Abstract

Maternal mortality has gained importance in research and policy since the mid-1980s. Thaddeus and Maine recognized early on that timely and adequate treatment for obstetric complications were a major factor in reducing maternal deaths. Their work offered a new approach to examining maternal mortality, using a three-phase framework to understand the gaps in access to adequate management of obstetric emergencies: phase I – delay in deciding to seek care by the woman and/or her family; phase II – delay in reaching an adequate health care facility; and phase III – delay in receiving adequate care at that facility. Recently, efforts have been made to strengthen health systems' ability to identify complications that lead to maternal deaths more rapidly. This article shows that the combination of the “three delays” framework with the maternal “near-miss” approach, and using a range of information-gathering methods, may offer an additional means of recognizing a critical event around childbirth. This approach can be a powerful tool for policymakers and health managers to guarantee the principles of human rights within the context of maternal health care, by highlighting the weaknesses of systems and obstetric services.

Résumé

Depuis la moitié des années 80, la mortalité maternelle a pris de l'importance dans les recherches et les politiques. Thaddeus et Maine ont rapidement compris qu'un traitement ponctuel et adapté des complications obstétricales était un facteur majeur de réduction des décès maternels. Ils ont proposé une nouvelle approche pour examiner la mortalité maternelle, avec un cadre en trois phases pour comprendre les lacunes dans l'accès à une gestion appropriée des urgences obstétricales : phase I – retard dans la décision de demander des soins de la part de la femme et/ou de sa famille ; phase II – retard dans l'arrivée au centre de santé approprié ; et phase III – retard dans l'administration de soins dans ce centre. Récemment, des efforts ont été déployés pour renforcer la capacité des systèmes de santé à identifier plus rapidement les complications qui résultent en décès maternels. Cet article montre que l'association du cadre des « trois retards » et de la méthode dite des catastrophes obstétricales évitées de justesse (« near-miss »), avec l'utilisation d'un éventail de formules de recueil des informations, peut donner des moyens supplémentaires de déceler un événement critique autour de l'accouchement. Cette approche peut constituer un outil puissant permettant aux décideurs et aux administrateurs de la santé de garantir les principes des droits de l'homme dans le contexte des soins de santé maternels, en mettant en lumière les faiblesses des systèmes et des services obstétricaux.

Resumen

Desde mediados de la década de los ochenta, la mortalidad materna ha ido adquiriendo importancia en las áreas de investigación y políticas. Thaddeus y Maine reconocieron temprano que el tratamiento oportuno y adecuado de las complicaciones obstétricas es un factor importante para disminuir las tasas de muertes maternas. Su trabajo ofreció un nuevo enfoque para examinar la mortalidad materna, utilizando un marco de tres fases para entender las brechas en el acceso al manejo adecuado de emergencias obstétricas: fase I – demora por parte de la mujer y/o su familia en decidirse a buscar atención médica; fase II – demora en llegar a una unidad de salud adecuada; y fase III – demora en recibir atención adecuada en esa unidad. Recientemente, se han realizado esfuerzos por fortalecer la capacidad de los sistemas de salud para identificar más rápido las complicaciones que causan muertes maternas. En este artículo se muestra que la combinación del marco de las “tres demoras” con el enfoque del análisis de los “casi errores” y el uso de una variedad de métodos para la recopilación de información, puede ser otro medio de reconocer un evento crítico en torno al parto. Este enfoque puede ser una herramienta eficaz para formuladores de políticas y gerentes de salud para garantizar los principios de los derechos humanos en el contexto de los servicios de salud materna, destacando las debilidades de los sistemas y los servicios obstétricos.

In the mid-1980s, Rosenfield and MaineCitation1 argued that maternal mortality required attention in research and policy. They identified that, as one of the major avoidable cause of deaths for women of reproductive age, maternal mortality had received little attention from health professionals, policymakers or politicians. Subsequently, an advocacy movement for the reduction of maternal mortality led to the World Health Organization (WHO) Safe Motherhood Initiative, launched in Nairobi in 1987.Citation2

This initiative was an effort to draw the world's attention to women's well-being and to deaths occurring around pregnancy and the end of pregnancy. Over the last 25 years, women's health has improved in many countries but global statistics show that the major causes of the vast majority of maternal deaths in developing countries remain the same as 100 years ago, due to direct obstetric causes – haemorrhage, sepsis, complications of abortion, hypertensive disorders, obstructed labour, ruptured uterus and ectopic pregnancy.

Maternal mortality is extremely sensitive to standards of obstetric care.Citation2,3 Reviewing studies on maternal deaths and health service utilization, Thaddeus and MaineCitation4 observed that many pregnant women reach health facilities in such a poor condition that they cannot be saved, and that the time taken to receive adequate care is the key factor in their deaths. From this, the “three delays model” was developed.

Current differences in the maternal mortality ratios (MMR) of high- and low-income countries are usually due to the differences in time management of obstetric complications. Reducing maternal deaths needs not only the improvement of medical assistance for obstetric emergencies in facilities,Citation5,6 but also a reduction in the interval between the onset of a complication and its management in all settings. However, given the relatively low number of maternal deaths in any one geographical area, methodological difficulties have arisen in adopting this approach. This situation has improved since maternal “near-misses” were identified and studied.Citation7,8

This article presents a review and a conceptual discussion of the “three delays” framework based on recent methodological approaches to maternal morbidity and mortality. We did a comprehensive review of the literature on delays in obstetric care from 1980 to 2011 using the keywords: “three delays”, time factors, obstetrics, obstetrical care, patient acceptance of health care, health services accessibility, delivery of health care, quality of health care, maternal mortality, maternal morbidity, pregnancy outcome and related terms on Pubmed, ISI, SciELO, EMBASE, Google Scholar and WHOLIS library. We did not exclude any type of article or language.

The conceptual framework

In 1990, Thaddeus and MaineCitation4 brought about the first shift in the approach to maternal mortality by emphasizing an apparent paradox in public health investments: there is no well-known primary prevention for most obstetric complications leading to death, nor is primary health care able to reduce maternal mortality. They suggested that time – from the onset of a complication to its outcome – must be the single measure used to manage maternal complications.

Studies under the Safe Motherhood InitiativeCitation2 found that there was no association between obstetric complications and any demographic characteristic, behavioural risk factor or antenatal complication.Citation9 Other studies found that no amount of screening could detect women likely to need emergency obstetric careCitation10 nor that improving living conditions reduced maternal mortality.Citation3 Action to reduce maternal mortality had therefore to be designated as secondary prevention.Citation11

While many women who develop complications have one or more detectable risk factors, the majority of women who share these risk factors do not have serious problems. Moreover, in absolute numbers, complications during pregnancy and labour may occur even in the best conditions. A large proportion of serious complications occur among women with no recognizable risk factors at all.Citation1,12

The average interval from onset of a major obstetric complication to death ranges from 2–5.7 hours for post-partum haemorrhage to 3.4–6 days for sepsis.Citation2,13 Thus, the quicker a problem is identified and treated, the greater the chances of stopping the condition from progressing.

Thaddeus and Maine used the concept of “delays” between the onset of a complication and its adequate treatment and outcome to link factors as diverse as distance, women's autonomy and medical assistance. This provides a clear framework for the study of maternal deaths beyond the medical causes by combining in a single framework the social and behavioural causal sequences related to the household, community, and health system, transcending clinical or demographic information.Citation14

The delays are sequential and inter-related: phase I – delay in deciding to seek care by the woman and/or her family; phase II – delay in reaching an adequate health care facility; and phase III – delay in receiving adequate care at that facility. Most maternal deaths cannot be attributed to a single delay; more commonly, a combination of factors lead ultimately to the woman's death.

Phase I

This delay is usually caused by constraints on uptake of health care services, including

“barriers in the socio-cultural milieu that shape values, beliefs and attitudes; in the socioeconomic conditions that shape access to money and information; in the geographical setting that shapes physical accessibility; in the financial environment that determines the cost of services; and in the institutional context that shapes the scope and organization of medical services and the quality of care”.Citation4

Given the complexity of health needs, Rodríguez Villamizar and colleaguesCitation28 added an additional delay for doing maternal mortality surveillance. They made the first delay the recognition of a problem, followed by the opportunity decision to seek care and take action. In Afghanistan, Hirose et al proposed a different sub-division of the phase I delay as the time it takes to decide to seek care and the time it takes to departure for care, which is faster when women have adequate access to care and a supportive social network.Citation20 Therefore, phase I may in fact have three different components: delays in recognition, decision and departure, which reflect the complexity of the problem.

Phase II

The obstacles in reaching a facility may act as a disincentive to seeking care. Even when a woman decides to seek care at an appropriate time, she may face barriers such as lack of transport or long distance to a facility.Citation23

Phase II delay is usually a matter of lack of accessibility to health services. Financial, organizational and sociocultural barriers control the utilization of services.Citation29 Access will be influenced by distribution of health facilities, distance, transport and costs. Women with negative maternal health outcomes travel greater distances, pass through a greater number of facilities and reach an adequate facility later.Citation13

Living in a village or in remote places with no transport available is associated with phase II delays.Citation13,25 Even in developed countries with no transport problems, geographical distance is associated with more frequent negative pregnancy outcomes.Citation30

However, some authors argue that there is no ‘‘urban advantage” as, despite the proximity to services, the urban poor do not have better access to health services than the rural poor.Citation31 Cost and poverty may still play a central role in reaching a facility.Citation15 Many women, due to lack of autonomy or to economic disadvantage, have difficulty funding transport when deciding to seek care.Citation21,25,32

Even when they have money for transport there may be no means of transport availableCitation21 or they have to seek assistance on unsafe roads at night.Citation25 Means of transport used include walking, taking taxis or market trucks, or being carried in a wheelbarrow or hammock on poles.Citation21,25

Reaching an appropriate facility may take from 10 minutes to a full day,Citation25 but usually takes more than one hour.Citation17 Das found that women who reach hospital within four hours of the decision to seek care have a greater chance of a positive outcome than those arriving within eight hours.Citation21

The location of referral also influences the time taken to reach a facility. Women who were referred from home took longer to reach a facility than those referred from a delivery centre.Citation17 The majority of women having hospital-based delivery, especially in African countries, are not referred by a health professional but are self-referrals.Citation25,33 In part, this reflects their lack of confidence in lower level care and results in congestion of hospitals.Citation33 However, even when referred from another facility, either a rural clinic or facility without emergency obstetric care capacity, women arrive in severe clinical condition.Citation25 Reasons for this include structural and process deficiencies – delayed referral, the high cost of emergency obstetric care or lack of public transport.Citation34

The flaws in the referral system lead to patients being shunted from one facility to another,Citation13,33 when facilities are unable to deal with obstetric complicationsCitation35 or they lack trained health professionals. The number of referrals onwards before a woman reaches an appropriate facility influences survival. Therefore, referral guidelines and protocols for the referring and the receiving facility need to be followed, to reduce the disparity between the theoretical hierarchical ‘‘referral pyramid” and actual practice.Citation33

While there may be further factors in delays in reaching a facility, such as lack of a supportive social network,Citation13,16,20,22,32 fundamentally it seems that the real problem in accessing health services is inequity.Citation31

Phase III

The cumulative effect of phase I and II delays contributes to the number of women reaching facilities in a serious condition.Citation25,34,36 Many will never reach a hospital,Citation22,33 and even when they do, treatment may not be successful.Citation1

Other studies have documented additional reasons for inadequate treatment. These include chronic shortages of trained staff and essential supplies,Citation1 the interval between the decision to do emergency surgery and the time of starting the surgery exceeding 30 minutes;Citation37 delays in initiating any adequate treatment following arrival at the facility;Citation35 and shortages of blood products, lack of technical competence among staff and poor attitudes towards patients, caused by shortage of funds.Citation16,18,24,32

Some facilities for comprehensive emergency obstetric care have huge caseloads of women with severe conditions but frequently no clear policies on what adequate treatment for life-threatening conditions should consist of.Citation37 In low-income countries the poor quality of care found even in tertiary facilitiesCitation38 contributes to maternal mortality both directly (due to sub-optimal standards of emergency care) and indirectly (deterring health service utilization).Citation39 The poor quality of services in turn influences women's decision-making and mitigates against timely care.Citation17

Recent utilization of the three-delays framework and the near-miss approach

The three-delays model first appeared in a booklet and a newsletter, and was then published in Social Science & Medicine in 1994.Citation4,12 It has often been used to study the leading causes of maternal mortality from the onset of a complication. A brief analysis of citations of the model indexed in the ISI Web of Science shows an increasing use of this conceptual framework, especially since 2004–2005. A similar increase in the number of publications citing this paper and addressing severe maternal morbidity and maternal near-miss issues has been observed in the same period, indicating concurrent use of both concepts for understanding adverse maternal outcomes.

This increasing interest may in part be a result of another shift in approach to maternal mortality, that is, studies in women who have survived severe complications of pregnancy, either by chance or through receiving timely, adequate hospital care, now known as maternal “near-misses”. This group often share many characteristics with women who have died from obstetric complicationsCitation40,41 – similar pathways and difficulties regarding costs of care, transport and management of complications.Citation15,16,18–20,25,34,35,42,43

Further studies have defined near-misses as an outcome of organ failure, when an important impairment in any organ function appears; the World Health Organization provided an operational definition of this in 2009.Citation8 Near-misses constitute a proxy model for maternal death, giving a larger number of cases for analysis that are more acceptable to individuals and institutions than maternal deaths.Citation7,8,16 Moreover, the women are able to provide information after the event, including the difficulties they faced in reaching timely obstetric treatment,Citation18 information that families of women who died may not be able to provide.Citation15,18,44 Indeed, some authors suggest that information on maternal near-miss events could be key for improving quality of care.Citation19,25

The high number of women arriving in poor clinical condition at referral facilitiesCitation19,34 may be considered as an indicator of the effectiveness of emergency referrals, while the number of near-misses may be an indicator of the performance of obstetric services.Citation34 Therefore, using the three-delays framework with the near-miss approach may enhance monitoring of health system functioning and gaps in obstetric care.

Data collection

Methods for collecting information on delays have ranged from verbal autopsies to in-depth review of a small number of cases, to a more systematic audit of all cases.Citation14,41 Systematic audit is the recommended method for studying maternal deaths, but recent studies of near-miss patients enables greater use of in-depth interviews with the survivors of severe maternal morbidity.

These have proven to be a powerful tool for identifying constraints in medical assistance and understanding how women experience the obstetric care they receive.Citation18 They can also be used for identifying and avoiding sub-standard care factors and analysing the barriers to primary and secondary prevention.Citation43 In short, they give a reasonable quality of information for the evaluation of maternal health programmes and health system functioning.

Interventions based on the framework

Poor recognition of clinical conditions is one of the factors that lead to delay in seeking care. Therefore, some authors have proposed health education for communities and families to help them recognize danger signs in pregnancy of life-threatening conditions, such as ante-partum haemorrhage, post-partum haemorrhage and eclampsia.Citation13,17 However, poor recognition may also happen in a health care facility where the health workers are unable to provide adequate diagnosis and timely referral. Medical education, audit and feedback may improve the ability of medical staff to deal with emergencies. New tools for assessing signs and symptoms of severe maternal morbidity for quick and accurate recognition of severe conditions are being developed.Citation45

Many other interventions are currently being tried to reduce delays but have yet to be evaluated as to whether they can be successfully scaled up and how much they contribute to a reduction in maternal deaths. These include:

on-off payments to cover costs of transport to hospital,Citation32,46

task-shifting policies in which non-physician clinicians are trained to perform a significant proportion of emergency obstetric procedures with similar post-operative outcomes to physicians, as in programmes in Mozambique, Tanzania, Malawi and India,Citation47,48

use of radio-telephones or solar-powered VHF radio communication systems, which have reduced transport delays and improved communication and access to information and advice between, for example, general practitioners and traditional birth attendants, and women patients and health services,Citation49

geographic information systems, designed to work with all types of geographically referenced data, used to trace geographic difficulties in reaching emergency obstetric care,Citation50 and

referral system improvements, such as maternity waiting homes, and the creation of “functional splits” within referral hospitals to improve regional and national referral systems.Citation33,51,52

Further advances in the three-delays theoretical framework

The “Phase Four” delay

Sometimes, surviving a critical condition may lead to further complications or negative consequences for the woman and her family. The likelihood of developing additional severe clinical conditions and even dying some time after the first event are higher compared to the general population.Citation53,54 A woman may suffer from acute or chronic clinical conditions as a consequence of the underlying disease or the interventions that saved her life, such as getting an infectious disease like hepatitis from blood transfusions or surgery, or from continuing obstetric problems. Or she may suffer from psychological problems due to what she has been through.

In addition, the economic burden of emergency hospital care may prevent not only her own return for care for such problems, but her whole family's. Although the improvement of maternal health is a prerequisite for development and poverty reduction, in some settings the survival of a near-miss event may perpetuate poverty. The costs of medical care, transport, drugs and medical supplies may have a huge impact on the household budget for a long period of time.Citation55 The repercussions of surviving severe pregnancy complications have not been thoroughly explored, and further studies are needed.

Limitations of the three-delays model

Although the three-delays model is a widely used framework in maternal death studies, it refers only to emergency obstetric care and does not address missed opportunities for primary prevention or early detection of pregnancy complications during antenatal care.Citation15,56 Although not sufficient, the role of preventive programmes is also very important in preventing and treating maternal morbidity that may or may not cause deaths.Citation1

The fundamental purpose of this theoretical framework aims to draw attention to the gaps in reaching appropriate obstetric care. This is not a linear model; it works only in a retrospective way and does not create the opportunity to improve the care of a specific woman. For a prospective approach, such as a surveillance system to identify and manage factors to prevent a negative outcome, the framework needs rethinking. Even so, improvements in health systems can still be identified and implemented after the fact.

Final considerations

To reduce maternal mortality and near-misses, efforts must reduce the incidence of unwanted pregnancy, the likelihood that a pregnant woman will suffer an avoidable, severe complication of pregnancy or childbirth (e.g. by treating severe anaemia or malaria early in pregnancy or providing safe abortions), and improve the outcomes for women once complications do arise. However, the decline in maternal mortality has been slower than would be expected.Citation57

Thaddeus and Maine's model is a powerful tool but it is an explanatory model and does not provide full comprehension of the phenomenon of maternal deaths. The information on the factors underlying maternal deaths is precious for programmers and health managers so they can change the “road to death”. The use of the three delays framework by maternal mortality committees has been expanded and the gaps in health systems have become more evident.Citation28,35 It improves both the visibility of the problem for managers, shows where responsibilities lie, reveals the lack in provision of necessary sexual and reproductive health care, and encourages the claims of the population for a more equitable society. This is one of the strongest points of this framework, that it shows the gaps in human rights guarantees.

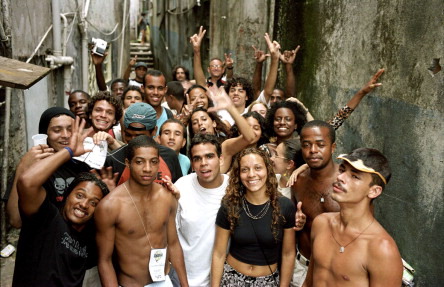

Figure 1 Nos do Cinema group, Favela da Rocinha, Rio de Janeiro, founded to promote social inclusion of youth in low-income neighbourhoods, Brazil, 2003.

But several crucial aspects of this problem are missing. One is the lack of power experienced by women whose general social status is low. Delays may be a result of a dismissive attitude of family members, providers and policymakers and of a political and economic system that puts essential drugs and life-saving equipment out of reach of those who need them. These are human rights violations and a matter of inequity, poverty and gender discrimination.Citation58

The other is the importance of political will and political action. Highlighting the added risk of dying after a woman survives a critical event in pregnancy and the crippling debt some families face whether or not she has survived may contribute to understanding the global neglect of rights in which maternal mortality issues are immersed. However, these will only be seen as human rights violations by society if this information creates social actors who are able to push politicians to show “political will”. Information about the failures of the health system and the guarantee of rights must, somehow, be made the object of public interest which calls for political action.

It is only recently that maternal mortality has been considered by the United Nations as a consequence of violations of key human rights principles, including accountability, equality, non-discrimination and meaningful participation.Citation59 This may force governments to respect national constitutions and international treaties to which they are signatories and take responsibility for guaranteeing basic human rights in defence of safe motherhood. Nonetheless, the practical application of these rights is currently inconsistent, inadequate and even accidental.Citation60

Understanding maternal deaths as a consequence of neglect implies the recognition that it is due to the disadvantaged position of women in society, including with regard to their reproductive rights.Citation61 Only women experience the inherent risks of reproduction; this is a matter of sexual difference. However the lack of appropriate reproductive health care is a matter of gender discrimination, and a consequence of a social system “based on the power of sex and class”. Gender discrimination occurs in all stages of women's lives: preference for boy children, neglect of care for girls, poor access to health, and maternal mortality.Citation62 The death of a woman due to pregnancy complications is not only a biological fact; it is also a political choice that is amenable to change and within human grasp. It depends above all upon political will.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support of CNPq/DECIT National Research Council and Department of Science and Technology, Brazilian Ministry of Health, Grant No. 402702/2008-5, which sponsored the study “Brazilian Network for the Surveillance of Severe Maternal Morbidity”. The theoretical approach described here was developed under the aegis of this study.

References

- A Rosenfield, D Maine. Maternal mortality–a neglected tragedy. Where is the M in MCH?. Lancet. 2(8446): 1985; 83–85.

- D Maine. Safe Motherhood Programs: Options and Issues. 1991; Center for Population and Family Health, Columbia University: New York.

- I Loudon. Obstetric care, social class, and maternal mortality. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Edition). 293(6547): 1986; 606–608.

- S Thaddeus, D Maine. Too Far to Walk: Maternal Mortality in Context. 1990; Center for Population and Family Health, Columbia University School of Public Health: New York.

- A Paxton, D Maine, LP Freedman. Where is the “E” in MCH?. Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health. 48(5): 2003; 373.

- A Paxton, D Maine, L Freedman. The evidence for emergency obstetric care. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 88(2): 2005; 181–193.

- JG Cecatti, JP Souza, MA Parpinelli. Research on severe maternal morbidities and near-misses in Brazil: what we have learned. Reproductive Health Matters. 15(30): 2007; 125–133.

- L Say, JP Souza, R Pattinson. Maternal near miss–towards a standard tool for monitoring quality of maternal health care. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 23(3): 2009; 287–296.

- JP Rooks, NL Weatherby, EK Ernst. Outcomes of care in birth centers. The National Birth Center Study. New England Journal of Medicine. 321(26): 1989; 1804–1811.

- Kasongo Project Team. Antenatal screening for fetopelvic dystocias. A cost-effectiveness approach to the choice of simple indicators for use by auxiliary personnel. Journal of Tropical Medicine & Hygiene. 87(4): 1984; 173–183.

- H Leavell, EG Clark. Preventive medicine for the doctor in his community. 1965; Macgraw Hill: New York.

- S Thaddeus, D Maine. Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Social Sciences & Medicine. 38(8): 1994; 1091–1110.

- BR Ganatra, KJ Coyaji, VN Rao. Too far, too little, too late: a community-based case-control study of maternal mortality in rural west Maharashtra. India. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 76(6): 1998; 591–598.

- HD Kalter, R Salgado, M Babille. Social autopsy for maternal and child deaths: a comprehensive literature review to examine the concept and the development of the method. Population Health Metrics. 9: 2011; 45.

- V Filippi, F Richard, I Lange. Identifying barriers from home to the appropriate hospital through near-miss audits in developing countries. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 23(3): 2009; 389–400.

- P Okong, J Byamugisha, F Mirembe. Audit of severe maternal morbidity in Uganda – implications for quality of obstetric care. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 85(7): 2006; 797–804.

- J Killewo, I Anwar, I Bashir. Perceived delay in healthcare-seeking for episodes of serious illness and its implications for safe motherhood interventions in rural Bangladesh. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition. 24(4): 2006; 403–412.

- JP Souza, JG Cecatti, MA Parpinelli. An emerging “maternal near-miss syndrome”: narratives of women who almost died during pregnancy and childbirth. Birth. 36(2): 2009; 149–158.

- M Roost, C Jonsson, J Liljestrand. Social differentiation and embodied dispositions: a qualitative study of maternal care-seeking behaviour for near-miss morbidity in Bolivia. Reproductive Health. 6: 2009; 13.

- A Hirose, M Borchert, H Niksear. Difficulties leaving home: a cross-sectional study of delays in seeking emergency obstetric care in Herat, Afghanistan. Social Science & Medicine. 73(7): 2011; 1003–1013.

- V Das, S Agrawal, A Agarwal. Consequences of delay in obstetric care for maternal and perinatal outcomes. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 109(1): 2010; 72–73.

- AB Pembe, DP Urassa, E Darj. Qualitative study on maternal referrals in rural Tanzania: decision making and acceptance of referral advice. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 12(2): 2008; 120–131.

- M Cham, J Sundby, S Vangen. Maternal mortality in the rural Gambia, a qualitative study on access to emergency obstetric care. Reproductive Health. 2(1): 2005; 3.

- D Barnes-Josiah, C Myntti, A Augustin. The “three delays” as a framework for examining maternal mortality in Haiti. Social Science & Medicine. 46(8): 1998; 981–993.

- JR Lori, AE Starke. A critical analysis of maternal morbidity and mortality in Liberia. West Africa. Midwifery. 28(1): 2012; 67–72.

- DP Behague, LG Kanhonou, V Filippi. Pierre Bourdieu and transformative agency: a study of how patients in Benin negotiate blame and accountability in the context of severe obstetric events. Sociology of Health & Illness. 30(4): 2008; 489–510.

- M Roost, VC Altamirano, J Liljestrand. Does antenatal care facilitate utilization of emergency obstetric care? A case-referent study of near-miss morbidity in Bolivia. Acta Obstetetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 89(3): 2010; 335–342.

- LA Rodríguez Villamizar, M Ruiz-Rodríguez, ML Jaime García. [Benefits of combining methods to analyze the causes of maternal mortality, Bucaramanga, Colombia]. Panamerican Journal of Public Health. 29(4): 2011; 213–219.

- M Gulliford, J Figueroa-Munoz, M Morgan. What does ‘access to health care’ mean?. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy. 7(3): 2002; 186–188.

- TS Nesbitt, FA Connell, LG Hart. Access to obstetric care in rural areas: effect on birth outcomes. American Journal of Public Health. 80(7): 1990; 814–818.

- Z Matthews, A Channon, S Neal. Examining the “urban advantage” in maternal health care in developing countries. PLoS Medicine. 7(9): 2010

- H Essendi, S Mills, JC Fotso. Barriers to formal emergency obstetric care services' utilization. Journal of Urban Health. 2: 2011; S356–S369.

- SF Murray, SC Pearson. Maternity referral systems in developing countries: current knowledge and future research needs. Social Sciences & Medicine. 62(9): 2006; 2205–2215.

- V Filippi, C Ronsmans, V Gohou. Maternity wards or emergency obstetric rooms? Incidence of near-miss events in African hospitals. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 84(1): 2005; 11–16.

- E Amaral, JP Souza, F Surita. A population-based surveillance study on severe acute maternal morbidity (near-miss) and adverse perinatal outcomes in Campinas, Brazil: the Vigimoma Project. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth. 11: 2011; 9.

- M Rööst, VC Altamirano, J Liljestrand. Priorities in emergency obstetric care in Bolivia–maternal mortality and near-miss morbidity in metropolitan La Paz. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 116(9): 2009; 1210–1217.

- V Gohou, C Ronsmans, L Kacou. Responsiveness to life-threatening obstetric emergencies in two hospitals in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 9(3): 2004; 406–415.

- ML Rosa, VA Hortale. [Avoidable perinatal deaths and obstetric health care structure in the public health care system: a case study in a city in greater metropolitan Rio de Janeiro]. Cadernos de Saude Pública. 16(3): 2000; 773–783.

- CM Pirkle, A Dumont, MV Zunzunegui. Criterion-based clinical audit to assess quality of obstetrical care in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 23(4): 2011; 456–463.

- L Say, R Pattinson, A Gülmezoglu. WHO systematic review of maternal morbidity and mortality: the prevalence of severe acute maternal morbidity (near miss). Reproductive Health. 1(1): 2004; 3.

- RC Pattinson, M Hall. Near misses: a useful adjunct to maternal death enquiries. British Medical Bulletin. 67: 2003; 231–243.

- A Adisasmita, PE Deviany, F Nandiaty. Obstetric near miss and deaths in public and private hospitals in Indonesia. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth. 8: 2008; 10.

- DK Kaye, O Kakaire, MO Osinde. Maternal morbidity and near-miss mortality among women referred for emergency obstetric care in rural Uganda. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 114(1): 2011; 84–85.

- M Jonkers, A Richters, J Zwart. Severe maternal morbidity among immigrant women in the Netherlands: patients' perspectives. Reproductive Health Matters. 19(37): 2011; 144–153.

- JP Souza, JG Cecatti, SM Haddad. The WHO Maternal Near-Miss Approach and the Maternal Severity Index (MSI): validated tools for assessing the management of severe maternal morbidity. Report for the Brazilian National Research Council. 2012

- A De Costa, R Patil, SS Kushwah. Financial incentives to influence maternal mortality in a low-income setting: making available ‘money to transport’ - experiences from Amarpatan, India. Global Health Action. 2009; 2. DOI 10.3402/gha.v2i0.1866.

- D Maine. Detours and shortcuts on the road to maternal mortality reduction. Lancet. 370(9595): 2007; 1380–1382.

- A Gessessew, GA Barnabas, N Prata. Task shifting and sharing in Tigray, Ethiopia, to achieve comprehensive emergency obstetric care. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 113(1): 2011; 28–31.

- AC Noordam, BM Kuepper, J Stekelenburg. Improvement of maternal health services through the use of mobile phones. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 16(5): 2011; 622–626.

- SC Chen, JD Wang, JK Yu. Applying the global positioning system and Google Earth to evaluate the accessibility of birth services for pregnant women in northern Malawi. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. 56(1): 2011; 68–74.

- TF Baskett, CM O'Connell. Maternal critical care in obstetrics. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 31(3): 2009; 218–221.

- P Fournier, A Dumont, C Tourigny. Improved access to comprehensive emergency obstetric care and its effect on institutional maternal mortality in rural Mali. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 87(1): 2009; 30–38.

- V Filippi, R Ganaba, RF Baggaley. Health of women after severe obstetric complications in Burkina Faso: a longitudinal study. Lancet. 370(9595): 2007; 1329–1337.

- RS Camargo, RC Pacagnella, JG Cecatti. Subsequent reproductive outcome in women who have experienced a potentially life-threatening condition or a maternal near-miss during pregnancy. Clinics (São Paulo). 66(8): 2011; 1367–1372.

- J Borghi, K Hanson, CA Acquah. Costs of near-miss obstetric complications for women and their families in Benin and Ghana. Health Policy and Planning. 18(4): 2003; 383–390.

- S Gabrysch, OM Campbell. Still too far to walk: literature review of the determinants of delivery service use. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth. 9: 2009; 34.

- R Lozano, H Wang, KJ Foreman. Progress towards Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5 on maternal and child mortality: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet. 378(9797): 2011; 1139–1165.

- LP Freedman. Using human rights in maternal mortality programs: from analysis to strategy. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 75(1): 2001; 51–60.

- Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Maternal mortality, human rights and accountability. At: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/MaternalmortalityHRandaccountability.aspx2010. . Accessed 28 September 2011.

- Women Deliver. Civil Society Calls for Applying Human Rights-Based Approach to Preventing Maternal Death. At: http://www.womendeliver.org/updates/entry/civil-society-calls-for-applying-human-rights-based-approach-to-preventing-/2011. . Accessed 28 September 2011.

- SG Diniz, AS Chacham. “The cut above” and “the cut below”: the abuse of caesareans and episiotomy in São Paulo, Brazil. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(23): 2004; 100–110.

- FF Fikree, O Pasha. Role of gender in health disparity: the South Asian context. British Medical Journal. 328(7443): 2004; 823–826.