Abstract

Progress in reducing maternal mortality has been slow and uneven, including in Latin America, where 23,000 women die each year from preventable causes. This article is about the challenges civil society organizations in Latin America faced in assessing budget transparency on government spending on specific aspects of maternity care, in order to hold them accountable for reducing maternal deaths. The study was carried out by the International Planned Parenthood, Western Hemisphere Region and the International Budget Partnership in five Latin American countries – Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Panama and Peru. It found that only in Peru was most of the information they sought available publicly (from a government website). In the other four countries, none of the information was available publicly, and although it was possible to obtain at least some data from ministry and health system sources, the search process often took a complex course. The data collected in each country were very different, depending not only on the level of budget transparency, but also on the existence and form of government data collection systems. The obstacles that these civil society organizations faced in monitoring national and local budget allocations for maternal health must be addressed through better budgeting modalities on the part of governments. Concrete guidelines are also needed for how governments can better capture data and track local and national progress.

Résumé

Les progrès dans la réduction de la mortalité maternelle ont été lents et inégaux, même en Amérique latine, où 23 000 femmes meurent chaque année de causes évitables. Cet article décrit les obstacles que les organisations de la société civile rencontrent en Amérique latine pour évaluer la transparence des dépenses gouvernementales pour des aspects spécifiques des soins de maternité, afin de les rendre comptables de la réduction des décès maternels. L'étude a été menée par la Fédération internationale pour la planification familiale, région de l'hémisphère occidental, et le Partenariat budgétaire international, dans cinq pays d'Amérique latine : Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Panama et Pérou. Elle a révélé que la plupart des informations recherchées n'étaient disponibles publiquement qu'au Pérou (sur un site Internet du Gouvernement). Dans les quatre autres pays, ces informations n'étaient pas accessibles publiquement et s'il était possible d'obtenir quelques données auprès de sources ministérielles et du système de santé, le processus de recherche était souvent complexe. Les données recueillies dans chaque pays étaient très différentes, en fonction non seulement du niveau de transparence budgétaire, mais aussi de l'existence et de la forme des systèmes gouvernementaux de recueil de données. Les obstacles que ces organisations de la société civile ont rencontrés pour surveiller les allocations budgétaires nationales et locales pour la santé maternelle doivent être levés avec de meilleures modalités budgétaires de la part des autorités. Des directives concrètes sont aussi requises sur les moyens permettant aux gouvernements de mieux collecter des données et suivre les progrès locaux et nationaux.

Resumen

Los avances en la disminución de la mortalidad materna han sido lentos y desiguales, incluso en Latinoamérica, donde cada año mueren 23,000 mujeres por causas evitables. Este artículo trata sobre los retos que las organizaciones de la sociedad civil en Latinoamérica enfrentaron al evaluar la transparencia presupuestaria de los gastos gubernamentales en aspectos específicos de la atención materna, a fin de imputarles la responsabilidad de disminuir las tasas de muertes maternas. El estudio fue realizado por la Federación Internacional de Planificación de la Familia/Región del Hemisferio Occidental e International Budget Partnership, en cinco países latinoamericanos: Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Panamá y Perú. Se encontró que solo en Perú la mayoría de la información que buscaban estaba disponible al público (en un sitio web gubernamental). En los otros cuatro países, ninguna de la información estaba disponible al público y, aunque era posible obtener por lo menos algunos datos del ministerio y sistema de salud, el proceso de búsqueda generalmente tomó un rumbo complejo. Los datos recolectados en cada país fueron muy diferentes, dependiendo no solo del nivel de transparencia presupuestaria, sino también de la existencia y tipo de sistemas gubernamentales para la recolección de datos. Los obstáculos que encontraron estas organizaciones de la sociedad civil para monitorear asignaciones presupuestarias nacionales y locales a la salud materna deben abordarse mediante mejores modalidades presupuestarias por parte de los gobiernos. Además, los gobiernos necesitan directrices concretas sobre la mejor manera de capturar los datos y seguir los avances locales y nacionales.

Addressing unacceptably high levels of maternal mortality has been a cornerstone of global health and development policy since the 1980s. In recent years, the issue has seen a surge of media attention and funding from governments and global health donors. In 2000, governments committed to reducing the maternal mortality ratio by 75% by 2015 as part of Millennium Development Goal 5 (MDG 5).

Progress has been slow and uneven, however, including in Latin America where 23,000 women die each year from preventable causes.Citation1 Globally, progress towards reducing maternal deaths is well short of the 5.5% annual decline needed to meet the MDG targetCitation2 and prevent 358,000 women and girls dying each year, almost all in developing countries.Citation3 In response, the UN launched the Global Strategy for Women's and Children's Health (Global Strategy) in September 2010, garnering member state commitment, particularly from poorer countries, to intensify existing women's and children's health programmes.

While there are many ways to improve maternal health, there is agreement at the global level that ending maternal mortality requires a comprehensive, integrated package of essential interventions and health services, including family planning, safe abortion services, antenatal care, skilled birth attendance, emergency obstetric and post-partum care.Citation4 There is also consensus that governments must have a clear strategy for reducing maternal mortality. This includes the resources to improve services and make them accessible, affordable and of high quality; and the skilled health professionals required for implementation.

With only three years left until the target date for achieving the Millennium Development Goals, assessing and monitoring information on the extent and effectiveness of maternal health investments is crucial, and a task that civil society organizations (CSOs) should be involved in. Why? First, the creation of the Global Strategy has directed additional resources, both from national budgets and multilateral aid, towards maternal, newborn and child health. Second, the Global Strategy establishes mechanisms to hold governments accountable for results and use of resources, which can only be achieved through analysis of transparent public financing. Third, greater information on budget allocations and programmes would allow governments to better track their own expenditures, assess the effectiveness of programmes and ensure that these resources reach their intended recipients.

Challenges to tracking progress

Despite global agreements, ensuring implementation of these strategies and evaluating progress remains a complex challenge in Latin America. One of the main factors is that there is usually no single budget line for sexual and reproductive health that can be followed within national health budgets, much less a specific line for maternal health – even where maternal health programmes and policies exist.

In Latin America, a significant amount of funding for sexual and reproductive health comes from multilateral donors, such as UNFPA and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). These donors have called on governments to improve data collection for maternal health grants they receive,Citation5 to better determine how much aid has been directed to specific interventions within national reproductive health programmes. Even in countries where specific budget lines exist for contraceptives – as is the case in Guatemala and El Salvador – they contain only aggregated data and are not broken down into specific budget lines for other aspects of maternal health, such as medicines or training of personnel.

Similarly, given the vertical nature of global health programmes and funding, national governments and agencies are required to report to multiple stakeholders and to donors that often have different requirements. Perhaps most importantly, health workers are overburdened by excessive data and reporting demands from multiple and often un-coordinated sub-systems.Citation6 These multiple’reporting systems add complexity to health accounts, and contribute to less than optimal analysis and diminished government transparency. As the Health Metric Network describes in its publication Country Health Information Systems: A Review of the Current Situation and Trends, Citation7 although most countries are using indicators and targets to monitor progress on maternal health, the availability and quality of data do not allow them to do so effectively.

These factors all contribute to the complexities governments face in collecting and reporting information, which in turn hinder the ability of CSOs to access accurate and complete data and demand accountability. The International Budget Partnership (IBP) works to build the capacity of civil society to successfully use budget analysis as an advocacy tool. In 2010, the IBP launched the Ask Your Government initiative, a pilot involving 100 CSOs in 86 countries. Participating CSOs requested detailed budget information on specific health and development issues, two of which were related to maternal health. Only 27 out of 84 governments were willing and able to provide some information about their investment in life-saving interventions linked to maternal health, evidencing the difficulties CSOs face in tracking government budgets and spending.Citation8

Measuring budget transparency on maternal health: a pilot study

In recent decades, civil society organizations have been working to better understand and influence government budgets. In recognition of the need for increased capacity to be able to do so effectively among sexual and reproductive health and rights organizations in Latin America, the IPPF/WHR and IBP developed a pilot study that was carried out in 2010 by IBP researchers and IPPF/WHR programme staff. The purpose of the study was to determine the extent to which CSOs in five Latin American countries (Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Panama and Peru) could access and monitor government budgets and spending for maternal health. The study highlighted the challenges CSOs faced in collecting information on government spending for maternity care. Based on the findings, this paper presents recommendations on how information and budgeting systems need to be improved to allow for better monitoring.Footnote*

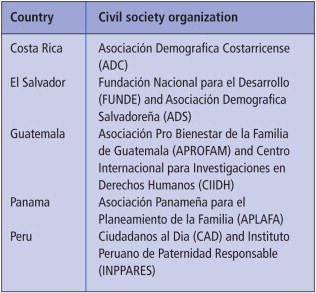

Countries were chosen on the basis of two criteria: that they represented a wide range of maternal mortality ratiosCitation9 and different levels of country budget transparency according to the Open Budget Index developed by the IBP.Citation10 The countries and CSOs chosen were:

Methodology

Although the final goal of information-gathering was to enhance advocacy effectiveness, the main purpose of the case study was the information-gathering process itself. Its aim was to enhance the groups' knowledge of where and how to seek planning and budget information, and with it to assess the level of government accountability related to maternal health.

Even though the search process to gather information varied from country to country, a standard form was used to record each organization's findings. Similarly, organizations followed the same steps to determine whether the government produced and published information about maternal health spending. First, they searched for all available documentation on the websites of national ministries and international agencies such as PAHO for information on their governments' specific policies and commitments related to maternal health, e.g. national strategic plans to reduce maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality.

In all cases, participants were able to find existing policies and programmes designed to reduce maternal mortality and improve reproductive health services. After locating these documents, they then shifted their attention to searching for corresponding budget lines. To ensure consistency and to provide a framework during the information gathering process, it was agreed that they would seek specific budget information in the following categories: Citation11–15

Integrated reproductive health care: budget for contraceptive methods disaggregated by type, and budget for folic acid and iron supplements;

Skilled attendance at delivery: budget for in-service training for health workers (nurses and midwives);

Emergency obstetric care (during and after delivery): budget for supply of essential medicines (uterotonics – oxytocin, misoprostol and ergotamine, saline solution and magnesium sulfate), blood banks, and in some cases investment in manual vacuum aspiration equipment.

The next step was then to look for budget information available on the internet, that is, information on websites of the Ministries of Finance and Health, and other governmental units. If this information was not available on the internet, the CSOs then submitted information requests to the Ministries of Finance and Health in their countries under the auspices of national Freedom of Information Acts.

As a further step, in order to follow up these requests or if they were not answered, they made informal contact with and had meetings with civil servants, which constituted their main sources of information. In general, these meetings were with technical staff within the Ministry of Health, such as staff working in national departments of reproductive health. These contacts then provided the requested information, or requested it from health units or other departments.

To develop a systematic report for each country, participants completed logbooks that described all the information requested and obtained at each step of the process. Lastly, each country team assessed the information gaps they found and analysed how the information available needed to be improved, in order to be able to track public spending on maternal health.

Findings

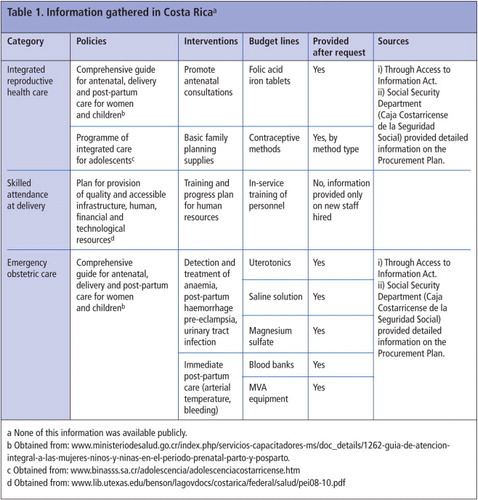

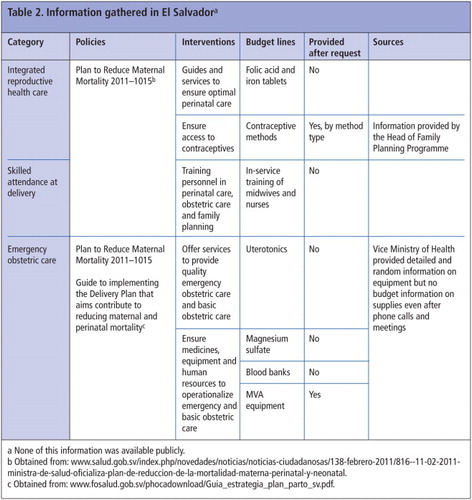

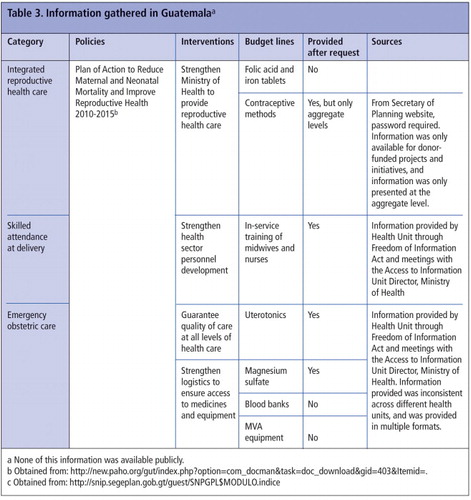

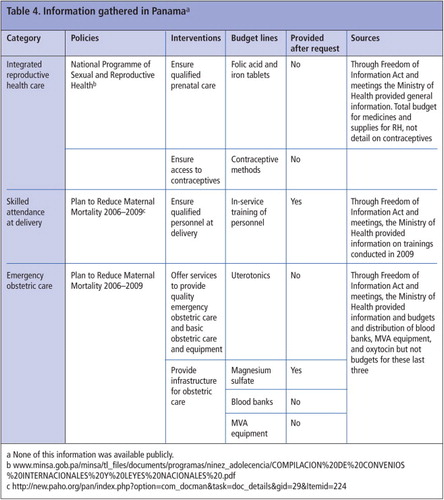

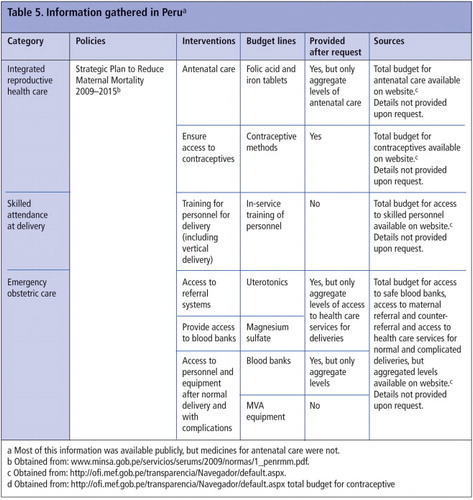

Findings varied depending on the level of transparency and detail of information contained in each government's budgets. CSOs in Costa Rica, Guatemala and Peru obtained substantial policy and budget data directly from their governments' websites. CSOs in El Salvador and Panama were able to gather policy data through external websites but only a limited amount of budget information (see Tables 1–5 for summary findings from each country).

Costa Rica did not have a single programme that addressed maternal mortality, but rather specific plans and guidelines that established government commitments to ensure maternal health care, including access to integrated reproductive health care, skilled personnel and emergency obstetric care during and after pregnancy (Table 1). However, the guidelines, procurement and tools necessary for quality and timely service provision were centralized in a single institution, the Social Security Administration. Each of the health units developed their procurement plan and the Social Security Administration compiled and defined the final procurement plan, which included the budget for all types of contraceptives and medical and equipment supplies. Through Costa Rica's Freedom of Information Act, the CSO identified the Office of Planning for Goods and Services as the appropriate entity from whom to request the information, including items such as equipment for manual vacuum aspiration, uterotonics and contraceptives. The organization filed multiple requests and interviewed the Office director to explain their objectives. As a result, they were able to obtain around 70% of the detailed information requested. The only information they could not obtain was on the budget for training of personnel (the agency in charge of training and professional development for the health sector did not respond to their request).

In El Salvador, the information-gathering process required numerous meetings with Ministry of Health staff, as there was no single person responsible for handling Freedom of Information requests, and clear processes for how to use and enforce the Freedom of Information Act were also lacking. Personal contacts, such as with the Vice Minister, the Head of the Family Planning Programme Unit and the Head of the Integrated Care for Women Unit, were necessary to request the information. The Ministry staff explained that they did not manage or produce consolidated budgetary information on maternal health. After several attempts, the CSOs were able to obtain detailed information on contraceptive method expenditures and some expenditure information on instruments and equipment (such as forceps and speculums) distributed to hospitals for maternity care. No information on essential medicines for obstetric care was provided, however (Table 2). The research showed that existing budgetary information for the country's Plan to Reduce Maternal Mortality was insufficient even for those responsible for the Plan's implementation.

In Guatemala, the CSO was able to start the search on the internet utilizing the General Planning Secretariat's restricted access webpage, as they were given the password. The webpage had sufficient information to identify the budget line for contraceptives funded by international donors, but the information was not disaggregated by method. Other budget lines were grouped by general pools of resources, such as the medicines and supplies budget, that included not only those for obstetric care, such as oxytocin and misoprostol, but also other non-maternal health-related medicines. As a result, further information was requested under Freedom of Information. The Access to Information Unit of the Ministry of Health referred the requests to each of the National Hospitals and Regional Health Departments, which in turn, sent detailed information on the funds they had spent the previous year on medicines for emergency obstetric care and training of midwives and nurses (Table 3). As there was no one at the Ministry of Health responsible for gathering and systematizing this information, the various health entities sent the information requested to the Access to Information Unit, which was in multiple files in a variety of formats, which were then forwarded on to the CSOs. This large volume of information was very difficult to manage and analyze.

In Panama, the search process was particularly difficult, both because the budget and policy information was not available on the internet and because formal requests submitted under Freedom of Information went unanswered. Initial interviews with Ministry of Health staff resulted in referrals to 14 local health units across Panama that produced their own information, which it was neither feasible nor reasonable for the CSOs to try to gather and analyze. Upon a subsequent request, the Ministry of Health provided aggregated information that was difficult to interpret (Table 4). For instance, information on medicines and supplies for obstetric care fell under “medical and dental equipment”, and the Reproductive Health Programme budget came under the Population Department, with no information on specific reproductive health budget allocations. The Head of the Reproductive Health Programme explained that there was no budget, and that instead, they managed a general pool of resources that were transferred to local health units as needed. However, there were no mechanisms for local health units to report back to the Department on how they had spent those funds. In this case, the lack of available budgetary information and planning at the Ministry level, as well as the absence of expenditure reports by local health units, made budget tracking nearly impossible for the CSO concerned.

In Peru, most of the maternal health budgetary information was available online under the Maternal Mortality Strategic Plan budget line (Table 5). The “Economic Transparency” website provided information on budget and expenditures for each category of the Plan, such as usage of antenatal care and number of skilled personnel who attended normal and complicated deliveries. However, the information was aggregated, with no specific budgetary data on, for example, staff training or funds allocated to purchase uterotonics or folic acid. After accessing this basic information on the website, the CSO submitted a request under Freedom of Information and met with staff from the Ministries of Health and Finance. The Ministry of Finance claimed they did not have more detailed information and referred them to the Ministry of Health, who in turn did not provide any information.

As the tables show it was only in Peru that most of the information was available publicly, that is, from a government website. In the other four countries, none of the information was available publicly, and although it was possible to obtain at least some data on maternal health budgets from government and health system sources, the search process took a complex course in most cases. The data collected in each country were very different, depending not only on the level of budget transparency, but also on the existence and form of the data collection systems that the governments themselves utilized. For instance, when a budget item was under the scrutiny of international donor organizations, as was the case with contraceptives in Guatemala and El Salvador, specific budgets were often earmarked for this purpose which made it easier to find the budget information requested. But this was often not the case otherwise.

In many cases, governments did not produce the requested information to the level of detail requested, and therefore, their responses were often indirect or only aggregated information was provided. Only some information on emergency obstetric care and antenatal care was provided with the detail specified in the request for information, and very little data on skilled attendance at delivery were provided. Overall, considering all the categories and types of information requested, we can say that on average, only about half the information requested was provided.

This study showed that it was necessary for the CSOs to utilize not only national laws on freedom of access to information but personal contacts within government – particularly within health ministries – to gather budgetary information on maternal health services. There is still a long way to go before governments themselves – let alone civil society – are able to gather and put together all the information necessary to analyze and assess their investments in maternal health. The resulting lack of information available meant, for civil society, that their ability to monitor public budgets and programme implementation was greatly hindered as well.

Discussion

The ultimate goal of maternity services is to prevent and reduce to a minimum maternal deaths related to pregnancy and childbirth. To support and work with governments to achieve this goal, CSOs need access to government policies, plans and budgets on maternal health, not only to influence them, but also to hold governments accountable. Indeed, this holds true also for reducing abortion deaths, which constitute 15% of maternal deaths in the Latin American region,Citation1 and for improving access to family planning and to all reproductive and sexual health care, of which maternal health care is an important part.

This case study has shown that there is a clear need for governments to improve information systems and transparency on maternal health spending and to further examine and improve their information systems on all reproductive and sexual health care. Furthermore, governments should ensure that information is made public in a timely way, and is accessible and comprehensive. Only then will CSOs be able to monitor spending on implementation of services and hold governments accountable.

Since the information the CSOs were looking for in this case was often spread out among different ministries or among different sections within the same ministry, or was available only from district or local departments and hospitals, CSOs had to make multiple requests for information, in some cases from all of these sources and in some cases, were still not able to obtain comprehensive information.

Since maternal health care funds are often disseminated in a decentralized way, it is critical to have a system for local governments and local health units to report to central government so that central government can effectively assess local and overall implementation of maternal health policies, accurately account for spending on these programmes, and plan ahead accordingly.

Focusing on specific aspects of maternal health – from contraceptive supplies to skilled personnel, to essential medicines for antenatal and emergency obstetric care – captured a significant amount of useful data, but there are other factors that also greatly affect maternal health. For instance, government policies and investments to address gender inequality and improve public transport should be considered when designing accountability and monitoring systems and the bodies responsible for them.

Despite the difficulties that arose during this case study, there are reasons to be optimistic. The Global Strategy, and the establishment of the related Commission on Information and Accountability for Women's and Children's Health, represents a clear opportunity for scaling up analysis of maternal health investments. Following a recommendation of the Commission, the UN Secretary General recently appointed an independent Expert Review Group, which will issue reports on information and accountability to the General Assembly over the next three years. It is crucial that this group addresses the obstacles to CSO monitoring of the Global Strategy at the national and sub-national level, and maximizes the opportunity for CSOs to inform the Expert Group's reports.Citation16

An active civil society voice is a key element in ensuring government spending is transparent and is being used effectively to implement – and improve – existing policies and programmes. Civil society, in particular sexual and reproductive health and rights organizations, that have real-life knowledge and programmatic experience in addressing the barriers to achieving maternal health need to be able to play an essential role in tracking their governments' progress in preventing maternal deaths.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the following for their critical eye, insightful comments, excellent edits and their support and time: Giselle Carino and Flor Hunt, International Planned Parenthood Federation/Western Hemisphere Region; Manuela Garza, International Budget Partnership; and Ukaid, Department for International Development, and the Hewlett Foundation for their support.

Notes

* It is not the purpose of this paper to present a methodology on how to track maternal health expenditures, but rather a methodology to assess how much budget information is available, from which civil society can learn how much governments are spending. A next step might be to use this information to track whether or not programmes are being implemented effectively, but the first step was to consider whether or not it was possible to obtain the information in the first place.

References

- A Acosta, E Cabezas, J Chaparro. Present and future of maternal mortality in Latin America. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 70: 2000; 125–131.

- UN Department of Public Information. We can end poverty: 2015 Millennium Development Goal. September 2010. At: http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/MDG_FS_5_EN_new.pdf

- World Health Organization. Women and Health, today's evidence tomorrow's agenda. 2009. At: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241563857_eng.pdf

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy for Women's and Children's health. 2010. At: http://www.who.int/pmnch/topics/maternal/201009_globalstrategy_wch/en/

- A Germain. Ensuring the complementarity of country ownership and accountability for results in relation to donor aid: a response. Reproductive Health Matters. 19(38): 2011; 141–145.

- World Health Organization. Framework and standards for country health information systems. Health MetricsNetwork, 2008. At: http://www.who.int/healthmetrics/documents/hmn_framework200803.pdf

- World Health Organization. Country health information systems: a review of the current situation and trends. Health Metrics Network, 2011. At: www.who.int/entity/healthmetrics/news/chis_report.pdf

- M Garza, B Alemu, J Lakin. Toward Accountability for Resources: Independent Budget Monitoring of the Global Strategy for Women's and Children's Commitments. 2010; IBP: Washington, DC.

- United Nations Population Fund. State of the World Population 2008, UNFPA, 2008. At: http://www.unfpa.org/webdav/site/global/shared/documents/publications/2008/swp08_eng.pdf

- International Budget Partnership. Open Budget Survey, 2010. At: internationalbudget.org/what-we-do/open-budget-survey/rankings-key-findings/rankings

- World Health Organization UNICEF UNFPA World Bank. Packages of interventions. Family planning, safe abortion care, maternal, newborn and child health. WHO/FCH/10.06. 2010; WHO: Geneva.

- World Health Organization. WHO recommended interventions for improving maternal and newborn health. 2007; WHO: Geneva. At: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2007/who_mps_07.05_eng.pdf

- Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health. Consensus for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health. 2009; WHO: Geneva.

- K Keith-Brown. Investing for life: making the link between public spending and the reduction of maternal mortality. 2005; Fundar, Centro de Análisis e Investigación: Mexico DF.

- S Cohen. Promoting sexual and reproductive health advances maternal health. Guttmacher Policy Review. 3(2): 2009. At: www.guttmacher.org/pubs/gpr/12/2/gpr120208.html

- Commission on Information and Accountability for Women's and Children's Health WHO. Keeping promises, measuring results. 2011. At: www.everywomaneverychild.org/images/content/files/accountability_commission/final_report/Final_EN_Web.pdf