Abstract

In low-income countries, the coverage of institutional births is low. Using data from the two most recent Demographic and Health Surveys (1995–2001 and 2001–2006) for 25 low-income countries, this study examined trends in where women delivered their babies – public or private facilities or non-institutional settings. More than half of deliveries were in institutional settings in ten countries, mostly public facilities. In the other 15 countries, the majority of births were in women's homes, which was often their only option. Between the two survey periods, all five Asian countries studied (except Bangladesh) had an increase of 10–20 percentage points in institutional coverage, whereas none of the 19 sub-Saharan African countries saw an increase of more than 10 percentage points. More urban women and more in the richest (least poor) quintile gave birth in public or private facilities than rural and poorest quintile women. The rich–poor gap of institutional births was wider than the urban–rural gap. Inadequate public investment in health system infrastructure in rural areas and lack of skilled health professionals are major obstacles in reducing maternal mortality. Governments in low-income countries must invest more, especially in rural maternity services. Strengthening private, for-profit providers is not a policy choice for poor, rural communities.

Résumé

Dans les pays à faible revenu, la couverture des naissances institutionnelles est faible. Se fondant sur les données des deux plus récentes enquêtes démographiques et sanitaires (1995–2001 et 2001–2006) pour 25 pays à faible revenu, cette étude a examiné l'évolution des lieux d'accouchement : maternités publiques et privées ou sites non institutionnels. Dans dix pays, plus de la moitié des naissances se produisaient dans une institution, principalement publique. Dans les 15 autres pays, la majorité des accouchements avait lieu au domicile de la mère, souvent la seule option. Entre les deux périodes d'enquête, les cinq pays asiatiques étudiés (à l'exception du Bangladesh) ont enregistré une augmentation de 10–20 points de pourcentage de la couverture institutionnelle, alors qu'aucun des 19 pays d'Afrique subsaharienne n'a connu une hausse supérieure à 10 points de pourcentage. Les femmes urbaines et dans le quintile le plus riche accouchaient davantage dans des maternités publiques ou privées que les femmes rurales ou dans le quintile inférieur. Pour les naissances institutionnelles, l'écart entre riches et pauvres était plus large qu'entre zones urbaines et rurales. L'insuffisance des financements publics pour l'infrastructure sanitaire des zones rurales et le manque de professionnels qualifiés sont les principaux obstacles pour réduire la mortalité maternelle. Les gouvernements des pays à faible revenu doivent investir davantage, en particulier pour les services ruraux de maternité. Renforcer les prestataires privés et à but lucratif n'est pas un choix politique pour les communautés rurales pauvres.

Resumen

En países de bajos ingresos, la cobertura de nacimientos institucionales es baja. Utilizando los datos de las últimas dos Encuestas Demográficas y de Salud (1995–2001 y 2001–2006) realizadas en 25 países de bajos ingresos, este estudio examinó las tendencias en cuanto a los lugares donde las mujeres dan a luz: en unidades públicas o privadas, o en entornos no institucionales. Más de la mitad de los partos ocurrieron en ámbitos institucionales en diez países, principalmente en unidades públicas. En los otros 15 países, casi todos los partos fueron domiciliarios, a menudo la única opción. Entre los dos períodos de la encuesta, los cinco países asiáticos estudiados (excepto Bangladesh) vieron un aumento de 10 a 20 puntos porcentuales en cobertura institucional, mientras que en ninguno de los 19 países africanos subsaharianos hubo un aumento de más de 10 puntos porcentuales. Más mujeres urbanas y más en el quintil más rico dieron a luz en unidades públicas o privadas que mujeres rurales y del quintil más pobre. La brecha entre partos institucionales de ricas y pobres fue mayor que la brecha urbana-rural. Inadecuadas inversiones públicas en la infraestructura del sistema de salud en zonas rurales y la falta de profesionales de la salud calificados son los principales obstáculos para disminuir la mortalidad materna. Los gobiernos en países de bajos ingresos deben realizar mayores inversiones, especialmente en servicios rurales de maternidad. Fortalecer a prestadores de servicios particulares, con fines de lucro, no es una opción de políticas para las comunidades pobres rurales.

Low-income countries are facing difficulties in reaching the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) for maternal and child health. Globally, the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) fell from about 400 per 100,000 live births in 1980 to about 260 in 2008.Citation1Citation2 However, it remains unacceptably high across much of the developing world. Only ten of 87 countries with MMRs over 100 in 1990 are on track with annual declines of 5.5% or more. The annual percentage decrease was lowest in sub-Saharan Africa – 1.7% compared to 2.3% for all developing regions.Citation2

In 2008, 358,000 women died from complications of pregnancy, childbirth and unsafe abortion, down from 546,000 in 1990. Ninety-nine per cent of these deaths took place in developing countries, with sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia accounting for 86% of them.Citation2 In sub-Saharan Africa, a woman's risk of dying from treatable or preventable complications of pregnancy and childbirth over the course of her lifetime is 1 in 22, compared to 1 in 7,300 in developed countries.Citation3

In developing countries, the public and private health sectors and “informal” and unqualified traditional healers or birth attendants all provide maternity services. The international literature usually compares health expenditure on public vs. private providers as a proxy for health care utilisation. However, this does not capture real utilisation, as there are differences in fees charged between public and private providers.Citation4 Moreover, it is often assumed that the major share of private expenditure captures the dominant role of private utilisation when, in relation to delivery care, so many women deliver with traditional attendants, who should not be mixed together with private sector clinicians or hospitals.

To capture the actual public and private utilisation of health services in resource-poor countries, particularly for childbirth, estimates should rely on direct surveys of households. The internationally standardised Demographic and Health Surveys (DHSs) can serve this purpose. A recent analysis of DHS data found low coverage by maternity services among poor and rural women in developing countries,Citation5 despite a large proportion of treatment for childhood illnesses being provided by the private sector.Citation6–8 Private providers also played a dominant role in family planning service provision in middle-income countries.Citation9

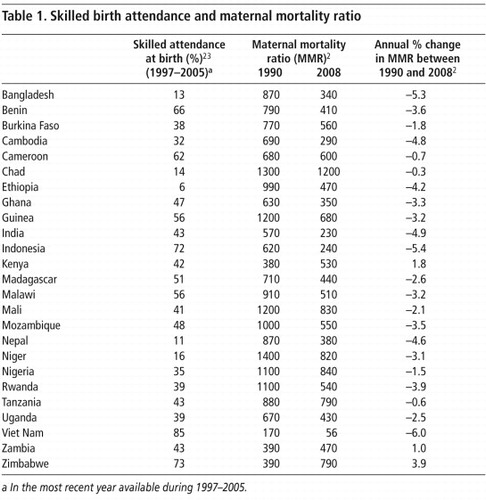

The proportion of institutional deliveries in the 25 low-income countries (Table 1

Table 1 Citation23

Using DHS data from 25 low-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa and South and South-east Asia, this paper shows the proportion of deliveries by public and private facilities and non-institutional care. It then looks at whether these countries had any improvement in institutional delivery between the two survey periods (1995–2001 and 2001–2006). It then calculates the gap in coverage with respect to rural–urban location and economic status of women's households between the highest and lowest quintiles.

Methods

The two sets of DHS surveys used in this study covered the period 1995 to 2006. There were 25 countries for which at least two recent DHSs were available; 19 were in sub-Saharan Africa and six in South and South-east Asia. Table 2

lists the years of the two adjacent DHS surveys in the 25 countries.In the DHS, delivery care was selected and probed for the type of providers, based on the following survey questions: “Who assisted with the delivery of (NAME)?”; “Anyone else?”; and “Where did you go to give birth to (NAME)?”

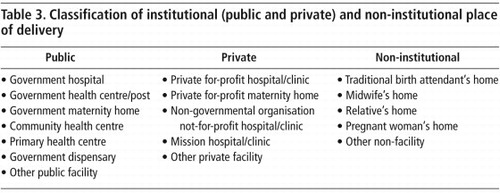

In this study, providers were categorised as institutional (public and private); and non-institutional (Table 3

). The public providers were in health facilities under the jurisdiction of national or local government. The private providers were well-defined commercial, for-profit entities and non-governmental organisations, foundations or missions. The non-institutional deliveries took place in women's own homes or those of friends or relatives, assisted by unqualified providers, such as traditional birth attendants.Each question in the DHS allowed multiple providers to be indicated per delivery. A woman with up to six possible deliveries (except for Guinea and Rwanda in 2005, with up to four and five deliveries, respectively) per round of survey was taken as the unit of analysis. To make the classification mutually exclusive, the analysis applied the following algorithm in assigning the provider type to each respondent:

| • | at least one delivery at public facilities was classified as “public”; | ||||

| • | at least one delivery at private facilities without any public deliveries was classified as “private”; and | ||||

| • | delivery at neither public nor private facilities was classified as “non-institutional”. | ||||

For a delivery where multiple providers were indicated, the above order of algorithm would bias the delivery coverage identified more in favour of public facilities than private facilities and non-institutional care. That is, the non-institutional coverage would be the lowest possible estimates. As such, this paper did not overvalue the prevailing role of the informal and private sectors.

For an analysis of variation within each country in delivery coverage, we chose urban and rural areas to assess the geographic gap, and the highest and lowest quintiles, based on a household asset index, for the economic gap. An absolute difference in the percentage (%) coverage between the two subgroups was presented as percentage points.

For the household asset index, we used the following characteristics: main source of drinking water; type of house floor, toilet facility and cooking stove; and durables such as clock, radio, television, telephone, bicycle, motorcycle and electricity. The households with access to safe drinking water, permanent floor, sanitary toilet and the presence of belongings were considered economically better off than those without. Calculation of the asset index was based on a principal component analysis. To represent the whole country, all analyses accounted for the sampling weights of individual women in each country.

Findings

Coverage and trends in institutional delivery

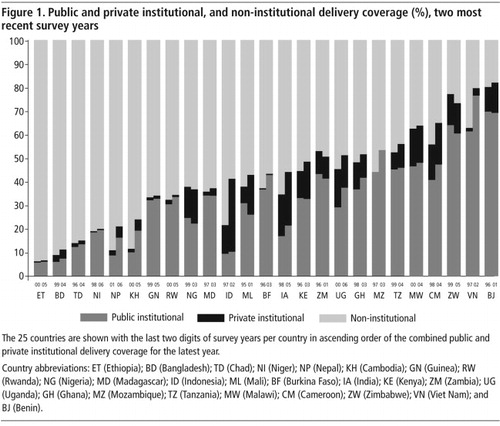

In the 2001–06 DHSs, 51–82% of women in 10 out of 25 countries had institutional deliveries, mostly in public facilities. Institutional deliveries in Zimbabwe, Benin and Viet Nam accounted for 60%, 69% and 76% of all deliveries, respectively (

).Between 1995 and 2006, all five Asian countries studied (except Bangladesh) had a 10–20 percentage point increase in institutional coverage, though, except in Viet Nam, it was still less than half of total deliveries. India and Indonesia had a rapid growth, mostly in private facility deliveries, 6 and 19 percentage points respectively, while Nepal, Cambodia and Viet Nam expanded institutional delivery in public facilities by 8–15 percentage points. None of the 19 sub-Saharan African countries had more than a 10 percentage point increase in institutional deliveries, and Zimbabwe, Zambia and Nigeria had a decrease of 1–4 percentage points.

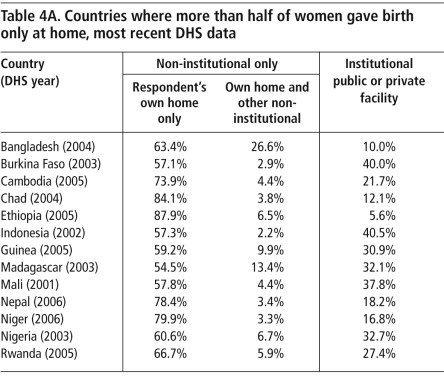

The majority of deliveries in the remaining 15 countries were non-institutional, with the coverage relatively stable over the two survey periods. Ethiopia, Bangladesh, Chad and Niger were among the countries with the lowest institutional deliveries (<20%). Delivery at women's homes was the only option for more than half the women in 13 countries (Table 4A

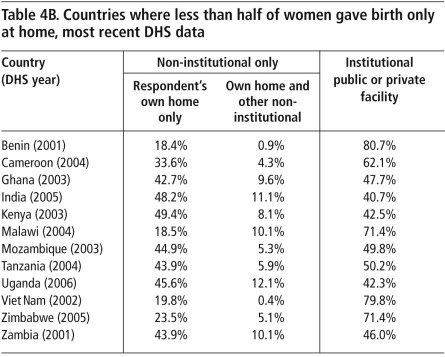

). In Nepal, Niger, Chad and Ethiopia, 78–88% of women gave birth at home. Noticeably, less than 20% of deliveries in these four countries took place in public or private facilities. In contrast, countries where less than half the women gave birth at home tended to have a large institutional coverage (Table 4B ). For example, Benin and Viet Nam had 80.7% and 79.8% institutional deliveries, respectively.Urban–rural and rich–poor differentials

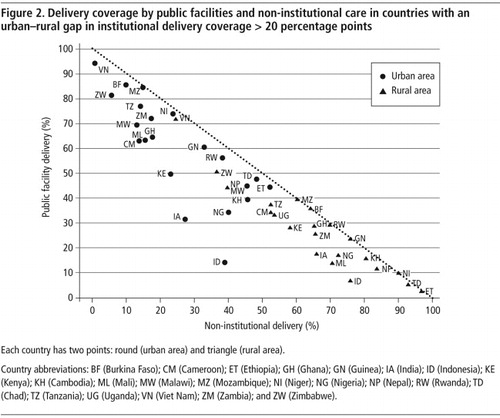

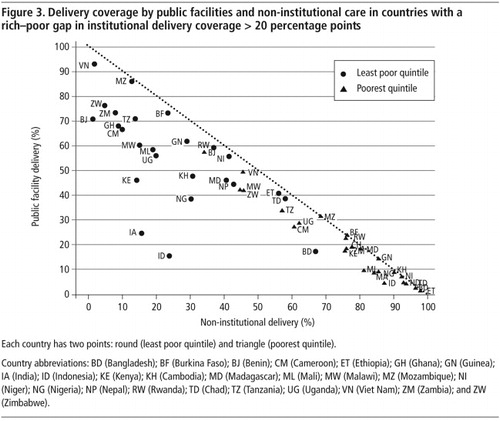

depicts 22 countries in the latest DHS where there was a sizable absolute difference of more than 20 percentage points between urban and rural areas in total public and private institutional deliveries. Similarly depicts all 25 countries with a more than 20 percentage point difference between the top (the least poor) and bottom (the poorest) quintiles of women in total institutional deliveries.

In both figures, the percentage on the vertical axis represents public institutional deliveries, while the horizontal axis represents coverage of non-institutional deliveries. The vertical distance between the two different (round and triangle) dots of the same country captures the gap in the institutional deliveries by public providers and the horizontal distance captures the gap in the non-institutional deliveries. The vertical distance from the 45-degree diagonal line represents private institutional deliveries; the further the distance from the diagonal line, the higher the percentage of private institutional deliveries. Countries that lie on the diagonal axis show no role for private institutional care.

A common theme emerged from the analysis of the urban–rural and rich–poor gaps in institutional delivery coverage. Women living in urban areas and with the top quintile of household wealth had a greater share of delivery in the public and private facilities, whereas their rural and poorest wealth quintile counterparts relied more on non-institutional delivery.

Within the same country, most urban mothers tended to have public institutional deliveries; with the exception of Indonesia and India, where most had private institutional deliveries (). The majority of their rural counterparts relied more on non-institutional delivery. The five countries experiencing the widest urban–rural gap in total institutional delivery, in favour of urban women, were Niger (66 percentage points), Mali (55 percentage points), Burkina Faso (54 percentage points), Zambia (48 percentage points) and Ghana (47 percentage points). The geographic gap in these five countries was driven largely by limited access to delivery in public health settings among the rural population, ranging from only 10% access to public deliveries in Niger to 36% in Burkina Faso.

Regarding the rich–poor gap (), women in the top quintile had most of their deliveries in public facilities (upper left), whereas the poorest quintile women had more non-institutional deliveries (lower right). The five countries with the widest rich–poor gap in institutional delivery were India (69 percentage points), Ghana (68 percentage points), Zambia (68 percentage points), Indonesia (63 percentage points) and Mali (62 percentage points). The economic gap in India and Indonesia was driven largely by the high coverage by the private sector (52–53 percentage points), whereas that in Ghana, Zambia and Mali was driven largely by the high coverage in the public sector (48–55 percentage points). The institutional delivery coverage among the poorest quintile of women in these five countries was low, 3–9% in the private sector and 5–19% in the public sector.

All 25 countries had a rich–poor gap in institutional delivery coverage greater than 20 percentage points, ranging from 29 percentage points in Malawi to 69 percentage points in India. Twenty-two countries (Bangladesh, Benin and Madagascar excluded) had an urban–rural gap greater than 20 percentage points, ranging from 24 percentage points in Viet Nam to 66 percentage points in Niger.

For most countries, the rich–poor gap was wider than the urban–rural gap. For example, in Indonesia in 2002 and India in 2005, private sector facilities played a major role in the delivery of care for the economically well off and urban subgroups, and the economic gap (63–69 percentage points) was almost two times that of the urban–rural gap (37–39 percentage points). Even in Viet Nam in 2002 with the dominance of public facilities, the rich–poor gap (44 percentage points) was also much wider than the urban–rural gap (24 percentage points).

Discussion

Findings from this analysis reaffirm the continuing high prevalence of non-institutional deliveries in low-income settings, in particular in the 13 countries in Table 4A, where more than half the births were delivered in women's own homes, with no access to emergency care if complications arose.

Using the benchmark of 2.28 doctors, nurses and midwives per 1,000 population as the health personnel threshold needed to reach 80% coverage by skilled birth attendants, as per the 2006 World Health Report,Citation11 all 25 countries in this analysis had a human resources crisis. The five among them with the most critical shortages were Ethiopia, Niger, Chad, Mozambique and Tanzania. Moreover, national averages do not expose the extent of maldistribution of existing health professionals, in which most of them are concentrated in urban areas and missing at rural health posts.

Given the situation of extreme scarcity of health personnel in these countries, particularly for women in rural areas and those in the lowest wealth quintile, non-institutional providers have continued to play a significant role in health service provision, and not only for deliveries. It is the major role of untrained, non-institutional birth attendance that has most hampered achievements towards MDG 5. This is the result of two failures. First, the global community and national governments have failed to meet their commitments and responsibilities for health. Most of the sub-Saharan African nations have failed to allocate anything like 15% of their national budgets to health, as committed in 2001.Citation12 And donor countries have failed to contribute 0.7% of their GDP for official development assistance. Moreover, it is not always clear whether the funding they have provided has been used effectively and in an evidence-based way. Funding from various Global Health Initiatives were disease-oriented in favour of HIV/AIDS and not maternal and health services.Citation13

Second, both donors and most low-income countries have failed to comply with the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness. Donors have failed to harmonise their funding in line with developing countries' own priorities, and developing country governments often have limited capacity for managing donor-funded programmes. As BererCitation14 and Gostin et alCitation15 have argued, governments in low-income countries and international development partners are accountable for ensuring adequate access to quality reproductive health services. Adequate numbers and equitable distribution of health workers, financial resources, infrastructure of health delivery systems, and availability of essential medicines are all vital components for achieving the health MDGs.Citation16

While the rich–poor gap was greater than the urban–rural gap, both are significant barriers to accessing health services, and not just maternity care. Not only was delivery in a public health clinic not available for many women, but the cost of public health services and travelling to access them in an urban area was prohibitive. Furthermore, private services were not well developed in rural areas, due both to weak purchasing capacity of rural populations and the unwillingness of health professionals to work rurally.

There are two broad policy choices available to low-income countries to increase the capacity of their health systems: strengthening public financing of the public health system and increasing provision, and engaging private providers to expand the private sector to increase provision.

An example of strengthening public financing is the Ugandan government's unified health sector plan with donor-supported, pooled funding and termination of user charges. This resulted in a significant expansion in public provision and deployment of health personnel, such that the proportion of the population living within a 5 km radius of a clinic increased from 49% to 72%. The salaries of the lowest grades of nurses were also doubled. This resulted in falls in both infant and maternal mortality.Citation17

Timor-Leste's pooled aid, through a sector-wide approach, enabled rapid rehabilitation of the public health system and the implementation of free, universal health care. The coverage of basic health services within a two-hour travelling distance increased from 75% in 2001 to 86% in 2004. The health service utilisation rate increased from one annual visit per person to 2.5 visits. Immunisation of the third dose of DTP vaccine increased from 34% in 2001 to 73% in 2004, and skilled birth attendance increased from 26% to 41%.Citation18

Engaging the private for-profit sector should take into account the challenging prerequisite of increased government capacity to effectively regulate this sector, including command and control, self-regulation by professional bodies, and the role of insurance agencies through incentives and competitive contractual relationships between purchasers and health care providers. Often, government regulatory capacity is severely lacking in low-income and even in middle-income countries.Citation19 Civil society and consumer protection organisations can play a significant role in helping to ensure that public voices are heard and policy action taken accordingly. These prerequisites have yet to be developed in low-income countries.Citation20

As the poor quality and limitations of non-institutional delivery are major concerns, there must be greater public stewardship in monitoring and licensing, in order to ensure adequate quality.Citation21 Government capacity and effectiveness in regulating non-institutional providers in most of these same countries is still weak.Citation22

Conclusions

Two main conclusions must be drawn: fragile health systems that result from inadequate public investment in health system infrastructure in rural areas, and lack of skilled and trained health professionals are among the major impeding factors in reducing maternal mortality. Honouring commitments by governments and international development partners is an important entry point for health systems strengthening. Strengthening private, for-profit providers is not a policy choice for poor, rural communities.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Rockefeller Foundation and the secondment of Prince Mahidol Award Conference 2009 for SL to World Bank and Rockefeller Foundation, for whom extensive analyses of DHS datasets were conducted. Access to DHS data provided by Macro International Inc (MEASURE DHS) is appreciated.

References

- MC Hogan, KJ Foreman, M Naghavi. Maternal mortality for 181 countries, 1980–2008: a systematic analysis of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 5. Lancet. 375: 2010; 1609–1623.

- World Health Organization. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2008. Estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and the World Bank. 2010; WHO: Geneva.

- Are we on track to meet the MDGs by 2015? Tracking the MDGs. At: <www.undp.org/mdg/progress.shtml. >. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- World Health Organization. World Health Report: health systems financing, the path to universal coverage. 2010; WHO: Geneva.

- DR Gwatkin, S Rutstein, K Johnson. Socio-economic differences in health, nutrition, and population within developing countries. 2007; World Bank: Washington, DC.

- D Gwatkin, S Rutstein, K Johnson. Socio-economic differences in health, nutrition, and population. 2000; World Bank: Washington, DC.

- F Bustreo, A Harding, H Axelsson. Can developing countries achieve adequate improvements in child health outcomes without engaging the private sector?. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 81: 2003; 886–895.

- T Marek, C O'Farrell, C Yamamoto. Trends and opportunities in public—private partnerships to improve health service delivery in Africa. Africa Region Human Development Working Paper Series. 2005; World Bank: Washington, DC.

- PSP-One. State of the private health sector. Wall chart. 2005; US Agency for International Development: Washington, DC.

- United Nations Children's Fund. State of the World's Children 2009. 2008; UNICEF: New York.

- World Health Organization. World Health Report 2006: working together for health. 2006; WHO: Geneva.

- African Summit on HIV/AIDS, TB and other related infectious diseases. Abuja Declaration on HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and other related infectious diseases. Abuja, April 2001. At: <www.un.org/ga/aids/pdf/abuja_declaration.pdf. >. Accessed 14 February 2011.

- V Tangcharoensathien, W Patcharanarumol. Commentary: Global health initiatives: opportunities or challenges?. Health Policy and Planning. 25: 2010; 101–103.

- M Berer. Who has responsibility for health in a privatised health system?. Reproductive Health Matters. 18: 2010; 4–12.

- LO Gostin, M Heywood, G Ooms. National and global responsibilities for health [Editorial]. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 88: 2010; 719–719A.

- FM Waage, R Banerji, O Campbell. The Millennium Development Goals: a cross-sectoral analysis and principles for goal setting after 2015: Lancet and London International Development Centre Commission. Lancet. 376: 2010; 991–1023.

- World Health Organization. World Health Report 2006: working together for health. 2006; WHO: Geneva.

- World Bank. International development assistance at work: rebuilding Timor-Leste's health system. At: <http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL. >. Accessed 20 March 2011.

- M Mackintosh. Planning and market regulation: strengths, weaknesses and interactions in the provision of less inequitable and better quality care. Background paper for Commission on Social Determinants of Health. 2007; WHO: Geneva.

- V Tangcharoensathien, S Limwattananon, W Patcharanarumol. Regulation of health service delivery in the private sector: challenges and opportunities. 2008; International Health Policy Program, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand: Nonthaburi.

- G Lagomarsino, D de Ferranti, A Pablos-Mendez. Public stewardship of mixed health systems. Lancet. 374: 2009; 1577–1578.

- Governance matters 2008: Worldwide Governance Indicators 1996–2007. 2008; World Bank: Washington, DC.

- United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2007/2008: fighting climate change: human solidarity in a divided world. 2008; UNDP: New York.