Abstract

Timely access to emergency obstetric care is necessary to save the lives of women experiencing complications at delivery, and for newborn babies. Out-of-pocket costs are one of the critical factors hindering access to such services in low- and middle-income countries. This study measured out-of-pocket costs for caesarean section and neonatal care at an urban tertiary public hospital in Madagascar, assessed affordability in relation to household expenditure and investigated where families found the money to cover these costs. Data were collected for 103 women and 73 newborns at the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Mahajanga in the Boeny region of Madagascar between September 2007 and January 2008. Out-of-pocket costs for caesarean section were catastrophic for middle and lower socio-economic households, and treatment for neonatal complications also created a big financial burden, with geographical and other financial barriers further limiting access to hospital care. This study identified 12 possible cases where the mother required an emergency caesarean section and her newborn required emergency care, placing a double burden on the household. In an effort to make emergency obstetric and neonatal care affordable and available to all, including those living in rural areas and those of medium and lower socio-economic status, well-designed financial risk protection mechanisms and a strong commitment by the government to mobilise resources to finance the country's health system are necessary.

Résumé

Un accès ponctuel aux soins obstétricaux d'urgence est nécessaire pour sauver la vie des nouveau-nés et des femmes qui connaissent des complications à l'accouchement. Les frais à la charge des patientes sont l'un des facteurs critiques entravant l'accès à ces services dans les pays à revenu faible ou intermédiaire. Cette étude a mesuré le coût payé par les parturientes pour une césarienne et des soins néonatals dans un hôpital public urbain à Madagascar, a évalué s'il était abordable par rapport aux dépenses des ménages et a enquêté pour savoir où les familles avaient trouvé l'argent pour régler ces frais. Des données ont été recueillies pour 103 femmes et 73 nouveau-nés au Centre hospitalier universitaire de Mahajanga,dans la région de Boeny,de septembre 2007 à janvier 2008. Les frais occasionnés par une césarienne étaient catastrophiques pour les ménages de niveau socio-économique faible ou moyen, et le traitement des complications néonatales a aussi créé un lourd fardeau financier, des obstacles géographiques et d'autres contraintes financières limitant encore l'accès aux soins hospitaliers. L'étude a identifié 12 cas possibles où la mère avait exigé une césarienne et son nouveau-né des soins d'urgence, ce qui avait placé une double charge sur la famille. Afin de rendre les soins obstétricaux et néonatals abordables et disponibles pour tous, y compris les habitants des zones rurales et les ménages de niveau socio-économique moyen et faible, il faut disposer de mécanismes bien conçus de protection contre les risques financiers et compter sur la ferme volonté du Gouvernement de mobiliser des ressources qui financeront le système de santé du pays.

Resumen

El acceso oportuno a los cuidados obstétricos de emergencia es necesario para salvar la vida de mujeres que presentan complicaciones durante el parto y para recién nacidos. Los costos de las pacientes son uno de los factores críticos que obstaculizan el acceso a dichos servicios en países de bajos y medios ingresos. En este estudio se midieron los costos de las pacientes para una cesárea y atención neonatal en un hospital público urbano de tercer nivel en Madagascar, se evaluó la asequibilidad en relación con los gastos del hogar y se investigó dónde las familias encontraron el dinero para cubrir estos costos. Se recolectaron datos sobre 103 mujeres y 73 recién nacidos en el Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Mahajanga, en la región Boeny de Madagascar, entre septiembre de 2007 y enero de 2008. Los costos de las pacientes para cesáreas fueron catastróficos para familias de nivel socioeconómico medio-bajo, y el tratamiento de complicaciones neonatales también creó una enorme carga económica; las barreras geográficas y otras barreras financieras limitaron aun más el acceso a la atención hospitalaria. En este estudio se identificaron 12 casos posibles en los que la madre necesitaba una cesárea urgente y su recién nacido necesitaba cuidados de emergencia, doble carga para la familia. En un esfuerzo por poner los cuidados obstétricos de emergencia y la atención neonatal a precios asequibles a la disposición de las personas que viven en zonas rurales y aquéllas de nivel socioeconómico medio-bajo, se necesitan mecanismos bien diseñados para la protección de riesgos financieros y un sólido compromiso por parte del gobierno para movilizar los recursos necesarios para financiar el sistema de salud nacional.

Each year, the lives of half a million women and 1.5 million newborn babies are lost due to complications of delivery.Citation1 Timely access to emergency obstetric and newborn care in a medical facility is often necessary to save the lives of both women and newborn babies experiencing complications. Despite the fact that most maternal deaths are related to direct obstetric complications and carry a high risk of neonatal death, efforts to reduce pregnancy-related mortality have been less successful than those in other areas of human development. Caesarean section rates below 5% signal a lack of access to emergency obstetric care;Citation1 in rural sub-Saharan Africa, caesarean section rates are only about 2%.Citation2

The cost of emergency obstetric care, particularly caesarean section, is significantly higher than an uncomplicated delivery.Citation3–6 Financial barriers, both direct user fees and non-medical costs, such as transportation and accommodation, hinder access to emergency obstetric care, along with geographical distance, lack of knowledge and cultural barriers, and inadequate antenatal care within the formal health sector.Citation7–10 Out-of-pocket costs can negatively impact on access to maternal and infant health care, particularly at the hospital level,Citation8,11–13 and can impose a considerable financial burden on low-income households.Citation14Citation15 Catastrophic payments that make households unable to meet minimum needs, trigger the sale of productive assets and/or cause high levels of debt, leading to impoverishment,Citation16 are particularly common in low-income countries where health financing systems offer no protection from the financial burden of illness.Citation17

The consequences of paying for obstetric care can be long-lasting, with unexpectedly high costs challenging social expectations and patterns of reciprocity between husbands, wives and their wider social networks, placing enormous strain on everyday survival and shaping the physical, social and economic well-being of the family in the year following the event.Citation6

Life-threatening obstetric complications are unpredictable and often unpreventable. To prepare for this risk and make emergency care for women and infants affordable, sound financing mechanisms in health systems are needed, not only to ensure access to services, but also to prevent financial catastrophe by reducing out-of-pocket spending.Citation18 Various approaches to this have been taken in low- and middle-income countries, including the removal of user fees through government funding, various types of insurance, conditional cash transfers, voucher schemes and loan funds for transport costs.Citation7Citation13Citation19 While available evidence supports the removal of user fees and the provision of free delivery care to all women,Citation7Citation13 this may not be sufficient on its own. Other out-of-pocket costs, such as for transportation and unofficial provider payments, may remainCitation20–22 and skilled staff, equipment, supplies and support may not be available either.Citation4Citation22

Health care financing in Madagascar

Madagascar is a low-income country, with a per capita annual income of US$410 in 2008 and a population of 19.7 million, 73% of whom live in rural areas, where the poverty rate (74%) is higher than that in urban areas (52%).Citation23

After the economic crisis in 2001, the government of Madagascar suspended user fees at public health facilities. This included pharmaceutical charges, consultation fees and in-patient accommodation expenses for certain categories of patients at public health facilities. However, the increase in resources supplied by the government was not sufficient to compensate for the loss of user fees. Drug stock-outs became more common and the quality of services deteriorated as the workload of the already scarce health personnel increased.Citation24 At the end of 2003, the Government reinstated user fees, and by 2004, a new cost-recovery system was put in place at the health centre level. This system was accompanied by “equity funds”, an exemption mechanism to ensure that the poor had access to health care through the provision of free drugs from a community pharmacy. Although both government and non-governmental organisations have tried various types of protection measures for the poor, and risk-sharing schemes for health care at the hospital level,Citation25–27 at the time of our research, most surgical goods and other medical consumables had to be purchased prior to receiving hospital care, including emergency obstetric and neonatal care, resulting in high medical bills.

The health system in Madagascar suffers from low levels of financing. In 2007, the country spent US$41 per capita on health care, considerably lower than the average of US$67 for low-income countries.Citation28 Utilisation of formal health facilities is very low; only 10% of the population reporting an illness annually, of whom only 40% (i.e. 4% of all those seeking care at all) seek care from qualified medical personnel. Financial factors, including the direct cost of services, geographical distances, transportation and opportunity costs of seeking care, are a major barrier to health care access.Citation29 In 2007, only 58% of the population lived within 5km of a primary health centre.Citation24 Moreover, public health facilities suffered from a range of problems, including the inequitable distribution of human resources between urban and rural areas, and lack of essential goods and equipment to facilitate diagnosis and treatment, especially in rural and remote areas. In 2007, only 65% of public health centres had access to water, 31% electricity, and 56% any means of transport.Citation24

The maternal mortality ratio in Madagascar was estimated at 469 per 100,000 live births in 2000–2009 and the neonatal mortality rate 35 per 1,000 live births in 2008.Citation28 The caesarean section rate was about 1% of live births in 2000–2008.Citation28 It is well recognised that more intensified efforts are needed for the systematic improvement of referral services and comprehensive emergency obstetric care, for both pregnant women and newborns, particularly in rural areas.Citation30Citation31

In order to determine what is required to make these services more affordable and accessible, it is crucial to examine the magnitude of costs incurred by patients and their households and how they cope with these costs. This study focused on out-of-pocket costs for maternity services at a tertiary public hospital in Madagascar, with particular emphasis on emergency caesarean section and emergency neonatal care, and the affordability of these services according to socio-economic status.

Study site

The study took place in Boeny region, Mahajanga province, in the northwestern part of Madagascar, between September 2007 and January 2008. The region includes six health districts (Ambato-Boeny, Marovoay, Mahajanga I, Mahajanga II, Mitsinjo, Soalala) and has a population of about 543,200 people.Citation32

There are four hospitals in the region that should be providing caesarean sections: three are public hospitals and the fourth is missionary run. The Complexe Mère Enfant, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Mahajanga (CME/CHUM) is the main public hospital in the regional capital (Mahajanga I), an urban area with basic facilities and services, such as bank, post office, telephone, piped water and electricity, which are available to more people than in other districts. CME/CHUM has four specialists in obstetrics, gynaecology and paediatrics and provides tertiary care.

The missionary hospital is also located in the capital and also provides caesarean sections. However, patients of the missionary hospital mainly had private employment health insurance, which covers out-of-pocket expenses for direct hospital medical expenses.Citation33 The other two public hospitals are in Marovoay (2.5 hours' drive from the capital) and Soalala (9 hours' drive from the capital). Prior to the commencement of the study, the Boeny regional health office informed us that these two public hospitals only provided caesarean sections intermittently, due to staff shortages. In addition, the hospital in Marovay had introduced a pilot health care financing project which could impact on the out-of-pocket costs of caesarean sections and neonatal care. Considering these factors, we focused our study on patients at CME/CHUM, which had the staff and facilities to provide caesarean sections as required.

Methods

Questionnaires were administered during the study period to all women having caesarean sections at CME/CHUM and/or accompanying household members/relatives; and accompanying household members/relatives of all neonates admitted to the neonatal care unit and other units at CME/CHUM. The questionnaire covered household characteristics, patients' personal characteristics, and expenditure relating to hospital care. The same questionnaire was used for both caesarean sections and neonatal care.

An English version of the questionnaire was developed and translated into the local language (Malagasy). The Malagasy questionnaire was then back-translated in order to assure translation quality. The questionnaire was pilot-tested for ease of comprehension, clarity of definitions of cost items, and manageability of the length of the interview, and minor modifications were made.

Three locally trained interviewers visited maternity wards, neonatal care units and other wards daily for interviews after a two-day training session on data entry methods. Data were entered using EpiInfo and transferred to STATA for analysis.

McIntyre et al defined affordability as the degree of fit between the costs of using a service and the ability to pay in the context of the household budget and other demands on that budget. Ability to pay is the ability to obtain funds from the household or family, given all the demands placed on available funds. Affordability considers the potential impact on household well-being when using household resources.Citation34

Out-of-pocket costs were calculated as the sum of spending on hospital registration, specialist consultation, gifts or any informal payments to hospital staff, surgical operations, x-rays and laboratory tests, medicine purchased both outside and inside the hospital, food and accommodation for both patients and accompanying household members/relatives, transportation, and any other costs incurred during hospital stay. All costs were converted to US dollars using the average exchange rate during the study period (US$1=1,802 Madagascar Ariary).Citation35

Out-of-pocket expenditure was then compared for different socio-economic groups of the patients, utilising the following proxy indicators: Citation36Citation37 24 related to household ownership of consumer durables (car, mat, mobile phone, refrigerator, and television) and 19 related to household dwelling (main source of drinking water, main source of lighting and toilet facilities). The socio-economic status of each patient's household was calculated using these indicators and based on data from the Enquête Périodique auprès des Ménages (Periodic Household Survey or EPM) undertaken by the National Statistics Institute in 2005, using principal component analysis (details available from the first author).

The mean out-of-pocket expenditure incurred by women and their families was then compared to the mean annual household non-food expenditure in the Mahajanga province, as extracted from the EPM 2005. This was based on the principle that health care costs should not require households to reduce spending on basic subsistence. Given that poorer households devote a higher share of total income to food than less poor households, non-food household expenditure, rather than total household expenditure, better reflects the household's ability to pay for health care.Citation17

Strategies for finding the money to meet out-of-pocket expenditure were pre-coded and grouped into the following: use of routine wage or salary income, use of household savings, use of private employment health insurance, pawning of valuables, sale of household assets, financial assistance in the form of a gift of money, changing treatment, borrowing cash, reducing spending on other household items, and other.Citation16Citation38Citation39

Findings

The survey included a total of 103 women who had a caesarean section and 73 newborn babies (51 of them male) who required emergency neonatal care. The average age of the women was 26.4 years and of the babies 4.5 days (at the time of first interview).

Patient records for mothers and newborn babies were held in different sections of the hospital and there were no direct links between these records. Interview time was limited, particularly for women who had severe complications. Questions needed to be very clear – not confusing respondents about whether information related to the mother or the baby. Hence, data collected about the women and their babies could not be linked. However, by correlating the biographical data of the respondents, dates of their admission and discharge, and diagnoses, approximately 12 cases were identified where the mother had a caesarean section and her newborn baby received emergency neonatal care.

The main reasons for women needing caesarean sections included fetal distress (15.9%), failure to progress in labour (11.5%) and repeat caesarean (6.4%). For babies receiving neonatal care, the major diagnoses included acute fetal suffering (16.5%), premature birth (15.5%), jaundice (8.7%) and suspicion of neonatal infection (8.7%). The mean length of hospital admission was 6.9 days for women and 6.3 days for babies.

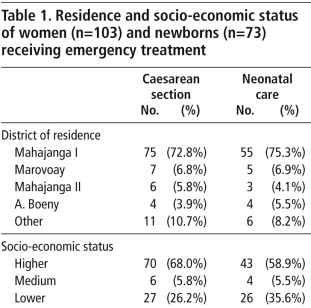

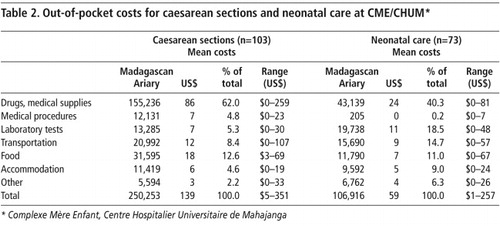

presents the demographic and socio-economic characteristics of respondents. The vast majority of patients (72.8% of women and 75.3% of newborn babies) came from the Mahajanga I district, where the hospital is located. About 68.0% of the women and 58.9% of the newborn babies belonged to the higher socio-economic groups.Mean out-of-pocket expenditure for caesarean section at CME/CHUM was estimated to be US$139 (Table 2

). Expenses for drugs and medical supplies accounted for the largest proportion of total costs (62.0%), followed by payment for food (12.6%).Mean out-of-pocket expenses for neonatal care at CME/CHUM were estimated to be US$59 (Table 2). Medical expenses accounted for the largest proportion of total costs, particularly for drugs and medical supplies (40.3%) and laboratory tests (18.5%). For non-medical costs, transportation accounted for 14.7% of total costs.

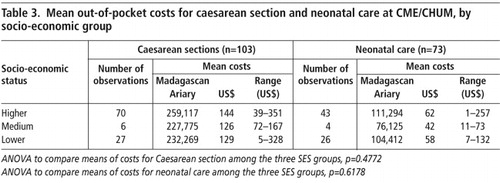

Mean out-of-pocket costs for caesarean sections were US$144 for the higher socio-economic group, US$126 for the medium socio-economic group and US$129 for the lower socio-economic group. Mean out-of-pocket expenses for neonatal care were US$62 for the higher socio-economic group, US$42 for the medium socio-economic group and US$58 for the lower socio-economic group. For both caesarean sections and neonatal care, no significant difference was found in out-of-pocket payments by socio-economic group (Table 3

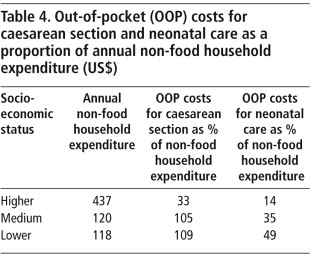

). The sample sizes for the medium socio-economic groups (both for caesarean sections and neonatal care) were small, which may have limited the statistical power in the analysis.Out-of-pocket costs for caesarean section as a proportion of annual non-food household expenditure ranged between 32.9% for the higher socio-economic group, 105.3% for the medium socio-economic group and 109.1% for the lower socio-economic group. The out-of-pocket costs for neonatal care as a proportion of annual non-food household expenditure was 14.1% for the higher socio-economic group, 35.2% for the medium socio-economic group and 49.0% for the lower socio-economic group (Table 4

).As the majority of patients (72.8% of women and 75.3% of newborn babies) came from the Mahajanga I district, where the hospital is located (Table 1), further analysis was undertaken on transportation expenditure according to district of residence. A significant difference was found in the transportation costs to the hospital between residents of Mahajanga I and those of other districts. Those from other districts paid more than twice the transportation costs as local residents (p<0.000).

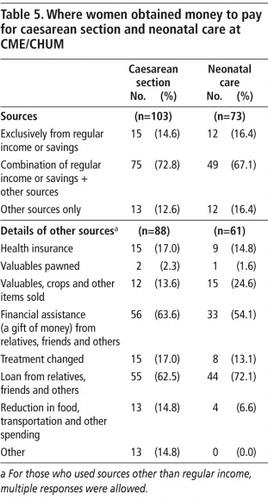

shows the methods used by the families of the women and neonates to obtain funds to pay for caesarean section and neonatal care. Only 14.6% of the women paid exclusively from routine income or savings; the remainder used various methods to obtain funds for the assisted delivery. Receiving financial assistance from relatives, friends and others in the form of a gift of money and borrowing cash from relatives, friends and others were the methods most commonly used.Only 16.4% of the families of neonates paid costs exclusively from routine income or savings. Borrowing cash and receiving financial help in the form of a gift of money from various sources were the other methods most commonly used to obtain funds (Table 5).

Discussion

Out-of-pocket costs for both caesarean section and neonatal care as a proportion of non-food household expenditure exceeded 40% for the lower socio-economic groups in this study. The mean out-of-pocket expenses for a caesarean section were estimated to be US$139 and for neonatal care US$59. Medical expenses, mainly drugs and medical supplies, accounted for the largest proportion of total costs both for caesarean section and neonatal care. For non-medical costs, payments for food and transportation during hospitalisation accounted for 21.0% of out-of-pocket payments for women and 25.7% for neonates. The minimum cost for many items was nil (Table 2) because some charity/missionary organisations provided assistance to the poor to cover hospital fees; those who were covered by private health insurance did not pay out-of-pocket for direct medical expenses at the hospital; and some came to the hospital on foot.

The out-of-pocket expenses for caesarean section were within the range of results from other studies in low- and middle-income countries. The household costs of caesarean section or other obstetric complications in lower-income countries have ranged between US$10 and US$385 in Benin, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania, Bangladesh and Nepal.Citation4Citation6Citation7 Only a small number of studies have estimated the out-of-pocket expenditure for neonatal care in low- and middle-income countries, making the potential for comparison limited.Citation40

We found no significant difference in the out-of-pocket payments for caesarean section and neonatal care between socio-economic groups. The share of annual non-food household expenditures spent on caesarean sections and neonatal care was higher among poorer than richer groups. This means lower-income households have a greater financial burden when requiring a caesarean and/or neonatal care. Interviewers reported that patients were not permitted to return home until they had settled their accounts for services received in hospital. This caused delays in discharge for those struggling to pay who consequently incurred additional accommodation and other expenses.

The out-of-pocket expenses for a caesarean section as a proportion of annual non-food household expenditure ranged between 32.9% for the higher socio-economic group, 105.3% for the medium socio-economic group and 109.1% for the lower socio-economic group, whereas the out-of-pocket costs for neonatal care were 14.1% for the higher socio-economic group, 35.2% for the medium socio-economic group and 49.0% for the lower socio-economic group. Thus, out-of-pocket expenses for a caesarean section exceeded the ability of medium and low socio-economic households to pay.

Some studies assume that a cost burden greater than 10% of household income or consumption expenditure is likely to be catastrophic for household economy.Citation41Citation42 Xu et alCitation17 present a new reference point by considering costs exceeding 40% of non-food household expenditure as being catastrophic for the household. On this basis, caesarean section would incur catastrophic costs for medium and lower socio-economic groups in this study, while expenses associated with emergency neonatal care represent a substantial proportion of non-food household expenditure for the lower socio-economic group.

Neonatal morbidity and mortality is linked to obstetric complications and maternal survival. Where both mother and infant receive emergency care, the out-of-pocket payments for treatment place a double burden on the household. Our study identified 12 possible cases where this happened, though our analysis is limited by methodological constraints to examine the linkage more explicitly. Given the call to improve health care across the continuum from pregnancy to newborn care,Citation1 in the absence of financial risk protection, cost implications for households where both emergency obstetric and neonatal care are required can be very heavy, particularly for lower socio-economic households.

Only about one in six households paid the costs incurred during hospital admission for women and newborns exclusively from routine income or savings. Most needed to use other methods, most commonly borrowing from family and friends. An important constraint is inability to access funds at the time of need, especially in rural areas, where subsistence farming is characterised by temporal or seasonal inability to pay.Citation7Citation43Citation44 Time spent looking for money can delay the decision to seek care and reduce timely access to care, with serious implications for maternal and neonatal outcomes.Citation7Citation45 We did not measure whether treatment was delayed due to payment considerations. However, one of the authors [MM] undertook a number of operational surveys during project work in 2006 and measured the time from admission to intervention in same hospital for 16 placenta praevia or abruption placenta patients who required immediate medical action for haemorrhage and fetal distress. The average time was around five hours. The delay in receiving medical treatment was usually because patients and their families had to find the money to purchase the necessary consumables and medicine needed following diagnosis and prior to surgery.

Of those treated in the hospital, 72.8% of the women and 75.3% of the newborns came from Mahajanga I, the regional capital where the hospital is located. Similarly, although 73% of the population in Madagascar live in rural areas,Citation23 only about 25% of the women and neonates admitted during the study period lived rurally, outside the district. Many women may have been unable to afford transport to the hospital from outside the district, and we may have underestimated the costs of transportation from further away. In addition, 68.0% of the women and 58.9% of the newborn babies in the study belong to the higher socio-economic group. Given the fact that 68.7% of the population in Madagascar live below the poverty line,Citation29 poorer women and families of newborn babies may not even have attempted to access the hospital.

The dearth of health facilities (only one of the three existing public hospitals) providing comprehensive emergency obstetric care for women in medium and lower income groups in the region and their location suggests that emergency obstetric and neonatal care may also have been geographically as well as financially inaccessible for rural women and babies.Citation34

Our findings support recent moves towards providing free emergency obstetric and newborn care at the point of delivery in order to reduce out-of-pocket costs and make these services more affordable. Madagascar's recent experience of establishing equity funds at the health centre level showed that identification of lower socio-economic households, in order to target the equity funds to those in need, was extremely difficult. The exemption scheme suffered from under-coverage and failed to protect the majority of the poor due to problems in policy design and implementation.Citation46 Consequently, the replacement of user fees with government funding (including donor funding) can be a more appropriate health care financing option for the country.

Any health care financing scheme needs to be carefully designed and develop implementation strategies that take account of effective referral and geographic, transport and socio-economic disparities relating to access. Removing financial barriers is imperative, especially in a country like Madagascar. However, considering the fact that the health system suffers from a lack of facilities, inequitable distribution of scarce human resources, a shortage of essential goods and equipment and inadequate levels of access to basic facilities, addressing issues relating to demand-side affordability alone will not be sufficient to ensure women and newborns can receive emergency obstetric and neonatal care. When the services become more affordable, the demand for them is likely to increase. It is imperative to concurrently address supply-side issues and undertake capacity building of staff and facilities and supply of medicines, to meet increased demand.

This requires a strong commitment from the Government, which needs to consider mobilising resources using tax measures and/or external sources to finance the country's health system and ultimately reduce maternal and newborn mortality.

Acknowledgements

The study was part of the Projet d'Amélioration du Service de Santé Maternelle, Néonatale et Infantile, funded by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), which aims to support mother and infant health in the Boeny region of Madagascar by helping to improve service provision and increase access to core health services. The authors are indebted to Prof Diane McIntyre and Mr Tiaray Razafimanantena for comments on the draft paper. Also, we are grateful to Dr Kara Hanson who provided advice during preparation of the study.

References

- WHO, UNICEF. Countdown to 2015 decade report (2000–2010): taking stock of maternal, newborn and child survival. 2010.

- UNICEF. Progress for children: a report card on maternal mortality. No. 7. 2008; UNICEF: New York.

- J Borghi, K Hanson, CA Acquah. Costs of near-miss obstetric complications for women and their families in Benin and Ghana. Health Policy and Planning. 18(4): 2003; 383–390.

- M Perkins, E Brazier, E Themmen. Out-of-pocket costs for facility-based maternity care in three African countries. Health Policy and Planning. 24(4): 2009; 289–300.

- Z Quayyum, M Nadjib, T Ensor. Expenditure on obstetric care and the protective effect of insurance on the poor: lessons from two Indonesian districts. Health Policy and Planning. 25(3): 2010; 237–247.

- KT Storeng, RF Baggaley, R Ganaba. Paying the price: the cost and consequences of emergency obstetric care in Burkina Faso. Social Science & Medicine. 66(3): 2008; 545–557.

- J Borghi, T Ensor, A Somanathan. Mobilising financial resources for maternal health. Lancet. 368(9545): 2006; 1457–1465.

- T Ensor, S Cooper. Overcoming barriers to health service access: influencing the demand side. Health Policy and Planning. 19(2): 2004; 69–79.

- AJ Gage. Barriers to the utilization of maternal health care in rural Mali. Social Science & Medicine. 65(8): 2007; 1666–1682.

- R Knippenberg, JE Lawn, GL Darmstadt. Systematic scaling up of neonatal care in countries. Lancet. 365(9464): 2005; 1087–1098.

- K Afsana. The tremendous cost of seeking hospital obstetric care in Bangladesh. Reprod Health Matters. 12(24): 2004; 171–180.

- J Borghi, T Ensor, BD Neupane. Financial implications of skilled attendance at delivery in Nepal. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 11(2): 2006; 228–237. (10).

- T Ensor, J Ronoh. Effective financing of maternal health services: a review of the literature. Health Policy. 75(1): 2005; 49–58.

- D McIntyre, M Thiede, G Dahlgren. What are the economic consequences for households of illness and of paying for health care in low- and middle-income country contexts?. Social Science & Medicine. 62(4): 2006; 858–865.

- A Wagstaff, Ev Doorslaer. Catastrophe and impoverishment in paying for health care: with applications to Vietnam 1993–1998. Health Economics. 12(11): 2003; 921–933.

- S Russell. The economic burden of illness for households in developing countries: a review of studies focusing on malaria, tuberculosis, and human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 71(2 Suppl): 2004; 147–155.

- K Xu, DB Evans, K Kawabata. Household catastrophic health expenditure: a multicountry analysis. Lancet. 362(9378): 2003; 111–117.

- K Xu, D Evans, G Carrin. Designing health financing systems to reduce catastrophic health expenditures, in Technical Brief for Policy Makers WHO/EIP/HSF/PB/05.02. 2005; WHO: Geneva.

- S Witter, DK Arhinful, A Kusi. The experience of Ghana in implementing a user fee exemption policy to provide free delivery care. Reproductive Health Matters. 15(30): 2007; 61–71.

- A Khan, S Zaman. Costs of vaginal delivery and Caesarean section at a tertiary level public hospital in Islamabad, Pakistan. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 10(1): 2010; 2.

- M Kruk, G Mbaruku, P Rockers. User fee exemptions are not enough: out-of-pocket payments for ‘free’ delivery services in rural Tanzania. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 13(12): 2008; 1442–1451.

- S Witter, T Dieng, D Mbengue. The national free delivery and caesarean policy in Senegal: evaluating process and outcomes. Health Policy and Planning. 25(5): 2010; 384–392.

- World Bank. Madagascar country brief. 2008 [cited 2010 16 June], Available from: http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/COUNTRIES/AFRICAEXT/MADAGASCAREXTN/0,,menuPK:356362˜pagePK:141132˜piPK:141107˜theSitePK:356352,00.html

- World Bank. Madagascar joint health sector support project, in Project Appraisal Document. 2009; World Bank: Washington DC.

- A Honda. User fees policy and equitable access to health care services in low- and middle-income countries - with the case of Madagascar. 2006; Institute for International Cooperation, Japan International Cooperation Agency: Tokyo.

- Minten B, Over M, Razakamanantsoa M, et al. The potential of community based insurance towards health finance in Madagascar. 2004.

- Noirhomme M, Criel B, Meessen B. Feuille de route pour le développement de Fonds d'Equité Hospitaliers à Madagascar: Ministère de la Santé et du Planning Familial, Banque Mondiale Madagascar. 2005.

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics. 2010; WHO: Geneva.

- INSTAT. Enquête périodique auprès des ménages 2005. 2007; Institut National de la Statistique: Antananarivo.

- Republic of Madagascar. Madagascar action plan 2007–2012: A bold and exciting plan for rapid development. Antananarivo. 2006.

- World Bank. Country assistance strategy for the republic of Madagascar for FY 2007–2011. 2007; World Bank: Washington DC.

- Ralison E, Goossens F. Madagascar: Profil des marchés pour les évaluations d'urgence de la sécurité alimentaire: Programme Alimentaire Mondial, Service de l'Evaluation des besoins d'urgence (ODAN). 2006.

- DRSPF Boeny Region, JICA. Projet d'amélioration du service de santé maternelle, néonatale et infantile, in Report on baseline survery. 2008; Directions Régionales de la Santé et du Planning Familial (Regional Health Office), Japan International Cooperation Agency: Majunga.

- D McIntyre, M Thiede, S Birch. Access as a policy-relevant concept in low- and middle-income countries. Health Economics, Policy and Law. 4(Pt 2): 2009; 179–193.

- Central Bank of Madagascar. Cours des devises mensuels en ariary. [cited 2011 04 March], Available from: http://www.banque-centrale.mg/

- D Filmer, LH Pritchett. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data–or tears: an application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography. 38(1): 2001; 115–132.

- S Vyas, L Kumaranayake. Constructing socio-economic status indices: how to use principal components analysis. Health Policy and Planning. 21(6): 2006; 459–468.

- A Leive, K Xu. Coping with out-of-pocket health payments: empirical evidence from 15 African countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 86(11): 2008; 849–856.

- R Sauerborn, A Adams, M Hien. Household strategies to cope with the economic costs of illness. Social Science & Medicine. 43(3): 1996; 291–301.

- OO Tongo, AE Orimadegun, SO Ajayi. The economic burden of preterm/very low birth weight care in Nigeria. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics. 2008. fmn107.

- N Prescott, M Pradhan. Coping with catastrophic health shocks, in Conference on poverty and social protection. 1999; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC.

- MK Ranson. Reduction of catastrophic health care expenditures by a community-based health insurance scheme in Gujarat, India: current experiences and challenges. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 80(8): 2002; 613–621.

- S Nahar, A Costello. Research report. The hidden cost of ‘free’ maternity care in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Health Policy and Planning. 13(4): 1998; 417–422.

- A Soucat, D Levy-Bruhl, Xd Bethune. Affordability, cost-effectiveness and efficiency of primary health care: the Bamako Initiative experience in Benin and Guinea. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 12(S1): 1997; S81–S108.

- JE Lawn, S Cousens, J Zupan. 4 million neonatal deaths: When? Where? Why?. Lancet. 365(9462): 2005; 891–900.

- A Honda. User fee policy and equity funds in Madagascar: an analysis of the design and implementation process from an agency-incentive perspective, in Health Policy Unit. 2009; London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine: London.