Brazilian women have seen important setbacks in regard to access to abortion in recent years. A clear turning point was September 2005, when a law aimed at reforming existing punitive legislation on abortion – which currently is illegal except in cases of rape or when the mother's life is in danger – was presented to the Congress without the required support of the executive branch. A few months earlier, responding to a resolution to decriminalize abortion passed at the First National Conference on Women's Policies in 2004,Citation1 the government had in fact called for the formation of a tripartite commission to revise the penal code on abortion. But when, in August 2005, the Commission delivered a draft bill to legalize abortion, it got caught up in the complexities of a full-blown corruption crisis linked to the Pope's visit to Brazil.Citation2

The present storm of criticism from many different sectors of society of the III National Program for Human Rights Policies,Citation3 even from members of the president's own cabinet, is therefore just another chapter in this ongoing saga.Footnote* One good thing to come out of it is that the current controversy has allowed for abortion to be discussed widely in Brazil, and, for the first time, as a human rights issue. It is not trivial either that the macro-level political bargains triggered by recent political controversies have situated abortion as the “other” problematic issue to be negotiated among key actors (in addition to the proposed truth commission).

To understand the meaning and complexity of the debate underway, it is worth re-visiting contemporary Brazilian history. As in other countries in Latin America, the progressive Catholic church of the time was a key defender of political and civil rights during dictatorship. The conservative Catholic church that emerged after the election of John Paul II as Pope in 1979, however, systematically contested all advances in the area of sexual and reproductive rights (particularly regarding abortion) that emerged as a result of democratization.

The resistance of the Brazilian military and of some sectors of the political elite to fully reviewing state crimes committed during the military regime is another key feature to be highlighted. In Chile, South Africa, and Peru (after the Fujimori authoritarian period), commissions of truth and reconciliation were established. In Uruguay and Argentina, clear and sharp judicial review and punishment of military dictatorship crimes have also taken place and are still underway. But in Brazil, the 1979 Amnesty Law that “pardoned” those engaged in political and armed action against the regime has also forgiven state actors involved in human rights abuses and is consistently interpreted, by those resisting a full historical review, as a final and definitive closure of the past.

However, in the mid-1990s, a Commission was established at the Ministry of Justice to search for missing persons and unidentified bodies and to compensate people financially who had lost family members, as well as people whose professional careers had been affected by political persecution. No full review of state crimes committed between 1964 and 1984 has been conducted, however. The objective of the truth commission proposed in the III National Program for Human Rights was to complete the difficult work of historical review and closure.

The III National Program for Human Rights by and large maintains and expands proposals contained in a previous programme, which was adopted in 2002 (at the end of the Cardoso administration). But it also incorporates language coming from a variety of sources: existing legislation on human rights of specific groups (such as children and indigenous people); recommendations from the periodic National Conferences on Human Rights and other conferences that directly address human rights issues (such as the National Conferences on Health, on Women's Public Policies, on Public Policies for the LGBT population and so forth); recommendations from international conventions; and other relevant international documents.

The III National Program for Human Rights recognizes that human rights are indivisible in that they encompass civil, political, economic, and social rights. The document covers a wide range of subjects such as: food security; the right to health and within it, further regulation of private health insurance; prison conditions and rights of incarcerated persons; judicial procedures regarding rural property occupation by landless peasants; genetically modified seeds; social accountability of media outlets; same-sex civil unions; and the display of religious symbols in public buildings.

In relation to abortion specifically, a proposal to revise existing laws punishing abortion – derived from the Beijing Platform – was already included in the 2002 programme. The language adopted in the III National Program for Human Rights is based on the First National Plan for Women's Policy (2004) and calls for the decriminalization of abortion to guarantee women's autonomy over their bodies.

The document, although prepared by the National Special Secretary for Human Rights, was revised by all concerned ministries and signed by their respective ministers. However, when, in January, 2010, its contents became public, and were absorbed by key political actors, harsh controversies erupted within government itself regarding various parts of the document. Two ministers openly expressed their disagreement with the text. The Minister of Agriculture complained about the plan's call to ban genetically modified seeds. Most critically, the Minister of Defence, who is a civilian, publicly declared that the military did not accept the language adopted in relation to the commission of truth, as it exclusively referred to crimes committed by state actors, without recognizing the human rights abuses committed by political dissidents.

Concurrently, other actors raised their voices against other critical areas. Representatives of rural landowners complained about the judicial rules concerning land occupation. Private health insurance companies argued against proposals regarding ceilings in premium costs for ageing people. The media contested the call for greater social accountability. Most importantly, the Catholic church immediately expressed its full opposition to the proposals on the legalization of both abortion and same-sex marriage, as well as the proposal about the display of religious symbols in public edifices. The main complaint of Catholic bishops was that the Program went against “defence of the right to life”. While a large number of content areas of the third programme were contested and discussed, it is significant that the debate very quickly crystallized predominantly around the truth commission and abortion.

In response to the reaction of the minister of defense, speaking on behalf of conservative voices within the military, the National Secretary for Human Rights threatened to resign, and President Lula very quickly called a closed meeting between the two ministers to find a solution to the crisis. After the meeting, a new presidential decree was immediately published. It changed the language originally adopted by the Program, eliminating the term “political repression” in order to dilute the exclusive focus on state violations. This quick move has muted, at least for the time being, the conservative military reaction. The public debate on the matter, however, has made it clear that the truth commission has wide public support. However, it is too soon to claim that the controversy is fully resolved, as it may re-emerge when the subject is debated in Congress.

The dynamics of the political bargaining that took place were, however, completely different in the case of the abortion debate. While the “truth commission problem” was being processed, the Secretary for Human Rights declared that the text on abortion should be changed because, he said, the justification used for legalizing abortion – to “guarantee women's autonomy” – was a feminist argument and did not reflect the government's position on the subject. Although he did not explicitly state what the official position was, previous episodes concerning abortion suggest that it would involve framing abortion as a major public health problem (and eventually maintaining the law as it stands today).Footnote*

Immediately after this declaration, the Secretary for Human Rights met with the representative of the National Conference to discuss the matter. Almost a month elapsed before he met with the feminist organizations representing the voices of those who support abortion law reform. Right after that meeting, he stated that the government would seek support for the Program from the international human rights system. In fact, the UN High Commissioner Navi Pillai, who in May 2010, visited Brazil, had already published an article in the Brazilian newspaper Folha de São Paulo openly supporting the creation of the truth commission. But the next governmental step would be to ask UNESCO to consider the dictatorship archives and a patrimony of humanity and to have the Office of the High Commissioner assess the consistency of the III Program with existing international human rights law. Resorting to international human rights instruments to defend the III Program was certainly a quite remarkable step. However, it should also be noted that while existing international instruments provide strong supporting arguments for the topics relating to political persecution and measures for truth investigation, the identification of international human rights language on sexuality and abortion is more complex. It will require the content of international conference documents and of recommendations issued by human rights surveillance organizations to be made visible and valued.

During the first two months of 2010, feminists and other sectors have mobilized countrywide to support the Program, particularly around 8 March, International Women's Day. But on March 16th, the press announced that the National Secretary for Human Rights had declared that three items included on the plan would be eliminated or modified: the recommendation on religious symbols in public buildings, the rules concerning land occupation, and, evidently, the language on legalization of abortion. Not surprisingly, the next day, the police closed an abortion clinic located in a poor area of downtown Rio de Janeiro and health professionals and patients (some of them bleeding) were criminally indicted.

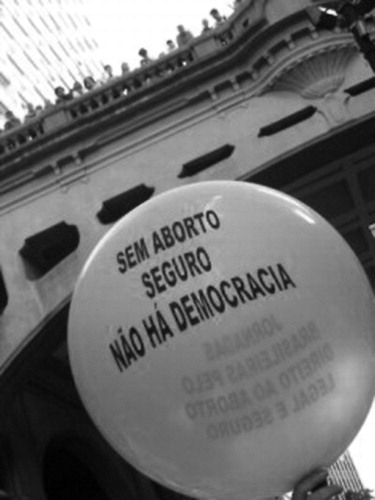

Petitions and protests against the decision announced by the Minister quickly circulated. Feminist organizations gathered around the Brazilian Initiative for the Right to Legal and Safe Abortion (Jornadas por um Aborto Legal e Seguro)Citation4 and signed a public letter making it clear that they would not accept any change in the language adopted by the III Program. On 19 March, in a public event organized by the Public Defenders' Office in Rio de Janeiro to discuss the III Program, the Secretary said that, in relation to the abortion debate, he had consulted not only the bishops but also Catholics for Choice. Most importantly, he informed the audience that the call for decriminalizing abortion would not be eliminated but that language would be modified to be consistent with what is written in the 1995 Fourth World Conference on Women (Beijing) Platform of Action (Paragraph 106k, which combines Paragraph 8.25 of ICPD with the recommendation that countries must revise punitive legislation). But this was not to be the end of the debate.

On 27 April, 2010, the National Secretary for Human Rights declared again that the language on abortion would be amended so as to address it as a major public health problem and to recommend decriminalization along the lines of Beijing Paragraph 106k. Then on the 29th, the Supreme Court finally ruled in the case presented by the National Bar Association (OAB Brasil) that torture and killing, being crimes against humanity, should be excluded from the general pardon contained in the 1979 Amnesty Law. Seven judges voted against, preserving the “closure” of the 1979 Amnesty Law.

The entire episode is revealing of the complex contradictions of the Lula administration, which are not always easily understood by those who do not experience the daily dynamics of domestic politics. These contradictions involve both internal, high level tensions and big gaps between the positions expressed by civil society voices in participatory policy mechanisms – such as international conferences – and official positions that are usually framed in terms of economic interests and electoral bargains. Trends and skirmishes observed between January and April 2010 revealed, once again, how legalization of abortion was deeply caught within the complex webs of a major political trade-off in which the real prize at stake was the truth commission. It is not trivial either that the Catholic Church, which was a major advocate for political rights during dictatorship, is once again fully opposing abortion, same-sex marriage and secular rules about the display of religious symbols. And most principally the Supreme Court decision is not a good sign in terms of the future of Brazilian democracy in its broader sense.

In fact, despite the positive signs seen in late April, further regression in relation to abortion was yet to come. On May 13th, President Lula finally signed a new decree altering the text of III National Program for Human Rights in relation to decriminalization of abortion, the prohibition of religious symbols displayed in public buildings, social accountability of the media, and procedures regarding the mediation of agrarian conflicts. Particularly in respect to abortion the new text simply stated:

“Abortion is considered to be a public health problem in relation to which access to health services is to be ensured.”

The approval of the bill in the commitee follows a well-known pattern that began in 2005: whenever the executive branch backpedals, anti-abortion forces make a jump forward. Despite the last minute manoeuvre to preserve Article 128, the preliminary provision also makes clear that the main goal of anti-choice forces is to further restrict the law. This is not a surprise either. In 2007 when the Pope visited Brazil, a Brazilian priest who is a member of Human Rights International announced publicly that their goal was to make Brazil “a big Nicaragua”.

Parts of the bill are impossible to fathom, e.g: “It is forbidden for the State and private individuals to cause any injury to the unborn by reason of acts performed by any of the parents.” One article establishes publicly-funded “incentives” for women who become pregnant as a result of rape not to terminate the pregnancy. The incentives include antenatal assistance, psychological support, state support for the child to be placed for adoption if the woman agrees, and provisions to compel the “father” to pay “alimony” and in case he is not identified, “alimony” will be provided by the state.

Feminists have reacted strongly to these proposals, because if adopted, they will mean state legitimization of sexual violence, complicity with the crime of rape and total disregard for the physical and psychological effects of rape. Some voices have also argued that offering women inducements to take to term an unwanted pregnancy resulting from rape can be interpreted as forced pregnancy and equated with torture.

The Finances and Tax Commission must now analyze the budgetary and financial implications of the bill. Subsequently, the Committee on Constitution, Justice and Citizenship will assess its constitutionality and make revisions before sending it to the House for a vote.

Stop press

Since June 2010, the debate on abortion has continued to be interwoven with the complex political dynamics of the national election period in Brazil. Even before the campaign was in full-fledged mode, after August, abortion had already become one of the main issues. Firstly because, quite early on, the press called upon the candidates to manifest their views on the subject, which made it clear that none of the main candidates were in favour of legal abortion and in most cases their positions had shifted, sometimes dramatically. Marina Silva from the Green Party, who belongs to the Assembly of God, had quite early on declared herself to be against abortion for religious reasons, and although she has been pressured by her supporters, who are in favour of abortion, has maintained the position that the question should be resolved in a referendum.

Dilma Roussef, from Lula's Workers Party, who led the pool until the first round of the presidential run-off on 3 October 2010, had previously declared in Marie Claire magazine in early 2009 that abortion was always a difficult decision, but that it should be considered a major public health problem and therefore legalized. By May 2010, she had moved towards a much more careful position to say, in consonance with the III National Plan for Human Rights, that “abortion is a matter of public health services”. However, this “strategic” retreat has not spared her from pressure and attacks by dogmatic religious leaders, including Catholic bishops, which led her to have a closed conversation with the President of the National Bishops Conference, in August, 2010.

Since then, Dilma's previous open support for legal abortion has been extensively used by the third candidate, José Serra, from the PSDB (the social democratic party) and others to attack her. Serra himself, who as the then Minister of Health in 1998 signed the Ministry of Health protocol that ensured access to abortion under the current law, has totally regressed to an openly anti-abortion position hidden behind a discourse of supporting of “maternal health”. In July he declared that if abortion was legalized a “carnage would occur”. As if this was not enough, his wife made a public declaration saying that Dilma was not trustworthy because she supported legal abortion and would “kill small children” (a popular saying used to describe evil people).

In the last week of the first round of the campaign, the scenario was such that only two presidential candidates from minority left-wing parties openly support legal abortion. But where it really counts – among the candidates most likely to win – abortion had become, as never before, a major, divisive electoral issue. Polls showed that in a short space of time, Dilma lost her considerable advantage over the other candidates for many reasons, not least a corruption scandal that erupted in early September 2010. But various analysts discussing the electoral scenario today included “the abortion issue” as one of the factors behind her losing ground. Two days before the elections, she sat with representatives of the National Pastors Conference and Catholic church representatives to discuss rumours about her position on abortion and gay marriage. She then declared herself personally against abortion, but defended public health care for women who have undergone abortion. Marina Silva declared that Dilma Roussef had changed her position for “electoral convenience”, at which point the issue exploded in the major media. In addition, large paid advertisements for “pro-life” candidates were posted, in colour, in the main pages of some of the major newspapers, and read: VOTE AGAINST ABORTION, in just those words.

The “abortion issue”, surprisingly enough, has also affected Marina, who was the main beneficiary of the votes Dilma lost, particularly in Rio de Janeiro, Brasilia and Belo Horizonte. However, in the last week of campaign one of the better known evangelical pastors in Rio publicly declared that he was not supporting her anymore because she was “lying about her views on abortion”. He claimed that her proposal of a referendum was a mere smokescreen to hide her intention to legalize the procedure. And he shifted his vote to Serra.

The results of the election on 3 October were Dilma 46%, Serra 33%, and Marina 19%, making a second round necessary, and campaigning started off with abortion as the key issue. Between 4 October and 13 October, practically no other issue has been systematically debated in the press, neither economic nor social policies, let alone environmental challenges. Dilma and Serra spent the first week accusing each other of being the one who was more in favour of abortion. High level people in the PT, Dilma's party, suggested that legalization of abortion should be eliminated from the party's programme. All the major weekly magazines had abortion and the election as their cover stories.

On 11 October, Datafolha, one of the major national institutes of public opinion, released the results of a poll carried out after the first round election results were in, which indicated that abortion was not the major reason why votes had been shifting away from Dilma to other candidates, particularly to Marina. Instead, the poll suggested that corruption issues had been more important as negative factors against the two main contenders, but affecting Dilma's support most.

Even so, the main actors involved, particularly the dogmatic religious forces, have not let the issue go away. On 15 October, Dilma, President Lula and the coordinators of her campaign had a closed meeting with the Evangelic leadership in Congress, after which the press announced that she would soon be making a public announcement that she would not support legal abortion or same-sex marriage or the pending provision on criminalisation of homophobia. The religious leaders at the meeting also asked for measures against prostitution and drug use.

Subsequently, in a turbulent TV interview, Dilma said the commitment being discussed was not to send any law provision for abortion legal reform. She also clarified that in her view civil union is different from “marriage”, which is a religious matter, and explained that the law criminalizing homophobia must be changed because the text as it is now infringes upon freedom of religious expression. Next day, some press vehicles informed that she was reluctant to sign the commitment in relation to abortion, while others announced that Serra had made explicit his support for same-sex civil union. Finally on October 15th late afternoon Dilma made public a letter that makes clear that: 1) she is against abortion and will not take any initiative to change existing laws in this domain, 2) her government will emphasize policies and programmes to protect the family.5

But a few glimmers of light can be found in this dark scenario. Back in July 2010, during the 11th Latin American and Caribbean Regional Conference on Women, sponsored by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), the Brazilian delegation pushed for a declaration from the meeting re-affirming Cairo and Beijing language on abortion.Footnote*

In addition, on 28 September this year, the day marking the Campaign for the Decriminalization of Abortion, there were a wide range of events in Brazil, and a number of forward-looking documents were launched, including a new model bill aimed at legalizing abortion. This bill, initiated by CLADEM, the Feminist Network on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights and the Commission on Citizenship and Reproduction, is also supported by a number of other organizations and has been presented to society as a basis for discussion that may lead to a legal reform bill in the legislature in 2011. More importantly, the electoral climate, though extremely worrying and virulent, has also opened a window of opportunity for those in favour of legal abortion and concerned with the preservation of the principles and practice of secularism to express their views strongly.

On October 13th a group of activists and researchers launched a public petition calling for a sane and reasonable debate on abortion. The petition was signed by more than 3.000 people in less than 48 hours and is now circulating internationally. On October 15th a few hours before Dilmas’s letter was made public, the Brazilian Association for LGBT rights also delivered an open letter to presidential candidates calling for full respect for secular values and a commitment to the human rights of those whose sexuality does not conform with dominant heterosexual norms.

As worrying as the climate may be, this is clearly just another chapter in the long, winding and difficult road of making abortion legal and safe in Brazil. While it is certainly premature to predict that Brazil will or will not become another Nicaragua, it is quite clear that Brazilian electoral politics are becoming similar to what has been witnessed in the United States over the last two decades.

Stop stop press

On 31 October 2010, Dilma Rousseff won a resounding victory with 56% of the vote to become Brazil’s first female president.

Acknowledgements

This paper was originally published in the Sexuality Policy Watch Newsletter No.8, 2010, and reprinted online on RH Reality Check, 15 June 2010, at: <www.rhrealitycheck.org/blog/2010/06/13/abortion-human-rights-current-controversy-brazil>. The Stop press was updated from the Sexuality Policy Watch Newsletter No.9, October 2010.

Notes

* The III Program calls for reform of amnesty law, abortion, same-sex civil union, media regulation and land reform, in addition to a truth commission to investigate torture, killings and disappearances during military rule (1964 to 1985), similar to that of Argentina and Chile.

* Unsafe abortion is indeed a major public health problem in Brazil: roughly one in five Brazilian women have an abortion in their lifetime, and many end up in hospital with complications that need never have occurred if abortion had been legal.

* Ironically, the US delegation did not join the consensus, for reasons that are not yet clear.

References

- M Osava. Turning women's rights into reality. 16 August 2007. At: <http://ipsnews.net/news.asp?idnews=38922>

- Castilhos W. The Pope's visit to Brazil: context and effects. Sexuality Policy Watch Working Papers No.5. July 2008.

- R Tsavkko García. Brazil – the National Program for Human Rights Part I. At: <http://globalvoicesonline.org/2010/01/27/brazil-the-national-program-for-human-rights-part-1/>

- To read more about the initiative, its origins and achievements see Sardenberg C. The right to abortion: briefing from Brazil. 50.50 Inclusive Democracy. At: <www.opendemocracy.net/article/5050/how_feminists_make_progress>. 26 October 2007.