Abstract

Since 2005, the Government of India has initiated several interventions to address the issue of maternal mortality, including efforts to improve maternity services and train community health workers, and to give cash incentives to poor women if they deliver in a health facility. Following local protests against a high number of maternal deaths in 2010 in Barwani district in Madhya Pradesh, central India, we undertook a fact-finding visit in January 2011 to investigate the 27 maternal deaths reported in the district from April to November 2010. We found an absence of antenatal care despite high levels of anaemia, absence of skilled birth attendants, failure to carry out emergency obstetric care in obvious cases of need, and referrals that never resulted in treatment. We present two case histories as examples. We took our findings to district and state health officials and called for proven means of preventing maternal deaths to be implemented. We question the policy of giving cash to pregnant women to deliver in poor quality facilities without first ensuring quality of care and strengthening the facilities to cope with the increased patient loads. We documented lack of accountability, discrimination against and negligence of poor women, particularly tribal women, and a close link between poverty and maternal death.

Résumé

Depuis 2005, le Gouvernement indien applique plusieurs interventions en matière de mortalité maternelle, notamment pour améliorer les services de maternité, former les agents de santé communautaires et verser une allocation aux femmes pauvres si elles accouchent dans un centre de santé. Après des manifestations locales contre le nombre élevé de décès maternels en 2010 dans le district Barwani au Madhya Pradesh, en Inde centrale, nous avons mené une mission d'enquête en janvier 2011 sur les 27 décès maternels signalés dans le district d'avril à novembre 2010. Nous avons constaté une absence de soins prénatals, en dépit de niveaux élevés d'anémie, un manque d'accoucheurs qualifiés, l'incapacité à dispenser des soins obstétricaux d'urgence dans des cas évidents de besoin et des aiguillages de patientes n'ayant jamais abouti à un traitement. Nous présentons deux cas à titre d'exemple. Nous avons transmis nos conclusions aux autorités de santé du district et de l'État, et demandé l'application de mesures éprouvées de prévention des décès maternels. Nous remettons en question la politique d'encouragement financier pour inciter les femmes à accoucher dans des centres de mauvaise qualité sans d'abord garantir la qualité des soins et renforcer les installations pour leur donner les moyens de traiter le nombre accru de patientes. Nous avons mis en évidence le manque de responsabilisation, la discrimination et l'indifférence à l'égard des femmes pauvres, en particulier des femmes tribales, et un lien étroit entre pauvreté et mortalité maternelle.

Resumen

Desde el año 2005, el Gobierno de India ha iniciado varias intervenciones para tratar el problema de mortalidad materna,incluso esfuerzos para mejorar los servicios de maternidad y capacitar a trabajadores comunitarios de la salud, y dar incentivos de dinero en efectivo a las mujeres pobres que dan a luz en una unidad de salud. En el año 2010, tras protestas contra el alto índice de muertes maternas en el distrito de Barwani en Madhya Pradesh, en India central, realizamos una visita en enero de 2011 para investigar las 27 muertes maternas reportadas en el distrito desde abril hasta noviembre de 2010. Encontramos una ausencia de servicios de atención antenatal a pesar de los altos niveles de anemia, ausencia de asistentes de parto calificadas, incumplimiento de los cuidados obstétricos de emergencia en casos obvios de necesidad, y referencias que nunca produjeron tratamiento. Presentamos dos historias de casos como ejemplos. Llevamos nuestros hallazgos a funcionarios de salud distritales y estatales e instamos a que se implementen medios comprobados para la prevención de muertes maternas. Cuestionamos la política de dar dinero en efectivo a mujeres embarazadas para que den a luz en unidades de calidad deficiente sin antes garantizar la calidad de la atención y fortalecer las unidades para que puedan manejar el número cada vez mayor de pacientes. Documentamos la falta de responsabilidad, discriminación y descuido de las mujeres pobres, en particular las mujeres tribales, y una estrecha asociación entre la pobreza y la muerte materna.

Every year, some 80,000 women die due to pregnancy-related complications in India, the largest number of maternal deaths in any one country, with an estimated maternal mortality ratio in 2004–06 of 254 per 100,000 live births.Citation1,2 An estimated two-thirds of these deaths take place in the states of Assam, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, Rajasthan, Uttaranchal and Uttar Pradesh.Citation1 According to UNICEF, 61% of maternal deaths occur in women from dalit Footnote* and tribal communities.Citation2

Since 2005, the Government of India has initiated several interventions to address maternal mortality. For example, the National Rural Health Mission was launched in 2005 by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare with the goal of improving “the availability of and access to quality health care by people, especially for those residing in rural areas, the poor, women and children”. Investments were made in the provision of community health workers called Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) in every hamlet, development of infrastructure of facilities, capacity building for health workers, and the development of standards for public health facilities. Specifically, the National Rural Health Mission began providing funding for maternal health as one of its key areas, with special attention to the states mentioned above, which have the poorest health and development indicators.

The biggest policy initiative on maternal health, however, has been the push for greater institutionalisation of childbirth, based on the premise that moving women to institutions at the time of delivery would automatically result in better care and reduce maternal deaths. This has been promoted by the Janani Suraksha Yojana (Mother Protection Scheme) that gives conditional cash incentives to deliver in a facility. In the named states, women from families designated as below the poverty line are provided Rs.1400 (approximately US$ 31) to deliver in institutions, roughly equal to the total monthly income of a tribal family in those states. Evaluations have shown that these incentives have had a significant effect on increasing use of antenatal care and in-facility births. However, quality of care remains poor,Citation3,4 and it is not known whether maternal mortality has decreased under this programme. Recently, the Government issued national guidelines that mandate states to carry out maternal death reviews at both community and facility level.

From April to November in 2010, there were reports of 27 maternal deaths from the District Hospital in Barwani, a predominantly tribal district in southwestern Madhya Pradesh, central India. Nine of these deaths were reported in November alone. These deaths were brought to public attention by Jagrit Adivasi Dalit Sangathan, a social movement, and SATHI, a non-governmental organisation working in the area. There were two large-scale protests on 28 December 2010 and 12 January 2011 in Barwani, particularly including tribal women, regarding the high number of maternal deaths. In response, a fact-finding team undertook a visit to Barwani in January 2011 to study the factors contributing to these deaths.Citation5 We present here an analysis of the contributory factors, based on verbal autopsies, a review of case records, and observation and interviews during visits to the facilities.

Methodology

The fact-finding team consisted of the authors, an obstetrician, a health activist and a health systems analyst. Verbal autopsies were conducted by members of the team with the families of six of the deceased women who were living in the area where the local organisations who were our point of access worked. These families agreed to be interviewed and oral consent was given. The team also had access to the District Hospital's case records of all 27 deceased women and to the referral records of other women who had been referred on from the District Hospital.

In addition, the team undertook visits to local public and private health facilities, including the District Hospital, one Community Health Centre and one Primary Health Centre, to study the infrastructure and quality of care provided in them and to interview 12 health care staff at these facilities, including medical officers, obstetricians, nurses and auxiliary nurse-midwives. Several policy and programme documents related to maternal health were also perused, including district programme implementation plans for the National Rural Health Mission, guidelines of various maternal health schemes of the government and state level audit reports.

Findings

Of the 27 reported maternal deaths, 26 were on the government list of maternal deaths and one was reported by the District Hospital as a referral to a higher centre, though it was found during the investigation that the woman actually died in the District Hospital. This may not be a true picture of the situation in the district, however, as there was no maternal death reporting system and there were no data on how many deaths had occurred at home or in transit to or from facilities.

Causes of death investigated

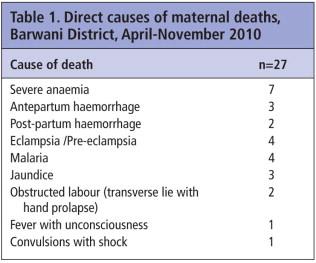

Twenty-one of the 27 women who died belonged to Scheduled Tribes, who are indigenous people outside the traditional caste system, one of the poorest and most vulnerable sections of society, with considerably less access to health care services than non-tribals and other castes. This percentage is disproportionately large even for Barwani, where Scheduled Tribes constitute 67% of the population. Table 1 shows the direct causes of death.

Access to treatment and quality of care

Antenatal care

Of the six cases for which we did verbal autopsies, only one woman had received any antenatal care, and this was restricted to tetanus toxoid injections. None of the other five had had any form of antenatal care, even those with high-risk pregnancies, such as previous caesarean section. No details regarding antenatal care could be obtained for the other 21 women, as this was not documented in the case records.

A lack of antenatal care was corroborated by observation during our field visits. The tiered health system in India consists of an auxiliary nurse-midwife or a multi-purpose worker providing services at village level, a Primary Health Centre for every 30,000 population, a Community Health Centre for every 100,000 population that provides secondary level care and is designated as a first referral unit, and a District Hospital providing tertiary level care. We found that auxiliary nurse-midwives based in Primary Health Centres and health subcentres, who are expected to function as skilled birth attendants, were not visiting the villages to provide antenatal care, as they were supposed to do, and that supportive infrastructure for such visits, including roads and transport systems, were lacking. The local ASHA was under-utilised, and many families had not even heard of the ASHA. Interviews with ASHAs revealed large gaps in essential knowledge of basic obstetric complications. In addition, peripheral facilities were ill-equipped and not fully functional; a Community Health Centre designated as the first referral level to provide comprehensive emergency obstetric care did not even have facilities to provide basic emergency obstetric care.

Antenatal care might have prevented some of the deaths. However, in spite of high levels of anaemia in the district, the District health plans did not have specific programmes to address either anaemia or its underlying causes, or malaria and sickle cell anaemia, which are highly prevalent in this district. Case records showed very high levels of anaemia in pregnant women. Of the 27 deceased women, 17 had had a haemoglobin level of 8 gms/dl or less, with five of them being severely anaemic with haemoglobin levels of 5gms/dl or less. During the team's visit to the District Hospital, on one day we found three pregnant women admitted to the wards with haemoglobin levels of 6, 4 and 2 gms/dl. Doctors at the District Hospital informed us that the hospital was doing 20–40 blood transfusions each day in pregnant women. We also learned from interviews with District health officials and perusal of District health plans that neither national nor district programmes addressing anaemia were being implemented. In fact, one Community Health Centre the team visited did not even have the facilities to estimate haemoglobin.

Post-partum care

We also found during interactions with families and health care providers that no system of postpartum care was in place. While programmes indicated that post-partum care should have been provided through auxiliary nurse-midwives and community health workers, in fact this was not happening on the ground. We also found that, very often, women were discharged from facilities soon after delivery instead of 48 hours later, as mandated by the programme, because of lack of adequate space. In other facilities, in contrast, women were forced to stay in facilities for 48 hours post-delivery without access even to toilets in order to receive the cash incentive.

Complications and attempts to obtain treatment

Twelve of the 27 deceased women who died in the District Hospital died in the ante-partum period, four intrapartum and 11 post-partum. Of the 11 who died post-partum, seven had delivered in a health care facility, six in the District Hospital and one at a Community Health Centre, and three at home; there was no information on place of delivery for one. We did find, however, that all 27 women had sought care in an institution once complications developed.

We traced the pathways that women followed to reach institutions that were able to treat them, in the six cases for which we did verbal autopsies. Three of the six women were referred for care to two or three institutions before finally arriving at the District Hospital, which has a functioning comprehensive emergency obstetric care centre with a blood bank and operating theatre facilities. The Primary and Community Health Centres were not equipped to provide initial emergency obstetric care or stabilise any of the women before referring them onwards. Moreover, 13 of the 26 women treated at the District Hospital were given a referral to an even higher facility – a public sector medical college in a city four hours away by road. However, none of the women could afford to make the journey and died in the District Hospital. Verbal autopsies also revealed that once a woman was referred onward, no responsibility was taken by the referring institution to ensure she was accompanied by a staff person for care during transit or that she reached the next institution safely.

As regards other women referred from the District Hospital onwards for emergency treatment, we were able to examine referral slips for 47 women in the period from 17 July 2010 to 21 January 2011. At least 16 of these referrals were for complications that needed immediate management, for example, ruptured uterus, inverted uterus, haemorrhage in shock, all of which the District Hospital should have been able to handle. We were unable to get the case records of these women and therefore have no details of what happened to them, including after they left the District Hospital.

Of the six deceased women whose families we met, only three were able to avail the use of the state-run ambulance services for transport. As we will show, lack of transport to facilities continues to be a major contributory factor in maternal deaths. Several of the families interviewed reported having to spend considerable sums of money to hire private vehicles for transport of the women. This resulted in long delays when there were referrals from one facility to another.

Conditions in facilities

Observations during facility visits revealed that the Janani Suraksha Yojana cash incentives had increased the maternity workload of the District Hospital and Community Health Centres due to increased numbers of women presenting for delivery. Studies show that institutional deliveries in Barwani district increased from 17.4% of total deliveries in 2003 to 29.4% in 2008 and 58.3% in 2009. However, over 60% of these deliveries took place in higher level facilities like the District Hospital or Community Health Centres.Citation4

Duration of stay in the District Hospital of the 27 deceased women ranged from 30 minutes to more than 43 hours. A review of case records revealed long third-phase delays in at least 10 of the 27 deaths. These included delays in starting definitive management for delivery in four women with eclampsia, delays in controlling and treating haemorrhage in two women, delays in operative management of obstructed labour in two women, and delays in managing shock in two women. None of the 27 women who died in the District Hospital had had any emergency operative intervention, despite this being clearly indicated in at least seven cases. In fact, the quality of care in several of these cases was poor and in many instances, standard treatment protocols were not followed. For example, in none of the four cases of eclampsia/severe pre-eclampsia was any attempt made to hasten delivery either through induction or augmentation of labour or through operative delivery. In some cases, the quality of care was so poor that it may be considered negligent. Moreover, in both cases of death due to obstructed labour, the women had been admitted with transverse lie with hand prolapse. However, no attempt to deliver them by caesarean section was made, even though the women remained in hospital for more than three and six hours, respectively.

The District Hospital was fully equipped to do caesarean sections and, in fact, was doing several every month. Of approximately 400 deliveries in the District Hospital every month, about 20 were delivered by caesarean section. This is, however, much below the expected 5–15% caesarean section rate for a community, let alone for a tertiary referral centre like the District Hospital. In fact, the operating theatre there was well-equipped to perform all types of obstetric and gynaecological surgery, yet no emergency operations were being performed at night. This was partly because the hospital was ill-equipped to handle the increased patient load in terms of human resources and infrastructure. Although four obstetricians were posted at the District Hospital, they were frequently away on training or doing female sterilisation operations. Doctors interviewed reported extreme stress and pressure and were waiting to get out of government service. There was a severe shortage of skilled staff – the entire women's section of 60 beds, including the Labour Room in the District Hospital, was staffed with five nurses, two on morning shift, two on evening shift and one on night shift.

Staff capacity and motivation at all levels were found to be very low. Furthermore, no standard management protocols such as the use of partographs were followed, infection prevention measures were found to be inadequate, and the level of cleanliness was unsatisfactory. Women patients also reported instances of verbal and physical abuse by staff during delivery, and tribal women felt they were discriminated against by health care providers.

We found that user fees were being widely charged in the public sector facilities.Footnote** Even when women were certified to be below the official poverty line and thus eligible for free drugs and services, many families had to pay out of pocket for drugs, diagnostics and other services.

Skilled birth attendants

The JSY is based on the assumption that once women are brought to institutions, they will automatically be attended to by skilled birth attendants. We found that this was not true. Deliveries in Primary and Community Health Centres were conducted by nurses or nurse-midwives – who had, however, not received any training or certification in skilled birth attendance. In the district hospital, there were no skilled birth attendants available for deliveries either; instead, most deliveries were being managed by traditional birth attendants posted as helpers in the labour room as there was a severe shortage of nurses. In-service training, like that for nurses and auxiliary nurse-midwives in skilled birth attendance, was inadequate. Interviews with nurses revealed that their knowledge and skill levels with regards to obstetric complications and their management skills were inadequate.

Poor governance and accountability

One of the main issues emerging from our investigation was poor governance and accountability. Lack of accountability was demonstrated by the poor quality of care and apathy among the health professionals in the institutions and the frequent flouting of ethical principles in the provision of care, as narrated in the case histories here. There are serious issues in the culture of the district health system – corruption, individual personal gain, dereliction of duty – that need to be changed. We found pervasive corruption at all levels of the health system, which was documented in audit reports of various government schemes.

There was also a lack of any kind of grievance procedure or mechanism for redress. Moreover, when complaints were filed, there was no official response and District Health Officials would not agree to have a dialogue. Instead, there were threats of punitive action, including imprisonment, against families who had filed complaints, and charges were slapped on people who had protested against the deaths.Citation7

Lack of maternal death review

Maternal deaths were not reviewed regularly in the district, either in facilities or in the community, in spite of existing national guidelines institutionalising such reviews.Citation8

The World Health Organization recommends several process indicators for determining whether emergency obstetric care (EmOC) is sufficient, including number of EmOC services available per 100,000 population, their geographical distribution, the proportion of all births in EmOC facilities, the met need for EmOC, caesarean sections as a percentage of all births and case-fatality rate.Citation9 However, when we attempted to find data for at least some of these indicators for Barwani district, we found that the data being collected in the Health Management Information System were inadequate. Numbers of institutional deliveries and payments of cash incentives for using them were the only yardsticks used for measuring progress on reducing maternal deaths. These showed a significant increase in institutional deliveries since the beginning of JSY and payment of corresponding cash incentives.

Case histories

We present case histories of two of the women who died, to illustrate our findings.

Garli Bai

Garli Bai, 32 years old, belonged to the Bhil tribe and lived in a village in a district neighbouring Barwani. This was Garli Bai's third pregnancy. Her first child died immediately after delivery. Her second pregnancy ended in a stillbirth and was delivered by caesarean section in the District Hospital in Barwani. In this pregnancy, Garli Bai did not receive any antenatal care, only a tetanus toxoid injection by a multi-purpose worker.

On the night of 16 July 2010, Garli Bai started getting pains. She was taken to a Primary Health Centre at around 9:30pm, about 10 kms from her village. The transport in a private hired vehicle cost her family Rs.500 (approximately US$ 11). There was no doctor at the Centre. Over the phone, a doctor advised her relatives to take her to Barwani District Hospital. The relatives say that the baby's hand had appeared while she was at the Centre. Garli Bai was taken to Barwani District Hospital, arriving around 10pm.

The case records document that she was admitted to the District Hospital at 11:50pm with a diagnosis of hand prolapse, severe anaemia, severe pallor, blood pressure of 120/80 mm Hg and previous lower segment caesarean section. Abdominal examination revealed a 36-week uterus with the fetus in transverse lie with no audible fetal heart. A per vaginal exam showed a fully dilated cervical os with a prolapsed hand. Blood investigations revealed haemoglobin of 10 gms/dl and blood group B-negative. Intravenous fluids were started, one unit of blood was transfused, and it was planned to prepare for a caesarean section. According to Garli Bai's relatives, they had to purchase medicines from outside the District Hospital for Rs.500 despite the family being below the official poverty line and thus eligible for free medicines.

The relatives said that at around 3am, instead of performing the caesarean section, the doctor advised them to take her immediately to the next referral centre at Government Medical College, Indore, four hours away by road. The referral letter states that she was referred to Government Medical College, Indore, as her blood type was not available in the blood bank. The relatives were asked to hire a private vehicle and were told that an ambulance could not be provided for transport to Indore. However, the relatives could not afford the cost of the vehicle, and took her back to the village.

By 8am the next morning, Garli Bai's condition had further deteriorated. Her relatives took her back to the PHC in a school van. The doctor told them that her condition was serious, and that she should be taken to Barwani again. In view of their experience the previous day, the relatives were reluctant to do this, but finally took her back to Barwani District Hospital. There, the same doctor who had seen her the previous night was on duty and refused to see her again, as he had referred her to Indore the previous night. For over one hour, the relatives pleaded with the doctor and other staff to treat her, but to no avail. Garli Bai remained in the vehicle this whole time. At around 1:30pm she died in the vehicle. Her body was taken home in a private vehicle.

This case was recorded as a referral in the official records – not as a maternal death in the District Hospital.

Durga Bai

Durga Bai, aged 32 years, belonged to a scheduled tribe and lived in a village in Barwani district. Durga Bai was married for 13 years and had had six pregnancies, of which four children were living and two had died. In her seventh pregnancy, Durga Bai had received no antenatal care, no folic acid or iron supplements, no tests or immunisation. An auxiliary nurse-midwife had visited her but did not have any tetanus toxoid injection with her. Instead of returning with the injection, she asked Durga Bai to come to the Community Health Centre.

During previous pregnancies, Durga Bai had not had any complications or problems. On 26 December 2010, she experienced labour pains and was taken to the CHC at 2pm. Upon examination, the nurse found that she was ready for delivery. Durga Bai was made to lie on a bed, and given an injection, purchased by her family for Rs.20. Soon both the legs and one hand of the baby came out. However, the baby's head was stuck inside, and the nurse sent for the doctor on duty. The doctor advised Durga Bai to go to Barwani District Hospital. The referral letter states the time of referral as 2:30pm, with a diagnosis of “breech presentation with lock head - whole fetus comes out but head not comes out and there is no pains. BP normal.” After an hour Durga Bai's relatives took her by ambulance to the District Hospital, 22kms away.

She was admitted at 3:50pm with excessive pallor. Abdominal examination showed a 24-week uterus. On vaginal examination, the cervical os was fully dilated and the aftercoming head obstructed. She was started on intravenous fluids and antibiotics, which the family purchased for Rs. 400. According to Durga Bai's mother, the nurse then tried to force the baby out by pushing. Records show that a stillborn baby weighing 2.8kg was delivered at 5:35pm and the placenta delivered five minutes later. Durga Bai's haemoglobin was 2 gms/dl.

According to her mother, there was continuous bleeding during this time. The case records also document excessive bleeding at 6:30pm. Though Durga Bai required blood, the hospital did not provide it and instead referred the family to a donor, who charged Rs.1600 (US$ 36) for one unit of blood. Since they had no money with them, Durga Bai's mother pawned a silver necklace for Rs. 1000 (US$ 22). After receiving only a couple of drops of blood, Durga Bai died. The doctor, who was called by the nurse, arrived only after her death.

Vyapari Bai, Durga Bai's mother, was deeply traumatised and broke down repeatedly while narrating her daughter's story. She expressed deep guilt at not being able to save her daughter. It appears that the child had hydrocephalus, as Vyapari Bai described him as having a huge head. The family is extremely impoverished; at the time of our interview, they had not yet been able to recover the silver necklace and continued to be in debt.

Discussion

There is a serious crisis of governance and accountability within the health system in Barwani district. The stories of Garli Bai and Durga Bai and those of the other women whose deaths the team investigated raise many issues. The National Rural Health Mission made a commitment in 2005 to provide good quality maternity services within the Indian Public Health Standards.Citation10 However, in Barwani district, in 2010, many of these standards remained unachieved.

Our findings show that the policy of institutionalisation of childbirth alone does not necessarily result in better maternity care or fewer maternal deaths. We found an absence of institutional readiness to handle increased numbers of women presenting for deliveries or to provide emergency obstetric care, and that the focus on institutional deliveries had resulted in a lack of attention to antenatal and post-partum care. The exclusive focus on cash incentives needs to be questioned. It is unethical to push women to deliver in institutions when the state cannot ensure that they will receive adequate care.

Accountability of the health system is an important aspect of good governance. Previous studies in India, e.g. in Karnataka in 2007, have shown that the lack of accountability mechanisms in service delivery can lead to maternal deaths.Citation11 Given the extreme degree of social inequity in Barwani district and the hierarchical nature of the health system, accountability cannot be ensured unless specific attention is paid to addressing power relations. Marginalised groups such as tribals face significant obstacles when demanding accountability;Citation12 tribal women are doubly disadvantaged because of caste and gender power hierarchies.

The investigation found the working conditions of medical and paramedical staff to be very poor and supportive supervision lacking at all levels. There was a lack of awareness of social determinants of health and ethics in medical and paramedical training, visible in daily practice. The entrenched culture of the public health system, which is inherently hierarchical and apportions blame to the lowest possible level, led to the “do not take any risk, pass the buck to the next level” attitude.

The investigation also revealed a close link between poverty and maternal deaths. This was characterised by serious malnutrition among women in the area and low coverage of antenatal care. User fees resulted in poor women being unable to access care in times of need. Given ample evidence that user fees adversely affect equity in access to services, continuing to expect women to pay out of pocket for public services is unacceptable, particularly when government policy exempts them. Compounding this was the systemic neglect in this district of adequate communication and transport facilities, with responsibility in life-threatening situations transferred to poor families.

The investigating team also felt that the roles of the traditional birth attendants (TBAs) and auxiliary nurse-midwives need to be re-examined, given the local context. In an area where no services are accessible, let alone health care services, how does the health system ensure that an auxiliary nurse-midwife can provide a basic minimum package of services to the remotest corners, unless for example, she has mobility support. In remote areas, the role of the ASHA as complementing the auxiliary nurse-midwife, in addition to her role as a community health activist, also needs to be re-considered, and capacity building and supportive supervision need to be planned accordingly. And what about traditional birth attendants? In the push to institutionalise deliveries, it is indeed ironic that women have to travel long distances to institutions to be delivered by the same TBAs they could have accessed much closer to home. Innovative solutions are needed to provide women with safe childbirth services closer to home, as well as access to emergency obstetric care.

Recommendations

We recommended that Madhya Pradesh officials initiate the following changes in the management of the health system:

immediate action to ensure there are proper, functioning maternity services with 24-hour coverage for prevention of maternal deaths, including antenatal care and safe abortion services as part of primary health care in the tribal districts, for which the State must develop a realistic plan;

reduction of unnecessary or unwarranted referrals, e.g. with the intention that women die somewhere else;

regular maternal death reviews in all districts, ensuring that all deaths are recorded and studied, including review of all referrals, using national guidelines;

use of pregnancy-related data in the Health Management Information System by heath workers to improve care without fear of punitive action;

participatory monitoring of health services to increase transparency, e.g. district-level quarterly reviews based on WHO recommended indicators;Citation9

analysis of data from both district and state level to be made public through regular reports, and to include explanation of policy on responsive remedial action; and

sensitisation and reflection workshops for health staff at all levels as part of an organisational development effort, addressing professional ethics, commitment to duty, sensitivity to the concerns of the poor, tribals and women, power relations, the Indian Constitution, human rights, and respect for all individuals.

For patients in hospital, there should be the following initiatives to improve accountability:

guaranteed health services displayed in all facilities, enabling people to be aware of and know they can ask for these services;

help desks at hospitals;

a grievance procedure within the district health system, including an immediate response system and systemic review with correctional mechanisms in place, such as ombudspersons to hear grievances and handle timely redress; and

mass maternal health awareness campaigns.

For provision of maternity care at all levels, there should be:

adequate staffing, and better management and support;

better coverage and availability of obstetrician-gynaecologists;

in-service training for ASHAs and monitoring of the care they provide;

provision of midwifery skills training for auxiliary nurse-midwives;

ensuring that Primary and Community Health Centres and sub-centres can provide good quality antenatal care and handle normal deliveries; and

identification of traditional birth attendants with midwifery skills and their capacities increased to handle normal deliveries, identify complications and make referrals early, including with direct links to emergency obstetric care, especially in geographically difficult-to-reach and any other areas where more highly skilled birth attendants do not exist.

Continuity of care from antenatal care to delivery and post-partum care with skilled midwives and with access to emergency obstetric care must be ensured, through an agreed package of community-based services that are regularly available in the villages, so that women need not travel long distances for them. Patients who are unable to pay and in critical need of blood must receive it without delay free of cost. Systems to make referrals accountable should be developed, including provision of ambulances, and continuity of care as part of the referral system, through accompanied transfers.

The state must ensure commensurate investment into tribal areas to compensate for the historical disadvantage meted out to these populations, especially women, to improve literacy, livelihoods to reduce migration, food and nutritional security and attention to poor health. Maternal health determinants must be tackled through plans to control nutritional and other anaemia and supplementary nutrition programmes for prevention and treatment of malnutrition, including among adolescent girls.

The National Rural Health Mission has a mandate to improve maternal health, yet the increase in public spending on health has risen from a pitiful 0.9% of GDP to only 1.2%, against a promised 2–3%. While there have been continued efforts to improve the utilisation of allocated funds for health services by the states, with moderate success,Citation13 spending is primarily on family planning and Janani Suraksha Yojana. Delays in transfer of funds from the centre to the states leads to unspent balances at year end. However, states with poor indicators, where the need is greater, have weaker absorption capacities, leading to gross under-utilisation of allocated funds.Citation14 The challenge is to improve management capacity, including at the district and state levels, while ensuring increased allocation of resources for health.Citation15

Civil society organisations must function as vigilant watchdogs to ensure that quality maternity and health services reach the most marginalised sections of society. They must undertake awareness campaigns on nutrition, sickle cell anaemia and malaria – in order to effect a change at the household level, such as equitable distribution of food and other resources within the household. They must also engage with the health system at all levels as health rights advocates.

At the national level, the current policy focus on institutional deliveries and Janani Suraksha Yojana needs to shift to improved maternity services, with continuity of care from antenatal care to delivery and post-partum care with skilled midwives and with access to emergency obstetric care. Indicators for maternal health must move beyond the number of cash incentives given and number of institutional deliveries to include the WHO process and quality of care indicators. Indicators for assessing governance in the health sector need to be developed and operationalised.

Postscript

We presented our fact-finding report to district and state health officials, who promised corrective action. We went back to Barwani district eight months after the initial study to find out what changes, if any, had been instituted and their effect on maternal health. We found certain positive improvements, including initiation of maternal death reviews, implementation of peripheral level antenatal care by auxiliary nurse-midwives on fixed days, training and skills-building interventions for staff, use of standard protocols such as routine active management of third stage of labour, a decrease in referrals from the District Hospital, evidence of operative interventions at night and improvements in recording formats.

However, several areas of concern still remain, including a continuing skilled staff shortage, absence of a grievance procedure, no provision of safe abortion services and very low staff morale. In addition, discussions with district and state officials revealed that many of these positive interventions were confined to Barwani district, where the issues had received much attention but not in other districts, which had similar problems. We therefore again presented our findings and recommendations to district and state level health authorities.

Notes

* The lowest caste in the traditional hierarchy, earlier called “untouchable”.

** User fees were introduced in public health facilities in Madhya Pradesh in 1997-98 as part of health sector reforms. Citation6.

References

- Registrar General of India. Special Bulletin on Maternal Mortality in India 2004–06. Sample Registration System. 2009; Registrar General of India: New Delhi.

- UNICEF. Maternal and Perinatal Death Inquiry and Response. 2009. At: www.mapedir.org. Accessed 5 February 2011.

- SS Lim, L Dandona, JA Hoisington. India's Janani Suraksha Yojana, a conditional cash transfer programme to increase births in health facilities: an impact evaluation. Lancet. 375: 2010; 2009–2023.

- National Health Systems Resource Centre. Programme Evaluation of the Janani Suraksha Yojana. 2011; NHSRC: New Delhi. At: http://nhsrcindia.org/pdf_files/resources_thematic/Public_Health_Planning/NHSRC_Contribution/Programme_Evaluation_of_Janani_Suraksha_Yojana_-Sep2011.pdf. Accessed 1 January 2012.

- B Subha Sri, N Sarojini, R Khanna. Maternal deaths and denial of maternal health care in Barwani District, Madhya Pradesh: Issues and concerns. 2011; SAMA: Jan Swasthya Abhiyan, CommonHealth.

- World Health Organization. Health Sector Reforms in India: Initiatives from Nine States. 2004; World Health Organization: New Delhi.

- Shukla A, Chakravarthy I, Rinchin. Five Years of NRHM-JSY and more than a decade of RCH: continuing maternal deaths in Barwani and MP. Unpublished report, 2011.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. National program implamentation plan – Reproductive & Child Health Phase II program document. 2005; MoHFW: New Delhi. At: http://mohfw.nic.in/NRHM/RCH/guidelines/NPIP_Rev_III.pdf. Accessed 18 February 2012.

- UNICEF. Guidelines for monitoring the availability and use of obstetric services. 1997; UNICEF: New York.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. National Rural Health Mission (2005–2012) Mission document. 2005; MoHFW: New Delhi. At: http://mohfw.nic.in/NRHM/Documents/Mission_Document.pdf. Accessed 18 February 2012.

- A George. Persistence of high maternal mortality in Koppal District, Karnataka, India: observed service delivery constraints. Reproductive Health Matters. 15(30): 2007; 91–102.

- A George, A Iyer, G Sen. Gendered health systems biased against maternal survival: preliminary findings from Koppal, Karnataka, India. Institute of Development Studies Working Paper 253. 2005; IDS: Brighton.

- N Bajpai, JD Sachs, RH Dholakia. Improving access, service delivery and efficiency of the public health system in rural India - mid-term evaluation of the National Rural Health Mission. CGSD Working Paper No. 37. 2009; Center on Globalization and Sustainable Development, Earth Institute: Columbia University. At: www.earth.columbia.edu. Accessed 1 January 2012.

- I Agarwala, T Agarwala. Safe motherhood, public provisioning and health financing in India. 2009; Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability: New Delhi. At: http://www.cbgaindia.org/files/research_reports/Safemother%20hood%20final%20file%20%281%29.pdf. Accessed 1 January 2012.

- National Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. Report of the National Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. 2005; Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India: New Delhi. At: http://www.who.int/macrohealth/action/Report%20of%20the%20National%20Commission.pdf. Accessed 1 January 2012.