Abstract

This paper presents findings on hysterectomy prevalence from a 2010 cross-sectional household survey of 2,214 rural and 1,641 urban, insured and uninsured women in low-income households in Ahmedabad city and district in Gujarat, India. The study investigated why hysterectomy was a leading reason for use of health insurance by women insured by SEWA, a women's organisation that operates a community-based health insurance scheme. Of insured women, 9.8% of rural women and 5.3% of urban women had had a hysterectomy, compared to 7.2% and 4.0%, respectively, of uninsured women. Approximately one-third of all hysterectomies were in women younger than 35 years of age. Rural women used the private sector more often for hysterectomy, while urban use was almost evenly split between the public and private sectors. SEWA's community health workers suggested that such young women underwent hysterectomies due to difficulties with menstruation and a range of gynaecological morbidities. The extent of these and of unnecessary hysterectomy, as well as providers' attitudes, require further investigation. We recommend the provision of information on hysterectomy as part of community health education for women, and better provision of basic gynaecological care as areas for advocacy and action by SEWA and the public health community in India.

Résumé

L'article présente les conclusions d'une enquête transversale sur la prévalence de l'hystérectomie auprès de femmes (2214 rurales et 1641 urbaines) assurées et non assurées dans des ménages à faible revenu de la ville et du district d'Ahmedabad à Gujarat, Inde. L'étude souhaitait déterminer pourquoi l'hystérectomie était une raison majeure de recours à l'assurance maladie de la part des femmes assurées chez SEWA, une organisation féminine qui gère un plan communautaire d'assurance maladie. Parmi les assurées, 9,8% des femmes rurales et 5,3% des femmes urbaines avaient subi une hystérectomie, contre 7,2% et 4,0% respectivement des femmes non assurées. Environ un tiers des hystérectomies avait été réalisées chez des femmes de moins de 35 ans. Les femmes rurales utilisaient plus souvent le secteur privé pour l'hystérectomie, alors qu'en ville, l'utilisation était répartie de manière égale entre les secteur public et privé. Les agents de santé communautaire de SEWA ont suggéré que ces jeunes femmes avaient subi une hystérectomie pour des troubles de la menstruation et différentes morbidités gynécologiques. Il convient de réaliser des recherches complémentaires sur l'étendue de ces interventions et des hystérectomies inutiles, ainsi que sur les attitudes des prestataires. Nous recommandons la diffusion d'informations sur l'hystérectomie dans le cadre de l'éducation sanitaire communautaire des femmes, et de meilleurs soins gynécologiques essentiels comme domaines de plaidoyer et d'action de SEWA et de la communauté de santé publique en Inde.

Resumen

En este artículo se presentan los hallazgos sobre la prevalencia de la histerectomía de una encuesta domiciliaria transversal, realizada en 2010, de 2214 mujeres rurales y 1641 urbanas aseguradas y no aseguradas, en viviendas de bajos ingresos en la ciudad y el distrito de Ahmedabad, en Gujarat, India. El estudio investigó por qué la histerectomía era una razón principal para el uso de seguro médico por mujeres aseguradas por SEWA, una organización de mujeres que administra un plan de seguro médico comunitario. De las mujeres aseguradas, el 9.8% de las mujeres rurales y el 5.3% de las urbanas habían tenido una histerectomía, comparado con el 7.2% y el 4.0%, respectivamente, de las mujeres no aseguradas. Aproximadamente una tercera parte de todas las histerectomías se efectuaron en mujeres menores de 35 años de edad. Las mujeres rurales acudieron al sector privado con más frecuencia para una histerectomía, mientras que las urbanas se dividieron casi exactamente por la mitad entre los sectores público y privado. Los trabajadores comunitarios de la salud empleados por SEWA sugirieron que estas jóvenes tuvieron histerectomías debido a sus dificultades con la menstruación y una variedad de morbilidades ginecológicas. La gravedad de éstas y la frecuencia de histerectomías innecesarias, así como las actitudes del personal de salud, requieren más investigación. Recomendamos el suministro de información sobre la histerectomía como parte de la educación de las mujeres comunitarias sobre la salud, y mejor prestación de los servicios ginecológicos básicos, como áreas de promoción y defensa y acción por parte de SEWA y la comunidad de salud pública en India.

The primary aim of this paper is to present information on the prevalence of hysterectomy, the main providers of hysterectomy services, associated out-of-pocket expenses and policy implications from a recent survey of women in low-income households in Ahmedabad district in the Indian state of Gujarat. Hysterectomy is the surgical removal of the uterus, a procedure that is typically conducted in the later phase of a woman's reproductive life for medical indications such as cervical or uterine cancer, fibroids, endometriosis or a prolapsed uterus. Ordinarily, hysterectomy is considered a second-line treatment, only after less invasive options such as removal of fibroids or hormonal treatment have been explored. The medium- and long-term side effects of hysterectomy can include the physical and emotional effects of hormone imbalance associated with menopause, loss of interest in sexual activity, and illnesses that result from an overall weakened body.Citation1 Moreover, hysterectomy can be associated with significant out-of-pocket expenses for households.

Research on hysterectomy in developing countries is limited. Most studies on the trends and drivers of hysterectomy relate to developed countries, through analysis of population surveillance, hospital records data and surveys. Available estimates from 2006 in Australia and 2008 in the United States indicate that about one in three women have had a hysterectomy by age 65.Citation2Citation3 Estimates for the United Kingdom from 1992 and Ireland from 2000 suggest a somewhat lower prevalence: 22% and 20%, respectively.Citation4Citation5 This research, while pointing to variation in prevalence across settings, indicates that hysterectomy is an area of concern and investigation.

In India, studies on hysterectomy until the last decade have focused primarily on clinical outcomes, with limited analysis of the prevalence of hysterectomy and its public health implications.Citation6–9In a 2008 study in Haryana, one of India's wealthier states, Singh and AroraCitation10 found that 70 women in a rural sample of 1,000 women had undergone a hysterectomy, primarily for heavy menstrual bleeding. The paper does not indicate whether non-invasive treatments were first offered. Over half of these cases were conducted in a private health care facility. Approximately half (46%) of women who underwent hysterectomy reported some form of later complication, e.g. bleeding, fever or pain. The authors concluded that the study area had a lower overall hysterectomy rate (7%) than developed countries due to poverty, illiteracy and fear of surgical operations. However, caution must be exercised in comparing rates in Indian women aged 15 and above to Western rates, as only one generation of women of reproductive age in India is likely to have had access to the procedure. In fact, when age-specific prevalence of ever having undergone hysterectomy is considered, the estimated prevalence in 2008 of 15.1% in women aged 45–54 years in Haryana is comparable to prevalence estimates for the United Kingdom in 1992.Citation4

Recent research in Andhra Pradesh suggests much higher rates of hysterectomy than in Haryana, and in relatively younger women. A 2010 study in a rural population found that 14.5% of 3,452 women of reproductive age surveyed had already undergone the procedure at a median age of 24 years (age range not provided).Citation11 The main conditions for which hysterectomy was indicated were acute pelvic inflammatory disease, uterine bleeding, prolapsed uterus and urinary tract infection. Almost all respondents had sought prior treatment for a gynaecological condition, after which hysterectomy was recommended in the second set of consultations. The study also found that the women perceived hysterectomy to be a desirable course of action either because they had achieved their intended family size, or wished to rid themselves of menstrual difficulties.Citation11 As in Haryana, a large majority of the respondents utilised private facilities for undergoing a hysterectomy. Although the age distribution of women with hysterectomy in the sample population was not provided, the data point to hysterectomies being carried out at younger ages than is usually medically indicated. Indeed, an analysis of hysterectomy cases among a different sample of women in rural areas of Andhra Pradesh concluded that hysterectomy was rarely medically indicated in women below age 45. Taken together, these findings raise ethical concerns that should be investigated further.Citation12

These findings are consistent with the findings of Ranson and John,Citation13 who studied 63 hysterectomy claims among a sample of insured, informal sector women workers in a rural district of Gujarat in 2001, among whom 53 (84%) had undergone hysterectomy at a private, for-profit hospital. In interviews, providers said they often carried out medically unnecessary hysterectomies due to women's insistence on having the procedure, although there was also some suggestion that some doctors were driven by a profit motive. This study also identified a lack of primary, non-invasive treatments for indicated gynaecological conditions, suggesting that hysterectomy may have served as first-line treatment.Citation13

Although reliance on private providers suggests that hysterectomies may impose significant out-of-pocket expenses for low-income households, no further evidence is available to date on this subject.

While existing studies provide basic background on hysterectomy in parts of India, more information is needed on prevalence, drivers and the economic impacts on women's households so as to help to regulate potentially unnecessary use of the procedure and inform health financing mechanisms. This paper presents results from a survey by the Self Employed Women's Association (SEWA) in a population of low-income women in Gujarat, India.

Study setting

Gujarat is among the fastest growing Indian states in terms of economic performance in the past decade. Improvements in its health indicators, however, are not as impressive. The infant mortality rate in Gujarat is estimated to be 50 per 1,000 live births, which is roughly equal to the national average. The maternal mortality ratio is slightly better, at 160 per 100,000 live births, lower than the national figure of 254 per 100,000 live births.Citation14 However, the sex ratio – an indication of both women's status and access to diagnostic technology – is 920 females per 1,000 males, compared to 933 for India as a whole.Citation15

Much as in the rest of India, the private sector accounts for a significant share of health services in Gujarat. This is also reflected in out-of-pocket household expenditure for health care, mostly in the private sector, that amounts to roughly 78% of all health spending in the state.Citation16 The reliance on private services is not surprising, given that the public health system faces a shortfall in human resources, particularly physicians and specialists. For example, there are seven obstetricians/gynaecologists officially employed in Gujarat's public health system, with 267 unfilled slots.Citation17 In addition to increasing investment in the public health system, the government of Gujarat has introduced a number of contractual arrangements with private sector health service providers, commonly referred to as public–private partnerships, to facilitate affordable access to health care. Services provided in this manner include institutional delivery, post-natal and newborn care and emergency ambulance services for any medical purpose.Citation17

This study is part of a larger action–research initiative on women's health being implemented by SEWA. SEWA is a trade union of over 1.6 million women workers across nine states of India, founded in 1972 in Gujarat. SEWA members tend to be involved in occupations requiring hard manual work with long hours and low pay. Being in the informal sector, they have limited access to formal social security benefits, and previous research has shown that ill-health is the leading cause of indebtedness amongst SEWA members.Citation18 As part of the union's services to women workers and their communities, SEWA implements a two-pronged community health programme. Firstly, SEWA's community health workers strengthen access to and utilisation of public health services for women, primarily through education and grassroots advocacy. Secondly, SEWA offers women and members of their households a voluntary, community-based health insurance scheme, called VimoSEWA, in return for a premium payment. By financing expenses (up to a certain limit) for hospitalisation of at least 24 hours in both public and private hospitals, VimoSEWA seeks to reduce financial barriers to health care for women workers and their families.

Methodology

A recent analysis of VimoSEWA's health insurance claims identified hysterectomy as a major reason for hospitalisation, along with fever and waterborne illnesses amongst adult women.Citation19 Surprised at these findings, particularly hospitalisation for illnesses that could ordinarily be treated through primary care, SEWA hypothesised that its community health worker team could provide health education to (i) reduce hospitalisation and expenditure for fever and water-borne illnesses and (ii) improve women's knowledge on hysterectomy, with the aim of reducing unnecessary surgery.

Accordingly, SEWA initiated a cluster randomised trial in 2010 to evaluate the impact of community health worker-led health education on health-seeking behaviour, hospitalisation and out-of- pocket expenditures among its members and their households. Twenty-eight discrete geographic clusters were identified in Ahmedabad district and Ahmedabad city, areas in which both SEWA community health workers and VimoSEWA are active. In 14 randomly selected intervention clusters, health workers will conduct group education sessions amongst women on primary illness and hysterectomy for a two-year period, while health workers in 14 control areas continue with their regular activities.

The survey sample included equal shares of households with SEWA health insurance and those without SEWA insurance, in order to assess the effect of health insurance on women's care-seeking behaviour. A total of 70 households were sampled in each of the 28 clusters. Thirty-five households with health insurance were randomly selected from VimoSEWA's membership database through computer-generated numbering within each cluster. An equal number of households from the uninsured population were selected in the same cluster in a two-step process. First, the research team listed all uninsured households in a cluster by following a community health worker on her rounds, so that no household was excluded, particularly as many slum settlements are not listed in government rosters. Next, 35 households were randomly selected through a computer-generated numbering process for each cluster. In total, 1,960 households in 28 clusters were sampled.

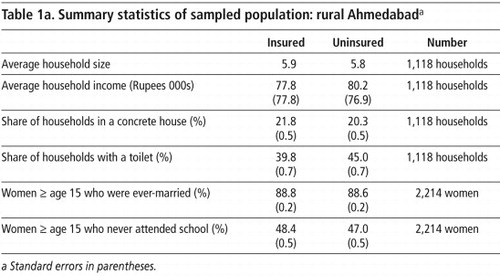

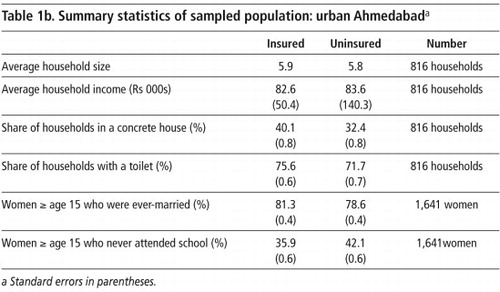

A baseline survey was conducted in January–March 2010 in 1,934 of the 1,960 households, which included 3,855 women over the age of 15. Information was collected on demographics, educational attainment and work status for each individual within a household, household income, preventive health practices and access to health services. Summary statistics for the sample population are reported in Table 1a

(rural) and Table 1b (urban). The survey asked the women about hospitalisation in the six months preceding the survey and outpatient treatment in the month preceding the survey, the sequence in which treatment and services were sought, health care expenditure and main sources of its financing.Among the rural women, the insured and uninsured populations were not significantly different on key characteristics. Among the urban women, there was also no difference in insured and uninsured populations, except that those living in a concrete home were slightly more likely to have health insurance (RR=1.21, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.39.) Throughout this paper, we present findings for insured and uninsured populations separately, as they were sampled differently and to identify any associations with health-seeking behaviour.

Prior to this study, SEWA had little information on the prevalence of hysterectomy, outside of what could be inferred from health insurance claims data – which naturally excludes women in the general, uninsured population. The survey collected information on hysterectomy in two ways. Cases of hysterectomy that required hospitalisation in the preceding six months were recorded at baseline, with detailed information on expenditure incurred and financing. New cases will be recorded over the next two years in a similar manner. The baseline survey also asked if any woman in the household had ever undergone a hysterectomy, at what age and the type of hospital where it was performed.

Findings on hysterectomy

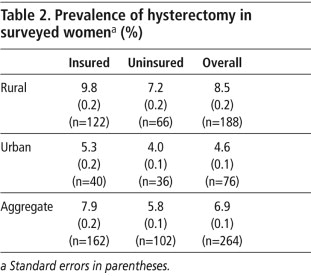

The findings from the baseline study indicate that approximately one in ten rural insured women over the age of 15 had had a hysterectomy, compared to 7% of uninsured rural women. In Ahmedabad city, about 5% of insured and 4% uninsured women had done so (Table 2

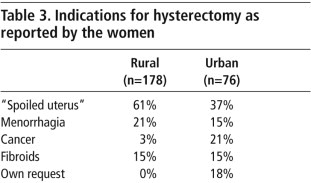

). Evidence is strong that prevalence of hysterectomy is higher in rural women, amongst both the insured and uninsured (p<.001). In Ahmedabad district, insured women were slightly more likely to have had a hysterectomy (RR=1.37, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.81, p<.05), while in Ahmedabad city the prevalence of hysterectomy was similar between insured and non-insured women.The medical indications most commonly reported by the rural women who underwent hysterectomy were “spoiled uterus”, followed by menorrhagia and fibroids (Table 3

). “Spoiled uterus”, according to an experienced local gynaecologist, is a lay term that refers to dysfunctional uterine bleeding (Patwa R. Personal communication, 3 March 2011). In the urban women, cancer – the specific type was not reported – accounted for a higher proportion of cases. The reasons reported for hysterectomy were similar across type of hospital and insurance status.Most of the conditions reported by rural women appeared to be benign, but lack of cancer detection services for low-income populations may have prevented accurate reporting of cancer, particularly cervical cancer, a leading cancer amongst women in rural India.Citation20Citation21

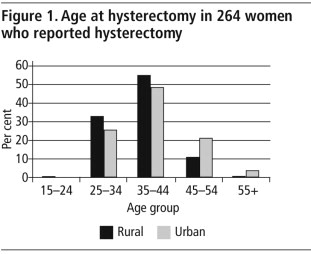

Rural women underwent hysterectomy at an average age of 36.6 years (range 23–55, SD 6.2) and urban women at 39.3 years (range 25–75, SD 8.5), with no difference based on insurance status. Notably, approximately one-third of all hysterectomies were in women younger than age 35 years (

).A comparison of the demographic characteristics (house type, education level and annual household expenditure) of women with hysterectomy and those without did not yield any obvious correlates. Annual household expenditure was relatively similar. Among insured rural women, those who had had a hysterectomy were more likely never to have been to school: 65.1% compared to 46.7% of those who did not have a hysterectomy (RR=2.29, 95% CI 1.43–3.66).

Health service utilisation and expenditure

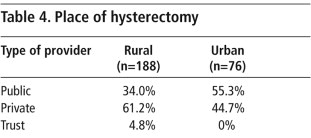

Rural women who had had hysterectomies used the private sector more than government services: close to two-thirds in a private hospital (Table 4

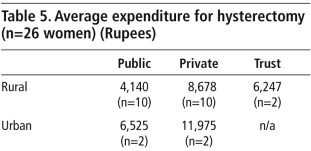

). This mirrors treatment-seeking behaviour more broadly in rural India, wherein the private sector accounts for the majority of care.Citation16 Among urban women, place of hysterectomy was almost evenly split between the public and private sectors. There was no association between insurance status and use of public vs. private hysterectomy provider.The survey also collected detailed information on expenditure incurred by the 26 women who had a hysterectomy in the previous six months. The average length of stay was five days, range 1–22 days. For both urban and rural women, the mean out-of-pocket expenditure in a private hospital was more than double that in a government institution (Table 5

). Consistent with national health expenditure trends for hospitalisation, the average expenditure for hysterectomy in urban areas was considerably higher than in rural areas. In India, although public health care is generally cheaper than in private institutions, it also involves out-of-pocket expenditure for room charges, medicines, tests and sometimes doctors' fees.Eight of the 26 women were able to pay using their own household resources, while the remainder borrowed from family, friends, moneylenders or other sources. Of those who borrowed, 15% were reimbursed by VimoSEWA for up to Rs. 2,000 of the total out-of-pocket expenditure incurred.

Community health workers' and providers' views

We presented these findings to a team of 14 SEWA community health workers who work with the populations from which our household sample came. Their reactions offer greater insight into our findings and point to areas for further investigation, particularly regarding women's own demand for hysterectomy. Most prominently, they felt that women's attitudes toward menstruation were a significant driver in seeking hysterectomy.

Menstruation is a taboo and a cumbersome process, and more so in rural India. Women cannot enter the kitchen, have restrictions on the work they can engage in and find washing and drying sanitary cloths in the open sunlight to be embarrassing. Sanitary napkins are not widely available or utilised. The view that removing the uterus will make the difficulties related to menstruation disappear “once and for all” is commonly expressed amongst women in health education sessions and in interaction with health workers. As menstrual taboos are generally more prevalent in rural areas, this may partially explain the higher rates of hysterectomy in Ahmedabad district.

Further, SEWA's community health workers hypothesised that rural women engaged in agriculture were more prone to uterine prolapse due to heavy lifting and agricultural labour. Thus, even though prolapse did not emerge in the survey as a primary reason for the surgery, it should be explored further, as well as whether other first-line treatment (such as fibroid removal or stitching for prolapse) are typically attempted before hysterectomy is prescribed, since insurance claims currently do not record this.

Another issue that emerged was whether hysterectomy is used as an alternative to sterilisation. The fact that free sterilisation is readily available in primary health care centres ought to obviate the need for an expensive hysterectomy for family planning. In fact, the government offers financial compensation to women who undergo sterilisation in the public sector.Citation22

Health workers also suggested that women who have already undergone sterilisation suffer from adverse effects and/or infections that may result in hysterectomy at a later stage. Some findings from Andhra Pradesh, as well as the United States, suggest that some types of tubal ligation may be associated with a later risk of menstrual disorders and/or hysterectomy, particularly in women sterilised at a young age.Citation11,23–26

In addition to these responses, in January 2010, four local gynaecologists were consulted by SEWA's health team while developing a film on hysterectomy to be used in intervention areas. The following quotations were video recorded:

“These women are poor and will not return for results or follow-up tests [after a Pap smear]; it is better to take care of problems permanently.” (Doctor 1)

“There is no other option – your women come to us too late and do not have knowledge of hygiene and sanitation.” (Doctor 2)

“Why not? Hysterectomy has few side effects and ensures she is no longer at risk for uterine cancer.” (Doctor 3)

“We don't do other procedures, as there is no risk after a woman has completed her family.” (Doctor 4)

Discussion

In the absence of a national or regional benchmark of what is considered appropriate for hysterectomy prevalence, it is difficult to know whether what we found was a low or high prevalence. However, the nature of the medical indications identified by the women and the age at which hysterectomy was done have public health significance, as does the financial burden on women.

The methodological strength of this study is that it allowed for an estimate of hysterectomy prevalence amongst insured and uninsured women in a rural and urban area of Gujarat. While the prevalence in uninsured rural (7.2%) and urban (4.0%) women may be extrapolated to urban centres such as Surat and its surrounding rural villages in the state, as well as similar areas across India, any wider extrapolation must consider that Ahmedabad is the largest city in Gujarat. Access to, and quality of, health facilities are on the whole likely to be better than in many parts of India, which may affect prevalence. By sampling uninsured and insured women separately, the study was designed to identify differences in health care utilisation, including hysterectomy, that may be associated with having health insurance. While health insurance at present covers only a small percentage of India's population, the government has recently introduced a national health insurance scheme for the poor, the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY). This study's findings, as discussed below, may have important implications for RSBY and India's health system.

Medical indications

Medical indications as reported here were based on women's reports, not clinical records. A review of VimoSEWA's health insurance claims did not provide further insight; the reasons cited by physicians in claim reports were similar to those of surveyed women. An epidemiological study of gynaecological morbidity is critical to understanding reasons for hysterectomy, while individual case review is required to determine if hysterectomy was medically necessary in each case, and if prevention or alternative treatments were possible.

Most of the conditions reported in the survey were amenable to non-invasive, less expensive treatment options – if women accessed care sufficiently early. For example, hormonal treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding, removal of abnormal cervical lesions if detected at an early stage, and stitching for prolapsed uterus. More research is required on (i) the availability of such treatment in public and private institutions (ii) provider knowledge and use of these (iii) if such procedures were indeed tried first, and most critically, (iv) the effectiveness of such first-line treatments in this population of women.

The average age at hysterectomy was certainly lower in this study (nearly one-third of 264 hysterectomies were in women less than 35 years of age) than that found in developed countries. This young age is cause for concern – no matter whether it indicates a high level of gynaecological morbidity or points to premature or unnecessary use of hysterectomy in treating gynaecological ailments.

Health system and providers

Ranson and John's qualitative research on quality of careCitation13 suggests that private providers may be more likely to prescribe a hysterectomy, rather than less expensive non-invasive procedures for gynaecological ailments. However, it may also be that providers simply do not have the equipment or ability to perform cauterisation for cervical lesions or advanced techniques for fibroid removal, which may explain why over 40% of rural cases and over 50% of urban cases of hysterectomy were carried out in public hospitals.

The implications for RSBY and health financing are important because hysterectomy emerged as the most common use for SEWA's health insurance amongst rural women in this study. Rates of hospitalisation, as indicated by a RSBY review in nine districts of India, are twice as high for women as for men.Citation27 Although detailed claims data are not yet available, it will be important to assess the level and pattern of hysterectomy claims. If hysterectomy emerges as a leading reason for RSBY claims, monitoring and ensuring appropriate use of hysterectomy will be a significant factor in the performance of RSBY.

Recommendations

Hysterectomy should be better integrated into ongoing women's health research. Areas for further investigation, based on insights from community health workers, include women's difficulties with menstruation such as heavy bleeding, gynaecological morbidity, social attitudes, and the possible association of hysterectomy and long-term effects of sterilisation. The extent of these and of unnecessary hysterectomy, as well as providers' attitudes, also require further investigation. While SEWA will conduct follow-up research on some of these issues in Gujarat, similar work in different regions of India will be important to understand national trends.

Also important will be ways to involve insurers such as VimoSEWA and the national health insurance scheme in monitoring hysterectomy, such as systematic claims review and detailed case documentation of medical history, particularly for younger women.

Our findings highlight the greatly under-developed state of care for gynaecological morbidity for low-income women in India, in both the public and private sector, which may be driving the use of hysterectomy for a range of gynaecological ailments. Further, in our experience, there is little information available for women on the adverse effects of hysterectomy, or on alternatives to it. We recommend the provision of information on hysterectomy as part of community health education for women, and better provision of basic gynaecological care as areas for advocacy and action by SEWA and the public health community in India.

SEWA is currently piloting a health education project on hysterectomy over a two-year period, the results of which will be shared with policymakers, practitioners and researchers nationally. Evaluations of interventions elsewhere in India would be highly desirable for understanding when and how they are most likely to be effective.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge valuable inputs provided by the SEWA Health team, research fieldwork conducted by the Indian Academy for Self-Employed Women and funding support from the International Labour Organization Microinsurance Innovation Fund.

References

- N Flory, F Bissonnette, Y Binik. Psychosocial effects of hysterectomy. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 59: 2005; 117–129.

- K Spilsbury, JB Semmens, I Hammond. Persistent high rates of hysterectomy in Western Australia: a population-based study of 83 000 procedures over 23 years. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 113(7): 2006; 804–809.

- Whiteman MK HS, Jamieson DJ, et al. Inpatient hysterectomy surveillance in the United States, 2000–2004. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2008;198(1):34.e1–7.

- MP Vessey, L Villard-Mackintosh, K McPherson. The epidemiology of hysterectomy: findings in a large cohort study. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 99(5): 1992; 402–407.

- S Ong, MB Codd, M Coughlan. Prevalence of hysterectomy in Ireland. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 69(3): 2000; 243–247.

- SP Puntambekar, A Patil, SN Joshi. Preservation of autonomic nerves in laparoscopic total radical hysterectomy. Journal of Laparoendoscopic and Advanced Surgical Techniques. 20(10): 2010; 813–819.

- KK Roy, M Goyal, S Singla. A prospective randomised study of total laparoscopic hysterectomy, laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy and non-descent vaginal hysterectomy for the treatment of benign diseases of the uterus. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 8: 2010; 8.

- S Shekhar, S Verma, R Motey. Hysterectomy for retained placenta with imminent uterine rupture in a preterm angular pregnancy. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 89(12): 2010; 1615–1616.

- R Sinha, M Sundaram, C Mahajan. Single-incision total laparoscopic hysterectomy. Journal of Minimal Access Surgery. 7(1): 2011; 78–82.

- A Singh, AK Arora. Why hysterectomy rate are lower in India. Indian Journal of Community Medicine. 33(3): 2008; 196–197.

- YR Padma. Hysterectomy: a neglected issue in reproductive health care, 2010. At: <www.sctimst.ac.in/amchss/Hysterectomy.pdf. >. Accessed 17 January 2011.

- S Kameswari, P Vinjamuri. Medical Ethics: A Case Study of Hysterectomy in Andhra Pradesh. 2009; National Institute of Nutrition: Hyderabad.

- MK Ranson, KR John. Quality of hysterectomy care in rural Gujarat: the role of community-based health insurance. Health Policy and Planning. 16(4): 2001; 395–403.

- Registrar General of India. Sample Registration System. 2008; RGI: New Delhi.

- Registrar General of India. Sample Registration System. 2004–5; RGI: New Delhi.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Report of the National Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. 2005; MOHFW: New Delhi.

- A Singh. Public private partnership: the way ahead. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2008. At: <http://mohfw.nic.in/NRHM/GOA%20Workshop/PDFs/02-05-08_pdf/Pre%20Lunch/Dr%20Amarjeet%20Singh.pdf. >. Accessed 3 March 2011.

- R Jhabvala, S Desai, J Dave. Social Income and Insecurity: Joining SEWA Makes a Difference. SEWA Academy Working Papers. 2010; SEWA Academy: Ahmedabad.

- S Desai. Keeping the “health” in health insurance. Economic and Political Weekly. 44(38): 2009; 18–21.

- MA Moore, Y Ariyaratne, F Badar. Cancer epidemiology in South Asia – past, present and future. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2: 2010; 49–66.

- A Nandakumar, T Ramnath, M Chaturvedi. The magnitude of cancer cervix in India. Indian Journal of Medical Research. 130(3): 2009; 219–221.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Standard Operation Procedures for Sterilization Services in Camps, 2008. At: <www.mohfw.nic.in/NRHM/FP/SOP_Book.pdf. >. Accessed 3 March 2011.

- GP Gentile, SC Kaufman, DW Helbig. Is there any evidence for a post-tubal sterilization syndrome?. Fertility and Sterility. 69(2): 1998; 179–186.

- IZ MacKenzie, W Thompson, F Roseman. A prospective cohort study of menstrual symptoms and morbidity over 15 years following laparoscopic Filshie clip sterilisation. Maturitas. 65(4): 2010; 372–377.

- LS Wilcox, B Martinez-Schnell, HB Peterson. Menstrual function after tubal sterilization. American Journal of Epidemiology. 135(12): 1992; 1368–1381.

- A SG Mall, BJ Van Voorhis. Previous tubal ligation is a risk factor for hysterectomy after rollerball endometrial ablation. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 100(4): 2002; 659–664.

- A Swarup. RSBY: the evolving scenario, 2011. At: <www.rsby.gov.in/Documents.aspx?ID=14. >. Accessed 3 March 2011.