Abstract

In 2008, Scarlet Alliance, the Australian Sex Workers Association, carried out a needs assessment among sex workers living with HIV in Australia. The research showed that HIV positive sex workers experience discrimination from within the community, are criminalised for sex work and subject to disclosure laws in some states and territories, and face stigma perpetrated by the media. Supported by legislation, they have an almost insurmountable lack of access to policy development due to disclosure and confidentiality issues, and have expressed ongoing frustration at the lack of leadership on the intersecting issues of HIV and sex work. A high profile prosecution of a sex worker living with HIV coincided with the duration of the needs assessment project. The research gave a voice to sex workers living with HIV and highlighted the levels of institutionalised marginalisation and stigmatisation they experience. Criminalisation of sex work, of people living with HIV, and of sex workers living with HIV is at the core of this discrimination and must be challenged. Scarlet Alliance advocates for the decriminalisation of sex work across all jurisdictions in Australia. This will deliver rights to sex workers living with HIV and create a more equitable and productive environment for HIV prevention and public health generally.

Résumé

En 2008, Scarlet Alliance, l'Association australienne de professionnel(le)s du sexe, a évalué les besoins des professionnel(le)s du sexe vivant avec le VIH en Australie. La recherche a montré que la communauté exerçait une discrimination à l'égard de ces personnes; dans certains États et territoires, leur travail était criminalisé et elles étaient soumises à des lois sur la révélation du statut ; et elles faisaient face à une stigmatisation véhiculée par les médias. Elles se heurtent à un manque presque insurmontable d'accès à la formulation des politiques, aggravé par la législation, en raison des questions de révélation et de confidentialité, et elles se déclarent frustrées par l'insuffisance du leadership sur les questions touchant à la fois au VIH et au travail sexuel. L'évaluation des besoins a coïncidé avec le procès très médiatisé d'un professionnel du sexe vivant avec le VIH. La recherche a donné une voix aux professionnel(le)s du sexe vivant avec le VIH et a mis en lumière les niveaux de marginalisation et de stigmatisation institutionnalisées que connaît cette catégorie de personnes. La criminalisation du travail sexuel, des séropositifs et des professionnel(le)s du sexe vivant avec le VIH est au cłur de cette discrimination et doit être combattue. Scarlet Alliance préconise la dépénalisation du travail sexuel dans toutes les juridictions australiennes. Cela donnera des droits aux professionnel(le)s du sexe vivant avec le VIH et créera un environnement plus équitable et productif pour la prévention du VIH et la santé publique en général.

Resumen

En 2008, Scarlet Alliance, la Asociación de Trabajadoras Sexuales Australianas, realizó una evaluación de necesidades entre trabajadoras sexuales que viven con VIH en Australia. La investigación mostró que las trabajadoras sexuales VIH positivas son discriminadas en la comunidad y penalizadas por trabajo sexual, están sujetas a leyes de divulgación en algunos estados y territorios, y confrontan estigma perpetrado por los medios de comunicación, el cual es apoyado por la legislación. Su falta de acceso al desarrollo de políticas es casi insuperable debido a cuestiones de divulgación y confidencialidad, y han expresado continua frustración ante la falta de liderazgo en asuntos relacionados con el VIH y el trabajo sexual. Un juicio destacado de una trabajadora sexual que vivía con VIH coincidió con la duración del proyecto de evaluación de necesidades. La investigación dio voz a las trabajadoras sexuales que viven con VIH y destacó los niveles de marginación y estigmatización institucionalizadas que sufren. La penalización del trabajo sexual, de personas que viven con VIH y de trabajadoras sexuales que viven con VIH es el meollo de esta discriminación y se debe cuestionar. Scarlet Alliance aboga por la despenalización del trabajo sexual en todas las jurisdicciones de Australia, lo cual defenderá los derechos de las trabajadoras sexuales que viven con VIH y creará un ambiente más equitativo y más productivo para la prevención del VIH y la salud pública en general.

Australia has the best conditions in the world for sex work, as all its states and territories support some level of decriminalisation of the sex industry, which enables sex workers to negotiate work practices. Australia also has some of the best services and laws for people with HIV – each state and territory offers tailored services and anti-discrimination protections to people with HIV. However, the situation of sex workers with HIV is another issue entirely, as it is characterised by criminalisation, stigma and discrimination, and needs to be better understood. To this end, in 2008, Scarlet Alliance, the Australian Sex Workers Association, carried out a needs assessment among sex workers living with HIV in Australia in order to provide an evidence base for the health and HIV sector providing services for sex workers with HIV in Australia, as well as for policymakers and HIV-positive sex workers themselves. Providing a voice for marginalised communities to influence and create partnerships with government, policymakers and service providers is the day-to-day work of Scarlet Alliance and its membership of sex worker organisations. This paper describes the needs assessment project, how it was carried out, the findings and how the information is being used to lobby for better conditions for HIV-positive sex workers.

Background

Fear and uncertainty have been the typical response to HIV in Australia for many years. From the initial panic in the 1980s, during which gay men, drug injectors and sex workers were all condemned, to the “Grim Reaper” campaign in 1987,Footnote* the public have been conditioned to be scared and suspicious of HIV and AIDS and of the minority groups that are perceived as either “at risk” of HIV or responsible for spreading the disease. The “Grim Reaper” campaign has had a lasting impact on the Australian psyche and popular attitudes towards HIV/AIDS. Along with the association of HIV with traditionally marginal communities, a great amount of stigma was cemented into the mainstream response to HIV and AIDS, which continues to focus on sickness, disease and death. The morality that opposes homosexuality, alternative sexuality or in some cases any sex outside of heterosexual marriage has also been a contributing factor, which labels HIV as dirty and HIV-positive people as deserving of punishment.

One reason why the Australian public still responds to HIV with fear is that the federal government never produced another campaign to update the community on current policies on HIV transmission, prevention and treatment, and community development with affected communities. These have been consistent and have gradually been improving, but they have remained mostly outside of the mainstream line of vision.Citation2 Activities by sex worker organisations, AIDS councils and positive people's organisations have targeted people living with HIV, gay men's communities, sex workers and in recent years, lesbians.Citation3Citation4 However, they too have stayed outside of mainstream vision, and although community organisations have sought funding for mainstream stigma reduction campaigns, none has ever eventuated.Citation5Citation6

HIV-positive sex worker jailed 2008

In 2008, an HIV-positive sex worker was charged and jailed in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) for providing a sexual service while “knowingly infected with HIV” even though no evidence of unsafe behaviour was presented. Under ACT law, the offence is defined as follows:

“A person shall not, at a brothel or elsewhere, provide or receive commercial sexual services if the person knows, or could reasonably be expected to know, that he or she is infected with a sexually transmitted disease. Maximum penalty: 50 penalty units, imprisonment for 6 months or both.”Citation7

As a result of the case and the publicity, many sex workers became fearful of testing for HIV, leading to a dramatic drop in sex worker attendance at an outreach medical service in parlours in Canberra, coordinated by the Sex Workers Outreach Project in ACT with Canberra Sexual Health. In the four-week period following the court case, the numbers attending the service dropped from an average of 40 per night to three.Citation8 These concerns were documented by the Sex Workers Outreach Project and reported to the ACT Attorney-General by Scarlet Alliance, as reported in the Canberra Times:

“ACT Attorney-General Simon Corbell … said the Alliance told him many sex workers had stopped screening for sexually transmitted diseases because they did not want to be prosecuted for knowingly operating with a disease. ‘That's a serious concern, because you don't want to create a situation where sex workers are acting in ignorance of their sexual health status,’ he said. The Alliance wants the Government to remove a section of the Prostitution Act that makes it an offence for sex workers to knowingly infect clients with sexually transmitted diseases. Mr Corbell has ordered his department to investigate whether the prostitution laws needed changing.”Citation9

“The epidemiology in Australia supports our understanding that Australian sex workers are on the whole effectively implementing safe sex practices with their clients on a daily basis. We know that in the majority of cases it is the client that does not perceive themselves to be at risk and the sex worker that successfully negotiates and implements safe sex practices.

What we have learnt from our partnership (between Government and Communities) response to the AIDS epidemic is that when safe sex practices are implemented, including the combination of condoms and water-based lubricant, the risk of transmission or acquiring HIV is very low. And condoms do work, evidenced by the low rates of HIV or STIs amongst sex workers in Australia. But it must be understood that safe sex is a shared responsibility. If unsafe sex has occurred it is the responsibility of both parties.

HIV is transmitted by unsafe sex, not because money changes hands.

The high number of sero-discordant relationships in which the HIV negative partner does not acquire HIV demonstrates that protected sex with an HIV-positive person does not necessarily lead to transmission… The high levels of condom use amongst Australian sex workers means there is no need to exclude HIV positive people from sex work. The cultural norms in the industry are high levels of condom use and very responsible approaches to implementing safe sex by individual sex workers.”Citation10

“There is a vast difference between being sexually active with a sexually transmissible disease and actually infecting someone, whether in a commercial or personal context. This legislation is unable to acknowledge the shared responsibility… or the wide variety of sexual activity that is available posing low or no risk.”Citation11

The needs assessment project

For the research with sex workers living with HIV, Scarlet Alliance developed realistic goals and focused on enabling sex workers with HIV to be in the leadership of the project and ensuring that their voices were heard throughout the process. The research itself and the analysis of the interviews were led, driven, executed, evaluated and presented by sex workers living with HIV. A close relationship was forged between the National Association of People Living with HIV and AIDS (NAPWA) and Scarlet Alliance, which informed the project.

Participants were recruited through a leaflet circulated through our e-mail networks, sex worker projects and peer organisations, AIDS Councils, HIV peer organisations, HIV sector agencies, sexual health clinics and advertisements on internet dating sites accessed by sex workers. There were 13 participants who came forward in total, nine from capital cities and four from outside of capital cities. Interviews were conducted in person and by phone. Interviews took place in a relaxed, conversational style, and explored firstly any self-identified issues or topics raised. Participants were not asked to respond to a question-and-answer style survey but were encouraged to talk about the things that mattered most to them, in their own voices. They were also asked for feedback on a range of issues, including criminalisation and access to services through HIV community services, sexual health clinics, sex worker services, HIV peer-based organisations, medical services and any other relevant services (government or NGO) and any barriers to access; how comfortable they were disclosing dual status of HIV and sex work, and if not why not; and any other associated real or perceived discrimination and harassment.

We had intended to have focus group discussions, but all participants felt more comfortable with one-on-one interviews, either in person or over the phone. The option to conduct focus group discussions on an anonymous e-list was offered to participants but was not taken up. Payment to participants for their time on the project was sent anonymously through a voucher website.

Due to the highly stigmatised and sometimes illegal nature of the activities of HIV-positive sex workers in many parts of Australia, it was important to ensure a level of privacy and confidentiality that met the individuals' particular needs. Recorded interviews and transcripts were destroyed upon completion of the project for this reason. Additional privacy measures were also adopted during the project, at the request of participants, for example the withholding of certain demographic information in the report.

The option of submitting an anonymous written submission was also provided. Participants were not given any documentation that would connect them to Scarlet Alliance, sex work or to HIV. All participants were given the opportunity to withdraw at any time and were informed that contact details and results would be available on the Scarlet Alliance website.

The challenge in developing new and contemporary leadership on the needs of sex workers with HIV in Australia was to allow for confidential and appropriate methods of participation for sex workers with HIV, who know the issues best. To these ends, Scarlet Alliance designed the project to be flexible, and established a steering committee of sex workers living with HIV to inform the project.

Scarlet Alliance has confidence in peer-driven, evidence-based policy. Since the origins of peer-driven and led services for sex workers in Australia, over 20 years ago, collection and analysis of statistics has formed an integral part of the groundwork and the feedback-loop for peer-led service delivery and the Australian Government partners who fund it. Collecting statistics, data, participating in research, collecting anecdotal evidence, creating steering committees, networking, and providing community development opportunities all contribute to making sex worker organisations authentic and strong in Australia.

The intention of the needs assessment was to provide an evidence base for the entire health and HIV sector providing services for sex workers with HIV in Australia. We needed to move people's experiences and knowledge from the anecdotal and personal to the reliable, to document trends and create a common knowledge base that could be utilised in advocacy, policy development and service delivery.

The needs assessment project created a policy document and recommendations that bring life and context to an otherwise abstract set of issues. The report marked a turning point for Australian understanding of the needs of sex workers with HIV and has made new discussions possible on incorporating new ideas into the work of our sectors.

Findings of the research

Twelve of the 13 participants felt that their HIV-positive status did not define them as sex workers.

“I am either a sex worker or I am positive in my life, the two don't mingle… They don't need to. I mean if all of us [sex] workers don't think that way then why do you guys do? We are a sex worker, it's like saying “Hi, I am a positive truck driver” or “Hi, I'm a positive doctor”. You're not! You're a doctor that does their job. You know, the whole thing, what we should be teaching people, is you treat everybody as positive… I have studied first aid; when you find a patient, you treat them as infectious. Bang – that's it. We don't think of [ourselves as] being different to negative sex workers, so you guys shouldn't.”

“Just because you're a positive sex worker doesn't mean that you are deliberately spreading HIV.”

“If you go around deliberately giving people HIV it is a criminal offence and you do go to jail for it. Which I think is fair enough.”

“I would like to see everyone take responsibility for their own sexual health. I don't think the onus should always be on the positive person, to protect society. Everyone is responsible for their own actions and health.”

In the current climate of increasing prosecutions of people with HIV, participants had a heightened awareness of the need to prevent HIV transmission and expressed frustration and resentment at the unequal burden being placed on them because they are HIV-positive. They called for strategies to equalise responsibility between sex workers and clients, and between those who are HIV-positive and HIV-negative. They felt the focus on “criminal transmission” was putting them under increased pressure and all of them knew of or had experienced the negative effects of this.

Sex workers can act as safe sex educators, but this should not be legislated or written into criminal law. The sex education that clients receive from sex workers is good for public health, and should be encouraged through de-regulation of the sex industry, funded peer education and through actions such as constructive leadership and supportive policies by Government that recognise the public good that sex workers are doing through sex work. Updating sex work laws to embrace these contemporary understandings of public health and social good are a task for governments all over Australia.

The criminalisation of sex work maintains and promotes false stereotypes about sex workers in the public consciousness by stigmatising sex workers as deviant, immoral or damaged people who represent a health or moral risk to the general community. This stigmatisation and criminalisation is based purely on an occupational choice but it has profound impacts.

The needs assessment report, activities and recommendations

These findings were published as a report entitled The National Needs Assessment for Sex Workers Who Live with HIVCitation12 in August 2008 and disseminated through a number of forums and presentations, at the NSW State Library and the Australian National Library, and a number of university libraries. It was also made available on the Scarlet Alliance website. Copies were sent to AIDS Councils and other HIV sector organisations, organisations of people living with HIV and relevant health ministers (State, Territory and Federal Government) across Australia.

The needs assessment explained that: “A key issue for all HIV-positive sex workers is self-protection. Protecting ourselves from the hysteria and over-reaction of people who do not know our lives, who do not understand what the situation is like and who only see the disease and the sex work and not the human being. In order for this protection to be maintained, we ask that others advocate for us, and this report is what we are presenting in order for you all to advocate effectively.”

The assessment gave a clear message that criminalisation must be challenged: criminalisation of sex work, criminalisation of people with HIV, and criminalisation of being a sex worker living with HIV. Criminalisation is at the core of issues of stigma, discrimination and fear. In September 2008, a joint statement from the HIV sector challenging criminalisation was announced. The statement was signed by representatives of Australia's national peak HIV organisations, as well as state and territory AIDS Councils, and national sexual health and HIV research centres, and was sent out in a media release.Citation13 The statement categorically demanded the decriminalisation of HIV and sex work:

“Criminalisation is not and has never been an effective public health response to HIV prevention. It does not reduce HIV transmission – and the resulting stigma and discrimination increase barriers to effective health promotion. Current laws in certain Australian jurisdictions counteract the promotion of condoms, lubricant and shared responsibility, and the uptake of HIV testing and treatment, and therefore undermine effective public health… Laws that criminalise HIV positive people, including sex workers, are inconsistent with current good public health practice and should be repealed. National guidelines have been agreed. Government, community and health services must now implement these agreed guidelines.”

| • | provide accurate and easy to understand legal and health information for sex workers with HIV; | ||||

| • | provide updates on legal and social environments affecting sex workers with HIV; and | ||||

| • | improve public health policies to reduce stigma, including measures to encourage compliance by health professionals. | ||||

| • | decriminalise sex work for people with HIV in ACT, Victoria, Western Australia and Queensland; | ||||

| • | develop nationally consistent state-based legislation for HIV positive sex workers; | ||||

| • | ensure that legislation around sex work for people with HIV reflects legislation relating to private sex; | ||||

| • | remove disclosure requirements from state laws in New South Wales and Tasmania; and | ||||

| • | introduce anti-discrimination laws for sex workers in all jurisdictions. | ||||

Acknowledgements

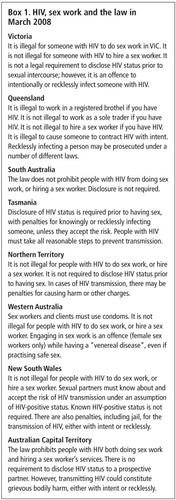

Part of this article is updated from a presentation given by Elena Jeffreys at the launch of the National Needs Assessment of Sex Workers Who Live with HIV, 18 July 2008, Surry Hills, New South Wales, and at the Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations General Meeting, 8 November 2008, Potts Point, New South Wales. The box with the laws on sex work and HIV in Australian states was compiled and checked by Scarlet Alliance and the New South Wales HIV/AIDS Legal Centre. Scarlet Alliance recognises the individuals who worked on the needs assessment and produced the report. The work achieved by Kane Matthews, project officer; the steering committee; Eva Cox, our research advisor; and Janelle Fawkes, CEO of Scarlet Alliance, far exceeded all expectations that the Scarlet Alliance Executive had of this project when it was first planned. Recognition is also given to the Elton John Fund and the AIDS Trust for being concerned about issues for sex workers living with HIV and investing in this project.

Notes

* The Grim Reaper campaign was run through television and mainstream print media for a short time in 1987. It used a ten pin bowling alley as a metaphor for the fatal consequences of HIV infection. The general public were the bowling pins and the Grim Reaper (Death) hurled HIV bowling balls down the alley knocking down men, women and children in a devastating portrayal of violent death. The commercial was serious and hard-hitting, and effective in raising awareness of the potential impact of HIV on the community. However, the long-term impact has been that nearly 30 years later, death and destruction remain as the pervasive images of HIV. See comment by Professor Ron Penny, retired head of Immunology, St Vincent's Hospital, Sydney.Citation1

References

- Penny R. Grim Reaper's demonic impact on gay community. 1 October 2002. At: <www.bandt.com.au/news/a0/0c0113a0.asp>. Accessed 5 December 2009. AIDS Action Council. Considerations for HIV/AIDS related campaigns. At: <http://aidsaction.org.au/content/for/students/campaign_considerations.php>. Accessed 16 February 2010.

- Development of a targeted prevention education and health promotion program for HIV. The National HIV/AIDS Strategy 2005-2008: Revitalising Australia's Response. Commonwealth Government of Australia, 2005. At: <www.health.gov.au/internet/main/Publishing.nsf/Content/health-pubhlth-strateg-hiv_hepc-hiv-index.htm#strategy. >.

- Australian Federation of AIDS Organizations. National AIDS Bulletins for 1987-2001. At: <http://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/1629911?lookfor=AIDS%20activities%20in%20Australia%202000-2010&offset=10&max=1587517. >.

- AIDS Action Council. Canberra, Newsletters from 2008. At: <www.aidsaction.org.au/content/publications/. >. Accessed 16 February 2009.

- D Reeders. Solutions to stigma. HIV Australia (newsletter of the Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations). 7(3): 2009

- Caution on $10M HIV plan. Sydney Star Observer. 20 April. 2008. At: <www.starobserver.com.au/news/2008/04/20/caution-on-10m-hiv-plan. >. Accessed 16 February 2009.

- Australian Capital Territory Prostitution Act 1992, Section 25.

- Matthews K. One step forward, many steps back. MEDIA SX News Guest Opinion and ABC Opinion, 1 October 2008.

- N Rudra. Prostitutes afraid to check for HIV. Canberra Times. 5 September. 2008

- Pos worker won't get fair trial. Scarlet Alliance. Media release. 31 January 2008.

- Victorian sex workers join national condemnation of ACT Government. VIXEN, Victorian Sex Industry Network. Media release. 12 February 2008.

- K Matthews. The National Needs Assessment of Sex Workers Who Live With HIV. 2008; Scarlet Alliance: Sydney.

- HIV is a virus not a crime. Australian HIV organisations respond. HIV Organisations Coalition media release. 19 September 2008.