Abstract

Pelvic organ prolapse is common in rural women in Nepal. Pregnancy in a woman with pelvic organ prolapse is uncommon and rarely continues beyond the second trimester. If it proceeds after that, the uterus usually ascends with progression of pregnancy and becomes abdominal, leaving little trace of prolapse. Pregnancy continuing to term with uterine prolapse is very rare. The case reported here is of a pregnant woman from a remote district in Nepal who had nine pregnancies and at 38 weeks of pregnancy presented at the district hospital with severe uterine prolapse, a large cervical ulcer and the baby's foot protruding from the cervix. Air transport was the only means of reaching the nearest hospital with emergency obstetric care, 200km away. The baby was delivered stillborn at the airport by the auxiliary nurse-midwife who accompanied her. Her husband was counselled for and had a vasectomy. The woman was fitted with a ring pessary but could not afford to go to the nearest town for surgery for the prolapse. People in remote areas of Nepal often seek medical advice very late. This and the lack of education, low utilisation of family planning services, and lack of skilled birth attendance and safe delivery centres at local level contribute to high maternal morbidity and mortality.

Résumé

Le prolapsus est fréquent chez les Népalaises rurales. La grossesse chez une femme avec prolapsus est inhabituelle et se poursuit rarement après le deuxième trimestre. Si elle continue au-delà, l'utérus s'élève avec la progression de la grossesse et devient abdominal, laissant peu de traces du prolapsus. Il est très rare qu'une grossesse arrive à terme en cas de prolapsus génital. Le cas décrit ici concerne une femme enceinte dans un district isolé qui a eu neuf grossesses et s'est présentée à 38 semaines à l'hôpital du district avec un prolapsus génital sévère, un large ulcère génital et le pied du bébé dépassant du col de l'utérus. Un transport aérien était le seul moyen d'atteindre l'hôpital le plus proche dispensant des soins obstétricaux d'urgence, à 200 kilomètres de là. La sage-femme infirmière auxiliaire qui accompagnait la mère a accouché le bébé mort-né à l'aéroport. Le mari a été vu en consultation et a subi une vasectomie. On a posé un pessaire à la femme, mais elle n'avait pas les moyens de se rendre à la ville la plus proche pour s'y faire opérer du prolapsus. Les habitants des zones isolées du Népal consultent souvent très tard les médecins. Ce phénomène ainsi que le manque d'instruction, le faible recours aux services de planification familiale, le manque d'assistance qualifiée à l'accouchement et l'absence de centres de maternité sans risque au niveau local contribuent à un taux élevé de morbidité et mortalité maternelles.

Resumen

En Nepal, el prolapso del órgano pélvico es común en mujeres rurales. El embarazo en una mujer con prolapso del órgano pélvico no es común y rara vez continúa más allá del segundo trimestre. Si continúa, el útero generalmente asciende con la evolución del embarazo y se vuelve abdominal, dejando poco rastro del prolapso. Muy rara vez el embarazo continúa a término cuando hay prolapso uterino. Aquí se presenta el caso de una mujer embarazada, de un distrito remoto, quien tuvo nueve embarazos y a las 38 semanas del embarazo acudió al hospital distrital con prolapso uterino severo, una úlcera cervical grande y el pie del bebé salido del cérvix. Transporte aéreo fue el único medio de llegar al hospital más cercano, a 200 km de distancia, para recibir cuidados obstétricos de emergencia. La enfermera auxiliar-partera profesional que la acompañaba la ayudó en un parto de mortinato en el aeropuerto. El esposo de la mujer tuvo una vasectomía tras recibir consejería al respecto. A la mujer le colocaron un pesario vaginal, pero ella no tenía los recursos financieros para ir al pueblo más cercano y someterse a una cirugía para el prolapso. Las personas en zonas remotas de Nepal a menudo buscan asesoría médica muy tarde. Esto aunado a la falta de educación, el uso infrecuente de servicios de planificación familiar y la falta de asistencia de parto calificada y centros de parto seguros a nivel local, contribuyen a las altas tasas de morbilidad y mortalidad maternas.

Pelvic organ prolapse is common in women in rural areas in Nepal.Citation1 Early marriage, early pregnancy,Citation2 unassisted home delivery, lack of health facilities, unwillingness to seek health care during pregnancy and childbirth due to various religious and social taboos, are the major contributory factors.Citation1 In addition, improper hygiene, unbalanced and non-nutritious diet and lack of proper rest during the puerperium make the condition worse.Citation1 Although the median age at marriage for women in Nepal is 18 years, uneducated women are often married by the age of 16.Citation3 Soon after marriage, they conceive, and most of them do not attend a health facility for regular antenatal care or delivery.Citation4Citation5

Pregnancy with uterine prolapse is rare.Citation6Citation7 Even if pregnancy occurs, the increase in the size of the developing fetus pushes the prolapsed uterus back into the abdominal cavity. While there have been a few reported cases of complete or partial uterovaginal prolapse in the second trimester of pregnancy,Citation8 it is rarely seen after the fourth month of gestation.Citation6 Fewer than 250 cases of pregnancy with uterine prolapse have been reported. Those reported were mostly up to the early third trimester.Citation7 I have found none which continued to full term reported in the literature.

While working as a medical officer in the Jumla district hospital in a rural area of Nepal, I attended a woman whose case is reported here, who presented at term pregnancy with uterovaginal prolapse in which the baby's foot was protruding, along with a huge pressure sore in the anterior lip of the cervix.

Situation at presentation

The woman was 36 years old, from a remote area in Jumla District. She came to the district hospital in November 2008 at 38 weeks of gestation in labour pain, which had started 28 hours back. Two hours after it commenced, her membranes ruptured. One leg of the baby then came out. They waited at home for 12 more hours. As labour did not progress further, she was carried to the district hospital; a distance of 14 hours walk. History revealed that she had not had regular antenatal check-ups. She had also not taken iron supplementation or had tetanus immunisation during pregnancy.

She was of moderate build and at arrival, her vitals were stable. Fetal heart beat was absent. Contractions were mild but regular. On inspection of the vagina there was a huge uterovaginal prolapse with decubitus ulcer on the cervix measuring 7×1 centimetres and a prolapsed foot (

).Obstetric history

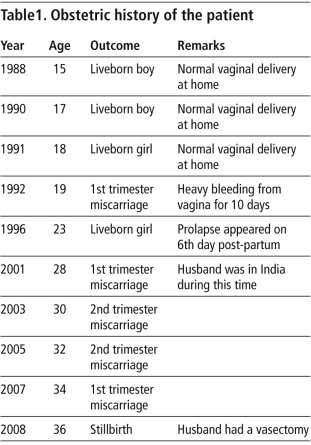

Married at 14 years of age, she was only 15 when she delivered her first child. She had had nine previous pregnancies, of which the first five resulted in four live births and one miscarriage (Table 1

). After the fifth pregnancy, a uterine prolapse appeared six days post-partum. Initially it was reducible but after three years it became irreducible. She became pregnant four more times with uterine prolapse before the pregnancy reported here, all of which ended in miscarriage in the first trimester or adverse fetal outcome, either stillbirth or neonatal death. She and her husband had not adopted any family planning method. Despite having these problems, she had never sought any medical help.Management

As it was late at night when she arrived, all laboratory facilities in the hospital were closed till the morning. We could not even find out her blood group. We continued with conservative management and supported her with intravenous fluids and antibiotics. We decided not to undertake any intervention at that point but to wait and refer her to the nearest centre with comprehensive obstetric care facilities – Bheri Zonal Hospital at Nepalgunj, which is about 200 km south of the district. The only means of transport there is by air, and for that too we had to wait, as the flights would only commence again in the morning.

Next morning, we sent her to the airport with an auxiliary nurse-midwife, who was asked to stay with her until she boarded the plane. In the interim, with the nurse-midwife's assistance, she delivered a stillborn baby of 3.2 kg in the airport while waiting to board the plane. She was brought back to the hospital and admitted for treatment of the decubitus ulcer.

She underwent dressing daily for 10 days and was discharged on the tenth day. She was treated with antibiotic, metronidazole and a combination of amoxicillin with clavulenic acid, in the hospital. Before discharge, her husband was counselled for sterilisation and vasectomy was performed.

Discussion

This is an extremely rare case. In her obstetric history, there were multiple pregnancies, complications of labour, lack of delivery by a skilled attendant, lack of adequate rest during the puerperium, and lack of nutritious food, all major contributing causes of uterine prolapse.Citation1Citation4Citation5Citation8 Had she had adequate rest, antenatal care and delivery at a health centre, maternal morbidity and mortality could have been reduced and the chance of a good fetal outcome increased.Citation7

Jumla is one of the most remote areas of Nepal and is lagging far behind in education and living standards compared to other districts. In Jumla, while 85% of pregnant women attend one antenatal visit, only 45% attend four times, as recommended by the World Health Organization. In addition, only 7.5% of births are attended by a skilled birth attendant.Citation9

Early marriage and early childbearing are the leading causes of uterine prolapse in our society.Citation3–6 Patriarchal norms pressure women to have male children, and go through repeated pregnancies to do so. This results in multiple pregnancies without sufficient child spacing.Citation10

I remained at the district hospital Jumla until April 2010. The woman had not received any further treatment for the uterine prolapse except for a ring pessary up to that time. Although I personally invited her to attend the district hospital during a uterine prolapse surgery camp, there were no such camps between November 2008 and March 2010. There is no record of whether she attended one after that. She could not afford to go to the nearest town for surgery for the prolapse.

People in remote areas of Nepal tend to seek medical advice at a very late stage, which is one of the leading reasons for higher morbidity and mortality. Lack of education, low utilisation of family planning services, and lack of skilled birth attendants and safe delivery centres at grassroots level have also contributed to this problem. A multisectoral approach by the Government and non-governmental organisations will be essential to ensure availability and use of safe delivery and family planning services.

References

- DK Sah, NR Doshi, CR Das. Vaginal hysterectomy for pelvic organ prolapse in Nepal. Kathmandu University Medical Journal. 8(2): 2010; 281–284.

- TR Bonetti, A Erpelding, LR Pathak. Listening to “felt needs”: investigating genital prolapse in Western Nepal. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(23): 2004; 166–175.

- MK Choe, S Thapa, V Mishra. Early marriage and early motherhood in Nepal. Biological Science. 37: 2005; 143–162.

- AM Fraser, JEB Rockert, RH Ward. Association of young maternal age with adverse reproductive outcomes. New England Journal of Medicine. 332(17): 1995; 1113–1117.

- SM Mawajedh, RJ Al-Qutob, AM Farag. Prevalence and risk factors of genital prolapse. Saudi Medical Journal. 24(2): 2003; 161–165.

- G Daskalakis, E Lymberopoulos, E Anastasakis. Uterine prolapse complicating pregnancy. Archives of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 276: 2007; 391–392.

- HL Brown. Cervical prolapse complicating pregnancy. National Medical Association. 89: 1997; 346–348.

- MS Piver, J Sepzia. Uterine prolapse during pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 32(6): 1968; 765–769.

- LB Rawal, SK Tiwari, BS Devkota. Women's educational status and maternal and child health care practices in Jumla district of West Nepal. Nepal Health Research Council. 2(2): 2004; 19–22.

- YB Karki. Sex preference and value of sons and daughters in Nepal. Studies in Family Planning. 19(3): 1988; 169–178.