Abstract

As part of efforts to achieve Millennium Development Goal 5 – to reduce maternal mortality by 75% and achieve universal access to reproductive health by 2015 – the Malawi Ministry of Health conducted a strategic assessment of unsafe abortion in Malawi. This paper describes the findings of the assessment, including a human rights-based review of Malawi's laws, policies and international agreements relating to sexual and reproductive health and data from 485 in-depth interviews about sexual and reproductive health, maternal mortality and unsafe abortion, conducted with Malawians from all parts of the country and social strata. Consensus recommendations to address the issue of unsafe abortion were developed by a broad base of local and international stakeholders during a national dissemination meeting. Malawi's restrictive abortion law, inaccessibility of safe abortion services, particularly for poor and young women, and lack of adequate family planning, youth-friendly and post-abortion care services were the most important barriers. The consensus reached was that to make abortion safe in Malawi, there were four areas for urgent action – abortion law reform; sexuality education and family planning; adolescent sexual and reproductive health services; and post-abortion care services.

Résumé

Dans le cadre des activités entreprises pour atteindre le cinquième objectif du Millénaire pour le développement – réduire de 75% la mortalité maternelle et rendre universel l'accès à la santé génésique d'ici 2015 – le Ministère de la santé du Malawi a mené une évaluation stratégique des avortements à risque dans le pays. Cet article décrit les conclusions de l'évaluation, notamment un examen, dans l'optique des droits de l'homme, des lois, politiques et accords internationaux du Malawi en matière de santé génésique, et les donnés de 485 entretiens approfondis sur la santé génésique, la mortalité maternelle et les avortements à risque, réalisés avec des Malawiens de toutes les régions du pays et de toutes origines sociales. Pendant une réunion nationale de diffusion, une large base de parties prenantes locales et internationales a défini des recommandations consensuelles pour aborder la question de l'avortement à risque. Les obstacles majeurs étaient constitués par la loi restrictive du Malawi sur l'avortement, l'inaccessibilité des services d'avortement sûr, en particulier pour les jeunes femmes pauvres, et le manque de planification familiale appropriée et de services de soins post-avortement adaptés aux jeunes. Les participants ont convenu qu'il y avait quatre domaines d'action urgente pour rendre les avortements sûrs au Malawi : réforme de la loi sur l'avortement ; éducation sexuelle et planification familiale ; services de santé génésique pour adolescents ; et services de soins post-avortement.

Resumen

Como parte de los esfuerzos para lograr el Objetivo 5 de Desarrollo del Milenio –reducir en un 75% la tasa de mortalidad materna y lograr acceso universal a los servicios de salud reproductiva para el año 2015– el Ministerio de Salud de Malaui realizó una evaluación estratégica del aborto inseguro en Malaui. En este artículo se describen los hallazgos de la evaluación, incluso una revisión basada en los derechos humanos de las leyes, políticas y acuerdos internacionales de Malaui relacionados con la salud sexual y reproductiva y datos de 485 entrevistas a profundidad sobre la salud sexual y reproductiva, mortalidad materna y aborto inseguro, realizadas con malauianos/as de todas partes del país y de todas las clases sociales. Las recomendaciones de consenso para tratar el asunto del aborto inseguro fueron formuladas por una amplia base de partes interesadas a nivel local e internacional durante una reunión de difusión nacional. La restrictiva ley de aborto, la inaccesibilidad de los servicios de aborto seguro, particularmente para mujeres pobres y jóvenes, y la falta de servicios adecuados de planificación familiar, amigables a la juventud y de atención postaborto, fueron las barreras más importantes. Se llegó al consenso de que para lograr que el aborto sea seguro en Malaui, hay cuatro áreas de acción urgente: reforma de la ley de aborto; educación sexual y planificación familiar; servicios de salud sexual y reproductiva para adolescentes; y servicios de atención postaborto.

The word for pregnancy in the indigenous Malawian language of Chichewa is pakati, which translates literally as “the place between life and death”. The association of pregnancy with death in Malawi is not surprising: sub-Saharan Africa accounts for the highest proportion of maternal deaths worldwide, and Malawi has consistently reported one of the highest maternal mortality ratios (MMR) in the world. Most recent figures estimate Malawi's MMR at 510 maternal deaths for every 100,000 live births.Citation1 In spite of the attention generated by Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 5 – to improve maternal health by reducing maternal mortality by three-quarters from 1990 to 2015, and providing universal access to reproductive health by 2015 – progress in reducing maternal deaths has been uneven and unacceptably slow.

Anxious to develop new policies and programmatic interventions to decrease maternal mortality, the Reproductive Health Unit, Malawi Ministry of Health, requested technical and financial support from the UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP) and Ipas, to conduct a strategic assessment on issues related to unsafe abortion, a leading cause of maternal death in Malawi. Such an assessment is the first of a three-stage framework and planning process called the WHO Strategic Approach to strengthening sexual and reproductive health policies and programmes (Strategic Approach).Citation2 The second and third stages include field testing interventions on a limited basis to address the needs identified during the assessment, and scaling-up of successful interventions to benefit more people. Since its introduction in 1993, more than 30 countries have used the Strategic Approach to strengthen policies and programmes on a wide range of sexual and reproductive health issues. Thirteen countries, five in Africa, have applied the Strategic Approach specifically to the issue of unsafe abortion.Footnote*

Unintended pregnancy and unsafe abortion in Malawi

Malawi's current law regulating abortion, a vestige of the antiquated British Offences against the Person Act 1861, imposed under British rule (1891–1964), allows abortion only for preservation of a woman's life.Citation3 In practice, the endorsement of two independent obstetricians is required before abortion can be performed,Citation4 and spousal consent is necessary.Citation5 According to the law, any attempt to procure an abortion is punishable by 7–14 years imprisonment. Many African countries inherited similar restrictive colonial laws regarding abortion. Since the International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo (1994), however, a number have initiated or enacted legal reform, with varying success in establishing safe abortion services.Citation6

In Eastern Africa, where Malawi is located, the rate of unsafe abortion is 36 per 1,000 women aged 15–49 years.Citation7 Unsafe abortion is the second leading cause of pregnancy-related mortality in Malawi, accounting for 18% of all maternal deaths,Citation4Citation8Citation9 and is the leading cause of obstetric complications (24–30%).Citation4Citation10 Malawi has a low contraceptive prevalence rate (41%), high unmet need for contraception (28%),Citation11 high total fertility rate (6.0) and large numbers of mistimed/unwanted pregnancies (40% of births in the five years preceding the 2004 Demographic & Health Survey).Citation12 Malawian women most commonly seek abortion services from private clinics or traditional healers, or attempt to self-induce abortion using unsafe methods.Citation5Citation13

The age of sexual consent is 13 in Malawi;Citation3 the minimum age for marriage is 18, or 15 with parental consent.Citation14 Malawian youth initiate sexual activity and childbearing at a young age: 37% of adolescent girls and 60% of adolescent boys 15–19 years old have had sexual intercourse,Citation5 and a third of young women have begun childbearing.Citation12 Approximately a third of adolescents aged 15–19 years reported having a close friend who tried to end a pregnancy, as did a fifth of those aged 12–14.Citation5 Inadequate knowledge of sexual and reproductive health,Citation15 reluctance to access health services,Citation16 early marriage and sexual debut,Citation17 and low rates of contraceptive use make Malawian teens particularly vulnerable to sexual and reproductive health problems, including complications of unsafe abortion.

Legal and policy framework on abortion in Malawi

The Ministry of Health developed an Essential Health Package in 2001 consisting of 11 cost-effective interventions responding to Malawi's burden of disease. Although the package included reproductive health, treatment of abortion complications and family planning, it was resource- rather than need-driven, and thus was never expected to achieve the MDGs.Citation18 However, it became the vehicle for sector-wide funding for health from several international agencies. A recent evaluation of the package and sector-wide approach determined that services for treatment of complications of abortion in Malawi need to double to meet demand.Citation19

To accelerate attainment of all MDGs, Malawi has implemented the Malawi Growth and Development Strategy 2006–2011,Citation20 which is expected to provide a broad base for poverty reduction, with specific policies to address provision of social services such as health and education, including the 2007 Road Map for Accelerating the Reduction of Maternal and Neonatal Mortality and Morbidity in Malawi (Road Map).Citation21 The Road Map aims to decrease maternal mortality by increasing availability, accessibility, utilization and quality of skilled obstetric care during pregnancy, childbirth and the postnatal period, as well as avoidance of unintended pregnancy and unsafe abortion with family planning. Importantly, the Road Map acknowledges unsafe abortion as a major cause of maternal mortality.

The National Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Policy 2009 (SRHRP)Citation22 provides a rights-based framework for the provision of comprehensive sexual and reproductive health services in accordance with the ICPD Programme of Action. Its goal is to promote, through informed choice, safer reproductive health practices by men, women, and young people, including use of good quality, accessible reproductive health services. It calls for the provision of abortion services to the full extent of the law, prevention of unsafe abortion and management of any complications with high quality post-abortion care services, including counselling, family planning and use of manual vacuum aspiration as appropriate. Safe abortion services are not discussed in any national policy.

Malawi has signed and ratified a number of regional and international human rights treaties and consensus documents relating to abortion. The most important of these include the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), the Maputo Plan of ActionCitation23 and the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (Maputo Protocol).Citation24 The Maputo Protocol, Article 14(2)(c), specifically calls for the enactment of policies and legal frameworks to reduce incidence of unsafe abortion and the provision of abortion on broad-based legal grounds, including “in cases of sexual assault, rape, incest, and where the continued pregnancy endangers the mental and physical health of the mother”, standards at odds with Malawi's current abortion law. In their most recent review of implementation of CEDAW, the CEDAW Committee reiterated its concern regarding Malawi's high maternal mortality, particularly from unsafe abortions. The Committee called for more attention to complications from unsafe abortion, and recommended that Malawi review its abortion laws.Citation25 Malawi is not unique in failing to comply with these international instruments; a number of African countries are struggling with them, whether because of obstacles to reforming restrictive laws or creating enabling environments for provision of services, or both.Citation26

Methods

A Strategic Assessment is a participatory process utilizing qualitative methods that involves a range of multisectoral, multidisciplinary stakeholders in:

| • | planning and preparatory activities; | ||||

| • | two weeks of field-based, iterative data generation and analysis; | ||||

| • | compilation of findings and draft recommendations; and | ||||

| • | a national dissemination workshop to generate consensus on recommendations for follow-up. | ||||

In preparation for the fieldwork, a background paper containing socio-demographic, cultural, political, economic and public health data and research on abortion in Malawi was prepared and disseminated. In addition, a draft version of the WHO Tool on Human Rights and Sexual and Reproductive HealthCitation27 was used to identify and analyse Malawi's national laws, policies, and regulations that facilitate and constrain access to sexual and reproductive health information and services. The background paper informed the assessment planning workshop, held in May 2009, and provided an evidence-based foundation for the fieldwork.

The planning workshop, attended by the strategic assessment team and key stakeholdersFootnote* considered the background information and generated consensus about key questions to guide the fieldwork. The assessment team underwent three days of training in preparation for the fieldwork, consisting of information sharing about clinical, public health and human rights issues related to abortion, interviewing skills, the generation of qualitative data, and the uses of qualitative and quantitative data sources.

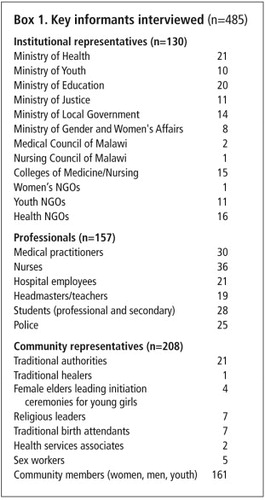

Fieldwork was directed by the Ministry of Health's Reproductive Health Unit, from 14–27 June 2009. A 24-member team, including representatives from Ministry of Health, HRP, NGOs, social scientists, and health care providers, conducted in-depth interviews with 485 people in 10 of Malawi's 28 districtsFootnote* in that period (Box 1

). The 10 districts were selected by the Reproductive Health Unit to capture a diverse sample of Malawians, representing different ethnic groups, living situations, socio-economic status and availability and quality of reproductive health services in Malawi. Purposive and snowball sampling were used to generate data from a broad range of key informants from these districts.In-depth interviews and group discussions with informants focused on two objectives: 1) to elicit unprompted knowledge and perspectives about abortion and related sexual and reproductive health and rights issues; and 2) to provide them with the background data on abortion, if necessary, and engage in discussion on how best to address unsafe abortion in Malawi. During fieldwork, the assessment team reviewed their data at the close of each day, highlighting significant findings, identifying areas where further information was needed and developing overarching themes. Interview guides were modified to build on accumulated knowledge and test the validity of themes in subsequent interviews. Direct quotes from respondents illustrating themes were agreed upon by the team. The validated themes were used to generate consensus around recommendations for specific follow-up actions.

Key findings

Abortion: unsafe and illegal

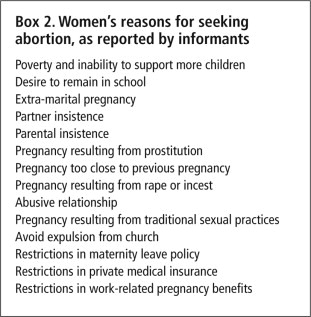

Legal abortion was believed to be rare, provided at the discretion of specialists, available only at the tertiary care level, and entailed cumbersome approval processes. Hence, most informants assumed that almost all abortions were illegal. Similarly, providers interpreted the law conservatively; most reported they would decline to provide an abortion rather than risk providing an “illegal” abortion. Almost no legal abortions were identified during the assessment. Despite this, abortion was extremely common, and was sought for a myriad of reasons (Box 2

). Nearly everyone asked knew someone who had had an abortion.Women seeking abortions in Malawi were found to have two distinct options: those with adequate financial resources, information and/or connections were more likely to utilize relatively safe abortion services, administered secretly by skilled providers in private or public clinics using safe methods. These services were costly (about 5000 Malawian Kwacha, or US$35) and limited to urban areas. However, most women resorted to less safe methods of abortion from unskilled providers, traditional healers or self-induced, based on the advice of friends and family. Numerous methods of unsafe abortion were reported. (Box 3

) The women who used these methods – poor, rural and vulnerable women – shouldered the bulk of morbidity and mortality related to unsafe abortion:“It is all about poverty; the rich are sorted out with their money.” (Sex worker)

“As an employee of [a private clinic], I have performed these abortions. I was doing it as a duty and an obligation. The government knows that private clinics do abortions.” (Nurse)

Deaths due to abortion were common. In a village outside Zomba the local chief reported that eight young girls had died of abortion complications in the space of four months; another village chief near Mulanje reported that five girls had died after unsafe abortions during the same time period; in a single month, four abortion-related deaths were recorded at Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Blantyre. Death and disability related to unsafe abortion had created support for liberalization of the abortion law among many informants, even if only on specific grounds such as rape, incest or preservation of health. A number of policymakers had been unaware that Malawi's abortion law was discordant with ratified international agreements, and supported harmonizing Malawi's law with such agreements. However, everyone who supported law reform believed there would be strong opposition to it, as abortion was highly stigmatized both within the health system and in communities.

“When a woman dies of cholera, the Ministry of Health is shaken, but when a woman dies from unsafe abortion or abortion complications, no one is shaken.” (Clinical officer)

“Those who have abortions should be prosecuted, and if they die they will be judged, wherever they are going.” (Community member)

Post-abortion care

Post-abortion care is provided in most of Malawi's secondary- and tertiary-care health facilities and some primary health centres, which demonstrated the necessary knowledge and attitudes for its provision. Standards and guidelines on quality of care were posted in all but one facility visited. Cases were clearly documented, as was the provision of post-abortion contraception. Facilities reported regularly reviewing services. Demand was high; administrators at one hospital estimated that 60–70% of gynaecology admissions were for complications of unsafe abortion.

However, in many facilities visited, manual vacuum aspiration (MVA), the currently recommended method of uterine evacuation, was not routinely used. Lack of staff caused delays, or patients were referred for sharp curettage under heavy sedation, which carried significantly higher risks and costs.

In most facilities, MVA instruments were lacking in number or quality. MVA aspirators and cannulae were worn, and rusted equipment was observed at some facilities. Health care workers acknowledged these inadequacies but were unable to acquire replacements. Although MVA is on the government's Standard Equipment List,Citation28 many health officials were uncertain about its procurement and cost. In several facilities, MVA equipment was available, but was not used; supplies were locked in cabinets to prevent them being used to induce abortions.

Prevention of unwanted pregnancy

Participants identified prevention of unintended pregnancy as a necessary first step in reducing abortion-related mortality in Malawi. However, contraceptive use was limited by commodity unavailability, misperceptions and fear of contraceptives, gender inequality in contraceptive decision-making, and the belief that contraception should be used only after a first pregnancy.

Contraceptive availability was limited for a number of reasons. Catholic facilities did not provide contraceptives at all; in some cases, their patients received contraceptives through community distribution or health surveillance assistants, but the assessment did not evaluate the extent of such coverage. In facilities offering contraception, health workers were routinely overwhelmed by the numbers of women seeking services; they experienced frequent stock-outs of the most popular methods, especially injectables and implants; and providers lacked training to provide long-acting or permanent methods, such as implants, IUDs and sterilization. Although many health centres had emergency contraceptives, there was little public knowledge of them, and their use was limited and sporadic.

Significant misinformation and fear persisted in the community with regard to contraception, and common misperceptions, such as association with infertility, reduced libido and other health problems limited use. Regardless of age, condom use was strongly associated with promiscuity and prevention of HIV, rather than contraception, and condoms were not used within marriage.

Gender inequality and gendered cultural practices also limited women's ability to use contraceptives. Women interviewed reported an ideal family size of 3–4 children, while men generally desired six or more. Community members and health workers reported that women often required their husband's permission to use contraception, while many husbands discouraged its use for myriad reasons. Some men said they wanted their wives to bear many children to render them less attractive to other men, like a sarong that has become faded due to many washings, and thus more dependent. Withholding contraception was also seen as a way to discourage female promiscuity, as pregnancies conceived outside marriage (whether through sexual cleansing rituals for widows, transactional sex, or other reasons) were often condemned.

Adolescent pregnancy and abortion

Sexual activity, pregnancy and marriage at an early age were not uncommon. Particularly in rural areas, Malawian girls were frequently mothers and married before the end of adolescence. Pregnancy during adolescence comes at a cost to girls, as it is grounds for expulsion from school. Participants estimated that 20–30% of girls left school due to pregnancy and, although recent legislation allows them to return two years later, educators reported that few did so. In a small village in southern Malawi, the local primary school headmaster reported that in the 12 months preceding the assessment, 56 girls had been dismissed for pregnancy. In some schools, girls were regularly physically examined to identify those who were pregnant. Although the dismissal policy also applied to boys, no cases of expulsion of boys were identified during the assessment. Desire to remain in school was cited as a common reason why adolescent girls sought abortions.

Despite high rates of adolescent pregnancy, sexual education and youth-friendly reproductive health services were lacking. Open discussion of sex and sexuality was limited. Although most parents favoured sexuality education, they felt uncomfortable discussing sex with their own children. Similarly, community members reported that informal discussions about sex were considered appropriate only for those who were married. An important exception were pubertal initiation ceremonies carried out in some communities and ethnic groups, typically presided over by a female elder. Intended to prepare girls for marriage, they included instruction in cooking, housekeeping, and sexual relations. Some initiation ceremonies encouraged sexual relations at a very young age, even before the legal age of consent and without concomitant education on prevention of pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections. According to one community member, in the south of the country, adult men were brought into these ceremonies to have sex with the girls, sometimes leading to pregnancy. In several communities, young women reported that after initiation they were aggressively pursued for sex, as they were now considered sexually mature. Participants disagreed about the prevalence of such practices, which had been discouraged by HIV/AIDS prevention programmes.

Adolescents reported acquiring sexuality education largely from their peers and at school. School-based sexuality education is contained in Malawi's Life Skills Curriculum, which emphasizes HIV/AIDS prevention, but gives little information on other STIs, contraceptives or unwanted pregnancy, and no information about abortion. At the time of the assessment, the curriculum had been implemented only sporadically. Educators uniformly reported that they were uncomfortable with the material and inadequately trained to teach it.

To more effectively address the health needs of adolescents, a programme of youth-friendly services was initiated by the Malawian health system in 2007, but has had little success in providing contraceptives or sexual and reproductive health education to young people. Individual health care facilities, in particular district hospitals, have had varying success in implementing this programme, if at all. In several facilities visited, minimal services were typically available from one provider for a limited number of hours. However, in several facilities, a strong effort had been made to address the needs of youth, which involved several specially trained providers, frequent educational talks or demonstrations, at times conducted by peers, and movies, games or other incentives intended to attract youth to the centres. All services were limited by several factors: most centres were located in the clearly demarcated family planning areas of the public hospital or in areas frequented by adults; services offered little or no privacy or confidentiality (due in part to their location); and most were run by staff whom teens were unable to relate to, or who were unable to relate to teens, either due to age differences or negative attitudes towards adolescent sexuality.

“The parental instinct makes a health worker start tormenting young people with advice that they should abstain and not indulge in sex, yet the young person has come for these services.” (Ministry of Health employee)

The dissemination meeting and its recommendations

During the strategic assessment informants indicated that safe abortion was not part of the culture of Malawi; yet a recent study shows that the rate of abortions in Malawi is 38 per 1,000 women of reproductive age,Citation29 compared to the global average of 29 per 1,000. Despite the restrictive abortion law, many women seek abortions, and often suffer life-threatening consequences when they are unsafe.

The findings of the assessment and recommendations developed by the assessment team were presented at a national dissemination meeting, opened by the Minister of Health in August 2010. Participants included representatives from relevant government agencies including policymakers, programme managers, health service providers, national and international NGOs, UN agencies, sexual and reproductive health advocates, and local human rights organizations. Based on the assessment findings, this diverse group of Malawians agreed that morbidity and mortality due to unsafe abortion presented a significant problem for their country, and they developed consensus recommendations in four areas, detailed below, that need to be urgently addressed in order to eliminate unsafe abortion in Malawi. A core group of national stakeholders, hosted by the NGO Women in Law in Southern Africa, has since formed the Coalition for the Prevention of Unsafe Abortion in Malawi, to advocate for implementation of the following key recommendations:

• Review and reform Malawi's restrictive abortion law

In countries where legal restrictions on abortion have been reduced or removed and safe services become available, such as South Africa, USA and Romania, maternal mortality and abortion-related complications have declined dramatically.Citation30–32 The dissemination meeting recommended harmonizing Malawi's abortion law with the Maputo Protocol, with additional legal grounds to facilitate adolescents' access to safe abortion. They recognized the cultural and religious sensitivity of allowing abortion at the request of the woman; however, they argued that it will require a liberal interpretation of mental and physical health grounds for legal abortion to ensure equitable access for poor and young women.

They recommended initiation of an evidence-driven, national discussion on unsafe abortion, its contribution to maternal mortality and implications for reforming the current abortion law – to help to mitigate what will surely be a contentious national debate. However, only after domestication of the Maputo Protocol and related legislative reform will the Government be able to focus on strengthening service delivery, which will ultimately reduce abortion-related injuries and deaths. Further, in order to be effective, a liberalised law will require adequate community and health care provider education, development of standards and guidelines for abortion care, ready availability and access to safe, legal abortion services, and a change in gendered attitudes toward sexuality and reproduction.

Recent statements by Malawi's former Secretary of Health Chris Kang'ombe, that the government has no plans to legalise abortion, underscore the extent of likely resistance to legal reform.Citation33

• Strengthen the national family planning programme

Adequate provision of family planning is an important strategy for preventing unwanted pregnancy and reducing maternal mortality related to unsafe abortion.Citation34 Better sexuality education could dispel widespread misperceptions about contraceptives and change attitudes that discourage use of contraception prior to a first pregnancy. Government actions are required to eliminate administrative barriers and ensure continuous procurement and distribution of contraceptives in all public health facilities. Meeting participants strongly recommended expanding provision of contraceptives, particularly injectables, by community-based workers, a program in pilot testing at the time of the assessment. Furthermore, efforts to train health personnel to provide permanent and longer-acting contraceptives such as implants, IUDs and sterilization must be strengthened.

• Address the sexual and reproductive health needs of young Malawians

In 2009, the Committee on the Rights of the Child recommended to the State of Malawi to increase its efforts to establish more child-friendly programmes and services in the area of adolescent health, to obtain valid data on adolescent health and adopt an effective and gender-sensitive strategy of education and awareness-raising for the general public, with a view to reducing the incidence of teenage pregnancies.Citation35 Lack of information and youth-friendly services, inability to access the services that do exist, and the poor performance of those services leave sexually active adolescents with few options to protect themselves from STIs and unintended pregnancy.Citation5 Malawi's youth are particularly vulnerable to the consequences of harmful norms and practices such as early marriage, pregnancy leading to expulsion from school, low contraceptive use, and inadequate sexuality education. The teen pregnancy rate in Malawi is 35%,Citation11 and young people aged 15–24 experience the highest rates of new HIV infection in the country.Citation5 The meeting recommended that the Life Skills Curriculum be revised to address issues of unintended pregnancy, STIs, and abortion. Furthermore, health care providers need to be adequately trained to serve youth, and reproductive health services should be made accessible and acceptable to youth, with appropriate measures to ensure privacy.

• Strengthen post-abortion care services

Even though Malawi has made great inroads in the provision of post-abortion care, further improvement is required in many areas. The Ministry of Health should continue its efforts to expand these services in primary level health facilities, in line with the 2009 National SRHRP.Citation22 MVA should replace sharp curettage for treatment of incomplete abortion.Citation9 Worn out MVA equipment should be replaced. Women seeking post-abortion care should not be stigmatized or subjected to lengthy delays in receiving care, particularly at night and during weekends. Despite the need to strengthen these services, policymakers must realize that while post-abortion care can save lives by treating complications, it cannot offer the same protection of health and life as safe, legal abortion.

Conclusion

There is growing recognition in Malawi that reaching the MDG 5 targets by 2015 will be impossible without addressing unsafe abortion. Malawi's policymakers have demonstrated their understanding of the need to tackle unsafe abortion through the regional treaties and consensus documents they have signed and their own national policies, and by requesting external assistance to help them combat the public health tragedy of unsafe abortion. Following the strategic assessment, a group of national women's health and human rights advocates have mobilized to help generate the political will required for bolder actions. However, further progress is unlikely without reform of Malawi's restrictive abortion law and subsequent provision of safe abortion services – essential not only for Malawi but also most other African countries.

Acknowledgements

The strategic assessment and related workshops were funded by Ipas. HRP funded the technical support from its staff members Emily Jackson, Ronald Johnson and Eszter Kismodi. Special thanks to fellow Strategic Assessment team members: Egglie Chirwa, Andrew Gonani, Darlington Harawa, Fanny Kachale, Tinyade Kachika, Francis Kamwendo, Grant Kankhulungo, Hans Katengeza, Edfas Mkandwire, Errol Nkonko, Awah Paschal, Leonard Banda, Evelyn Chitsa Banda, Mary Busile, Wanangwa Chimwaza, Edgar Kuchingale, Chembezi Mhone, MacDonald Msadala, Dorothy Nyasulu. We also thank Eunice Brookman-Amissah, Ipas Vice President for Africa, for ongoing support; Eszter Kismodi for technical support with the WHO Human Rights Tool; and Peter Fajans for contributions to the draft manuscript.

Notes

* Bangladesh, Ghana, Guinea, Macedonia, Malawi, Moldova, Mongolia, Romania, Russia, Senegal, Ukraine, Viet Nam, and Zambia.

* Attended by representatives from: national and regional offices of the Ministry of Health; Malawi Human Rights Commission; Centre for Reproductive Health; Banja La Mtsogolo; National Youth Council; obstetricians and gynaecologists in public and private practice; Nurses and Midwives Association of Malawi; Parliamentary Committees on Health and Legal Affairs; Christian Hospitals Association of Malawi; Medical Council of Malawi; Ministry of Justice; Ministry of Women and Child Development and Community Services; UNFPA; WHO; HRP; DFID; UNICEF; Family Planning Association of Malawi; Women's Parliamentary Caucus; Ministry of Education; Forum for African Women Educationalists in Malawi; National NGO Gender Network; Malawi High Court; Malawi White Ribbon Alliance for Safe Motherhood; Malawi Health Equity Network; Ipas.

* Blantyre, Dowa, Lilongwe, Mangochi, Mulanje, Mzimba, Nkhatabay, Nkhotakota, Ntcheu, Zomba.

References

- World Health Organization. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2008. Estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and World Bank. 2010; WHO: Geneva.

- World Health Organization. The WHO Strategic Approach to strengthening sexual and reproductive health policies and programmes. 2007; WHO: Geneva.

- Malawian Penal Code. Laws of Malawi. Chapter 7:01; 1930.

- Sharan M, Saifuddin A, Malata A, et al. Quality of maternal health system in Malawi: are health systems ready for MDG5? Africa Human Development, World Bank, and Kamuzu College of Nursing, University of Malawi, 2010.

- A Munthali, E Zulu, N Madise. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health in Malawi: Results of the 2004 national survey of adolescents. Occasional Report No.24. 2006; Guttmacher Institute: New York.

- E Brookman-Amissah, JB Moyo. Abortion reform in sub-Saharan Africa: no turning back. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24 Suppl.): 2004; 227–234.

- World Health Organization. Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2008. 2011; WHO: Geneva.

- E Geubbels. Epidemiology of maternal mortality. Malawi Medical Journal. 18(4): 2006; 206–225.

- Malawi Ministry of Health; Ipas. Study on the magnitude of unsafe abortion in Malawi. National Dissemination Meeting on Unsafe Abortion in Malawi. Lilongwe, 18–19 August 2010.

- Malawi Ministry of Health. Emergency obstetric care services in Malawi: report of a nationwide assessment. Malawi MoH; 2005.

- Malawi National Statistics Office; UNICEF. Malawi Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2006: Final report. 2008; NSO; UNICEF: Lilongwe.

- National Statistical Office Malawi; ORC Macro. Malawi Demographic & Health Survey 2004. 2005; NSO; ORC Macro: Calverton, MD.

- Family Planning Association of Malawi. Magnitude, views and perceptions of people on abortion and post abortion in four Malawian districts. Unpublished report; 2007.

- Government of Malawi. The Constitution of the Republic of Malawi, section 22. 1995.

- VM Lema. Reproductive awareness behavior and profiles of adolescent post-abortion patients in Blantyre, Malawi. East African Medical Journal. 80(7): 2003; 339–344.

- A Biddlecom, A Munthali, S Singh. Adolescents' views of and preferences for sexual and reproductive health services in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Malawi and Uganda. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 11(3): 2007; 99–110.

- National Youth Council of Malawi. Report on profiling early marriages in Malawi. Lilongwe; 2009.

- D Gwatkin, E Kataika, I Cardinal. Malawi's Health SWAp: bringing essential services closer to the poor?. Malawi Medical Journal. 18(1): 2006; 1–4.

- C Bowie, T Mwase. Assessing the use of an essential health package in a sector-wide approach in Malawi. Health Research and Policy Systems. 9: 2011; 4.

- Government of Malawi. Malawi growth and development strategy 2006–2011. 2006; Government of Malawi: Lilongwe.

- Malawi Ministry of Health. Road map for accelerating the reduction of maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity in Malawi. 2007; MoH: Malawi.

- Malawi Ministry of Health. National Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Policy. 2009; MoH: Malawi.

- African Union Commission. Plan of action on sexual and reproductive health and rights. Special Session of the African Union Conference of Ministers of Health. Maputo, 18–22 September 2006.

- African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights. Protocol to the African charter on human and peoples' rights on the rights of women in Africa. Article 14, Health and reproductive rights. Maputo: Second Ordinary Session of the Assembly of the Union; 2003.

- CEDAW. Concluding observations of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, Malawi. CEDAW/C/MWI/CO/6; 2010. Paras 36–37.

- C Ngwena. Protocol to the African Charter on the Rights of Women: implications for access to abortion at the regional level. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 110: 2010; 163–166.

- World Health Organization. Using human rights to advance sexual and reproductive health: a tool for examining laws, regulations and policies. Geneva: WHO Press; forthcoming.

- Malawi Ministry of Health. Standard equipment list for typical district and community hospital and health centre with generic specifications for some common and general equipment. 2009; MoH: Lilongwe.

- Malawi Ministry of Health; Ipas. Study on the magnitude of unsafe abortion in Malawi. National Dissemination Meeting on Unsafe Abortion in Malawi. Lilongwe, 18–19 August 2010.

- BR Johnson, M Horga, P Fajans. A strategic assessment of abortion and contraception in Romania. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24 Suppl): 2004; 184–194.

- LA Bartlett, CJ Berg, HB Shulman. Risk factors for legal induced abortion-related mortality in the United States. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 103(4): 2004; 729–737.

- R Jewkes, H Rees, K Kickson. The impact of age on the epidemiology of incomplete abortions in South Africa after legislative change. BJOG. 112: 2005; 355–359.

- Government aborts abortion. Malawi Voice. 8 June 2010. At: <http://malawivoice.com/national-news/government-aborts-abortion/?wpmp_tp=0. >. Accessed 27 March 2011.

- S Singh, J Darroch, L Ashford. Adding it up: the costs and benefits of investing in family planning and maternal and newborn health. 2009; Guttmacher Institute; UNFPA: New York.

- CRC. Concluding observations of the Committee on the Rights of the Child, Malawi. CRC/C/MWI/CO/2; 2009. Paras 54–55.