Abstract

The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were defined in 2001, making poverty the central focus of the global political agenda. In response to MDG targets for health, new funding instruments called Global Health Initiatives were set up to target specific diseases, with an emphasis on “quick win” interventions, in order to show improvements by 2015. In 2005 the UN Millennium Project defined quick wins as simple, proven interventions with “very high potential short-term impact that can be immediately implemented”, in contrast to “other interventions which are more complicated and will take a decade of effort or have delayed benefits”. Although the terminology has evolved from “quick wins” to “quick impact initiatives” and then to “high impact interventions”, the short-termism of the approach remains. This paper examines the merits and limitations of MDG indicators for assessing progress and their relationship to quick impact interventions. It then assesses specific health interventions through both the lens of time and their integration into health care services, and examines the role of health systems strengthening in support of the MDGs. We argue that fast-track interventions promoted by donors and Global Health Initiatives need to be complemented by mid- and long-term strategies, cutting across specific health problems. Implementing the MDGs is more than a process of “money changing hands”. Combating poverty needs a radical overhaul of the partnership between rich and poor countries and between rich and poor people within countries.

Résumé

Les objectifs du Millénaire pour le développement (OMD), définis en 2001, ont placé la pauvreté au centre des préoccupations politiques mondiales. En réponse aux OMD de la santé, de nouveaux instruments de financement, appelés initiatives de santé mondiale, ont été créés pour cibler des maladies spécifiques avec des interventions à « gains rapides », afin d'obtenir des améliorations d'ici 2015. En 2005, le Projet Objectifs du Millénaire des Nations Unies a décrit les gains rapides comme des interventions simples et éprouvées avec « un impact potentiel très élevé à court terme et pouvant être appliquées immédiatement », contrairement à « d'autres interventions plus compliquées, qui demanderont dix ans d'efforts ou auront des bienfaits différés ». La terminologie a évolué de « gains rapides » à « initiatives à impact rapide », puis « interventions à fort impact », mais la nature à court terme de l'approche demeure. Cet article examine les mérites et les limites des indicateurs des OMD pour évaluer les progrès et leur lien avec les interventions à impact rapide. Il évalue ensuite des interventions de santé dans la perspective des délais et de leur intégration dans les services de santé, et analyse le rôle du renforcement des systèmes de santé à l'appui des OMD. Nous estimons qu'il faut compléter les interventions à court terme prônées par les donateurs et les initiatives de santé mondiale avec des stratégies à moyen et long terme qui dépasseront les problèmes spécifiques de santé. La réalisation des OMD est davantage qu'un « transfert de fonds ». La lutte contre la pauvreté requiert une refonte radicale du partenariat entre pays riches et pauvres, et entre riches et pauvres à l'intérieur des pays.

Resumen

Los Objetivos de Desarrollo del Milenio (ODM) definidos en 2001, centraron la agenda política mundial en la pobreza. En respuesta a los ODM en salud, se establecieron nuevos mecanismos de financiamiento, llamados Iniciativas Sanitarias Mundiales dirigidas a enfermedades específicas, con énfasis en intervenciones que produzcan resultados positivos rápidos, a fin de mostrar mejoras para el 2015. En 2005 el Proyecto del Milenio de las Naciones Unidas definió resultados positivos rápidos como intervenciones sencillas comprobadas con “un potencial muy alto de impacto a corto plazo que se puede implementar inmediatamente”, a diferencia de “otras intervenciones que son más complicadas y requerirán una década de esfuerzos o tendrán beneficios atrasados”. Aunque la terminología ha evolucionado de “resultados positivos rápidos” a “iniciativas de rápido impacto” y luego a “intervenciones de gran impacto”, aún continúa siendo un enfoque de corto plazo. En este artículo se examinan los méritos y las limitaciones de los indicadores de los ODM para evaluar los avances y su relación con las intervenciones de rápido impacto. Se evalúan determinadas intervenciones en salud a lo largo del tiempo y su integración en los servicios de salud; además, se examina el rol de fortalecer los sistemas de salud para apoyar los ODM. Se arguye que las intervenciones que están en la “vía rápida”, promovidas por donantes, y las Iniciativas Sanitarias Mundiales deben ser complementadas por estrategias de medio y largo plazo, que abarquen diversos problemas de salud. Realizar los ODM es más que una “transferencia de fondos”. La lucha contra la pobreza requiere una revisión radical de las alianzas entre los países ricos y los pobres y entre ricos y pobres en esos países.

In September 2000, the United Nations (UN) focused the attention of world leaders on the fight against poverty: 189 countries in the General Assembly expressed their commitment in the Millennium Declaration.Citation1 As follow-up to the Millennium Declaration, the Report of the Secretary-General was compiled, based on consultations among members of the UN secretariat and representatives of the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The commitment of the 2000 Millennium Summit was translated in 2001 into eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), under which there were 18 targets that should be reached by 2015 and 48 indicators related to those targets.Citation2 Although they were signatories to the MDG framework, the involvement of developing countries in this process was limited,Citation3 and only 22% of the world's national parliaments formally discussed the MDGs.Citation4

Health was recognized as a key determinant of human development in three MDGs that are directly related to health and three others that are more indirectly related. MDGs 4 and 5 focus on children and women respectively as priority target groups, and MDG6 focuses on HIV/AIDS, malaria and other major diseases, representing the bulk of the disease burden in low-income countries. MDG1 targets poverty and hunger, and includes an indicator that aims at reducing the number of underweight children. MDG7 focuses on environmental sustainability, with a target of halving by 2015 the proportion of people without sustainable access to safe drinking water. And finally, MDG8, promoting global partnership for development, includes a target of access to affordable essential drugs in developing countries.Citation2

Some important omissions in the MDG framework were later added: several new targets were added arising from the 2005 World Summit, including “achieving universal access to reproductive health” under MDG5 on maternal health.Citation5Citation6 This target was added as a result of efforts by UNFPA and a large constituency of NGOs working in family planning and reproductive health to reverse its exclusion during the original negotiation of the MDGs. Apart from being important in itself, ensuring access to sexual and reproductive health is instrumentally important for achieving many of the other MDGs.Citation5 In the 2010 review, health system strengthening was recognised as key to reaching the MDGs.Citation7Citation8

Initially, it was thought that the way to achieve the MDGs was mainly through resource mobilization to scale up the delivery of the 18 priority targets, and that the indicators would be used to measure the extent to which the targets were being reached.Citation9 To achieve the health-related goals, it was assumed that an increased share in national health budgets, as well as a larger share of bilateral and multilateral aid dedicated to health, would suffice. New global funding instruments, currently called Global Health Initiatives (GHIs), were launched,Citation10 mainly to support disease control programmes focused on prevention and treatment of the priority diseases.Citation11–13

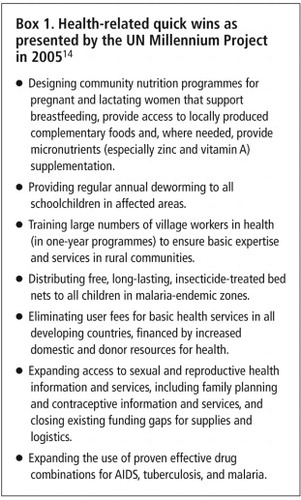

At a practical level, the agencies involved were in favour of short-term, “quick wins”, that is, interventions with “very high potential short-term impact that can be immediately implemented”. The UN Millennium Project presented these interventions as “simple and proven strategies” in contrast to “other interventions which are more complicated and will take a decade of effort or have delayed benefits”.Citation5Citation14 It was thought that donors would be less interested in complex interventions which would take ten or more years to produce measurable changes (e.g. in the status of women), and that quick wins were more likely to convince donors to invest. The term “quick wins” was later replaced by the term “quick impact” interventions but the basic concept was unchanged.Citation5Citation14 This concept became a buzzword in MDG discourse. However, the list of “quick win” interventions related to the health MDGs (Box 1

), presented in 2005 by the UN Millennium Project, were clearly not all simple and proven strategies.These proposed interventions range from relatively simple, inexpensive interventions (distribution of anti-malarial insecticide-treated nets) to complex and expensive ones (expanding access to sexual and reproductive health information and services), and are supported by more or less evidence (less in the case of micronutrient supplementation for pregnant women). They also mix health interventions with health care delivery strategies. The abolition of user fees, for instance, is a delivery strategy, not a health intervention. Moreover, the impact of each intervention depends on which aspects of the intervention are included, the level of care provided (community, outreach, campaigns, health centres and/or hospitals) and the skills of the professionals providing them.

Quick impact interventions are usually based on the availability of a cost-effective technology, often medicines, and the ability of their promoters to attract the attention of public and private donors to support their scaling-up at global level.Citation15 Quick wins (and simple packages) have successfully attracted a significant proportion of international and philanthropic funding for global health and seem to have successfully expanded the overall pool of development assistance for health over the past decade.Citation16Citation17 But many of these initiatives have been developed parallel to, not integrated into, the health care system in countries. Parallel approaches have been shown to lead to duplication (e.g. running parallel systems for delivering medicines), distortion (e.g. creating a separate cadre of better paid health workers for a specific programme), and disruptions (e.g. uncoordinated training programmes taking staff away from their jobs).Citation12Citation13Citation18 For example, in Burkina Faso, almost ten immunization campaigns per year were organized in 2009 and 2010, each of them taking roughly ten days of work and largely drawing resources (human resources, vehicles) from general health services – with detrimental consequences for ongoing care.Citation19 Similarly, in Mali, mass drug distribution to control and eliminate trachoma, schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis, as well as vitamin A distribution campaigns, are carried out several times a year. Yet a study in 2006, in the rural district of Douentza in Mali, showed that each nurse in charge of a health centre had been absent from their health centre for 45–47 working days to participate in campaign-related activities.Citation20

Input from other influential international actors from both outside and inside the UN system has added to the complexity, making it even harder for Ministries of Health to decide which interventions they should pursue. For example, the 2003–2006 Lancet series on Child and Maternal SurvivalCitation21Citation22 produced a list of effective interventions that could be delivered as single interventions or as a package. Then, in 2009 UNICEF, UNFPA, the World Bank, the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health and UNAIDS proposed a list of “high impact interventions” based on three essential criteria: (1) potential contribution to reduce the overall burden of maternal, newborn and child deaths, malnutrition and communicable diseases, (2) existence of a solid evidence base for their effectiveness, (3) costs and feasibility of achieving highly equitable, effective coverage.Citation19 Using these criteria, countries were encouraged to choose a list of high impact interventions to implement as priorities.Citation23 A phased approach with three scenarios suggested that countries should start by implementing and scaling up a minimum package. For Africa, a first phase (2009–2011) was proposed in the Strategic Framework for AfricaCitation24: to “jumpstart at scale” and strengthen those interventions with the highest impact on MDGs 4, 5 and 6 at the lowest cost, by delivering them through family outreach services and primary health clinics.

At the global level, the importance of health systems strengthening, and of addressing the underlying social determinants of health to achieve long-term sustainable progress, had also been gaining prominence in the first decade of the 21st century.Citation7 A tension was thus created between the political importance of showing measurable progress (so as to attract continued funding) and the importance of multisectoral action to achieve sustainable, long-term results, e.g. the importance of educating girls in order to reduce fertility and bring down maternal mortality. Yet with only a few years left before 2015, when the MDG targets are supposed to be achieved, belief in donor-centric quick impact interventions, funded with unprecedented amounts of money, continues unabated to have an influence. This is exemplified by the headline following the Global MDG Review meeting in September 2010 – that US$40 billion had been secured for women's and children's health,Citation25 minus any concrete plan for where or how it should be spent.

This paper examines the effects of the MDGs from the perspective of sub-Saharan African countries, many of whom have made some progress but are not on track to achieve the health MDGs by 2015.Citation26Citation27 These and other low-income countries are labelled as “lagging behind” and struggling to implement quick impact initiatives as the 2015 deadline looms.

What lessons can be learnt from past action so that the synergies between short- and long-term perspectives and goals can be harnessed? In answering this question, we examine the merits and limitations of the health MDG targets and indicators for assessing progress, analyse the effects of “quick impact” interventions in two case histories from West Africa, and look at how the different health MDGs have responded to quick impact interventions. We then assess specific health interventions through both the lens of time and their integration into health care services, and examine the role of health systems strengthening in support of the MDGs.

Merits and limitations of the health MDG targets and indicators in assessing progress

The MDGs represent an important tool for advocacy and political mobilization to fight poverty at global, national and regional levels. They have been a useful driver for improved data collection and hence for showing progress, or the lack of it, in key areas of development. However, the way in which progress is supposed to be measured using the 48 indicators has led to controversies about statistics and how they are constructed.Citation28

First, the MDGs are global targets, based on global trends from 1990 to 2015, rather than trends in a particular country or region. Sound, national target setting requires adaptation and cannot be attained with the automatic adoption of global targets. However, the way the targets have been conceived – as global targets – makes it impractical to transpose them straightforwardly to most sub-Saharan countries and has created unwarranted grounds for disappointment in Africa's progress. While some countries, the “MDG plus” countries (Thailand, Viet Nam and Chile) have set more ambitious national targets than the agreed global targets, very few African countries – such as Mozambique, Mali and Malawi – have adapted the MDGs to fit their own contexts, which would have meant setting targets below the agreed global ones.Citation29

Second, the MDGs are relative benchmarks, that is, most targets are expressed in relative terms – reducing under-five mortality by two-thirds and cutting maternal mortality by three-quarters. Reducing the under-five mortality rate from 10 to 5 per 1,000 live births implies a 50% reduction in deaths whereas lowering it from 250 to 200 leads to only a 20% reduction – yet the 20% reduction is ten times larger in absolute terms. Although some African countries show encouraging progress in absolute numbers, the use of relative targets does not reflect this sufficiently. Sierra Leone, Mozambique and Guinea, for example, reduced their national under-5 mortality rate by about 90 points between 1990 and 2009. Yet, this commendable achievement in absolute terms translates into a relative decline of about 35% – far below the target of a two-thirds reduction.Citation30 Instead of expressing it in terms of relative reduction or even as a reduction in absolute numbers, it would have been more appropriate to consider the country's performance in terms of accelerated progress over time, driven by immunisation rates, anti-malaria bednets distributed and improvements in basic health care. Liberia, Niger, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Uganda and Malawi all saw substantial acceleration in child survival rates after 1990; yet all are ranked among the countries that are off-track according to the global target of reducing under-5 mortality by two-thirds.Citation30–32

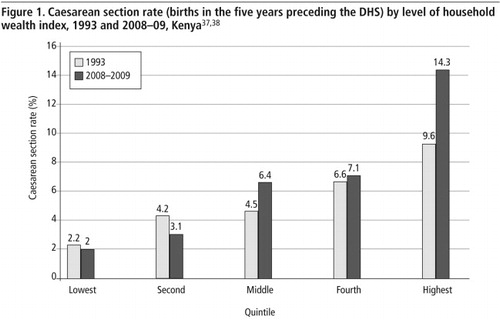

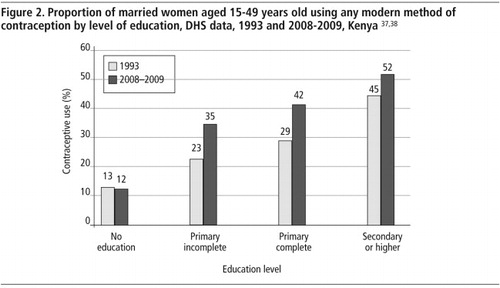

Third, if the indicators measured are expressed only as national averages, and the data are not disaggregated for different parts of a country or by socioeconomic status, they will fail to catch any inequities because they represent only the national average. However, progress towards achieving the health MDGs may not necessarily benefit the poorest, whose access to health and health care may actually worsen.Citation33 Evidence shows that most countries are making progress, but that few are managing to achieve inclusive and equitable progress. Instead, most of the gains are taking place among the top socioeconomic quintiles, while the lower quintiles are seeing little or no progress.Citation34–36 For Kenya, for example, using access to caesarean section as a proxy for access to emergency obstetric care, a comparison of disaggregated data from the 1993 and 2008–09 Kenya Demographic Health SurveysCitation37Citation38 shows overall improvement at national level, but reduced access among the two lowest quintiles. In 1993, the caesarean section rate was four times higher for the highest quintile compared to the lowest quintile, but it was seven times higher in 2008–09 (

). Similarly, as regards the coverage of family planning by level of education, women with no education had less access to a modern method in 2008–09 than in 1993 ( ). In addition, the rural-urban gap remains wide in most countries, with progress being considerably faster in cities than in villages.Citation35Hence, policy design should ensure that the underprivileged significantly benefit from interventions, and to monitor this, collected data should be disaggregated by socio-economic status and other equity-adjusted parameters. Achieving equity may also require a focus on the needs of different communities in a country, based on the particular race, ethnic, geographic, linguistic and/or gender dimensions of inequity historically.Citation3

Examples of the effects of “quick impact” interventions in West Africa

• Abolition of user fees for deliveries and caesarean sections

In recent years, one of the solutions proposed by governments and donors to improve access to health care in low-income countries has been abolition of or exemption from user fees. Targeted abolition of user fees started in early 2000 in West Africa for treatment of specific diseases (HIV, malaria, tuberculosis) and for vulnerable groups (pregnant women,Footnote* children under five). These policies were sometimes initiated too quickly, due to international pressure, as conditionality for accessing funds or loans (World Bank, IMF).Citation39

In the race to reach the Millennium Development Goals by 2015, the abolition of user fees for emergency obstetric care was included as a quick impact intervention with the aim of increasing the use of maternal health services. Mali began in 2005, Burkina Faso in 2006 and Benin in 2009. In Mali, an assessment by USAID of uptake of caesarean sections after the abolition of user fees, published in 2011,Citation40 showed that geographical barriers were still a problem, i.e. distance to a facility and cost and availability of transport, and that the gap in uptake between rich and poor was still present despite the new policy. In Burkina Faso, there was a 26.2 point increase from 44.5% to 70.7% in skilled attendance at delivery at health district level following the introduction of a national subsidy covering 80% of the direct costs of all deliveries (vaginal deliveries and caesarean sections), but in many places women were asked to pay more than the 20% left to the patient.Citation41–43 In Benin, similarly, the situational analysis of the FEM Health project,Footnote* aimed at evaluating the effects of user fee exemptions, revealed that some referral hospitals routinely asked women who have had a caesarean section to pay a top-up fee, to supplement the allocation from the State.

Several policies have been the subject of presidential promises at election time and had to be up and running within a short period of time. Technical staff in the Ministries of Health concerned had to implement these promises without any guarantee that the funding required would be available from the budget, which then created real problems at the point of implementation. This was the case in Guinea (Conakry), where targeted abolition of user fees was recently brought in, despite a lack of financial resources to implement the policy.Citation44

Abolition of user fees for deliveries and caesarean sections, though presented as a quick impact intervention, is actually a very complicated strategy to implement. Success is dependent on good prior estimates of financial and other resources needed, taking into account an increase in the patient load, and especially a willingness to enforce the policy by frontline staff, to ensure good implementation. These assumptions may be far from the reality in countries where there is a lack of skilled health professionals, wages are very low, and where strikes by civil servants against the decline in purchasing power are increasing.Citation45Citation46 Similarly, policies that exempt certain patients (e.g. those who are indigent) from paying are very difficult to achieve unless the exemption criteria are clear and applied correctly. Both sorts of policies need good coordination between the Ministry and local health authorities, since funds need to be transferred to ensure costs are covered in a timely manner.Citation39Citation47

• The effects on hospital budgets and quality of care in Burkina Faso

Even though more emphasis is being put on health systems and social determinants of health since the Report of the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health,Citation48 the model of quick impact interventions (intervention à gain rapide in French) is still active in sub-Saharan Africa, and even seems to have been emphasised in recent years. In Burkina Faso, a 2009 Ministry of Health guideline about implementing quick impact interventionsCitation49 states that the decision to implement these interventions was taken in 2008 and would be applied for the first time in the 2010 health districts' annual action plan. Despite new insights regarding the importance of health system strengthening at the 2010 MDG High Level Meeting in New York,Citation25 it is hard to imagine that this approach would be abandoned.Footnote* The initiatives listed in the guideline were:

| • | integrated management of childhood illness | ||||

| • | impregnated mosquito nets | ||||

| • | intermittent prophylactic treatment of malaria | ||||

| • | minimum package of activities in nutrition (prevention and treatment) | ||||

| • | immunization | ||||

| • | emergency obstetric and neonatal care, including an 80% exemption of user fees for caesarean sections, obstetric complications and neonatal intensive care. | ||||

| • | prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) | ||||

| • | family planning | ||||

| • | integrated management of diseases in the context of HIV | ||||

| • | second generation surveillance for HIV and STIs | ||||

| • | DOTS for tuberculosis | ||||

| • | development of a national blood transfusion programme.Citation49 | ||||

Since 2010, each health district of Burkina Faso has had to track these quick impact interventions and their corresponding budgets in their annual action plan. In the urban health district of Bogodogo in Ouagadougou (615,000 inhabitants), the funds to implement these quick impact interventions (around €950,000 for one year) represented 78% of the total 2010 discretionary budget of the district. The head of the operating theatre and the head of the obstetrics & gynaecology department of Bogodogo district hospital (performing 800 caesarean sections a year) are facing major difficulties with the replacement and ordering of equipment, including items that are essential for ensuring quality of care and not very expensive, such as products for the sterilization of instruments, indicators that sterilization has been completed at the right temperature, new scissors and replacements for obsolete operating instruments. They say it has become more and more difficult to work because of this. When the hospital manager was asked when this equipment would arrive, the reply was: “They are not for quick impact interventions, so it is not a priority for the district."

The managerial team also complained that although the 80% exemption for user fees for caesarean sections was funded under the quick impact funding and promoted by the government, the costs for equipment and maintenance for doing caesareans and other surgery were not being taken into account, leading to deterioration of the operating theatre premises and equipment. Indeed, the hospital also experienced a shortage of anaesthetics, absence of sterile gowns and towels due to the breakdown of the sterilizer, which forced staff to evacuate emergency obstetric cases to the teaching hospital (Personal experience, co-author Fabienne Richard).

The three health MDGs have not benefited equally from quick impact interventions

MDG6 offers most scope for “quick wins” (e.g. the distribution of insecticide-treated nets and antiretroviral treatment), and not surprisingly it has been the health MDG that has received most attention from Global Health Initiatives. A UNAIDS June 2011 report states that about 6.6 million people were receiving antiretroviral therapy in low- and middle-income countries at the end of 2010, a nearly 22-fold increase since 2001.Citation50 And nearly 290 million insecticide-treated bednets were delivered to sub-Saharan African countries by manufacturers during 2007–2010 and were available for use. The largest absolute fall in malaria deaths was in Africa, where 11 countries have reduced malaria cases and deaths by over 50%.Citation27

MDG4 is also showing some improvements, mainly in the widescale implementation of a few quick impact interventions for malaria, HIV control and measles immunization that have cut deaths in children under the age of five from 12.5 million in 1990 to 8.1 million in 2009. However, reductions in neonatal mortality, which are dependent on good antenatal care, skilled attendance at delivery and post-partum care, have not been achieved through the Expanded Program on Immunization, as they are not amenable to single, quick impact interventions.

MDG5 has responded least to single and short-term interventions. Less than half of pregnant women give birth with a skilled attendant in many parts of the developing world.Citation25 Cutting maternal mortality ratios and rates requires a functioning health system that provides access to both skilled birth attendants and emergency obstetric care. Lack of education, low status and socio-economic status, rural habitation and living in a conflict/crisis situation are all very much linked with this MDG.

Access to family planning, an MDG5 indicator, could be considered a quick impact intervention (an efficient way to reduce unintended and unwanted pregnancies and thus maternal mortality, with the possibility of outreach activities at community level). It can also contribute to reducing the total fertility rate and population growth, affecting consumption and climate change. However, in contrast with HIV programmes, funding for family planning programmes has decreased over the past decade.Citation5

In addition, lack of effective global leadership for MDG5 has led to the fragmentation of interventions.Citation5 There are many initiatives, such as by the Global Campaign for the Health MDGs; WHO Department of Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health; UN Secretary General's Global Strategy for Women's and Children's Health; the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health; Women Deliver's Countdown to 2015; the US President's Global Health Initiative (incorporating family planning and reproductive health, plus AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis and more);Footnote* Norwegian Prime Minister's Initiative for MDGs 4 & 5; and many more. But it is not always clear where responsibility lies, who is doing what or even what is being funded or where, let alone how effective it has been.

It is not only MDG5 that needs to go beyond quick wins. It is also the case for MDGs 4 and 6, which also require a broader approach to make further progress. The Millennium Development Goal Report 2010 acknowledged the progress made with respect to bednets and insecticide spraying in reducing the spread of malaria, but noted there has been limited success in expanding the treatment of malaria with the more effective artemisinin-based combination therapy.Citation8 Already in 2004, Josh Ruxin, assistant professor of public health at Columbia University, compared the first wave of people receiving HIV antiretroviral treatment to “low-hanging fruits”, but noted: “You quickly reach a point where you can't treat more people unless you develop the national health systems”. Citation51 Although success in scaling up HIV treatment has shown this scepticism not to be entirely warranted, the distortion potential of disease-specific programmes that run in parallel to health systems, of which HIV treatment is a prime example, continues to be the subject of a lively debate.Citation13Citation16Citation52

Examining quick impact interventions through the lens of time and integration in health care services

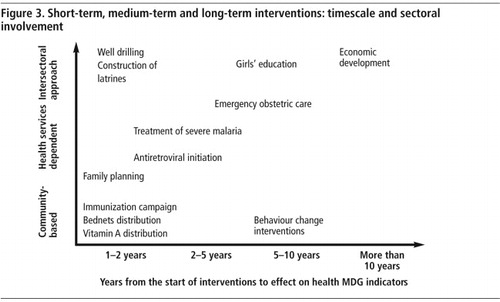

To contextualise the wish for quick impacts, health-related interventions can yield short-term, medium-term and/or long-term results.Citation53 They can also be evaluated according to the extent of their integration into and dependence on health services and systems, ranging from community-based interventions to ones needing multisectoral approaches beyond the Ministry of Health ( gives several examples).

Interventions that yield short-term results tend to be simple to implement over a short period of time, but more complex interventions with a potentially high impact in the short term can also be included. Simple interventions can be compared to quick win interventions – effective and relatively easy to implement – either because they are not labour-intensive (or require a large number of staff but over a very short period of time). They usually consist of standardised interventions and are logistics-intensive, such as measles vaccination to reduce child mortality.Citation22 These sorts of interventions can be delivered at the community level and reach a high level of coverage quickly. Global Health Initiatives tend to favour these interventions as they can yield measurable results in a very short time period, one that is compatible with funding cycles and a project approach. Antiretroviral treatment is a good example of an intervention with quick short-term gains but that must be sustained over the long-term and requires a more complex implementation approach.

Interventions that yield results in the medium term require more time and more effort before tangible impacts can be observed. They require qualified health workers and a larger list of specific inputs like medicines or equipment that should be available on a 24-hour basis. Good management skills at the local level of the health system are also required. Emergency obstetric care, which requires well-functioning around-the-clock services and a well-functioning system of referral up the health system pyramid, is a good example of a medium-term intervention. It could have a major impact on the health MDGs but only if an adequate mix of inputs comes together in the right way. The 2010 report by the Women Deliver Countdown to 2015 for Maternal, Newborn and Child Survival documented that interventions that are delivered in fixed health facilities (e.g. delivery and post-partum/post-natal care) tend to show greater disparities between rich and poor than preventive activities delivered free at the community level (e.g. vaccinations, vitamin A supplementation, insecticide-treated nets).Citation54 Footnote*

Interventions that generate long-term results require an intersectoral approach on a broad scale. Girls' education and economic development are good examples. They require long time frames for tangible impacts, that mostly occur in the “next generation”,Citation48 though short- and medium-term positive results from community engagement and health promotion (e.g. hand washing with soap, use of latrines, low-cost well drilling) can also be seen. A recent WHO expert group points out that “much of the improvement in health has occurred in areas that are not usually considered to be within the health sector”.Citation55 Thus, effects on health should be taken into account in all relevant public policies, and a three-pronged approach (short-term, medium-term and long-term) is needed to reach and sustain the health-related goals.

illustrates this approach from an intervention perspective but it could also apply to a health workforce perspective (from the quick gain activities of task-shifting to the long-term investment in training skilled professionals) or to a health care financing perspective (from the short-term strategy of abolishing user fees for targeted services to the long-term creation of a national health insurance system). For all these areas short-, medium- and long-term strategies will need to be combined. From an equity perspective, these strategies can either be implemented in a way that ensures the easiest results (by reaching those already accessing services), or in a way that ensures that the most vulnerable groups benefit as well.

We fear that the sense of urgency driving the MDG targets carries the risk that too much of the available resources will be allocated to quick impact interventions without sufficient investment in interventions and systems necessary to achieve medium- and long-term results.

Health systems strengthening: a window of opportunity

In 2009, the WHO Maximising Positive Synergies Collaborative Group on the impact of Global Health Initiatives on national health systems highlighted the fact that there is no single solution for improving national health systems. It requires an intersectoral, coordinated approach. Nor is there one blueprint or a standard list of actions which work in all countries. Solutions are not only technical but human, and need to be contextualised. They are also managerial (especially human resources management) and involve governance and accountability issues at multiple levels.Citation46Citation56 The involvement of civil society and a focus on vulnerable groups are important to ensure equitable access. Innovative solutions have to be found, taking into account the particular context. Publicly provided health services have been complemented by a multitude of other providers who have to be taken into consideration, i.e. private for-profit and not-for-profit providers, social franchises, social marketing, community agents and others.Citation13

As the Global Health Initiatives bump up against the constraints of a limited health work force and fragile health systems, they increasingly encourage applicants to include interventions to strengthen the health system in their proposals. Previously, such activities had to fit within disease-specific proposals. 2010 saw the launch of the Health Systems Funding Platform which brings together the Global Fund, the World Bank, and the GAVI Alliance, with facilitation from WHO, to allow countries to use new and existing funds more effectively for health systems development and to help them access donor funds in a manner that is aligned to their own national processes.Citation57 A pilot project was planned to be launched in 2011 in four or five low-income countries, to use the national health plan as the basis for funding requests. Results have still to be shown at a time when the Global Fund to Prevent AIDS, TB and Malaria has received lower than expected replenishments and WHO is facing a major institutional challenge.Citation58 WHO has had to reduce its expenses to cover a deficit of about US$300 million in 2010, which was done through a drastic reduction in staff by one-third. They were also asked by their Executive Board to redefine WHO’s role and responsibilities in the context of the increased influence of Global Health Initiatives.Footnote*

Conclusion

Since 2000, donors have largely supported selective quick win/impact approaches to health development which have allowed the picking of several “low-hanging fruits” in many settings. While there is room for improvement with regard to these interventions, further progress will depend largely on developing medium-term and long-term strategies that pay more attention to the development of health systems, a condition for significant progress in maternal and reproductive health, but also for future progress in child health and reductions in HIV infection, tuberculosis and malaria. MDGs 2 and 3 (ensure education for all and promote gender equality and empowerment of woman) are key to maternal and child health and tend to be omitted in discussions on how the targets are to be met.Citation59 Finally, progress towards achieving the MDGs should not happen at the expense of continued efforts to improve the social determinants of health.

Some African countries show that change is possible: that it is possible to move from a selected, free services policy to a national health insurance system, as in Ghana;Citation60 to combine community-based and facility-based approaches, as in Ethiopia, and increase the number of community health workers while training more qualified health centre staff;Citation61 and to coordinate donors to support a national health plan, as in Rwanda.Citation62 These three countries have in common the strong leadership of their presidents and ministries and the political will to move beyond “quick wins”.Citation63Citation64

We urge leaders to make sure that medium- and long-term investments are underway, even if the results may not be tangible by 2015. Comprehensive assessments of health development show that investments in health systems and in social determinants pay off.Citation65Citation66 Global Health Initiatives, being the biggest funders of the MDGs, should adapt their strategies and broaden their time horizons and ambitions by aiming to achieve health for all. Implementing the MDGs is more than a process of “money changing hands”.Citation29 A radical overhaul of the partnership between rich and poor countries, and between rich and poor people within countries, is needed.

Acknowledgements

We thank Wim Van Damme, Vincent de Brouwere and Monique Van Dormael, of the Department of Public Health, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, for their comments on an earlier draft of this article. The Institute of Tropical Medicine in Antwerp has a Framework Agreement (FA3) with the Belgian Directorate-General for Development (DGD) and received funding for this work.

Notes

* The free policies implemented first were preventive activities like antenatal care and were followed more recently by caesarean sections and normal deliveries.

* See: <www.abdn.ac.uk/femhealth/>. August 2011.

* In Nigeria, as well, “quick wins” were still on the agenda during the presidential election campaign. See <www.thenigerianvoice.com/nvnews/30032/1/mdgs-quick-win-as-campaign-tools-for-2011-election.html>. June 2010.

* See: <www.kff.org/globalhealth/upload/8160.pdf>. March 2011.

* These three interventions are often mentioned in this paper because they are the typical quick impact interventions promoted and supported by Global Health Initiatives and donors.

* See WHO reform for a healthy future. 2011. At: <www.who.int/dg/reform/en/index.html>.

References

- United Nations. United Nations Millennium Declaration. Resolution adopted by the UN General Assembly. A/RES/55/2. 2000; UN: New York.

- United Nations. Road map towards the implementation of the United Nations Millenium Declaration. UN General Assembly. A/56/326. 2001; UN: New York.

- J Waage, R Banerji, O Campbell. The Millennium Development Goals: a cross-sectoral analysis and principles for goal setting after 2015. Lancet. 376(9745): 2010; 991–1023.

- UN Development Group. Making the MDGs matter: the country response. 2005; UN Development Group: New York.

- UN Millennium Project. Public Choices, Private Decisions: Sexual and Reproductive Health and the Millennium Development Goals. 2006; Earthscan: London. At: <http://www.unmillenniumproject.org/documents/MP_Sexual_Health_screen-final.pdf. >. Accessed 30 July 2011.

- United Nations. The Millennium Developement Goal Report 2005. 2005; UN: New York. At: <http://www.un.org/summit2005/MDGBook.pdf. >. Accessed 30 July 2011.

- J Sundewall, RC Swanson, A Betigeri. Health-systems strengthening: current and future activities. Lancet. 377(9773): 2011; 1222–1223.

- United Nations. The Millenium Developement Goal Report 2010. 2010; UN: New York. At: <http://unstats.un.org/unsd/mdg/Resources/Static/Products/Progress2010/MDG_Report_2010_En_low%20res.pdf. >. Accessed 26 April 2011.

- Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. Macroeconomics and Health/ Investing in Health for Economic Development. 2001; WHO: Geneva.

- R Brugha, G Walt. A global health fund: a leap of faith?. BMJ. 323(7305): 2001; 152–154.

- RG Biesma, R Brugha, A Harmer. The effects of global health initiatives on country health systems: a review of the evidence from HIV/AIDS control. Health Policy and Planning. 24(4): 2009; 239–252.

- P Travis, S Bennett, A Haines. Overcoming health systems constraints to achieve the Millennium Development Goals. Lancet. 364(9437): 2004; 900–906.

- World Health Organization Maximizing Positive Synergies Collaborative Group. An assessment of interactions between global health initiatives and country health systems. Lancet. 373(9681): 2009; 2137–2169.

- UN Millenium Project. Investing in development. A practical plan to achieve the Millenium Development Goals. Overview. 2005; Communications Developement Inc: Washington DC. At: <www.unmillenniumproject.org/documents/MainReportComplete-lowres.pdf. >. Accessed 26 April 2011.

- J Shiffman. A social explanation for the rise and fall of global health issues. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 87(8): 2009; 608–613.

- G Ooms, R Hammonds, C Decoster. Global health: what it has been so far, what it should be, and what it could become. C Decoster, B Marchal, W Soors. Working Paper Series of the Studies in Health Services Organisation and Policy. 2011; ITG Press: Antwerp.

- G Yamey. Scaling up global health interventions: a proposed framework for success. PLoS Medicine. 8(6): 2011; e1001049.

- B Marchal, A Cavalli, G Kegels. Global health actors claim to support health system strengthening: is this reality or rhetoric?. PLoS Medicine. 6(4): 2009; e1000059.

- G Boussery, V Campos da Silvera, B Criel. Community of practice on the service delivery study high impact interventions. Harmonization for Health in Africa. 2011; Institute of Tropical Medicine: Antwerp.

- Y Coulibaly, A Cavalli, DM Van. Programme activities: a major burden for district health systems?. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 13(12): 2008; 1430–1432.

- OM Campbell, WJ Graham. Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: getting on with what works. Lancet. 368(9543): 2006; 1284–1299.

- G Jones, RW Steketee, RE Black. How many child deaths can we prevent this year?. Lancet. 362(9377): 2003; 65–71.

- M Chopra, E Daviaud, R Pattinson. Saving the lives of South Africa's mothers, babies, and children: can the health system deliver?. Lancet. 374(9692): 2009; 835–846.

- UNICEF World Bank UNFPA PNMCH UNAIDS. A Strategic Framework and Investment Case for Reaching the Health Related Millennium Development Goals in Africa by Strenghtening Primary Health Care Systems for Outcomes. 2009; UNICEF: New York.

- United Nations. Keeping the promise: united to achieve the Millenium Development Goals. UN General Assembly. A/65/L.1. 2010; UN: New York.

- CJ Murray, J Frenk, T Evans. The Global Campaign for the Health MDGs: challenges, opportunities, and the imperative of shared learning. Lancet. 370(9592): 2007; 1018–1020.

- United Nations. The Millenium Developement Goal Report 2011. 2011; UN: New York. At: <www.un.org/millenniumgoals/11_MDG%20Report_EN.pdf. >. Accessed 30 July 2011.

- J Vandemoortele. Is Africa missing the target or are you missing the point? Presentation at IOB, University of Antwerpen, Debating development series, 10 December 2008. At: <www.ua.ac.be/main.aspx?c=.IOB&n=70225. >. Accessed 26 April 2011.

- J Vandemoortele. Making sense of the MDGs. Development. 51: 2008; 220–227.

- UNICEF. Trends in under-five mortality rates 1960–2009. At: <www.childinfo.org/mortality_ufmrcountrydata.php. >. Accessed 30 August 2011.

- ZA Bhutta, M Chopra, H Axelson. Countdown to 2015 decade report (2000–10): taking stock of maternal, newborn, and child survival. Lancet. 375(9730): 2010; 2032–2044.

- S Fukuda-Parr, J Greenstein. How should MDG implementation be measured: faster progress or meeting targets?. 2010; International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth: Brasilia, 1–26.

- E Zere, P Tumusiime, O Walker. Inequities in utilization of maternal health interventions in Namibia: implications for progress towards MDG 5 targets. International Journal Equity in Health. 9: 2010; 16.

- DR Gwatkin, A Bhuiya, CG Victora. Making health systems more equitable. Lancet. 364(9441): 2004; 1273–1280.

- Overseas Development Institute. MDG Report Card: Measuring Progress Across Countries. 2011; ODI Publications: London.

- J Vandemoortele, E Delamonica. Taking the MDGs beyond 2015. IDS Bulletin. 41(1): 2010

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics ICF Macro. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2008–09. 2010; KNBS and ICF Macro: Calverton, MD.

- National Council for Population and Development. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 1993. 1994; NCPD, CBS, and MI: Calverton, MD.

- B Meessen, D Hercot, M Noirhomme. Removing user fees in the health sector in low-income countries: a multi-country review. 2009; UNICEF: New York.

- M El-Khoury, T Gandaho, A Arur. Improving Access to Life-saving Maternal Health Services: The Effects of Removing User Fees for Caesareans in Mali. Health Systems 20/20, editors. 2011; Abt Associates Inc: Bethesda, MD.

- Amnesty International. Giving Birth, Risking Death: Maternal Mortality in Burkina Faso. 2009; Amnesty International: London.

- Ministère de la Santé. Tableau de bord santé 2009. Direction générale de l'information et des statistiques sanitaires, editor. 2010; Ministère de la Santé du Burkina Faso: Ouagadougou.

- Ridde V, Richard F, Bicaba A, et al. The national subsidy for deliveries and emergency obstetric care in Burkina Faso. Health Policy and Planning 2011. (In press)

- Guinée Direct. Santé: Gratuité de la césarienne en Guinée, entre mythes et réalités. 27 Mai 2011. At: <www.guineedirect.info/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=2135%3Asante-gratuite-de-la-cesarienne-en-guinee-entre-mythes-et-realites&catid=293%3Apolitique&Itemid=400. >. Accessed 28 July 2011.

- N Gerein, A Green, S Pearson. The implications of shortages of health professionals for maternal health in sub-saharan Africa. Reproductive Health Matters. 14(27): 2006; 40–50.

- LS Thomas, R Jina, KS Tint. Making systems work: the hard part of improving maternal health services in South Africa. Reproductive Health Matters. 15(30): 2007; 38–49.

- F Richard, S Witter, V De Brouwere. Innovative approaches to reducing financial barriers to obstetric care in low-income countries. American Journal of Public Health. 100(10): 2010; 1845–1852.

- Commission on the Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. 2008; WHO: Geneva.

- Ministère de la Santé. Guide national de mise en oeuvre intégrée des interventions à gain rapide. 2009; Ministère de la Santé du Burkina Faso: Ouagadougou.

- UNAIDS. AIDS at 30, Nations at the crossroads. 2011; UNAIDS: Geneva.

- D Sontag. Early test for US on its gobal fight on AIDS. New York Times. 14 July 2004. At: <www.nytimes.com/2004/07/14/world/early-tests-for-us-in-its-global-fight-on-aids.html. >. Accessed 26 April 2011.

- DW Van, M Pirard, Y Assefa. How can disease control programs contribute to health systems strengthening in sub-Saharan Africa?. C Decoster, B Marchal, W Soors. Working Paper Series of the Studies in Health Services Organisation and Policy. 2011; ITG Press: Antwerp.

- J Rohde, S Cousens, M Chopra. 30 years after Alma-Ata: has primary health care worked in countries?. Lancet. 372(9642): 2008; 950–961.

- World Health Organization, UNICEF. Countdown to 2015 Decade Report (2000-2010): taking stock of maternal, newborn and child survival. 2010; WHO, UNICEF: Washington, DC.

- World Health Organization. Research and development coordination and financing: report of the expert working group. 2010; WHO: Geneva. At: <www.who.int/phi/documents/RDFinancingwithISBN.pdf. >. Accessed 30 July 2011.

- L Penn-Kekana, B McPake. Improving maternal health: getting what works to happen. Reproductive Health Matters. 15(30): 2007; 28–37.

- Aidspan. Global Fund board approves two health systems funding platform projects. 4-5-2010. At: <www.aidspan.org/index.php?issue=122&article=6. >. Accessed 26 April 2011.

- PS Hill, P Vermeiren, K Miti. The Health Systems Funding Platform: is this where we thought we were going?. Global Health. 7: 2011; 16.

- Gender equity is the key to maternal and child health [Editorial]. Lancet. 375: 2010; 1939.

- National Health Insurance Authority. The road to Ghana's health care financing. 2011.

- G Ooms. The new dichotomy in health systems strengthening and the role of global health initiatives: what can we learn from Ethiopia?. Journal of Public Health Policy. 31: 2010; 100–109.

- R Hayman. Milking the Cow: Negotiating Ownership of Aid and Policy in Rwanda. Global Economic Governance Working Paper 2007/26. 2007; University College: Oxford. At: <www.globaleconomicgovernance.org/wp-content/uploads/hayman_rwanda_2007-261.pdf. >. Accessed 30 July 2011.

- J Donnelly. Ethiopia gears up for more major health reforms. Lancet. 377(9781): 2011; 1907–1908.

- R Wisman, J Heller, P Clark. A blueprint for country-driven development. Lancet. 377(9781): 2011; 1902–1903.

- ZA Bhutta, S Ali, S Cousens. Alma-Ata: rebirth and revision. 6 interventions to address maternal, newborn, and child survival: what difference can integrated primary health care strategies make?. Lancet. 72(9642): 2008; 972–989.

- J Riley. Low income, social growth, and good health. 2008; University of California Press: Berkeley.