Abstract

This paper proposes a new, community-based approach to the measurement of maternal mortality, and presents results from a feasibility study in 2010–11 of that approach in rural Tigray, Ethiopia. The study was implemented in three health posts and one health centre with a total catchment area of approximately 22,000 people. Priests, traditional birth attendants and community-based reproductive health agents were responsible for locating and reporting all births and deaths in their areas and assisted mid-level providers in locating key informants for verbal autopsy. Community-based health workers were trained to report all births and deaths to the local health post, where vital registries were kept. Once a month, each health post compiled a list of all deaths of women aged 12–49, which were registered in government logbooks. Nurses and nurse-midwives were trained to administer verbal autopsies on these deaths, and assign primary cause of death using WHO ICD-10 classifications. The study drew on the theory of task-shifting, shifting the task of cause-of-death attribution from physicians to mid-level providers. It aimed to build a sustainable methodology for maximizing existing local health care infrastructure and human capacity, leading to community-based solutions to improve maternal health. While the approach has not yet been implemented outside the initial study area, the results are promising as regards its feasibility.

Résumé

Cet article propose une nouvelle méthode à assise communautaire de mesure de la mortalité maternelle, et présente les résultats d'une étude de faisabilité de cette méthode menée en 2010–11 dans le Tigray rural, Éthiopie. L'étude s'est déroulée dans trois dispensaires et un centre de santé avec une zone de desserte totale d'environ 22 000 personnes. Des prêtres, des accoucheuses traditionnelles et des agents de santé génésique communautaires recensaient et déclaraient les naissances et les décès dans leur zone et aidaient les prestataires de niveau intermédiaire à trouver les informateurs clés pour l'autopsie verbale. Les agents de santé communautaires ont été formés au signalement des naissances et décès au dispensaire local, où se trouvaient les registres d'état civil. Une fois par mois, chaque dispensaire établissait une liste des décès de femmes âgées de 12 à 49 ans, qui étaient portés sur les registres administratifs. Des infirmières et des sages-femmes ont été formées à gérer les autopsies verbales et à assigner la cause primaire de ces décès à l'aide des classifications CIM-10 de l'OMS. L'étude était fondée sur le principe de la délégation de tâches, en transférant la responsabilité de l'attribution de la cause du décès des médecins aux prestataires de niveau intermédiaire. Elle visait à élaborer une méthodologie durable pour tirer le meilleur parti des infrastructures sanitaires locales et des capacités humaines existantes afin de trouver des solutions à assise communautaire améliorant la santé maternelle. Si cette méthode n'a pas encore été appliquée en dehors de la zone initiale, elle a obtenu des résultats prometteurs du point de vue de la faisabilité.

Resumen

En este artículo se propone una nueva estrategia comunitaria para medir la mortalidad materna y se presentan los resultados de un estudio de la viabilidad de esa estrategia, realizado en 2010–11, en las zonas rurales de Tigray, en Etiopía. El estudio se llevó a cabo en tres puestos de salud y un centro de salud, con una zona total de captación de aproximadamente 22,000 personas. Curas, parteras tradicionales y agentes comunitarios de la salud reproductiva fueron responsables de localizar y reportar todos los nacimientos y las muertes en sus zonas y ayudaron a profesionales de la salud de nivel intermedio a localizar informantes clave para autopsias verbales. Los trabajadores comunitarios de la salud fueron capacitados para reportar todos los nacimientos y las muertes al puesto de salud local, donde se mantenían los registros vitales. Una vez al mes, cada puesto de salud recopilaba una lista de todas las muertes de mujeres de 12 a 49 años de edad, las cuales eran anotadas en los libros de registros gubernamentales. Las enfermeras y enfermeras obstétricas fueron capacitadas para administrar autopsias verbales de estas muertes y asignar la principal causa de muerte según las clasificaciones CIE-10 de la OMS. El estudio se basó en la teoría de reasignación de tareas, para reasignar a profesionales de la salud de nivel intermedio la tarea de atribución de la causa de muerte antes asignada a profesionales médicos. El objetivo fue crear una metodología sostenible para maximizar la infraestructura de servicios de salud y la capacidad humana, con el fin de producir soluciones comunitarias para mejorar la salud materna. Aunque la estrategia aún no ha sido aplicada fuera de la región inicial del estudio, los resultados con relación a su viabilidad son prometedores.

Globally an estimated 358,000 women die each year from complications of pregnancy and childbirth.Citation1 Despite intensive efforts over the past decade to improve the quality of data collection and attribution of cause of death, no single approach to the measurement of maternal mortality has been shown to be universally successful or feasible. Statistical and analytic approaches alone are not sufficient for the development of targeted interventions to reduce mortality, or for the measurement of progress toward internationally established targets. In the least developed countries, vital registration systems are incomplete or nonexistent, census data collection occurs infrequently, and research-intensive data collection such as population-level household surveys are costly and sporadic. The overall lack of reliable data on maternal mortality at the district or regional level hinders prevention efforts, advocacy, prioritization, and budget allocation.Citation2,3

This paper proposes a new approach to community-based measurement of maternal mortality, and presents results from a feasibility study of that approach conducted in rural Ethiopia.

Measuring maternal mortality

A variety of population-based approaches have been employed to measure maternal mortality, but each has shortcomings. Sentinel surveillance systems, for example, often collect data from relatively small geographic areas, thus generating results that cannot be generalized to a broader population. In addition, sentinel surveillance systems can be costly, and therefore are often short-lived, infrequent, and unable to produce reliable longitudinal data or permit disaggregation of data by local areas or high-risk population groups.Citation4 Census data, while available even for extremely low-resource settings, have proven unreliable in the estimation of maternal mortality ratios.Citation5 Reproductive age mortality studies (RAMOS) represented a major step forward in measurement of maternal mortality,Citation6 but are contingent upon the availability of vital registration systems to ascertain deaths of women of reproductive age.Citation7 Where such data are not widely available, RAMOS alone has not been a feasible method for acquiring complete maternal mortality data, particularly for events occurring outside facilities.Citation8

WHO advises countries to prioritize the development of vital registration programmes.Citation9 Vital registration has, however, been most successful in settings in which the majority of vital events occur in health facilities equipped to capture this information, or in settings where mechanisms exist for linking vital events at the institutional level with those at the community level.Citation10 Settings where health systems infrastructure is weak tend to be the same settings where births and deaths most often occur at home. Vital registration systems in such contexts can miss a significant proportion of vital events, including the large majority of maternal deaths.Citation5,11 In order to improve upon the measurement of births and deaths in low-resource settings, stronger, more comprehensive, vital registration systems are needed to link vital events at both the community and facility levels.Citation12 The development of such systems on a global scale will necessitate reliance upon existing health infrastructures, and will require the involvement of low and mid-level health providers and community members in the collection of vital events data.Citation13,14

In addition to improved data collection systems, there is an increasing need to quantify the global percentage of maternal mortality resulting from each of the major obstetric causes.Citation15 It has been shown repeatedly and in multiple contexts that the steepest reductions in maternal mortality occur when interventions target individual obstetric causes of maternal death (haemorrhage, hypertensive disorders, sepsis, abortion, obstructed labour, ectopic pregnancy, and embolism).Citation2,15,16 Successful targeting of such interventions on the local or national scale requires accurate measurement of cause-specific maternal mortality.

Recent, empirical approaches to measuring maternal mortality have proven successful at the community level. Strategies which rely on key informants who prospectively document all births and deaths in their communities, have been found to be effective in rural, resource-poor settings, and represent a promising technique where surveys and more costly sentinel surveillance techniques are not feasible or sustainable.Citation14

Verbal autopsy is a widely used, indirect method for determining cause of death in the absence of medical certification, which involves in-depth interviews with relatives (and community members) of the deceased.Citation17 While not a new technique, the importance of verbal autopsy for the identification of cause of death in low-resource settings has been reaffirmed with new tools and the development of computer-based algorithms for maternal death as well as other causes.Citation17–19

Study setting

In 2008, the adjusted maternal mortality ratio (MMR) for Ethiopia was 470 per 100,000 live births.Citation1 However, accurate, reliable data on the levels, trends and differentials in maternal mortality for regional and district levels are sorely needed. Without such data, policies and programmes will continue to be implemented without clear evidence to indicate which interventions have the greatest potential for impact.

Tigray, the northernmost region of the country has a population of over four million people, with 81% living in rural areas and 96% identified as Orthodox Christian.Citation20,21 Under the four facility tiers of the Ethiopian national health care system (referral hospital, zonal/district hospital, health centre, and health post) the Tigray Health Bureau maintains one referral hospital, 12 zonal/district hospitals, 38 health centres and 600 health posts.Citation21 As of 2010, the Tigray Health Bureau employed 84 midwives and 1,258 health extension workers (a cadre of female health workers who have been trained to provide basic curative and preventive health services in rural communities).Citation22,23

Methods

In order to address the need for improved data collection methods in a resource-limited setting, we developed a community-based, mixed-methods approach for civil vital registration and accurate measurement of maternal mortality and distribution by cause of death. A feasibility study was conducted in Tigray, Ethiopia, from August 2010 to August 2011. The methodology employed a similar approach to that of the recently tested, community-based, informant approaches in India,Citation14 but with the specific intent of testing the feasibility of collecting cause-of-death data using mid-level providers. While both lay interviewers and mid-level providers have conducted verbal autopsy interviews successfully,Citation2,17 to our knowledge ours is the first study to assess the feasibility of mid-level providers attributing cause of maternal death using verbal autopsy.

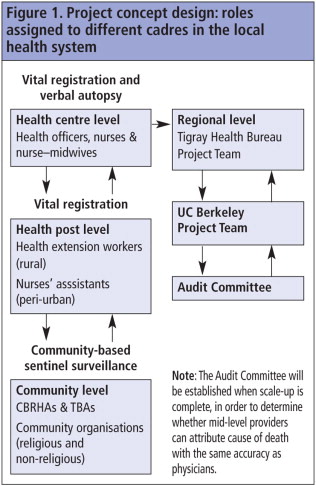

The project took into consideration human resources capacity, local health care infrastructure and potential for sustainability. In the absence of a functional vital registration system for events that occurred outside of health facilities, an active surveillance system was devised for the identification of births and deaths. Because of concerns relating to the sustainability of already existing methodologies, the cost of this new approach was a serious consideration. Consequently, the system we developed, depicted in , relied on the contributions of various community agents for whom a level of involvement in vital events in the community was already a part of their work and responsibilities. Our system formalized these roles through training and active links to the formal health care system.

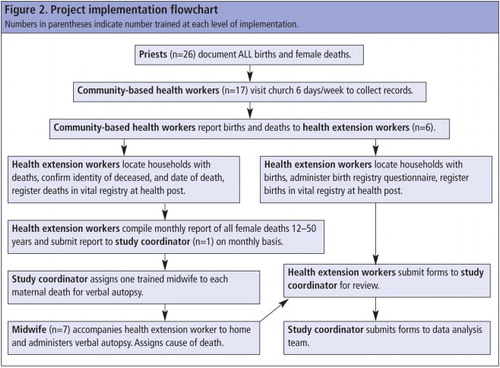

The pilot project was implemented in three health posts (basic, community-level health care facilities) and one health centre (intermediate-level health care facility) with a total catchment area of approximately 22,000 people. In order to raise community awareness about the project plan and rationale, meetings were held before project initiation between all levels of the research team and community leaders, community members, and religious leaders. It was recognized in these meetings that the head priest of each community held an important role in the unofficial registration of births and deaths, and should therefore be integrated into the official registration process as well. shows the project implementation flowchart.

Types of data collection included

Community-based sentinel surveillance

Priests, traditional birth attendants and community-based reproductive health agents were responsible for locating and reporting all births and deaths in their designated areas. They were given detailed training on how to educate and motivate families to report births and deaths in their homes. They also assisted mid-level providers in locating key informants for verbal autopsy and for the verification of births and stillbirths. The data collection tool used at this level was a simple log-book, with columns for the identification of household location with vital events.

Vital registration at health post level

To ensure that all vital events were captured, community-based health workers were trained to report all births and deaths to the local health post (one per village) where vital registries were kept up to date. Once a month, each of the three health posts compiled a list of all births, stillbirths and deaths of females (aged 12 to 49) for verbal autopsy and verification by mid-level providers. The vital events were registered in government-provided logbooks and distributed to health posts.

Vital registration and verbal autopsy

The verbal autopsy survey instrument was field-tested in the Tigrinya language, and adapted to cultural and language norms based on suggestions received during pilot training. Cause-of-death assignment followed the four main stages of the verbal autopsy process: (1) identify cause of death, (2) certify death, (3) code cause of death, (4) select underlying cause of death.Citation19 For all deaths of females aged 12–49 that occurred in the community, one trained mid-level provider (nurse or nurse-midwife) was assigned to conduct verbal autopsies. She interviewed two different adults related to the deceased (the closest living male relative and the closest living female relative) in private. These interviews occurred after the traditional 14-day mourning period, and after informed consent was obtained. Upon completion of the interviews, she reviewed the answers given by both respondents to identify the cause of death. She then certified the death by recording the circumstances and contributing factors on the verbal autopsy form. She then determined if the death was a maternal death, and if so, using the ICD-10 codebook provided to each midwife, recorded the code associated with the cause of death. Finally, using the WHO flowchart for assignment of cause of death from ICD-10 codes, she assigned an underlying cause of death. If the two interviews yielded conflicting information, she would arrange an interview with a third key informant. Verification of births and stillbirths was conducted using a specifically created questionnaire.

Facility-level data continued to be collected, and mid-level providers continued to register all deaths and births that occurred in the facility. All records of maternal deaths in facilities underwent a routine maternal death audit and were double-checked with the vital registration logs at the appropriate health post.

Training

In July 2010, seven mid-level providers (one health officer and six nurse-midwives) and 20 lay health providers (traditional birth attendants and community-based reproductive health agents) received three weeks of intensive training in sentinel surveillance, vital registration, and verbal autopsy.

Traditional birth attendants, community-based reproductive health agents and local priests received five days of intensive training in study protocol, as well as targeted training in sentinel surveillance methodology. As a part of the sentinel surveillance training, small teams of priests and community-based health workers (‘community teams’) from the same communities created maps of their catchment area and groups of households were assigned to each member of the team. The members of the team established a location and time for weekly meetings to collect all data on births and deaths in the community. One member of the team was nominated to notify the health post on a weekly basis of all vital events in the catchment area.

Health extension workers received five days of intensive training, including comprehensive background information and training in the study protocol, sentinel surveillance methodology, and data collection and management for civil vital registration. The process was that they would receive information from the community teams working in sentinel surveillance and register all births and deaths in the catchment area in government-published vital registration logbooks of their health post.

Nurses and nurse-midwives received seven days of training in study protocol, in-depth interview techniques, verbal autopsy techniques with an emphasis on maternal death, and techniques for addressing sensitive subjects. They engaged in role-play activities using the actual verbal autopsy survey instrument, and familiarized themselves with skip patterns for both open- and closed-ended question formats. In addition, they received four days of intensive training in cause-of-death attribution from verbal autopsy, using WHO recommendations of “classification of single causes of death and any of the combinations of the single causes”.Citation24 The minimum list of single causes included: (i) induced abortion and sepsis; (ii) induced abortion and haemorrhage; (iii) ectopic pregnancy (O00); (iv) abortion (O03–O07); (v) antepartum haemorrhage (O67); (vi) post-partum haemorrhage (O72); (vii) sepsis (O85–O86); (viii) eclampsia (O15); and (ix) prolonged labour (O63–O66). We used the International Classification of Diseases 10 (ICD-10) definition of an indirect obstetric death as a death “resulting from previous existing disease that developed during pregnancy and which was not due to direct obstetric causes, but was aggravated by physiologic effects of pregnancy”.Citation24,25 However, separate categories were created for the classification of diseases of local importance, which are associated with a relatively large proportion of maternal deaths, such as hepatitis, malaria, TB, anaemia, heart disease, AIDS, tetanus, and injuries (intentional and unintentional).

Following on from the initial meetings with the communities involved, meetings were held on a monthly basis for the first three months of the study to encourage active participation from community members, and again at the end of the study period. All research team members, medical staff, community health workers and priests involved in data triangulation, as well as other community-based groups, were invited to participate. Broad-based participation was considered crucial for both the acceptance and uptake of the project by community members and for the validation of data by members of the community. The success of our approach relied on community engagement, improved collaboration, and consistent communication between communities and the health care system.

Review of outcomes

All of the personnel engaged in the various project components collaborated well and followed the procedures of the study protocol. Monitoring data show that the expected meetings for data triangulation were held, as well as the births and deaths verification and administration of verbal autopsies. While no formal audit committee process was undertaken in this feasibility study to compare cause of death assigned by mid-level providers to that of gynaecologists, after completion of verbal autopsies for maternal deaths, the forms were reviewed by an obstetrician-gynaecologist, who agreed with all four cause-of-death assignments.

Training of mid-level providers to administer a verbal autopsy questionnaire and attribute cause of death was found to be effective. The responses to the verbal autopsy questions were reviewed by an obstetrician-gynaecologist and the causes of maternal deaths attributed by the nurse-midwives were in accordance with his own analysis.

Community health workers participated in monthly dialogues to review circumstances of death captured in the verbal autopsies. These dialogues successfully illuminated the factors that could have played a role in the maternal deaths – without assigning blame or identifying the deceased person or the key informants by name.

Data collected

During the 12 months of the project, 856 births and 164 deaths were reported, of which 24 of the deaths were in women aged 12–49. Forty-eight verbal autopsies were conducted, in which four of the 24 deaths were identified as maternal. All four assigned post-partum haemorrhage as the cause of death. Causes of death for the other 20 deaths of women of reproductive age were recorded as non-maternal, and a full verbal autopsy was not conducted. Of the 20, four had reached the health centre where the cause of death was recorded in the facility's records as due to malaria (three cases) and tuberculosis (one case).

Data collected through the study estimated a crude birth rate of 39.7 births/1,000 population; an annual all-cause mortality rate of 7.6 deaths/1,000 population; an annual mortality rate for women of reproductive age of 2.8/1,000; and a maternal mortality ratio of 467/100,000 live births. These data were compared to the 2007 Ethiopian National Census data for the Tigray region, which reported an annual crude birth rate of 30.9/1,000; an annual all-cause mortality rate of 9/1,000; and an annual mortality rate for women of reproductive age of 6.3/1,000. The most recent maternal mortality ratio for Ethiopia (2008), estimated by WHO, was 450/100,000 live births.Citation1 Overall, the vital statistics collected within this feasibility study were comparable to vital statistics from the 2007 census, validating the likely accuracy of our findings. It is important to note that the reproductive age mortality rate is slightly lower than what was captured by the 2007 census; however, the census was conducted four years prior to our study, and no adjustments for changes in mortality rates were made.

Cost

If successful when it is scaled up, this approach has the potential to be more cost-effective than existing systems for the measurement of vital events and maternal mortality in a low-resource setting. It is not, however, easy to implement. Recruitment, training, health care worker buy-in, and community acceptance of the project, all must be successfully achieved before a scaled-up version of the project is feasible. The cost of implementation of the feasibility study was approximately US$0.90 per resident of the catchment area, not including project development. This amount was slightly higher than that for a 2002 sentinel surveillance project in Ethiopia at US$0.80 per surveyed person.Citation26 Rising costs and inflation in the intervening years may account for some of the difference. However, most of the costs of the feasibility study were training costs, and with economies of scale, costs would likely be lowered. The World Bank estimated expected expenditures for health information systems on average to be US$0.53 – $2.99 per capita, according to level of development of the country.Citation27 For the vital events surveillance sub-component, the estimates were US$0.05 -$0.20 per capita.Citation27 Our approach, if brought to scale, would require a level of training-related costs similar to those expended in the feasibility study, but would encompass a far larger population; bringing the cost per capita near the World Bank estimated range. It is necessary to recognize, however, that expansion of our system to scale requires political will at both the local and national level.

Discussion

The methodology we have tested for the collection of vital data with cause of death for maternal deaths fills a much-articulated need for improved methods of community-based data collection for maternal mortality.Citation8,12,24,28 Drawing upon existing human resources and health infrastructure, our methodology would establish an on-going, community-based, vital registration system for measurement of cause-of-death data into the local health system. Our approach avoids the shortcomings of other measurement techniques, which can be episodic and resource-intensive, and often yield only cross-sectional or cohort-specific data.

Although over 40% of urban Ethiopian women deliver in a health facility, only 2.4% of rural women do so.Citation20 In a country where the vast majority of the population live in rural areas, facility-based data on maternal deaths are likely to differ systematically from data collected at the community level.Citation19 A variety of approaches exist for assigning cause of death through verbal autopsy,Citation19,29,30 but physician-certified reviewCitation31,32 is considered the “gold standard” by many. However, relying on doctors to review verbal autopsy results is prohibitively expensive in low-resource settings,Citation32,33 and an inefficient use of scarce human resources as it diverts them from their clinical duties.

Our proposal drew on the theory of task shifting,Citation34,35 and applied it to this new domain. Our study design trained mid-level providers to conduct verbal autopsy interviews and shifted the task of cause-of-death assignment from physicians to mid-level providers (nurses and nurse-midwives). This process, when implemented in a larger study, will allow for comparison with physician review. While both lay interviewers and mid-level providers have conducted verbal autopsy interviews successfully,Citation17 using mid-level providers as interviewers allows for the use of a more sophisticated medical classification of cause of death. Moreover, by interviewing at least two respondents, our methodology improves the likelihood of obtaining reliable information of the events leading to a death.Citation29

While this approach has not yet been implemented outside of the initial study, we believe that the results are promising as regards its feasibility. Mid-level providers successfully demonstrated their ability to conduct verbal autopsy interviews and to follow the ICD-10 classification system for cause-of-death assignment. One limitation of the study, however, is that the small sample size (four maternal deaths) does not allow for statistically meaningful assessment of mid-level providers' capacity to accurately determine primary cause of maternal death in comparison with physician-certified review. We hope to conduct future studies of the methodology in larger catchment areas where we anticipate capturing more maternal deaths. In a study powered to assess such outcomes, we would employ an audit committee of obstetrician-gynaecologists to review each completed verbal autopsy, and use tests of inter-rater reliabilityCitation36 to compare cause-of-death attribution by mid-level providers and physicians.

We have attempted to reduce bias by training mid-level providers to use a cause-of-death flowchart based on ICD-10. However, it is possible that the cause of death assigned by mid-level providers may have suffered from interviewer bias due to prior knowledge and understanding of the distribution of cause of death in the catchment area. This potential bias would, however, also apply to physicians assigning cause of death in the same catchment area. We have also attempted to minimize the likelihood of missing deaths related to unsafe abortion by carefully structuring the order and content of the verbal autopsy questionnaire, focusing on strategies to probe key informants on sensitive topics like this in a non-judgemental fashion. Despite such efforts, it is still possible that, because of cultural stigma and/or lack of knowledge on the part of family members, abortion-related deaths may have been under-reported and/or misclassified.Citation26

We are confident that the results from the study reflect the vital events that occurred in the communities where the study was conducted within a reasonable range. All key vital events estimates are within the ranges of expected values for this rural population based on data at the local and sub-regional level from the 2007 Ethiopia census, Tigray report.Citation20

The identification of all births and deaths in their communities by non-salaried, non-health care providers might pose a challenge in the scale-up of our approach. However, wider testing of the approach will show whether this can be mitigated by the continuous engagement of the communities in seeking solutions for improvements in maternal mortality interventions.

Especially in resource-poor settings, reliable morbidity and mortality data are difficult to come by, but are key to developing evidence-based policies in health. In addition to a redoubled global commitment to reducing maternal mortality, data collection systems for measuring maternal mortality must be re-envisioned in order to track progress accurately and efficiently. Data generated by some of the measurement systems currently in use (specifically vital registry, sentinel surveillance, and verbal autopsy) on their own can provide reliable estimates of the levels and differentials of important indicators such as maternal morbidity and mortality, but often put an extraordinary burden on already feeble systems. The system tested in this feasibility project in Ethiopia aimed to build a new, sustainable methodology for the on-going measurement of maternal mortality that has the potential to serve as a blueprint for a low-cost, practical method of measuring vital events, leading to community-based solutions to improve maternal health.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Divya Vohra for her thoughtful contributions to the drafting and revision of the manuscript, as well as Yohanes Tewelde and the Research Team in Tigray, Ethiopia, for their tireless commitment to the health and lives of women in their communities. An oral presentation of a prior version of this paper titled “Maternal mortality at the community level: an innovative approach to measurement” was presented at the Population Association of America Annual Meeting, 2011. Funding for the feasibility study was supported by a grant from the University of California, Berkeley Population Center, Berkeley, USA.

References

- World Health Organization. Trends in Maternal Mortality 1990–2008. 2010; WHO, UNFPA, UNICEF, World Bank: Geneva.

- N Prata, A Sreenivas, C Gerdts. Maternal mortality in developing countries: challenges in scaling-up priority interventions. Future Medicine. 6(2): 2009; 311–327.

- G Lewis. Reviewing maternal deaths and complications to make pregnancy safer. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 22(3): 2008; 447–463.

- G Lewis. Beyond the numbers: reviewing maternal deaths and complications to make pregnancy safer. British Medical Bulletin. 67(1): 2003; 27.

- K Hill, C Stanton. Measuring maternal mortality through the census: rapier or bludgeon?. Journal of Population Research. 28(1): 2011; 31–47.

- P Setel, O Sankoh, C Rao. Sample registration of vital events with verbal autopsy: a renewed commitment to measuring and monitoring vital statistics. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 83(8): 2005; 611–617.

- J Fortney, S Gadalla, S Saleh. Causes of death to women of reproductive age in two developing countries. Population Research and Policy Review. 6(2): 1987; 137–148.

- K Hill, S El Arifeen, M Koenig. How should we measure maternal mortality in the developing world? A comparison of household deaths and sibling history approaches. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 84(3): 2006; 173–180.

- J Geynisman, A Latimer, A Ofosu. Improving maternal mortality reporting at the community level with a 4-question modified reproductive age mortality survey (RAMOS). International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 111(1): 2011; 29–32.

- L Say, D Chou. Better understanding of maternal deaths, the new WHO cause classification system. British Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 118: 2011; 15–17.

- CD Mathers, DM Fat, M Inoue. Counting the dead and what they died from: an assessment of the global status of cause of death data. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 83(3): 2005; 171–177.

- W Graham, L Foster, L Davidson. Measuring progress in reducing maternal mortality. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 22(3): 2008; 425–445.

- C AbouZahr. New estimates of maternal mortality and how to interpret them: choice or confusion?. Reproductive Health Matters. 19(37): 2011; 117–128.

- P Mony, K Sankar, T Thomas. Strengthening of local vital events registration: lessons learnt from a voluntary sector initiative in a district in southern India. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 89(5): 2011; 379–384.

- K Khan, L Say, A Gülmezoglu. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review. Lancet. 367: 2006; 1066–1074.

- M Mwanyangala, H Urassa, JC Rutashobya. Verbal autopsy completion rate and factors associated with undetermined cause of death in a rural resource-poor setting of Tanzania. Population Health Metrics. 9(1): 2011; 41.

- D Chandramohan, G Maude, L Rodrigues. Verbal autopsies for adult deaths - issues in their development and validation. International Journal of Epidemiology. 23(2): 1994; 212–222.

- S Barnett, N Nirmala, T Prasanta. A prospective key informant surveillance system to measure maternal mortality - findings from indigenous populations in Jharkhand and Orissa, India. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 8(6): 2008

- World Health Organization. Verbal Autopsy Standards: ascertaining and attributing causes of death. 2007; WHO: Geneva.

- Central Statistical Agency. Ethiopian National Census. 2007; CSA: Addis Ababa.

- Tigray Health Bureau Profile of 2001 (2009 GC). Mekele. 2010; Tigray Regional Health Bureau: Ethiopia.

- T Alemayehu, K Otsea, A GebreMikael. Abortion care improvements in Tigray, Ethiopia: Using the Safe Abortion Care (SAC) approach to monitor the availability, utilization and quality of services. 2009; Ipas: Chapel Hill, NC.

- K Otsea, S Tesfaye. Monitoring safe abortion care service provision in Tigray, Ethiopia: Report of a baseline assessment in public-sector facilities. 2007; Ipas: Chapel Hill, NC.

- O Campbell, C Ronsmans. Verbal autopsies for maternal deaths: a report of a WHO workshop, London, 10–13 January 1994. 1994; WHO: Geneva.

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision: Instruction Manual. 2nd ed. 2004; WHO: Geneva.

- P Byass, Y Berhane, A Emmelin. The role of demographic surveillance systems (DSS) in assessing the health of communities: an example from rural Ethiopia. Public Health. 116(3): 2002; 145–150.

- D Jamison, J Breman, A Measham. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. Chapter 54. 2006; World Bank, Oxford University Press: Washington DC.

- C Ronsmans, W Graham. Lancet Maternal Survival Series. Maternal survival 1 - Maternal mortality: who, when, where, and why. Lancet. 368(9542): 2006; 1189–2000.

- E Fottrell, P Byass. Verbal autopsy: methods in transition. Epidemiologic Reviews. 32(1): 2010; 38–55.

- C Mathers, T Boerma. Mortality measurement matters: improving data collection and estimation methods for child and adult mortality. PLoS Medicine. 7(4): 2010; e1000265.

- T Evans, S Stansfield. Health information in the new millenium: a gathering storm?. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 81(12): 2003; 856.

- Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2005. 2006; ORC Macro: Addis Ababa, Central Statistical Agency and Calverton, MD.

- R Joshi, A Lopez, S MacMahon. Verbal autopsy coding: are multiple coders better than one?. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 87(1): 2009; 51–57.

- D Chandramohan, L Rodriguez, GH Maude. The validity of verbal autopsies for assessing the causes of institutional maternal death. Studies in Family Planning. 29(4): 1998; 414–422.

- C Murray, A Lopez, D Feehan. Validation of the symptom pattern method for analyzing verbal autopsy data. PLoS Medicine. 4(11): 2007; e327.

- K Gwet. Handbook of Inter-Rater Reliability: the definitive guide to measuring the extent of agreement among raters. 2nd ed. 2010; Advanced Analytics, LLC: Gaithersburg, MD.