Abstract

The female condom has received surprisingly little serious attention since its introduction in 1984. Given the numbers of women with HIV globally, international support for women's reproductive and sexual health and rights and the empowerment of women, and, not least, due to the demand expressed by users, one would have expected the female condom to be widely accessible 16 years after it first appeared. This expectation has not materialised; instead, the female condom has been marginalised in the international response to HIV and AIDS. This paper asks why and analyses the views and actions of users, providers, national governments and international public policymakers, using an analytical framework specifically designed to evaluate access to new health technologies in poor countries. We argue that universal access to female condoms is not primarily hampered by obstacles on the users' side, as is often alleged, nor by unwilling governments in developing countries, but that acceptability of the female condom is problematic mainly at the international policy level. This view is based on an extensive review of the literature, interviews with representatives of UNAIDS, UNFPA and other organisations, and a series of observations made during the International AIDS Conference in Mexico in August 2008.

Résumé

Il est surprenant que le préservatif féminin ait reçu peu d'attention depuis son introduction en 1984. Compte tenu du nombre de femmes séropositives dans le monde, du soutien international à la santé et aux droits génésiques et à l'autonomisation des femmes, et surtout, de la demande exprimée par les usagers, on aurait pu penser que le préservatif féminin serait largement disponible 16 ans après son lancement. Or cette attente ne s'est pas matérialisée ; au contraire, le préservatif féminin a été marginalisé dans la riposte internationale au VIH et sida. Cet article se demande pourquoi et analyse les opinions et les actions des usagers, des fournisseurs, des gouvernements et des décideurs publics internationaux au moyen d'un cadre analytique conçu pour évaluer l'accès aux nouvelles technologies de santé dans les pays pauvres. Nous avançons que l'accès universel au préservatif féminin n'est pas principalement entravé par des obstacles du côté des usagers, comme on l'affirme souvent, ni par la réticence des gouvernements dans les pays en développement, mais que l'acceptabilité du préservatif féminin est problématique essentiellement au niveau politique international. Cette idée repose sur une analyse étendue des publications, des entretiens avec des représentants de l'ONUSIDA, du FNUAP et d'autres organisations, et une série d'observations pendant la Conférence internationale sur le sida organisée à Mexico en août 2008.

Resumen

Sorprendentemente, el condón femenino ha recibido muy poca atención seria desde su introducción en 1984. Dado el alto número de mujeres con VIH mundialmente, el apoyo internacional por la salud y los derechos reproductivos y sexuales de las mujeres, el empoderamiento de éstas y la demanda expresada por las usuarias, se esperaría que el condón femenino fuera ampliamente accesible 16 años después de su primera aparición. Esta expectativa no se ha materializado; al contrario, el condón femenino ha sido marginado en la respuesta internacional al VIH/SIDA. En este artículo se examina el porqué y se analizan los puntos de vista y las acciones de usuarias, prestadores de servicios, gobiernos nacionales y formuladores de políticas públicas internacionales, utilizando un marco analítico diseñado específicamente para evaluar el acceso a nuevas tecnologías de salud en países pobres. Argumentamos que el acceso universal al condón femenino no es obstaculizado principalmente por el lado de las usuarias, como suele alegarse, ni por gobiernos que no están dispuestos en países en desarrollo, sino que la aceptación del condón femenino es problemática en el nivel internacional de políticas. Esto se basa en un análisis extenso del material publicado, entrevistas con representantes de ONUSIDA, UNFPA y otras organizaciones, y una serie de observaciones realizadas durante la Conferencia Internacional sobre el SIDA, celebrada en México en agosto de 2008.

Since the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, condoms have been the single most efficient available technology to reduce the transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). In 1984, Lasse Hessels invented the female condom, a transparent sheath with the same length as the male condom and a flexible ring at each end. In 1993, the United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) approved the female condom as a safe and effective contraceptive and protective device impermeable to various STI organisms, including HIV. The American Foundation for AIDS Research stated that the female condom is 94–97% effective in reducing the risk of HIV infection, if used correctly and consistently.Citation1 The potential contribution of female condoms to STI/HIV prevention is well documented,Citation2–6 and highly cost-effective.Citation7 A review of 137 articles on the female condom concluded that it is effective in increasing protected sex and lowering STI incidence.Citation8 A significant number of studies have also demonstrated that a wide range of choice of contraceptive methods and STI/HIV prevention devices is the primary factor in achieving safer sex practices.Citation9–11

As early as 1990, the South African women's health researcher and activist Zena Stein made a plea for HIV prevention methods that women can initiate or control.Citation12 So far, the female condom is the only method that allows women to control protecting themselves and their partners. According to Mantell, Stein and Susser, use of the female condom can empower women, give them a greater sense of self-reliance and autonomy, and enhance dialogue and negotiation with their sexual partners.Citation13

Access to protection has become increasingly urgent as the number and relative proportion of women infected with HIV have risen rapidly, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. This proportion rose from 50% of people living with HIV in 1998 to 59% in 2007.Citation14 Promotion of male condom use for pregnancy prevention has been a success in Africa among young, single women,Citation15 and young single women aged 15–24 are also at high risk of HIV in Africa, due to sexual networking patterns. Although many couples could have benefited from the dual protection of the female condom, they have never heard of it, and even if they have heard of it, they are not able to obtain it.Citation2 Nearly 25 years after its invention, the female condom is still not generally accessible. World production of female condoms remains a very small fraction (0.28%) of all condoms produced and access to this protective device is haphazard and inadequate.Citation16

During the two most recent international conferences on female condoms in 2005Citation17 and 2007Citation18 an overview of female condoms was offered. There are currently three types of female condom on the international market, excluding the so-called panty or bikini kinds, which are designed for the sex industry and mainly used in Latin America. The Female Health Company exclusively manufactures two kinds of female condoms (FC1 and FC2). FC1 is made of polyurethane. FC2 is a newer version and is almost identical to FC1, except its raw material is synthetic latex, which enables a slightly cheaper production processCitation16 and does not make noise when used, a side-effect which some people disliked in FC1.Citation19–21 FC2 received US FDA approval in 2009.Citation22 A third type of female condom, the Reddy condom, is manufactured by Medtech Products in India. It has received a consumer safety mark for distribution in the European Union (EU) and was approved by the Indian Drug Controller in 2003. It has not been bought by the UN Population Fund (UNFPA) and other public donors, because of lack of approval from the World Health Organization (WHO) pre-qualification system. The Reddy condom is sold through the private sector in countries officially recognising its safety.Citation17Citation23 In this article, we discuss the female condoms manufactured by the Female Health Company and distributed by international aid agencies such as UNFPA and other public donors.

This article analyses the roles played by a range of stakeholders – users of the method, providers, the manufacturer, national governments, international development organisations and donors – to understand why the female condom is not more widely accessible and where, predominantly it is being marginalised, using the linkages between acceptability, availability and affordability.

Methodology

We examined the literature published in 2005–2009 on the female condom through a search on Medline, Psych Info and Popline, using “female condom” and “HIV prevention” as keywords. Studies, reviews, reports, policy documents, commentaries, editorials, written opinions and position papers were reviewed and categorised according to acceptability, availability and affordability issues covered. Three earlier reviews were also studied: a review of eight years (1996–2003) of female condom promotion in South Africa and the USA;Citation24 the systematic review of 137 articles from 1996–2004 by the HIV Research Unit, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa;Citation8 and an in-depth study of the introduction of the female condom in 2008, guided by the Harvard School of Public Health.Citation25

Secondly, we analysed the Lancet edition on the “state of the art of HIV prevention”, presented at the International AIDS Conference in Mexico in 2008, written by key international HIV prevention experts.Citation26 We compared the number of references to the female condom in the six articles with the number devoted to male circumcision for HIV prevention which, unlike the female condom, is currently being widely promoted and gaining funding.Citation13

Thirdly, we observed the participation of global public policymakers during sessions at the 2008 International AIDS Conference, including about 50 high-level international and national officers in decision-making positions at multilateral institutions, such as UNAIDS, UNFPA, WHO, European Union and public donor agencies, and their international assistance to AIDS work. For the purpose of this article, this group of decision-makers is designated as “global public policymakers”.

We used an analytical framework developed to assess access to new health technologies in developing countriesCitation25 that takes social, economic, political, and cultural processes into account. The framework looks at three equally important aspects of ensuring accessibility: acceptability, availability and affordability. This allowed us to get a better grip on the variety of barriers and where they were occurring.

Findings

Acceptability

A 1997 review by WHO of more than 40 acceptability studies of the female condom, conducted in 40 different countries around the world, found that 37% to 96% of female condom users rated the product as positive and acceptable.Citation27 The review acknowledged that acceptability may be determined as much by how the technology is introduced as by its physical characteristics. A prerequisite for acceptability appeared to be the education, training, and support that accompanied the introduction of the condom and whether it is sustained.Citation20 In Europe and North America, where the female condom was simply made available in the mid-1990s, women were not automatically interested in using it. The different AIDS context and the easy access to other contraceptives made people less interested in adopting it.Citation20

After 1997, user acceptability studies in developing countries continued. Vijayakumar et al's review of 60 female condom acceptability studies from 1996 to 2004Citation8 concluded that the female condom was an acceptable commodity, and that it should be made accessible quickly. The method has also elicited mixed reactions, especially when it is tried out for the first time, but may become acceptable after further use. Especially after a proper introduction, users appreciate the product. Training in insertion skills, as well as negotiation and communication skills, are important issues for users.Citation6,28,29

“We both have to get used to it. But he doesn't like the male condom, and we do need to protect ourselves. I think practice makes it perfect, so the more I use it, the more I get used to it.”Citation28

“The advantages of the female condom are that, we women, have our own condom, and our partner couldn't say – no, I am not going to use it. If he doesn't want to use it, I use it. What is he going to do? The other advantage is that the female condom gives more pleasure.”Citation21

“The meetings were good, because many things were explained. I have rehearsed again how to insert it correctly in a model resembling the vagina. We also talked about how to introduce it to the partner. I found it very cool.”Citation29

Almost all studies and programmes have concluded that accurate, non-judgemental information from health care providers and media, and training and practice for women/couples, help to make the female condom acceptable to the majority of potential users and women succeed in sustaining its use.Citation10,20,29 People's initial lack of interest can be reversed, negative rumours dispelled, fears alleviated, and awareness that one can have pleasurable sex while being protected can be raised.Citation2,6,8–11,13,19,20,24,25,28–30 Yet, these findings have not been taken seriously by stakeholders at higher levels. The myth that women do not accept and like the female condom persists and continues to be influential.Citation31

The lack of acceptability of female condoms by health care providers has been reported in several studies in South Africa, USA and Kenya.Citation24,25,32 Some providers found themselves without the capacity, support or training to offer female condoms. Others lacked, for example, pelvic models to demonstrate condom use. Others were concerned about likely inconsistency of supply. Health providers lacked not only knowledge and support, but also had their own inhibitions about sexuality, and were not convinced their patients would accept and want female condoms.Citation25 The intricacies of women's bodies were still a forbidden topic among some South African health staff.Citation24 Social ideals about appropriate female sexual behaviour, such as demureness and innocence, increased providers' expectations that women would not be interested in using female condoms. Moreover, female condom programmes have often been targeted only at sex workers, in the belief that only sex workers can take protection into their own hands.Citation15 Targeting sex workers might have led to stigmatisation rather than normalisation of the product.Citation10Citation13 According to a London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and WHO study, the needs of married and cohabiting couples have been neglected, and the barriers to condom adoption by married couples may not be as severe as is often assumed.Citation15 This is confirmed by the Harvard School of Public Health review, which noted that too little information has been directed to male partners and too little effort is made to encourage open communication between partners about protection.Citation25

The media have played a very particular role in reporting on the acceptability of the female condom. In the USA and South Africa, some media have reinforced the myth that women dislike the female condom.Citation6,33–35 Susser found that the US media dismissed the female condom on the assumption that uptake would fail because women have a limited say about their bodies, and would find the product unacceptable.Citation35 Media in general continue to portray the female condom as still “on trial”.Citation13Citation25 At the 2008 International AIDS Conference, 24 years after it was first produced, many participants still perceived it as a novelty.

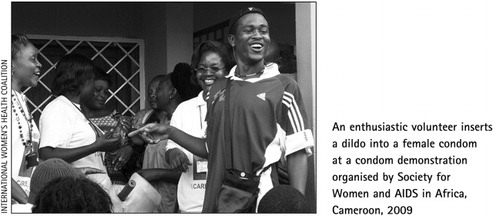

Several political leaders in UgandaCitation36Citation37 and Ministries of Health of African countriesCitation38 have referred to cultural barriers to accepting the female condom.Citation13 In response, leaders of Uganda's women's organisations successfully urged their government to make the method available again, after the government halted distribution in 2007.Citation36 Kibirige, coordinator of the condom unit at the Ugandan Ministry of Health said: “Women – both married and single – have asked us to bring back the female condom.”Citation37 As a result, a new female condom programme was begun. National women's organisations in NamibiaCitation30 and ZimbabweCitation39 have done the same. Other women's groups and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have been less successful, for example in Cameroon (Personal communication Adrienne Germain, Director, International Women's Health Coalition, spring 2007) and Malawi.Citation40

The views of international HIV experts have also influenced the acceptability of the female condom. In the special Lancet issue on HIV prevention, the female condom is mentioned in only one paragraph of one of the six articles,Citation41 which references eight other articles. In contrast, four articles mention male circumcision and reference 44 other articles on male circumcision. Although the benefits of male circumcision for women are less clear than those of female condoms, circumcision programmes are nevertheless being scaled up.Citation42 Moreover, the one short paragraph on female condoms mentions the lack of large-scale epidemiological data on whether the female condom prevents HIV transmission. Yet, a study by Hoke et al in the International Journal of STD & AIDS found that adding female condoms to a male condom distribution system led to decreased STI prevalence, indirectly leading to lower HIV prevalence.Citation43 Secondly, the authors did not ask why nobody ever funded large-scale studies, despite several recommendations to this effect.Citation16,17,23,44 We conclude that the Lancet's international HIV prevention experts seem to have problems accepting the female condom as an effective prevention tool. Lancet editor Richard Horton asked them not only to discuss state of the art HIV prevention, but also “to disrupt the usual axes of power within the AIDS scene”.Citation26 In our view they did not succeed. By barely considering the female condom, they neglected a simple and effective method that could help to challenge gender-based power in HIV prevention, and contribute to women's empowerment in sexual and reproductive health and rights.

What about UNAIDS? At the 2008 International AIDS Conference, Oxfam held a press conference “Failing women, withholding protection. 15 lost years in making the female condom accessible”. A demonstration of around 200 women, mainly representing African constituencies, preceded this event and demanded access to female condoms. One commentator wrote: “Perhaps one of the most impressive displays of women's rights activism at the conference was a rally around an issue that is not typically regarded as generating large, boisterous crowds: female condoms”.Citation45 The day after this demonstration, Michael Bartos, UNAIDS Chief of Prevention Care and Support declared that there was hardly any user demand for the female condom (Personal communication, 7 August 2008) as if the demonstration and press conference were insignificant or had not taken place at all. Notably, UNAIDS has no staff or resources dedicated to supporting female (or male) condom programmes and therefore has not accumulated expertise in this domain. In contrast, UNAIDS and WHO have numerous staff members and resources to work on male circumcision.Citation46 George Brown, former Rockefeller Foundation director and Population Council vice-president, identified a reluctance among bilateral donors to provide funds to scale up the promotion of female condoms.Citation47 Others, such as Oxfam in OxfordCitation23 and the Center for Health and Gender Equity in Washington DCCitation48 confirm similar attitudes among global public policymakers. Global Health Insights researchers Laura Reich and Beth Anne Pratt conclude that commitment, dedication and funding for the female condom as a technology for poor people in poor countries has been too little.Citation25

At global level, public policymakers continue to fund mainly limited distribution projects, perpetuating the view that the female condom is not ready or acceptable for scaling-up.Citation25 There are some positive developments too, however. A new female condom project, Universal Access to Female Condoms (UAFC), was launched in 2009, which provides substantial funding for large-scale female condom programmes and procurement in two countries, Nigeria and Cameroon, supported by SIDA, Danida, Hewlett Foundation and the Netherlands Ministry of Development Cooperation.Citation49

Availability

The introduction of female condoms has been described as successful in three countries in sub-Sahara Africa: Ghana, Zimbabwe and South Africa.Citation50 In all three countries, the success is attributed to the combined efforts of the Female Health Company, which manufactures and sells female condoms; the Female Health Foundation, which is contracted by UNFPA to give technical support to Ministries of Health; UNFPA, who buy and distribute them and support training activities; the Ministry of Health, which ensures transportation to the clinics and trains clinic staff; and Population Services International, a social marketing organisation, which distributes them through various private channels and advertises them in an attractive way. In the mid-1990s, local women and AIDS organisations, such as Women and AIDS Support Network (WASN) in Zimbabwe and the Society for Women and AIDS in Ghana (SWAG) implemented educational programmes for usersCitation39Citation51 and started informing women about the female condom. In 1996, WASN and other women's organisations organised a public march to convince the Ministry of Health and the National AIDS Control Programme to distribute female condoms. The combination of research and advocacy proved to be successful.Citation39 In 2007, however, the momentum was lost in all three countries. Representatives of SWAG and WASN reported in an international workshop that female condom availability was uncertain and unreliable.Citation18 In South Africa, the Thohoyandou Victim Empowerment Programme (TVEP) organised a national workshop in 2008 to call for access to female condoms as a human right.Citation52 However, the existing national strategies for distribution of contraceptives and male condoms in all three countries have failed to integrate female condoms into these programmes. Women in developing countries have especially felt the lack of availability as an injustice:

“I found the female condom quite appropriate and user friendly. Unfortunately, it was not marketed like the male condom was, while many people are dying. That is a criminal offence; we need to promote it again and I believe it will be helpful to some of the women. I would rather have something that is said to be noisy or uncomfortable than get infected with HIV from doing nothing about it.” (Muganwa, Makerere University, Uganda, in an interview with a local newspaper).Citation53

Many people in the field feel frustrated by the failure to scale-up female condom distribution, despite the success of several pilot programmes.Citation3,15,25 Availability could increase demand considerably.Citation3,15,25 According to Friel and other experts, regular stock-outs have been hugely damaging to the availability of this method.Citation54 The FC2 is not yet available on the private market and the Reddy condom is not yet on the public market. The production capacity of the Female Health Company is a serious perennial problem: it cannot meet even the existing worldwide demand, as small as it is (Personal communication, Rino Meijers, consultant, IDA Solutions, June 2008). Their global production is limited to 34.7 million female condoms per year, compared to 12 billion male condoms, in short only a small fraction (0.28%) of all condoms produced.Citation16

In 2005, UNPFA launched a Global Female Condom Initiative, to scale up female condom programming in 23 countries, mainly in Africa.Citation44 It successfully increased the total number of female condoms distributed in Africa, from 4.9 million female condoms in 2005 to 16.5 million by 2008,Citation55 but the annual distribution per country is less than 1 million female condoms. This UNFPA initiative has not been evaluated. According to Frost & Reich, UNFPA decided in 2005 after a global consultation meeting in Baltimore to do away with pilot projects in favour of national distribution strategies,Citation25 but so far they have not been successful in guiding countries to set up a reliable national distribution system.Citation23Citation40 In a meeting at UNFPA in New York in January 2008, several female condom experts argued that distributing so few female condoms per country was ineffective, and that countries needed to ensure scaling-up in a reliable distribution system, preferably integrated into other existing distribution systems.Citation56

We consider that UNFPA's strategy is based on the perception of the female condom as a niche product for a few selected groups of women.Citation23,25,56 We think female condoms should be considered as a public good instead, and should be made available to all sexually active couples who need to protect themselves.

Affordability

Almost everything written on the female condom refers to price barriers.Citation8,12,23,39 From the first international meeting on female condoms in 1993 to the sixth in 2007, global public policymakers such as UNFPA and USAID have considered the price a major barrier to access.Citation18Citation57 Users in developing countries have been unable to purchase female condoms on the private market, because they cost US$2–3 each (FC1).Citation25 This is far too expensive, especially for poor women.

The Female Health Company, which has a monopoly on USFDA and WHO-approved female condoms, sells the majority of its condoms to UNFPA and public donorsCitation16 and sets the price. UNFPA and bilateral donors buy condoms in bulk. For these bulk purchases, UNFPA was only able to negotiate a price 29 times higher than the male condom, i.e. $0.58 per female condom versus $0.02 per male condom.Citation25 Detailed data about the basis for this price are not publicly available. According to Svend Höllensen, the Female Health Company has not exploited economies of scale as a price reduction strategy.Citation16 As a result of low production rates, the price remains high, and the production volume cannot meet demand. Market rationality concerning the female condom is lacking, and this has led to a price monopoly. Why this monopoly and a lack of competition continue to exist deserves a separate study.

One solution to the problem of affordability could have been re-use of the female condom. Already in 1993, Zimbabwean women who were among the first to try out the female condom suggested this idea.Citation19 Sixteen years later, in spite of numerous studies, global consensus regarding re-use was not reached in two WHO consultation meetings in 2000 and 2002. WHO has therefore left the final decision regarding re-use to national governments.Citation58 By remaining ambivalent, WHO has contributed to the non-affordability of the female condom. Sunanda Ray, in a presentation at an international workshop on condoms in 2006, said:

“If you re-use the female condom five times it cuts the cost of a female condom by five. However in the WHO consultation on re-use of female condoms, two thousand women asking for advice on how to re-use the female condoms were defeated at the international level by the recommendations of microbiologists, for whom standards of hygiene were more important than the number of women who got infected with HIV in the meantime. What is needed is a “good enough” solution not a perfect one. This separation of realities also exists in the dissonance between users and health workers, policymakers and programme implementers.”Citation59

Some national governments, like South Africa and Brazil, use their own health budgets to purchase female condoms. Others receive support from donors. The Brazilian government decided for reasons of price to buy female condoms only for sex workers and drug users, and not for the public. As Freire, the Minister for Women's Affairs of Brazil, stated in 2007: “I cannot sell this concept to my government as long as the purchasing price of one female condom is US $ 0.74, the negotiated price with the Female Health Company.”Citation18 Susser reported in 2009 that the Namibian government also did not want to buy female condoms due to the high price.Citation30

Concerted efforts at global and national level and the organised voices of people living with HIV and AIDS have successfully achieved strategic cost reductions on antiretroviral treatment. For the female condom, however, cost reductions have not taken place and the voices of women activists are still not heard. As a result, the cost of the female condom has been caught in a vicious circle – perceived low demand, perceived low acceptability, unwillingness of public policymakers to invest in female condom production, purchase and programmes, stock-outs, high prices and frustrated demand.Citation13,34,54 The result is a stalemate.

Conclusion: stalemate

“The great enemy of truth is very often not the lie – deliberate, contrived, and dishonest – but the myth – persistent, persuasive, and unrealistic.” (John F Kennedy, 1962)

We conclude that female condom programmes have been sabotaged by problematising acceptability among users and by stakeholders failing to create access that would satisfy and increase demand. All stakeholders contribute in different degrees to the marginalisation of the female condom, except women users themselves and some women activists. Collective and synergistic action to increase access to the female condom has not yet been undertaken. On the contrary, according to Frost and Reich, a process of marginalisation of the female condom started shortly after its introduction,Citation25 and has persisted. This is incomprehensible given that:

“The failure of recent trials to show the efficacy of new microbicide candidates and the diaphragm, make the promotion of the female condom as a life-saving intervention more prominent than ever.” (John McConnell, Editor, Lancet Infectious Diseases, 2008)Citation60

References

- American Foundation for AIDS Research. The effectiveness of condoms in preventing HIV transmission. Issue Brief 1. 2005; AMFAR: Washington.

- S Hoffman, JA Smit, J Adams-Skinner. Female condom promotion needed. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 8: 2008; 348.

- L Artz, M Macaluso, I Brill. Effectiveness of an intervention promoting the female condom to patients at sexually transmitted disease clinics. American Journal of Public Health. 90(2): 2000; 237–244.

- AL Fontanet, J Saba, V Chandelying. Protection against sexually transmitted diseases by granting sex workers in Thailand the choice of using the male or female condom: results from a randomized controlled trial. AIDS. 12(14): 1998; 1851–1859.

- PP French, M Latka, EL Gollub. Use-effectiveness of the female versus male condom in preventing sexually transmitted disease in women. Sexual Transmitted Diseases. 30(5): 2003; 433–439.

- EL Gollub. The female condom: tool for women's empowerment. American Journal of Public Health. 90(9): 2000; 1377–1381.

- DW Dowdy, MD Sweat, DR Holtgrave. Country-wide distribution of the nitrile female condom (FC2) in Brazil and South Africa: a cost-effectiveness analysis. AIDS. 20: 2006; 2091–2098.

- G Vijayakumar, Z Mabude, J Smit. A review of female-condom effectiveness: patterns of use and impact on protected sex acts and STI incidence. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 17: 2006; 652–659.

- AL Gray, JA Smit, N Manzini. Systematic review of contraceptive medicines. Does choice make a difference?. 2006; University of Witwatersrand: Johannesberg.

- S Hoffman, J Mantell, T Exner. The future of the female condom. International Family Planning Perspectives. 30(3): 2004; 1–16.

- S Napierala, MS Kang, T Chipato. Female condom uptake and acceptability in Zimbabwe. AIDS Education and Prevention. 20(2): 2008; 121–134.

- ZA Stein. HIV prevention: the need for methods women can use. American Journal Public Health. 80: 1990; 460–462.

- JE Mantell, ZA Stein, I Susser. Women in the time of AIDS: barriers, bargains, and benefits. AIDS Education and Prevention. 20(2): 2008; 91–106.

- UNAIDS/WHO. Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. July. 2008; UNAIDS: Geneva.

- J Cleland, MM Ali, I Shah. Trends in protective behaviour among single vs. married young women in sub-Saharan Africa: the big picture. Reproductive Health Matters. 14(28): 2006; 17–22.

- S Höllensen. Global Marketing: A Decision-Oriented Approach. 2007; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River NJ.

- B Shane. The female condom. Significant potential for STI and pregnancy prevention. Outlook. 22(2): 2006; 1–7.

- Oxfam, Novib. A matter of choice rather than noise. International meeting on the female condom. Oegstgeest, Netherlands, 2007.

- S Ray, M Bassett, C Maposhere. Acceptibility of the female condom in Zimbabwe: positive but male-centred responses. Reproductive Health Matters. 3(5): 1995; 68–79.

- R Parker, RM Barbosa, P Aggleton. Framing the Sexual Subject. The Politics of Gender, Sexuality and Power. 2000; University of California Press: London.

- PR Telles Dias, K Souto, K Page-Shafer. Long-term female condom use among vulnerable populations in Brazil. AIDS and Behavior. 10: 2006; 567–575.

- US FDA. New device approval FC2 female condom. At: <www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/.../ucm155798.htm. >. Accessed 18 February 2010.

- Oxfam International. Failing women, withholding protection. 15 lost years in making the female condom accessible. Oxfam Briefing Paper. Oxford, 2008.

- A Kaler. The future of female controlled barrier methods for HIV prevention: female condoms and lessons learned. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 6(6): 2004; 501–516.

- LJ Frost, MR Reich. Access: How Do Good Health Technologies Get to Poor People in Poor Countries?. 2008; Harvard University Press: Cambridge.

- Lancet. An all-out, unprecedented effort towards HIV prevention – as has been successfully made towards HIV treatment – is imperative. Special issue on HIV prevention. International AIDS Conference, Mexico. August 2008.

- UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction. The Female Condom: A Review. 1997; World Health Organization: Geneva.

- BAM Simons. Over the threshold. Female condom introduction, negotiation and use within heterosexual relationships in Lagos, Nigeria. MA thesis. 2009; University of Amsterdam: Amsterdam.

- KH Choi, C Hoff, SE Gregorich. The efficacy of female condom skills training in HIV risk reduction among women: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Public Health. 98(10): 2008; 1841–1848.

- I Susser. AIDS, Sex, and Culture. Global Politics and Survival in Southern Africa. 2009; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester.

- Nation Nairobi News. Female condoms still out of reach. World Young Women's Christian Association Conference, Nairobi, 2007. At: <www.allafrica.com/stories/printable/200707021747.html>. Accessed 19 November 2009.

- E Mung'ala, N Kilonzo, P Angala. Promoting female condoms in HIV voluntary counselling and testing centres in Kenya. Reproductive Health Matters. 14(28): 2006; 99–103.

- M Latka. Female-initiated barrier methods for the prevention of STI/HIV: Where are we now? Where should we go?. Journal of Urban Health. 78(4): 2001; 571–580.

- A Kaler. Female condoms overlooked in fight against spread of HIV/AIDS. 2004; University of Alberta: Edmonton.

- I Susser. Sexual negotiations in relation to political mobilization: the prevention of HIV in comparative context. AIDS and Behavior. 5(2): 2001; 163–172.

- The Body. Uganda's Ministry of Health to reintroduce female condoms. At: <www.thebody.com./content/news/art50563>. Accessed 19 November 2009.

- IRIN. Ditched female condom makes a comeback. Kampala, 2009. At: <www.plusnews.org>. Accessed 19 November 2009.

- E Musoni. Culture hindering use of female condoms. New Times Rwanda. 17 June. 2007. At: <www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/74839.php. >. Accessed 18 February 2010.

- Osewe G. The female condom in Zimbabwe. The interplay of research, advocacy and government action. A case study, 1999. At: <www.popcouncil.org>. Accessed 18 February 2010.

- Longwe F. Female condoms are here to stay. Film documentary, 2008. At: <www.youtube.com/watch?v=srcMEp_eZog>. Accessed 19 November 2009.

- NS Padian, A Buvé, J Balkus. Biomedical interventions to prevent HIV infection: evidence, challenges, and way forward. Lancet special issue on HIV prevention. August. 2008; International AIDS Conference: Mexico.

- United Nations Interagency Team on Male Circumcision for AIDS Prevention. Country experiences in the scale-up of male circumcision in the Eastern and Southern Africa Region: two years and counting. 2009; IATT: Namibia.

- TH Hoke, PJ Feldblum, K Van Damme. Temporal trends in sexually transmitted infection prevalence and condom use following introduction of the female condom to Madagascar sex workers. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 18: 2007; 461–466.

- PATH/UNFPA. Female condom: a powerful tool for protection. 2006; UNFPA, PATH: Seattle.

- Whipkey K. Women take the streets… and the media center. Mexico, 2008. At: <www.aids2008.com/blog/27>. Accessed 19 November 2009.

- United Nations. Work plan on male circumcision and HIV. Geneva, 2005.

- GF Brown, V Raghavendran, S Walker. Planning for microbicide access in developing countries: lessons from the introduction of contraceptive technologies. 2006; International Partnership for Microbicides: Silverspring.

- Center for Health and Gender Equity. Saving lives now. Female condoms and the role of US foreign aid. Washington DC, 2008.

- Oxfam Novib World Population Foundation IDA Solutions Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Universal access to female condoms. Joint Programme Business Plan 2008–2010. 7 April. 2008; Oxfam Novib: The Hague.

- M Warren, A Philpott. Expanding safer sex options: introducing the female condom into national programmes. Reproductive Health Matters. 11(21): 2003; 130–139.

- D Rogow. In Our Own Hands: SWAA-Ghana Champions the Female Condom. 2006; Population Council and Family Health International: New York.

- Thohoyandou Victim Empowerment Programme. The 2008 Thohoyandou victim empowerment dialogues: universal access to female condoms. A human rights issue. Report of a workshop. Johannesburg, 10–11 September 2008.

- Ajwang J. Women having rough time with Femidom. News Monitor Online Uganda, 2009. At <www.monitor.co.ug/artman/publish/news>. Accessed 19 November 2009.

- Friel P. Review of past action plans and their implementation. Global Consultation on the Female Condom by UNFPA, PATH, Gates Foundation, Hewlett Foundation, DFID. Baltimore, 2005.

- UNFPA. Donor support for contraceptives and condoms for STI/HIV prevention. 2008; UNFPA: New York.

- Oxfam Novib, World Population Foundation, IDA Solutions. You might lose the investment, but win the battle. Report of a study visit to USA. 14–19 January 2008

- WR Finger. The female condoms from research to marketplace. Report of an international meeting. 1997; Family Health International: Arlington.

- WHO. Considerations regarding reuse of the female condom: information update. 10 July. 2002; WHO: Geneva.

- Ray S. Empathy: the missing ingredient. Presented at: Condoms: an international workshop. Meeting Report. International HIV/AIDS Allliance & Reproductive Health Matters. London, 21–23 June 2006.

- J McConnell. The female condom: still an under-used prevention tool. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 8: 2008; 343.