Abstract

Abstract

This paper reports on an evaluation of a domestic violence intervention in the maternity and sexual health services of a UK hospital. The intervention encompassed guidelines, staff training, inclusion of routine enquiry for domestic violence with all patients, and referral of women disclosing violence to an on-site advocacy service. An “assumption querying” approach was applied to evaluate the intervention. Programmatic assumptions were identified and tested using interviews with service providers and patients, review of patient records, and pre- and post-training questionnaires. Domestic violence training resulted in changes in health professionals' knowledge and practice in the short-term, but universal routine enquiry was not achieved even in a context of organisational support, guidelines, training and advocacy. Potential and actual harm occurred, including breaches of confidentiality and failure to document evidence, limiting women's ability to access civil and legal remedies. Advocacy support led to positive outcomes for many women, as long as support to maintain positive changes, whether women stayed with or left the violent partner, continued to be given. Maternity and sexual health services were found to be opportune points of intervention for domestic violence services that combine routine enquiry by clinicians, support after disclosure and attention to harm reduction.

Résumé

Cet article décrit l'évaluation d'une intervention en matière de violence domestique dans les services de santé génésique et de maternité d'un hôpital britannique. L'intervention comportait des directives, la formation du personnel, une enquête systématique auprès de toutes les patientes sur la violence domestique et l'aiguillage des femmes révélant des violences vers un service de sensibilisation sur place. L'intervention a été évaluée avec une approche de « questionnement des postulats ». On a identifié et testé les postulats des programmes par des entretiens avec les prestataires de services et les patientes, l'examen des dossiers des patientes et des questionnaires avant et après la formation. La formation sur la violence domestique a changé à court terme les connaissances et la pratique des professionnels de santé, mais n'a pas réussi à les inciter à questionner systématiquement toutes les patientes, même dans un contexte de soutien organisationnel, de directives, de formation et de sensibilisation. On a constaté des préjudices potentiels et réels, notamment des violations de la confidentialité et l'incapacité à réunir des preuves, limitant ainsi la possibilité des femmes d'avoir accès à des réparations civiles et juridiques. Le soutien à la sensibilisation a eu des résultats positifs pour beaucoup de femmes, tant que le soutien s'est poursuivi pour maintenir des changements positifs, que les femmes restent ou non avec le partenaire violent. Les services de santé génésique et de maternité se sont révélés des points précieux d'intervention pour les services de violence domestique car ils associent l'enquête systématique des cliniciens, le soutien après la révélation et l'attention à la réduction des risques.

Resumen

Este artículo resume la evaluación de una intervención relacionada con la violencia doméstica en los servicios de salud materna y sexual de un hospital del Reino Unido. La intervención comprendió guías, capacitación del personal, indagación rutinaria de todas las pacientes respecto a la violencia doméstica y referencia de las que denunciaron violencia a un servicio de promoción y defensa in situ. Se aplicó un enfoque de “investigación de suposiciones” para evaluar la intervención. Las suposiciones programáticas fueron identificadas y probadas utilizando entrevistas con profesionales de la salud y pacientes, revisión de los expedientes médicos y cuestionarios pre- y post-capacitación. La capacitación en violencia doméstica produjo cambios en los conocimientos y las prácticas de los profesionales de la salud a corto plazo, pero no se logró establecer una rutina de indagación universal, ni tan siquiera en un contexto con apoyo organizacional, guías, capacitación y promoción y defensa. Ocurrieron daños posibles y reales, como violación de confidencialidad e incumplimiento de documentar la evidencia; éste último limitó la capacidad de las mujeres para acceder remedios civiles y jurídicos. El apoyo de promoción y defensa llevó a resultados positivos para muchas mujeres, siempre y cuando se les continuara brindando apoyo para mantener cambios positivos, independientemente de que la mujer permaneciera con su pareja violenta o la dejara. Se concluyó que los servicios de salud materna y sexual son puntos oportunos de intervención para los servicios contra la violencia doméstica, que combinan la indagación rutinaria por parte del personal de salud, apoyo después de confirmada la violencia y atención a la reducción de daños.

Domestic violence, defined here as any behaviour within an intimate relationship that causes physical, psychological or sexual harm to those in the relationship, is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in women.Citation1 Population-based studies from around the world have established that domestic violence, including violence in pregnancy, is highly prevalent.Citation2 In response to this widespread public health issue, the WHO has identified violence against women as an important issue for health care services and many health professional governing bodies are encouraging their members to take actions to actively identify those at risk, and within multi-sectoral strategies to respond to abused women using their services.Citation3

Debates about the best way to identify and support abused women, whilst being mindful of the potential to do harm, continue to dominate the policy and research agenda.Citation4 Systematic reviews report a lack of robust evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of health sector interventions involving screening for domestic violence. One US randomised, controlled trial demonstrated the effectiveness of a community-based advocacy intervention, offering advice and practical support to women, in reducing the levels of violence and improving social support and quality of life.Citation5 However, it is difficult to generalise these findings to abused women attending health services, since the intervention was delivered to women who had already left their abuser and actively sought help. Little is known about advocacy interventions for abused women using health services who are still in the relationship. Although universal screening for domestic violence is widely advocated by some health professional bodiesCitation3 and has documented benefits,Citation6 it can be difficult to implement in clinical practice. Furthermore, such initiatives are not without risks and their implementation requires careful evaluation.

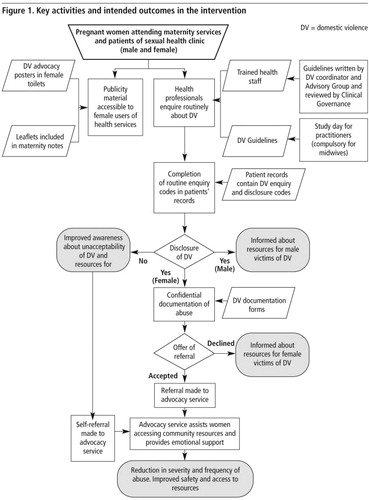

This article presents findings from a two-year evaluation of an intervention in the maternity and sexual health services of a UK hospital, using an “assumption querying” framework. The intervention involved the introduction of domestic violence clinical guidelines, a rolling programme of one-day domestic violence training (June 2005 and September 2007) for health professionals, to increase their knowledge of domestic violence and its impacts and to enable them to conduct routine enquiry for and document abuse and refer women who disclosed abuse to a contracted on-site domestic violence advocacy service (MOZAIC Women's Wellbeing Project, provided by a community organisation). Training was delivered by a specialist domestic violence trainer employed by the hospital and co-facilitated by a midwife. A combination of didactic methods, group exercises, role play and watching a DVD of routine enquiry was used. Health professionals received the training pack containing information and resources which were also available in their clinics. The advocacy intervention utilised a “woman-centred approach” that built on women's own analysis of their situation and the risks they perceived of pursuing different options, in order to support and accommodate their changing needs.Citation7 Advocates assisted women with obtaining a range of community resources. Female members of staff in the hospital experiencing domestic violence were also able to use the advocacy service. Male patients from the sexual health clinic who disclosed domestic violence were offered information about services for male victims and perpetrators of domestic violence.

Methods

The study received ethical approval from St. Thomas' NHS Hospital Ethics Committee in December 2004. We chose a “theory of change” approach as it offered a method of assessing in a systematic and cumulative way the links between activities, outcomes and context. The approach has three stages: articulating with stakeholders the assumptions made within the programme as to how they expect the intervention to change behaviour and outcomes; measuring programmatic activities and the intended outcomes; and analysing and interpreting results, including the implications for adjusting the theory and allocation of resources.Citation8Citation9 Further details of the technique usedCitation10 can be found in the full report.Citation11 Findings from the examination of the following key assumptions about the programme in the two clinics are described in this paper:

| • | Training will help health staff to implement routine enquiry for domestic violence. | ||||

| • | Implementation of a programme of routine enquiry plus on-site support after disclosure can improve detection of domestic violence. | ||||

| • | Maternity and sexual health services are early points of intervention to reduce domestic violence. | ||||

| • | Women who receive support from a domestic violence advocacy service are able to improve their personal situation. | ||||

| • | Routine enquiry about violence and advocacy will not result in harm. | ||||

shows the key stages in the intervention process and intended outcomes.

Qualitative interviews with service users and providers

Purposive sampling was employed to select health professionals and service users from the maternity and sexual health services for interview.Citation12 Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 34 women 1–22 months after they received support from the domestic violence advocacy service, to explore their encounters with the health professionals and the advocacy service. Women were selected according to clinical setting, living with abuser or not at the time of referral advocacy, length of abuse, pregnant or not, immigration status, access to their own money, ethnic origin and first language (English or Spanish). Three hospital staff who used the advocacy service were also amongst those interviewed. The characteristics of the women (details in the full report) are a good reflection of the 156 patients who used the advocacy service, who were mostly young women in their 30s, British nationals and members of an ethic minority group.Citation11

Semi-structured interviews (8 midwives and 11 sexual health professionals) and six focus group discussions (19 midwives and 6 sexual health professionals) were conducted to explore components of training that were most useful in clinical practice, and the effect of training on skills, comfort and confidence in the identification and management of domestic violence. Participants were selected according to clinical setting (maternity or sexual health), professional group (doctors, nurses, midwives, health advisors), gender, and time elapsed since training (3 months vs. 6+ months).

Review of patient records

A review of patient records in maternity and sexual health for January 2007 was undertaken to determine the rate of routine enquiry for and detection of domestic violence after health professionals had received training. By January 2007, 201 (65%) midwives and 32 (58%) sexual health professionals had received domestic violence training and were working in the two clinical services. Maternity records were reviewed for 487 (98%) of the 501 women who gave birth in January 2007. A total of 915 patients attended the sexual health clinic in January 2007. However, of the 879 records available for audit, only 644 (73%) contained the domestic violence code and were analysed.

In order to examine coverage of routine enquiry over one year in the maternity service, comparative data were available from a review of maternity records from a different studyCitation13 in January–March 2006, when 110 midwives in the maternity service (50%) had already received training in routine enquiry. No such comparative data were available for the sexual health clinic.

Pre- and post-training questionnaires: health professionals

Pre- and post-training questionnaires were administered to health professionals from the maternity and sexual health services when they attended domestic violence training. A researcher invited them to self-complete a questionnaire just before training commenced; most responded. An immediate post-training questionnaire was also administered, completed by almost all staff. Six-month post-training questionnaires were posted to staff who had attended training; only about a quarter responded. Details of these questionnaires and results have been published elsewhere.Citation11Citation14

Analysis

Data from the qualitative interviews were transcribed and stored in Atlas Ti Version 5.2. Each interview was coded by the researcher. Content analysis was used to identify key themes that were examined in relation to the assumptions underpinning the intervention.Citation12 Data from the review of patient records and pre- and post-training questionnaires were stored in SPSS Version 14. Separate analysis was conducted for each audit and descriptive statistics and measures of association were used.

Findings

• Assumption 1: Training will help health staff to implement routine enquiry for domestic violence.

It is often assumed that health professional behaviours will change if they attend training, but the effectiveness of any training depends on the recipients and the training itself. Pre-training questionnaires indicated that 94 (55%) maternity and 33 (92%) sexual health professionals had no prior domestic violence training. Immediately post-training, 174 (82%) maternity and 38 (95%) sexual health professionals reported that their knowledge of domestic violence had improved very much or quite a lot. However, in the six-month post-training questionnaire, 43 of the 56 midwives who responded reported problems such as the presence of partners or relatives during consultations, language barriers, time constraints in busy clinics, and some women's reluctance to trust health professionals. These findings were also reflected in the interviews and focus group discussions with midwives.

Although some health professionals were positive about the effect of training on their ability to enquire about domestic violence, others were more reticent. Midwife 1, for example, only felt “a little bit confident about broaching the subject with women” while Midwife 2 felt unable to ask the husband to leave and couldn't think of what to say as to why she wanted to speak to the woman on her own. Health professionals brought different levels of experience and knowledge to the training, and this needed to be taken into account in designing the training programme. Some midwives reported avoiding direct approaches to routine enquiry, for example, asking “Is everything all right at home?” without specific follow-up questions. At times selective rather than routine enquiry for domestic violence was still practised as staff sought an opportune moment.

“I came away from the training not really feeling confident about asking the questions… Although we did a role play and it was explained to us, it felt like it was left to the end, and that domestic violence awareness took up most of the day and the actual training around asking the questions was left to the last.” (Sexual health, Senior nurse 1)

“I would probably say honestly that I ask about 40–50% of the women that I book… because you think, ok, well, I won't ask this time but the next time I'll feel a bit more up to it. I think we ask so many things at the booking interview and sometimes there's a natural progression and you can ask them, sometimes it's just completely out of the blue and it doesn't feel right.” (Midwife 3)

• Assumption 2: Implementation of a programme of routine enquiry plus on-site support after disclosure can improve detection of domestic violence.

The policy prior to the intervention involved reacting to spontaneous disclosure of violence plus selective questioning when signs of abuse were apparent. The design of the intervention was predicated on the notion that routine enquiry by staff, in a context where they could refer women to an on-site domestic violence advocacy service, would be more effective in detecting domestic violence.

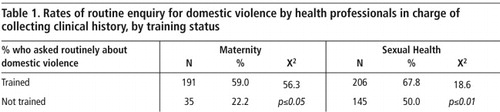

This assumption could not be fully tested in the absence of reliable data on pre-intervention disclosure rates. However, the audits of maternity records conducted in January–March 2006 and January 2007 indicate that the rate of routine enquiry for domestic violence increased three-fold from 15% (170 out of 1,133 women) in the first year of training to 47% (229 out of 487 women) in the second year (RR 3.09; CI 2.61–3.65). The rate of routine enquiry for domestic violence in the sexual health clinic was 58% (374 of 644 patients) according to the January 2007 record audit. Female patients were significantly more likely to be asked about domestic violence than male patients [204 (68%) vs. 169 (49%); 12=21.77, df=1, p≤0.01]. Some sexual health professionals were not always comfortable asking heterosexual men about domestic violence.

“…so my main asking of men has probably been around [the] gay men's clinic as it happens, and it's been fine. The only time it's been more difficult was maybe with straight guys… who don't sort of understand quite why you're asking.” (Sexual health, Senior nurse 2)

Disclosure of domestic violence did not only arise from routine enquiry. In the maternity service, clinical signs such as bruising on the abdomen, depression or a public altercation between the woman and her partner alerted health professionals to the possibility of abuse, which prompted them to ask about it. Confidence and sensitivity were needed in situations where women were reluctant to disclose abuse.

“…I was in tears and she noticed the bruises on my arm… and she started questioning me and I said to her that I was fine and she said ‘No, you can talk to me’ and then she dug and dug and then I opened up to her.” (Maternity service user 1, 31 yrs, 13 months post-intervention)

• Assumption 3: Maternity and sexual health services are early points of intervention to reduce domestic violence.

Some domestic abuse may start during pregnancyCitation15 and at the time that this intervention was set up, the UK Department of Health announced in a press release plans to set up an expert advisory group to discuss the introduction of routine enquiry for domestic violence in maternity settings to target women at an early stage of the abuse. However, maternity and sexual health services are probably better described as “opportune” points of intervention, as some women using the maternity services revealed well established histories of partner violence. Findings from the interviews suggest that women's usual coping strategies may be compromised during pregnancy, when they are physically more vulnerable to assault, less mobile, more dependent on their partner for practical support, and may be suffering from depression. Factors that prompted pregnant women to disclose abuse included: a partner's threat to remove the baby, escalation in the frequency or severity of violence, desire to protect the unborn child from physical harm, or humiliation by the abuser in front of health workers.

“…the relationship with my husband was deteriorating when I was pregnant, so the first people that I got in contact with were the midwives, really to say that I'm in this situation. ‘Cos I'm carrying the baby and I was worried about that.” (Maternity service user 2, 47 yrs, 8 months post-intervention)

“I had to tell [the doctor]. I had to protect my son just in case he might have turned up at the hospital to try something. Shortly after I had the baby he physically abused me again so I had to make it known to someone.” (Maternity service user 3, 31 yrs, 13 months post-intervention)

“I kept, you know, disassociating myself from domestic violence… But you know after receiving the pamphlets and reading certain things, I was thinking, I've experienced this.” (Maternity service user 4, 33 yrs, 5 months post-intervention)

The inclusion of the sexual health clinic as the second site for the intervention was based on researchCitation16 that women affected by domestic violence are at higher risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and experience difficulties negotiating contraceptive use compared to non-abused women. In addition, abusive partners are more likely to engage in high risk sexual practices, such as unprotected sex with multiple partners, thereby putting the woman at risk for STIs. Women in the sexual health clinic who disclosed partner violence also had STIs, described lack of control over sexual practices, partner risk behaviours (e.g. injecting drug use and multiple partners), and more severe violence, including sexual abuse and rape.

“I was constantly coming to the clinic, which I was feeling ashamed of. It's like people are asking you ‘Well, why don't you use condoms?’ and you're thinking, right, how can you tell someone that you can't use them and you don't even wanna have sex, you're being forced into it.” (Sexual health service user 1, 43 yrs, 14 months post-intervention)

“I was there about the smear test… and when they're trying to put the instrument inside I was having a lot of pain. It was very, very uncomfortable and I said to her I don't know if this is the cause, but I'm having lots of problems in my marriage… She was asking about what sort of problem I'm having and I said, well, I just have a very violent and a very abusive partner and I've actually moved out of the bedroom… Even when you said no and try to fight him off, that's where most of the trouble actually started 'cos he practically attacked me in my bed.” (Sexual health service user 2, 48 yrs, 2 months post-intervention)

• Assumption 4: Women who receive support from a domestic violence advocacy service are able to improve their personal situation.

The interviews with women provided insights into the complex contextual factors that affected the outcome of the intervention. Some reflected on positive outcomes they had achieved whilst still living with the abuser. Some described a process of re-evaluating their strengths and skills, an increased understanding of the dynamics of the abusive relationship and the negative impact that it was having on their family. For women in the early stages of deciding what to do, the support offered often initiated a process of re-assessing their situation, gaining insights about themselves and the relationship, and gaining confidence in their ability to begin and sustain changes. They were able to tentatively explore options such as temporarily leaving the abusive situation, enquiring about welfare benefits for single parents, contacting the police to diffuse a volatile situation, and seeking advice from a solicitor.

“I was scared and I think that was the thing that came out in the initial meeting, was making sure that they wouldn't just run to the police and get him locked up… It scared me that kind of decision would be taken out of my hands… It was non-judgemental, the counselling was kept very balanced in that way, so I was not being led down an avenue.” (Hospital staff member who received advocacy 1, 52 yrs, 8 months post-intervention)

“I think that with [the advocacy project] for instance, the work they do with just supporting women through the process. I think that's very important. And through the process of maturing, you know, the idea of leaving.” (Sexual health service user 3, 33 yrs, 14 months post-intervention)

“…it's really, really hard to be in this country without your status and you are with somebody who is hitting you or doing bad things to you… He's using that as a weapon to hurt you more because he knows that whatever he [does] to you, you [can't] do anything about it.” (Maternity service user 4, 28 yrs, 9 months post-intervention)

“I'd literally sleep with a knife or something next to me because I thought I don't know what's going on. And you know two, three o'clock in the morning my front door would be knocking and it would be him knocking. And because I'm not opening the door, ‘Oh, I know you've got a man in there you bitch, open the door.’ And he's kicking the door down, banging the windows and he's woken up my son and the baby.” (Maternity service user 3, 33 yrs, 5 months post-intervention)

“In here [the refuge] there's no space… and everything gets to me sometimes… I still think about [him] and I'm scared that once I'm re-housed I'll still wanna see him… I think it has to do with loneliness. I feel really lonely.” (Maternity service user 5, 35 yrs, 13 months post-intervention)

• Assumption 5: Routine enquiry about violence and advocacy will not result in harm.

In as sensitive and potentially dangerous an area as domestic violence, the assumption that a programmatic intervention will not result in harm is questionable. We identified several potential sources of harm during the evaluation, including negative labelling and stereotyping of women by health professionals, breaches of confidentiality, failure to act on information, and failure to document adequately or provide copies of documentation in a timely manner for women pursuing civil remedies. A woman who was receiving treatment for depression and domestic violence advocacy support described being discharged with her baby from the post-natal ward to her abusive partner's home, although her case notes clearly stated that she was awaiting emergency accommodation and should not be discharged without her doctor's agreement. Breaches of confidentiality described by interviewees included the abuse being discussed in front of, or conveyed to, other family members by health practitioners.

A discrete coding system was used in patient records to indicate that a health professional had enquired about domestic violence, the patient's response, and whether referral to advocacy was discussed. A Confidential Abuse Documentation Form was provided for detailed documentation of violence. Of the 20 instances of domestic violence recorded in the patient records we examined, however, only one woman had a Confidential Abuse Documentation Form. Health professionals felt documentation was time-consuming, could not remember where to find the form, had documented it elsewhere, or had simply forgotten to do it.

“I actually forgot that there was a domestic violence code, so I personally haven't been as diligent as… I have been for coding for a genitourinary infection.” (Sexual health, Doctor 1)

“…I think people get a disclosure, refer to [the advocacy project] and close the book on it.” (Midwife & domestic violence co-trainer 1)

“There haven't been any problems with filing stuff in the post-natal cabinet because we also use it for, like, child protection issues as well.” (Midwife 4)

“I don't recall anything being documented. I think [the doctor] might have put it in the medical notes at the time… I think in the [hand-held maternity notes] 'cos I was punched in the stomach and I remember him doing a drawing and he also sent me for a scan to make sure that everything was okay.” (Maternity service user 3, 33 yrs, 5 months post-intervention)

“The doctor that I have now, the surgery is very good, but when I needed the notes for the injunction everything was ‘alleged this’ and ‘alleged that’. But I felt having the midwife's report did help actually… I was able to give the judge other instances of things that had happened. He was satisfied at the initial hearing that this event had taken place.” (Maternity service user 6, 40 yrs, <1 month post-intervention)

Discussion

Our findings suggest that both maternity and sexual health services can provide opportune points of intervention for women experiencing domestic violence. Some of the women appeared to have benefited from their referral to the advocacy service, and the majority left their abuser. However, leaving did not necessarily end the abuse for some, suggesting that post-separation interventions are essential to maintaining women and children's safety and well-being. Longitudinal studies are needed to learn more about the factors that accelerate or impede women's routes to safety. During the early stages of an abusive relationship, some women strive to maintain the appearance of having a normal relationship by isolating themselves and managing or coping with the abuse.Citation17 Health professionals may therefore be more successful at detecting severe cases of abuse through routine enquiry.

The training programme results were promising, with demonstrable improvements in health professionals' knowledge and clinical practice, at least in the short term. However, although considerably increasing coverage in the maternity service, the training did not achieve universal enquiry for domestic violence in either setting by the end of the evaluation, a finding that has also been reported in several US studies.Citation18Citation19 Results from the questionnaires and interviews suggest that training methods should encourage experiential learning and skills practice, with feedback sessions. Furthermore, training also needs to be tailored to the particular clinical setting and patient group. Follow-up training, ongoing clinical supervision, partnerships with specialist domestic violence agencies and clear referral processes are necessary to promote sustainable changes in health professionals' practice.

Consistent with other studies, it would appear that this intervention was less successful at improving documentation of domestic violence.Citation18Citation20 Responding to domestic violence requires great sensitivity and skill by health professionals and advocacy workers if they are to intervene in a way that benefits women and their children and does not cause harm. We need more robust data on the benefits and potential harms of such interventions.Citation21 To our knowledge this is the first study to try to identify potential sources of harm in programme implementation in a detailed manner. The incidents were infrequent, but were potentially serious. Poor quality or no documentation means that health professionals are less able to address the patient's needs clinically, assess risk, ascertain the ongoing nature of abuse, refer for appropriate support, or provide evidence for legal and other civil purposes. Programmatic Interventions of this kind are complex, fluid and challenging. There is a need for ongoing review, adaptation and improvement - in this case with regard to improved coverage of routine enquiry, better documentation and respect for confidentiality. If these areas can be tackled successfully, then there is evidence that this model of intervention can detect and support women who are experiencing domestic violence.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Guy's & St. Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust, staff at the MOZAIC Women's Wellbeing Project, the 170 Community Project, and all users of and health professionals at the maternity and sexual health services who participated in the study. The study was fully funded by Guy's & St Thomas' Charity (Grant No.G040204).

References

- EG Krug, LL Dahlberg, JA Mercy. World Report on Violence and Health. 2002; World Health Organisation: GenevaAt: <www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/en/?>. Accessed 3 September 2010

- C Garcia-Moreno, H Jansen, M Ellsberg. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. Lancet. 368: 2006; 1260–1269.

- C Garcia-Moreno. Dilemmas and opportunities for an appropriate health-service response to violence against women. Lancet. 359: 2002; 1509–1514.

- A Taket, CN Wathen, H MacMillan. Should health professionals screen all women for domestic violence?. PLoS Medicine Public Library of Science. 1: 2004; 7–10.

- Ramsay J, Carter YH, Davidson LL, et al. Advocacy interventions to reduce or eliminate violence and promote the physical and psychosocial well-being of women who experience intimate partner abuse. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009; 8 July.

- L Bacchus, G Mezey, S Bewley. Women's perceptions and experiences of routine screening for domestic violence in a maternity service. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 109: 2002; 9–16.

- J Davies, E Lyon, D Monti-Catania. Safety Planning with Battered Women. Complex Lives, Difficult Choices. 1998; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks California.

- JP Connell, AC Kubisch. Applying a theory of change approach to the evaluation of comprehensive community initiatives: progress, prospects and problems. A Fullbright-Anderson, AC Kubisch, JP Connell. New Approaches to Evaluating Community Initiatives. 1998; Aspen Institute: Washington DC.

- HT Chen. Practical Program Evaluation. 2005; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks.

- JD Birkmayer, CH Weiss. Theory-based evaluation in practice. What do we learn?. Evaluation Review. 24: 2000; 407–431.

- L Bacchus, G Aston, C Torres Vitolas. A theory-based evaluation of a multi-agency domestic violence service based in maternity and genitourinary services at Guy's & St. Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust. 2007; Kings College London: LondonAt: <www.kcl.ac.uk/schools/nursing/research/themes/women/projects/maternal/domesticviolence.html>. Accessed 28 June 2010

- BR Dixon, GD Bourma, GBJ Atkinson. A Handbook of Social Science Research. A comprehensive and practical guide for students. 1987; Oxford University Press: Oxford.

- Murray SF, Buller AM, Bewley S, et al. Metrics for monitoring local inequalities in access to maternity care: developing a basket of markers from routinely available data. Quality and Safety in Healthcare. Online. doi:10.1136/qshc.2008.032136.

- C Torres-Vitolas, LJ Bacchus, G Aston. A comparison of the training needs of maternity and sexual health professionals in a London teaching hospital with regards to routine enquiry for domestic abuse. Public Health. 124: 2010; 472–478.

- JL Jasinski. Pregnancy and domestic violence: a review of the literature. Trauma Violence & Abuse. 5: 2004; 47–64.

- GM Wingwood, RJ DiClemente, A Raj. Adverse consequences of intimate partner abuse among women in non-urban domestic violence shelters. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 19: 2000; 270–275.

- K Cavanagh. Understanding women's responses to domestic violence. Qualitative Social Work. 2: 2003; 229–249.

- TS Harwell, RJ Casten, KA Armstrong. Results of a domestic violence training program offered to staff of urban community health centers. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 15: 1998; 235–242.

- RS Thompson, FP Rivara, DC Thompson. Identification and management of domestic violence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 19: 2000; 253–263.

- AM Gadomski, D Wolff, M Tripp. Changes in health care providers' knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and behaviours regarding domestic violence, following a multifaceted intervention. Academic Medicine. 76: 2001; 1045–1052.

- G Feder, J Ramsey, D Dunne. How far does screening women for domestic (partner) violence in different health-care settings meet criteria for a screening programme? Systematic reviews of nine UK National Screening Committee criteria. Health Technology Assessment. 13: 2009; 1–136.