Abstract

In Bangladesh, the formal public health system provides few services for common sexual and reproductive health problems such as white discharge, fistula, prolapse, menstrual problems, reproductive and urinary tract infections, and sexual problems. Recent research has found that poor women and men resort to informal providers for these problems instead. This paper draws on interviews with 303 providers and 312 women from two rural and one urban area of Bangladesh from July 2008 to January 2009. Both informal and formal markets played an important role in treating these problems, including for the poor, but the treatments were often unlikely to resolve the problems. Providers ranged from village doctors without formal training to qualified private practitioners. The health system is heavily marketised and boundaries between “public” and “private” are blurred. There exists a huge, neglected domain of sexual and reproductive health needs which are a source of silent suffering and for which there are no trained health staff providing treatment in government facilities. The complexity of this situation calls for engaged debate in Bangladesh on how to improve the quality of existing services, discourage or prevent obviously harmful practices, and develop financing mechanisms to enable women to access effective treatment, regardless of the source, for these neglected problems.

Résumé

Au Bangladesh, le système de santé officiel s'occupe peu des affections de santé génésique courantes, comme les pertes blanches, les fistules, les prolapsus, les problèmes menstruels, les infections de l'appareil génital et urinaire et les troubles sexuels. Des recherches récentes ont révélé que les femmes et les hommes pauvres s'adressent à des prestataires informels pour ces problèmes. L'article se fonde sur des entretiens avec 303 prestataires et 312 femmes de deux zones rurales et d'une zone urbaine du Bangladesh, de juillet 2008 à janvier 2009. Les marchés formels et informels jouaient tous deux un rôle important, notamment pour les pauvres, mais les traitements avaient peu de chances de résoudre ces problèmes. Les prestataires allaient de médecins villageois sans formation officielle à des praticiens privés qualifiés. Le système de santé est fortement influencé par les lois du marché et les frontières entre le « public » et le « privé » sont floues. Il existe un vaste domaine négligé de besoins de santé génésique qui sont une source de souffrances silencieuses et pour lesquels on ne dispose pas de personnel de santé formé à traiter les patientes dans les centres gouvernementaux. La complexité de la situation nécessite un débat engagé au Bangladesh pour trouver comment améliorer la qualité des services, décourager ou prévenir les pratiques manifestement dangereuses et créer des mécanismes de financement qui donneront accès aux femmes à un traitement efficace, quelle qu'en soit la source, de ces problèmes oubliés.

Resumen

En Bangladesh, el sistema oficial de salud pública ofrece pocos servicios para problemas comunes de salud sexual y reproductiva como secreción blanca, fistula, prolapso, problemas menstruales, infecciones del tracto reproductivo y de las vías urinarias y problemas sexuales. En recientes investigaciones se ha encontrado que las mujeres y los hombres pobres recurren a prestadores de servicios extraoficiales para resolver estos problemas. Este artículo se basa en entrevistas con 303 prestadores de servicios y 312 mujeres de dos zonas rurales y una urbana, en Bangladesh, desde julio de 2008 hasta enero de 2009. Ambos el mercado oficial y el extraoficial desempeñaron un papel importante para tratar estos problemas, incluso para gente pobre, pero a menudo resultó improbable resolver los problemas con sus tratamientos. Entre los prestadores de servicios figuraban desde médicos del pueblo sin formación académica hasta practicantes particulares calificados. El sistema de salud es muy comercializado y la línea divisoria entre los sectores “público” y “privado” es borrosa. Existe una enorme gama de necesidades desatendidas de salud sexual y reproductiva que son una fuente de sufrimiento silencioso y para las cuales no hay personal de salud capacitado ofreciendo tratamiento en unidades gubernamentales. Esta compleja situación en Bangladesh requiere un debate abierto sobre cómo mejorar la calidad de los servicios actuales, impedir o poner freno a las prácticas obviamente dañinas y crear mecanismos de financiamiento para que las mujeres tengan acceso a tratamientos eficaces, independientemente de la fuente, para estos problemas desatendidos.

Over the last two decades increasing international attention has been focused on women's sexual and reproductive health as a priority area for health care reform.Citation1 The UN's commitment to universal access to reproductive health by 2015 through Millennium Development Goal 5 on maternal health, has added to the impetus. In Bangladesh, sexual and reproductive health remains an area of concern in the context of meeting the MDGs in health and women's empowerment.Citation2 In spite of the fact that the global maternal mortality ratio has declined from nearly 574 per 100,000 live births in 1990 to 340 in 2008.Citation3 However, maternal deaths in Bangladesh remain very high. An estimated 14% of them are caused by violence during pregnancy, and a study in 1996–97 estimated that 26% of all maternal deaths were a result of complications of unsafe abortions, performed by untrained birth attendants through the insertion of a foreign object into the uterus, most commonly a root or stick. Some 45% of all mothers are malnourished. Nearly half of adolescent girls (15–19 years) are married, and 57% of them (or 28.5% of the total) become mothers before the age of 19, half of whom are acutely malnourished (14.25% of all adolescent girls).Citation4 A World Bank study found a high burden of reproductive morbidity in developing country women aged 15–44 years, about one-third of the disease burden. Available data for South Asia showed that women have a huge unmet need for services relating to these conditions.Citation5 A 1999 survey on morbidity due to reproductive tract infection (RTI) among users and non-users of family planning showed that 22% of 2,929 rural women of Bangladesh reported symptoms of infection. Of 472 symptomatic women examined, 68% had clinical or laboratory evidence of untreated infection, which may cause infertility or congenital neonatal syphilis or gonococcal eye disease.Citation6 In 2003, an estimated 8.76 million Bangladeshi women were suffering from chronic morbidity due to vesico-vaginal and recto-vaginal fistula, uterine prolapse, dyspareunia, haemorrhoids and associated physical and social disabilities. Poor, illiterate women aged 15–30 years were the most affected. They were often unaware of the limited treatment available or could not access or afford it, as there are very few trained professionals providing services for these conditions, particularly for fistula and prolapse.Citation7

In Bangladesh, the formal public health system provides few services for sexual and reproductive health problems. Little attention has been paid to informal medical markets and providers in Bangladesh, yet recent empirical research in both rural and urban areas reveals that poor women and men resort to informal providers for a range of these problems. Bangladesh is facing an increasing demand for health services, unmatched by supply, particularly in the public sector. In 2008 a national survey of informal and formal providers found that there were only 0.58 qualified health workers for every 1,000 population, far short of the optimal 2.5 per 1,000 recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), and with only 16% located in rural areas.Citation8 Bangladesh's existing health workforce faces mounting challenges, including staff shortages and maldistribution, particularly of professional staff reluctant to work in rural areas, skill mix imbalances, a negative work environment and weak knowledge base.Citation9 This particularly affects maternal and other SRH services as they are heavily dependent on both professional and lower-tier providers. It is estimated that over 85% of the population are treated by informal health care workers, who fill the gap between supply and demand.Citation9

Informal health care workers operate outside the formal rules regulating the practice and conduct of health staff, as laid down by the Bangladesh Government in 2000.Citation10Citation11 Several regulatory and statutory bodies exist in order to develop qualified health professionals, ensure standard health services to the people and protect their rights. However, most of these bodies are non-functional and lack accountability, which has allowed the informal and private sectors to flourish and all sectors, including the formal, to remain unaccountable for quality of care.Citation12

Informal providers vary significantly according to their knowledge and the position they hold in the broader health market/supply chain.Citation13 Non-graduates, usually informally trained allopathic practitioners (also referred to as village doctors, pharmacists or drug sellers) and traditional healers greatly outnumber certified health care providers. There are an estimated 180,000–284,000 village doctors who outnumber certified MBBS physicians 12 to 1.Citation11Citation14Citation15 Village doctors often practise at the numerous unregistered pharmacies located across the country, making diagnoses and dispensing medicines. Conservative estimates in 2005 found at least 62,000 unregistered pharmacies in the country.Citation16 In addition, an estimated 70–75% of Bangladeshis use traditional healersCitation17 or homeopathic practitioners. An estimated 31 traditional healers and 33 homeopaths per 10,000 population are practising in the country.Citation9

Services offered by informal providers are mainly curative in nature. They take medical histories, make diagnoses and prescribe biomedicines and/or herbal remedies.Citation10 Common medical problems treated by them include pneumonia, diarrhoea, hypertension and reproductive and sexual health problems. Traditional healers and village doctors commonly advise on family planning methods, pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). It is estimated that a majority of people suffering from STIs are treated by medicine sellers.Citation18

Bangladesh's public health services are hierarchically structured from the national to the village level and centralised in terms of decision-making and financing. Hospitals, health centres and clinics provide services from tertiary to district to primary level, with the workforce correspondingly organised. Civil surgeon, upazilla (district) health and family planning officer, junior consultant, resident medical officer and medical officer are all general physician posts. Paramedical positions from sub-district level downwards are upazilla family planning assistant, family welfare visitor, health inspector, medical assistant, sub-assistant community medical officer, pharmacist, medical technologist, family welfare assistant, health assistant and skilled birth attendant.Citation19 Studies have consistently noted problems with the quality of public health services, including poor provider attitudes and lack of availability of drugs and serviceable equipment, which have led to underutilisation of government services and contributes to high levels of use of informal and other private services.Citation9Citation12

We use the term “private sector” to cover all transactions not directly provided by government. This includes formal and informal providers and a significant number of not-for-profit NGO services.Citation20 Since the 1950s, private practice by public sector physicians has also been taking place, partly because of the small number of private sector physicians and partly for government physicians to augment their incomes. No clear policy covers this practice.Citation21 The Fifth Five-Year Plan reported that “a large number of government-employed doctors carry on private practice in the health sector” (p.481).Citation22 One study reported that 33% of doctors with an MBBS degree and 51% of public sector specialists are involved in private practice.Citation20Citation23 Paramedics and other support staff (e.g. community medical officers, medical assistants, nurses and pharmacists) also cross the public–private boundary, offering services (including diagnostics) outside their regular working hours at private clinics, earning money on the side, while also in government service.Citation20

Methodology

The study covered both women's and men's sexual and reproductive health problems and use of providers. Due to the very large amount of data, this paper focuses on the 312 ever-married women aged 15–49 who were interviewed. We used a pre-tested questionnaire with both closed and open questions. It covered at least 100 female respondents from each of three selected sites: Chittagong (urban), Rangpur (rural) and Sylhet (rural), which were chosen to represent a range of different poor populations in Bangladesh. Respondents from Chittagong (a port city) lived in a typical urban slum. Those from Rangpur represented the ultra-poor from an area repeatedly affected by seasonal food insecurity. Those from Sylhet represented the rural poor to moderately poor from a conservative religious area.

Five female data collectors worked with the research staff supervisor in three phases from July 2008 to January 2009. The questionnaire generated information on socio-demographic status; women's knowledge of contraception, maternal health and abortion; community sexual and reproductive health problems, their causes and perceived severity; personal experience of sexual and reproductive health problems within the last 12 months; health-seeking history; and the providers used. In free listing of perceived sexual and reproductive health problems, none of the women referred to contraception or maternal health but to other problems, including menstrual irregularities, prolapse, fistula, infertility, burning/itching in the genital region, STIs, body aches and concerns about sexual desire. Therefore we created four sections in the questionnaire, the first and largest part on general sexual and reproductive health problems, as identified by them, the second on contraceptive knowledge and practice, a smaller third section on maternal health, and a fourth section on abortion (services sought, whether legal and illegal, costs).

We gained access to the communities through political, religious and youth leaders such as the ward commissioners, chairmen of the Union Parishad (the smallest unit of local government), local leaders of the ruling political parties and various community leaders. We also spent time speaking to local traditional birth attendants and different types of health workers, who made it easier for us to gain access to women in the community.

Respondents were selected from every fifth household (in the rural settings) or tenth household in Chittagong, due to high household density. Selection was done from the first household of the given entry point in each case. We assigned one data collector per zone, to avoid selecting two or more respondents from the same household or people who would be well known to each other, given the sensitivity of the topics.

Informed consent was obtained from all respondents before the survey and in any subsequent follow-up, and it was made clear that participation was entirely on a voluntary basis and they could withdraw at any time. Parental or husband's consent was also obtained where needed. Interviews were conducted in a place convenient for the interviewee without the presence of friends, neighbours or family members. No financial or material incentives were given. The study received ethical clearance from the BRAC University independent Ethical Review Board.

To cross check the integrity of the data, re-interviews were conducted with 5% of randomly selected respondents. These validated most of the data collected. Privacy and confidentiality were assured by maintaining anonymity and protecting the data in a locked cabinet. There was a 2% refusal rate. Following the questionnaire survey, we selected 63 respondents (22 from Chittagong, 17 from Rangpur and 24 from Sylhet for in-depth interview to questions on sexual and reproductive health, use of services for any problems, severity of reported problems and treatment-seeking history. Where appropriate or requested, we referred women to facilities certified by BRAC, one of Bangladesh's largest NGO providers of health services.

Data collectors were given intensive training and time to familiarise themselves with their area. They were asked to identify local terms that were used for the standard Bengali terms in the survey. Data from in-depth interviews were manually coded and analysed, with attention to repetitive themes and issues raised, patterns in responses and unusual findings.

To capture all providers of sexual and reproductive health services in the three sites, a list of 925 providers was generated from a detailed geographical mapping and from information about providers reported in surveys in the rural sites and one section of the urban site. The mapping found 925 active providers treating sexual and reproductive health conditions, of whom 560 were individual male providers and 311 were individual female providers. The remainder (5.9%) were various clinics/hospitals/organisations providing sexual and reproductive health services.

303 providers were selected for interview from the 925 found through mapping, at least 100 from each study site, of whom 5% were re-interviewed as a quality check and 44 for in-depth interview. The sample covered every type of provider and location, including qualified doctors, homeopaths, government hospitals, NGO clinics, private clinics, village doctors (or rural medical practitioners) faith healers, herbalists, family planning workers, medical assistants, health assistants, pharmacists, drug sellers, traditional and skilled birth attendants, and street-based medicine sellers. We ensured that there was representation of each type of provider found; providers were then sampled proportionately (which varied site to site) based on their total numbers, to balance the ratio of each type of provider. The team explained the nature of the study and reassured them of anonymity and confidentiality. Data collectors wore an official University identity card to clarify that they were not police or journalists investigating malpractice, which was effective in gaining trust.

Findings

Socio-demographic profile of the women

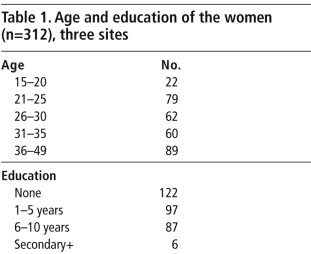

The average age of the respondents was 30.8 years. Almost 40% had received no education (Table 1

). They were married an average of 14 years; 28.5% had married by age 15 and 70% had married before reaching 18. In Bangladesh early marriage is the only acceptable option for poor adolescent girls, and in poor families marriage usually takes place soon after a girl menstruates or one to two years afterwards. The legal age of marriage is 18 years for girls and 21 years for boys.Citation24The women's average monthly household income was Taka 7,105 (=US$104). However, 25% of the women and their families were in the lowest income quintile, earning less than Taka 3,000 (US$43) per month and of these, almost half were from Rangpur, the poorest of the three sites, which had the lowest average per capita income (US$70).

87% of the women did not work outside the home, 3% reported holding private or government jobs, and the remaining 10% were involved in small-scale activities such as tailoring or other micro-enterprises (selling food and livestock), rearing animals, day labouring or domestic service.

Most commonly reported sexual and reproductive health problems

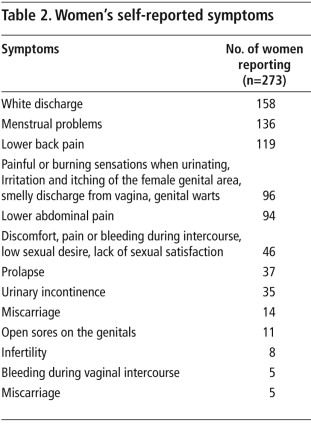

To reduce the sensitivity of the issue and enable the interviewer to build rapport, all the women were first asked to describe what they considered to be the most common female SRH problems in their communities. Over 90% mentioned white discharge, lower abdominal and back pain, infertility, miscarriages and excessive menstrual bleeding. Over 80% mentioned reduced menstrual bleeding, irregular menstruation and the impact and consequences of abortion on their health. Women were vigilant about monitoring blood loss during menstruation as this was perceived to signify fertility. Most of the problems mentioned are medically neglected reproductive health conditions in Bangladesh, given the focus of the health sector on family planning and maternity services. Women were then asked about their own specific health problems (Table 2

).These self-reported problems were similar to the list of common problems provided by the women. It is noteworthy that women reported suffering from SRH problems that are often not discussed openly due to shame or stigma, such as low sexual desire, genital sores and warts, smelly discharge, infertility and bleeding during sexual intercourse.

Who were the providers?

Of the 303 individual providers surveyed from the three areas, 62% were male and 38% female. The average age was 46 years and average years of experience 17.6 years. 25% reported having institutionally recognisedFootnote* degrees and medical training; 63% had not received any formally recognised training but claimed they learned by working with their employers or receiving guidance from others. The remaining 12% said they had no training, formal or informal.

In terms of education, 44 providers claimed to hold a Masters of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery degree, while 40 reported studying up to Bachelor or Masters degree level. 104 reported completing 10–12 years of education. 66 had studied below Class 10, and 49 of the surveyed providers did not have any formal education at all. Providers reported obtaining their knowledge and skills from a range of sources; from formal medical training, inspirational or dream-based learning, that is, a series of dreams where they found information about healing, or inherited from family members (many perceived this profession as an ancestral gift or inherited healing as a family tradition), religious books, or learned by working closely with relatives or colleagues or by observing.

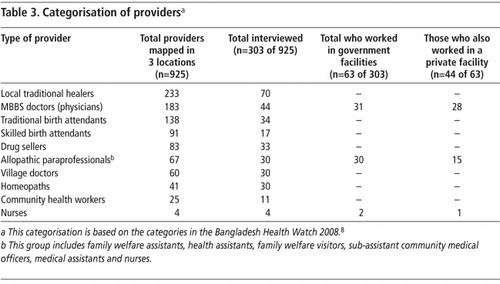

Across the range of providers, many working in the public sector also operated as market-based independent providers. Many developing country health systems are now heavily marketised and the boundaries between “public” and “private” provision have become increasingly blurred as government health workers often set up their own independent practices alongside their public facility jobs.Citation25 This is the case in Bangladesh, where staff at all levels may have private patients, work in a variety of arrangements (see Table 3

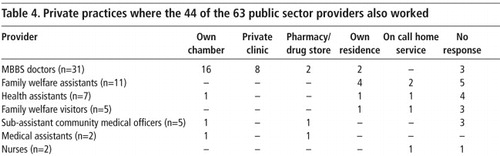

) and charge a fee for their services.Table 3 shows the type and number of the 303 providers and how few were employed in a public facility. The low number of nurses (1.3%) is noteworthy and mirrors the situation in the country. For the country as a whole there are around five physicians and two nurses per 10,000 population, with a very low nurse-to-physician ratio of 0.4; whereas the acceptable standard is two or three nurses for each doctor.Citation9 Of the 303 providers, only 63 (20.8%) were employed in a public facility but were also practising privately (Table 4

). None of the skilled birth attendants in the survey were affiliated with public facilities although they were trained under a government initiative.Of the 63 providers who worked in public facilities, 44 also worked in the private sector. Table 4 shows where these 44 public sector providers also practised privately. This information is significant for understanding the high absenteeism of providers in public sector workplaces, especially MBBS doctors, and the importance of public sector doctors and others as major players in the private health sector.

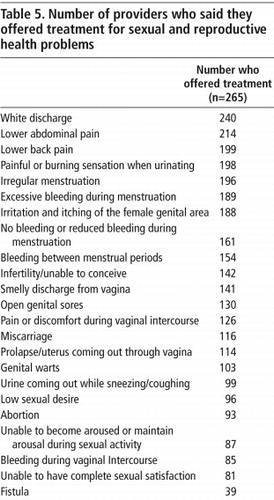

shows the responses of the 265 providers (of the 303 interviewed) who said they provided treatment for the sexual and reproductive health problems women reported experiencing.Of those who reported being willing and able to treat both men and women suffering from sexual and reproductive health conditions, 88 said they provided services only to female patients, while 177 offered treatment to both men and women. Providers also reported that many women are prepared to visit a male provider for treatment. Among the 188 male providers surveyed, five provided services to women only while 145 treated both men and women. The remaining male providers (20.2%) provided services to men only. This finding is counter to the role of pardah (seclusion of women and segregation of the sexes among Muslims in South Asia) and associated reluctance to visit male health care providers.Citation26Citation27

“My sister-in-law said, if you want to live… go and see that [male] doctor, so I visited him, sacrificing my shyness and status…” (Rural woman, 32 years old)

Women seeking treatment for sexual and reproductive health problems: the role of providers

In the surveys women were asked to rank the most preferred type of providers in their localities to consult for sexual and reproductive health problems. Of the 101 women in Rangpur, 27% mentioned village doctors and pharmacists as the most preferred, 13% thought it was homeopaths and 10.9% mentioned family planning workers. Less than 10% mentioned MBBS doctors. In Sylhet, of the 109 women surveyed, 53% ranked village doctors and pharmacists as the most preferred, with 28.4% ranking MBBS doctors as the most preferred, followed by faith healers (12.8%). In Chittagong (urban), in contrast, 37% of the women ranked MBBS doctors as the most preferred, followed by government hospitals (25.5%), while just 12.7% ranked village doctors and pharmacists as the most preferred. We did not ask whether consultations with MBBS doctors took place in the public or private sector but we infer that they took place privately. This is because during the survey and in-depth interviews, when women said they had visited a hospital or community clinic they reported it as such, but when they visited a privately practising medical doctor, they reported him/her as an MBBS doctor.

Of the total sample of women, 65% reported taking allopathic drugs for their conditions, 35% reported taking herbal medicines/plants and drinking enchanted water, making a sacrifice and/or wearing amulets to cure their illnesses, while just under 10% reported taking homeopathic medicines as treatment.

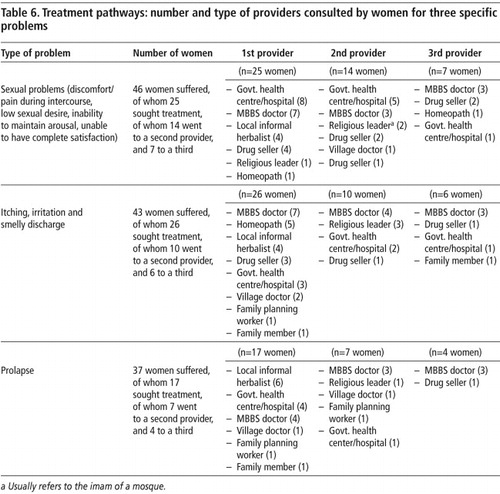

provides information on the treatment pathways of women who sought care for sexual problems, smelly and irritating discharge, and prolapse. While some women relied on only one provider, a significant number resorted to a second or third provider for treatment, implying that the first (and in fewer cases the second) had not successfully treated the problem. For the sexual problems described in Table 6, treatments that the 265 providers said they prescribed for improving sexual function ranged from vitamins, tablets and herbal tonics (36.6% of providers), to medicinal plants (10% of providers), amulets (6.2%) and massage creams and oils (3%).This table shows that the treatment-seeking behaviour of women ranged across the spectrum of provider types for each problem and with no systematic pattern. Provider reputation played a major role in treatment-seeking decisions. Women often came to know about a provider from discussions among their peers and neighbours and would be advised to visit particular providers for specific ailments. A combination of factors influenced reputation. These included the length of time providers had been working in the community, the fact that the provider was from the locality and followed up with them, and that it was easier to share their concerns because of the cultural familiarity of the problem. Many providers also waived regular fees, allowing women credit or to pay in kind (e.g. food). Similarly, many providers emphasised that they would follow up patients in the marketplace or the village, or even visit them at home. The absence of class differences and the social proximity of local informal providers and, in particular, flexibility on payment, were an incentive to poor women, who were already constrained by restricted mobility and lack of earning power. The lack of hierarchy and existing social relationships in the locality made informal providers more accessible. This was more the case in the rural areas, where informal providers, particularly drug sellers/pharmacists were preferred. In contrast, in urban Chittagong, the significantly greater reported use of qualified doctors reflected their greater availability and accessibility.

Treatment costs

Out of 312 women surveyed, 273 reported that they had suffered or were suffering from at least one or more sexual and reproductive health problem during the last 12 months. Of those 273 women 152 reported that they had consulted a provider and spent an average of Taka 2,374 (US$34) on treatments for the last problem(s) they suffered. The average cost for each woman out of the 152 women who received services from MBBS physicians was Taka 2,527 (US$37) and from the government health centres was Taka 1818 (US$26). This included all costs (i.e. fees, transport, diagnostic, medicines, etc).Footnote* Respondents mentioned that the actual total charges for access to government facilities should be approximately costing Taka 10 (less than US$1), which included medicines and consultation but in reality, women reported they did not receive the required medicines and had to pay separate additional money for medicines. To visit a private doctor the fee ranged from Taka 50 to 600 (US$1–9). Women visiting informal providers such as drug sellers usually paid for the medicines taken. However, if they saw a doctor who worked in the pharmacy, they would pay a minimum fee of Taka 50 (less than US$1). With traditional healers, payment was usually based on the relationship with the healer; this could include gifts in exchange for services and/or money for medicines. The average amount spent by the respondents for services from herbal medicine practitioners and for birth attendants (skilled and traditional) was Taka 1109 (US$16) and Taka 137 (US$2), respectively. Respondents did not report the cost of any gifts (if provided).

Respondents were asked about the source of the expenditure for treating their last sexual and reproductive health problem(s). Among the poor women, 83.5% used money from family income. Only 40 of the 312 women worked outside the home and had independent earnings. This meant negotiating with husbands or secretly using money meant for daily marketing. 13.8% mentioned using savings, while 13% took loans from relatives. 5.2% got loans from local money lenders, incurring huge interest, and 2% mentioned selling assets to pay for treatment.Footnote†

Conclusion

In this paper we have examined what sexual and reproductive health problems women in poor rural and urban areas of Bangladesh experience and what kinds of providers they use for these problems. Our survey found that women and men spend considerable amounts of money on SRH providers, both formal and informal, with unclear quality of care or benefit. Some of this expenditure was on perceived sex-related problems, dealt with by a wide range of culturally-grounded informal specialists. We found in general that services for sexual and reproductive health problems are provided in large part through a diverse informal market. Furthermore, the majority of formal providers were involved in private practice and only in some cases also in public practice. This “market” is not neatly divided between what is public and what is private. The boundaries between the two are porous, in both sanctioned and unsanctioned ways. Overall, the health system accommodates multiple forms of practice, with varying degrees of legitimacy. Women do not choose providers because they are “public” or “private” but by reputation, cost and accessibility.

Women need the family planning and maternal health services that are provided through the government system,Citation28 but all their other sexual and reproductive health problems are poorly catered for in the public system, leaving a vacuum that has been filled primarily by unregulated, informal practitioners. These findings highlight the gap between what women seek services for and what is provided through the government health system. There exists a huge, neglected domain of sexual and reproductive health needs which are a source of silent suffering and for which there are no formally provided services or trained health staff in government facilities. Given the resource and personnel constraints in Bangladesh, this gap will not be filled by the public health sector in the near future. The complexity of this situation calls for engaged debate in Bangladesh on how to improve the quality of existing services, discourage or prevent obviously harmful practices and develop financing mechanisms to enable women to access safe and effective sexual and reproductive health services, regardless of their source.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the financial support for this research (Grant No.HD43) of the UK Department for International Development to the Realising Rights Research Programme Consortium. The views expressed are the authors' alone. We also acknowledge the support of Dr AMR Chowdhury, Dr Kaosar Afsana, advisors to the project, and Ilias Mahmud for his contribution to the initial data collection in Chakaria. We also thank the research assistants, without whom this research would not have been possible.

Notes

* This includes only medical degrees such as MBBS (Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery, Bachelor of Dental Surgery (BDS) and Medical Assistant training (MATS) approved by the Bangladesh Medical and Dental Council).

* In the questionnaire women were asked about the following costs incurred: transport, diagnosis, service charge, medicines.

† Here we asked respondents to mention sources of expenditure.

References

- J DeJong. The role and limitations of the Cairo International Conference on Population and Development. Social Science & Medicine. 51(6): 2000; 941–953.

- World Bank. Bangladesh: From Counting the Poor to Making the Poor Count. 1999; World Bank Publications.

- Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2008. At: <http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241500265_eng.pdf. >. Accessed 30 January 2011.

- National Institute of Population Research and Training. Bangladesh Maternal Mortality Survey, Dhaka, 2001.

- Pachauri S. Unmet reproductive and sexual health needs in South Asia. Journal of Health & Population in Developing Countries. 1(2): 1998; 29–39.

- Mitra and Associates. Urban Family Health Partnership Baseline survey, Dhaka, 1999.

- EngenderHealth Bangladesh. Situation analysis of obstetric fistula in Bangladesh. Dhaka, 2003.

- Bangladesh Health Watch. Health Workforce in Bangladesh: Who Constitutes the Healthcare System. Dhaka, 2008.

- Joint Learning Initiative. Human Resources for Health: Overcoming the Crisis. 2004; Harvard University Press: Boston.

- F Omaswa. Informal health workers: to be encouraged or condemned?. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 84(2): 2006; 83.

- World Bank. Private sector assessment for Health, Nutrition and Population in Bangladesh. Report No.27005-BD. World Bank, 2003.

- Bangladesh Health Watch. How healthy is health sector governance? Dhaka, 2010.

- L Conteh, K Hanson. Methods for studying private sector supply of public health products in developing countries: a conceptual framework and review. Social Science & Medicine. 57(7): 2003; 1147–1161.

- R Aziz, M Gautham, O Oladepo. Making health markets work for poor people: improving provider performance. ID21 Insights. 76: 2009; 3.

- International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research. Quality of informal healthcare providers in rural Bangladesh: implication in the future health system. 2009; ICDDR,B: Dhaka.

- Bangladesh Public Policy Watch. Millenium Development Goals: A Reality Check. 2005; Unnayan Onneshan: Dhaka.

- MS Islam, SS Farah. How complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is promoted in Bangladesh: a critical evaluation of the advertisements published in local newspapers, Internet. Journal of Alternative Medicine. 5(2): 2008; 2.

- SM Ahmed. Informal sector providers in Bangladesh: how equipped are they to provide rational health care?. Health Policy and Planning. 24: 2009; 467–478.

- Primary health care service: transparency and accountability. At: <www.studycirclebangladesh.info/admin/publication/2007041172_photo.pdf. >. Accessed 28 April 2010.

- M Rahman. The state, the private health care sector and regulation in Bangladesh. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Administration. 29(2): 2007; 191–206.

- Khan MM. Role of private markets in the health sector of Bangladesh: some preliminary discussions. Paper presented at seminar of Centre for Development Research, Dhaka, 1995. (Unpublished)

- Government of Bangladesh. Fifth Five Year Plan 1997–2002. 1998; Planning Commission: Dhaka.

- ORG-Marg Quest. Report on medical practitioners and pharmacists in Bangladesh. Prepared for NICARE/British Council. Dhaka, 2000.

- National Institute of Population Research and Training. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2007. Dhaka, 2009.

- G Bloom, H Standing, R Lloyd. Markets, information asymmetry and healthcare: towards new social contracts. Social Science & Medicine. 66(10): 2008; 2076–2087.

- S Islam. The socio-cultural context of childbirth in rural Bangladesh. M Krishnaraj, K Chanana. Gender and the Household Domain: Social and Cultural Dimensions. 1989; Sage Publications: New Delhi.

- M Paolisso, J Leslie. Meeting the changing health needs of women in developing countries. Social Science & Medicine. 40(1): 1995; 55–65.

- MK Mridha, I Anwar, M Koblinsky. Public-sector maternal health programmes and services for rural Bangladesh. Journal of Health Population and Nutrition. 27(2): 2009; 124–138.