Abstract

It has been widely documented in patrilocal and strongly patrilineal settings in India that the presence and influence of mothers-in-law in the household may affect fertility decisions made by young couples. However, not much is known about how intra-family relationships per se influence choice of contraceptive method and timing of use. To understand patterns of family planning decision-making, we carried out short, open-ended interviews in rural Madhya Pradesh in 2005 with 60 mothers-in-law, 60 sons and 60 daughters-in-law from the same families. Mothers-in-law were found to have an important influence on family decisions pertaining to activities within the household. They were also likely to influence the number of sons their daughters-in-law had and the timing of their daughters-in-law being sterilised, but they did not seem to have the same authority or influence with regard to decisions on the use of reversible contraceptive methods, which were mainly being made by young couples themselves. The findings show the flexibility and transformability of intra-family interactions, even within a hierarchically-ordered kinship system that is often considered an obstacle to improving reproductive health and gender equity. Given the right information, and availability of and access to reversible methods, young couples in rural Madhya Pradesh are increasingly making contraceptive choices for themselves.

Résumé

Dans les environnements patrilocaux et fortement patrilinéaires de l’Inde, le fait que la présence et l’influence des belles-mères dans le ménage affectent les décisions des jeunes couples sur la fécondité a été largement documenté. Néanmoins, on connaît mal la manière dont les rapports au sein de la famille influencent en eux-mêmes le choix de la méthode contraceptive et le moment de son utilisation. Pour comprendre les modalités de décision en matière de planification familiale, nous avons mené de brefs entretiens ouverts dans le Madhya Pradesh rural avec 60 belles-mères, 60 fils et 60 brus des mêmes familles. Nous avons constaté que les belles-mères exerçaient une forte influence sur les décisions familiales concernant les activités dans le ménage. Elles tendaient aussi à influer sur le nombre de fils qu’avaient leurs brus et le moment où celles-ci étaient stérilisées, mais elles ne semblaient pas avoir la même autorité ou influence sur le choix des méthodes contraceptives réversibles, qui dépendait principalement des jeunes couples eux-mêmes. Ces conclusions montrent la souplesse et la capacité de transformation des interactions dans la famille, même dans un système de parenté ordonné hiérarchiquement qui est souvent considéré comme un obstacle à l’amélioration de la santé génésique et de l’équité. Avec des informations exactes, la disponibilité de mesures réversibles et la possibilité d’y avoir accès, les jeunes couples du Madhya Pradesh rural font de plus en plus par eux-mêmes leurs choix contraceptifs.

Resumen

En India se ha documentado ampliamente en ámbitos patrilocales y muy patrilineales que la presencia e influencia de suegras en el hogar podría afectar las decisiones de parejas jóvenes en cuanto a la fertilidad. Sin embargo, se sabe poco acerca de cómo las relaciones intrafamiliares en sí influyen en la elección del método anticonceptivo y en el momento en que se empieza a utilizar. Para entender los patrones de la toma de decisiones sobre la planificación familiar, en 2005 realizamos entrevistas abiertas cortas, en las zonas rurales de Madhya Pradesh, con 60 suegras, 60 hijos y 60 nueras de las mismas familias. Se encontró que las suegras tienen una importante influencia en las decisiones de la familia respecto a las actividades del hogar. Además, era probable que influyeran en el número de hijos que tenían sus nueras y en el momento en que sus nueras eran esterilizadas, pero aparentemente no tenían la misma autoridad o influencia en cuanto a decisiones sobre el uso de métodos anticonceptivos reversibles, las cuales eran tomadas principalmente por parejas jóvenes. Los hallazgos muestran la flexibilidad y transformabilidad de las interacciones intrafamiliares, incluso en un sistema de parentesco de orden jerárquico que a menudo es visto como un obstáculo para mejorar la salud reproductiva y la equidad de género. Con la información correcta y la disponibilidad y accesibilidad de métodos reversibles, las parejas jóvenes en las zonas rurales de Madhya Pradesh cada vez más están tomando decisiones anticonceptivas por sí mismas.

The recent decade has witnessed a growing interest in understanding how couple communication influences contraceptive use in the developing world. Demographic and Health Surveys report that, in general, communication between spouses about family size and family planning is limited in many countries in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.Citation1Citation2 Nonetheless, numerous studies have reported a positive association between spousal communication and contraceptive use.Citation3–6 Almost all studies conclude that a more couple-oriented approach is the key to successful family planning programmes. However, this limited focus often ignores an important reality in many couples’ lives — that couples are often not the sole decision-makers regarding contraceptive use, particularly in cultures where extended kinship relations and lineage structures have a socially determining role.Citation7

Few studies have looked at the impact of family members and others on the sexual and reproductive health of young couples.Citation7–9 While these few persuasive qualitative studies on the family dynamics behind Indian women’s reproductive choices attest to the central importance of mothers-in-law,Citation10–12 there is very little systematic empirical evidence on the extent to which family interactions affect contraceptive method choice. In India, female sterilisation is the predominant method used, while according to the National Family Health Survey (2005), overall use of all modern reversible methods is barely 10% (and in rural India, 7%).Citation1

The impetus for the present study emerged from a five-year sexual and reproductive health intervention in rural Madhya Pradesh (2001–2005), implemented by a contraceptive social marketing organisation.Footnote* The goal of the intervention was to address unmet need for contraception, by making reversible contraceptive methods (mainly condoms and oral contraceptives) available and accessible using a social marketing model. In casual discussions during the intervention project, rural women often mentioned that mothers-in-law were opposed to young women’s desire to limit family size. It was therefore felt relevant to ascertain whether mothers-in-law were really as powerful and domineering as young women suggested.

The research on this question was initiated six months after Project Mandi was completed, as part of broader research on male involvement in reproductive health. Three different data sets were gathered in the study area: a survey among currently married men, focus group discussions and family interviews. The views of men on female sterilisation were published in 2009.Citation13 In the family interviews, we studied the interplay between mothers-in-law, sons and daughters-in-law as regards contraceptive decision-making, focusing on the use of reversible contraceptive methods. We aimed to answer the following questions: How does the mother-in-law influence young couples’ contraceptive choice in a kinship system characterised by strong inter-generational power asymmetries, an ideal of extended, patrilocal households and pronounced patrilineal ideology, such as in rural Madhya Pradesh? Are household power dynamics as regards family planning transformed when reversible contraceptive methods are made available?

The study area

Kinship practice among Hindus in the state of Madhya Pradesh corresponds largely to the North Indian model, in which patrilines formed by males are the backbone of society. Traditionally, only sons have had the right to inherit, and in land-owning and better-off households, daughters are married off with a dowry into an unrelated and unknown family, generally far from their natal village. The young wife enters a household of strangers in which men and secondarily older women hold decision-making power.

The data reported here were collected in Sehore district, about 50 km from the state capital, Bhopal, from August to September 2005. About 73% of the state population lived in rural areas, and 98% of families self-identified as Hindus. According to the National Family Health Survey (2005), the total fertility rate of Madhya Pradesh was 3.12 (3.34 in rural areas), compared to the national rate of 2.68 (2.98 in rural India). According to the 2001 census, about 70% of the population depended on agriculture for their income. The sex ratio in 2001 was 933 females to 1000 males, the birth rate was 32.3 per 1000 persons and about 50% of women and 70% of men were literate.Citation14

In 2005, the contraceptive prevalence rate in Madhya Pradesh was 55.9% (54.1% in the rural areas), among which 46.9% of eligible couples were using female sterilisation.Citation1 Due to the intervention that preceded this research, the research area had a much higher prevalence of reversible contraceptive use (29%)Citation13 than rural Madhya Pradesh as a whole (3.5%).Citation14 Thus, we could examine how they made sense of the introduction and use of reversible contraceptive methods within a rural hierarchical family system.

The study

For this study, 12 villages were purposively selected from among the villages involved in the social marketing intervention. The aim was to choose all households where young married couples and the parents of the young husband were in regular day-to-day interaction. Information on the number of eligible couples residing together within the same household was gathered, and all households in the 12 villages where the mother-in-law, son and daughter-in-law were all living in the same house, or where the mother-in-law lived close by in the neighborhood, were listed. Based on this listing, five families per village were randomly selected, one from the centre and four from the four corners of the village, to ensure that the sample was representative. In case of joint families, in which more than one eligible couple resided together, an equal proportion of eldest, middle or youngest were selected as the index couple. A total of 60 households from the 12 villages were interviewed over a one-month period. First, the purpose of the study was explained to all three family members individually. If all three gave verbal consent, they were included in the study. In all, 180 members of 60 families completed the interviews.

Short, open-ended interview guides were used. There was no flexibility in the wording or order of the questions, although the responses were open-ended. This interview technique is useful for reducing bias in a qualitative study when several interviewers are involved.Citation15 The interview schedule covered demographic background (current age, education, age at marriage, number of children, family type — nuclear or joint); communication and decision-making within the family, how household decisions were made and conflicts resolved and who had the final authority; discussion within the family about the need for family planning, who participated, considerations based on the need for spacing children or stopping further pregnancies, and who made the decisions; knowledge and use of reversible contraceptive methods among the young couples; and mothers-in-laws’ involvement with respect to reversible vs. permanent methods.Footnote*

The interviews aimed to assess current household and health decision-making patterns, including family planning decision-making and use. However, the innovative feature of the methodology was that three members, the mother-in-law, her son and her daughter-in-law, were interviewed separately and concurrently, so that the opinions of each remained independent. This is an important consideration in a hierarchical social situation in which the daughters-in-law, specifically, are not expected to air views contrary to those of their elders or their husbands. Each interview was carried out in privacy, and strict confidentiality was maintained. This method required both a clear definition of what should be elicited from each participant within the family and three well-trained research assistants: one man, who interviewed the sons, and two women, who interviewed the older and young women. Interviews were tape-recorded. However, if a respondent objected to being taped, short notes were taken and elaborated immediately after the interview on pre-formatted sheets, to minimise any recall bias.

The interviews were transcribed on the same day by the interviewers, translated into English and entered into a document file containing material from all 60 families in order of interview. They were organised in a tabular form where the rows contained the specific questions asked and the columns had the responses from each of the three family members to each of the questions. Organising the data in this format helped the researchers compare responses across the three family members (horizontally) and also read the overall views of the three groups of interviewees (vertically). The findings emerged through content analysis, by identifying themes and putting together information relevant to each theme from each interviewee.

Profile of respondents

The mean ages of mothers-in-law, sons and daughters-in-law were 56, 32 and 27 years, respectively. Sixty-five per cent of the sons and 55% of the daughters-in-law were literate. A quarter of the daughters-in-law had had at least seven years of schooling. Only eight mothers-in-law had ever gone to school, up to primary level (four years). The majority of families lived in joint households (80%), which were similar to the regional profile,Citation14 and the couples living in nuclear households had their mothers-in-law staying very close to them or in a house in the same compound. Mothers-in-law had had an average of six live births while the young couples had had around three. At the time of the study, 25 of the 60 daughters-in-law had already been sterilised, 11 couples were using condoms and nine were using oral pills. Only one couple was using an IUD, two were using abstinence or the “safe” period and 12 couples were not using any method.

Knowledge of contraceptive methods

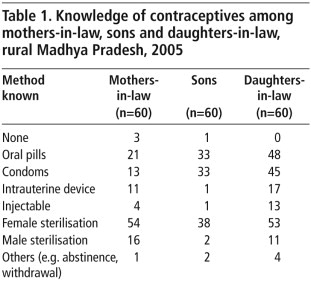

All 60 daughters-in-law clearly emerged as more knowledgeable about contraceptive methods than their husbands, including male methods like condoms, male sterilisation and methods requiring male cooperation, such as abstinence and withdrawal. Thirty mothers-in-law knew about female sterilisation only as a way to stop further conception; an additional 24 mothers-in-law were knowledgeable about some reversible methods as well (Table 1 ).

Sons reported obtaining information about family planning methods from television and from health workers in the community. Forty of them thought their wives were better informed about family planning methods than them, and hence they discussed these methods with their wives before making family planning decisions.

Influence of mothers-in-law on the sterilisation decision and on number of sons

As in all rural India, female sterilisation is the most widely used method of family planning in the research area. Mothers-in-law in the study clearly wanted to make decisions about daughters-in-law’s use of female sterilisation. Ten mothers-in-law had been sterilised themselves. They did not want their daughter-in-law to undergo the operation until she bore the number of sons the mother-in-law required. Male heirs are a crucial issue for kin groups in rural India, economically, socially and symbolically.

“I am the one who decides when my daughter-in-law needs to get sterilised. Unless there are at least two sons, there is no way that I am going to permit her to get it done.” (Mother-in-law 10)

“I will get both my daughters-in-law sterilised: first the elder one, then the younger. One son is a must, if not two. Until a son is born, the daughters-in-law will have to continue having children. No matter how many daughters are born, there will be no sterilisation for them unless the required sons are born.” (Mother-in-law 25)

“We (husband and wife) discussed the possibility of my getting sterilised after we had our two sons and one daughter. We asked my mother-in-law and she agreed.” (Daughter-in-law 4)

A strong son preference emerged not only from talking to sons and mothers-in-law; some daughters-in-law also felt very strongly about sons:

“I am the eldest daughter-in-law. I have three daughters and am currently pregnant again. But the desire to have a son is immense. I hope that this time I will have a son. My younger co-sister has two sons and so she is given a lot more importance than me in the household. I too want that position and I know I will get it only if I bear a son.” (Daughter-in-law 9)

Role of mothers-in-law in contraceptive decision-making

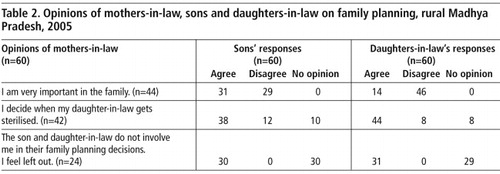

A discrepancy emerged in the interviews between the younger women’s evaluation of the general importance of their mother-in-law in the family, and her role in decisions concerning sterilisation. Only 14 of the 60 daughters-in-law thought their mother-in-law’s authority was important in the family generally, while 44 acknowledged her authority regarding female sterilisation (Table 2). A majority (42) of the mothers-in-law themselves opined that they had and should have the final say in their daughters-in-law being sterilised, but they considered communication on other contraceptive use within the extended family as limited, even useless.

“Even if I feel like advising my daughters-in-law, what is the use? They will not listen and will do as they please.” (Mother-in-law 1)

“I am sure my daughter-in-law is using something to prevent pregnancy. She has probably discussed it with my son. I am never consulted in these matters at all.” (Mother-in-law 13)

“There is no such discussion within the family and so I am not even aware if my daughters-in-law are using any contraception. I am only aware that my eldest daughter-in-law is sterilised, which she informed me of after the procedure.” (Mother-in-law 12)

“Neither do I discuss such issues, nor does anyone discuss them with me. I do not have any interest in such things.” (Mother-in-law 17)

Twenty-one daughters-in-law viewed their mothers-in-law as interfering, even if they were not asked their opinion. This led to conflicts over the use of reversible contraceptive methods despite the belief that the older generation should not be involved.

”Although we had kept my mother-in-law out of the discussion about our using condoms, she somehow got to know and was annoyed with us, asking us to stop using them immediately. Fortunately, my husband is very understanding and so we continued using them.” (Daughter-in-law 2)

Role of sons in decision-making on reversible methods

Reversible contraceptive methods are categorised differently from female sterilisation among the population of the research area because they are for spacing, not limiting family size.Citation13 This places the decision-making into two somewhat different frames of reference.

More than half of the sons seemed not only knowledgeable about reversible methods (mainly oral pills and condoms) (Table 1) but were also involved in decision-making on and use of these methods. More than a third of the sons interviewed reported having ever used condoms and nearly as many reported ever use of oral pills by their wives. One son reported ever-use of an IUD by his wife. Twenty-five sons reported that their wives had been sterilised. Only six men reported not using any modern contraceptives at the time of the interview, due to attempts to conceive (two cases), or the wife being currently pregnant (two cases), or breastfeeding (two cases). It was remarkable that among the interviewees we did not find any couples (apart from the breastfeeding ones) having an unmet need for contraception. This is, however, not the case in rural Madhya Pradesh overall, where unmet need is 12.0% (5.7% for spacing, 6.3% for limiting). The relatively good family planning situation in the area is most probably a reflection of the earlier reproductive health intervention, which has made temporary methods much more available and heightened people’s awareness of them.Citation16

Half of all men interviewed reported that decisions concerning the use of reversible methods were made jointly between husband and wife. Despite the norm of male dominance, joint decisions on family planning do occur in rural Indian society. The role of conjugal communication appeared especially evident in decisions about using reversible methods. Thirteen additional men stressed their wives’ extensive role, while only 11 of the 60 excluded their wives from the decision-making altogether.

“My wife and I discussed delaying the second child after our first was born. We jointly decided to use oral pills. I procure these either from the hospital or the medical shop. Those who want to delay pregnancy and space children should use such methods. They are useful.” (Son 3)

Mothers-in-law’s negative views on reversible contraceptive methods

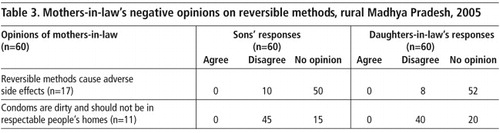

Seventeen of the 21 mothers-in-law who knew of any reversible contraceptive methods thought they caused adverse side effects, and did not approve of them, especially with regard to oral pills and IUDs.

”Oral pills lead to boils and menstrual disturbances. IUDs also cause swelling and ruin the uterus. This is the reason why women opt for female sterilisation.” (Mother-in-law 20)

Eleven of those same 21 mothers-in-law had very negative opinions on condoms, far more negative than those of their sons or daughters-in-law, none of whom agreed with them, and most disagreed (Table 3).

“When I went to the hospital with my daughter-in-law during the delivery of her last child, the doctor showed me some condoms and suggested that I ask my son and daughter-in-law to use them. I refused to even hold one in my hands. I don’t want such dirty things in my house.” (Mother-in-law 2)

“I have seen condoms strewn around the village. This is the most indecent thing and the government is doing wrong in promoting them. These things are for people with a bad reputation and those using it also get a bad name. On the other hand, sterilisation is a decent method to adopt.” (Mother-in-law 19)

“When there is sterilisation, why talk about other methods? They all cause problems.” (Mother-in-law 2)

Discussion

The households in the study are typical of rural Indian society as regards dominance based on age and gender. The role of the mother-in-law in the family was felt to be typical in such communities. Simple household decisions on daily chores like cooking and taking care of children are generally made by older women. Sons seemed to endorse the role of their mothers in the family and their position in the household. The younger women, in contrast, did not easily acknowledge the importance of the older women.Citation8,10,12,17

The influence of mothers-in-law in terms of young couples’ reproductive health in South Asia is considered to be significant. Studies have reported that when mothers-in-law were not living with the couple in the same household, the probability of those couples adopting modern contraceptive methods was higher. For example, a 1992 study by Jain et alCitation18 in India found that along with other factors such as age, number of living sons and female education, absence of mothers-in-law was also a factor influencing use of modern contraceptive methods. This finding was also reported in more recent studies (2003, 2006), and said to be due to the older generation having a higher family size preference and more conservative approach to innovations such as modern contraceptive methods.Citation8,19 In this qualitative study, no difference in views concerning the role of mothers-in-law in family planning issues emerged between the extended households and those where the mother-in-law was living close by. Irrespective of sharing or not sharing the rice pot, the intensive day-to-day interaction still appeared to have overarching importance.

According to Saavala’s qualitative studies in 2002 and 2006 rural South Indian young women are relatively satisfied with female sterilisation as a contraceptive method and feel that it relieves them of the domination of their mothers-in-law.Citation12Citation20 In the South Indian context, a young wife usually receives continuous support from her own natal family and may be sterilised even against her mother-in-law’s wishes. This differs from the Northern and Central Indian kinship practice, characterised in this study, in which a young wife tends to be much more dependent on her in-laws. However, in the South India study areaCitation12 reversible methods of contraception were practically non-existent, so the relationship between mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law as regards the sterilisation decision would be different.

This study reveals a more nuanced picture of inter-generational family relations in terms of family planning, as compared to earlier studies, which have mainly been interested in whether the mother-in-law hindered or enabled young couples’ use of family planning. Our findings show that decision-making on contraceptive use to some extent stands apart from other household decision-making. Although mothers-in-law did have a strong influence on timing of sterilisation for young women, based on the number of sons produced, this was often not the case for use of reversible methods.

In India, son preference is still widespread; 20% of women and men say they would like more sons than daughters while only 2–3% say they would like more daughters than sons.Citation1 Son preference and the desire for a family of at least three children have also influenced the timing of sterilisation in relation to fertility in India.Citation20

Even if temporary methods of contraception are mainly used for the purpose of birth spacing in rural India – and are thus benign from the perspective of fulfilling the required number of sons in the family – mothers-in-law in this study were not neutral or indifferent to them, though the small numbers mean they cannot be taken to represent the wider view.

In this study area, an intervention project made contraceptive pills, condoms and IUDs available and raised people’s awareness of these methods through information dissemination, street theatre, and the like. The spread of spacing methods may have had the consequence of creating in younger women a greater awareness of being able to control their own fertility, whatever the wishes of their mothers-in-law or husbands. With regard to the sons in this study, even though they paid heed to their mothers, they regarded decisions concerning use of reversible methods as their own. Although most daughters-in-law felt they were not in a position to be sterilised against their mother-in-law’s will, they saw any interference from her in the use of reversible methods as unjustified.

This study found that although mothers-in-law are considered to be the predominant authorities in the family regarding childbearing decisions in rural India, this is not a simple or unchanging truth. The findings support the empirical analysis of Rahman & Rao in 2004, that women’s autonomy is not solely a reflection of kinship structures.Citation21 Public services such as family planning may have an important, transformative effect on familial power relations, making it possible for young couples to make autonomous choices about spacing children.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Academy of Finland (Grant No. SA205648) for supporting the fieldwork of this study and the Doctoral Programmes in Public Health, University of Tampere, Finland, for supporting the analysis and writing of this article. Project Mandi was funded by Vaestoliitto, the Family Federation of Finland, Helsinki. Vaestoliitto and DKT India. They are also gratefully acknowledged for their support during the fieldwork and data analysis.

Notes

* Project Mandi, an initiative of DKT India, Mumbai.

* The terms used throughout the text are as follows: father-in-law refers to the son’s father, mother-in-law refers to the son’s mother and daughter-in-law refers to the son’s wife.

References

- International Institute for Population Sciences. National Family Health Survey. 2005; ORC Macro: Mumbai, India.

- K Miller, EM Zulu, SC Watkins. Husband-wife survey responses in Malawi. Studies in Family Planning. 32(2): 2001; 161–174.

- S Jejeebhoy. Convergence and divergence on spouses’ perspectives on women’s autonomy in rural India. 33(4): 2002; 299–308.

- MA Islam, SS Padmadas, PWF Smith. Men’s approval of family planning in Bangladesh. Biosocial Science. 38(2): 2006; 247–259.

- K Gayen, R Raeside. Communication and contraception in rural Bangladesh. World Health and Population. 9(4): 2006; 110–122.

- H Donner. Domestic goddesses: maternity, globalization and middle-class identity in contemporary India. 2008; Ashgate: Aldershot.

- Barnett B. Family planning use often a family decision. Network 1998;18(4):10–11,13–14.

- MM Kadir, FF Fikree, A Khan. Do mothers-in-law matter? Family dynamics and fertility decision-making in urban squatter settlements of Karachi, Pakistan. Journal of Biosocial Sciences. 35: 2003; 545–558.

- M Boulay, TW Valente. The selection of family planning discussion partners in Nepal. Journal of Health Communication. 10(6): 2005; 519–536.

- T Patel. Fertility behaviour: population and society in a Rajasthan village. 1994; Oxford University Press: Delhi, 287.

- P Jeffrey, R Jeffrey, A Lyon. Labour Pains and Labour Power: Women and Child-bearing in India. 1989; Zed Books: London.

- M Saavala. Fertility and Familial Power Relations: Procreation in South India. 2002; Curzon Press: Richmond.

- A Char, M Saavala, T Kulmala. Male perceptions of female sterilisation in rural central India. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 35(3): 2009; 131–138.

- Government of India. Census of India. New Delhi, 2001.

- MQ Patton. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. 2nd ed., 1990; Sage: Newbury Park, CA.

- Project Mandi: Mid-term evaluation report. DKT India, Mumbai, 2004. (Unpublished)

- P Vera-Sanso. Dominant daughters-in-law and submissive mothers-in-law? Co-operation and conflict in South India. Journal of Royal Anthropology Institute. 5: 1999; 577–593.

- A Jain, L Visaria, P Visaria. Impact of Family Planning Programme Inputs on Use of Contraceptives in Gujarat State. Working Paper No. 43. 1992; Gujarat Institute of Development Research: Ahmedabad.

- SA Qutub. Hope for the future: planning for sons. People Planet. 4(4): 1995; 23–24.

- M Saavala. Sterilised mothers: women's personhood and family planning in rural South India. L Fruzzetti, S Tenhunen. Culture, Power and Agency: Gender in Indian Ethnography. 2006; Stree Publishers: Calcutta, 135–170.

- L Rahman, V Rao. The determinants of gender equity in India: examining Dyson and Moore’s thesis with new data. Population and Development Review. 30(2): 2004; 239–268.