Abstract

In Nepal, India, Bangladesh and Pakistan, policy focused on improving access to maternity services has led to measures to reduce cost barriers impeding women's access to care. Specifically, these include cash transfer or voucher schemes designed to stimulate demand for services, including antenatal, delivery and post-partum care. In spite of their popularity, however, little is known about the impact or effectiveness of these schemes. This paper provides an overview of five major interventions: the Aama (Mothers') Programme (cash transfer element) in Nepal; the Janani Suraksha Yojana (Safe Motherhood Scheme) in India; the Chiranjeevi Yojana (Scheme for Long Life) in India; the Maternal Health Voucher Scheme in Bangladesh and the Sehat (Health) Voucher Scheme in Pakistan. It reviews the aims, rationale, implementation challenges, known outcomes, potential and limitations of each scheme based on current available data. Increased use of maternal health services has been reported since the schemes began, though evidence of improvements in maternal health outcomes has not been established due to a lack of controlled studies. Areas for improvement in these schemes, identified in this review, include the need for more efficient operational management, clear guidelines, financial transparency, plans for sustainability, evidence of equity and, above all, proven impact on quality of care and maternal mortality and morbidity.

Résumé

Au Népal, en Inde, au Bangladesh et au Pakistan, la politique centrée sur l'élargissement de l'accès aux services de maternité a débouché sur des mesures de réduction des obstacles financiers qui empêchent les femmes d'avoir accès aux soins, plus précisément des transferts de fonds ou des chèques conçus pour stimuler la demande, notamment de soins prénatals, obstétricaux et du post-partum. Pourtant, en dépit de leur popularité, on sait peu de choses de l'impact de ces programmes. L'article décrit cinq interventions majeures : le programme Aama (des mères) (élément de transfert de fonds) au Népal, le Janani Suraksha Yojana (plan de maternité sans risque) en Inde, le Chiranjeevi Yojana (plan pour une longue vie) en Inde, le projet de chèques de santé maternelle au Bangladesh et le système de chèques Sehat (santé) au Pakistan. Il examine les objectifs, les justificatifs, les obstacles à l'application, les résultats connus, le potentiel et les limites de chaque projet, avec les données disponibles. Un recours accru aux services de santé maternelle a été enregistré depuis le début des projets, mais sans qu'il soit possible de déterminer les améliorations de la santé maternelle, faute d'études contrôlées. L'étude recense les domaines d'amélioration des projets qui ont besoin d'une gestion opérationnelle plus efficace, de directives claires, de transparence financière, de plans de viabilité, de preuves d'équité et, surtout, de confirmer leur impact sur la qualité des soins, et la mortalité et morbidité maternelles.

Resumen

En Nepal, India, Bangladesh y Pakistán, debido a políticas centradas en mejorar el acceso a los servicios de maternidad, se ha intentado reducir las barreras de costo que impiden el acceso de las mujeres a los servicios: específicamente, transferencias de dinero o programas de cupones diseñados para estimular la demanda de los servicios, incluida la atención antes, durante y después del parto. Pese a su popularidad, no se sabe mucho acerca de su impacto o eficacia. En este artículo se resumen cinco intervenciones importantes: el Programa de Madres (transferencias de dinero) en Nepal; el Plan por una Maternidad sin Riesgos y el Plan por una Vida Larga, ambos en India; el Programa de Cupones para Servicios de Salud Materna en Bangladesh; y el Programa de Cupones para servicios de salud, en Pakistán. Se analizan los objetivos, la justificación y los retos de la implementación, los resultados, el potencial y las limitaciones de cada plan según los datos. Desde el inicio de estos planes, ha aumentado el uso de los servicios de salud materna, aunque por falta de estudios controlados no hay evidencia de mejoras en los resultados. Entre las áreas a mejorar figuran: la eficiencia de la administración operativa, directrices claras, transparencia financiera, planes de sostenibilidad, evidencia de equidad y, sobre todo, un impacto comprobado en la calidad de la atención y en las tasas de mortalidad y morbilidad maternas.

Maternal mortality and morbidity remain high in Nepal, India, Bangladesh and Pakistan, and policy in the region has focused increasingly on skilled attendance at birth to reach Millennium Development Goal 5.Citation1–3 In these countries, however, women's uptake of maternal health care services remains strongly associated with wealth, and high financial costs are considered a major barrier in maternal health care utilisation.Citation1,3–6 Against this background, governments and donors are exploring ways to reduce cost barriers for pregnant women.Citation5 Several demand-side financing schemes, designed to stimulate demand for maternal health care, have been implemented in South Asia. These include voucher schemes, where all or part of the cost of services are paid for specific groups, and cash transfer schemes, where women are reimbursed for the costs of maternity services.Citation2,7 In spite of the popularity of these schemes with policymakers, there is as yet insufficient evidence of their impact.Citation8 Rigorous evaluations are lacking, particularly evidence of effects of the schemes on utilisation, targeting, quality of care and maternal mortality and morbidity. In most cases, data on outcomes (maternal, perinatal and neonatal mortality) are limited or not yet available, though some evidence is beginning to emerge.

This paper provides an overview of five major financing schemes designed to stimulate demand for maternal health care in South Asia: the cash transfer element of Nepal's Aama Programme (formerly Safe Delivery Incentive Programme); India's Janani Suraksha Yojana (Safe Motherhood Scheme) and Chiranjeevi Yojana (Long Life Scheme); Bangladesh's Maternal Health Voucher Scheme and Pakistan's Sehat (Health) Voucher Scheme. It reviews the aims, rationale, implementation challenges, known outcomes, potential and limitations of each scheme based on currently available data, lessons learned to date and implications for health care practitioners, policymakers, researchers and those with an interest in widening access to maternal health care in low- and middle-income settings.

Methodology

We reviewed the literature on demand-side financing schemes for maternal health in South Asia, and specifically, the characteristics of the different schemes, how they are implemented and any known impact on maternal mortality and other outcomes. We included published journal articles including systematic reviews of demand-side financing mechanisms more widely, primary research evaluating demand-side financing schemes in South Asia as well as reports from key international agencies and governments, policy documents, and other grey literature.

To identify published literature we performed electronic searches of the following databases: Scopus, Medline, Web of Science, Global Health, CINHAL Plus and Applied Social Science Index. We developed a comprehensive search strategy using the following search terms, independently or in combination, with no date restriction: wom*, girl*, mother*, adolescent*, female*, demand-side finance*, public-private partnership, PPP, cash transfer*, money transfer*, CCT*, voucher*, maternal health, reproductive health, pregnanc*, birth*, maternal death*, maternal mortalit*, maternal morbidit*, institutional deliver*, facility deliver*, hospital deliver*, South Asia*, India*, Bangladesh*, Pakistan*, Nepal*, Sri Lanka*, Bhutan*, Maldives*.

We screened titles and abstracts of all retrieved articles (n=502) to identify those meeting our inclusion criteria. We then scrutinised the full text of these articles to identify relevant information. Overall, we included 38 published journal articles in the review. We also searched Google for related reports and grey literature, retrieving 14 reports, bulletins and policy documents relevant to the review.

Maternal health context and health care utilisation trends

Across all four countries over two-thirds of health expenditure occurs in the private sector at present and out-of-pocket costs to patients are some of the highest in the world.Citation2,9,10 Consequently the maternal health care needs of women are frequently unmet, and maternal mortality rates are amongst the highest globally.Citation9 In the following sections we provide a broad overview of each country's maternal health outlook and health care utilisation trends over the past decade.

Nepal

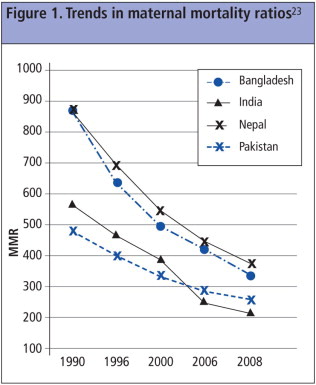

Maternal health has been a key policy focus in Nepal and the country has made some progress in improving maternal health over the past decade.Citation3 Recent figures suggest maternal mortality has decreased from 550 per 100,000 live births in 2000 to 380 in 2008 (). Though it has not been possible to isolate the drivers of the recent maternal mortality decline, it is likely to be partially due to the legalisation of abortion in 2002.Footnote* Societal changes in education and wealth also seem to have contributed.Citation11 In spite of this improvement, however, utilisation of maternal health services remains low, with estimates of 19% of women delivering in a facility.Citation12 In mountainous areas, skilled birth attendance is estimated at just 7%.Citation3 A national free delivery policy was launched in Nepal in January 2009, though reports of user charges persist and outcomes of this policy are still being monitored.Citation13

India

India's major problems affecting health care utilisation include a wide socioeconomic gap between rich and poor and marked inequities in access to health care. India as a whole has high numbers of maternal and neonatal deaths.Citation14–16 Between 1992 and 2006, two national surveys showed that the proportion of institutional deliveries overall showed little increase, from 26% to 41%.Citation17,18 Nevertheless, more recently India has driven the decline in the maternal mortality ratio for South Asia (), as skilled birth attendance has increased in recent years.Citation19

Pakistan

In Pakistan maternal health indicators have stagnated, and reduction in the maternal mortality ratio has been slow ().Citation2 Critical problems in the health sector include poor governance, insufficient per capita health expenditure, and low capacity and low coverage of skilled birth attendance.Citation2 The 2007 Pakistan Demographic & Health Survey (DHS) reported that 39% of women in small urban areas had skilled attendance at birth, only a small increase from the 35% reported in the 1990 survey.Citation20,21 The same surveys reported institutional delivery had risen to 37% in 2007 from 13% in 1990.Citation20,21

Bangladesh

Perhaps due to its rising income and education levels, Bangladesh has seen a greater reduction in its MMR than Pakistan.Citation1 Despite this, most births (79%) take place without skilled attendance and the public sector is characterised by inadequate supplies and equipment, high absenteeism and vacant posts.Citation1 In Bangladesh, every year about three million deliveries take place and around 12,000 women die due to pregnancy-related causes.Citation22 While only 12% of deliveries had skilled birth attendance in 2000, this proportion had increased to 20% in 2006.Citation22

Difficulties in access to maternal health care

In all four countries, use of maternal health care services is limited despite increased inputs from governments and international donors.Citation24 Though use of antenatal care, skilled birth attendance and emergency obstetric care are mediated by a range of factors, there is increasing evidence that financial and other barriers are important in determining service uptake.Citation1,25 Government and donor investment in improvements in service availability, training, drugs and equipment are offset by persisting difficulties with access to care experienced by poor women and their families.Citation8 The barriers women face are usually multiple and overlappingCitation24 and include: a lack of information about where and when to seek care; distance to a facility; substantial direct and indirect costs; age and gender-based norms concerning decision-making; the impact of status and caste; the allocation of family resources for women's health, and socio-cultural norms favouring home births over institutional deliveries.Citation1,24,26 Of these obstacles, the cost of services and other financial barriers are perceived by poor women as one of the major reasons against delivering in a health facility.Citation2,3,27 Health policy and decision-makers have therefore focused attention on mechanisms to address the cost barriers that women face.Citation1,8

Aims of demand-side financing for maternal health care in South Asia

Demand-side financing interventions aim to channel funds and/or services to individuals who may otherwise struggle to access them.Citation1,2 In South Asia, five major demand-side finance schemes piloted or implemented to date are variants of cash transfer schemes (Nepal, India) and voucher or voucher-like schemes (India, Bangladesh, Pakistan). Cash transfers reimburse users for monies spent on maternal health care services. It is hypothesised that cash incentives will engender behaviour change and encourage health-seeking behaviour.Citation12 At the same time, they are considered more relevant than simply free service provision, as they often cover extra costs, such as transport.Citation3 If designed and implemented well, it is argued that cash transfers are affordable and cost-effective for funders and can be scaled up easily.Citation9 Both the major cash transfer schemes in Nepal and India are deployed nationwide.

Rather than channelling funds direct to the user, voucher schemes partially or wholly subsidise users to purchase services from accredited providers.Citation28 In some schemes, physical vouchers are dispensed with, but funders incentivise selected providers to deliver their services at an affordable cost to women.Citation2 Voucher schemes are usually targeted, and it is anticipated that this will improve access to care amongst poor women.Citation2 Voucher schemes allow women to choose providers, and revenue earned by participating clinics is directly proportional to the number of scheme users attending their facilities.Citation29 It is hoped that this will increase competition and, subsequently, improve quality as providers compete to attract a higher number of women participating in the schemes.Citation29 It is also argued that the accreditation required for providers to join the scheme (the process of which varies) can ensure minimum quality standards.Citation28 Voucher schemes are theoretically viable in South Asia given its substantial private sector, though as with cash transfer schemes, they are not always implemented as planned.

At the same time, while the promotion of antenatal care, institutional delivery and post-partum care should, in principle, realise the goal of reducing maternal mortality,Citation6,30,31 countervailing evidence suggests that poor standards of care in India (for example) continue to result in deficient services or deaths among women who seek institutional deliveries.Citation16,32 These failures in both public and private facilities include a lack of staff training, poor referral systems, weak accountability mechanisms and inadequate information systems.Citation16,32 The question remains whether demand-side financing mechanisms alone can improve quality of care sufficiently to reduce maternal deaths.

Characteristics, implementation and impact of the schemes

Nepal

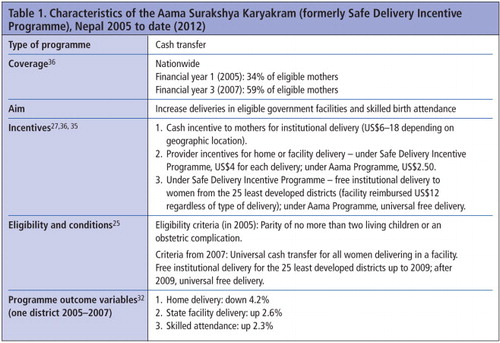

The Nepal Safer Motherhood Project 1997–2004 prompted significant policy interest in maternal health.Citation3,33,34 Research into costs consolidated support for demand-side financing, and the Safe Delivery Incentive Programme was launched in 2005. Since 2009, it has continued within Nepal's wider Aama Programme and was recently rebranded as Aama Surakshya Karyakram.Citation13,35 At the time of the scheme's inception, the wife of the then Prime Minister was a women's activist and her strong support of the Safe Delivery Incentive Programme was considered key in its introduction.Citation3

The scheme, funded by the Government of Nepal and UK Department for International Development, combines a cash incentive for women with an incentive to public providers, with plans ahead to roll it out to private providers.Citation13 Women are paid for delivery in a facility and some transport costs, and women from the least developed districts under the Safe Delivery Incentive Programme could access health care for free (since the introduction of Aama, free delivery is now universal).Citation3,12 Skilled providers are also incentivised for facility deliveries and for home deliveries, given that difficult terrain in Nepal renders many facilities inaccessible.Citation27,36 Health providers pay women in cash directly upon discharge. Rather than target the scheme towards the poorest, the government chose universal targeting, ostensibly for equity though it is also easier to manage and popular politically.Citation12

Initially, the Safe Delivery Incentive Programme was limited to women with two or fewer children, with the aim of reducing the fertility rate. This condition was later rescinded because it penalised the poorest women.Citation3 Uptake was slow initially, due mainly to lengthy delays in the release of funds to both providers and beneficiaries, confusion caused by promoting both institutional and home delivery, and a lack of transparency concerning which health workers should receive what incentive, which led to some resentment.Citation12,37 The Aama Programme reports that learning from the Safe Delivery Incentive Programme is now reflected in better management procedures,Citation38 but while impact of the universal free delivery service is emerging,Citation13 a robust impact assessment of the cash transfer part under the guise of Aama Surakshya Karyakram is yet to emerge. As the Safe Delivery Incentive Programme, estimates of coverage varied, but reports suggested the scheme covered between 29%Citation12 to 59%Citation36 of eligible mothers in 2008–09. Reports suggest home deliveries declined under the scheme while facility deliveries and deliveries with skilled attendance increased (Table 1).Citation37 A small, exploratory and cross sectional descriptive study of the Aama Surakshya Karyakram found that all the mothers in their study (n=47) had received free delivery services, but knowledge of the transport incentive was limited, and the scheme is still struggling to reach women in remote areas.Citation35 At the same time, confusion persists over the purpose of the scheme. Women in the study knew there were cash payments available, but were unsure exactly what purpose they were for.Citation35

India

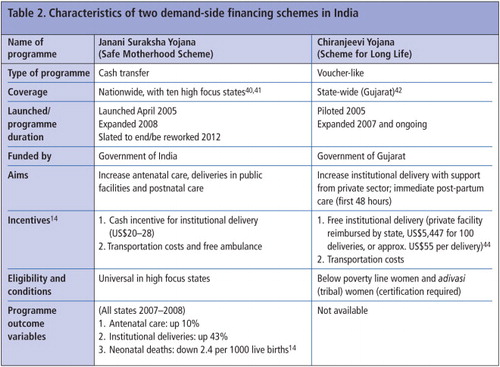

The Janani Suraksha Yojana (Safe Motherhood Scheme) was launched in 2005 and is the largest cash transfer scheme for maternal health care in the world.Citation14 Funded by central government, it is administered through the National Rural Health Mission, a temporary adjunct structure to the regular health directorate. Piloted in a small number of states originally, the scheme expanded nationally in 2008, but retains a focus on low-income states. In the latter, targeting is universal and the cash incentive higher.Citation14 The scheme aims to normalise facility deliveries amongst women, paying US$ 20–28 per delivery (see Table 2).Citation14 A small amount of cash is also available for home births. Originally, the scheme was open to both public and private providers, but at this writing largely excludes the private sector, though there is some state variation. The scheme has introduced a new type of health worker – Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) – who are paid to accompany women to antenatal check-ups, delivery and post-partum visits. The scheme has seen rapid scale-up, with US$275 million allocated to its budget in 2008–2009, exceeding US$340 million in 2009–2010. Coverage for 2010 was expected to be nearly a third of all women giving birth in India that year. In practice, however, coverage is highly variable, from less than 5% to 44% in different states, while women of middle income were found most likely to benefit from the scheme.Citation14 Nevertheless, available data suggest institutional deliveries increased by 8% in rural areas between 2002–2008.Citation14 Reports concerning poor quality of care are beginning to emerge,Citation16,39 placing question marks over the ability of institutions to cope with the increased demand. Anecdotal evidence suggests that some states were unprepared for such rapid increases in institutional deliveries.Citation40

The other major demand-side financing scheme implemented in India is the Chiranjeevi Yojana (Scheme for Long Life), a public-private partnership operating in Gujarat state (Table 2). The scheme (best described as “voucher-like”) provides free institutional delivery to poor women by contracting out delivery services to private obstetricians. The rationale for this scheme is that emergency obstetric care is more widely available in Gujarat in private services than in public services.Citation43 Piloted initially in a few districts, the scheme was rolled out state-wide in 2007 under the supervision of a committed Health Commissioner.Citation43 The Government of Gujarat pays a fixed pre-determined amount (US$ 5,447 for 100 deliveries) to each private obstetrician.Citation44 This is paid part in advance, part retrospectively. The flat rate payment includes both normal and complicated deliveries, to remove any incentive to carry out surgical interventions.Citation42,43 As well as free delivery, the scheme provides free food and medicines after delivery and reimbursement of transport costs for accompanying family members.Citation42,43 The scheme is targeted at poor women and beneficiaries must present either a below poverty line (BPL) card or pre-specified certificate of poverty to access the services free of charge. One study reports 865 of around 2,000 private practising obstetricians have joined the scheme and coverage of deliveries among the poor in the state averaged 53%.Citation45 Another study reports that 66% of Chiranjeevi Yojana beneficiaries were satisfied with the services.Citation43 So far, the scheme attributes its successes to the widespread availability of private obstetrician–gynaecologists in rural areas willing to collaborate with the government scheme,Citation46 though other reports question the popularity of the scheme among rural providers.Citation47 Such claims, the efficacy of the scheme's incentives and declarations of transparency in its financial arrangements, all need to be evaluated. We could not find any data on the impact of the scheme on utilisation of antenatal care, institutional delivery or post-partum care.

Bangladesh

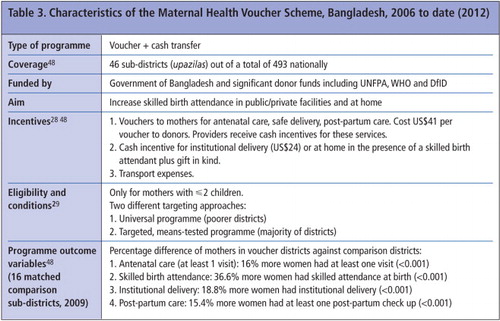

In Bangladesh, the Maternal Health Voucher Scheme was launched in 2006 with external support from a combination of donors including UNFPA, WHO and DFID. As with India's Janani Suraksha Yojana, the scheme is administered and delivered via a parallel structure to the regular health directorate. The scheme covers 46 of 493 upazilas (sub-districts) nationally, providing vouchers to mainly poor women with fewer than two children.Citation29 The scheme costs the funders US $41 per voucher distributed.Citation48 The vouchers entitle the bearer to free antenatal care, post-partum care and skilled birth attendance (at home or in a facility) (Table 3).Citation1 In addition to the voucher, the scheme includes a cash incentive for skilled birth attendance, transport costs, a gift package including food, and a cash incentive to providers to offer free services.Citation28 Health workers distribute the vouchers to women, which are redeemable – in theory – at both public and private facilities.

Since its inception, the scheme has reported a rapid increase in the use of antenatal care, institutional delivery and post-partum care, which corresponds closely to an increase in voucher uptake.Citation1,8 In a recent matched comparison study (the strongest study design of any evaluation in the region so far), the likelihood of women having an institutional delivery had increased by almost twofold.Citation48 At the same time, studies report women beneficiaries' satisfaction with the schemeCitation29 and increased equity in access for poor women.Citation8

Despite these considerable successes, the scheme has encountered a number of difficulties, including delays in the release of voucher funds, and confusion over beneficiary selection criteria, both of which are likely to impact on uptake of the scheme. Reports suggest that the low level of funds available and poor financial management have failed to attract private providers. Competition among providers has therefore not increased, quality of care has not improved and participation is limited to the public sector.Citation29 In Bangladesh, the scheme remunerates providers for caesarean sections, and reports suggest an increase in surgical deliveries, but it is unclear if this is due to the scheme and/or other factors.Citation1,48 Recent data reveal that out-of-pocket expenditure persists for women beneficiaries of the scheme, indicating that the scheme has not eliminated financial barriers to maternal health care.Citation48 Finally, questions remain over the capacity of government facilities to cope with the scheme in view of rapid increases in utilisation. As in the other countries, there has been little investigation into the impact on quality of care of this surge in demand.

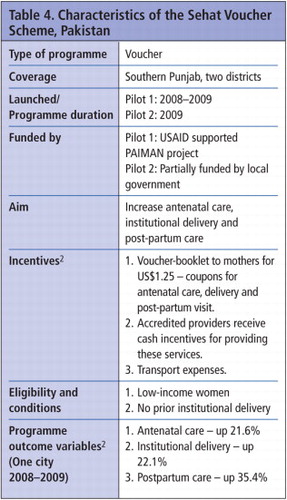

Pakistan

The USAID supported Sehat (Health) Voucher Scheme was piloted in two districts in Southern Punjab between 2008–2009. The services available to women included three antenatal care visits, normal delivery (referral in the case of caesarean section) and one post-partum care visit (Table 4).Citation50 The first pilot targeted 2,000 pregnant women in one of the poorest districts in Pakistan (Dera Ghazi Khan City), identified according to amenities in the recipients' neighbourhoods, income level and no prior experience of delivery in a facility.Citation2 The scheme had no parity criteria; indeed, the women who were sold the booklets had more children than those who were not (38% had five or more children).Citation2,50 Women receiving vouchers could use services provided by a network of pre-approved private providers (part of the non-governmental organisation Greenstar Social Marketing).Citation2,50

Scheme beneficiaries made a one-off payment of US$ 1.25 to Greenstar outreach workers for the voucher booklet. The outreach workers worked extensively in communities promoting the schemes. After providing the services, providers were reimbursed by Greenstar on submission of the vouchers.Citation2 Reports suggest the scheme was successful in selling almost 100% of its target of 2,000 booklets.Citation50 One study indicates an increase in institutional delivery associated with participation in the voucher scheme, with no secular trend showing an increase in facility delivery during the same study period.Citation2 The second pilot, implemented in Jhang District was part-government funded. Support for the scheme has grown within the public sector (in particular, the Punjab Director General-Health has been supportive of the scheme). Reports in 2009 recommended its continuation and scale-up, though this has not yet happened.Citation2,50

Overall findings

In this review we have outlined the available information to date on the key characteristics, implementation and to a limited extent the impact of demand-side financing schemes to improve access to maternal health care in four countries in South Asia. While each scheme differs in its finance mechanism, incentives offered and target population, the common aim has been to reduce financial barriers to accessing maternity care. The intended impact of these schemes is to encourage utilisation of services in order to improve pregnancy outcomes, particularly amongst the poor. Here we reflect on the extent to which these types of schemes have been shown to meet their intended impact on utilisation, equity, quality of care, sustainability, and maternal mortality and morbidity.

Utilisation

All schemes except India's Chiranjeevi Yojana (for which there are not yet reported data) report increased utilisation of maternity services in areas where they are operational.Citation2,14,29,37 However, confounding factors need to be controlled for, to be confident about causality.Citation1 A number of factors are likely to have an impact on uptake of services, particularly inefficient disbursement of funds. Slow payment of incentives can arise from bureaucratic mismanagement, or from rolling out a scheme before it is ready because it is politically expedient to do so. The delayed release of funds will result in continued out-of-pocket payments by women, or the need for providers to reimburse eligible women from their own non-scheme funds. As a result, service users' trust may be eroded, not just for maternity care, but for all health services, and providers may avoid the schemes or perceive them to be a financial liability.

Lack of clarity, systemisation and difficulties in communicating policies to both implementers and the public are also likely to diminish support. For example, in Nepal, providers were confused about the purpose of the scheme – ostensibly it was to encourage facility delivery, yet incentives were available for home delivery too. Lack of clarity can de-motivate providers and administrators, which will impact on users' perceptions. In all cases, success will depend on workable incentives and the willingness of providers to participate. At the same time, lack of transparency about health workers' roles and responsibilities can erode support for the schemes, as seen among some workers in Nepal.Citation12 Similarly, the role of the new Accredited Social Health Activists deployed by India's Janani Suraksha Yojana will need to be carefully examined. There are a number of existing community health workers in rural India and possible duplication of roles has the potential for dissatisfaction and conflict between them.

Alongside provider incentivisation, the schemes depend for their successful promotion on mass media campaigns and committed workers in the community. Pakistan's Sehat Voucher Scheme was highly dependent on its outreach workers to raise awareness of the scheme.Citation2 What has emerged from the literature is the importance of piloting the schemes, clear direction from funders (whether government or donors), training, close supervision, regulation and monitoring.

Corruption

Where schemes involve financial incentives, policymakers, funders and administrators must be alert to the possibility of misuse of funds, and some misuse has been reported.Citation12,29 Cash transfer schemes in particular involve the handling of large sums of money which are disbursed directly to service users and to some health workers by health centres. In the Nepal scheme, it was noted that the use of cash rather than a voucher system meant that money was transported from the district health office to the health facility.Citation12 Where bank accounts and accountants do not exist, health workers handle substantial funds and this carries some risk. Where vouchers are used, there is potential for facilities to claim reimbursements for services not rendered. Pakistan's Sehat Voucher Scheme implemented spot checks in an attempt to deter this.Citation2

At the same time, extra funding provided for surgical intervention can create perverse incentives for unnecessary care. While there is a guard against this in India's Chiranjeevi Yojana (providers are paid a flat rate per 100 deliveries, with an estimated proportion of complicated deliveries factored in), in Bangladesh practitioners are remunerated personally for conducting caesarean sections. As noted, an increase in surgical intervention has been observed in Bangladesh, though it is not possible to pinpoint causation.Citation1 By contrast, the risk in India's Chiranjeevi Yojana appears to be problems with referral of women with complications, since there is no incentive for private providers to accept them as patients. As the majority of maternal deaths arise from complications, the frequent referral of complex cases by private providers back to the public sector makes us doubt the ability of such schemes to have an impact on maternal mortality.

In all schemes, there must also be vigilance about the possibility of persisting demands for payment of unofficial user fees, of which we have heard anecdotal (but undocumented) evidence, when women are supposed to be receiving free care.

Funding and sustainability

India's two schemes are state funded, and this suggests sustainability. Nevertheless, the parallel structure used to deliver India's Janani Suraksha Yojana must be closely examined, particularly with respect to the dangers of duplication and the impact on sustainability where funding for the structure is due to expire. Bangladesh's Maternal Health Voucher Scheme also operates via a parallel platform; at the same time, the scheme entails considerable financial commitment yet a clear strategy on the part of the government to independently support the scheme has not yet been established.Citation48 Nepal's Aama Programme is also part donor funded and this has raised concerns about the lack of ownership at the district level.Citation12 The first pilot of Pakistan's Sehat Voucher Scheme was entirely donor-funded, though it has received some public support for the second pilot.

A strong political champion has been a significant boost to India's Chiranjeevi Yojana and Nepal's and latterly to Pakistan's schemes as well.Citation2,3,45 Short-term or insecure funding sources inevitably prompt urgent questions about scale-up and longevity. A major concern is the outcome when a scheme comes to an end, and what happens when both providers and women have come to expect the financial incentives.Citation48 The hope is that the schemes will prompt so-called behaviour change, but if the main aim of the schemes is to remove financial barriers, the point is not behaviour. In any case, it is not yet possible to evaluate the long-term impact of any of the schemes described here.

Equity

Demand-side financing aims to redress inequitable access to health care, but targeting is often difficult.Citation51 In some areas, the majority of households are likely to be poor, and schemes in Nepal, Bangladesh and India's Janani Suraksha Yojana are universal due to the impracticality of socio-economic targeting.Citation1,14 Criteria based on number of children are often considered discriminatory, since the poorest women are likely to have more children. Nepal has subsequently removed this condition, but it remains in Bangladesh for fear of encouraging higher fertility.Citation1 India's Chiranjeevi Yojana and Pakistan's Sehat Voucher Scheme seem to be confident in their reports that the majority of their beneficiaries are poor,Citation2,42,43 though if schemes are not adequately reaching rural areas this raises question marks about capacity to reach the poor. Among all schemes, more effort is needed to ensure that the poorest and most marginalised have equitable access to the benefits, especially those schemes that are now universal.Citation30 It is also possible that adoption of universal targeting may derive from political motivation to gain popularity with voters.Citation12,28 Above all, when designing schemes intended to benefit specific groups, the opinions and needs of those groups should be sought, but they rarely are.

Quality of care

Few studies or reports focus on the quality of care provided in facilities that participate in these schemes. In both public and private sectors, it is anticipated that competition between providers for incentives will act as a catalyst for improvements to quality of maternity care. While there is evidence that utilisation of services has gone up, there is less evidence that the schemes have led to improvements in services. For example, Bangladesh's scheme has not increased competitiveness or attracted private providers,Citation29 and India's Janani Suraksha Yojana scheme has largely excluded private providers. The rationale for this needs to be explored. Preliminary assessments across schemes have found that service quality, in general, remains poor.Citation8,37,49 Intuitively, a rapid increase in utilisation is likely to place a considerable burden on facilities and compromise quality in the short term, and there is no evidence to suggest that this has stimulated expansion of or improvements in services. Given the limited extra capacity in public and private sector facilities in South Asia, scheme funds need to focus not just on widening access, but on ensuring that facilities can cope with the increased demand they tend to generate. Quality is both a supply and demand issue.

Maternal, perinatal and neonatal mortality outcomes

Improvements in mortality outcomes are the ultimate goal of these schemes, but in this review we did not identify any robust evaluations of impact on mortality outcomes; most of the studies we included were cross-sectional or before and after studies, plus one controlled study but without randomisation. Although the MMR in general in South Asia is slowly improving,Citation19 reports suggest only modest improvements in maternal mortality as a result of the Janani Suraksha Yojana scheme, but this should be interpreted as suggestive of the scheme's potential to impact on mortality, rather than proof that it is effective.Citation14 Indeed, there are concerns that the huge scale of such demand-side financing schemes may be diverting attention and funds away from other worthy maternal health initiatives. Elsewhere in the region, evidence for the impact on mortality is inconclusive, particularly since it is difficult to distinguish the impact of the schemes from general investment in maternal health (for example, in improvements to emergency obstetric care facilities).Citation1 As MMR is difficult to measure accurately without vital statistics, skilled attendance at birth has proven a popular proxy indicator of improvements in maternal health, with governments eager to show progress toward MDG 5.Citation52 In reality, this leaves us with a narrow conception of maternal health, disregarding stillbirths, miscarriage or induced abortion.Citation52

Conclusions

Several important questions remain. In the public sector, key questions include the implications of delivering the schemes through parallel structures to health directorates and whether regular government funding might be directed and used more efficiently. In the private sector, it is unclear whether the schemes are successful in attracting and involving providers and whether competition has any influence over quality of care. Where schemes are funded extensively through donor support, sustainability is a key concern, as is the uncertainty that comes with never knowing how long these schemes will continue. Importantly, our review highlights problems with targeting the poor, especially in universal schemes, and this could be overcome in part by involving communities and specific target groups in their design. At present there is a lack of depth and breadth in the evidence base of what has been measured.

A key question for future research is to what extent demand-side financing schemes for maternal health care meet the needs of women. The answer is not always obvious, and women themselves are rarely consulted. Research that uses qualitative methods to explore women's and family members' views and experiences of these schemes will help to understand what is important to women in choosing where to seek care and deliver their babies. Future research should also provide rigorous evaluation of the quality of care provided by public and private facilities participating in the schemes. Focussing solely on raising demand will not, in itself, reduce maternal mortality or morbidity, and it is prudent to remember that skilled attendance at birth should not be the only indicator of improvements in maternal health. Indeed, poor quality of care in facilities should place a question mark over this assumption.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge support from the European Union FP7 MATIND project.

Notes

References

- J Schmidt, T Ensor, A Hossain. Vouchers as demand side financing instruments for health care: a review of the Bangladesh maternal voucher scheme. Health Policy. 96: 2010; 98–107.

- S Agha. Impact of a maternal health voucher scheme on institutional delivery among low income women in Pakistan. Reproductive Health. 8: 2011; 10.

- T Ensor, S Clapham, DP Prasai. What drives health policy formulation: insights from the Nepal maternity incentive scheme?. Health Policy. 90: 2009; 247–253.

- I Anwar, M Sami, N Akhtar. Inequity in maternal health-care services: evidence from homebased skilled-birth-attendant programmes in Bangladesh. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 86(4): 2008; 252–259.

- A Kesterton, J Cleland, A Sloggett. Institutional delivery in rural India: the relative importance of accessibility and economic status. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 10(30): 2010; 1–9.

- PK Pathak, A Singh, SV Subramanian. Economic inequalities in maternal health care: prenatal care and skilled birth attendance in India, 1992–2006. PLoS One. 5(10): 2010; 1–17.

- M Lagarde, A Haines, N Palmer. The impact of conditional cash transfers on health outcomes and use of health services in low and middle income countries (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 4. At: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD008137/pdf. Accessed 15 October 2011.

- S Ahmed, M Khan. Is demand-side financing equity enhancing? Lessons from a maternal health voucher scheme in Bangladesh. Social Science & Medicine. 72(10): 2011; 1704–1710.

- I Anderson, H Axelson, B-K Tan. The other crisis: the economics and financing of maternal, newborn and child health in Asia. Health Policy and Planning. 26: 2011; 288–297.

- World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory Data Repository 2011. At: http://apps.who.int/ghodata/. Accessed 28 October 2011.

- Hussein J, Bell J, Dar lang M, et al. An appraisal of the maternal mortality decline in Nepal. PLoS ONE 6(5): e19898. doi:10.1371/ journal.pone.0019898.

- T Powell-Jackson, J Morrison, S Tiwari. The experiences of districts in implementing a national incentive programme to promote safe delivery in Nepal. BMC Health Services Research. 9: 2009; 97.

- S Witter, S Khadka, H Nath. The national free delivery policy in Nepal: early evidence of its effects on health facilities. Health Policy and Planning. 26: 2011; ii84–ii91.

- S Lim, L Dandona, J Hoisington. India's Janani Suraksha Yojana, a conditional cash transfer programme to increase births in health facilities: an impact evaluation. Lancet. 375: 2010; 2009–2023.

- P Chatterjee. India's government aims to improve rural health. Lancet. 28;368(9546): 2006; 1483–1484.

- P Bhate-Deosthali, R Khatri, S Wagle. Poor standards of care in small, private hospitals in Maharashtra, India: implications for public–private partnerships for maternity care. Reproductive Health Matters. 19(37): 2011; 32–41.

- International Institute for Population Sciences: National Family Health Survey (NFHS-1), 1992–93: India. 1995; IIPS: Mumbai. At: http://www.nfhsindia.org/. Accessed 25 January 2012.

- International Institute for Population Sciences. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005–6: India. 2007; IIPS: Mumbai. At: http://www.nfhsindia.org/. Accessed 25 January 2012.

- M Hogan, K Foreman, M Naghavi. Maternal mortality for 181 countries, 1980–2008: a systematic analysis of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 5. Lancet. 375(9726): 2010; 1609–1623.

- National Institute of Population Studies Pakistan, and Macro International. Demographic & Health Survey 2006–07. Islamabad: NIPS and Macro International. At: http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/FR200/FR200.pdf. Accessed 27 January 2012.

- National Institute of Population Studies, Pakistan and IRD/Macro International Inc. Demographic & Health Survey 1990–1991. Islamabad: NIPS and IRD/Macro International. At: http://measuredhs.com/publications/publication-fr29-dhs-final-reports.cfm. Accessed 27 January 2012.

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs. United Nations Statistics Division. At: http://mdgs.un.org/unsd/mdg/Data.aspx. Accessed 26 January 2012.

- World Health Organization. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2008. At: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/monitoring/9789241500265/en/index.html. Accessed 4 February 2012.

- P McNamee, L Ternant, J Hussein. Barriers in accessing maternal health care: evidence from low- and middle-income countries. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research. 9(1): 2009; 41–48.

- T Ensor, S Cooper. Overcoming barriers to health service access: influencing the demand side. Health Policy and Planning. 19(2): 2004; 69–79.

- S Thaddeus, D Maine. Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Social Science and Medicine. 38(8): 1994; 1091–1110.

- J Borghi, T Ensor, BD Neupane. Financial implications of skilled attendance at delivery in Nepal. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 11(2): 2006; 228–237.

- U Rob, M Rahman, B Bellows. Evaluation of the impact of the voucher and accreditation approach on improving reproductive behaviours and RH status: Bangladesh. BMC Public Health. 11: 2010; 257.

- S Ahmed, M Khan. A maternal health voucher scheme: what have we learned from the demand-side financing scheme in Bangladesh?. Health Policy and Planning. 26: 2011; 25–32.

- VK Paul. India: conditional cash transfers for in-facility deliveries. Lancet. 375(9730): 2010; 1943–1944.

- JE Lawn, K Kerber, C Enweronu-Larya. Newborn survival in low resource settings – are we delivering?. BJOG. 116(Suppl. 1): 2009; 49–59.

- A George. Persistence of high maternal mortality in Koppal District, Karnataka, India: observed service delivery constraints. Reproductive Health Matters. 15(30): 2007; 91–102.

- A Rath, I Basnett, C Cole. Improving emergency obstetric care in a context of very high maternal mortality: the Nepal Safer Motherhood Project 1997–2004. Reproductive Health Matters. 15(30): 2007; 72–80.

- C Barker, C Bird, A Pradhan. Support to the Safe Motherhood Programme in Nepal: an integrated approach. Reproductive Health Matters. 15(30): 2007; 81–90.

- C Bhusal, S Singh, R BC. Effectiveness and efficiency of Aama Surakshya Karyakram in terms of barriers in accessing maternal health services in Nepal. Journal of Nepal Health Research Council. 9(19): 2011; 129–137.

- T Powell-Jackson, BD Neupane, S Tiwari. Evaluation of the Safe Delivery Incentive Programme: Final Report of the Evaluation. 2008. At: http://www.safemotherhood.org.np/pdf/106Final_SDIP_Evaluation_Report.pdf. Accessed 29 October 2011.

- T Powell-Jackson, BD Neupane, S Tiwari. The impact of Nepal's national incentive programme to promote safe delivery in the district of Makwanpur. Innovations in Health System Finance in Developing and Transitional Economies (Advances in Health Economics and Health Services Research). 21: 2009; 221–249.

- Government of Nepal. Support to Safe Motherhood Programme, Nepal: Bi-annual Report. At: http://www.safemotherhood.org.np/pdf/149Biannual%20report%20final%205%20March%2009.pdf. Accessed 12 February 2012.

- B Subha Sri, N Sarojini, R Khanna. An investigation of maternal deaths following public protests in a tribal district of Madhya Pradesh, central India. Reproductive Health Matters. 20(39): 2012; 11–20.

- UN Population Fund India. Concurrent assessment of Janani Suraksha Yojana scheme in selected states of India: Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh. 2009; UNFPA India: New Delhi, 1–59.

- Government of India. Janani Suraksha Yojana: features and frequently asked questions and answers. 2006. At: http://jknrhm.com/PDF/JSR.pdf. Accessed 11 October 2011.

- D Mavalankar, A Singh, SR Patel. Saving mothers and newborns through an innovative partnership with private sector obstetricians: Chiranjeevi scheme of Gujarat, India. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 107(3): 2009; 271–276.

- R Bhat, D Mavalankar, PV Singh. Maternal healthcare financing: Gujarat's Chiranjeevi Scheme and its beneficiaries. Journal of Health, Population & Nutrition. 27(2): 2009; 249–258.

- Government of Gujarat. Chiranjeevi Yojana: Operational Mechanisms of the Scheme. 2012. At: www.gujhealth.gov.in/operational-scheme.htm. Accessed 10 February 2012.

- A Singh, D Mavalankar, R Bhat. Providing skilled birth attendants and emergency obstetric care to the poor through partnership with private sector obstetricians in Gujarat, India. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 87(12): 2009; 960–964.

- K Vora, D Mavalankar, K Ramani. Maternal health situation in India: a case study. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition. 27(2): 2009; 184–201.

- A Acharya, P McNamee. Assessing Gujarat's ‘Chiranjeevi’ Scheme. Economic & Political Weekly. 44(48): 2009; 13–15.

- H Nguyen. Encouraging maternal health service utilization: an evaluation of the Bangladesh voucher program. Social Science & Medicine. 74: 2012; 989–996.

- TLP Koehlmoos, A Ashraf, H Kabir. Rapid assessment of demand-side financing in Bangladesh, ICDDR,B Working Paper 170. 2008; Dhaka.

- B Hamid, S Kazmi, R Eichler. Pay for Performance: Improving Maternal Health Services in Pakistan. September. 2009; Health Systems 20/20 project, Abt Associates Inc.: Bethesda, MD.

- N Bellows, B Bellows, C Warren. The use of vouchers for reproductive health services in developing countries: systematic review. Journal of Tropical Medicine and International Health. 16(1): 2011; 84–96.

- B Austveg. Perpetuating power: some reasons why reproductive health has stalled. Reproductive Health Matters. 19(38): 2011; 26–34.