Abstract

This paper reports on a qualitative, exploratory study in 2005, based on interviews with 15 key decision-makers from the Peruvian Ministry of Health responsible for maternal mortality prevention and officials responsible for national data and information on maternal deaths. The main aims were to find out the sources of data and information used by Ministry of Health officials for programme planning and decision-making, whether policies and programmes were informed by the data available, and data flows among central decision-makers within the Ministry and between Ministry and regional and local health centres. Information systems require staff and systems capable of collecting, processing, analysing and sharing data. In Peru, none of these conditions was fulfilled in a homogeneous way. Vertical programmes in the poorest regions had funds for information systems and infrastructure, but limited technical and human resources. Public health workers were overwhelmed with provision of services and not always trained in data collection or informatics. Thus, quality of data collection and analysis varied greatly across regions. Data collection and usage since the study have been improved, reflected in a fall in maternal mortality ratios and women's increased use of maternity services, but efforts to maintain and improve data quality must continue to ensure that initiatives to prevent maternal mortality can be monitored and services improved.

Résumé

Une étude exploratoire qualitative a été menée en 2005, sur la base d'entretiens avec 15 décideurs clés du Ministère péruvien de la Santé chargés de la prévention de la mortalité maternelle et des fonctionnaires responsables des données nationales sur les décès maternels. Il s'agissait de connaître les sources de données utilisées par le Ministère de la Santé pour la planification des programmes et la prise de décision, déterminer si les politiques et les programmes étaient influencés par les données disponibles et connaître les flux de données entre décideurs centraux au sein du Ministère, et entre le Ministère et les centres de santé régionaux et locaux. Les systèmes d'information requièrent du personnel et des mécanismes capables de recueillir, traiter, analyser et partager les données. Au Pérou, aucune de ces conditions n'était remplie de manière homogène. Les programmes verticaux dans les régions les plus pauvres disposaient de fonds pour les systèmes d'information et l'infrastructure, mais leurs ressources humaines et techniques étaient limitées. Les agents de santé publique étaient surchargés par la prestation des services et n'étaient pas toujours formés au recueil des données ou à l'informatique. La qualité du recueil et de l'analyse des données variait donc beaucoup entre régions. Depuis l'étude, une amélioration est intervenue dans le recueil et l'utilisation des données, qui se traduit par une diminution des taux de mortalité maternelle et un recours accru aux services de maternité, mais il faut poursuivre les activités de maintien et de relèvement de la qualité des données pour surveiller les initiatives de prévention de la mortalité maternelle et perfectionner les services.

Resumen

Este artículo informa sobre un estudio exploratorio cualitativo realizado en 2005, basado en entrevistas con 15 autoridades decisorias clave del Ministerio de Salud peruano responsables de la prevención de la mortalidad materna y funcionarios responsables de la información y los datos nacionales sobre las muertes maternas. Los objetivos principales fueron averiguar cuáles son las fuentes de datos e información utilizadas por los funcionarios del Ministerio de Salud para la planificación de programas y la toma de decisiones, si los datos disponibles influían en las políticas y programas y cómo fluyen los datos entre autoridades decisorias centrales en el Ministerio y entre el Ministerio y los centros de salud regionales y locales. Los sistemas de información requieren personal y sistemas capaces de recolectar, procesar, analizar y compartir los datos. En Perú, ninguna de estas condiciones fue satisfecha de manera homogénea. Los programas verticales en las regiones más pobres tenían fondos para los sistemas y la infraestructura de información, pero limitados recursos técnicos y humanos. Los trabajadores de la salud pública estaban agobiadas con la prestación de servicios y no siempre capacitados en la recolección de datos o informática. Por lo tanto, la calidad de la recolección y del análisis de datos variaba mucho entre regiones. Desde el estudio, la recolección y el uso de datos han mejorado, lo cual se refleja en la disminución de las razones de mortalidad materna y en el aumento en el uso de los servicios de maternidad, pero en los esfuerzos por mantener y mejorar la calidad de los datos se debe continuar asegurando que se puedan monitorear las iniciativas para la prevención de la mortalidad materna y mejorar los servicios.

Since the 1980s, when the World Health Organization, the feminist movement and other civil society organizations placed maternal health and mortality on the international agenda, there have been many international and national initiatives to reduce maternal mortality.Citation1 The latest of these was the UN Millennium Development Goals commitment to reduce the maternal mortality ratio by 75% by 2015.

Peru has been involved in these initiatives and, according to Ministry of Health official sources, has reduced its national maternal mortality ratio from 318 deaths per 100,000 live births in 1980 to 298 in 1990Citation2 and 173 in 2000.Citation3 Despite the development of modern data collection methods and information systems, maternal mortality data continue to be based on estimates in Peru, and estimates have been calculated by other national and international institutions, which provide different ratios for these periods. The National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (INEI) reported a maternal mortality ratio of 185 per 100,000 live births for 2000,Citation4 while the UN estimated the ratio to be 410 (ranging from 230 to 590) for the same year,Citation5 and showed that most maternal deaths were concentrated in rural areas and among native populations, including in Apurimac, Amazonas, Huánuco, Cajamarca, Cusco, Madre de Dios, Ayacucho, Huancavelica, and Puno, with ratios ranging from 227 to 361 deaths per 100,000 live births.Citation3

Each of these sources has validity but they use differing methodologies. However, to plan and evaluate health policies and achieve international standards of health, it is essential to have reliable data. In 2005, the question of what data were used for planning health policies in Peru, and how and by whom they were used was unknown. We therefore conducted research to find out which sources of data and information were used by Ministry of Health officials for planning and decision-making at the national level, who provided that information, and how decision-making processes were informed by the data available. We also studied how data and information arrived to and flowed among Ministry of Health decision-makers involved in maternal mortality prevention, and between Ministry of Health and regional/local health centres.

Methodology

This was a qualitative, exploratory study based on a literature review and interviews with a total of 15 key decision-makers from the Peruvian Ministry of Health responsible for maternal mortality prevention programmes and officials responsible for production and/or systematisation of national statistical and epidemiological information on maternal mortality. Most respondents held key positions at the Ministry of Health in 2005 at the time of the research; few of them had been in these positions in the 1990s.

The interviews consisted of open-ended, semi-structured questions. The main areas of inquiry covered how key information was collected and processed and how it was used in the Ministry at national level. We asked: Which Ministry offices collected information? How often was it collected? How did the information flow from health centres to central policy decision-making officials? How was the information processed and shared between offices? Was the information used to develop, implement, monitor and/or evaluate strategies, programmes and budgets for maternal mortality prevention? Were there feedback mechanisms?

Interviews lasted an average of 1.5 hours and took place in Lima. All interviews were recorded and transcribed, and the responses organized thematically and chronologically. The respondents are identified here by their positions at the time of interview but not named.

We also reviewed national policy guidelines, programme and project reports and operational procedures, and academic publications. We covered the six-year period from 1999, when maternal mortality became a target of national surveillance for the Peruvian Directorate of Epidemiology, to 2005 when the interviews were conducted. However, several of our interviewees provided important information regarding mechanisms for data collection in the 1990s, which we report here for their historical perspective. Although we do not discuss information systems per se, we do report the perceptions and experiences of those systems of our interviewees.

Policy researchersCitation6,7 agree that the extent of complete and available information for decision-making determines the rationale for, quality and soundness of problem-setting, policy formulation, analysis, implementation and evaluation. Studies have analysed the inter-relationship between research and action throughout the different stages of knowledge production, dissemination and transfer – as processes that must be shared by researchers and decision-makers in order to be effective.Citation8–11 Researchers and to some extend policy-makers recognize the need for research to inform policy, but there are still few studies dealing with the perspectives and attitudes of policy-makers towards research.Citation12

Our original concern about the use of maternal mortality data took us one step back, to look at the process of data collection and information production as the result of monitoring and evaluating procedures. We felt we could not start from the assumption that the existing research – conceived as a “structured process of collecting, analyzing, synthesizing and interpreting data to answer theoretical questions not visible in the data themselves”Citation11 – had necessarily yielded trustworthy data to begin with.

Maternal health and prevention of maternal mortality initiatives

During the 1990s, the Fujimori administration, in power for more than a decade, implemented a series of neoliberal economic and social reforms common to most Latin American countries in that period. Health sector reform, following guidelines from the World BankCitation13 and other financial institutions, was among them. In Peru this included the establishment of fees for services, a mixed system that prioritized private health insurance, decentralisation of clinic administration, and targeted basic health care packages for specific populations in extreme need.Citation14 Most targeted programmes were supported by international financial institutions and were set up as independent initiatives or projects, with independent consultants, separate from standard services provided by the public health system and the Ministry of Health.

Within this broader picture, there were two different approaches to reproductive health services. In the public health system, there were limited maternity services in the country's health care facilities. At the same time, vertical programmes for family planning and maternal–infant health were being run, focusing only on specific regions and groups living in extreme poverty, and working from a top-down approach. Rural and poor women were among the targeted populations, mainly through three programmes:

National Family Planning Programme (1992–1997) that expanded access to modern contraceptives, but ended up promoting female sterilization during the second half of the decade in ways that violated women's right to make an informed decision;Citation15,16

National Maternal-Perinatal Health Programme (1992–2000), initially a sub-component of the Family Planning Programme, focused on increasing coverage of institutional delivery or home delivery attended by health personnel; and

Basic Health and Nutrition Programme (1994–2000) that initially focused on maternal and child nutrition, and pre- and post-natal care. It emphasized population-level education and prevention initiatives, trained parteras (traditional midwives) in safe and hygienic deliveries and nutrition, but it failed to improve access to basic or emergency obstetric care at health facilities, which continued to be limited.Citation17

In 1995, the Maternal-Perinatal Health Programme launched Proyecto 2000 (1995–2000) with US$60 million from national and USAID funds with the aim of reducing maternal mortality through access to emergency obstetric care; as a result, there was an increase in the quality of care provided and in women's capacity to identify pregnancy and delivery risks. An operational component of training on data collection, processing, and use for managerial and clinic decisions, was also included. While these services and training became available in urban hospitals in 12 of Peru's 24 regions, other regions and rural areas were excluded, and the project continued to prioritize antenatal screening and identification of risk conditions.Citation18

These programmes aimed to be more efficient and achieve better health outcomes by avoiding what was seen as the bureaucratic and deficient public health system, yet the country ended up with two parallel structures that were in fact equally bureaucratic and rigid, which relied on the same pool of local health personnel and technical staff for provision.

By the end of the decade, the limited progress achieved in all three programmes raised national and international concern. The 1996 Demographic & Health Survey (ENDES) had reported a maternal mortality ratio of 265 per 100,000 live births,Citation19 and several new strategies were prepared within the Ministry to combine efforts and unify approaches. The Maternal-Infant Health Insurance (1999), financed by public funds, the World Bank and Interamerican Development Bank, was set up and later merged with the Integrated Health Insurance (SIS) to provide free health services to the poorest. The Maternal Mortality Sentinel Surveillance System (1999) was launched by the Directorate of Epidemiology and the Maternal-Perinatal Programme, aimed to improve the quality and availability of maternal mortality data, and was later extended to register not only deaths but also carry out “risk surveillance”, to improve preventive maternal health care.Citation20

Specific pilot projects continued to address the economic, geographic and cultural barriers to accessing basic and emergency obstetric services in prioritized regions. The FEMME Project was a partnership effort by CARE Peru; the Ministry of Health, through the Ayacucho Regional Health Directorate, the Specialized Maternal-Perinatal Institute, and Ayacucho Regional Hospital from 2000 to 2005. It was a comprehensive intervention designed to improve the organization, management, and operation of obstetrics departments, in order to enhance the quality of emergency obstetric care and to encourage an increase in their utilization.Citation21 Then, in 2001, the Health Reform Support Project (Par Salud)Footnote* was put in place to assist in the modernisation process and the reform of the health system, oriented to reducing maternal and infant mortality and malnutrition in seven regions. Activities have aimed mainly at improving the infrastructure required for maternal mortality prevention and accessibility of basic and emergency obstetric care facilities,Citation22 and developing unified information systems to improve quality of care in selected rural and dispersed populations. By the time we finished our research in 2005, the first part of this project was ending, and evaluation was pending.

Accounting for maternal health and maternal deaths

The 1980s economic and health system crisis had drastically reduced the state's and the health sector's administrative capacityCitation23,24 to collect and systematize information. The Ministry of Health's Office of Statistics & Informatics and Directorate of Epidemiology, had limited financial resources, and staff with few if any qualifications in epidemiology or health data management. With limited formal training and the absence of a career structure, it is not surprising that most of the officials were “hired through political alliances or… moved to the Statistics and Epidemiology Offices instead of being fired” (former staff person, Office of Statistics & Informatics, Ministry of Health).

Official information regarding sexual and reproductive health, including maternal mortality, has been published by the National Institute of Statistics & Informatics every five years from the Demographic & Health Surveys (ENDES), since the first survey took place in 1986. Data include maternal health and maternal mortality indicators at national and regional level, including prevalence of hospital births, prevalence of prenatal care, contraceptive prevalence data, and percentage of births assisted by qualified staff.

ENDES data were collected every five years from a nationally representative sample of 27,843 women aged 15–49 years until 2000, when the sample criteria and process were changed and a shorter version of the survey was developed, to make it possible to collect data every three years, starting with 2004–2006.Footnote* Unfortunately, data from the regional and local levels were no longer representative, given the reduced sample, and there was no longer accurate information about the number of maternal deaths by place of occurrence.Citation25

Additionally, the quality of records of maternal deaths by health centres, local civil registries and parish archives was extremely poor until 1999. Since 1999 the Maternal Mortality Sentinel Surveillance System, launched by the Directorate of Epidemiology and the Maternal-Perinatal Programme, has accounted for each maternal death taking place at health centres, which is immediately notified to the regional epidemiology office and the Ministry of Health.

Deaths taking place outside a medical facility were not recorded by doctors but by police officers or forensic personnel, using different forms and different criteria and procedures. Often a death was registered only if a relative was interested in obtaining a death certificate, which was then filed at the local civil registry office and the data sent up to the National Registry of Identification Office (RENIEC). Studies agree that the use of multiple and varied sources of information is necessary to obtain comprehensive information about maternal mortality.Citation26 Until 2001, however, death records and data from these three sources were not shared among institutions, nor used to obtain a better understanding of the magnitude of maternal deaths (Director of Office of Statistics & Informatics, Ministry of Health).

In 2001, an inter-institutional agreement gave the Office of Statistics & Informatics at the Ministry of Health the responsibility of consolidating information from the three types of forms and systematising national vital statistics; however, by 2005 their budget had been cut to 58.8% of what had been available in 2001,Citation25 making it far more difficult for them to carry out this task adequately.

In addition to practical difficulties, quality of data was also a problem. Forms and certificates lacked any explicit information about a dead person's sex,Footnote† and no standard definitions for the causes of death were used, making it impossible to identify cases of maternal death.Footnote** Furthermore, the National Registry of Identification Office reported in 2005 that 3.5 million people in the country – mostly women living in extreme poverty and in rural areas – were not registered at birth.Citation27 They also estimated that in 2002 they had registered only 55.3% of total deaths.Citation28 The National Registry of Identification Office issues a national identity card, which is required by law to access any public service. Unregistered and rural women in extreme poverty account for the majority of citizens with extremely limited access to health care services. Hence, their deaths accounted for the majority of unregistered deaths, affecting data on maternal deaths.

Operational and managerial issues

The lack of systematic information prior to the first Demographic & Health Survey led the then vertical Family Planning and Maternal--Perinatal Health programmes to collect data separately (in a so-called parallel system) from data collected at public health facilities. In order to monitor progress and whether maternal deaths were declining, these programmes used process indicators such as percentage of births at primary health and emergency obstetric facilities, use of oxytocin, and patient satisfaction, to complement maternal mortality ratios, calculated every five years. They worked independently from other health programmes, and rarely made their information available to them. With political and financial support from the President's Ministerial Council and international donors, however, the Maternal-Perinatal Health Programme was able, for the first time in 1997, to access and consolidate their own data with the data from other health provider institutions within the public health system.Footnote*

Since 2000, the programme has used a Perinatal Information System which has standardized the collection of data on antenatal care, delivery and neonatal care to facilitated decision-making.Citation29 Since 2001, in an effort to better organize the collection and quality of information, the Office of Statistics & Informatics has progressively been centralizing the processing of maternal health and mortality data arriving from local and regional health districts and distributing it to decision-making Directorates. For example, information about diagnostics is fed into the Health Information System (HIS) to inform the Directorate of People's Health (DGSP), and daily movement of medicines and supplies is fed into the Pharmaceuticals Provision System (SISMED) to inform the Directorate of Pharmaceuticals, Medical Supplies and Drugs (DIGEMID).

At the same time, the Integrated Health Insurance Office (SIS)Footnote† began expanding access to maternal health care services and has had its own database and information system (ARFSIS) since 2002, which most interviewees agreed was an accurate record of information about obstetric services provided to the insured population. Monthly information was used to guarantee resources needed for health service provision.

The latest relevant initiative to produce comprehensive health data about maternal health services was developed in 2004 by the Health Reform Support Project, working with the Directorate of Epidemiology and the Office of Statistics & Informatics, to standardize and improve quality of information systems throughout the Ministry. This Project developed an information system that collected data provided by HIS, ARFSIS, and SISMED, to facilitate the analysis and use of data from these different data systems.

Despite all these efforts to build accurate and comprehensive databases to inform decision-making, officials at different levels of seniority within the Ministry of Health still considered it important to collect, directly from the health facility level, information according to their own specific “internal logic of work”, daily decision-making and managerial needs. Nevertheless, they also recognized that because the data on maternal health were to be found in at least seven databases, they had to check all of them too, to obtain a complete and accurate picture, before reaching any decisions (Official, Strategy for Sexual and Reproductive Health; Officer of the Health Promotion and Prevention Directorate; and former Director of Maternal-Infant Programme).

“The information system is still problematic, we need to consolidate the data. The priority in the Directorate of People's Health now is to have trustworthy information for decision-making, because sometimes I want to make a decision and one source says 5, another says 10, and I think it is 11. What should I do? Which is correct? I have to call each Regional Health Directorate and ask: ‘I have X data, is this correct?’ And they might answer: ‘No, I have Y, your data are not right.’ We try to verify before taking decisions. Sometimes when it is urgent and we are asked for data really urgently we have to provide whatever information we have, but we can't guarantee that information if we can't double-check it.” (Official, Directorate of People's Health)

Additionally, the few references to qualitative information and case studies used by Ministry officials were provided by feminist NGOs, civil society organizations, and international agencies participating in the many advisory boards within the Health Ministry.Citation30

Information flows

The Ministry of Health was collecting data from the country's 7,027 primary, secondary and tertiary public health facilities. At the local level, health care providers were filling in multiple forms with patient information, diagnosis, treatment and counselling provided, and pharmaceuticals and medical supplies used. These forms were sent up through the different levels of the health system network until they reached the Ministry of Health.

At each level, Statistics and Epidemiology offices processed the information and consolidated the data, which also moved upwards, all the way to the Statistics & Informatics Office, the Directorate of Epidemiology and other programmes at the Ministry of Health requesting the information. According to the Directorate of Epidemiology, the Sentinel Surveillance Initiative received weekly and monthly reports of any maternal death (or any other disease under epidemiologic surveillance) in the country. After processing and confirming the information, the Directorate of Epidemiology transferred it to the Office for Sexual and Reproductive Health Strategy. However, that Office, which was responsible for the Family Planning and Maternal–Perinatal Health programmes since 2004, also received information from their own parallel information system, which was still active. These latter data were collected by local coordinators at each health facility and moved all the way up to the Sexual and Reproductive Health Strategy Office and to the Statistic & Informatics Office in the Ministry of Health, which processed most of the data.

Limitations of time and limited professional qualifications overwhelmed the health personnel,Footnote* who were filling in over 143 different, non-standardized forms per patient, covering each health programme. There was an absence of advanced information and communications technology, and data processing was taking place at multiple levels, with problems transferring the data upwards at each stage – all combined to produce incomplete and inaccurate information that only arrived at the top from the more isolated geographical regions after two, four or even six months' delay. Limited human and financial resources to process the data after it reached the Office of Statistics & Informatics, among others, thus continued to limit the availability of timely and accurate information for decision-making.

In this panorama, and given that it took place within a tradition of centralized decision-making on policy and programmes, it was not surprising that none of our interviewees or documents reviewed described any information flow process or feedback procedures to move data back down to the local level, which would have allowed those working at the local level to use the data to improve service delivery. Hence, production of policy guidelines and programme planning at the top were prioritized over improvements in programme implementation and service delivery at the local level.

Only brief mentions of the web bulletins posted by the Epidemiology Directorate or to the national meetings with regional coordinators of the Sexual and Reproductive Health Strategy were made when we asked about data return mechanisms.

Use of information by Health Ministry officials for decision-making

Being able to count on trustworthy information and data is important for monitoring trends in national indicators as well as for decision-making at all levels in the policy process – whether to focus on one priority over another, how to design a feasible plan of action and direct resources as needed, or evaluate outcome data on a regular basis.

In the 1990s, national health policy guidelines and priorities in Peru were defined by the President and the President's Ministerial Council, mostly in response to national and international pressure to achieve specific reproductive health goals. This began to change in 2000 when civil society organizations, political parties and government officials met to formulate policy priorities for the National Agreement on the Struggle against Poverty and to develop the National Concerted Health Plan. Despite the policy development process, decisions at the policy level were and continued to be developed and evaluated based on the ENDES (Demographic & Health Survey) data.

All the Ministry officials we interviewed agreed that the ENDES data were the most reliable source of information on health status, and they recalled using mainly these data for identifying health problems and justifying national policy and programme plans during the period of study. Yet the inability of Ministry officials to obtain accurate data from the regional and national level in a timely manner was explained partially by the fact that these surveys were produced only every five years up to 2000, and when they became more frequent were no longer disaggregated so as to be able to identify concrete and urgent needs at local level.

Additionally, the Sisterhood Method used by these surveys has a wide confidence interval and does not provide current estimates for the year of the survey. This limited the capacity to monitor changes in and see any impact of the maternal mortality programme. This survey also tends to under-report early pregnancy deaths, mostly related to unsafe abortion, and in unmarried women or adolescents.Citation26,31

At the operational level, from 1992 Ministry of Health officials began to collect data at local health centres to support operational decisions. Officials at the Sexual and Reproductive Health Strategy Office said their decisions were based mostly on the information they gathered directly from the services provided, using the indicators related to their set priorities (e.g. maternal deaths, antenatal screening, use of oxytocin, hospital births and contraception usage).

Sources of information for decision-making recalled by our interviewees also included their personal knowledge of specific regions and/or populations, their own expertise and intuition gained from prior work experience, and personal contact with other experts.

Despite the lack of reliable information, officials in the Ministry of Health used a top-down approach until 2004, when local initiatives, such as “giving birth in a vertical position” and “maternity waiting homes” have also been acknowledged by Ministry of Health officials and incorporated into national protocols and norms.Citation32

However, mid-level officials did not have responsibility for the allocation of human and financial resources, and could not finance such initiatives themselves. Instead, they had to prepare reports and policy recommendations for Ministry Health Directorates, such as People's Health, Pharmaceuticals, Health Promotion, and Medical Supplies and Drugs, who were able to make these decisions, evaluate the reports and validate the data by comparing them with data from their own sources, before making decisions or allocating funds. Heads of these Directorates had little time to study existing data before deciding upon a particular course of action. The higher they were in the Ministry, according to a former head of the Directorate of People's Health, the less time they tended to have to review existing information, and the more they had to depend on their advisors to summarize it for them.

Thus, there was a disconnect between obtaining accurate, up-to-date information at the operational level and decision-making at the Ministry level, and it was not surprising to find that the Ministry of Health's Planning and Budget Office was relying on historical data to allocate funds to various programmes rather than budgeting on the basis of annually identified needs and up-to-date use of and demand for specific services (former Director of the Planning and Budget Office and former Ministry Advisor). Moreover, with the inconsistencies in the data available, and the steady flow of requests for action arriving to these officials on many different priority issues, it is easy to see why decisions were delayed or postponed, jeopardising efforts to improve the quality and availability of services.

Discussion

Our research provided an understanding of the tensions between demands for evidence-based policy, how data and evidence were actually produced, and whether or not they were used for decision-making. Well-financed vertical programmes funded from abroad during the 1990s were crucial for the recognition of the value of evidence-based policy, accessible up-to-date data and related information, and the development of databases and information systems for policy and operational decision-making. At the same time, the political need to showcase growth and development in Peru motivated an increased interest in accounting for improvements in health status based on specific indicators.

Sources of information were increased, but not in a comprehensive or well-planned manner, and the diversity of information systems created some serious problems. First, the different information systems worked independently from each other, without standard definitions that would have allowed accurate measurement, comparability and merging of data. In many cases, information was duplicated as well. Although there were efforts in the early 2000s to build a more integrated health information system, agree on national indicators, and create more links between government departments, progress was variable.

Information systems require staff capable of collecting and processing the information and basic technical infrastructure to save, transfer, analyse and share the data collected. In Peru, none of these conditions were fulfilled in a homogeneous way. Although vertical programmes in the regions with extreme poverty had funds for information systems and infrastructure, they also had very limited technical and human resources. Health workers were overwhelmed with provision of services and not always trained in data collection or informatics. Thus, conditions for data collection and analysis varied greatly from one region to another.

In addition to these limitations, the political pressure on the public health sector to report positive improvements based on indicators might also explain the poor quality of data collected and the unwillingness to share it. At the operational level, programme officers showed a sense of ownership of the data their offices produced and tended to disregard any other data as inadequate and useless. Moreover, in the context of health sector reforms emphasizing incentives for increased quality of care and productivity,Citation24 outcome data were used to evaluate staff performance and jobs tended to be in jeopardy if goals were not reached.

The upward flow of information described here revealed several structural limitations in the collection and consolidation of data, in spite of the importance of having data available at every level. Conversely, the lack of downward flow of information reflected a lack of understanding of the crucial link between policy formulation and implementation. Thus, decision-makers at the Ministry who we interviewed did not consider it necessary to send data on maternal health and mortality and local performance information to the regional and local health officials in charge of policy implementation and ongoing service provision.

Yet their need to have their own regional and local data, and be able to compare it to data from other regions and nationally – and to have the skills to evaluate and improve the services at their facilities – put the Ministry of Health's decentralization programme, begun in 2005, at risk. While the transfer of functions to regional and local governments did take place, the fragmentation of data and data sources, and the poor quality of local and regional information, would have had an adverse effect on their ability to improve health care provision and resource allocation.

At the national level, the Ministry's decision-makers felt insecure about the policies they recommended due to the unreliability of data and information. They became unwilling to share information openly or to respond to the Congress, the media, civil society, researchers, or the public in general. Not having a unified and reliable data system was one reason why their ability to improve women's access to maternity services was limited.

What has changed since this study?

After 2005, efforts to improve maternal mortality data from both regional and national levels continue. Operational data have mostly been used to evaluate programme performance and fulfilment of goals, such as for MDG5. The Ministry of Health remains concerned to account for maternal mortality with reliable indicators. Since 2006, the Maternal Mortality Sentinel Surveillance System has been accepted by all Ministry offices and directorates as the first and most accurate source of information on numbers of maternal deaths. This not only avoids double counting and delays in collecting information, which arose from using more than one data source, but has given officials more confidence in the data itself.

Beginning in 2007, the Ministry of Health were able to identify clear annual indicators of maternal health service performance and women's demand for family planning to monitor programme goals. In 2008, the Maternal-Infant Programme became one of the five national strategic programmes included in the results-based financingFootnote* mechanism promoted by the Ministry of Finance. This offered the Ministry of Health the opportunity to negotiate the national health budget with the Ministry of Finance, e.g. based on the need for antenatal and emergency obstetric care services, and indicators of health sector performance; and to be accountable for its programme outcomes.Citation33

Initiatives developed by the Statistics & Informatics Office in coordination with each directorate's decision-makers have improved since our study ended. Statisticians who until 2008 worked for the Sexual and Reproductive Health Strategy were hired through the Statistics & Informatics Office to ensure that processing of data and sharing of information would become more fluent and focus on decision-makers' needs. (Follow-up interview with current Statistics & Informatics Office staff, 2012)

An evaluation of Par Salud in 2009 showed a positive impact of its training and infrastructure components, so the project was renewed for ten more years, but results in terms of development and integration of information systems were limited.Citation34

Collaborative initiatives between the Statistics & Informatics Office and the National Civil Registry Office to improve registry and access to National Identification Cards were impeded by changes in priorities and budget allocations. However, in 2011 an agreement for sharing data was signed to facilitate civil registration of women and children at health facilities (Follow-up interview with Statistics & Informatics Office Director, 2012).

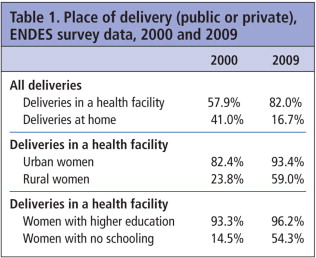

Improvements in data collection and processing on maternal mortality and maternity care, particularly starting after ENDES 2000, have allowed the Ministry of Health to identify, evaluate and prioritize services that contribute to reducing maternal deaths. Improvements between 2000 and 2009 in the proportion of women giving birth in a health care facility illustrate this (Table 1).Citation35

Similarly, a comparison of maternal mortality ratios over three ENDES surveys shows that maternal mortality ratios fell from 265 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in the 1996 survey, to 185 deaths per 100,000 live births in the 2000 survey and to 103 deaths per 100,000 live births in the 2009 survey. Acknowledging that limitations persist, the 2009 survey report states: “In spite of the many sampling errors contained in the estimations for the two [earlier] surveys, it can still be concluded that there has been a decline in maternal deaths, and that the decline has been important.” Citation33

The absence of good quality data for policy and programming partially explains why maternal mortality did not go down as much as might have been expected, given the number of projects aimed at reducing maternal deaths in the years before 2005. However, the combination of far better data, alongside better knowledge of what needs to be done at policy and service delivery level, means that there is a better understanding of the dimensions of maternal health problems, and that initiatives have started showing positive – and measurable – results.

Efforts to maintain and improve data quality must continue to ensure that initiatives to prevent maternal mortality can be monitored and services improved. Efforts to standardize information systems and share data within the Ministry of Health have been extremely important to better identify and quantify women's reproductive and maternal health needs but they have not been enough. Improvements in the information flows within the Ministry and between Ministry and civil society are still needed to ensure availability of services, feedback across the different levels of service provision, support decision-making and allow civil society to assess accountability.

Par Salud and other such projects need to develop collaborative relationships with the Ministry of Health management structures so that the work of these initiatives is integrated into the regular processes of the health sector, to ensure sustainability.

Some Ministry of Health officials still need to acknowledge that existing data on maternal mortality are now available, and at the same time, recognize that estimates related to specific categories of deaths, mostly those from unsafe abortions, adolescent pregnancies and isolated populations, need to be improved greatly.

Lastly, systems and indicators to monitor and improve quality of services and the state of women's health are still needed. Gender and rights approaches should be included in developing such indicators.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the interviewees for giving their time and sharing their knowledge, and the Ford Foundation for financial assistance to conduct the research. A preliminary version of this paper was presented at the Latin American Studies Association Conference, Rio de Janeiro, June 2009. We wish to thank the participants at the panel for their comments.

Notes

* Financed by the Interamerican Development Bank and World Bank loans for an implementation period of ten years.

* ENDES 2004–2006 was collected in a three-year period from a cumulative sample of 19,090 women.

† The person's name was considered enough evidence of sex.

** Only since 2005 has the new death certificate included sex and pregnancy status.

* The Peruvian public health system provides services through three independent institutions: one for employed people with public health insurance; one for the police and armed forces and their closest relatives; and one financed by the Ministry of Health for those who are uninsured. Each kept their own independent maternal death records without any mechanisms to share or gather data.

† The SIS is a decentralized, publicly-funded insurance system covering public health services for the poor population nationwide. See: www.sis.gob.pe.

* Most of these forms were supposed to be filled in by doctors or midwives; however, in most cases nurse-clerks ended up filling in the many forms, along with their other tasks.

* Results-based financing has been defined as “a cash payment or non-monetary transfer made to a national or subnational government, manager, provider, payer or consumer of health services after predefined results have been attained and verified. Payment is conditional on measurable actions being undertaken.” (www.rbfhealth.org). It requires an evidenced-based conceptual framework to identify interventions, and a baseline to monitor progress.

References

- Call to Action, International Conference on Safe Motherhood, Nairobi, 1987; Programme of Action, International Conference on Population and Development, Cairo, 1994; Platform for Action, Fourth World Conference on Women, Beijing, 1995; International Day of Action for Women's Health, 28 May, established 1987, focusing on “Preventing maternal mortality”.

- Ministry of Health. Análisis de la situación de salud del Perú. Informe técnico No2. 1995; General Directorate of Epidemiology: Lima.

- T Watanabe. Tendencia, niveles y estructura de la mortalidad materna en el Perú, 1990–2002. 2002; National Institute of Statistics & Informatics: Lima.

- Peru Demographic & Health Survey - ENDES 2000. 2001; National Institute of Statistics and Informatics: Lima. At: http://www1.inei.gob.pe/biblioineipub/bancopub/Est/Lib0413/Libro.pdf

- World Health Organization. Maternal mortality in 2000: estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA. 2004; WHO: Geneva.

- J Friedman. Planning in the Public Domain. From Knowledge to Action. 1987; Princeton University Press: Princeton NJ.

- C Lindblom. The science of muddling through. Public Administration Review. 19: 1959; 79–88.

- C Weiss. The many meanings of research utilization. Public Administration Review. 39: 1979; 429–431.

- C Almeida. Research of health sector reform policies in Latin America: Regional initiatives and state of the art. 2001; PAHO/WHO-IDRC: Montreal.

- G Walt. How far does research influence policy?. European Journal of Public Health. 4: 1994; 233–235.

- J Trostle, M Bronfman, A Langer. How do researchers influence decision-makers? Case studies of Mexico policies. Health Policy and Planning. 4(2): 1999; 103–114.

- A Hyder, A Corluja, P Winch. National policy-makers speak out: are researchers giving them what they need?. Health Policy and Planning. 26(1): 2011; 73–82.

- World Bank. World Development Report 1993: Investing in Health. 1993; World Bank: Washington DC.

- C Ewig. Global processes, local consequences: gender equity and health sector reform in Peru. Social Politics. 13(3): 2006; 427–455.

- Peruvian Ombudsman Office. Anticoncepción Quirúrgica Voluntaria. Casos Investigados por la Defensoría del Pueblo. Vol.I. 1998; Ombudsman Office: Lima.

- Peruvian Ombudsman Office. La Aplicación de la Anticoncepción Quirúrgica y los Derechos Reproductivos. Casos Investigados por la Defensoría del Pueblo. Vol.II. 1999; Ombudsman Office: Lima.

- A Yamin. Castillos de arena en el camino hacia la modernidad. Una perspectiva desde los derechos humanos sobre el proceso de reforma del sector salud y sus implicancias en la muerte materna. 2003; Centro de la Mujer Peruana Flora Tristán: Lima.

- J Seclen, E Jacoby, B Benavides. Efectos de un programa de mejoramiento de la calidad en servicios materno perinatales en el Perú: la experiencia del Proyecto 2000. Revista Brasileira Saùde Materno Infantil. 3(4): 2003; 421–438.

- Peru Demographic & Health Survey - ENDES 1996. 1997; National Institute of Statistics and Informatics: Lima.

- General Directorate of Epidemiology. Maternal mortality in Peru 1997-2000. 2001; Ministry of Health: Lima.

- Ministry of Health. Impact of the FEMME project in reducing maternal mortality and its significance for health policy in Peru. 2006; Ministry of Health: Lima.

- Ministry of Health. National plan to reduce maternal and perinatal mortality 2009–2015. Technical document. 2007; Ministry of Health: Lima.

- J Arroyo. Salud: la reforma silenciosa. 2000; Universidad Cayetano Heredia: Lima.

- O Ugarte, J Monje. Políticas sociales en el Perú: Nuevos aportes equidad y reforma en el sector salud. 2001; Instituto de Estudios Peruanos: Lima, 571–572.

- A Padilla. Relevancia y perspectiva para el desarrollo de los sistemas de información en población y salud sexual y reproductiva en Perú. Revista Peruana Experimental Salud Pública. 24(1): 2007; 67–80.

- C AbouZahr. Measuring maternal mortality: what do we need to know?. M Berer, TKS Ravindran. Safe Motherhood Initiatives: Critical Issues. 1999; Blackwell Science for Reproductive Health Matters: London, 13–23.

- National Registry of Identification Office (RENIEC). Plan nacional de restitución de la identidad documentando a las personas indocumentadas 2005-2009. 2005; RENIEC: Lima.

- National Institute of Statistics and Informatics. Taller de Estadisticas Vitales. Informe final. 2005; National Institute of Statistics and Informatics: Lima.

- Ministry of Health. Avanzando hacia una maternidad segura. 2006; Ministry of Health: Lima.

- J Anderson. Mujeres de Negro. Muerte materna en zonas rurales del Perú. Estudio de casos. 1999; Ministerio de Salud - Proyecto 2000: Lima.

- National Institute of Statistics and Informatics. Cobertura y calidad de los servicios de salud reproductiva y otras variables y su relación con el nivel de la mortalidad materna: 2007. 2007; National Institute of Statistics and Informatics: Lima.

- J Mayca, E Plalacios-Flores, A Medina. Percepciones del personal de salud y la comunidad sobre la adecuación cultural de los servicios materno-perinatales en zonas rurales andinas y amazónicas de la región Huánuco. Revista Peruana de Medicina Experimental y Salud Pública. 26(2): 2009; 145–160. At: http://www.scielo.org.pe/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1726-46342009000200004&lng=es&nrm=iso. Accessed 17 March 2012.

- Congress of Peru. Law 28927. Ley del Presupuesto del Sector Público para el Año Fiscal 2008. 1997; Lima.

- Ministry of Health. Primera Fase del Programa de Apoyo a la Reforma del Sector Salud Par Salud I. Lecciones Aprendidas. 2009; Ministry of Health: Lima.

- Peru Demographic & Health Survey - ENDES 2009. p.166 & 174. At: http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/FR242/FR242.pdf.