Abstract

Studies suggest that the experiences of unmarried young women seeking abortion in India differ from those of their married counterparts, but the evidence is limited. Research was undertaken among nulliparous young women aged 15–24 who had abortions at the clinics of a leading NGO in Bihar and Jharkhand. Over a 14-month period in 2007–08, 246 married and 549 unmarried young abortion seekers were surveyed and 26 who were unmarried were interviewed in depth. Those who were unmarried were far more likely to report non-consensual sexual relations. As many as 25% of unmarried young women, compared to only 9% of married young women, had had a second trimester abortion. The unmarried were far more likely to report non-consensual sexual relations leading to pregnancy. They were also more likely to report such obstacles to timely abortion as failure to recognise the pregnancy promptly, exclusion from abortion-related decision-making, seeking confidentiality as paramount in selection of abortion facility, unsuccessful previous attempts to terminate the pregnancy, and lack of partner support. After controlling for background factors, findings suggest that unmarried young women who also experienced these obstacles were, compared to married young women, most likely to experience second trimester abortion. Programmes need to take steps to improve access to safe and timely abortion for unmarried young women.

Résumé

Les études semblent indiquer que les expériences des jeunes femmes célibataires souhaitant avorter en Inde diffèrent de celles des femmes mariées, mais les données sont limitées. Des recherches ont été entreprises auprès de jeunes nullipares âgées de 15-24 ans qui avaient avorté dans les dispensaires d'une ONG de premier plan au Bihar et au Jharkhand. Sur une période de 14 mois en 2007–08, l'enquête a porté sur 246 femmes mariées et 549 célibataires souhaitant avorter, alors que 26 célibataires faisaient l'objet d'un entretien approfondi. Les célibataires avaient beaucoup plus de probabilités de faire état de relations sexuelles non consensuelles. Jusqu'à 25% des célibataires, contre seulement 9% des jeunes épouses, avaient avorté au deuxième trimestre. Les célibataires risquaient aussi davantage de notifier des obstacles à un avortement précoce tels que la non-reconnaissance rapide de la grossesse, l'exclusion de la prise de décision liée à l'avortement, la confidentialité comme qualité primordiale dans la sélection d'un centre d'avortement, les tentatives préalables d'interruption de grossesse ayant échoué et le manque de soutien du partenaire. Après contrôle des facteurs circonstanciels, les conclusions suggèrent que les jeunes célibataires qui rencontraient aussi ces obstacles couraient plus de risques que les femmes mariées d'avorter au deuxième trimestre. Les programmes doivent prendre des mesures pour améliorer l'accès des jeunes célibataires à un avortement sûr et précoce.

Resumen

Los estudios indican que las experiencias de mujeres jóvenes solteras que buscan servicios de aborto en India difieren de las de las casadas, pero la evidencia es limitada. Se realizaron investigaciones entre mujeres jóvenes nulíparas, de 15 a 24 años de edad, que tuvieron abortos en clínicas de una de las principales ONG de Bihar y Jharkhand. En un plazo de 14 meses, en 2007–08, 246 jóvenes casadas y 549 solteras que buscaban servicios de aborto fueron encuestadas y 26 de las solteras fueron entrevistadas a profundidad. Entre las solteras, la probabilidad de que informaran relaciones sexuales no consensuales fue mucho mayor. Hasta un 25% de las jóvenes solteras, comparado con sólo el 9% de las jóvenes casadas, habían tenido un aborto en el segundo trimestre. Resultó mucho más probable que las solteras informaran embarazos productos de relaciones sexuales no consensuales. Además, presentaron más probabilidad de mencionar obstáculos a un aborto oportuno como no poder reconocer el embarazo con prontitud, ser excluida de la toma de decisiones relacionadas con el aborto, buscar confidencialidad como algo fundamental en la selección del servicio de aborto, haber fracasado en intentos anteriores de interrumpir el embarazo y no contar con el apoyo de su pareja. Tras controlar por factores de antecedentes, los hallazgos indican que las jóvenes solteras que también afrontaron estos obstáculos, comparadas con las jóvenes casadas, presentaron mayor probabilidad de tener un aborto en el segundo trimestre. Es imperativo que los programas tomen las medidas necesarias para mejorar el acceso a los servicios de aborto seguro y oportuno para las jóvenes solteras.

Pre-marital sexual relations have increasingly been documented in India,Citation1Citation2 and studies suggest that few young people are using condoms or any other contraceptive method consistently, risking unintended pregnancy. A recent study among unmarried college students, for example, found that 8–12% of sexually experienced young women or girlfriends of sexually experienced young men had ever had an unintended pregnancy and all of these pregnancies had been terminated.Citation3

Evidence on the abortion-related experiences of unmarried young women is sparse.Citation4 Several facility-based studies from India have suggested that young and unmarried women constitute significant minorities of all abortion patients,Citation4–10 that young abortion seekers are more vulnerable than adult women seeking abortionCitation4 and that those who are unmarried and young are even more vulnerable than their married counterparts, in that they are more likely to delay seeking an abortion and to go to unqualified providers.Citation11 Few studies, (with one exceptionCitation4) have explored other aspects of the abortion-seeking experience related to being young and unmarried.

We aimed to shed light on the experiences of unmarried young abortion-seekers aged 15–24, compare their experiences with those of their married counterparts, and explore the proximate factors leading to delays in them obtaining abortions into the second trimester. Data were obtained from facilities in two poorly developed neighbouring states in north India with weak health systems, Bihar and Jharkhand. The factors causing delays that we studied – drawn from studies conducted largely among married women – included recognition of pregnancy, decision-making on when and where to seek termination, multiple (unsuccessful) attempts to terminate the pregnancy, fear of disclosure and consequent prioritisation of confidential rather than skilled services, and lack of partner support.Citation4,12–15 While these do not necessarily suggest that these abortions will have been unsafe, the risks of unsafe abortion and abortion-related complications would clearly be heightened.

Background

Although abortion has been legally available in India since 1972, of the roughly 6–7 million estimated abortions per year, just one million occur in authorised facilities by certified providersCitation16, and 8% of all maternal deaths are attributed to unsafe abortion.Citation17

Information about the age and marital status of abortion seekers has come from both community-based and facility-based studies of all abortion seekers. Findings from facility-based studies suggest that 27–30% of all abortion seekers were aged under 25,Citation5Citation6 while in a community-based study in rural Maharashtra, over half of all abortion-seekers were under 25.Citation12 At the same time, several facility-based studies have noted that a significant proportion of all young abortion seekers were unmarried;Citation4,9,11,18,19 one study in Manipur reported that three-quarters of all nulliparous abortion seekers were unmarried.Citation18 Studies comparing abortion-seeking experiences of married and unmarried young women are rare; those that are available focused on the timing of abortion and highlighted that unmarried young women were more likely to experience delays into the second trimester than were married ones.Citation4,5,11,20

Study setting

Socioeconomic indicators are similar for both Bihar and Jharkand. Both states lag behind other Indian states on most development indicators, including access to health services. For example, the two states contain just 116 of the 11,636 institutions approved to provide abortion services. Qualitative studies undertaken in this region underscore the difficulty women face in accessing safe abortion.Citation13Citation21 Moreover, compared to India as a whole, Bihar and Jharkhand report lower literacy rates in young women (43–50% vs. 68% for all-India), larger percentages marrying before age 18 (63–69% vs. 47% for all-India) and a larger proportion of pregnancies in adolescence (25–28% vs. 16% for all-India).

The study was located in clinical settings of the NGO Janani, a DKT International affiliate that operates in both Bihar and Jharkhand and provides a range of reproductive health services through a network of facilities and outreach activities. Its clinics are certified under the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act to provide abortion and each clinic has at least one doctor who is registered to provide abortion. Although Janani charges a nominal fee (at the time of the survey, Rs 199 (US$4) for medical abortion, Rs 399 (US$9) for first trimester surgical abortion and Rs 799 (US$18) for second trimester surgical abortion), its clinics are preferred to government clinics and other private health facilities by large numbers of poor women because they are reliable, confidential, of high quality and there are no hidden costs (e.g. drugs or tests). As a result, Janani is a major provider of abortion services, and conducts a large proportion of all abortions reported in Bihar and Jharkhand.

Data and methods

Although the study was designed to be conducted in 16 of Janani's 23 clinics, recruitment actually took place from only eight, which together accounted for 91% of all adolescent abortion seekers (based in Ara, Gaya, Patna and Purnea, Bihar and Hazaribagh, Jamshedpur, Latehar and Ranchi, Jharkhand). As the remainder reported a relatively small abortion case-load, we were unable to recruit many respondents from them.

The study was undertaken from November 2007 to December 2008 among consenting young women who reported no previous live births. Janani does not obtain information on marital status from its abortion patients, but does collect information on previous pregnancies and births. Hence, all young women aged 24 or younger who had not had a previous birth, irrespective of their marital status, were invited to participate.

Interviewers comprised a mix of non-medical Janani staff and project-recruited staff when Janani was unable to spare someone. Prior to the study, all of them underwent a rigorous five-day training programme that focused on study design and research ethics. There was one interviewer at each clinic over the entire recruitment period, who invited all eligible young women to participate.

The study involved a survey of abortion seekers and in-depth interviews with selected unmarried survey respondents. The survey questionnaire was administered following the abortion at a time and place chosen by the respondent, usually in the clinic prior to discharge. Consent was sought at two points – first, prior to the abortion and again prior to the scheduled interview. Only those who consented at both times were enrolled in the study. Fewer than 1% (six young women) of those who were invited refused to participate.

In the survey interview, marital status was probed. Many of the unmarried young women tried to conceal their status; some even wore the mangalsutra (necklace) typically worn by married women. To obtain accurate responses, questions on marital status were posed towards the middle of the survey interview when the women were more relaxed. At the conclusion of that interview, moreover, all respondents were asked to record their marital status, anonymously, on a form which they then returned to the interviewer in a sealed (but linked) envelope. If the young woman reported that she was unmarried either directly to the interviewer or the sealed envelope, she was defined as unmarried. In addition, a few respondents were purposively selected for an in-depth interview. Those who consented were interviewed at a time and place convenient to them about one week following the survey interivew.

Both the survey and in-depth interviews explored the circumstances of the pregnancy that the young woman had just terminated as well as the abortion experience, including when she had recognised that she was pregnant, when the decision to seek abortion was made and when she had the abortion at Janani. Questions also explored the extent of her participation in the decision to seek abortion, factors considered important in the choice of facility, any previous attempts to terminate the pregnancy, and extent of support from her partner, family members or friends.

Respondents

A total of 795 young women were surveyed, of whom 549 were unmarried and 246 married. In-depth interviews were conducted with 26 randomly selected unmarried survey respondents.

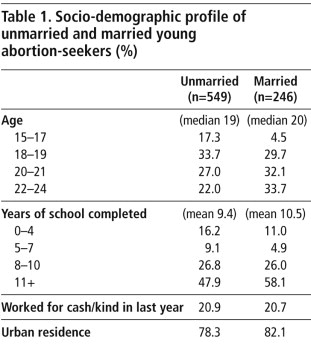

The unmarried were about a year younger than the married (mean age 19 vs. 20) (Table 1 ). Both married and unmarried were generally well-educated; 75% of the unmarried, compared to 84% of the married, had at least eight years of education. The majority in both groups came from urban areas (78–82%), either the city or town in which the facility was located or a neighbouring town. One in five had worked for either cash or kind in the last year.

Man with whom they became pregnant and reason for abortion

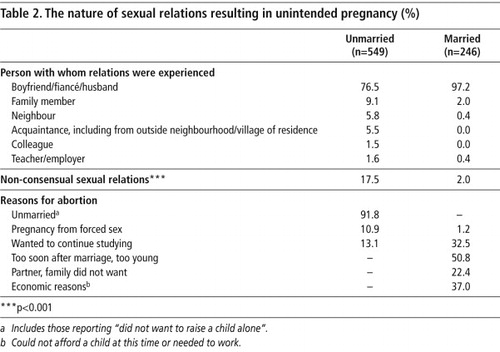

For most young abortion seekers, the sexual relations that resulted in the unintended pregnancy were consensual. The partner with whom the married young women became pregnant was overwhelmingly their husband (97%) and for the unmarried mostly their boyfriend or fiancé (77%). Others with whom they got pregnant, however, included a family member (9% and 2% for the unmarried and married, respectively), or a neighbour, acquaintance, colleague, teacher or employer (14% and 1%, respectively). In all, for 18% of the unmarried and 2% of the married, sexual relations were non-consensual; the partner, in these cases, was largely a family member, neighbour or acquaintance (Table 2 ).

Reasons for having an abortion were also different. The main reason among those who were unmarried was that they were unmarried (92%), the pregnancy had resulted from a forced encounter (11%), or that they wished to continue their education (13%). Among the married, the leading reason was that they were too young or the pregnancy had come too soon after marriage (51%), economic reasons (37%), desire to complete their education (33%), or that their husband or family did not want a child at that time (22%) (Table 2).

Disadvantages and delays in obtaining abortion

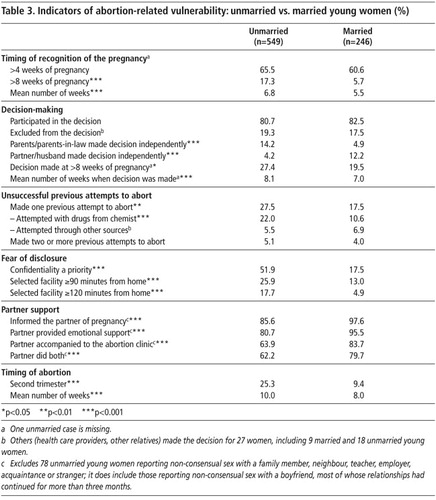

Table 3 shows the factors that caused delays and difficulties in seeking abortion and in many cases led to abortion being delayed, often into the second trimester. In this, unmarried young women were far more disadvantaged than those who were married on most indicators. Thus, one-quarter of unmarried young women, compared to 9% of married, experienced delays in obtaining an abortion beyond 12 weeks of pregnancy.

The first delay was in realising they were pregnant. While differences were narrow, unmarried young women took longer than the married to recognise the pregnancy: 17% of unmarried young women, compared to 6% of the married ones, only realised after they had missed two menstrual cycles, i.e. at nine or more weeks of pregnancy.

“When my periods stopped, I started thinking that something was wrong. But when I observed that my body shape was also changing, then I felt sure that I was pregnant. And then I had a urine test.” (ID A, 20 years, studying, Bihar)

“As it was the first time, we did not know anything. My periods stopped in October for the first time and I thought of waiting and observing for a month and then again when I did not have it in November, I was in doubt but thought of waiting for another month and then get a check- up done. Then I was completely sure that I was pregnant.” (ID B,18 years, studying, Jharkhand)

“I started to feel a vomiting sensation. I had no idea that when you conceive a child, your periods stop. I started vomiting and my mother asked me when I had my last period. I told her that I had not had my period for the last three months. Then my mother asked me what had happened to me and what I had done.” (ID C, 18 years, not studying or working, Bihar)

The decision to terminate the pregnancy

Respondents were asked whether they had been involved in the decision whether to seek abortion, either independently or along with their partner or anyone else, and how long after they realised they were pregnant the decision was made. Over 80% of all respondents had participated in the decision to seek an abortion, and differences between the unmarried and married were insignificant in this regard. Among the unmarried, however, 14% reported that their parents had made the decision on their own, and 4% that their partner had done so. Among the married, 5% reported that their parents or parents-in-law had made the decision on their own, and 12% that their husband had done so.

“We took this decision (to abort) together.” (ID D,19 years, currently working, Bihar)

“My parents took the decision that I should undergo abortion. I was not asked but even I wanted the abortion.” (ID E, 17 years, studying, Bihar)

“My sister told me that I must get the abortion done or else time will pass, our father will get to know and then there will be problems. So I agreed.” (ID F, 18 years, studying, Bihar)

“My whole family took this decision – my mother, maternal uncle and aunt.” (ID G, 15 years, studying, Bihar)

Previous unsuccessful attempts to terminate the pregnancy

A significant proportion of respondents had made at least one unsuccessful attempt to terminate the pregnancy before arriving at the Janani clinic. Significantly more unmarried than married young abortion seekers had done so at least once (28% vs. 18%) and a small proportion (4–5%) two or more times. Unsuccessful attempts had largely involved oral medication obtained from a chemist (22% of unmarried and 11% of married young women). Although information on the exact medication obtained was not collected, other studies in these states have noted that abortion-seekers frequently obtain the medical abortion drugs mifepristone and/or misoprostol without a prescription or knowledge of the correct dosage, as well as a variety of Ayurvedic and other drugs.Citation22

“I was late in coming to Surya because I was trying something or the other at home to get rid of this [pregnancy]. I tried homeopathic medicines but nothing happened with that… It was to be taken for three days; I suppose its name was Mensolex… I didn't get it myself; my boyfriend got that for me. But nothing happened with that.” (ID A, 20 years, studying, Bihar)

“My father got three tablets, each cost Rs. 300… I had all of them together… I don't know where my father got this medicine from – a doctor or someone else. My mother gave me the medicine. She asked me to have it and said that this will end my problem. But nothing happened.” (ID E, 17 years, not studying or working, Bihar)

“When my periods did not occur, I told him (partner). I did not wish to keep the child, so he brought some medicine from the chemist that I took but nothing happened.” (ID H, 19 years, not studying or working, Jharkhand)

Effect of fear of disclosure on clinic selection

We asked respondents the main factors that influenced the choice and location of the abortion facility or provider, in terms of travel time from their home. Fear of disclosure was frequently reported by the unmarried young women in the in-depth interviews.

“My entire family thinks that I am a good girl and I did not want to take a wrong step. I was very scared. I thought if they got to know that if I was pregnant, then they would scold me.” (ID I, 18 years, studying, Jharkhand)

Extent of partner support

In assessing the extent of partner support, we exclude those unmarried young women who reported that their pregnancy had resulted from non-consensual sex with anyone other than a boyfriend. Even so, marital status made a significant difference to whether the young women had informed their partner about the pregnancy, whether the partner provided emotional support once informed, and whether the partner had accompanied her to the facility.

As many as 86% of unmarried young women felt comfortable enough to inform their partner about the pregnancy compared to almost all of the married (98%). Partners typically provided emotional support; however, once again, the unmarried were less likely than the married to so report (81% and 96%, respectively). While fewer respondents reported that the partner had accompanied them to the Janani facility on the day of abortion, once again, fewer unmarried than married young women so reported (64% and 84%, respectively). Finally, 62% of the unmarried compared to 80% of the married reported that the partner had both provided emotional support and had accompanied her to the facility. The in-depth interviews with unmarried young women reveal these mixed experiences.

“He (boyfriend) asked me not to worry. He helped me at every step. He supported me a lot. He paid the money for me.” (ID B, 18 years, studying, Jharkhand)

“He (boyfriend) said that we should go for a check-up to Patna. He told me not to feel scared and he supported me. He paid the money needed for the abortion.” (ID J, 18 years, studying, Bihar)

“I did this (abortion) because when I told this thing to that boy, he bluntly refused and I started worrying about who would give a name to this child. And I thought that abortion was the only option I was left with. He (boyfriend) refused to accept the pregnancy and did not support me. Then she (a friend) took me to the clinic”. (ID I, 18 years, studying, Jharkhand)

“He (boyfriend) asked me to get the abortion done. He did not give any money to me nor did he help me in any way. My sister's husband gave me the money that was spent here”. (ID K, 15 years, working, Jharkhand)

Influence of marital status and other factors in delaying abortion

Logistic regression analyses were performed that explored the association between marital status and delay in obtaining abortion, on the one hand, and each of the factors we thought might lead to abortion being delayed, on the other, controlling for the potential confounding factors of age, education, work status and rural–urban residence. Findings show that unmarried young women were significantly more likely than their married counterparts to have undergone a second trimester abortion at Janani. They were also significantly more likely to have considered confidentiality a leading factor in the choice of abortion facility, opted for a distant facility, made at least one unsuccessful attempt to abort, and lacked partner support.

In contrast, once socio-demographic factors were controlled for, marital status was not associated with delayed recognition of the pregnancy into the second month of pregnancy or later, or with whether or not the young woman participated in the decisions related to abortion (data not shown).

Several socio-demographic factors were also significantly associated with disadvantages and delays related to abortion. Younger, less educated and/or rural women were significantly more likely than others to have delayed the decision to terminate the pregnancy, to lack partner support and experience second trimester abortion, as well as with young women's participation in the decision to seek abortion, the importance of confidentiality and selection of a distant facility for abortion.

We carried out individual logistic regression analyses to assess how the interaction between being unmarried and reporting each of the experiences expected to lead to abortion being delayed, affected whether or not the abortion took place in the second trimester, relative to the married young women. Those factors were: recognised pregnancy in second month or later (had two or more missed periods), excluded from abortion decision-making, took decision for abortion after second month of pregnancy, considered confidentiality important in determining facility, selected a facility more than two hours from home, had made previous unsuccessful attempts to terminate this pregnancy, and lacked partner support. We excluded from the analysis the timing of decision-making as it was closely correlated with the timing of abortion. Confounding factors, such as age, education, work status and rural–urban residence were controlled for.

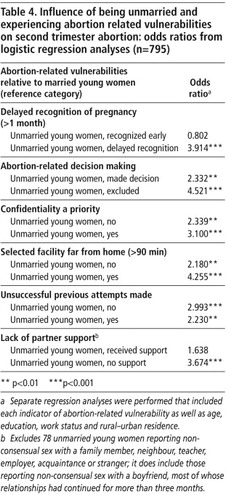

This analysis (Table 4 ) suggests that being unmarried heightened the risk of second trimester abortion irrespective of whether other indicators of vulnerability were experienced. For example, compared to married young women, even unmarried young women who participated in abortion-related decision-making, who did not consider confidentiality to be a priority, who opted for a facility relatively close to home, and who had made no previous attempts to terminate the pregnancy, were significantly more likely than married young women (the reference category) to undergo second trimester abortion (odds ratios ranging from of 2.18–2.99). Unmarried young women who recognised the pregnancy within eight weeks and those who received partner support were, in contrast, about as likely as married young women to undergo second trimester abortion (odds ratios of 0.80 and 1.64, respectively).

Unmarried young women who reported each of the experiences underlying delayed abortion fared far worse. They were, for example, three to five times more likely than married young women to undergo second trimester abortion if they failed to recognise pregnancy by the second month (odds ratio 3.9), if they were excluded from decision-making (odds ratio 4.5), if they considered confidentiality important (3.1), if they opted for a distant facility (odds ratio 4.3), if they made previous unsuccessful attempts to terminate the pregnancy (odds ratio 2.2) and, among those whose relationship was consensual or who experienced non-consensual sex with a boyfriend, if they did not have partner support (odds ratio 3.7), even after controlling for the effects of age, education, rural–urban residence and work status.

Findings confirm that being unmarried itself is a risk factor, but that both being unmarried and experiencing proximate factors clearly exacerbated the risk of experiencing second trimester abortion.

Limitations

We did a facility-based study because community-based studies in India have failed to provide reliable information on abortion seeking among the unmarried. This means findings cannot be generalised to all young abortion seekers. Despite the fact that educational attainment and work status among young abortion-seekers were not significantly different from urban young women in these states more generally, it is likely that the poorest, who were unable to pay for an abortion, were excluded. Moreover, the study would also have excluded young women who successfully aborted by taking mifepristone and/or misoprostol obtained from a chemist shop, or who may have obtained abortion from an untrained provider or, indeed, may have been unsuccessful in terminating the pregnancy and carried it to term. Second, the study does not shed light on abortion-related complications and morbidity. Third, despite the rapport our interviewers were able to build with respondents and the opportunity to report marital status anonymously, some unmarried young women may have concealed their marital status, resulting in some blurring of distinctions between the married and the unmarried. Finally, as our study focuses on young women with no previous births, the findings are not representative of abortion-seekers more generally.

Discussion

Findings highlight that the experience of young women seeking to terminate their first pregnancy varied considerably depending on their marital status. Unmarried young women were more likely than married ones to delay termination of pregnancy, even when socio-demographic factors were controlled for. They were also more likely to experience obstacles that delayed timely abortion-seeking relative to married young women; these obstacles included delayed recognition of pregnancy, lack of partner support, exclusion from decision-making, fear of disclosure and unsuccessful previous attempts to terminate the pregnancy. Moreover, the narratives of the unmarried young women showed how poorly informed they were about the signs and symptoms of pregnancy. Indeed, while being unmarried posed a significant obstacle to early abortion, the combination of being unmarried and experiencing any of these obstacles made unmarried young women three to four times more likely than married ones to undergo a second trimester abortion. The fact that married young women had comparatively few second trimester abortions highlights that it was being unmarried, not being young, that inhibited access to timely abortion. Thus, measures are needed at programme level that facilitate more timely access to abortion for unmarried young women.

Findings highlight the need to provide all young women in adolescence with sound reproductive and sexual health education and information about where they can access contraception when they become sexually active, so that they can protect themselves from unintended pregnancies and sexual health problems. This education should include the signs and symptoms of pregnancy, the importance of early recognition of pregnancy, and their legal right to obtain abortion services. It is important that young men are sensitised about gender roles, ensuring safer sex and the importance of supporting their partner in case of unintended pregnancy. There exist a number of public and NGO-sector life skills and sexuality education programmes, including the Adolescence Education Programme (AEP)Citation24 for school-going adolescents that provide an ideal forum through which such information and efforts to change gender role attitudes can be imparted.

At the health system level, the National Rural Health Mission's Reproductive and Child Health programme has acknowledged the need to address the needs of young peopleCitation25 in its Adolescent Reproductive and Sexual Health Strategy.Citation26 Our findings emphasise the need to implement these commitments. Youth-centred services are needed that are sensitive to the realities of pre-marital sex, including sexual abuse by adults and sexual coercion by peers, unintended pregnancy and the need for abortion among the young, both married and unmarried. Providers must be trained to understand the law with regard to the rights of unmarried young women to secure a safe abortion and the right to obtain abortion confidentially. Efforts must also be made to ensure that providers do not stigmatise the unmarried, that they maintain their confidentiality and that they provide sensitive counselling as required and non-judgemental services. Indeed, our findings highlight the need to recognise unmarried young women as a highly vulnerable group and ensure the realisation of their right to obtain safe abortion services in a more timely manner.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by a grant to the Population Council from the Hewlett Foundation and a grant to the Consortium for Comprehensive Abortion Care from the Packard Foundation and the Swedish International Development Agency. Their support is gratefully acknowledged. We are grateful to Rajib Acharya, KG Santhya, Iqbal Shah and Ina Warriner for valuable comments and suggestions; to MA Jose and Komal Saxena for support in preparing the paper and to Anupa Burman, Rakhi Burman, Preeti Verma and our investigator team for their sensitive and sincere efforts at eliciting information on these difficult topics. We would also like to record our deep appreciation to our young study participants, who so willingly gave us their time and shared their personal experiences with us.

Notes

* Percentages were almost identical when restricted to those for whom the Janani clinic was the first and only facility visited, for the unmarried and married young women as regards the importance of confidentiality and the facility being far from home (data not shown).

References

- International Institute for Population Sciences, Population Council. Youth in India: Situation and Needs 2006–2007. 2010; IIPS: Mumbai.

- SJ Jejeebhoy, MP Sebastian. Actions that protect: promoting sexual and reproductive health and choice among young people in India. SJ Jejeebhoy. Looking Back Looking Forward: A Profile of Sexual and Reproductive Health in India. 2004; Rawat Publications: Jaipur, 138–168.

- R Sujay. Premarital sexual behaviour amongst unmarried college students of Gujarat, India. Health and Population Innovation Fellowship Programme Working Paper No.9. 2009; Population Council: New Delhi.

- B Ganatra. Abortion research in India: what we know and what we need to know. R Ramasubban, S Jejeebhoy. Women's Reproductive Health in India. 2000; Rawat Publications: Jaipur, 186–235.

- S Chhabra, N Gupte, A Mehta. MTP and concurrent contraceptive adoption in rural India. Studies in Family Planning. 19(4): 1988; 244–247.

- ML Solapurkar, RN Sangam. Has the MTP Act in India proved beneficial?. Journal of Family Welfare. 31(3): 1985; 46–52.

- BS Dhall, PD Harvey. Characteristics of first trimester abortion patients at an urban Indian clinic. Studies in Family Planning. 15(2): 1984; 93–97.

- U Rao, K Rao. Abortions among adolescents in rural areas. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of India. 40(6): 1990; 739–741.

- V Salvi, KR Damania, SN Daftary. MTPs in Indian adolescents. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of India. 41(1): 1991; 33–37.

- Government of India. Family Welfare Programme in India: Year Book, 1994–95. 1996; Ministry of Health and Family Welfare: New Delhi.

- R Aras, NP Pai, SG Jain. Termination of pregnancy in adolescents. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine. 33(3): 1987; 120–124.

- B Ganatra, S Hirve. Induced abortions among adolescent women in rural Maharashtra. Reproductive Health Matters. 10(19): 2002; 76–85.

- L Barnes. Abortion options for rural women: case studies from the villages of Bokaro district, Jharkhand. Working paper. Abortion Assessment Project – India. CEHAT/Healthwatch. 2003; Chintanakshar Grafics: Mumbai.

- KG Santhya, S Verma. Induced abortion. SJ Jejeebhoy. Looking Back, Looking Forward: A Profile of Sexual and Reproductive Health in India. 2004; Rawat Publications: Jaipur, 88–104.

- CV Sowmini. Delay in seeking care and health outcomes for young abortion seekers. Report. Small Grant Programme on Gender and Social Issues in Reproductive Health Research. 2005; Achutha Menon Centre for Health Science Studies, Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute for Medical Science and Technology: Trivandrum.

- R Chhabra, SC Nuna. Abortion in India: An Overview. 1994; Ford Foundation: New Delhi.

- Registrar General, India. Maternal mortality in India: 1997–2003. Trends, causes and risk factors. Sample Registration System. 2006; RGI in collaboration with Centre for Global Health Research, University of Toronto: New Delhi.

- IT Devi, BS Akoijam, N Nabakishore. Characteristics of primigravid women seeking abortion services at a referral center, Manipur. Indian Journal of Community Medicine. 32(3): 2007; 175–177.

- S Trikha. Abortion scenario of adolescents in a north Indian city: evidence from a recent study. Indian Journal of Community Medicine. 26(1): 2001

- S Dalvie. Second trimester abortions in India. Reproductive Health Matters. 16(31 Suppl): 2008; 37–45.

- A Barua, H Apte. Quality of abortion care: perspectives of clients and providers in Jharkhand. Economic & Political Weekly. 42(48): 2007; 71–80.

- B Ganatra, V Manning, PS Pallipamulla. Availability of medical abortion pills and the role of chemists: a study from Bihar and Jharkhand, India. Reproductive Health Matters. 13(26): 2005; 65–74.

- S Kalyanwala, AJF Zavier, SJ Jejeebhoy. Unintended pregnancy among unmarried adolescents: factors influencing second trimester abortion. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2010. (forthcoming).

- Ministry of Human Resource Development National AIDS Control Society United Nations Children's Fund. Adolescence Education: National Framework and State Action Plan (2005–06). 2005; MOHRD, NACO, UNICEF: New Delhi.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Reproductive and Child Health Phase II: National Programme Implementation Plan. 2005; MOHFW, Government of India: New Delhi.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Implementation Guide on Reproductive and Child Health Phase II: Adolescent Reproductive and Sexual Health Strategy for State and District Programme Managers. 2006; MOHFW, Government of India: New Delhi.