paulo, Brazil, had a distinguished career as an obstetrician-gynaecologist. He was an active member of FIGO for two decades and served as its president in 1988—91. He was considered an outstanding reproductive health clinician and breast cancer surgeon, scientist and academic, and worked with government at different levels in Brazil to develop health policy and medical education. He authored over 400 publications and contributed to many textbooks. His one article in RHM is, in my view, one of the most important we have published; it offers a model of comprehensive health care for women that deserves to be widely read and emulated.Citation3

RHM readers survey

Enclosed with this journal issue is a little readers' survey. We believe it is time for RHM to reconsider how and how well it is contributing to the sexual and reproductive health and rights field and how to do so in future, given the many structural changes taking place in current policy and practice. We would be grateful if you, dear readers, would take the time to answer these questions, and if you have more to say, volunteer to be interviewed further.

RHM website revamped

For the past 18 months, we have been working on revamping the RHM website, a task that makes editing of articles seem easy. This week, the site finally went live! So do check out <www.rhmjournal.org.uk> and let us know how you think we should expand it, which we will start doing in the new year, e.g. in relation to writing and editing skills, news, and creating links to useful materials for work at country level.

References

- N Ford, E Mills, A Calmy. Rationing antiretroviral therapy in Africa – treating too few, too late. NEJM. 360(18): 2009; 1808–1810.

- Kaleeba N, with Ray S and Willmore B. We miss you all; Noerine Kaleeba: AIDS in the family. Harare: Women & AIDS Support Network, 1991.

- JA Pinotti, ML Tojal, AC Nisida. Comprehensive health care for women in a public hospital in São Paulo, Brazil. Reproductive Health Matters. 9(18): 2001; 69–78.