Abstract

This article offers a theory-of-change framework for social justice advocacy. It describes broad outcome categories against which activists, donors and evaluators can assess progress (or lack thereof) in an ongoing manner: changes in organisational capacity, base of support, alliances, data and analysis from a social justice perspective, problem definition and potential policy options, visibility, public norms, and population level impacts. Using these for evaluation enables activists and donors to learn from and rethink their strategies as the political context and/or actors change over time. The paper presents a case study comparing factors that facilitated reproductive rights policy wins during the transition from apartheid to democracy in South Africa and factors that undermined their implementation in the post-apartheid period. It argues that after legal and policy victories had been won, failure to maintain strong organizations and continually rethink strategies contributed to the loss of government focus on and resources for implementation of new policies. By implication, evaluating effectiveness only by an actual policy change does not allow for ongoing learning to ensure appropriate strategies. It also fails to recognise that a policy win can be overturned and needs vigilant monitoring and advocacy for implementation. This means that funding and organising advocacy should seldom be undertaken as a short-term proposition. It also suggests that the building and maintenance of organisational and leadership capacity is as important as any other of the outcome categories in enabling success.

Résumé

Cet article propose un cadre pour la théorie du changement dans le plaidoyer en faveur de la justice sociale. Il décrit de vastes catégories de résultats selon lesquelles les activistes, les donateurs et les évaluateurs peuvent jauger de manière suivie les progrès (ou le manque de progrès) : les changements des capacités d'organisation, la base de soutien, les alliances, les données et les analyses dans une perspective de justice sociale, la définition des problèmes et les options politiques potentielles, la visibilité, les normes publiques et les impacts au niveau de la population. En utilisant ces critères pour l'évaluation, les activistes et les donateurs peuvent tirer des enseignements et revoir leurs stratégies pour suivre l'évolution du contexte politique et/ou des acteurs. L'article présente une étude de cas comparant des facteurs qui ont facilité des gains politiques pour les droits génésiques pendant la transition de l'apartheid à la démocratie en Afrique du Sud et des facteurs qui ont miné leur application à la fin de l'apartheid. Il avance qu'après les victoires juridiques et politiques, l'incapacité à conserver des organisations fortes et à repenser en permanence les stratégies a contribué à une perte de la priorité gouvernementale et des ressources accordées à l'application de politiques nouvelles. Par conséquent, l'évaluation de l'efficacité uniquement par un changement politique réel ne permet pas un apprentissage constant pour assurer des stratégies adaptées. Elle ne tient pas non plus compte du risque de perte des gains politiques qui requiert d'être vigilant dans le plaidoyer et le suivi de la mise en łuvre. Il en découle que le financement et l'organisation du plaidoyer doivent rarement être des activités à court terme. L'article suggère aussi que l'instauration et l'entretien de la capacité organisationnelle et du leadership sont aussi importants que toute autre catégorie de résultat pour parvenir au succès.

Resumen

En este artículo se ofrece un marco de teoría de cambio para abogar por la justicia social. Se describen categorías generales de resultados mediante los cuales activistas, donantes y evaluadores pueden evaluar los avances (o falta de estos) de manera continua: cambios en la capacidad organizacional, base de apoyo, alianzas, datos y análisis desde la perspectiva de justicia social, definición del problema y posibles opciones de políticas, visibilidad, normas públicas e impactos en los niveles de población. Al utilizar estos resultados para la evaluación, los activistas y donantes pueden aprender de sus estrategias y reformularlas según vayan cambiando los actores y/o el contexto político. Se expone un estudio de caso en el cual se comparan los factores que facilitaron las victorias de políticas a favor de los derechos reproductivos durante la transición del apartheid a la democracia en Sudáfrica y los factores que debilitaron su implementación en el período post-apartheid. Se argumenta que, tras las victorias legislativas y políticas, el no mantener organizaciones sólidas y reformular las estrategias continuamente contribuyó a la pérdida de enfoque del gobierno en la aplicación de nuevas políticas y en los recursos para éstas. Implícitamente, evaluar la eficacia exclusivamente mediante un cambio de política no permite el aprendizaje continuo para garantizar estrategias adecuadas. Además, no se reconoce que tras lograr determinada política, ésta puede ser revocada y que su implementación requiere monitoreo atento y esfuerzos de promoción y defensa (advocacy). Esto significa que el financiamiento y la coordinación de actividades de promoción y defensa rara vez se deben realizar como una propuesta de corto plazo. Indica también que el desarrollo y mantenimiento de la capacidad de organización y liderazgo es tan importante como cualquiera de las demás categorías de resultados para tener éxito.

At one of my interviews with the Ford Foundation for a job as a program officer in reproductive health and rights, I was asked whether I had any experience in successfully influencing policy change.

“Yes,” I said. “On abortion in South Africa.”

I proceeded to tell the story of the campaign to increase access to abortion and other reproductive health services in South Africa. The campaign culminated in the Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act 1996 and in significant, related policy changes that gave the public free access to primary health care, an increased range of contraceptives for free, the right to screening and treatment to prevent cervical cancer, and more.

The interviewers then asked whether I'd had experience of such advocacy going wrong.

“Yes,” I said. “On abortion in South Africa!”

And I described how, despite winning passage of a law that should have led (and did, to a limited extent) to a significant decrease in the number of maternal deaths and ill-health in the country, the campaign had not managed to address the major barriers to countrywide implementation.

This story highlights a number of the challenges to advocates, donors, and evaluators in understanding and advocating for social change. This article, therefore, aims to unravel some of the key components of policy advocacy as a way of reflecting on what kinds of outcomes can be used as markers of progress towards achieving the goals of social justice. Before considering the nature of policy advocacy, it is worth making explicit the values underlying my use of the term “social justice”, which draws on the analysis of Nancy FraserCitation1Citation2 and on principles of human rights.Citation3 Social justice advocacy describes efforts to: a) increase fairness in the distribution of resources;Footnote* b) end discrimination against all groups, fostering values that recognize all people as equal; and c) promote the participation of people in policy and implementation processes that affect their lives, and transparency and accountability for how decisions are made and how they impact on society.Footnote†

Theory of change for policy advocacy

There is a general consensus that advocacy and advocacy evaluation cannot be done without a theory of change (whether explicit or implicit) and that this needs to be grounded in social science researchCitation4 and in experience, in order to draw on field learning, without which it can be weak or problematic.Citation5 One has to understand what the organization, coalition or network thought it was doing and what it hoped to achieve by its actions in the short and medium term in order to be able to evaluate it. A number of evaluators use Kingdon'sCitation6 approach to policy analysis as the basis of a theory of change to explain the nature and complexity of policy processes.Citation7–10

Kingdon points out that there are a world of problems which never get onto the political agenda, and similarly a world of potential solutions. In tandem, “political events flow along on their own schedule and according to their own rules, whether or not they are related to problems or proposals”(p.20).Citation8 Hence, the process of problem identification, the process of developing solutions, and the political process are not sequential but should be understood as “multiple streams” that flow independently and simultaneously – and in each, different actors may take part.

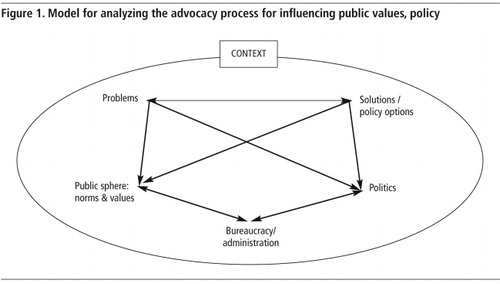

For this reason, it is necessary to analyse how a problem gains recognition as a problem to be addressed in the political terrain, how specific solutions get onto the political agenda, and why politicians are concerned with certain issues rather than others at a particular moment in time. I have added a fourth stream, that of bureaucracies and administration, since implementation is as much a site of policy making as is law; and bureaucrats and administrators, as with policy makers, act on the basis of personal and institutional concerns that may bear no relationship to the problems and desired solutions of those who are most in need or marginalized.Citation11 Hence, the focus of advocacy is on the processes required to influence problem definition and identify matching solutions and then to get these onto the agendas of the politicians, bureaucrats and other decision-makers who determine policies and their implementation, and keep them there in the face of opposition or bureaucratic apathy (see

).Kingdon suggests that “policy entrepreneurs” have the role of creating connections between these streams, working with the media and lobbyists as critical components of this process. In relation to social justice advocacy, I frame these as “policy activists”Citation12 to denote the link to social movements, and the recognition that mobilization of those most affected can in itself change the policy environment, in particular the public discourse, to get specific problems and preferred solutions onto public and policy agendas.

It is here that the question of values comes into play. Pastor and Ortiz specifically critique the process of “policy entrepreneurs” writing papers and engaging policy makers without engaging and generating grassroots leadership so that the social movement can “make sure to directly involve those with ‘skin in the game’ and make sure that the frames and values are derived from them and not from focus groups conducted by distant intermediaries”(p.2).Citation13 The choice of the term “policy activist” aims to signal the desirability, from a social justice point of view, of building the capacity of individuals and groups who are part of or closely tied to grassroots movements, to play this role – to get solutions onto the political agenda that match problems identified by those who are most marginalized or negatively affected by a policy. Thus to what extent potential beneficiaries of policy are active in advocacy and to what extent the content of resultant policy proposals reflects their perspectives, are both significant markers for evaluating social justice advocacy.

Donors, evaluators and, indeed, many advocates tend to focus on a policy win. But policy wins are usually the result of multiple strategies coupled with windows of opportunity that are very seldom predictable. In addition, the very same factors that influence policy wins need to be sustained in order to support policy implementation, to address challenges to policy, and to achieve the ultimate goals of advocacy campaigns.

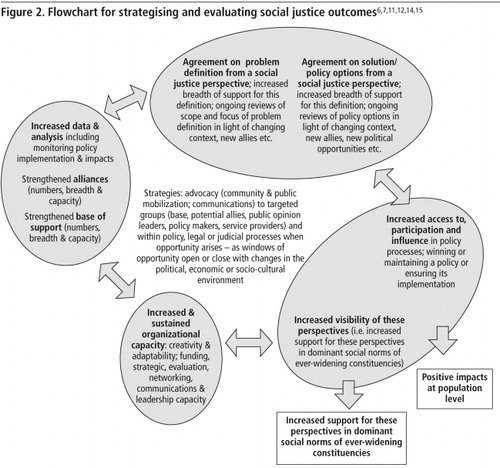

A theory-of-change framework of measurable outcomes, presented below, can be used by those who are supporting or undertaking social justice advocacy to reflect on whether the diverse factors that influence change are being addressed, and whether social justice values are being retained in the process. It encourages, in particular, reflection on whether the needs and aspirations of those who are most excluded in society remain at the forefront of advocacy campaigns. Without a theory of change – without clarity about what advocacy hopes to achieve and what strategies will be pursued to get there – it is not possible to assess progress and adjust strategies.

Measurable outcomes of policy advocacy

A number of reviews of the literature on successful advocacy initiatives group together the outcomes that advocacy campaigns tend to aim for.Citation7Citation14Citation15 Reisman et al call these groups “outcome categories”. The first four lay the groundwork for effective advocacy:

| • | strengthened organizational capacity, | ||||

| • | strengthened base of support, and | ||||

| • | strengthened alliances, which in turn draw on | ||||

| • | increased data and analysis from a social justice perspective. | ||||

These four outcomes form the basis for conducting advocacy, sometimes quietly within the corridors of power and sometimes from the outside, through the mobilization of constituencies, public actions, and the engagement of the media. They enable the following outcome, which is a marker of significant progress in advocacy:

| • | the development of consensus around a common definition of the problem and possible policy options by an ever-widening constituency of people (both of which will also evolve over time with new insights, data, and constituencies informing them). | ||||

These, in turn, form the basis for the advocacy movement as a whole, comprising individuals, organizations, and alliances that are continually adapting to changes in context, in order to ensure the “readiness” of their organizational capacity, messages, and strategies. They enable effective engagement in the policy process, which falls within the sixth outcome category:

| • | increased visibility of the issue in policy processes, resulting in positive policy outcomes, including maintaining gains, and maintaining pressure through ongoing monitoring of the implementation of policy. | ||||

Ultimate impacts, usually beyond the time frame of any grant or set of grants, would be:

| • | shifts in social norms, such as decreased discrimination against a specific group or increased belief that the state should provide high quality education. That said, along the way, one may start to see shifts in public understanding and visibility of the issues, as the problem definition or potential solutions gain social acceptance over time; and | ||||

| • | shifts in population-level impact indicators, such as decreased violence against women, fewer suicides among gay youth, or increased educational achievement among groups with historically poor achievement (see which draws on a range of sources). | ||||

What are the dynamics that influence outcomes in each category, and the kinds of outcomes donors, grantees, and evaluators may seek from a social justice values perspective? The case of reproductive rightsFootnote* advocacy in South Africa during the transition from apartheid to democracy and in the 15-year period thereafter – the “transition” and “post-apartheid” periods – provides a case study through which to explore these dynamics. The information is based on a range of policy analyses undertaken regarding the role of civil society in these periods,Citation12,16–19 including a recent review of the state of civil society advocacy on these issues, conducted by the author in collaboration with Khathatso Mokoetle.Citation20

The case of reproductive rights advocacy in South Africa: 1990–2010

From the mid- to late-1990s, donor support for mobilizing grassroots constituencies, undertaking policy-oriented research, and establishing policy advocacy NGOs and coalitions played a critical role in the achievement of wide-ranging sexual and reproductive rights policy changes during the era of transition from apartheid to democracy in South Africa. Many donors were not “reproductive rights” donors, but were more concerned with ending apartheid and building movements to enable development under apartheid and in the transition to democracy.

The mobilization of civil society, coupled with civil society leadership's entry into political power and government, enabled the achievement of a group of policies that are among the strongest in the world from both public health and human rights perspectives. The Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act 1996 allows a woman to choose to terminate a pregnancy within the first 12 weeks, or to do so in consultation with a medical practitioner between 13 and 20 weeks. It also allows midwives to conduct abortions and does not require minors to get parental consent before having an abortion. It enables the realization of a number of human rights for women, in particular the right to life, liberty, autonomy, and security of the person; to equality and nondiscrimination; to privacy; to the highest attainable standard of health (including sexual health); and the right to decide the number and spacing of their children. One result of the legislation was better training of midwives. In addition, the Department of Health established a National Committee for Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths, which publishes reports on maternal deaths to enable the providers of health care to review their guidelines for the management of common causes of death.Citation21 Together these initiatives led to a 90% reduction in abortion-related maternal mortality by 2001,Citation21 and a decline in the loss of dignity and autonomy associated with women's lack of access to safe abortions. It had a particularly strong impact on morbidity in young women.Citation22

Policies were made and judicial findings published on a range of other related issues during this time as well, including a replacement of the existing population control policy with a rights-based population policy,Citation23 guidelines for contraceptive provisionCitation24 and the introduction of a cervical screening programme.Citation25 By the late 1990s, organizing around the HIV/AIDS pandemic in the country also came into its own. Donor funding played a critical role in supporting the legal, research, and grassroots capacities needed to challenge a government in denial as well as international pricing regimes that made antiretroviral treatment for people in developing countries unaffordable. Successful advocacy, including litigation, ultimately resulted in national roll-out of testing and treatment programmes.Citation18

Yet, despite the fact that sexual and reproductive rights issues are central to effective prevention of HIV transmission, and that people living with HIV/AIDS face daily challenges regarding their sexual and reproductive decision-making, these issues have slowly shifted from centre stage during the transitional period to outside the public health agenda in the post-apartheid period. As a result, since 2003, there has been an increase in maternal deaths.Citation26 This is attributed to a number of factors, including hypertension, that could be prevented with stronger health service interventions and, most notably, deaths due to non-pregnancy-related infections, specifically HIV.Citation27–29 The situation has been exacerbated by a decline in access to abortions in the public sector – from 45% of community health centres providing services in 2008–09 to 25% in 2009–10, in part due to a shortage of nurses trained to perform first trimester terminations.Citation30 Even efforts in the post-apartheid period have ground to a halt. For example, guidelines for the introduction of medical abortion that were drafted in 2004 were only finalised in 2008, and at the time of writing only one province has officially implemented medical abortion.Citation31

Between 2002 and 2008, three of the leading sexual and reproductive rights organizations in the country – the Progressive Primary Health Care Network, the Women's Health Project and the Planned Parenthood Association closed down, and a fourth, the Reproductive Rights Alliance, closed its office and let its staff go.Footnote*

While the loss of these advocacy organizations does not explain the loss of service outreach within the public health system, it does partly explain why these failures were allowed to happen with impunity, and why issues of sexual and reproductive rights were not incorporated into the HIV/AIDS civil society and policy agendas. At moments of crisis, such as anti-abortion challenges to the abortion law at the Constitutional Court and in Parliament, ad hoc mobilisation by legal groups, individuals who were active in the original legal process, and international NGOs such as Ipas has managed to garner enough momentum to provide inputs to government, politicians, and legal advocacy organizations to keep the 1996 abortion law in place. But they have not managed to garner sufficient institutional, public or political momentum to take forward the achievements of the transition period.

In reviewing the outcome categories associated with advocacy processes, the factors that facilitated and constrained the achievement and implementation of reproductive rights policies during this period in South Africa are discussed by way of illustration.

Strengthened organizational capacity

Strong organizational capacity in non-profit organizations and coalitions is a pre-condition for successful social justice advocacy efforts.Citation32 Hence assessing improvements in organisational capacity over time is a key evaluation outcome category. Organizational capacity involves a number of essential components that donors, activists, and evaluators would assess: strategic and evaluation capacity with their associated leadership capacity and ability to generate new leaders; fundraising capacity, and financial management capacity; and networking and communications capacity.

Less easy to measure, but arguably most important, is the extent to which a leading organization in an advocacy campaign or coalition has “adaptive capacity”(p.135)Citation33 – the capacity to learn as the situation changes.Citation34–36 This requires an inclusive style of leadership that is able to take an organization and its coalition members through a process of reflection together.

In relation to the case study, three of the four reproductive rights organizations that closed in South Africa between 2002 and 2008 had lost the strategic leadership that had enabled them to make an impact in the transition period. None of them had managed to groom second generation leadership that would be able to adapt to the post-apartheid environment – in particular leadership of women living with HIV/AIDS, given the enormity of the challenges HIV poses for reproductive rights. In interviews with the leadership of the organizations that closed and with members of other donor-funded sexual and reproductive rights groups, while some argued that the problem had been a lack of funds, most recognized that the overriding factor was a lack of leadership, vision, and organizational capacity.Citation20

While major policy victories had been achieved and the new challenge was to enable and monitor implementation, organizations were not able to adjust to the changing environment, particularly in terms of rethinking their strategies.

Similarly, the reality of the HIV pandemic required reproductive rights organizations to reassess the terrain and redefine their demands to take account of HIV and AIDS. It also required them to shift their mode of engagement with donors and even to change donors. Many donors who were working to an anti-apartheid brief stopped funding in the country or, in the case of bilateral and multilateral donors, shifted their funds to government. New donors were coming in, but in the health field, a large proportion were concerned with addressing HIV as one of the country's biggest challenges and did not recognize the centrality of sexual and reproductive rights to preventing HIV.

The emergence and growth of many HIV organizations was indeed appropriate for this time, and critical in addressing the right to treatment for people living with HIV and AIDS. But allowing sexual and reproductive health and rights to fall off the agenda at the same time was a serious loss.

Strengthened base of support and alliances

The “base of support” for an issue refers to grassroots, leadership, and institutional support, which includes the breadth, depth, and influence of support among the general public, interest groups, and opinion leaders. The social justice values dimension of building a base of support pertains to the participation of those who are most affected in defining the problem and potential policy proposals or options for implementing policy. Here, effectiveness overlaps with values. While the participation of those most affected is a values-based principle of a social justice approach, it is also pragmatic because of the need to ensure appropriate policies and maintain the degree of mobilization necessary for policy victories and for holding governments accountable for implementation.

As an advocacy process gets under way, different organizations representing different interests and bringing in a wider range of insights, contacts, and relationships will almost certainly need to be mobilized.Citation8 However, this breadth of support also creates challenges. Alliances need to be nurtured. The larger a coalition, the wider the range of interests held within it. If new perspectives, new research findings and new experiences from the piloting of interventions are brought in by new allies, achieving consensus on the problem definition and possible policy options as part of the alliance-building process becomes more complicated. How much the agreed solutions continue to represent the interests of those most affected is an important question for evaluation, as the dilution of policy demands is a risk in the process of seeking consensus among ever wider sectors.

In the case study, the process of winning support for reproductive rights during the period of transition involved mobilizing a wide range of constituencies, including workers, doctors and nurses, women (including rural women), young people, lesbians, disabled people, faith-based organizations, and the structures of the newly legalized African National Congress, including its Women's League. These groups were drawn together by the Women's Health ProjectCitation17 in a process of deliberation about the reproductive and sexual health and rights problems facing women. Through interactions between experts (both academics and practitioners) and these organized constituencies, policy proposals were developed within months of the establishment of democracy in April 1994. These experts included many people who, during this period of deliberation, were elected into parliament or joined the new government administration. As a result, there was wide-ranging support for the issues, and many contentious issues had been debated and resolved before they ever got onto the official political agenda. Given the breadth of the base of support and the diversity of allies, a substantial negotiation of values was necessary. In the debates about the impact of unsafe and illegal abortions on women's health and lives, for example, the need for safe abortion became clear from a public health point of view and from the point of view of saving women's lives, because of high rates of death and illness caused by illegal abortions.Citation37Citation38

At the time, the overarching frame was the need to end discrimination on the basis of race. This provided a powerful motivation as, under the previous regime, only those with access to substantial resources – in effect, only white women – had access to safe abortions, whether legally or illegally. Thus, ending discrimination was the overriding value that enabled consensus. But beyond that, there were differences. The doctors involved in the deliberations argued strongly that only doctors should be able to do abortions, even though there is ample evidence in the clinical literature, including from South Africa, that trained midwives and nurses can carry out and manage safe abortions. This position was more a reflection of doctors' professional interests. In contrast, nurses and midwives participating in the process saw the opportunity of increasing their areas of responsibility and potential income. Women's rights groups recognized that the absence of doctors in rural areas would mean that rural and poor women would continue to have unsafe abortions. Thus, the final proposal, and the law that was ultimately passed, included allowing trained midwives to perform abortions, thereby increasing access for the poorest and most marginalized women.Citation39

This example illustrates how the process of building a base of support and alliances requires the negotiation of values. From a social justice perspective, it shows how the needs and rights of those on the margins need to take precedence, and organizations representing them need to hold more “mainstream” advocacy groups accountable.

By 2006, however, there was no longer any national organization or coalition systematically bringing together groups concerned with reproductive rights in this way. Reproductive rights organizations describe a situation in which competition between groups had become the norm, particularly in a context of scarcity of donor funds for this work.Citation20 Equally significantly, few of these organizations had retained or built formal and ongoing linkages with grassroots constituencies, such as HIV and AIDS organizations, let alone managed to mobilise them to express moral outrage at the dire state of women's reproductive health and how the HIV pandemic was exacerbating it. Reproductive rights networks in fact declined, as did their means of communication, such as shared newsletters. Also, many of those who had been employed in non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and research institutions focusing on reproductive rights were now working on HIV and AIDS, without taking sexual and reproductive rights concerns into those spaces.

The lack of attention to sexual and reproductive rights in the context of HIV required a major refocusing of attention by reproductive rights activists as to who needed to be drawn into a base of support and alliances for reproductive rights, in order to keep reproductive rights demands on the public and political agenda. The HIV terrain was itself fraught with conflict over strategies, particularly the balance of attention between prevention and treatment, and there was competition between groups.Citation40 This no doubt exacerbated the difficulty of reproductive rights groups in broadening their alliances.

One of the critical social justice values that supports the establishment and maintenance of alliances is collaboration, and this is an area where donor expectations can exacerbate a situation. Given the complexity of theories of change in relation to policy advocacy, no one organization should ever be expected or expect itself to deliver all of the outcomes, but rather that a mix of organizations would collectively work to achieve these. Collaboration between organizations in recognition that they each have something to contribute, rather than competition for attribution of victories, is not only a “good” value, but is what is needed to be effective. Effective advocacy puts learning and working together above competition. This is a challenge for advocacy groups, particularly in the context of competition for scarce donor resources.Footnote*

It also poses one of the biggest challenges to donors – how to create enough financial security for a group of organizations that they are willing and able to acknowledge and support each others' strengths, without fearing that their own contributions will be devalued. And above all, the social justice value of participation – the inclusion of all the relevant issues and the people who are most affected – is particularly important as the range of allies increases and strategic compromises are made. This holds true even if policy victories are won; organizations representing those at the margins need to establish sustained mechanisms for holding decision-makers – whether government, donors, or even national NGOs — accountable for their decisions.

Increased data and analysis from a social justice perspective

Evidence, whether in the form of research findings or personal testimonies, is frequently helpful and sometimes essential to strengthen the capacity of the base and allies to pin down the problem definition, to shape and test potential policy options, and to analyze a changing policy environment. Hence, to what extent information and analysis are available and used to inform advocacy is a question for assessing the development of an advocacy strategy. Both the media and policymakers may feel that research findings legitimize policy demands. Producing data and analysis may also carry a significant values dimension to the extent that it provides information on previously ignored groups or is produced by and carries the perspectives of such groups. Moreover, the orientation and perspective of researchers influences what questions they ask and how they interpret their findings. So research should be generated by or in close relationship with those who are the target of policies, to ensure accurate information on which to shape policy options.

A strategy that donors can use here is enabling advocacy groups to commission the necessary research so that the findings are more likely to be used. On the other hand, gathering data beyond those needed immediately for advocacy can be essential for gaining deeper insights into problems, policy options, and indeed the nature of the policy terrain. Research may need to be done over some months or even years, and therefore cannot be commissioned at the moment the findings are needed. Advocacy NGOs and membership-based organizations also need to be identifying research questions and allying with research entities in order to get research done. Evaluating the information dimension of advocacy requires not only looking at its source, but also its effectiveness in advocacy.Citation41 The lack of linkages between researchers and research findings with groups able to use research for advocacy is usually the result of a poor theory of change, such as the assumption that researchers have an interest in their findings being used to promote change, or the assumption by researchers that new evidence will inevitably lead to improved policy outcomes.Citation42 As a result, researchers often fail to put an effort into building the necessary linkages with a base of support and allies on the issues.

In South Africa in the transition period, advocates put substantial energy into identifying and forming alliances with researchers with key knowledge. For example, a historian was able to give evidence in Parliament about the long history of abortion among all ethnicities in the country, so that it could not be construed as “un-African”. Also, reproductive health researchers anticipated the need for health systems data that would inform politicians about the costs of unsafe abortion to the public health system, and produced it before the issue went to Parliament. Advocates also gathered key anecdotal evidence, for example, from religious women whose clergy had supported them in having abortions, thus undermining the view that abortion was necessarily “anti-Christian”. Legal experts studied international law to formulate arguments about constitutionality and legal interpretation. All of this helped to frame messages for the media and in policy debates in ways that kept the issues of discrimination against women and public health at the forefront. This illustrates the tight relationship that was developed between researchers and activists as well as the strategic nature of research. In addition, a number of research institutions, sometimes in collaboration with reproductive rights NGOs, developed and evaluated methods for building health service and community support for reproductive rights and particularly for abortion.Citation43Citation44

In contrast, some of the gaps identified in the post-apartheid period are the lack of connection between activists and researchers, and the lack of a forum for identifying research priorities and sharing research findings as the basis of reproductive rights advocacy.Citation20 As a result, there is no mechanism for bringing new research findings into NGO and community activism. There has also been extremely limited mobilization to get government and civil society groups to use the tested methods developed of building community and health worker support for implementing the reproductive rights policies described above.Footnote* There has been one initiative, conducted under the auspices of a project to develop treatment guidelines for HIV-positive women, which ran an e-list that fostered debate on reproductive rights issues as they pertain to HIV/AIDS and established a collaborative project with researchers, clinicians, and some activists to develop guidelines on specific topics. But it, too, has faltered, as the host organization expressed discomfort with the “movement-building” and advocacy dimensions of the project, wanting to run it as a more dispassionate research project.

This disconnect – between those who see research as closely linked with advocacy and mobilization and those keen to keep research politically neutral – is a common problem faced by advocates and a reason why advocacy theories of change need to include it as an outcome area worthy of continual monitoring.Citation45Citation46

Increased support for a specific problem definition and policy options

This takes me back to the values dimension of research for advocacy. Allan, McAdam and Pellow talk about the need for a “motivational frame” that will persuade people to take action, making them want to get involved.Citation47 This is where research findings are reframed to support campaign language. Activists frame issues for their base of support and allies and try to get their frame, or perspective, taken up by the media and those in a position to influence public attitudes and government policy.Citation48 Increased standardization in the articulation of the problem and potential policy options is a marker of the coalescing of a base of support and alliances, particularly as numbers grow. In the search for early indicators of effective advocacy, the ability to cohere a growing group of people who recognize a problem, and then come to agreement around a specific problem definition that is drawn from and talks to the experience of those most affected, is key. It brings together the efforts in the previous outcome categories and is therefore a solid indicator of movement towards the goal(s). Monitoring how a problem definition and policy options are renegotiated as new allies are found or as the political, social, or economic context changes, and the extent to which they remain true to the concerns of those suffering the greatest discrimination or lack of access to resources, is core to the maintenance of a social justice perspective in evaluation. Changes in the degree of support for the activists' problem definition or policy option by policy thinktanks or other groups with resources and power that activists have targeted, are an indicator of the effectiveness of their advocacy.

As noted in South Africa during the transition period, reproductive rights activists were slow in recognising and responding to the scope of the HIV crisis.Citation49 HIV activists were having to cope with stigma, deaths of leaders and a government in denial. Leadership of the HIV movement was predominantly by men whose perspectives on HIV struggles were influenced by the early framing of HIV in the US,Citation48 which gave little attention to the dynamics of heterosexual sexual relationships in fostering HIV transmission. In South Africa in 2001, reproductive rights activists and lawyers decided to work in alliance with HIV/AIDS activists and lawyers to ensure that potential litigation for the implementation of programmes to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV would be framed around women's reproductive rights, including the right to have healthy babies. But over time the lawyers let go of this frame in favour of arguments based on the right to health care, and particularly to HIV treatment.Citation16 In general, AIDS activists' dominant claim was for the right to treatment, which “constructed women as bearers of children, and as patients, rather than as active agents in their own right”.Citation16 At times women were blamed for the escalation of HIV and in general the focus on preventing mother-to-child transmission failed to acknowledge the breaches in sexual and reproductive rights that made women particularly vulnerable,Citation50 a phenomenon not particular to South Africa.Citation51 The leading HIV organizations – the Treatment Action Campaign – was successful in mobilising activities that brought media attention and creating a “moral consensus” regarding the right to treatment.Citation40 In the context of AIDS denialism, much of the media focus was on the conflict between the government and HIV activists,Citation48Citation52 with very little attention to the lived realities of people living with HIV, nor to the high levels of sexual violence,Citation53 and cultural imperatives to have children, all of which were key determinants in the escalation of HIV. Claims regarding the need to promote sexual and reproductive rights as a key dimension to preventing HIV brought a level of complexity that this call could not contain, or, argued differently, neither AIDS activists nor reproductive rights activists were able to frame these issues in ways that caught the public and media imagination. Hence, a critical opportunity for broadening and deepening public understanding and legal precedent regarding the scope of reproductive rights and women's rights in particular, was lost. In the process, public and policy recognition of the right to treatment eclipsed the issues underlying the HIV/AIDS epidemic, in particular the lack of mutuality in sexual and reproductive relationships.

There was information, there were researchers, but there was no frame around which to build a collective understanding and set of demands. In the post-apartheid era and in the context of the pandemic, a new frame is needed. In the recent assessment of the state of reproductive rights organizing in South Africa,Citation20 what became clear was that there is no longer a shared problem definition among remaining reproductive rights advocates. Each interviewee had a somewhat different focus: the absence of attention to men, the absence of attention to sexual orientation, the absence of lesbians' voices among those concerned with sexual orientation, the absence of attention to young people's interests, the absence of attention to women living with HIV, and so on.Citation20 At this writing a new initiative is underway to bring these together under a broader frame, in recognition that mutually respectful sexual and reproductive relationships and the ability of all people to make decisions about their sexual and reproductive lives are fundamental to achieving equality for all people and to effectively preventing HIV and AIDS.Footnote*

Struggles around meaning, around what aspects of an issue are most pressing and should have priority in policy demands, are common. What the media chooses to cover brings further complexity. For this reason, tracing shifts in problem definition and policy options, and the extent to which they garner increased support by diverse constituencies, is a helpful indicator for activists and donors to assess progress.

Increased visibility of the issue in policy processes resulting in positive policy outcomes

The issue of “readiness” is particularly important in policy advocacy because the actual moments for policy change often come and go as political and economic contexts change. It is much easier for policy activists to move their agenda when there are changes in context that create windows of opportunity,Citation9 for example in the run-up to elections or after the election of a new party or president. Windows can also be created through activismCitation54 – mobilizing public concern about an issue, or using litigation to force state action, as occurred in South Africa in the struggle for AIDS treatment.Citation18 This is why solid and coordinated strategies among groups and coalitions aiming for change are so important. Windows of opportunity are critical moments for policy activists seeking to push a transformative agenda, compared to “politics as usual”, where they may only be able to push for small improvements to existing policy. Shaw describes the need for “tactical activism”,Citation55 where policy advocates use a window of opportunity by finding a way to link their solution to a problem that is on the political agenda. Such tactical activism assumes advocacy groups are already prepared so that they can take advantage of any such windows.

Winning the right of civil society to participate in certain policy forums is a critical outcome in itself. Achieving representation or participation specifically of marginalized groups in those forums, is an additional critical outcome. Once the right to participation has been won, a quality outcome would be the ability of these participants to be heard in these forums. Groups will frequently claim participation as an achievement, which it is. But the more important question is whether the groups' participation has been of a quality that it is being taken seriously by other stakeholders, whatever their position on the topic, and, whether it is influencing the debate, and ultimately, whether it has “strengthened the accountability of state institutions to civil society groups”(p.51).Citation56

In South Africa, the high degree of access of civil society reproductive rights groups to policymakers during the transition period was a key factor in the movement's success. And in the post-apartheid period, one of the victories of the HIV/AIDS movement has been the right to participation. The South African National AIDS Council (SANAC) comprises sectors where groups representing diverse interests – women, youth, men, people living with HIV/AIDS – can advocate for their issues and participate in negotiations and debates with government about policy and its implementation. There is no similar forum for reproductive health and rights. But, given the prevalence of HIV/AIDS, SANAC is an essential forum for bringing reproductive rights issues to the fore. Yet the existing sector groups have not brought it into the debate. The women's sector – which is one where one might expect to see reproductive rights issues raised – has been noticeably disorganized and silent on these issues, reflecting the lack of organizational capacity, base, allies, and shared message.

Beyond evaluating readiness, donors, advocates, and evaluators would also need to assess if and how the policy message gains traction in a policy agenda and policy debate, and whether increased numbers of policymakers show an interest in and ultimately take up a social justice perspective on the issue. Ultimately, they would be looking to see this perspective being adopted, funded and implemented, with effective mechanisms for monitoring implementation. Note that a positive policy outcome may not be a new policy but “maintaining the status quo”, where an existing policy that supports the advocacy coalition's values has been under threat.Citation14Citation57 It is also worth monitoring unexpected victories and how these came about. Once a policy is won, ongoing reflection on the theory of change would be needed to assess the extent to which advocacy is effectively targeted to ensure that the new policy is resourced to ensure equity in implementation. Policy advocates have to continue to watch the political process, because policies can not only fail through lack of implementation but can also be overturned at any time. This is why grantmaking to influence policy has to assume long-term planning and commitment.

Shift in social norms

In the long term, to sustain policy victories, one needs to build public support for an issue. Hence, the identification of shifts in social norms is a key indicator of long-term impact. In the early stages of an advocacy process, evaluation might assess this outcome in terms of greater visibility of a social justice perspective on the policy issue. As the campaign strengthens, building public outcry over an issue can be a means for policy activists to create a window of opportunity where politicians are pushed to take up a policy issue. But despite the conventional wisdom that public communication strategies are essential to successful advocacy, visibility alone is not a determinant of policy success. Public opinion may or may not be amenable to change through media influence.Citation58Citation59 Indeed, sometimes the visibility of a highly provocative issue can make it harder to maneuver it into a policy process, because visibility serves to mobilize the opposition – as is frequently the case in relation to abortion. In addition, one sometimes achieves social justice policy victories without majority support of the public; hence, there is no causal predictability between opening public debate and winning policy change, let alone implementation. Where dominant social norms are not in support of an issue, policy activists may decide not to engage the public at large. Advocates need to ensure that in developing their theory of change for a specific advocacy goal, they interrogate whether engaging the public through media and other public spaces would be a help or hindrance in creating a conducive policy environment for the desired change.

In South Africa, the change in the abortion law in 1996 was won in the context of an overarching frame of ending discrimination and its resultant impacts on women's health and lives. A number of doctors who were also anti-apartheid activists took positions of power in the first democratic government – the Minister of Health, the head of the Health Portfolio Committee in Parliament, and the head of Maternal Health in the Department of Health. In addition, reproductive rights organizations had mobilised grassroots organizations around this issue and won the support of their leadership.Citation17 However, despite the prevalence of abortion across all religious and cultural traditions in the country, it is a silent phenomenon and causes disquiet when brought into the public sphere. Women who know about the availability of free abortions, and can afford transport to the few facilities providing them, make use of them. Organizing such women and the public in general to speak out about the lack of services is quite another challenge. Reproductive rights activists recognised the need to build public and bureaucratic support, and most particularly support of health care providers. They developed and tested interventions to build community understanding of reproductive rights, ways of preventing pregnancy, and the limited role of abortion within that, such as Communities for Choice, Citation43 and values clarification.Citation60 These proved effective. But, neither these nor subsequent activists managed to implement these interventions on a wide scale, nor to persuade government to do so. They have similarly made very limited inroads in building support among nurses and midwives, and here, too, well-tested interventions locally and internationally, such as Stepping Stones, Citation61 Health Workers for Change Citation62 and values clarificationCitation63 have not been institutionalized. In particular, the idea of the right of people to choose whether or not to have children is a critical frame for the issues, and it has not been won. As a result, one irony of the new abortion law is that nurses often put pressure on women living with HIV to have abortions or to be sterilized after giving birth, not out of support for women's right to make reproductive choices, but as a result of the stigma of HIV and AIDS. The failure of government to implement is itself a product of dominant social norms. Only when there have been strong advocates within government has implementation been strengthened.Citation31

This illustrates the complexity of the challenge of developing an effective frame within which to promote reproductive rights in this context, and the broader point that shifting public norms is a particularly context-specific challenge.

Changes in impact

This final outcome category refers to the hoped-for impacts of policy change on the lives of the population and the conditions under which people are living.Citation15 From a social justice point of view, one would be looking for declines in discrimination against and stigmatization of specific groups of people, increases in equity of distribution of resources across the population as a whole, e.g. in access to health care, and the institutionalization of mechanisms for participation in policymaking and monitoring. Most important would be sustaining these improvements over time.

The South Africa case serves to reinforce the importance of maintaining an eye on advocacy goals over the long run and remaining vigilant, even after policy-level victories, to keep on strengthening the work in each of the outcome categories so that impacts are monitored over time, and strategies to maintain and improve these are re-oriented if and when contexts change.

Conclusion

While policy change itself is easy to monitor, the complexity and unpredictability of implementing policy change raises questions about how to plan and strategize for such changes, and how to monitor whether any progress is being made. The theory of change presented in this article offers donors, advocacy organizations, and evaluators a way of conceptualizing the process of change and a range of outcomes that can be assessed in an ongoing way. They need to monitor whether existing organizational development, mobilisation of a base and allies and advocacy strategies are ensuring that organizations are able to effectively shift public opinion and ready to engage policymakers and implementers about a problem and potential policy or implementation options as opportunities arise. Hence the focus of both strategic planning and evaluation is on the “steps that lay the groundwork”,Citation8 shifting the policy environment, and thus contributing to the achievement of policy change and implementation. Monitoring of impacts, too – whether shifts in social norms or in population-level indicators – while frequently too distant to measure within the time-frame of annual grants, or even five- or ten-year periods, can be helpful in identifying where policy victories do not appear to be resulting in effective implementation.

The primary lesson illustrated by the South Africa case study is that social justice goals are frequently complex and require long-term investment and ongoing evaluation. In South Africa, demands to address AIDS treatment took over public and political space in ways that ignored the importance of sexual and reproductive rights in their own right and in preventing the spread of HIV. This drew attention away from these issues despite the slew of new laws that required implementation to protect public health. Would a more reflective process along the way have prevented these losses? From the perspective of donors, evaluators, and, above all, those hoping to revitalize this movement, there are critical lessons in relation to all of the outcome categories. Most particularly, the failure of the reproductive rights movement to rethink its theory of change as the context changed provides lessons for social justice advocates in many contexts.

The approach to policy advocacy described in this article is in contrast with the traditional view of policy processes as linear.Citation64 Rather, it recognizes that those engaged in policy advocacy processes – whether as donors, advocates, or evaluators – need to monitor changes in capacity in all outcome categories and create a continuing process of analysis and learning for the advocacy initiative, assessing the appropriateness of the theory of change in relation to changes in the political and organizational context. If the only focus of evaluation were the policy outcome, there would be no reason for assessing readiness, and, given that a policy victory may take years, even decades to achieve, and yet more to implement, the work along the way would be devalued – just as the need for ongoing post-policy advocacy would be forgotten. Moreover, failure to recognize the complexity of social change, particularly with highly contested issues, allows donors to imagine that short-term grant making should deliver and sustain policy victories – something for which there is no evidence. The base and allies need to be sustained, renewed and expanded over time, problem definitions and policy or implementation options continually re-assessed, messages reshaped, and advocacy sustained. In addition, the perspectives, interests, participation and agency of those most affected by the issue have to be kept at the heart of these processes.

Acknowledgements

This paper was originally published in the Foundation Review 2011;2(3):94–107 and is reprinted here with their kind permission. The Foundation Review retains the copyright. This is a revised and updated version. I was Director of the Women's Health Project from 1991 to 2000. I want to thank the Ford Foundation for giving me two months' study leave in 2009, during which I investigated these issues. I would also like to thank Marion Stevens for providing helpful input on an earlier version of the paper, and Gail Andrews and Stefanie Röhrs for their extremely helpful comments on this version.

Notes

* For example, in relation to services such as health or education, ensure equity in their availability, accessibility, acceptability and quality.

† Hence the term “social justice” is used broadly to incorporate social, economic, cultural, civil and political rights.

* In the South African context, the language of “reproductive rights” is used to describe the rights to accessible, affordable, appropriate, and quality health services; to information; to autonomy in sexual and reproductive decision-making; and to freedom from discrimination, coercion, and violence as they relate to reproduction. These rights are undermined by poverty as well as by discrimination on the basis of gender, race or ethnicity, sexual orientation, disability, and other bases of discrimination.Citation24

* These were not the only groups advocating for sexual and reproductive rights and health, but were key national voices with a strong rights orientation and sophisticated strategies that mobilised diverse constituencies in support of these rights. Significantly, in the post-apartheid period more international NGOs established themselves in South Africa, predominantly focusing on strengthening service provision rather than on advocacy.

* That said, there are times when groups have fundamental differences in their goals and strategies, and a donor requirement for collaboration could be equally problematic.

* The NGO Ipas has made some headway in training public health services in parts of some provinces.

* The review of civil society perspectives referred to earlierCitation20 has resulted in a decision to establish a new organizations called the Sexual Health and Rights Initiative – South Africa (SHARISA) to help reframe the issues and mobilise diverse constituencies around an analysis of the connections between diverse struggles pertaining to sexual and reproductive rights, including HIV.

References

- N Fraser. Justice Interruptus: Critical Reflections on the “Postsocialist” Condition. 1997; Routledge: New York.

- N Fraser. Social Justice in the Knowledge Society: Redistribution, Recognition, and Participation. Beitrag Zum Kongress “Gut zu Wissen.” Heinrich-Boll-Stiftung. 26 October 2006. At: <http://wissensgesellschaft.org/themen/orientierung/socialjustice.pdf. >. Accessed 17 August 2009.

- S Gruskin, L Ferguson. Using indicators to determine the contribution of human rights to public health efforts: Why? What? and How?. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 87: 2009; 714–719.

- C Christie, M Alkin. The user-oriented evaluator's role in formulating a program theory: using a theory- driven approach. American Journal of Evaluation. 24: 2003; 3.

- A Mackinnon, N Amott. Mapping a change: using a theory of change to guide planning and evaluation. GrantCraft. 15: 2006. At: <www.grantcraft.org/index.cfm?pageId=808. >. Accessed 14 August 2009.

- J Kingdon. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. 2002; Longman: New York.

- Coffman J. Advocacy evaluation trends and practice advice. Advocacy Impact Evaluation Workshop. Seattle: Gates Foundation. Marc Lindenberg Center, University of Washington, Evans School of Public Affairs; 2 December 2007.

- K Guthrie, J Louie, T David, C Foster. The challenges of assessing policy and advocacy activities: strategies for a prospective evaluation approach. 2005; California Endowment. At: <www.calendow.org/reference/publications/pdf/npolicy/51565_CEAdvocacyBook8FINAL.pdf. >. Accessed 15 September 2009.

- D Leat. Theories of Social Change. International Network on Strategic Philanthropy. Paper 4. 2005; Bertelsmann Stiftung: Washington, DC. At: <www.peecworks.org/PEEC/PEEC_Inst/0021E1B7-007EA7AB.0/Leat%202005%20Theories_of_change.pdf. >. Accessed 15 September 2009.

- D Puttenney. Measuring social change investments. 2002; Women's Funding Network. At: <www.wfnet.org. >. Accessed 16 August 2009.

- B Klugman. Module 5: Policy. S Ravindran. Transforming Health Systems: Gender and Rights in Reproductive Health: A training curriculum for health programme managers. WHO/RHR/01.29. 2002; World Health Organization: Geneva, 299–380. At: <www.who.int/reproductive-health/publications/transforming_healthsystems_gender/index.html. >. Accessed 15 September 2009.

- B Klugman. Empowering women through the policy process: the making of health policy in South Africa. H Presser, G Sen. Women's Empowerment and Demographic Processes: Moving Beyond Cairo. 2000; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 95–118.

- M Pastor, R Ortiz. Making change: how social movements work and how to support them. 2009; Program for Environmental and Regional Equity, University of Southern California: Los Angeles. At: <www.calendow.org/uploadedFiles/Publications/Policy/General/Making%20Change%20-%20March%202009.pdf. >. Accessed 18 September 2009.

- L Korwin. The Catalyst Fund Theory of Change. 2009; Korwin Consulting for the Tides Foundation: San Francisco.

- J Reisman, A Gienapp, S Stachowiak. A Guide to Measuring Advocacy and Policy. 2007; Organizational Research Services: Seattle.

- C Albertyn, S Meer. Citizens or mothers? The marginalization of women's reproductive rights in the struggle for access to health care for HIV-positive pregnant women in South Africa. M Mukhopadhyay, S Meer. Gender Rights and Development: A Global Source Book, Gender Society and Development Series. 2008; Royal Tropical Institute: Amsterdam, 27–55. At: <www.kit.nl/net/KIT_Publicaties_output/ShowFile2.aspx?e=1456. >. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- B Klugman, M Stevens, K Arends. Developing women's health policy in South Africa from the grassroots. Reproductive Health Matters. 3(6): 1995; 122–131.

- G Marcus, S Budlender. A strategic evaluation of public interest litigation in South Africa. 2008; Atlantic Philanthropies: Johannesburg.

- D Robins. From revolution to rights in South Africa: social movements, NGOs and popular politics after apartheid. 2009; University of KwaZulu-Natal Press: Pietermaritzburg.

- Klugman B, Mokoetle K. Report on civil society's engagement with sexual and reproductive health and rights and opportunities for identifying an IPPF affiliate in South Africa. International Planned Parenthood Federation, Africa Region. 2010. Unpublished.

- Department of Health. Saving mothers. Second report on confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in South Africa 1999–2001. 2003; Department of Health: Pretoria.

- R Jewkes, H Rees, K Dickson. The impact of age on the epidemiology of incomplete abortion in South Africa after legislative change. BJOG. 112: 2005; 355–359.

- Republic of South Africa. White Paper on Population Policy. Pretoria: Ministry for Welfare and Population Development; April 1988. Notice 1930 of 1998. Government Gazette 399(19230). 7 September 1998.

- Department of Health. National Contraception Policy Guidelines – Within a Reproductive Health Framework. 2001; Department of Health: Pretoria.

- Department of Health. National Guidelines for Cervical Cancer Screening Programme. 2000; Department of Health: Pretoria.

- National Committee on a Confidential Inquiry into Maternal Deaths in South Africa. Saving Mothers 2005–2007: Fourth Report on Confidential Inquiries into Maternal Deaths in South Africa – Expanded Executive Summary. 2007; National Department of Health: Pretoria. At: <www.doh.gov.za/docs/reports/2007/savingmothers.pdf. >.

- D Bradshaw, M Chopra, K Kerber. Every Death Counts. 2008; South African National Department of Health: Pretoria.

- B Anderson, H Phillips. Adult mortality (age 15–64) based on death notification and data in South Africa: 1997–2004. 2005; Statistics South Africa: Pretoria. At: <www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report-03-09-05/Report-03-09-052004.pdf. >. 2006.

- M Khan, T Pillay, J Moodley. Maternal mortality associated with tuberculosis–HIV-1 co-infection in Durban, South Africa. AIDS. 15: 2001; 1857–1863.

- National Department of Health. Annual Report 2009/10. 2010:3. Pretoria.

- Margaret Hoffman, Professor, Women's Health Research Unit, School of Public Health and Family Medicine Health Sciences Faculty, University of Cape Town. Personal communication, March 2011.

- D Devlin-Foltz. Impact evaluation tools and methods: learning to live with imprecision and like it (mostly). Advocacy Impact Evaluation Workshop. 2 December. 2007; Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation: Seattle.

- C Letts, W Ryan, A Grossman. High Performance Nonprofit Organizations: Managing Upstream for Greater Impact. 1999; Wiley: New York.

- J Martineau, K Hannum. Handbook of Leadership Development Evaluation. 2007; Jossey-Bass/Center for Creative Leadership: San Francisco.

- S Ospina, E Schall. Leadership (re)constructed: how lens matters. 2001; APPAM Research Conference: Washington, DC.

- R Heifetz, D Laurie. The work of leadership. Harvard Business Review. January–February: 1997; 124–134.

- H Rees, J Katzenellenbogen, R Shabodien. The epidemiology of incomplete abortion in South Africa. South African Medical Journal. 87: 1997; 432–437.

- R Jewkes, H Brown, K Dickson-Tetteh. Prevalence of morbidity associated with abortion before and after legalisation in South Africa. BMJ. 324: 2002; 1252–1253.

- B Klugman, S Varkey. From policy development to policy implementation: the South African Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act. B Klugman, D Budlender. Advocating for Abortion Access: Eleven Country Studies. 2001; Johannesburg Initiative, Women's Health Project, School of Public Health, University of Witwatersrand. 251–282.

- S Friedman, S Mottiar. A moral to the tale: the Treatment Action Campaign and the politics of HIV/AIDS. 2004; Center for Civil Society, University of KwaZulu-Natal.

- A Boaz, S Fitzpatrick, B Shaw. Assessing the impact of research on policy: a review of the literature for a project on bridging research and policy through outcome evaluation. Policy Studies Institute. 2008; Kings College: London. At: <www.psi.org.uk/pdf/2008/bridgingproject_report_with_appendices.pdf. >. Accessed 20 September 2009.

- J Young. Impact of research on policy and practice. 2008. At: <www.capacity.org/en/content/pdf/4877. >. Accessed 15 September 2009.

- S Varkey, S Fonn, M Ketlhapile. The role of advocacy in implementing the South African abortion law. Reproductive Health Matters. 8(16): 2000; 103–111.

- E Mitchell, K Trueman, M Gabriel. Building alliances from ambivalence: evaluation of abortion values clarification workshops with stakeholders in South Africa. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 9(3): 2005; 89–99.

- R Sutton. The Policy Process: An Overview. 1999; Overseas Development Institute: London.

- J Trostle, M Bronfman, A Langer. How do researchers influence decision-makers? Case studies of Mexican policies. Health Policy and Planning. 14(2): 1999; 103–114.

- C Allan, D McAdam, D Pellow. What is the role of civil society in social change? Successful Social Movements. 2010. At: <http://chrisallan.info/wp-content/uploads/2010/04/Supporting-successful-movements3.pdf. >. Accessed 26 September 2010.

- S Jacobs, K Johnson. Media, social movements and the state: competing images of HIV/AIDS in South Africa. African Studies Quarterly. 9(4): 2007. At: <www.africa.ufl.edu/asq/v9/v9i4a8.htm. >.

- M Mbali. A long illness: towards a history of NGO, government and medical discourse around AIDS policy-making in South Africa. Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of an Honours Degree in History. December. 2001; University of Kwa-Zulu/Natal: Durban.

- M Stevens. From HIV prevention to reproductive health choices: HIV/AIDS treatment guidelines for women of reproductive age. African Journal of AIDS Research. 7(3): 2008; 353–359.

- C Eyakuze, D Jones, A Starrs. From PMTCT to a more comprehensive AIDS response for women: a much-needed shift. Developing World Bioethics. 8(1): 2008; 33–42.

- H Schneider. On the fault-line: the politics of AIDS policy in contemporary South Africa. African Studies. 61: 2001; 1.

- D Fassin, H Schneider. The politics of AIDS in South Africa: beyond the controversies. BMJ. 326: 2003; 495.

- F Westley, B Zimmerman, M Patton. Getting to Maybe: How the World is Changed. 2007; Vintage Canada: Toronto.

- R Shaw. The Activist's Handbook: A Primer. 2001; University of California Press: Berkeley.

- J Chapman. Monitoring and evaluating advocacy. PLA Notes. 43: 2002; 48–52. At: <www.planotes.org/documents/plan_04316.pdf. >. Accessed 15 September 2009.

- J Helzner. Guidelines on monitoring and evaluation: considerations for project design, implementation, and reporting. 2006; John D and Catherine T MacArthur Foundation: Chicago.

- K Newton. May the weak force be with you: the power of the mass media in modern politics. European Journal of Political Research. 45: 2006; 209–234.

- D Souter. The challenge of assessing the impact of information and communications on development. Building communication opportunities briefing. At: <www.bcoalliance.org/system/files/BCO_Synthesis_web_EN.pdf. >. Accessed 7 September 2009.

- E Mitchell, K Trueman, M Gabriel. Building alliances from ambivalence: evaluation of abortion values clarification workshops with stakeholders in South Africa. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 9(3): 2005; 89–99.

- R Jewkes, M Nduna, J Levin. Evaluation of Stepping Stones: a gender transformation HIV prevention intervention. Policy Brief. March. 2007; Medical Research Council: Pretoria. At: <www.mrc.ac.za/policybriefs/steppingstones.pdf. >.

- W Onyango-Ouma, R Laisser, M Mblilma. An evaluation of Health Workers for Change in seven settings: a useful management and health system development tool. Health Policy and Planning. 16(Suppl.1): 2001; 24–32.

- E Mitchell, K Trueman, M Gabriel. Accelerating the pace of progress in South Africa: an evaluation of the impact of values clarification workshops on termination of pregnancy access in Limpopo Province. 2004; Ipas: Johannesburg.

- M Grindle, J Thomas. Public Choices and Policy Change. 1991; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore.