Abstract

Abstract

Female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C), officially referred to as female circumcision and at community level as tahara (cleanliness), is still prevalent in Egypt. This study was designed to examine the role of female sexuality in women's and men's continued support for FGM/C, and their perceptions of its sexual consequences. The study was conducted in 2008–09 in two rural communities in Upper Egypt and a large slum area in Cairo. Qualitative data were collected from 102 women and 99 men through focus group discussions and interviews. The clitoris was perceived to be important to, and a source of, sexual desire rather than sexual pleasure. FGM/C was intended to reduce women's sexual appetite and increase women's chastity, but was generally not believed to reduce women's sexual pleasure. Men and women framed sexual pleasure differently, however. While men, especially younger men, considered sexual satisfaction as a cornerstone of marital happiness, women considered themselves sexually satisfied if there was marital harmony and their socio-economic situation was satisfactory. However, sexual problems, including lack of pleasure in sex and sexual dissatisfaction, for whatever reasons, were widespread. We conclude that political commitment is necessary to combat FGM/C and that legal measures must be combined with comprehensive sexuality education, including on misconceptions about FGM/C.

Résumé

La mutilation sexuelle féminine/excision (MSF), appelée aussi circoncision féminine et tahara (purification) au niveau communautaire, est encore très répandue en Égypte. Cette étude avait pour but d'examiner le rôle de la sexualité féminine dans le soutien qu'hommes et femmes continuent d'apporter à cette pratique, et leurs perceptions de ses conséquences sexuelles. L'étude a été réalisée en 2008–09 dans deux communautés rurales de Haute-Égypte et un vaste bidonville du Caire. Des données qualitatives ont été recueillies auprès de 102 femmes et 99 hommes par des entretiens et des discussions en groupes d'intérêt. Le clitoris était jugé important et source de désir sexuel plutôt que de plaisir sexuel. La MSF servait à réduire l'appétit sexuel des femmes et favoriser leur chasteté, mais en général, on ne pensait pas qu'elle réduisait le plaisir sexuel féminin. Néanmoins, les hommes et les femmes concevaient différemment le plaisir sexuel. Alors que les hommes, en particulier les plus jeunes, considéraient la satisfaction sexuelle comme la clé de voûte du bonheur conjugal, les femmes s'estimaient sexuellement satisfaites si l'harmonie régnait dans leur ménage et si leur situation socio-économique était bonne. Les problèmes sexuels, notamment le manque de plaisir pendant les rapports et l'insatisfaction sexuelle, toutes raisons confondues, étaient cependant fréquents. Nous en concluons qu'un engagement politique est nécessaire pour lutter contre la MSF et qu'il faut associer des mesures juridiques à une éducation sexuelle complète, y compris sur les idées fausses relatives à la MSF.

Resumen

La ablación o mutilación genital femenina (MGF), oficialmente conocida como circuncisión femenina y a nivel comunitario como tahara (aseo), aún es frecuente en Egipto. Este estudio fue diseñado para examinar el papel de la sexualidad femenina en el continuo apoyo de la MGF por hombres y mujeres, y sus percepciones de sus consecuencias sexuales. El estudio fue realizado en 2008–09 en dos comunidades rurales en Alto Egipto y en una amplia zona de barrios bajos del Cairo. Se recolectaron datos cualitativos de 102 mujeres y 99 hombres, por medio de discusiones en grupos focales y entrevistas. El clítoris era percibido como algo importante para el deseo sexual y como una fuente de deseo sexual en vez de placer sexual. La MGF tenía como objetivo reducir el apetito sexual de las mujeres y aumentar su castidad, pero generalmente no se consideraba como algo para disminuir el placer sexual de las mujeres. No obstante, la definición de placer sexual ofrecida por los hombres era distinta a la de las mujeres. Mientras que los hombres, especialmente los más jóvenes, consideraban la satisfacción sexual como algo fundamental para la felicidad matrimonial, las mujeres se consideraban sexualmente satisfechas si había armonía conyugal y su situación socioeconómica era satisfactoria. Sin embargo, los problemas sexuales como la falta de placer sexual y la insatisfacción sexual, por las razones que fueran, eran extendidos. Concluimos que el compromiso político es necesario para combatir la MGF y que las medidas jurídicas se deben combinar con una educación sexual integral, que aborde las ideas erróneas respecto a la MGF.

The 2008 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) in Egypt found that 91% of women of reproductive age have undergone female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C),Citation1 down from 97% in 2000.Citation2 Recent studies suggest that the prevalence is falling even more among the younger generation,Citation3Citation4 which is believed to be a result of many years of broad work against the practice.

Girls in Egypt usually undergo the procedure prior to or around puberty. The most common forms fit into two of the four types classified by the World Health Organization (WHO): Type I (removal of part or all of the clitoris) and Type II (removal of the labia minora and part or all of the clitoris).Citation5 In 1996, Type I and Type II accounted for 84% of all cases examined in a large study, with Type III, the most severe, accounting for 9%, while 7% had not undergone the procedure.Citation6

In 1999, a study among 500 doctors working in the Ministry of Health and teaching hospitals showed that just over half of them were in favour of FGM/C for at least some, if not all, women.Citation7 Medicalization of the practice poses serious ethical questions and concerns, with arguments that the procedure violates the basic principles of medical ethics.Citation8Citation9 However, according to the 2008 DHS, doctors in Egypt carry out a large majority (72%) of circumcisions in girls under 17 years of age, and dayas (traditional birth attendants) 21%, as reported by girls' mothers.Citation1

The main motivation reported in 2003 for the practice in Egypt is to maintain the tradition and adhere to what people think is a religious requirement, as well as husband's preference for circumcised wives, and to prevent illicit sexual behaviour in women, particularly premarital and extra-marital sex.Citation10

Prominent Muslim religious leaders including the late Grand Sheikh of Al-Azhar, have spoken out strongly against FGM/C on several occasions, defining it as a socio-cultural belief rather than a religious requirement.Citation11–13 The Egyptian Orthodox church has also spoken against the practice.

Efforts to combat the practice in Egypt date back to the 1920s, beginning mostly with individual initiatives. The first conference to publicly address the issue was held in 1979 by the Cairo Family Planning Association, a leading non-governmental organization (NGO). Since then, more NGOs have added the issue to their agendas, and community efforts have expanded to combat it. The National Task Force against FGM/C, consisting mainly of NGOs, was established immediately after the International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo in 1994. The Task Force succeeded in placing FGM/C on Egypt's agenda and created a dialogue between the different stakeholders.Citation14 In 1989 the National Council for Childhood and Motherhood was established and is currently administered under the Ministry of Family and Population, established in 2009. The Council played a leading role in the fight against FGM/C and had pioneered a nationwide project entitled “Female Genital Mutilation Free Village Model” in 2003. The project is currently present in 120 villages in different Egyptian governorates.Citation14 This project succeeded in engaging all stakeholders and has mobilized public declarations against the practice.

In 2007, the news of two girls who died as a result of circumcision was widely publicized. After the death of a 13-year-old girl, Bedour, following a circumcision performed by a medical doctor, the Ministry of Health issued a decree banning doctors and nurses from performing FGM/C.Citation15 The doctor responsible was sentenced to one year's imprisonment and fined LE 1000 (around US$200). In 2008, with the help of the National Council for Childhood and Motherhood, a law was passed in Parliament, criminalizing FGM/C and imposing harsh penalties on practitioners.Citation16 As of this writing, there had been only one documented case of a daya and a mother being fined and imprisoned for FGM/C. However, several other cases have been reported and are currently being investigated by district attorneys in several governorates (Fouad, National Council for Childhood and Motherhood, Personal communication, 2010).

Relationship between female genital mutilation/cutting and sexuality

Controlling the sexuality of women is often stated as a key motivation in the literature on FGM/C. In Egypt, concerns over the consequences of the practice for women's sexuality have been mentioned in articles and books by Egyptian feminists, such as Nawal El-Sadawi.Citation17 However, none of this literature has attempted to explore what is meant by the consequences for sexuality in the country. We set out to do so.

Our study aimed to investigate a deconstructed conception of sexuality in relationship to FGM/C, including the many issues assumed to shape women's perception of sexuality, such as marriageability, gender roles, and views on masculinity and manhood. We have followed the path of many anthropologists, in that context is considered the main parameter for the construction of sexuality.Citation18–20

The existing literature on FGM/C and sexuality, published from 1965 until today, mostly since the early 1990s,Citation21–38 is conflicting regarding the effects of FGM/C on sexual feelings. Several socio-anthropological studies over the past 20 years have challenged what they call the “western assumption”Footnote* that the clitoris is key to female sexual response, and that FGM/C has a negative effect on sexual feelings.Citation21–28 An extensive literature review, conducted by Obermeyer et al on FGM/C and sexuality, published in 1999, concluded:

“The existing evidence challenges the assumption that the capacity for sexual enjoyment is dependent on an intact clitoris, and that orgasm is the only measure of ‘healthy’ sexuality.” Citation29

A study in Egypt published in 1996, which included 41 women with FGM/C, found that the majority of women reported no negative impact on their sexual relations with their husbands.Citation31 Studies in 1965Citation32 and 1998,Citation33 on the other hand, suggested that circumcised Egyptian women were more likely than others to experience loss of sexual desire. A larger study, published in 2001, which examined 250 women attending family planning centres in Egypt, found that 80% of the circumcised women were more likely to report psychosexual difficulties than the uncircumcised women, including reduced frequency of intercourse, fewer orgasms and less enjoyment of sex.Citation34

A more elaborate hospital-based study in Egypt, published in 2003, found that women with Type I FGM/C experienced no reduction in sexual desire, while those who had undergone Type II or III experienced several sorts of sexual problems.Citation35 These findings are in line with a review in the same year that found that dyspareunia (painful intercourse) was experienced by 16–46% of the women with FGM/C compared to 14–32% of the women without it.Citation36

In 2007, a survey of 1,000 married women in Egypt, of whom more than 90% were circumcised, found that almost 70% of circumcised women experienced some sort of sexual dysfunction. However, most of them did not associate circumcision with what they were experiencing. Marital disharmony and socio-economic pressures were blamed instead.Citation37

Most recently, a systematic review (published on the web in 2010) concluded that the low quality of the body of evidence on the psychological, social and sexual consequences of FGM/C:

“… precludes us from drawing conclusions regarding causality, and the evidence base is insufficient to draw solid conclusions about the psychological and social consequences of FGM/C. However, our results substantiate the proposition that a woman whose genital tissues have been partly removed is more likely to experience increased pain and reduction in sexual satisfaction and desire.” Citation38

Methods and participants

Our first task was to translate the term “sexuality” into colloquial Arabic. Although Arab feminists use the term genisawaya to refer to sexuality, this usage does not exist beyond academia and intellectual circles. Instead, we found that people used phrases like genss (sex), neek (sexual intercourse), motta'a (pleasure), shahwa (desire), and motta'a gensiya (sexual pleasure).

Data were mainly collected through focus groups and in-depth interviews. To enrich the data set, a total of six case studies, and four inter-generational life histories were conducted; in these interviews we pursued the deeper and personal meaning and experiences of the issues. The findings of the case studies and life histories will be presented elsewhere.

A total of 25 focus group discussions were conducted in the three sites, 13 with women and 12 with men, with 94 women and 93 men. The groups were divided by age in order to see whether a difference in thinking had developed over time. Six groups were with women over 35 years of age, seven with women under 35, six with men over 35 and six with men under 35. Each group included educated and non-educated participants, and mixed Moslems and Christians. The vast majority of the women participating were circumcised. In addition, 31 in-depth interviews were conducted in the three sites: eight with women, six with men, four with community leaders, six with religious leaders, and seven with circumcisers and health providers.

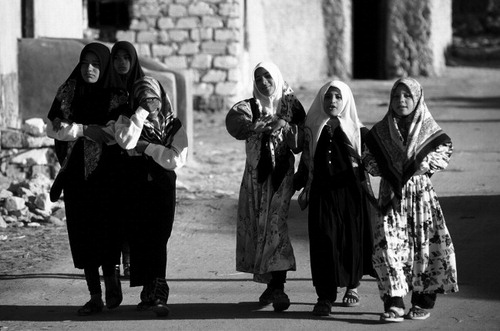

The study was conducted in three sites: one slum area in Cairo, and two villages in Al Minya Governorate around 250 km south of Cairo. The three sites have a mix of Muslim and Christian population and none of the three sites was part of the “Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting Free Village Model” project of the National Council for Childhood and Motherhood. The study locations were selected in consultation with local NGOs. The research team selected three NGOs to assist in the process of site selection and recruitment of the study participants. The NGOs were selected based on their previous and current reputation, diversity of programmes in different communities, relationship with local authorities, and willingness to cooperate with the research team.

The recruited participants were selected from the selected communities by the respective NGOs, based on pre-set criteria such as age, marital status and willingness to participate in the research. Participants in the case studies and inter-generational life histories were random members of the communities who fulfilled the research criteria.

The majority of women participating in the study were either not literate, just able to read and write, or had primary education. The male participants generally had a slightly higher level of education. All the women involved in the study were or had been married at some point, while men were married or non married, it is socially unacceptable to ask women who have never married about their sexual experiences.

All the participants were informed of the objectives of the research, as well as the time that they would be expected to spend with the research team. Verbal consent was obtained prior to all in-depth interviews, focus group discussions, case studies, and intergenerational histories. Tapes and notes were locked in a special compartment with access only for the research team. Because of the sensitivity of the research topics, interviews with women were conducted by a female member of the research team while interviews with men were conducted by a man.

The research team had two doctors who offered to help with any medical problems, questions or concerns the participants might have during the course of the study. Furthermore, those with gynaecological problems were referred for free examination and treatment as required. The study received ethical approval from the World Health Organization and an internal ethical committee of the Cairo Family Planning and Development Association. All data were collected in January and February 2008; the analysis was completed in the first half of 2009.

Findings

FGM/C, sexual desire and sexual drive

FGM/C was still widely practised among the study participants and was deeply rooted in people's minds in all the study sites. The main reason given for supporting the practice was to reduce and regulate girls' and women's sexual desires and sexual drive. In general, among both women and men over age 35, it was believed that uncircumcised women would be “like a restless bull and demand a man” or would “reach orgasm while walking or even if someone holds their hand”.

The clitoris was seen as the site of such strong sexual urges that its presence would make it difficult for women to resist sexual overtures from men. The belief that the clitoris is the seat of sexual desire was the basis of the belief that an intact clitoris created the risk of women losing their virginity before marriage, which is immensely important in Egypt at both a religious and social level.

The focus group discussions also revealed a widespread fear among men that if their wives had not undergone circumcision, the strength of their sexual desire within marriage could also be a risk, that women's sexual demands would be beyond their capacity, with the associated risk that wives might feel the need to engage in extra-marital relations, e.g. if their husbands travel abroad. Exposure to foreign pornographic films, particularly popular among the young men, in which the women in the films were taken to represent western women generally, further strengthened the belief that lack of FGM/C would lead women to be promiscuous due to excessive sexuality.

However, the majority of men and women interviewed said they did not consider the clitoris important for achieving women's sexual satisfaction.

Marriageability

The issue of marriageability has often been cited as the strongest motivation for FGM/C.Citation39 The expectation is that if a woman is not circumcised in a community where this is the norm, her chances of getting married will be severely reduced, and hence her social status and livelihood endangered. In this study, however, neither men nor women described circumcision as a prerequisite for marriage, nor linked the two directly. However, the importance of premarital virginity and marital faithfulness, and the belief that female genital mutilation/cutting helps to accomplish these, may be understood as indirect support for the assumption in these communities that men prefer to marry women with “good behaviour”, and thus women who have been circumcised.

We also found that the circumcision status of the woman appears rarely to be discussed during marriage negotiations, but given the high prevalence of FGM/C it would commonly be assumed that the bride has already undergone the procedure.

Right to sexual pleasure and happiness within marriage

Taking the initiative to have sex is often used as an expression of the extent of women's sexual desire. Hence, measurement of this is believed to say something about women desire for and pleasure in sex.Citation27,35,40 However studies have also shown that women's motives for engaging in and initiating sex go far beyond sexual desire, and include both emotional and practical aspects as well, including duty, desire for children, and the hope that sexual favours may result in material benefits from the husband.Citation41 Our study also found that local sociocultural gender norms also had a strong influence on whether women could initiate sex, and the ways in which they could do so. It was generally considered unacceptable for women to make direct overtures, instead the man was expected to do this, and even to beg for it. It became clear in these conversations that while men are encouraged to express and celebrate their sexual pleasure through physical parameters, women are not.

However, it was considered acceptable, and even desirable, for women to express their availability or interest in sex in a subtle manner, thereby encouraging their husbands to initiate sex. Men and women mentioned various ways in which a woman could entice her husband or show her availability. Activities such as having a shower, preparing a good meal, dressing in special clothes, or walking in a special way were all understood as means women could use.

At the same time, it was not considered appropriate for a woman to refuse sex when their husbands requested it. Both men and women in general considered complying with men's desire for sex as a woman's duty, and in line with Islamic teaching. Some focus groups of men aged over 35 noted that women refusing to have sex without physical reason is not accepted and a woman could be beaten for it.

In contrast, neither women nor most men expected FGM/C to have a negative effect on their sexual pleasure. In response to our questions on sexual pleasure, men, especially younger men, directly connected sexual pleasure to the sexual act itself (intercourse) and saw sexual pleasure as a cornerstone of their marital happiness. For the men, an important reason for marrying was for sex, and being sexually happy meant they were happy in marriage.

Some of the men expressed ambivalence about female genital mutilation/cutting. While they wanted their wives to have undergone the procedure for its perceived beneficial effects on women's sexual morality, they perceived and lamented a negative effect on sexual pleasure. For, in contrast to the women, some of the men, particularly the younger ones, did believe this occurred.

However, those men, mostly young, who did express worries about negative sexual consequences of FGM/C focused in the discussions on how it would affect them. The concern was that it might reduce wives' sexual desire and ability to be sexually engaged, i.e. respond to the husband's overtures and take an active role sexually, which could then have a negative effect on the husband's pleasure.

In contrast to the men, the women generally defined sexual pleasure, satisfaction and happiness within a broader social context such as having a caring and kind husband, happy children and economic needs fulfilled, and in close relation to men's sexual satisfaction. Though the women frequently mentioned that they “felt cold during sexual relations”, “had no satisfaction out of sex” or “had pain during sex” both in the interviews and focus groups, they did not indicate that this distressed them. Rather, they said they bore with this as a marital duty and fulfilment of religious obligations. Some also said their husbands had said they might take another wife if they did not have sex with them.

Views of religious leaders

In fact, almost all the men in the focus group discussions and the religious leaders stated that women have as much right to enjoy sex as men, when the issue is placed in a religious framework

“The holy book gives the right to enjoy sex to both the man and the woman. And the book says do not steal each other's right. A woman has the right to desire her husband.” (Priest, interview)

“Circumcision is not the main factor in sexual desire. A woman could be circumcised but have a very strong sexual desire; or, she could be uncircumcised and have no desire. This needs a medical study.” (Sheikh, interview)

“There is a Prophet's saying that says that a man should not end the act until his wife reaches the peak.” (Sheikh, interview)

“Family problems exist a lot in our area, the woman does not respond to her man. When she has the desire, she does not get satisfied. In these cases, I talk to the man and ask him to cope with the situation and advise him that circumcision is wrong and he has to accept his wife as she is.” (Priest, interview)

Views of health care providers

All the formally trained health care providers had experience of couples coming to see them with sexual problems which, in some instances, they considered to be related to female genital mutilation/cutting:

“A woman came to me a month after marriage with depression saying they had circumcised her six or seven months before; she felt insulted (her pride was insulted by cutting a piece of her flesh). Another comes complaining that her sexual life with her husband is cold, she is afraid he might take another wife. Another asks me for medicines to increase her sexual feeling. This causes problems between the couple.” (Physician, interview)

“There is a general thought that circumcision is important for marriage, men think so, and yet they come afterwards complaining.” (Physician, interview)

“There should be a special place affiliated to the Ministry of Health where female circumcision could be safely done when needed instead of going to a nurse or a daya.” (Doctor, interview)

The new regulations against FGM/C and women' status

There was widespread resistance expressed to official “interference in family affairs”, which was how the decree was seen, and they doubted its efficacy in stopping the practice. Some younger men said they would still “have it done at home”. On the other hand, the younger respondents seemed to be opposed to several harmful traditional practices affecting women, including dokhla baladi (virginity testing), and expressed more support than the older respondents for girls' education and women's work.

Discussion and recommendations

This study points to certain key issues that need to be taken into consideration in future interventions, starting with the gendered way in which sexuality is constructed by both women and men, and influenced not only by their personal experience, but also by their socioeconomic situation. In a 2007 study in Egypt,Citation37 women related their sexual problems most often to socioeconomic circumstances. Like the women in our study, many reported that they engaged in sexual activity for marital commitment, religious and financial reasons, and to reduce the risk of husbands engaging in extramarital relationships.

Some of the men in our study, especially the younger ones, perceived that FGM/C could have negative effects on women's sexual response; this was not unexpected since many tended to equate sexual pleasure with the physical aspects of sexual relations. They are then more likely to blame “the missing parts” for any sexual dysfunction women might be experiencing. Men are thus in a quite equivocal position – on the one hand concerned that women's pleasure in sex is reduced, thus hindering their own pleasure, and on the other hand worried that uncircumcised women will be too sexually demanding, endangering their control over the sexual relationship.

The expressions of resistance to political interventions imply that, although important, the newly introduced legislation alone may not be able to stop the practice. As people consider female genital mutilation/cutting to be key to women's sexual morality, educational measures will also be needed. Experience from interventions in both Egypt and other countries suggest that political commitment must be combined by strong advocacy and education programmes at both national and community levels, within a package of education and training to eliminate other harmful traditional practices, such as early marriage and domestic violence.Citation34Citation37 A developmental approach is also needed within this, in which women are empowered and their position in the family is improved.

Most Egyptians are avid TV watchers, and keen on movies and drama. TV, radio, newspapers, drama and soap operas could well be used for educational messages against female genital mutilation/cutting. Information that could counteract the association between the clitoris, sexual desire and “immoral” behaviour in women could have an important effect.

It seems paramount also to include these perspectives in the training of health care providers and those involved in interventions against the practice in Egyptian communities. Health care providers should also be trained in sexuality counselling, so as to be able to deal with sexual problems that may or may not be related to female genital mutilation/cutting. In addition, those personnel expected to enforce the law, such as police, attorneys and social workers, need to be made aware of these issues.

We recognize however, that the inclusion of these perspectives on FGM/C and sexuality must be handled with care, as this is a quite sensitive subject in Egypt.

The changes we found among the younger generation of our respondents in opposing several harmful traditional practices, and their greater support for girls' education and women's work, indicate a more favourable environment for empowering women and consequently some hope for the abandonment of female genital mutilation/cutting in the future.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development, and Research Training in Human Reproduction, World Health Organization. Many thanks to R Elise B Johansen, whose editorial support was invaluable. Thanks are also due to all the NGOs the team has worked with: The Cairo Family Planning and Development Association, Al-Khashaba Association for Development, St Mark for Development Association, and the Association for the Development and Enhancement of Women. The Cairo Family Planning and Development Association managed the financial and administrative parts of the study. The research team is indebted to the two research assistants who helped tremendously with collecting the data and the process of transcription: Mrs Naglaa Fathy and Mr Mohamed Darwish. Many thanks also to Dr Shereen El Feki for valuable remarks and assistance and editing the final report.

Notes

* For the physiological evidence supporting that assumption, see: Federation of Feminist Women's Health Centers. A New View of a Woman's Body. Feminist Press, USA, 1991.

References

- F El-Zanaty, A Way. Egypt Demographic & Health Survey. 2008; National Population Council; Ministry of Health and Population.

- F El-Zanaty, A Way. Egypt Demographic & Health Survey. 2000; National Population Council; Ministry of Health and Population.

- TM Eldin, M Gadalla, M El-Tayeb. Prevalence of female genital cutting among Egyptian girls. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 86: 2008; 269–274.

- O El-Gibaly, B Ibrahim, B Mensch. The decline of female circumcision in Egypt: evidence and interpretation. Policy Research Division Working Paper. 1999; Population Council: Cairo.

- Eliminating female genital mutilation. An interagency statement. 2008; WHO: Geneva.

- Egyptian Fertility Care Society. Clinic-based investigation of the typology and Self-reporting of FGM in Egypt. Final Report, November 1996.

- AA Hadi, SA Salam. Physicians' attitudes towards female circumcision. 1999; Cairo Institute for Human Rights: Cairo.

- A Ragab. Some ethical considerations regarding medicalization of female genital mutilation/cutting. Bioetica Journal. 8: 2008; 10–13.

- Global strategy to stop health-care providers from performing female genital mutilation. 2010; WHO: Geneva.

- F El-Zanaty, A Way. Egypt Interim Demographic & Health Survey. 2003; National Population Council; Ministry of Health and Population.

- AG El-Serour, A Ragab. Towards the eradication of female circumcision, questions and answers of religious scholars. 2005; UNICEF: Cairo.

- El Awa S. Female circumcision from an Islamic perspective. Monograph. National Council for Childhood and Motherhood, undated.

- A Ragab, AG el-Serour. Towards a comprehensive and alternative vision for eradicating female genital mutilation. 2003; WHO: Cairo.

- National Council for Childhood and Motherhood. Documentation of the FGM Free Village Model Project, Summary Report, 2008.

- Ministry of Health. Decree No. 271, 2007.

- Egypt Penal Code, close 242 bis, 2008.

- N El-Sadawi. The Hidden Face of Eve. 1980; Zed Books: London.

- L Abu Lughod. The romance of resistance: tracing transformations of power through Bedouin women. American Ethnologist. 17(1): 1990; 41–55.

- S Ortner. Borderland politics and erotics: gender and sexuality in Himalayan mountaineering. B Ortner. Making Gender: The Politics and Erotics of Culture. 1996; Beacon: Boston, 181–212.

- J Clark. State of desire: transformations in Huli sexuality. L Manderson, J Margaret. Sites of Desire/Economics of Pleasure. 1997; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 191–211.

- N Toubia. Female Genital Mutiliation: A Call to Global Action. 1993; Women Ink: New York.

- J Whitehor, O Ayonrinde, S Maingay. Female genital mutiliation: cultural and psychological implications. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 2: 2002; 161–170.

- BC Ozumba. Acquired genestresia in Eastern Nigeria. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 37: 1992; 105–109.

- F Ahmadu. Rites and wrongs: an insider/outsider reflects on power and excision. B Shell-Duncan, Y Hernlund. Female ‘Circumcision’ in Africa: Culture, Controversy and Change. 2000; Lynne Rienner: Boulder, 283–312.

- F Ahmadu. “Ain't I a woman too?”: challenging myths of sexual dysfunction in circumcised women. Y Hernlund, B Shell-Duncan. Transcultural Bodies: Female Genital Cutting in Global Context. 2007; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick.

- Dellenborg L. Multiple meanings of female initiation. “Circumcision” among Jola women in Lower Casamance, Senegal. PhD dissertation, Department of Social Anthropology, Göteborg University, 2007.

- JL Fourcroy. Customs, culture and tradition: what role do they play in a woman's sexuality?. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 3: 2006; 954–959.

- CM Obermeyer. The consequences of female circumcision for health and sexuality: an update on the evidence. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 7: 2005; 443–461.

- CM Obermeyer, R Reynolds. Female genital surgeries, reproductive health and sexuality. Reproductive Health Matters. 7(13): 1999; 112–120.

- H Stewart, L Morison, R White. Determinants of coital frequency among married women in Central African Republic: the role of female genital cutting. Journal of Biosocial Sciences. 34: 2002; 525–539.

- H Khattab. Women's Perceptions of Sexuality in Rural Giza. Monographs in Reproductive Health No.1. 1996; Population Council: Cairo.

- M Karim, R Ammar. Female Circumcision and Sexual Desire. 1965; Ain Shams University Press: Cairo.

- RM Abd El-Hady, AB El-Nashar. Long-term impact of circumcision on health of newly married females. Zagazig University Medical Journal. 6: 1998; 839–851.

- MH El-Defrawi, G Lotfy, KF Dandash. Female genital mutilation and its psychosexual impact. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 27: 2001; 465–473.

- SMA Thabet, ASMA Thabet. Defective sexuality and female circumcision: the cause and the possible management. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecological Research. 29: 2003; 12–19.

- M El-Rabbat. A critical review of studies investigating the adverse effect of FGC with particular reference to type I & II prevalence in Egypt. 2003; Egyptian Fertility Care Society: Cairo.

- A El Nashar, M El-Dien, M El-Desoky. Female sexual dysfunction in Lower Egypt. BJOG. 144: 2007; 201–206.

- RC Berg, E Denison, A Fretheim. Psychological, social, and sexual consequences of female genital mutilation/cutting: a systematic review of quantitative studies. Report No.13. 2010; Kunnskapssenteret: OsloAt: <http://www.kunnskapssenteret.no/Publikasjoner/9555.cms?language=english&threepage=1>. Accessed 15 October 2010

- Female Genital Mutilation/Female Genital Cutting: a Statistical Exploration. 2005; UNICEF: New York.

- FE Okonofua, U Larsen, F Oronsaye. The association between female genital cutting and correlates of sexual and gynaecological morbidity in Edo State, Nigeria. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 109(10): 2002; 1089–1096.

- Meston CM, Buss DM. Why Women Have Sex: Understanding Sexual Motivations from Adventure to Revenge (and Everything in Between). Times Books, 2009.