Abstract

It is a continuing challenge to reach rural youth in India with sexual and reproductive health services. Drawing on a large survey among 6,572 young people aged 15–24 and 264 rural health providers accessed by them in rural West Bengal and Jharkhand, we witnessed a long-awaited response to national efforts to promote birth spacing. That 31% of young, married women without children were using contraception to delay a first birth was evidence of cracks in the persistent tradition of demonstrating fertility soon after marriage. The coverage of public sector services for reproductive and sexual health is highly variable and the scope largely restricted to married women, with unmarried young women and men relying mainly on the informal private sector, and seriously underserved. Strong social norms proscribing pre-marital sexual relationships perpetuate barriers in meeting their needs. Access to contraception is affected by negative provider attitudes and reluctance to report having sex underestimates the real scale of unmet need. Yet, 30% of providers reported unmarried young women seeking abortion services. To address the needs of all rural youth, the public sector needs to expand its remit or engage with informal providers, train them to deliver youth-friendly services and give them a recognised role in abortion referral.

Résumé

Atteindre les jeunes ruraux en Inde est un défi constantpour les services de santé génésique. Nous fondant sur une vaste enquête auprès de 6572 jeunes âgés de 15 à 24 ans et 264 prestataires de soins de santé ruraux auxquels ils avaient eu accès au Bengale occidental et à Jharkhand, nous avons constaté que les activités nationales de promotion de l'espacement des naissances avaient enfinobtenu des résultats. Le fait que 31% des jeunes femmes mariées sans enfants utilisent la contraception pour retarder la première naissance révèle une perte de terrain de la tradition consistant à prouver la fécondité rapidement après le mariage. La couverture du secteur public pour la santé génésique varie beaucoup et les services sont principalement réservés aux femmes mariées. Les jeunes célibataires comptent essentiellement sur le secteur privé informel et sont gravement sous-desservis. Les normes sociales rigides qui proscrivent les rapports sexuels avant le mariage continuent de contrarier la satisfaction des besoins. Les attitudes négatives des prestataires influencent l'accès à la contraception et l'échelle réelle des besoins insatisfaits est sous-estimée du fait de la réticence à avouer les rapports sexuels. Pourtant, 30% des prestataires ont indiqué que des jeunes femmes célibataires avaient demandé un avortement. Pour répondre aux besoins de tous les jeunes ruraux, le secteur public doit élargir ses attributions ou recruter des prestataires informels, les former à assurer des services adaptés aux jeunes et leur confier un rôle reconnu dans l'aiguillage des cas d'avortement.

Resumen

En India es un reto proporcionar servicios de salud sexual y reproductiva a la juventud rural. En una encuesta entre 6,572 jóvenes de 15 a 24 años y 264 profesionales de la salud que los atendieron en las zonas rurales de Bengal Occidental y Jharkhand, presenciamos una muy esperada respuesta a los esfuerzos nacionales por promover el espaciamiento de nacimientos. El hecho de que el 31% de las jóvenes casadas, sin hijos, estaban utilizando anticonceptivos para aplazar su primer parto, evidenció los problemas con la persistente tradición de demostrar la fertilidad poco después del matrimonio. Limitada principalmente a mujeres casadas, la cobertura de los servicios de salud sexual y reproductiva en el sector público es muy variable. Las jóvenes solteras y los hombres que dependen principalmente del sector privado informal son sumamente desatendidos. Las estrictas normas sociales que proscriben las relaciones prematrimoniales perpetúan las barreras para atender sus necesidades. El acceso a los anticonceptivos es afectado por las actitudes negativas del personal de salud y, debido a la renuencia a admitir que tienen relaciones sexuales, el cálculo de la verdadera escala de la necesidad insatisfecha es demasiado bajo. No obstante, el 30% del personal de salud informó que las jóvenes solteras buscan servicios de aborto. Para atender las necesidades de la juventud rural, el sector público debe ampliar su cometido o colaborar con prestadores de servicios informales, capacitarlos en la prestación de servicios amigables a la juventud y darles una función reconocida en la referencia a los servicios de aborto.

Youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services have gained increasing attention in India over the last decade. Delaying the age at marriage and first births are major programmatic goals to prevent a large burden of ill-health associated with early pregnancy and childbearing. Sexual initiation is largely within the context of marriage and most public health services for Indian youth have focused on young married couples. Sex before marriage is occurring, however, and with efforts to delay marriage, premarital conceptions will continue to rise. A sub-nationally representative study among youth in six Indian states in 2006–07 found that 12% of unmarried young men and 3% of unmarried young women reported pre-marital sex – with proportions slightly higher in rural populations, 14% and 4% respectively.Citation1 Since childbearing outside marriage is highly stigmatised, any unintended pregnancies resulting from conception before marriage will nearly always result in abortions.Citation2 While abortion has been legal for women in India under a wide range of conditions since 1971, and medical abortion pills available since 2002, access to these services remains a problem, especially for young and unmarried women.Citation3–5

The 2003 World Health Organization Reproductive Health Strategy called for new and innovative ways of improving service availability to adolescents and the poor, and those living in hard-to-reach areas. Within India, the 2000 National Population Policy, 2002 National AIDS Prevention and Control Policy, 2003 National Youth Policy, and the Reproductive and Child Health (RCH) Programmes I and II have all recognised the need to address the sexual and reproductive health needs of youth. Most recently, the national strategy for Adolescent Reproductive and Sexual Health approved under RCH II has been incorporated into the National Rural Health Mission in 2005. It emphasises inter-sectoral convergence and the creation of links with other vertical national programmes aimed at improving population health.Citation6 The Adolescent strategy focuses on reorganising existing public health services in order to meet the needs of adolescents. The auxiliary nurse-midwife is designated as the frontline worker (at the sub-centre level – one per 5,000 population). She enrolls newlywed couples, provides spacing methods and routine antenatal care, preventive education on sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV/AIDS and acts as a referral point for STI clinics, integrated counselling and testing centres and medical abortion services.Citation6

While adolescent-friendly services are available in theory to both married and unmarried adolescent boys and girls, there is an implicit (and sometimes explicit) focus on married adolescent mothers in order to achieve a reduction in infant and maternal mortality and increase birth spacing. This emphasis also excludes single adolescents and youth aged 20–24. As a result, some non-government organisations (NGOs) have begun designing youth-friendly services that strengthen the capacity of providers, whether in the formal or informal sectors, that are currently accessed by the full range of young people.

The public health infrastructure is stronger in rural West Bengal with 40% of villages having a government health facility (mainly sub-centres; only 5% have a Primary Health Centre), compared to Jharkhand where 30% of villages have a government health facility but only 1% of villages have a Primary Health Centre.Citation7 While the formal private sector is largely limited to urban areas, the informal private sector dominates rural areas with most providers practising modern allopathy without any formal medical qualification.Citation8 In West Bengal 82% of all non-hospital illness episodes were seen by these providers.Citation9 Their popularity is based on the fact that they are part of the community, working from unobtrusive set-ups where a person can walk in at any time and buy drugs on credit if needed.Citation8Citation9 In West Bengal there is a preference for public sector services when an abortion is needed, despite the greater trust in the informal providers to keep the matter confidential.Citation9

Antenatal care services in West Bengal are predominantly in the public sector. Ninety-six per cent of women get at least one antenatal check-upCitation7, with 80% of women accessing public sector services and 37% private sector (some went to both). In Jharkhand only 56% of women receive at least one antenatal check-up; more do so in the private sector (44%) than in the public sector (26%).Citation7

This paper draws on baseline data from two large intervention projects that seek to improve sexual and reproductive health services for both married and unmarried youth. The intervention strategies included training of formal and informal providers, awareness raising through community-based youth clubs, and advocacy work for rights-based approaches. Our aim was to assess what services young people were currently using and who provided them, and to explore whether availability of services depended on marital status.

Data and methods

Two contrasting settings were chosen for the interventions. The first was in South 24 Paragana district, West Bengal, a rural area relatively advantaged by its proximity to the state capital. In contrast, Hazaribag district, Jharkhand, was far from any large urban centre in a state that lags behind on many human development indicators and in access to health services, including maternity care and abortion services.Citation10Citation11 In terms of reproductive health indicators, contraceptive prevalence among young married women aged 15–24 was 54% in West Bengal versus 15% in Jharkhand, while unmet need for contraception was 15% and 33%, respectively.Citation12

Study participants included a representative sample of young people aged 15–24 in the intervention areas. A two-stage, stratified design firstly sampled villages using probability proportional to size, based on the 2001 census. In each of 227 selected villages, four separate household lists were used to randomly select respondents from among eligible married and unmarried young men and women.

A survey questionnaire was administered through face-to-face interviews between May and July 2008. Respondents were interviewed by same-sex fieldworkers in private settings to ensure confidentiality. Participation was voluntary and study participants could refuse to answer some or all the questions. Given the cultural sensitivity of abortion, questions on previous abortions were asked to married women only. Verbal consent was taken from all respondents and in case of minors (below age 18) parents/guardians also gave consent.

A total of 6,572 young people aged 15–24 were interviewed, of whom 2,342 were married women, 1,919 married men, 960 unmarried women and 1,351 unmarried men. They were asked at which facilities they had accessed sexual and reproductive health services or would do so. Field workers then interviewed two of the named providers in each sampled village. Interviews focused on the range of services provided and practitioners' attitudes on sexual and reproductive health services for young people. A total of 264 service providers were interviewed, but failure to sample providers in smaller villages, which occurred more frequently in Jharkhand, resulted in fewer providers there being interviewed (26% of all those interviewed).

We present data from bi- and multivariate analysis and report adjusted odds ratios (AOR) from logistic regression when important background characteristics were controlled for. While having large samples gave reliable estimates, they are representative of relatively small geographical areas where the intervention was implemented and cannot be considered as representative of Jharkhand and West-Bengal.

Findings

Use of services reported by young people

Reported sexual experience among unmarried youth was low with only 70 unmarried men (5%) and six unmarried women (1%) reporting ever having had sex. While for women this estimate does not differ from the National Family Health Survey-3 (NFHS-3) data, reported levels among the men were lower than the national average of 13%.Citation12 The Youth in India study, which included a representative sample of young people from Jharkhand, gave state-wide levels of sexual engagement as 14% among rural unmarried men and 10% among rural unmarried women.Citation13 Some of the differences may be because, in our sample, only 11% belonged to the scheduled tribes, whereas in the Youth Study, it was 25% and sex before marriage is more common in this population group.Citation1 Probably more important is that the reported estimates in the Youth Study were derived from anonymous self-reports, which confirmed that there had been a great deal of under-reporting by both young men and women in face-to-face interviews.Citation13

Of the unmarried young men engaging in premarital sex, 28% reported condom use; two of the four unmarried women who answered this question had used a condom at last sex. Condom use at last sex was reported by 10% of married men and 9% of married women. Use of some form of contraception at last sex was reported by 34% of married men and 45% of married women. These reports were internally consistent as men are mostly married to younger women, and contraceptive use increases with marital duration and need for spacing (and limiting) births.

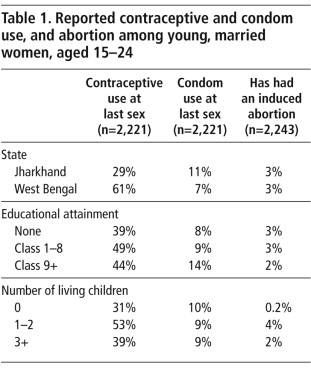

To compare use across several reproductive health services we restricted the analysis to married women. Table 1

presents reported levels of contraceptive and condom use, and induced abortion. Levels of contraceptive use among married women in West Bengal (61%) were higher than those reported in the 2005–06 NFHS-3 (54%), and nearly twice as high in Jharkhand (29%) vs. 15% in NFHS-3.Citation12We used logistic regression models to look at the independent effects of education, state and number of living children and controlling for the confounding effects of age and caste on these family planning practices. Women in West Bengal were more than three times more likely to report contraceptive use (AOR=3.33, p<0.001) than those in Jharkhand. In contrast in West Bengal women were significantly less likely to report condom use (AOR=0.41, p<0.001).

The likelihood of using contraception was highest for women with one or two children (AOR=1.95, p<0.001), suggesting that the main use was for spacing births. However, an unexpected finding was that 31% of childless women reported using contraception. In the 2006–07 Youth Study in Jharkhand only 5% of childless women reported using contraceptionCitation13 and in the last NFHS-3, overall 7% of childless women were using a method.Citation12 While we do not have details on the contraceptive method mix, we found that at least 10% of married women were using condoms to delay a first birth. Condoms become relatively less important for couples with children, with more or less constant levels at 9%, while overall contraceptive use was higher. Women with higher education (class 9 and above), were more than twice as likely to use condoms compared to those without education (AOR=2.28, p<0.001).

Less than 3% of the women reported having had an induced abortion, though this is likely to be under-reported. The pattern of abortion by number of living children demonstrates an increased motivation to space births, especially among those with smaller family sizes. Only one childless married woman reported an abortion, giving rise to a very large odds ratio for women with one to two children (AOR=20, p<0.01) and for women with three or more children (AOR=11, p<0.05). While more young couples seemed to take action to delay first births, it is much more unlikely that a childless married woman would terminate an unintended pregnancy.Citation2

Providing antenatal care is an important focus of the auxiliary nurse-midwife and the coverage showed large differences between the two settings. In West Bengal 99% of the married women reported at least one antenatal check-up for their most recent pregnancy, compared to 41% in the Jharkhand district. Antenatal care was statistically correlated with education, with the more educated women (class 9 and above) more than three times as likely to access antenatal care compared to those without education (AOR=3.19, p<0.001). Indeed, in settings where services are generally inaccessible, women's own ability to exercise informed choice critically influences levels of care received.Citation10 While not all antenatal care may have been delivered by government frontline workers, pregnant married women were the ones with most access to the public sector.

Services sought and available: reports of rural health providers

Two-thirds of providers currently accessed by the young people we interviewed had formal education up to Class 12, while about 30% had a Bachelor's degree or higher. Only 4% had a medical qualification, that is, were certified in any of the five medical systems (allopathy, homeopathy, unani, ayurveda or siddha). Only 6% of interviewed providers were women. A quarter held jobs in other sectors as well, including farming, manual labour, education and small business. Seven per cent of the providers interviewed were public sector, 3% formal private sector and 90% from the informal sector. The purposive sampling of providers clearly resulted in an under-representation of the public sector, in particular government frontline providers who, while mandated under the Adolescent strategy to deliver information and services, were clearly not yet recognised as doing this by the majority of young people.

Among the range of health conditions providers had been consulted on in the previous six months, menstruation issues, vaginal discharge and lower abdominal pain were the predominant ones on which both married and unmarried women consulted them. For men, semen discharge and nocturnal emissions (especially for unmarried men) were the most commonly reported concerns for which they sought care.Footnote*

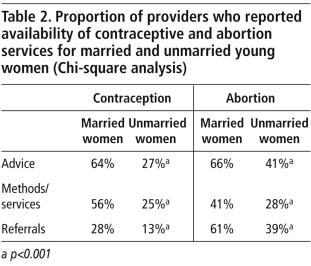

To assess availability of contraception and abortion services, providers were asked whether advice, treatment and referral services were available where they worked. Table 2

shows that the proportion of providers who said they offered contraception and abortion services to unmarried women was significantly lower than the proportion offering these to married women. However, providers showed less reluctance to provide advice, services or referrals for abortion once an unmarried young woman was pregnant. Nevertheless, withholding services from unmarried women that are available for the married ones clearly implies a negative attitude among providers.When asked for their opinion on delivering sexual and reproductive services to young people, only 31% of providers agreed with the statement: “All young people (married and unmarried) should receive information on contraception if they want it.” This sub-group of providers were more likely to have been contacted by unmarried women for contraception than the providers who disagreed with the statement (AOR=2.94, p=0.025).

The data on reported availability of services (Table 2) is consistent with what providers reported about specific consultations. About half of the providers reported they had been consulted on contraception by married men (48%) and women (53%) in the past six months. However, contraceptive services were also sought by unmarried men and women, with 16% of providers reporting consultations. The clearest evidence that sexually active unmarried youth do not get their contraceptive needs met was shown by the fact that 30% of providers reported consultations for abortion by unmarried women in the last 6 months.

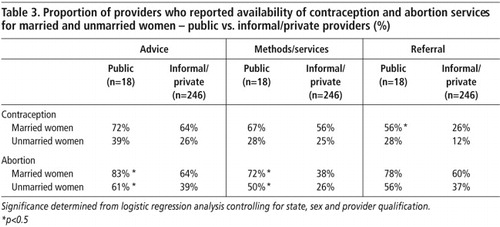

Although the 18 public sector providers were a small minority in our sample, they were more likely than the rest to report availability of contraception and abortion services; this was statistically significant for abortion (Table 3

). Thus, 72% of public providers versus 38% of private providers affirmed availability of abortion services for young married women at the facility where they worked (compared to 50% and 26% respectively for unmarried women). In addition, more public sector providers (56%) reported that at least one unmarried woman had consulted them for an abortion in the last six months, while only 29% of private providers had seen such a case.In a multivariate analysis, controlling for the effects of sex, state and provider's qualification, providers in the public sector were 15 times more likely to report abortion among married women in the previous six months than providers in the private sector. This was also the case for unmarried women, with public providers seven times more likely to report unmarried women seeking abortion.

Discussion

The trend of increasing contraceptive use among young people documented by comparing data from the National Family Health Surveys (NFHS-2 in 1998–99 and NFHS-3 in 2005–06)Citation12 is supported by our study. The 45% contraceptive prevalence among married women age 15–24 in this study is much higher than the national average of 28% reported in NFHS-3 which took place 2–3 years before our study. Direct comparison is difficult since our survey data are representative of relatively small geographical areas in two states and there are big differentials between different states in NFHS-3. The 61% in our sample in West Bengal and 29% in Jharkhand, however, indicate continued progress compared to the respective state-wide estimates of 54% and 15% in NFHS-3.Citation12

Our data are witness to a long-awaited response to national efforts to promote birth spacing methods and are consistent with a recent qualitative study in rural Madhya Pradesh that found growing autonomy among young couples in using contraception to space births, even when this conflicted with the view of their mothers-in-law.Citation17 We found that 31% of women without children were using some form of contraception and 10% were using condoms to delay a first birth. We know of no other study presenting quantitative evidence of cracks in the tradition of demonstrating fertility soon after marriage.

As most notable in relation to antenatal care, the coverage of public sector services was very variable. The 99% vs. 41% of ever-pregnant women reporting at least one antenatal check-up agrees with the District Level Household and Facility Survey showing 57% of villages in South 24 Paraganas district in West Bengal having a sub-centre with frontline workers,Citation18 versus only 24% of villages in Hazaribagh.Citation19 The public sector aside, even providers in the informal health care sector were harder to find in Jharkhand, as our failure to sample providers demonstrated.

Although the public sector, at least among our small sample, was doing better than the private sector in making contraceptive services available to unmarried young people the coverage and reach were still very poor. And despite the higher caseload for abortion among the public sector providers, we can infer that many young women with unwanted pregnancies would have had to go to informal providers. Indian abortion policy only allows physicians to provide abortion services; hence, access in rural areas, where very few providers are medically qualified, is particularly scarce.Citation3 Facility-based studies have shown that the unmarried and those from rural areas face considerable delay in obtaining abortion services and are thus more likely to undergo second trimester surgical procedures.Citation2Citation3Citation20 This should be addressed.

The need to broaden the cadre of providers who can legally provide abortion services remains pertinent.Citation21 A study on provision of medical abortion in 1,346 health facilities in Jharkhand and BiharCitation3 showed a high level of interest and willingness by mid-level providers to be trained for this.Footnote* Ideally, medical abortion pills could become more widely available through frontline nurse-midwives in the public sector, with referrals for both married and unmarried women from informal providers. Formalising referral links with informal providers is very important, as they have been shown to maintain good relationships with frontline workers and private clinics, should complications occur.Citation21

Our study underscores the central role informal providers continue to play in providing reproductive and sexual health care for rural young people. Generally, providers had negative attitudes towards providing services to those who are sexually active before marriage, but this was definitely more so among the informal providers, who were more likely to restrict contraceptive access based on marital status. The needs assessment we did prior to the baseline survey showed that health providers, on the whole, felt ill-equipped to address adolescent sexual and reproductive health issues. This highlights the importance of youth-friendly training for all providers, including values clarification. Unfortunately, government policy has been to exclude informal providers from training in delivering youth-friendly services in India. This is consistent with the continuing reluctance on the part of policymakers to formally recognise their important role in general health care provision because of the legal implications.Citation8

At the time of our survey, implementation of the Adolescent programme was only starting and outreach was very weak. However, by definition, this strategy excludes young people aged 20–24 and young adolescent men. Men have always been poorly served by the primary health sector,Citation16 and this is unlikely to improve by restricting services to adolescents.

A primary barrier in meeting the needs of the unmarried young continues to be the perpetuation of strong social norms proscribing pre-marital relationships. While Indian youth policy takes note of the needs of those who are sexually active and unmarried, the lack of explicit guidelines has led to shortfalls in programme implementation. Most young people do turn to the informal sector but there too they are met with negative attitudes. This is bound to make young people even more timid about approaching providers for contraceptive supplies.

The same strict norms have an impact on the reporting of sex before marriage in community-based surveys. Under-reporting has been shown to affect answers from both men and women,Citation13 and we certainly suspected this to be the case in our data. Ultimately this results in underplaying the extent of the barriers in access to these services. In addition, social norms influence the design of research and how findings are interpreted and inform the design of interventions. In our study, for example, questions on seeking abortion services were left out of the questionnaire for unmarried girls, in order to avoid offending the communities where the interventions were being planned. Although it is widely acknowledged that community-based surveys do not produce reliable estimates on abortion in any case,Citation2Citation5Citation20 by not even asking the question in an open and non-judgemental way the research itself reinforces these norms. Hence, we become complicit in perpetuating the denial of reality by not producing the evidence. Appropriate interventions are then not identified and young people suffer.Citation23

To end on a positive note we turn to condoms. Compared to the 5% of married women aged 15–24 reporting condom use in NFHS-3Citation12 we recorded 9% in our sample. Also, 28% of unmarried men in our study were using condoms at last sex – compared to 25% in the 2006–07 Youth Study.Citation1 While condom promotion is an explicit goal of the Adolescent strategy, users do not necessarily depend on public health services for supplies. Condom social marketing has been shown to be successful in reaching underserved men and unmarried women in sub-Saharan Africa, with a steady increase in condom use among the young, with pregnancy prevention often the main motive.Citation24 In both districts in our study, condoms were certainly widely available and affordable in rural markets, from local groceries, small utility shops and paan (beetle nut) shops. If indeed increases in contraceptive use indicate that young, married people have gained more agency to space births and more are now taking action to delay first births, long-standing norms may be transgressed to adopt protective behaviour. Provided sufficient information on sexual health and contraception reaches unmarried youth, and given that the condom supply is there, young people's agency to use condoms may hopefully change contraceptive behaviour, without first having to challenge social norms regarding pre-marital sex.

Conclusion

The challenges in addressing young people's reproductive and sexual health in India are enormous and depend on the development of an enabling social environment at all levels. The formal private sector is almost not visible in our study districts and is unlikely ever to serve large rural populations like these. Youth-friendly public services need to become far more accessible, but under current policy the public sector is likely to remain a source mainly of antenatal care and the means of birth spacing for young married women. Young, unmarried women and men who are not accessing public services currently rely mainly on informal providers and are often denied services even by them. For the Adolescent Reproductive and Sexual Health Strategy to succeed, increased resources are needed for reaching the rural poor, including young people aged 20–24. However, for the foreseeable future, the public sector will continue to find it difficult to meet all the reproductive and sexual health needs of the large population of young people in India, and informal providers will remain their most accessible source of advice. Frontline workers should take on outreach, counselling and provision of contraception to young people, married and unmarried, as well as the provision of abortion, including medical abortion. At the same time, however, it is essential that the public sector engages with the informal sector and gives them training in delivering youth-friendly services, and a recognised role in abortion referral.

Acknowledgements

The baseline data reported here come from two large-scale studies: Promoting Rights-based Action to Improve Youth & Adolescent Sexual & Reproductive Health including HIV/AIDS (PRAYASH) and Community Partnerships (CP): Modelling a Rights-Based Approach to Addressing Young People's Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights. These projects are implemented by Child in Need Institute (CINI) and supported by Interact Worldwide with funding from the European Union and Department for International Development. We are grateful to Lena Choudary Salter of Interact Worldwide for her input, encouragement and support.

Notes

* Many authors have discussed the issues of semen loss for men and abnormal vaginal discharge for women in India as being associated with feelings of weakness and indicating psychological distress rather than infection. Citation14Citation15 These concerns constitute a large case load seen by informal providers throughout India. Citation16

* Medical abortion pills are increasingly being accessed from pharmacies and drug sellers in many parts of India. Although in 2005, only 35% of chemists (the bigger outlets) in Bihar and Jharkhand were stocking medical abortion pills, Citation22 and use was not widespread, this may have changed substantially since then.

References

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) Population Council. Youth in India: Situation and Needs 2006–2007. 2009; IIPS: Mumbai.

- S Kalyanwala, AJF Zavier, S Jejeebhoy. Abortion experiences of unmarried young women in India: evidence from a facility-based study in Bihar and Jharkhand. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 36(2): 2010; 62–71.

- L Patel, TA Bennett, CT Halpern. Support for provision of early medical abortion by mid-level providers in Bihar and Jharkhand, India. Reproductive Health Matters. 17(33): 2009; 70–79.

- B Ganatra, S Hirve. Induced abortions among adolescent women in rural Maharashtra, India. Reproductive Health Matters. 10(19): 2002; 76–85.

- B Ganatra, S Kalyanwala, B Elul. Understanding women's experiences with medical abortion: in-depth interviews with women in two Indian clinics. Global Public Health. 5(4): 2010; 335–347.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. National Rural Health Mission: Meeting People's Health Needs, Framework for Implementation 2005–2012. 2005; MOHFW, Government of India: New Delhi.

- International Institute for Population Sciences. District-Level Household and Facility Survey (DLHS-3), 2007–08: India. 2010; IIPS: Mumbai.

- B Kanjilal, S Mondal, T Samanta. A parallel health care market: rural medical practitioners in West Bengal, India. Research brief. 2007; Indian Institute of Management: Jaipur.

- Bhat R. Private medical practitioners in rural India: implications for health policy. Report submitted to the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, 1999.

- SJ Jejeebhoy. Sexual and reproductive health among youth in Bihar and Jharkhand: an overview. Economic and Political Weekly. 1 December: 2007; 34–39.

- A Barua, H Apte. Quality of abortion care: perspectives of clients and providers in Jharkhand. Economic and Political Weekly. 1 December: 2007; 71–80.

- S Parasuraman, S Kishor, SK Singh. Profile of youth in India. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), India. 2005–06. 2009; International Institute for Population Sciences/ICF Macro: Mumbai/Calverton.

- International Institute for Population Sciences Population Council. Youth in India: situation and needs 2006–2007. Executive summary, Jharkhand. 2009; IIPS: Mumbai.

- A Bottéro. Consumption by semen loss in India and elsewhere. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 15(3): 1991; 303–320.

- V Patel, N Oomman. Mental health matters too: gynaecological symptoms and depression in South Asia. Reproductive Health Matters. 7(14): 1999; 30–38.

- M Collumbien, S Hawkes. Missing men's messages: does the reproductive health approach respond to men's sexual health needs?. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2(2): 2000; 135–150.

- A Char, M Saavala, T Kulmala. Influence of mothers-in-law on young couples' family planning decisions in rural India. Reproductive Health Matters. 18(35): 2010; 154–162.

- International Institute for Population Sciences. District-Level Household and Facility Survey (DLHS-3), 2007–08: India. West Bengal. 2010; IIPS: Mumbai.

- International Institute for Population Sciences. District Level Household and Facility Survey (DLHS-3), 2007–08: India. Jharkhand. 2010; IIPS: Mumbai.

- SJ Jejeebhoy, S Kalyanwala, AJF Zavier. Experience seeking abortion among unmarried young women in Bihar and Jharkhand, India: delays and disadvantages. Reproductive Health Matters. 18(35): 2010; 163–174.

- B Ganatra, L Visaria. Informal providers of abortion services: some exploratory case studies. 2004; Abortion Assessment Project – India: Mumbai.

- B Ganatra, V Manning, SP Pallipamulla. Availability of medical abortion pills and the role of chemists: a study from Bihar and Jharkhand, India. Reproductive Health Matters. 13(26): 2005; 65–74.

- L Visaria, V Ramachandran, B Ganatra. Abortion in India: emerging issues from qualitative studies. Economic and Political Weekly. 39(46–47): 2004; 5044–5052.

- J Cleland, MM Ali, I Shah. Trends in protective behaviour among single vs. married young women in sub-Saharan Africa: the big picture. Reproductive Health Matters. 14(28): 2006; 17–22.