Aid allocations by donor countries to sexual and reproductive health and rights and the values that underlie that aid are a timely and important topic. In general, data about such funding are weak and the field would benefit significantly from better and more comprehensive data on what the funds are earmarked for and how they are used. In the absence of such data, it is extremely difficult to address the issue objectively. This paper is a response to the paper by Sara Seims on improving the impact of sexual and reproductive health development assistance from the seven like-minded European donors.Citation1 It offers a different perspective on several of the key issues she raises.

Country ownership and accountability: the example of IHP+

Seims talks about two core values that currently guide the like-minded aid agencies – the autonomy of countries receiving aid (country ownership) and accountability for results. She suggests that in some cases the commitment to country ownership, as well as conflict between these two values, have resulted in reduced quantity and quality of funding for sexual and reproductive health and rights. However, I would suggest that these two programme values are not only essential but should be viewed as mutually reinforcing rather than conflicting. Thus, in cases where conflict between them does occur, recommendations would emphasize actions to ensure that complementarity between them is achieved. An example is the analysis of aid modalities.

Seims describes the trend in aid modalities since the early 1990s as moving towards sector support that emphasizes country autonomy but with insufficient accountability. On the other hand, she shows that in order to address the eight Millennium Development Goals, “vertical” global health initiatives have emerged, some of which have inappropriately excluded investments in sexual and reproductive health and rights. These are fair criticisms. However, she also expresses concerns about the International Health Partnership+ (IHP+), begun in 2007, in this regard, and there I disagree with her.

As a member of the Independent Advisory Group for the external assessment of the IHP+, I would defend the initiative and its potential importance for sexual and reproductive health and rights funding at country level. The IHP+ is a sector-wide endeavour. It is premised on country ownership and includes provisions to hold not only countries but also development partners accountable. It is notable that, to date, countries have been far better than donors in meeting reporting obligations under the IHP+.Citation2

Because IHP+ encompasses a commitment to equity, most signatories to it focus on women and children. The IHP+ is a process through which external development partners (donors, multilateral agencies) work with each other, the country's government and local civil society (the weakest partner in efforts so far) to agree on a single national health plan and budget. In the country-based negotiation of the national health plan and budget, the aim is that all parties work together to determine priorities which, in many instances, have included sexual and reproductive health services, equity, and adolescent health, among others. The parties then “harmonize” external and local resources for the agreed plan. Important objectives are to reduce the mushrooming of donor-initiated and donor-funded projects in the health sector, ease the management burden on the government, and rationalize use of both local/national and international resources so that health systems can better meet people's needs, especially the most vulnerable.Citation2

European donors, led originally by the United Kingdom, created the IHP+ based on their commitment to country ownership and accountability, and in response to the Paris and Accra agreements, not parallel to them. While the process of developing country “compacts” agreed by all key stakeholders, budgeting and delivering funds has been predictably slow and messy in the initial four years, four years is certainly too short a time to judge whether IHP+ is succeeding in achieving its health outcome goals. The initiative also has sector management and accountability objectives which receive at least equal attention in the evaluation process. The Independent Advisory Group for the external assessment of the IHP+ has urged that it be given more time, not only to see health benefits but to develop verifiable measures for aid effectiveness.

Seims references a pessimistic, earlier report, published in 2010,Citation3 but work since then has produced more progress on indicators, as presented in the 2011 report.Citation4 For example, in contrast to the 2010 report, the 2011 report has standardized indicators of health aid effectiveness, some of them verifiable. Although many of the indicators are of necessity based on self-reports, these reports are an “indicator” of the willingness of the signatories to participate in the accountability exercise which is itself one of the goals of the Paris and Accra accords. The evaluation methodology is complex and there are many areas that need improvement, such as how to interpret data collected on civil society participation in the IHP+ processes at country level. Nonetheless, progress so far gives reasonable hope for continued forward movement.

The need for better funding data

Seims' research asked how the like-minded donors programme their development aid for sexual and reproductive health and rights and how much money they provide for this. As she acknowledges, this is difficult to answer, partly because funding data are exceedingly constrained. As a result, various analysts produce different results using the same sources, despite heroic efforts to verify sources and synchronize definitions used. This highlights the pressing need for donors to improve their own data collection and reporting of how much of their aid goes to sexual and reproductive health and rights overall and to which aspects. Harmonization of reporting categories across donors would also be a major step forward. Without such more detailed and comprehensive data, it is difficult for any commentator to provide actionable insights.

The need to do more for sexual and reproductive health and rights

Seims urges the like-minded donors to encourage the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria to “do more in sexual and reproductive health and rights”, a worthy but hugely difficult cause that requires persistent and sustained attention to practical interventions, as well as to political considerations. Quite a few determined actors have been trying for some years, both through reports to the board and advocacy with members, to persuade the Global Fund to invest in reproductive health. Although not all the Fund's board members agree even now, the Fund supports reproductive health services provided the country has evidence of the connection between HIV incidence and such services, a very high standard to meet. The Open Society Foundation, long a board member of the Fund, has invested in a multi-year project to gather and rank all existing evidence of the relationships between reproductive health investments and improvement in HIV/AIDS indicators,Citation5 in order to help countries meet the standards of evidence set by the Technical Review Group, which assesses country proposals for the Fund.

Seims also recommends that the like-minded donors urge recipients of their general health support to use more of it for sexual and reproductive health and rights. This is vital, for example, in relation to the World Health Organization (WHO), whose Department of Reproductive Health & Research and related programmes receive less core budget support and support for staff positions than their importance warrants. What is needed is “political” encouragement by the donors with the Director-General and, as Seims suggests generally in her article, concrete mechanisms whereby the donors would hold WHO accountable for both the magnitude and strength of their work in this subject. Such mechanisms should include reports on programme content, staff and budgets, not only in absolute terms, but also relative to WHO's overall programme and core budgets.

Recommendations for improving aid impact and effectiveness: involving civil society

Seims expresses strong interest in improving the “impact and effectiveness” of donor investments at the country level. She calls on the like-minded European donors to use their embassy staff to advocate for civil society inclusion in the design and implementation of country-level health sector support programmes, for example. This is a vital contribution that donors could, but rarely do, make.

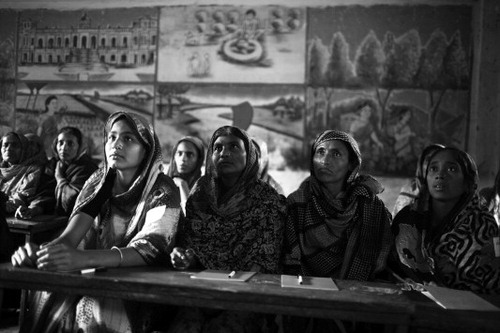

The Swedish government took such action to “invite NGOs in” with very significant effect in Bangladesh in the mid-1990s as part of the process of developing a new national health and population sector programme. This process provides an excellent example for what the IHP+ aims to do today. In essence, SIDA assigned specialist consultants to represent them in negotiations; insisted that time be allocated in the project design phase to allow for consultations with civil society; facilitated working groups and access to all materials, as well as orientation of NGOs before meetings with the government and development partners; and ultimately persuaded donors to appoint a civil society liaison in the World Bank (the lead donor agency) with specialized skills and a budget for village-based health watch groups, and working group and stakeholder meetings throughout a three-year process – all of which resulted in a national, five-year sexual and reproductive health programme funded at US$1.3 billion.Citation6

Seims also recommends that the donors create a special fund for strengthening NGOs. This idea has been discussed for some time, but has been stymied by complexities that must be addressed and taking account of the many pitfalls that need to be avoided. For example, one European government suggested a fund modelled on the Safe Abortion Action Fund run by the International Planned Parenthood Federation in London, but concerns such as the following surfaced during those discussions. First, an NGO serving as the host would face considerable challenges in maintaining, and being seen to maintain, objectivity. Second, that NGO would inevitably gain substantial power and influence, not necessarily constructive in the NGO community. A fiscal agent (an organization not in the field but with experience in soliciting proposals and managing grants), on the other hand, might not have sufficient capability and judgment, and professionals or organizations in the field asked to advise them could have allegiances or vested interests. It would be quite useful to encourage the like-minded donors to have a more rigorous and systematic discussion of possible NGO funding alternatives among themselves that also involves sexual and reproductive health and rights NGO representatives from all world regions.

Improving outcome measures

In assessing the donors' accountability, Seims criticizes existing indicators as particularly ineffective for persuading parliaments to invest in overseas development aid for sexual and reproductive health and rights. The hugely challenging question – what indicators are best and most essential – preoccupies several UN agencies, expert groups and assorted other institutions, even as countries stagger under ballooning reporting requirements. Everyone working in this area needs to give far more consideration to the strain on countries of having to meet a burgeoning list of targets and the indicators associated with them. Rather than add more, I would suggest a paring down, along with better use of the information currently collected. One possibly useful innovation could be to create a “Reproductive Health Effort Index” analogous to that currently produced by the Health Policy Initiative every five years to measure family planning efforts (inputs).Citation7 Footnote*

Seims also calls for assessments to determine which interventions are most impactful and cost effective – a vital issue. Those working on this challenge immediately face obstacles such as significant and desirable interventions begun and implemented without a baseline; or lack of vital data, especially on costs, and even agreement on what costs should be measured. In addition, the standard of measurement is often inappropriate. For example, many donors today, notably the Global Fund as mentioned above and the Gates Foundation, require a standard of evidence based on the biomedical model of clinical trials. These trials test interventions, such as drugs, by using at least two groups (one that receives the intervention, and the control group which does not) that are followed closely from the beginning of the intervention using very precise, usually quantitative, measures. This approach is often not feasible for interventions such as education that may show results years later, or where it is not feasible to have a “control group”.Footnote†

Another standard of evidence inappropriately applied to social and behavioral interventions by the Technical Review Group of the Global Fund is the requirement that a particular intervention directly result in reduced incidence of an undesired outcome (e.g. HIV infection). A behavioural intervention may not itself have such a direct effect but may be an essential part of the chain leading to risk reduction. Finally, Seims mentions the need to measure the value of investing in advocacy – also not measurable using the biomedical approach and addressed ably by Klugman in this journal issue.Citation8

Strengthening UNFPA

In several places, Seims both highlights the central importance of UNFPA and recommends that the like-minded donors work with UNFPA to implement the recommendations of recent external reviews – including to improve transparency in uses of funds, to tighten programme focus and to develop and use stronger performance metrics. The new Executive Director of UNFPA, who arrived in January 2011 after the reviews were completed, has already taken serious actions towards the various recommendations, including a revised strategic plan and results monitoring framework, a new business plan, and various internal review processes.

Reflections

Many people have described, and will describe, the ODA elephant. Though each may see different parts of the elephant – or even different elephants – it is in everyone's interest to support development partners (donors and others) to act so that countries (not only governments, but also their people and civil society organizations) can own and be accountable for their health policies, programmes and budgets. This requires seeing country ownership and accountability as core, mutually reinforcing values. It is also essential that development partners hold themselves, and be held, accountable for their commitments in this regard.

The largest bilateral donor, the US, now shares these two values in principle. The Obama Administration has, for example, mandated country operational plans that are prepared at country level in consultation with local stakeholders. Practice is certainly not perfect, but where staff are receptive, coordination with other partners, government and civil society appears to be improving, offering the potential for more coherent and cohesive progress with all stakeholders (provided, of course, that the current policy survives the coming election.)

The field would benefit a great deal from more specific and coherent reporting by donors on what they fund, where, in sexual and reproductive health and rights. As they currently report their funding in disparate ways, it is nearly impossible to get a clear picture or to discern trends. It will likely get more difficult as more funding goes to the health sector at large, as Seims suggests. Thus, our monitoring and advocacy efforts will have to focus as much or more on services and programmes in countries and the actions of development partners to support them, not only the money flows.

Notes

* The Health Policy Initiative's report on this index states: “National programs to extend family planning to large populations began in the mid-1960s and now exist in most developing countries. They vary greatly in strength and coverage, as well as in the nature of their outreach. Periodic measures of their types and levels of effort have been conducted since 1972, showing increasing strength. These measures have been used as the only consistent assessment of program efforts, for all countries, over time. They have served to inform policy positions and resource allocations, as well as technical analyses of program impact on contraceptive use and fertility declines. Questionnaires, completed by 10–15 expert observers in each of 81 countries, score 30 measures of effort, each on a scale from 1 to 10. Additional measures assess four general program characteristics… The Index is meant to measure inputs, not outputs.”Citation6

† The International Women's Health Coalition recently commissioned a paper to assess the (in)appropriatenesss of the biomedical clinical trials model for assessing social and behavioural interventions in sexual and reproductive health, such as comprehensive sexuality education, which we expect will be accepted soon for publication.

References

- S Seims. Improving the impact of sexual and reproductive health development assistance from the like-minded European donors. Reproductive Health Matters. 19(38): 2011; 129–140.

- IHP+ Results. Strengthening accountability to achieve the health MDGs: annual performance report. 2010. At: <www.ihpresults.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/IHP-Report_English+Cover.pdf. >.

- D McCoy, R Labonte, G Walt. The IHP+: a welcome initiative with an uncertain future. Lancet. 377: 2011; 1835–1836.

- International Health Partnership and Related Initiatives (IHP+). IHP+ Core Team Report May 2010–April 2011. At: <www.internationalhealthpartnership.net/CMS_files/documents/ihp_core_team_report__may_2010ap_EN.pdf. >.

- What works for women and girls. Evidence for HIV/AIDS interventions. At: <www.whatworksforwomen.org/. >.

- R Jahan. Restructuring the health system: experiences of advocates for gender equity in Bangladesh. Reproductive Health Matters. 11(21): 2003; 183–191.

- J Ross, E Smith. The Family Planning Effort Index: 1999, 2004, and 2009. 2010; Futures Group, Health Policy Initiative, Task Order 1: Washington DC. At: <www.healthpolicyinitiative.com/Publications/Documents/1110_1_FP_Effort_Index_1999_2004_2009__FINAL_05_08_10_acc.pdf. >.

- B Klugman. Effective social justice advocacy: a theory-of-change framework for assessing progress. Reproductive Health Matters. 19(38): 2011; 146–162.