Abstract

An important determinant of family honour in many cultures is the chastity of women, with much importance attributed to virginity until marriage. The traditional proof of virginity is bleeding from the ruptured hymen, which has led some women to request genital surgery to “restore” virginity, or hymen repair. The aim of this study was to investigate whether Swedish health care providers have had experience of patients requesting this surgery. Questionnaires were sent to 1,086 gynaecologists, midwives, youth welfare and social officers, and school nurses and doctors in four Swedish cities. Of the 507 who returned the questionnaire, 271 had seen patients seeking virginity-related care. Of these, 14 had turned the patients away; 221 had made 429 referrals, mostly to a welfare officer or a gynaecologist; and 26 had referred patients to a plastic surgeon. Nine gynaecologists had carried out such surgery themselves. Swedish authorities have to date focused on this issue primarily from a social and legal perspective. No guidelines exist on how health professionals should deal with requests for surgery to restore virginity. Further research is needed on how best to meet the needs of this group of patients in a multi-ethnic society and how to address requests for hymen repair. Without this, medical practitioners and counsellors will remain uncertain and ambivalent, and a variety of approaches will persist.

Résumé

Dans bien des cultures, la chasteté des femmes est un déterminant essentiel de l'honneur familial, la virginité jusqu'au mariage revêtant une grande importance. La preuve traditionnelle de la virginité est le saignement lors de la rupture de l'hymen, ce qui incite certaines femmes à demander une chirurgie génitale pour « restaurer » la virginité, ou reconstruire l'hymen. Le but de cette étude était de déterminer si les soignants suédois avaient rencontré des patientes souhaitant cette intervention. Des questionnaires ont été envoyés à 1086 gynécologues, travailleurs sociaux et agents de protection de la jeunesse, infirmières et médecins scolaires dans quatre villes suédoises. Des 507 soignants ayant retourné le questionnaire, 271 avaient eu des patientes recherchant des soins liés à la virginité : 14 d'entre eux avaient éconduit les patientes, 221 les avaient orientées, principalement vers un travailleur social ou un gynécologue, et 26 avaient adressé les patientes à un chirurgien esthétique. Neuf gynécologues avaient pratiqué eux-mêmes l'intervention. Jusqu'à présent, les autorités suédoises se sont penchées sur cette question uniquement dans une perspective juridique et sociale. Il n'existe pas de directives sur la manière dont les soignants doivent traiter les demandes de restauration de la virginité. Les recherches doivent se poursuivre pour mieux satisfaire les besoins de ce groupe de patientes dans une société multiethnique et décider comment répondre aux demandes de reconstruction de l'hymen. Faute de quoi, les médecins et les conseillers demeureront dans l'incertitude et l'ambivalence, et des approches diverses perdureront.

Resumen

Un importante determinante del honor de la familia en muchas culturas es la castidad de las mujeres; se atribuye gran relevancia a la virginidad hasta el matrimonio. La prueba tradicional de la virginidad es el sangrado cuando se rompe el himen, por lo cual algunas mujeres solicitan cirugía genital para “restaurar” su virginidad, o reparación del himen. El objetivo de este estudio fue investigar si los prestadores de servicios de salud suecos han atendido pacientes que solicitaron esta cirugía. Se enviaron cuestionarios a 1086 ginecólogos, funcionarios de protección y asistencia social a la juventud, y enfermeras y médicos escolares en cuatro ciudades suecas. De las 507 personas que contestaron el cuestionario, 271 habían atendido pacientes que buscaban servicios relacionados con la virginidad. De éstas, 14 habían rechazado a las pacientes; 221 habían proporcionado 429 referencias, la mayoría a un funcionario de protección y asistencia social o a un ginecólogo; y 26 habían remitido a las pacientes a un cirujano plástico. Nueve ginecólogos habían efectuado la cirugía por sí solos. Hasta la fecha, las autoridades suecas han tratado este asunto principalmente desde un punto de vista social y jurídico. No existen guías sobre cómo los profesionales de la salud deben tratar las solicitudes de cirugía para restaurar la virginidad. Aún es necesario realizar más investigaciones sobre la mejor manera de atender las necesidades de este grupo de pacientes en una sociedad multiétnica y de atender las solicitudes de reparación del himen. De lo contrario, los profesionales médicos y consejeros continuarán con dudas y ambivalencia, y una variedad de enfoques persistirá.

In traditional patriarchal families, an important determinant of family honour is the chastity of female family members, with much importance attributed to the virginity of unmarried daughters.Citation1Citation2 In many cultures, the traditional proof of virginity when entering upon marriage has been bleeding from the ruptured hymen on the wedding night. This has endowed the hymen with a great symbolic value.Citation3 The requirement to bleed on the wedding night can lead to inner conflict for women, both those who have had sexual relations before marriage and those who fear they will not bleed, even though they are still virgins. Both are reasons why they might request genital surgery. Their fears, according to a Dutch study, arise from threats or fear of violence, such as “honour killing”, and can lead to severe psychological problems, including depression, despair, suicidal feelings and identity problems.Citation4

The threat of honour violence in Sweden

Discussion around “honour killing” arose in Sweden in the late 1990s. In the Scandinavian context, the term denotes the oppression, threat of or actual violence that some mainly young women experience from family members, justified as the only way to preserve the honour of the family. In reports commissioned by Swedish authorities on both the national and local level, the expression “vulnerable girls in patriarchal families” was introduced to describe the group at risk.Citation5 In the absence of actual data, a 2007 report from the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare estimated the number of girls at risk of honour-related violence and virginity problems to be 600-4,500 nationally.Citation6 The estimate is based on statistics from the Population Register of the number of young women living in Sweden born in the Middle East or North Africa, or born in Sweden with at least one parent from those regions, and on the prevalence of honour killing in their countries of origin.

From a medical perspective, research on and reports of crimes related to chastity and virginity are very rare in Sweden, but they tend to be treated as a form of domestic violence, with the difference that the assault is not necessarily by an intimate partner but instead is planned, sanctioned and executed by parents or other family members.Citation7Citation8 Studies of domestic violence in areas of the world where honour killing is reported to occur describe the resulting physical and mental morbidity, as well as mortality through suicide or homicide.Citation8Citation9 Research on honour violence by a partner is thin in general. In Sweden, the authorities have focused their efforts to counter such violence mainly on its social and legal aspects. Guidelines at the state, county and municipality levels are based on the work of voluntary organisations, social welfare agencies, the police and school authorities, but to a lesser extent medical and health care services.Citation10

Virginity, the hymen and hymen “repair”

From a gynaecological perspective, not all women experience bleeding when they first have intercourse. Two studies in English report that 40–80% of women do not bleed upon initial coitus.Citation8,11 Factors that may increase the likelihood of bleeding at that time are forced sexual relations, lack of arousal or lubrication, vaginal infection, genital malformation (e.g. imperforate hymen), generalised bleeding disorder, or if the girl is pre-puberty. Studies in forensic medicine, intended for use as evidence when prosecuting alleged sexual assault against a minor, reveal very few cases where a physician can make a definitive statement as to whether gynaecological examination of the hymen indicated past vaginal intercourse or not.Citation12–14 To our knowledge, no studies have found reliable evidence of hymen rupture in adolescent girls following voluntary vaginal intercourse. Hence, from an anatomical point of view, the state of the hymen has in reality little to say about previous sexual activity or experience. However, it is still reported, e.g. from Turkey, that midwives and gynaecologists are requested to perform “virginity examinations” to prove to the family that a young woman has not had premarital relations.Citation15–18

Prior to this study, public reports in Sweden have showed that personnel at youth clinics and school youth services do come in contact with young women with problems related to what for them is defined and acted upon as “family honour”.Citation6,19 It has also been our experience in hospitals in Malmö, Göteborg and Stockholm that young women seek medical counselling with questions and concerns about virginity and female anatomy. To the best of our knowledge, there are no rigorous studies with evidence that the surgical procedure called hymenoplasty or “hymen repair”, using stitches in the vagina, actually leads to bleeding from the vagina on the wedding night. Yet this surgery seems to be a growing phenomenon in Western countries, at least according to journalists. Nevertheless, we have found no prevalence studies and there seemed to be a lack of information about the extent to which Swedish health care providers have encountered patients seeking such surgery, or how they have handled these requests. No reliable data exist regarding how often surgical procedures to “restore virginity” are performed in Sweden either by plastic surgeons or gynaecologists in private or public hospitals. The aim of this study was to investigate the extent to which Swedish health care providers have had experience of patients requesting counselling or surgery for “hymen repair” or “virginity restoration” and what they did in response to such requests.

Methodology and participants

The theoretical underpinnings of the study were based on the following hypotheses: First, health care providers have had experience of patients from non-Swedish cultural backgrounds with honour-related virginity issues, as well as with young Swedish women with sexual problems. While this population of patients is well-defined and studied in general, the group of young women living in traditional patriarchal families where family honour depends on their chastity is a hidden group. Therefore, health care providers might not be meeting their needs, due to a lack of knowledge and guidelines on how to approach these issues. A questionnaire was designed to elicit the extent of their experience and how they addressed these problems when patients presented to them.

We devised a questionnaire to be completed anonymously. It was sent out by mail to a) gynaecologists at departments of women's health at public hospitals; b) personnel at public youth clinics, e.g. welfare and social officers and midwives, both serving young women under the age of 20; c) midwives providing contraceptive counselling at public health clinics; d) school nurses, and e) school physicians in four Swedish cities: Malmö, Göteborg, Stockholm and Örebro. Official mailing lists containing a total of 1,086 health care providers at these facilities were used. The selection of cities and facilities was based on where the largest population of foreign-born residents with North and East African, Middle Eastern and other Muslim backgrounds lived in Sweden. In the four cities 15-26% of women are foreign born, compared to an average of 10% among the Swedish population overall (Statistics Sweden, 2009). People from the Middle East are one of the largest non-Nordic immigrant groups in these cities.

To our knowledge, there is currently no consensus on the meaning of “honour violence” or “virginity problems”; hence, no precise definitions of these could be provided in the questionnaire. However, an introduction to the aims of the study and an outline of the different problems involved, our clinical experience, and earlier research on the subject,Citation3,20,21 were included with the invitation to participate in the study. The questionnaire was piloted and slightly revised with the help of sexual and reproductive health care and social welfare experts. It was then reviewed and given ethical approval by the County Administrative Board of Skåne, the Swedish Government agency responsible for policies related to intimate partner violence and honour-related violence in Sweden.

The final questionnaire contained eight structured questions. The only background information asked for regarding the respondents was profession, city and place of work. Health care providers were asked whether or not they had seen patients seeking help for honour-related virginity problems (question 1), and approximately how many such patients they had seen (question 2). No time limit within which they may have encountered these patients was specified. Questions about clinical care and treatment covered whether the patients' requests had been rejected (question 3) or the patients were referred elsewhere (question 4), and in cases of referral, to what kind of specialist or other expert. Options were provided and more than one answer could be given (question 5). Physicians were also asked if they had ever performed any surgical procedures to “restore virginity” (question 6). All participants were asked if they considered that they had sufficient knowledge of how to respond to virginity problems (question 7), and whether they believed the health care sector should see and treat patients requesting this kind of genital surgery (question 8). Finally, space for comments was provided. In order to avoid recall bias, we did not focus on the specific number of patients seen or when, but more on the phenomena in general.

The questionnaires were distributed by mail beginning in September 2004. At the cut-off date in June 2005, 1,086 questionnaires had been sent out and 507 were filled out and returned (response rate 47%). Answers were sorted according to profession and answers to the structured questions analysed by descriptive statistics.

Return of the completed questionnaire itself served as informed consent (Personal communication, Professor M Stjernquist, member, Ethical Committee, Lund University, Sweden, March 2005). In focusing the investigation on health care providers rather than patients, we sought to avoid putting more strain on this patient group, who are at risk of violence. We also avoided questions that would make it possible to trace responses to any specific patient.

Findings

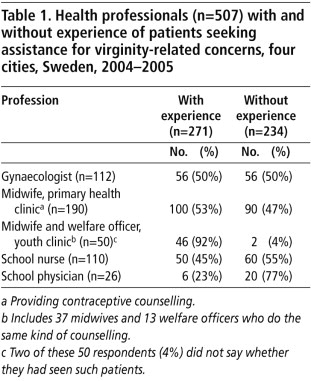

The responses showed that 271 (53%) of 507 health care providers working in adolescent gynaecology and women's health in four Swedish cities have, at one time or another, seen about 520 patients seeking care for honour-related virginity issues (Table 1 ). The highest numbers were reported by midwives at youth clinics, but half of the gynaecologists at hospitals had also seen women with these problems. The midwives and welfare officers at youth clinics (92%) had had most experience, followed by midwives at primary health clinics (53%), school physicians (53%), gynaecologists (50%), and school nurses (45%).

In their estimations of the age of patients they encountered, 167 thought the patients were younger than 18 years of age and 156 had seen patients they thought were older than 18 years. Girls under the age of 18 were seen mainly by youth and school personnel, but also by two of the 112 gynaecologists. The majority of the girls over 18 were seen by midwives at primary health clinics and by gynaecologists. The numbers each respondent reported seeing ranged from one to 100, with a median of two. All respondents had had more than two years' working experience. None of the respondents reported seeing patients requesting hymen repair in relation to female genital mutilation/cutting.

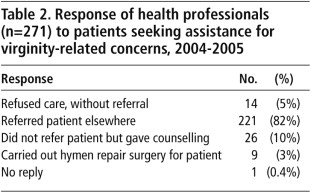

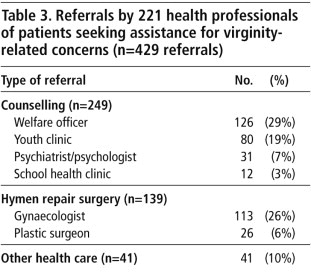

Table 2 shows how the different providers responded to the patients. Of the 271 health professionals who had seen such patients, 14 (5%) refused to provide the care the patients asked for, without referring them elsewhere. Of these, nine were gynaecologists, two were school nurses and three were midwives at public health clinics. However, 221 (82%) did refer patients elsewhere, while 45 (10%) provided treatment or care without further referral. One did not answer this question. Nine gynaecologists reported having performed genital surgery to “restore virginity” themselves, all carried out at public, non-profit hospitals. The 221 respondents made 429 referrals for counselling, surgery, and other care/treatment, in some cases to more than one specialist or authority. Of these referrals, the greatest number were to a welfare officer, psychiatrist or psychologist, youth or school health clinic (58%) for counselling, while 32% were to a surgeon known to do hymen repair, either a gynaecologist or plastic surgeon. The rest were to a range of other health professionals (Table 3 ). Aspects of the problem involving the patient's social situation, including threats of violence or actual violence, were likely to result in referrals to a welfare officer.

In response to the question of whether, in the respondents' view, the health sector should provide care in response to requests for virginity restoration, along with social service agencies and school authorities, 456 of the 507 (90%) said yes, the medical and health care services should see and treat such patients. Importantly, however, only 12% (61) of these 507 respondents considered themselves to have sufficient knowledge of preventative work, such as psychological counselling and social support, in relation to honour- and virginity-related problems. These 61 respondents included 10 of the 50 midwives and welfare officers at public youth clinics; 20 of the 110 school nurses; and 31 of the 190 midwives at primary health clinics (data not shown).

Finally, of the free comments made by these providers, the following represent the views of the majority of those who responded and the more interesting comments. First, many commented that the health sector needed a clear strategy for a care plan of action. The majority of the respondents were of the opinion that the medical and health services, as well as social services agencies and school authorities, should be included in addressing this complex problem. Midwives said, for example: “Parents sometimes request a certificate of virginity in spite of the girl having a boyfriend and having intercourse with him” or “Young women asked questions about the risk of using tampons”. Issues of this kind are closely related to honour-linked attitudes, although they do not necessarily mean every patient is subjected to violence. One midwife working at a youth clinic commented: “I try to inform them about virginity, but if they cannot be convinced [not to have the surgery], mostly out of fear, they are given the telephone number of a private plastic surgeon.”

Many respondents stressed the importance of preventative work and responding to patients' expressed needs at different levels. This included the importance of increasing general knowledge of female anatomy among girls and young women and the likelihood of and reasons for vaginal bleeding at first intercourse, in order to reduce false assumptions and prejudice; the necessity of changing the attitudes of society as a whole, especially among young men approaching marriage age and certain immigrant and ethnic minority groups, and the importance of meeting the needs of individual patients.

Discussion

The results show that many of the health professionals who responded to our questionnaire have seen patients with virginity-related problems, indicating that young women with these problems are seeking care and support from the health sector. The fact that the referrals made by the respondents to others included social workers, welfare officers, youth clinics, gynaecologists and plastic surgeons suggests that both social and medical aspects of the problem lead women to seek care.

The health professionals who responded said they had few guiding principles for how to respond in this area. Guidelines on course of action regarding social and legal aspects of virginity- and honour-related issues, but not the health aspects of these problems, have been issued by the Swedish authorities. These include referral to protected accommodation when violence has been threatened or taken place and education for police and lawyers.Citation5Citation6 However, we found that a large proportion of health and welfare professionals had referred patients to a gynaecologist or plastic surgeon, but 17% handled patients on their own.

This study clearly shows the wide range of providers who meet not only young adult women but also girls younger than 18 with virginity-related problems. These findings make us think that adolescent girls from ethnic minority backgrounds consider Swedish youth clinics as trustworthy in seeking to resolve these problems, though this would need to be confirmed through research with them. In general, little is known about the sexual health needs of the young women from immigrant backgrounds whose requests for services are identified here.Citation10 Future research should focus on this potentially vulnerable group.

Whether or not to perform hymen repair surgery has been much debated in both medical and medical ethics journals.Citation22–25 The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare's Ethical Committee's Protocol No.43 (19 March 2004) discusses this surgery as an option when the woman's life is in danger but no guidelines are provided. A report on vulval disease from the Swedish Association of Obstetrics and Gynaecology contains a similar discussion, although without presenting any evidence that this surgery meets the needs of the patient.Citation26 Moreover, while it is clear that this surgery is being performed, it is unknown to what extent, or with what outcomes or complications. We have not been able to find any clinical studies of hymen repair surgery in which women were followed up afterwards, except for one letter, which stated that ten women who had had long-term follow-up, and their surgeons, were satisfied with the results of the surgery. Even then, “satisfied” was not defined.Citation27

We investigated the legality of surgical alteration of the genitals in 2004, and found then that plastic surgeons in private practice were experiencing an increased demand for cosmetic genitoplasty.Citation28 While 26 health care professionals referred a patient seeking assistance for virginity problems to a plastic surgeon, we do not know how many plastic surgeons this included. Only nine of the 112 gynaecologists who responded in this study had performed surgery aimed at “restoring virginity” themselves. Research would be needed to clarify if in fact private plastic surgeons are the main group carrying out this surgery at the present time. One recommendation could be that both public and private hospitals report this surgery centrally in order to have prevalence data available.

The fact that only 12% of the respondents thought they knew enough about how to respond to virginity-related problems is a challenge to the Swedish authorities and the health and welfare sectors for the future, and underlines the need for better evidence on what constitutes best practice. One gynaecologist suggested that the health sector needed to focus on medical aspects only, leaving other aspects to a wider network of involved agencies. There were no comments from respondents on how to address the patriarchal family traditions that sometimes lead to virginity- and honour-related violence, probably because these are areas where clinicians at least have no expertise. Perhaps this is because they are used to focusing on individuals, and to leaving social welfare and counselling needs to others to address. However, it has been our clinical experience that the phenomena of family honour and virginity problems are difficult to separate for patients seeking “restoration of virginity”, and this perception is supported by other research.Citation29–32

The study has some limitations. A response rate of 47% is low, but acceptable for a study based on a questionnaire distributed by mail. From an ethical perspective, the anonymity of the participants was a strength of the study. However, this made it impossible to send those not responding a reminder letter individually. Nor were we able to do an in-depth analysis of why some did not participate or ask those who did participate further questions. Recall bias is well known in questionnaire studies, which is why we did not focus on the specific number of patients seen, or the time period in which the visits occurred, but more on the phenomenon in general.

A much higher percentage of midwives and welfare officers responded to the questionnaire (98%) than other groups of health care providers. Generally, it is expected that the motivation to answer a questionnaire increases if the respondent is familiar with the subject; however, almost half of our respondents did not have such experience.

In our opinion, the number of returned questionnaires can be considered representative only for the cities and professions included in the study. No further conclusions about the experience of patients with honour violence and virginity-related problems among health care providers in the rest of Sweden should be drawn, nor should the respondents be seen as representative of other members of the same profession at a national level. Reporting of proportions of respondents answering the questions by discipline is appropriate. Any further analysis of demographic details, given the response rate and the questions, would be misleading.

Lack of information on the time period in which patients were encountered is another limitation of the study. However, to our knowledge this is the first study that has quantitatively investigated such experience among health care providers and those working in adolescent gynaecology and women's health at both the primary and hospital level. The choice of method made it possible to reach a rather large group of gynaecologists, midwives, welfare officers and school health professionals in cities with a mix of Swedish and ethnic minorities affected by these issues.

In conclusion, this study has confirmed that health care providers do encounter patients seeking assistance with honour-related virginity problems, including requests for hymen repair, which are of considerable importance to young women from certain cultural backgrounds living in Sweden. The findings indicate the need for further education and research on how best to meet the needs of this group of patients at the health care level in a multi-cultural society. Until there is a consensus on how to approach requests for restoration of virginity, medical practitioners, welfare officers and counsellors will remain uncertain and ambivalent, and a variety of approaches will persist.Citation18Citation33

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by grants from the County Administrative Board of Skåne and the Faculties of Medicine of Uppsala and Lund University, Sweden.

References

- N Shalhoub-Kevorkian. Towards a cultural definition of rape – rape and public attitudes. Women's Studies International Forum. 22(2): 1999; 157–173.

- MW Buitelaar. Negotiating the rules of chaste behaviour: re-interpretations of the symbolic complex of virginity by young women of Moroccan descent in the Netherlands. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 25(3): 2002; 462–489.

- P Bourdieu. The sentiment of honor in Kabyle society. JG Peristiany. Honor and Shame. 1966; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 223.

- M Bekker, J Rademakers, I Mouthaan. Reconstructing hymens or constructing sexual inequality? Service provision to Islamic young women coping with the demand to be a virgin. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology. 6(5): 1996; 329–334.

- Swedish Ministry of Industry Employment and Communications. Regeringens insatser för utsatta flickor i patriarkala familjer. [The government's actions for vulnerable girls in patriarchal families (Swedish)]. Fact sheet, 2002;07.

- Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. Frihet och ansvar – En undersökning om gymnasieungdomars upplevda frihet att sjölva bestömma. [Freedom and responsibility – a survey among teenagers regarding their perception of freedom and personal autonomy (Swedish)]. 2007; Socialstyrelsen: Stockholm.

- AD Kulwicki. The practice of honor crimes: a glimpse of domestic violence in the Arab world. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 23(1): 2002; 77–87.

- S Douki, F Nacef, A Belhadj. Violence against women in Arab and Islamic countries. Archives of Women's Mental Health. 6(3): 2003; 165–171.

- RL Fischbach, B Herbert. Domestic violence and mental health: correlates and conundrums within and across cultures. Social Science and Medicine. 45(8): 1997; 1161–1176.

- Stiftelsen Kvinnoforum. Honour related violence: European resource book and good practice. 2005; Kvinnoforum: Stockholm.

- S Paterson-Brown. Should doctors reconstruct the vaginal introitus of adolescent girls to mimic the virginal state? Education about the hymen is needed. British Medical Journal. 316(7129): 1998; 461.

- FA Goodyear-Smith, TM Laidlaw. What is an ‘intact hymen’? A critique of the literature. Medicine Science & Law. 38(4): 1998; 289–300.

- SJ Emans, ER Woods, EN Allred. Hymenal findings in adolescent women: impact of tampon use and consensual sexual activity. Journal of Pediatrics. 125(1): 1994; 153–160.

- K Edgardh, K Ormstad. The adolescent hymen. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 47(9): 2002; 710–714.

- N Alkan, A Baksu, B Baksu. Gynecological examinations for social and legal reasons in Turkey: hospital data. Croatian Medical Journal. 43(3): 2002; 338–341.

- N Shalhoub-Kevorkian. Imposition of virginity testing: a life-saver or a license to kill?. Social Science and Medicine. 60(6): 2005; 1187–1196.

- D Cindoglu. Virginity tests and artificial virginity in modern Turkish medicine. Women's Studies International Forum. 20(2): 1997; 253–261.

- JJ Amy. Certificates of virginity and reconstruction of the hymen. European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care. 13(2): 2008; 111–113.

- S Högdin. Var går grönsen? Föröldrars grönssöttning avseende ungas deltagande i sociala aktiviteter. En jömförelse utifrån etnicitet och kön. [Where to draw the line? Parental limits on participation of adolescents in social activities. A comparative study in relation to ethnic background and gender (Swedish)]. Sociologisk Forskning. 4: 2006; 41–65.

- JG Persitiany, J Pitt-Rivers. Honor and Grace in Anthropology. 1992; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- L Abu-Odeh. Crimes of honor and the construction of gender in Arab societies. M Yamani. Feminism and Islam, Legal and Literary Perspectives. 1996; Ithaca Press: Ithaca, 149–151.

- K Dalaker, C Loennecken. Operativ rekonstruksjon av jomfruhinner. [Surgical reconstruction of hymens.] (in Norwegian). Tidsskrift for Den norske Lœgeforening. 122(18): 2002; 1820.

- R Forde. Rekonstruksjon av jomfruhinner [Reconstruction of hymens.] (in Norwegian). Tidsskrift for Den norske Lœgeforening. 122(23): 2002; 2317.

- LF Ross. Should doctors reconstruct the vaginal introitus of adolescent girls to mimic the virginal state? Surgery is not what it seems. British Medical Journal. 316(7129): 1998; 462.

- I Usta. Hymenorraphy: what happens behind the gynaecologist's closed door?. Journal of Medical Ethics. 26(3): 2000; 217–218.

- E Rylander, L Helström, A Strand. Vulvasjukdomar. [Vulval disease (Swedish)]. 2003; Swedish Association of Obstetrics and Gynaecology: Stockholm.

- A Longmans, A Verhoeff, R Boal Raap. Should doctors reconstruct the vaginal introitus of adolescent girls to mimic the vaginal state?. British Medical Journal. 316: 1998; 459–460.

- B Essén, S Johnsdotter. Female genital mutilation in the west: traditional circumcision versus genital cosmetic surgery. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 83(7): 2004; 611–613.

- RJ Cook, BM Dickens. Hymen constructions: ethical and legal issues. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 107: 2009; 266–269.

- A Akpinar. The honor/shame complex revisited: violence against women in the migration context. Women's Studies International Forum. 26(5): 2003; 425–442.

- VA Goddard. Honor and shame: the control of women's sexuality and group identity in Naples. P Caplan. The Cultural Construction of Sexuality. 1987; Tavistock Publications: London, 167–192.

- C Arin. Femicide in the name of honour in Turkey. Violence against Women. 7: 2001; 821–825.

- M O'Connor. Reconstructing the hymen: mutilation or restoration?. Journal of Law and Medicine. 16(1): 2008; 161–175.