Abstract

Maternal and neonatal mortality in the post-partum period remain high in many countries because of the limited provision of care. This study uses Demographic & Health Survey data for Egypt in 2005 and 2008 and Bangladesh in 2004 and 2007 to analyse levels and trends in post-partum and post-natal care by place of delivery. Improvements were found in levels and timing of post-partum care following institutional deliveries in both countries, especially within 24 hours post-partum. In Egypt, post-partum care within 24 hours rose from 86% to 93% between the two surveys, and in Bangladesh from 46% to 67% (data for home deliveries only). In contrast, although most first neonatal care was within 24 hours, few improvements were seen in the proportion of infants receiving early care after institutional or home deliveries. If the first hour after delivery were excluded from our analysis, more than 40% and 78%, respectively, of the level of institution-based post-partum care in Egypt in 2008 and Bangladesh in 2007 would be excluded, implying that post-partum coverage may be far worse than DHS data indicate. This study shows that post-partum and post-natal care – like skilled attendance and emergency obstetric care – continue to be grossly neglected and lag far behind the high and rising levels of antenatal care in a growing number of countries.

Résumé

La mortalité maternelle et néonatale pendant le postpartum demeure élevée dans beaucoup de pays en raison de soins limités. Cette étude utilise les données des enquêtes démographiques et sanitaires (EDS) en Égypte en 2005 et 2008 et au Bangladesh en 2004 et 2007 pour analyser les niveaux et les tendances des soins postnatals et du postpartum par lieu de prestation. Dans les deux pays, des améliorations ont été constatées dans les niveaux et les délais des soins du postpartum après les accouchements en institution, en particulier les premières 24 heures. En Égypte, les soins du postpartum dans les 24 heures sont passés de 86% à 93% entre les deux enquêtes, et de 46% à 67% au Bangladesh (données uniquement pour les accouchements à domicile). Par contre, même si la plupart des premiers soins néonatals étaient donnés dans les 24 heures suivant la naissance, peu d'améliorations ont été observées dans la proportion de nourrissons recevant des soins précoces après un accouchement en institution ou à la maison. Si l'on ne tient pas compte de la première heure après l'accouchement, plus de 40% et 78%, respectivement, du niveau des soins du postpartum en institution en Égypte en 2008 et au Bangladesh en 2007 seraient exclus, ce qui fait craindre que la couverture des soins du postpartum ne soit bien pire que ce qu'indiquent les données des EDS. Cette étude montre que les soins postnatals et du postpartum, comme l'assistance qualifiée et les soins obstétricaux d'urgence, continuent d'être grossièrement négligés et sont très en retard sur les niveaux élevés et croissants des soins prénatals dans un nombre grandissant de pays.

Resumen

Las tasas de mortalidad materna y neonatal en el período posparto continúan siendo altas en muchos países debido a la limitada prestación de servicios. En este estudio se utilizan los datos de la Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud realizada en Egipto en 2005 y 2008, y en Bangladesh en 2004 y 2007, para analizar los niveles y las tendencias en la atención posparto y posnatal por lugar del parto. En ambos países, se encontraron mejoras en los niveles y el momento oportuno de la atención posparto brindada después de partos institucionales, especialmente en el plazo de 24 horas posparto. En Egipto, la atención posparto durante ese plazo aumentó del 86% al 93% entre las dos encuestas; en Bangladesh, del 46% al 67% (datos de partos caseros solamente). Por contraste, aunque gran parte de la primera atención neonatal fue brindada en el plazo de 24 horas, se vieron pocas mejoras en la proporción de recién nacidos que recibieron atención temprana después de partos institucionales o caseros. Si se excluyera de nuestro análisis la primera hora después del parto, se excluiría más del 40% y el 78%, respectivamente, del nivel de atención posparto institucional en Egipto en 2008 y en Bangladesh en 2007, lo cual implica que la cobertura posparto podría ser mucho peor que lo que indican los datos de la EDS. Este estudio muestra que la atención posparto y posnatal – como atención calificada y cuidados obstétricos de emergencia – continúan siendo terriblemente descuidadas y van muy a la zaga de los altos y crecientes niveles de atención antenatal en un número cada vez mayor de países.

In monitoring progress towards the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), it has become evident that indicators of maternal and neonatal mortality have seen little improvement in low-income countries and some middle-income countries.Citation1,2 Successes in reducing the under-five mortality have been largely due to increased uptake of interventions among children after the first month of age.Citation3

The major causes of maternal and newborn mortality and their timing in relation to pregnancy and childbirth are well known. For maternal mortality, they include haemorrhage, sepsis, eclampsia, obstructed labour and complications of abortion, which together account for about 70% of maternal deaths.Citation4,5 The leading causes of newborn mortality include infections, prematurity, asphyxia and other intrapartum-related conditions, together accounting for 86% of neonatal deaths.Citation6 Most deaths in both women and newborns occur within a few hours of delivery, mostly the first 48’hours. For example, the average time to death from untreated post-partum haemorrhage is about two hours.Citation7 This is a critical period, when interventions that have significant potential for reducing mortality are needed.

In this paper, I use the terms “post-partum care” to refer to care for mothers after childbirth and “post-natal care” to refer to care for newborn infants. Some publications use “post-natal care” to include both women and babies; others use “post-partum care” to include both. Still others use both terms inconsistently for one or the other. This is confusing; unless the two kinds of care are clearly distinguished, it will not be clear whose care is being referred to.

Post-partum and post-natal care are key components of the “continuum of care” for women and babies.Citation8,9 The continuum starts when a girl receives information and services during adolescence, continues throughout pregnancy, childbirth, the post-partum period and thereafter, and includes newborn, infant and child health care as well.

Post-partum care for women could not only prevent 60% of maternal deaths but also the acute and chronic morbidity arising from pregnancy and delivery-related complications. Post-natal care is an important opportunity to support exclusive breastfeeding, immunization, family planning and prevention of HIV infection. In spite of their importance, however, there is currently neither agreement on a core package of care nor widespread provision of care, and coverage ranks lowest along the continuum. Moreover, accurate estimates of coverage are hard to obtain because routine statistics and surveys do not collect this information.

The Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) have for more than 25 years collected population-based data for about 80 developing countries,Citation10 and have provided valuable information on antenatal and delivery care by skilled attendants. However, the data collection instrument includes questions on post-partum/post-natal care only for women delivering at home, not in a health facility. For example, a study of DHS data for 30 developing countries from 1999 to 2004 found that nearly half of all births occurred outside health facilities, and in 70% of those the women had not received any post-partum care.Citation11 There appears to be an assumption that if women deliver at a health facility they have received post-partum/post-natal care, which may well not be true.

The first two countries to modify their DHS questionnaires to include information on post-partum and post-natal care for all interviewed women, regardless of where the delivery took place, were Bangladesh and Egypt – for two surveys each to date. This paper presents data from these surveys on coverage of post-partum and post-natal care.

Methods

DHS questions and data

The data come from the DHSs for Egypt conducted in 2005 and 2008 and for Bangladesh conducted in 2004 and 2007. The data relate to the surveyed women's most recent live birth in the five years prior to the survey date. In the case of multiple births, the birth coded by the interviewer as the most recent one was used. The bias for using a woman-based approach rather than a birth-based approach to derive pregnancy and delivery-related indicators is considered small.Citation12 The surveyed populations were women aged 15–49 years, and the samples were nationally representative.

The questions used in these surveys covered the timing of the occurrence of care, and the person who provided it. Women delivering in a facility were asked whether it was public or private. Typical questions for post-partum care were:

After (NAME) was born, did a health professional/medical person check on your health? IF YES, who checked you at that time?

For post-natal care, similar questions were asked.

In the Egypt DHSs, for women delivering at a health institution, the questions for first post-partum care were broken down for before and after discharge, to allow for care that only occurred after discharge. For after discharge, the question started: “At any time in the two months after you were discharged…”. “Total” care was the sum of the data for before and after discharge. There was no indication of the usual period of hospitalization for normal or complicated deliveries in either country as the DHS did not ask about this.

It is also not clear whether care in the first hour after delivery of the placenta is considered intra-partum or post-partum care. The 1998 WHO definition of “the post-partum period, or puerperium” starts about an hour after the delivery of the placenta’and includes the following six weeks.Citation13 A more recent WHO publication describes the first hour after delivery of the placenta as the “immediate post-partum period”,Citation14 while the 2010 WHO technical consultation that reviewed post-partum and post-natal care defined the “immediate post-natal period” as the time “just after childbirth” and covering “the first 24 hours from birth”.Citation15

For the post-partum care analysis we included care for the woman within the first hour after birth. As the question on timing asked about “after delivery”, the women may not have stated with precision the specific time when the first post-partum check occurred. Moreover, the greater the time between the last birth and the survey, the less accurate the recall of the specific time was likely to be. Additionally, one qualitative study suggests that not all women may understand what “a check on your health” is.Citation16 Because the timing and content of post-partum and post-natal care were not fully defined in the surveys nor necessarily implemented in practice,Citation14,15,17 women may not have known whether a visit constituted care per se or not. These and other limitations may affect the precision of the estimates.

Findings

Where deliveries took place: Egypt and Bangladesh

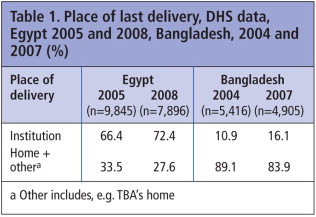

Table 1 shows where deliveries took place in the two countries. In Egypt, the great majority of births took place in health facilities; the situation was strikingly opposite in Bangladesh. Starting from a much lower base, between the two survey periods, however, Bangladesh increased institutional deliveries by 50% compared to a less than 10% increase in Egypt.

In the following sections, information about post-partum care and post-natal care are presented separately for Egypt and Bangladesh.

Post-partum care in Egypt

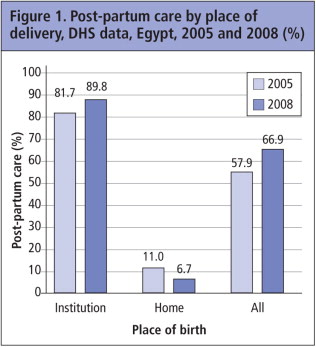

shows the changes in post-partum care in Egypt between 2005 and 2008 by place of delivery. Women giving birth in a health institution reported very high levels of care after delivery, increasing over the two periods to almost 90%. In marked contrast, only a small fraction of women delivering outside a health institution received post-partum care, with coverage decreasing significantly between the two surveys. Overall, post-partum care increased nearly 16% between 2005 and 2008 and was provided to two-thirds of the women surveyed. These figures hide big differentials, however, e.g. post-partum care in 2008 was 81% among urban women vs. under 60% among rural women, and in Upper Egypt only 42% of rural women. Similarly, 91% of the richest women received this care but only 43% of the poorest.

Timing of post-partum care

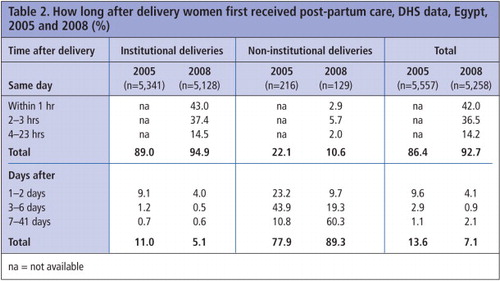

In 2005, nearly 90% of post-partum care among women delivering in health facilities was provided the same day as delivery, while only 22% of those delivering at home received it on the same day (Table 2). More in-depth information available for 2008 showed that nearly half of the 95% of women with institutional deliveries receiving post-partum care the same day said it was within the first hour after birth. Among women delivering at home, there was a marked shift away from care in the first 24 hours towards later care: the percentage receiving post-partum care the same day was halved, but between 7 and 41 days post-partum it increased from 11% to 60% of women surveyed.

If the first hour after delivery had been excluded from this analysis, more than 40% of institution-based post-partum care in Egypt in 2008 would have been left out. Equally importantly, care received after discharge only contributed about 1% of all the care received in institutional deliveries in Egypt (data not shown). In addition, 43% of the small amount of post-partum and post-natal care received after discharge in Egypt occurred 42 days or more after the birth and thus was not included in the analysis.

Cadre providing post-partum care

As expected, the vast majority of post-partum care for women delivering at a health facility was provided by a doctor or a trained nurse-midwife, and hardly any unskilled traditional birth attendants (TBAs) (for only two women in 2005 and one in 2008), and in both surveys these few TBAs had provided the care after discharge. For home deliveries, 13% of care was provided by TBAs in 2005; this fell to only 5% in 2008 (data not shown).

Post-natal care in Egypt

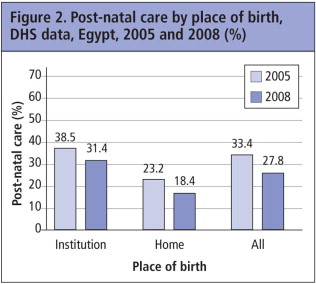

In contrast to post-partum care, there was less post-natal care for newborns in Egypt after both institutional and home deliveries, and the levels fell between the two surveys. Care dropped from a third to slightly more than a fourth of all newborns reported in the 2008 survey ().

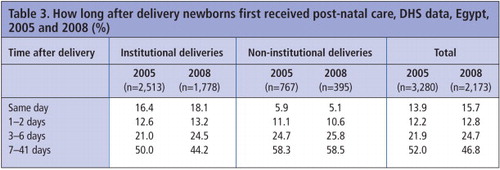

Timing of post-natal care

In 2005, among the infants of women delivering in facilities, only 16% of post-natal care was provided the same day (Table 3). Half of all newborns received care in the 7–41 days post-partum. With home deliveries, same day care was only 6%. By 2008, the situation had not changed much, with 18% of babies born in institutional deliveries receiving care the same day. For home deliveries the situation remained similar.

Cadre providing post-natal care

As expected, all personnel providing post-natal care to newborns following institutional deliveries were skilled providers (mostly doctors) in both 2005 and 2008. Unfortunately the DHS did not ask if it was the same provider as for the woman. Among infants of women delivering at home in the 2005 survey, 84% were skilled providers (doctors, nurses or midwives), while only four providers were described as unskilled. However, 153 mothers (15%) were not able to identify the type of provider. For home deliveries in 2008, all post-natal care providers except five were identified as skilled and only one was not identified (data not shown).

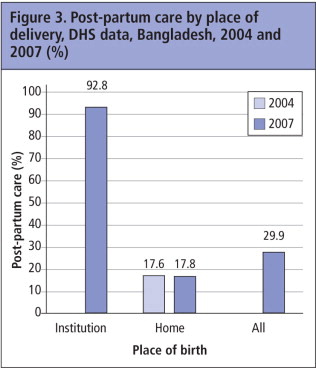

Post-partum care in Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, there were no data on how many women received post-partum care after institutional births in the 2004 DHS (). However, in the 2007 DHS, 93% of women delivering at a health facility received post-partum care. In contrast, less than 20% of women delivering at home received post-partum care in both surveys. Overall, less than a third of all women received post-partum care after their last birth in 2007. Again, big differentials are found, for example, in 2007 45% of urban women vs. 26% of rural women, and 56% of the wealthiest vs. 15% of the poorest received post-partum care.

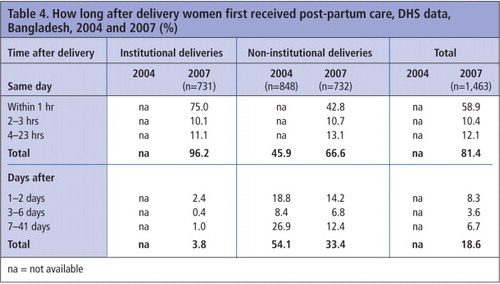

Timing of post-partum care

Again, no data were available from Bangladesh for institutional deliveries in 2004. For home deliveries, 46% of post-partum care was received the same day (Table 4). This rose to two-thirds of women in 2007 (of which about two-thirds was in the first hour). In 2007, 75% of the 96% of institutional deliveries receiving post-partum care the same day had the care in the first hour after birth. For home deliveries, there was a rise in early post-partum care at the expense of care 7–41 days post-partum.

If the first hour after delivery had been excluded from this analysis, more than 78% of the institution-based post-partum care in Bangladesh in 2007 would have been left out.

Cadre providing post-partum care

In 2004 for Bangladesh there were no data on institutional deliveries. In 2007, among the relatively few institutional deliveries, all post-partum care was provided by skilled attendants, such as doctors, nurse/midwives, paramedics, family welfare visitors or medical assistants (data not shown). 48% of post-partum care after home deliveries in 2004 was provided by skilled personnel, dropping to 44% in 2007.

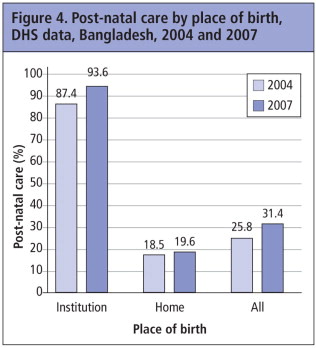

Post-natal care in Bangladesh

Post-natal care in Bangladesh increased slightly between the two surveys for institutional and home births (). Overall, close to a third of newborns in 2007 received post-natal care, a similar percentage as received by their mothers.

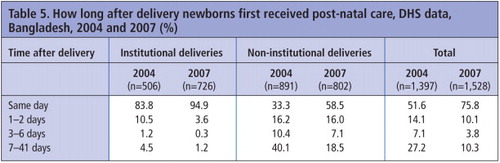

Timing of post-natal care

In 2004, 84% of post-natal care for infants born in facilities took place the same day (Table 5). Among home deliveries, only a third received care the same day. In 2007, 95% of all post-natal care for infants born in facilities was within 24 hours after birth. Though increasing substantially from the previous period, less than 60% of babies born at home first received care the same day. Nearly one in five born at home were first examined 7–41 days post-natally.

Cadre providing post-natal care

In Bangladesh, the picture did not vary between surveys. All (in 2004) or nearly all (96% in 2007) personnel providing post-natal care in facilities were skilled providers, while 55% in 2004 and 47% in 2007 of those providing care after home deliveries were skilled personnel (data not shown).

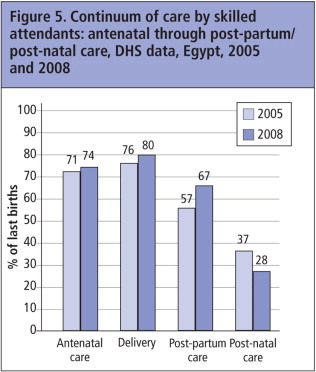

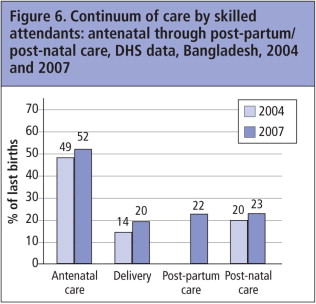

Continuum of care by skilled attendants

and show the proportions (rounded) of’women who received skilled care during pregnancy, childbirth and after their most recent birth, in Egypt and Bangladesh, respectively. Percentages may be lower than with data previously shown because only services provided by skilled attendants are included.

shows an increase in skilled maternity care in Egypt, with antenatal care at 74% in 2008, delivery at 80%, and post-partum care up to 67%. However, post-natal care coverage fell.

In Bangladesh shows that coverage of antenatal care increased slightly but skilled attendance at delivery, while still very low, increased significantly to 20%. Coverage of post-partum care in the 2007 survey was similar to post-natal care, which improved slightly between 2004 and 2007 to reach 23%. The percentages shown here are significantly lower than those shown in and , because only care by skilled attendants is’included.

Trends in timing of care and implications

In many low-resource countries, although there are incentives to increase the number of births occurring in facilities, women and babies are usually discharged’early and little care may be provided afterwards. Hence the importance of knowing with more precision what the first care was and whether further care was received after the first contact. Moreover, given the uncertainties of what constitutes intra-partum vs. post-partum care, including care provided in the first hour after birth, the analyses here may be over-estimating the true coverage, thus conveying a potentially misleading message about the extent of improvement needed in this neglected area (Matthews Mathai, personal communication, June 2011).

In Egypt, the majority of deliveries occurred in health facilities, and in Bangladesh the vast majority of deliveries occurred at home. The resulting post-partum care reflects in part those contexts: two-thirds of women in Egypt had received post-partum care, while less than a third of women in Bangladesh received such care. However, post-natal care seemed’to be less developed in both countries, and had even worsened in Egypt between the two survey periods.Citation18

It is not clear what this apparent drop in neonatal care reflects for Egypt. Given the concerted effort in the last decade to reduce maternal deaths, it may not persist. In the 2008 survey, among all women whose infants received post-natal care, 91% said their newborns had had a blood sample taken from their heels as part of a national programme to assess the level of hepatitis C (data not shown). This intervention, usually done within two weeks of delivery, would have given an opportunity to carry out post-natal care for the baby, which could account for the later start of post-natal care. In any case, the neonatal mortality rate fell from 20 per 1,000 in 2003 to 16 in 2006,Citation29 reflecting the drop in maternal deaths.

For Bangladesh, the picture is also mixed. Despite a 43% increase in deliveries by a skilled attendant, the percentage of women who received antenatal care was far higher than the percentage who delivered with a skilled attendant. At the same time, it is intriguing to note that even in the 2004 survey, the level of post-natal care, at 20%, was higher than that for skilled attendance at delivery (and comparable to the 2007 rates). This seems to indicate, contrary to the Egyptian situation, an increased emphasis on care for the neonate in Bangladesh. Even in the latest survey the post-natal skilled care level is slightly higher than that for delivery. It was, however, encouraging to see that care for the mother and the newborn were at similar levels, which may indicate a policy of caring for them as a dyad, and possibly that care is provided at the same time. Nonetheless, whether or not there is concurrence in the two forms of care represents a gap in our information.

After institutional delivery, there was a trend towards earlier post-partum care in both countries, but especially in Bangladesh. For newborns in Egypt there was not only less post-natal care than for their mothers, but the care was provided much later. For Bangladesh, though coverage figures were lower, there was an increasing effort to provide post-natal care to newborns at an early stage.

After home deliveries, same-day post-partum care halved in Egypt, while it increased importantly in Bangladesh, which may reflect institutional vs. community-oriented policies between the countries. In both countries, post-natal care was provided later after home deliveries than after institutional deliveries (though same day care increased in Bangladesh over time), probably reflecting less access to care and lack of outreach by facilities.

Discussion

Study limitations

Aside from the recall limitations described at the outset, there was also little detail in the questionnaire about who provided post-partum and post-natal care, creating uncertainty as to whether it was provided by a skilled attendant or not. It has previously been shown that women may think they know what the cadre of their attendant was, based on their uniform or roles performed, but this may not be the case, even when the attendant is already known to the woman.Citation19

It has also been suggested that women may not know what care their babies received because they may have been separated for provision of care, especially in the case of complications. However, there are no studies of this. Moreover, there were very low levels of “don't know” or missing values in the datasets. With increasing levels of education and the current practice of keeping newborns with mothers (“rooming-in”), separation and therefore lack of knowledge of what care infants received may be less likely.

It has also been argued that women undergoing caesarean section (c-section) and other surgical procedures may have had diminished recall due to post-operative anaesthetic effects. Additional analysis showed that this was not the case. In Egypt in 2008, 29% of deliveries were by c-section. A comparison of coverage between women with vaginal and caesarean deliveries showed that among women with vaginal deliveries, 31% reported newborn post-natal care compared to 39% of women with c-sections. Similarly, in Bangladesh in 2007, 90% of women with a vaginal delivery at a health institution reported post-natal care for their babies, compared to 97% among those with c-sections. Moreover, the coverage of post-partum care for women with a c-section was the same in both public and private facilities (data not shown). If anything, caesarean sections may have made women more aware of procedures after delivery, rather than less.

When should post-partum and post-natal care start and finish, how frequently should care be provided and how long should it continue?

We have shown that there is uncertainty about when post-partum and post-natal care should start, but we also need to ask in what period of time care should be provided and the number of contacts the mother and newborn should have. A consensus seems to exist in the literature that the period for providing care is from one hour after delivery [of the placenta] up to six weeks.Citation13,14,17,20,21 NICE guidance for the UK extends the care period up to eight weeks.Citation22

Few studies have examined the periods of maximum risk of mortality for the woman and the newborn. In the case of the woman, we know the time by which the main causes of death will set in.Citation5,23 However, guidance is still needed on the critical points of intervention for addressing each cause and minimising its impact.

In the case of neonatal death, a controlled intervention study at the community level pointed to the first 48 hours post-partum as critical for reducing mortality.Citation24 The consensus seems to be that neonatal risks are “…most acute at birth and in the first 48 hours” afterwards.Citation25 Again, however, this information needs to be translated into specific points in time when check-ups and life-saving interventions should be carried out.

There is also scant literature on when subsequent post-partum and post-natal checks should be carried out. The 1998 WHO document suggests the “four sixes” (at six hours, six days, six weeks and six months), with recommendations for “broad lines of care” for the mother and infant in each six-hour period.Citation13 A more recent joint WHO/UNICEF statement recommends at least two home visits within the first three days post-partum (or “as soon as possible after the mother and baby come home” after a facility delivery), and if possible, a third visit before day 7.Citation26 The NICE document sub-divides timing of care into the first 24 hours, days 2–7, and day 8 onwards.Citation22 These recommendations, however, are not derived from evidence of the most effective times for interventions to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity. More work is needed to determine the best timing for such care.

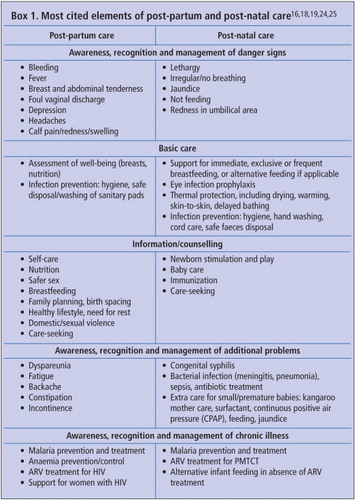

What should post-partum and post-natal care consist of?

Here too there is a lack of specific procedures for care. Unlike with antenatal care, there are no standard protocols or packages of care defining the components and content of post-partum and post-natal care with instructions on what to check in the mother and the newborn at each interval after birth.

There are several guidance documents that describe the elements of care for post-partum women and newborns, either with summary information only or intended mostly for intermediate-level and home care, e.g. the WHO packages of interventions.Citation21 The UK's NICE clinical guideline goes beyond critical danger signs such as haemorrhage, sepsis and tears and into aspects of morbidity such as urinary/faecal incontinence, dyspareunia, breast engorgement and backache in women, and checking baby's thriving, attachment, safety, sleep pattern, and ailments such as thrush, rashes, diarrhoea and constipation.Citation22 A newer publication on key interventions for reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health includes treatment for small and ill babies.Citation26 Box 1 lists the elements of care found in these publications. However, there was no standard set of essential interventions for mothers and newborns – by specific periods – in these publications.

Despite the existence of such lists, surveys such as the DHS have not asked for details of type of care received. However, the 2006 Nepal DHS did include a question about content of post-partum care, and found that 86% of women who said they had received post-partum care also replied positively when asked: “As part of your post-partum care, were you examined for pelvic discharge or normal involution of the uterus or…bleeding?” (Only two women did not answer the question). This implies that women may largely recognize what post-partum care is, albeit from a generic question.

Conclusions and recommendations

This study assesses, for the first time, the levels and a few characteristics of post-partum and post-natal care in two population-based surveys. It confirms what is already widely recognized: that as with skilled attendance at delivery and emergency obstetric care, post-partum and post-natal care continue to be grossly neglected services that lag far behind the high and rising levels of antenatal care women have begun to receive in a growing number of countries.Citation27

This calls for concerted action. Policies should be put in place to ensure that even if a skilled attendant cannot be present at delivery, a specified level and timing of care to be provided promptly after childbirth for both the woman and the newborn should be agreed and recommendations drawn up on how to achieve this, in order to reduce the continuing high levels of intra-partum and post-partum maternal and neonatal mortality. Given the similar pathways to maternal death from abortion complications (e.g. haemorrhage and infection), such policies should obviously also include prompt attendance and management of abortion complications, including at the community level.

The level and competence of the person providing post-partum and/or post-natal care at high-level referral facilities, district or primary level facilities, will of course vary greatly. It may often be the same cadre attending to the needs of both the woman and baby, or in many low-resource countries an untrained person. Thus, it is imperative that medical, nursing and midwifery bodies include in their pre-service curricula the key elements of post-partum and post-natal care, including life-saving skills,Citation28,29 and equally important that countries where there is still a low level of post-partum/post-natal care set up programmes to initiate such care and provide in-service training for existing staff.

In the meantime, surveys such as the DHS should include questions about the type of attendant women are seeing for post-partum care, and whether care for the woman and baby were done at the same time, and the content of that care. They should also find out how soon women were discharged from any facility and continue to ask how much care was received after discharge, so as to clarify how much post-partum and post-natal care are actually being provided.

The World Health Organization is currently in the process of finalising guidelines on what a comprehensive (and minimum) package of post-partum and post-natal care should contain for middle- and low-resource countries, what the care pathways should be, and what data need to be collected. Additionally, they will advise whether one trained provider can safely provide care to both woman and baby, based on what skills are needed. Together, all these efforts will help to design services that will contribute to reducing maternal and neonatal deaths around the world.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the help of Ms Monica Kothari, Health and Nutrition Adviser, ICFI-Macro, who assisted with data tabulations and literature review. Thanks also to Dr Ana Pilar Betrán, Scientist, World Health Organization, who read and commented on an early draft.

References

- BN Simwaka, S Theobald, YP Amekudzi. Meeting Millennium Development Goals 3 and 5. BMJ. 331: 2005; 708–709.

- Countdown Coverage Writing Group. Countdown to 2015 for maternal, newborn, and child survival: the 2008 report on tracking coverage of interventions. Lancet. 371(April): 2008; 1247–1258.

- JE Lawn, ACC Lee, M Kinney. Intrapartum-related deaths: evidence for action. Two million intrapartum-related stillbirths and neonatal deaths: where, why, and what can be done?. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 107: 2009; S5–S19.

- World Health Report 2005. Make Every Mother and Child Count. 2005; WHO: Geneva. At: http://www.who.int/whr/2005/en

- C Ronsmans, WJ Graham, on behalf of Lancet Maternal Survival Series Steering Group. Maternal mortality: who, when, where and why. Lancet. 368(9542): 2006; 1189–1200.

- J Lawn, S Cousens, J Zupan, Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering Team. 4 million neonatal deaths: When? Where? Why?. Lancet. 365(9474): 2005; 1845.

- D Maine. Safe Motherhood Programs: Options and Issues. 1993; Center for Population and Family Health, Columbia University: New York.

- KJ Kerber, J de Graft-Johnson, Z Bhutta. Continuum of care for maternal, newborn, and child health: from slogan to service delivery. Lancet. 370(9595): 2007; 1358–1369.

- Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health. Fact Sheet: RMNCH Continuum of care. At: http://www.who.int/pmnch/about/continuum_of_care/en/index.html. Accessed 24 February 2012.

- Demographic and Health Surveys. At: http://www.measuredhs.com/

- A Fort, M Kothari, N Abderrahim. Post-partum care: levels and determinants in developing countries. DHS Comparative Reports No.15. 2006; Macro International: Calverton MD.

- L Grummer-Strawn, P Stupp. An alternative sampling strategy for obtaining child health data in a reproductive health survey. Population Research and Policy Review. 15(3): 1996; 265–274.

- World Health Organization. Post-partum care of the mother and newborn: a practical guide. Maternal and Newborn Health/Safe Motherhood Unit. Division of Reproductive Health. 1998; WHO: Geneva.

- World Health Organization UNFPA UNICEF World Bank. Integrated management of pregnancy and childbirth. pregnancy, childbirth, post-partum and newborn care: a guide for essential practice. 2006; WHO Department of Making Pregnancy Safer: Geneva.

- World Health Organization. Technical consultation on post-partum and post-natal care. 2010; WHO Department of Making Pregnancy Safer: Geneva. At: whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2010/WHO_MPS_10.03_eng.pdf. Accessed 23 February 2012.

- PS Yoder, M Rosato, R Mahmud. Women's recall of delivery and neonatal care in Bangladesh and Malawi: a study of terms, concepts and survey questions. DHS Qualitative Research Studies No.17. 2010; ICF Macro: Calverton MD.

- WHO/UNICEF. Home visits to the newborn child: a strategy to improve survival. Joint statement. 2009; WHO: Geneva.

- F El-Zanaty, A Way. Egypt Demographic & Health Survey 2008. 2009; Ministry of Health, El-Zanaty and Associates, and Macro International: Cairo.

- J Hussein, V Hundley, J Bell. How do women identify health professionals at birth in Ghana?. Midwifery. 21(1): 2005; 36–43.

- World Health Organization. Post-partum care of the mother and newborn. Report of a Technical Working Group. WHO/RHT/MSM/98.3. 1998; WHO: Geneva.

- World Health Organization. Packages of Interventions for Family Planning, Safe Abortion care, Maternal, Newborn and Child Health. 2010; WHO: Geneva.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Routine postnatal care of women and their babies. National Health Service, NICE Clinical Guideline 37. 2006. London.

- XF Li, JA Fortney, M Kotelchuck. The post-partum period: the key to maternal mortality. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 54(1): 1996; 1–10.

- AH Baqui, A Saifuddin, EA Shams. Effect of timing of first post-natal care home visit on neonatal mortality in Bangladesh: a observational cohort study. BMJ. 339: 2009; b2826.

- K Demott, D Bick, R Norman. Clinical Guidelines And Evidence Review For Post Natal Care: Routine Post Natal Care Of Recently Delivered Women And Their Babies. July. 2006; National Collaborating Centre For Primary Care and Royal College Of General Practitioners: London. At: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG037fullguideline.pdf. Accessed 24 February 2012.

- Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health. A Global Review of the Key Interventions Related to Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (RMNCH). 2011; PMNCH: Geneva.

- C Abou Zahr, M Berer. When pregnancy is over: preventing post-partum deaths and morbidity. M Berer, TKS Ravindran. Safe Motherhood Initiatives: Critical Issues. 2000; Blackwell Science for Reproductive Health Matters: London, 183–187.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Life Saving Skills Manual, Essential Obstetric and Newborn Care. 2006; RCOG Press: London.

- Life-Saving Skills Manual for Midwives. 4th ed., 2008; American College of Nurse-Midwives: Silver Spring MD.