Abstract

Partnerships between civil society groups campaigning for reproductive and human rights, health professionals and others could contribute more to the strengthening of health systems needed to bring about declines in maternal deaths in Africa. The success of the HIV treatment literacy model developed by the Treatment Action Campaign in South Africa provides useful lessons for activism on maternal mortality, especially the combination of a right-to-health approach with learning and capacity building, community networking, popular mobilisation and legal action. This paper provides examples of these from South Africa, Botswana, Kenya and Uganda. Confidential enquiries into maternal deaths can be powerful instruments for change if pressure to act on their recommendations is brought to bear. Shadow reports presented during UN human rights country assessments can be used in a similar way. Public protests and demonstrations over avoidable deaths have succeeded in drawing attention to under-resourced services, shortages of supplies, including blood for transfusion, poor morale among staff, and lack of training and supervision. Activists could play a bigger role in holding health services, governments, and policy-makers accountable for poor maternity services, developing user-friendly information materials for women and their families, and motivating appropriate human resources strategies. Training and support for patients' groups, in how to use health facility complaints procedures is also a valuable strategy.

Résumé

Les partenariats entre les groupes de la société civile qui militent pour les droits de l'homme et les droits génésiques, les professionnels de la santé et d'autres pourraient contribuer davantage au renforcement des systèmes de santé requis pour réduire les décès maternels en Afrique. Le succès du modèle de connaissances de base sur le traitement du VIH mis au point par la Treatment Action Campaign en Afrique du Sud donne de précieuses leçons à ceux qui luttent contre la mortalité maternelle, en particulier l'association d'une approche du droit à la santé avec l'éducation et le renforcement des capacités, la création de réseaux communautaires, la mobilisation populaire et les mesures juridiques. L'article décrit certaines de ces activités en Afrique du Sud, au Botswana, au Kenya et en Ouganda. Des enquêtes confidentielles sur les décès maternels peuvent être des outils puissants pour le changement, si des pressions sont exercées pour donner suite à leurs recommandations. On peut utiliser de la même manière les rapports parallèles présentés aux organes des droits de l'homme des Nations Unies pendant les évaluations des pays. Les manifestations publiques pour protester contre des décès évitables ont réussi à mettre en lumière le manque de ressources des services, la pénurie de fournitures, y compris de sang pour les transfusions, la démoralisation du personnel, et le manque de formation et de supervision. Les militants pourraient jouer un rôle plus actif pour rendre les services de santé, les gouvernements et les décideurs comptables de la mauvaise qualité des services de maternité, préparer du matériel informatif adapté aux femmes et aux familles, et prôner des stratégies appropriées de ressources humaines. Il serait aussi utile de former les groupes de patientes et de les aider à utiliser les procédures de plainte contre les centres de santé.

Resumen

Las alianzas entre grupos de la sociedad civil que abogan por los derechos reproductivos yhumanos, profesionales de la saludy otras personas podrían contribuir más a fortalecer los sistemas de salud necesarios para lograr disminuir las tasas de mortalidad materna en Ãfrica. El éxito del modelo de educación sobre el tratamiento del VIH, creado por la Campaña de Acción para el Tratamientoen Sudáfrica,ofrece lecciones útiles para el activismo relacionado con la mortalidad materna, especialmente la combinación de un enfoque de derecho a la saludcon el desarrollo de conocimientos y capacidad, la creación de redes de contactos comunitarios, movilización popular y acción jurídica. En este artículo se exponen ejemplos de estas lecciones en Sudáfrica, Botsuana, Kenia y Uganda. Las investigaciones confidenciales de muertes maternas pueden ser poderosos instrumentos para realizar cambios si se ejerce presión para que se sigan sus recomendaciones. Los informes sombra presentados durante las evaluaciones realizadas por las Naciones Unidasde los derechos humanosen esos países se pueden utilizar de manera similar. Las protestas y manifestaciones públicas respecto a muertes evitables han logrado llamar la atención a servicios con escasos recursos, escasez de insumos como sangre para transfusiones, moral bajaentre el personaly falta de capacitación y supervisión. Los activistas podrían desempeñar un mayor papel en imputara los servicios de salud, gobiernos y formuladores de políticasla responsabilidad de los deficientes servicios de maternidad, elaborar materiales informativos fáciles de utilizar para las mujeres y familias, y motivarestrategias con recursos humanos correspondientes. Otra estrategia valiosa es capacitar y apoyar a los grupos de pacientes en el uso de los procedimientos para presentar querellas en las unidades de salud.

Partnerships between health professionals and civil society organisations have been recognised as an essential catalyst for health systems strengthening and have contributed significantly to improvements in programme delivery in many sectors. In a recent landmark publication, Frenk et al called for a global social movement, engaging all stakeholders and linking together educational institutions with networks and alliances, including with governments and civil society organisations, to build new relationships in health systems.Citation1 A good example of how this has worked internationally is of HIV campaigners, who have challenged research and health institutions, pharmaceutical companies, funding bodies, politicians and policy-makers to take their issues seriously, gone to court to demand constitutional rights to health care for people living with HIV, and been instrumental in achieving affordable antiretroviral treatment for so many, even in poorer countries.

With regard to maternal mortality, where the majority of deaths are preventable and in many countries occur in health institutions, there are opportunities to learn from the successes of HIV campaigns in making health services more responsive to women's needs. Operational research on maternity services in South Africa has identified the need for stronger, better coordinated health systems, development of a culture of organisational learning, and training for problem-solving as teams, with incentives for good management and supportive supervision.Citation2 This discussion paper looks at how activism can motivate for some of these to happen, using examples of campaigns in diverse situations for the prevention of maternal mortality, with lessons that may be useful for the African context, where the least progress has been made in reducing maternal deaths.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), countries that have succeeded in making childbirth safer for women have three factors in common.Citation3 First, policy-makers and managers have identified ways of approaching the problem and acted on that knowledge. Second, the focus has been on provision of care (including emergency care) by skilled nurse-midwives and doctors at and after childbirth for all women, in addition to antenatal care. Third, access to the necessary resources, financial and geographical, has been guaranteed for the entire population. Thus, information, commitment, universal access and professionalisation of service providers are essential for positive outcomes. In most of Africa, decisions about how maternity services function remain the preserve of senior health professionals and government departments, which have not been sufficiently effective in resolving the underlying causes of maternal deaths. Partnerships between civil society organisations (CSOs) and health professionals could play a more active role in motivating change.

Patient-centred care and human rights

Frenk et al advocate for health system reforms that emphasise patient and population-centredness, while recognising that poorer people are less able to make health services respond to their needs.Citation1 Historically, changes in abortion law, antenatal care and childbirth in high-income countries have resulted from pressure from coalitions of women's organisations, health and legal professionals, parliamentarians and policy-makers, working together for the common goal of making childbirth safer and improving quality of care.Citation4 The Changing Childbirth Initiative in the UK, adopted as government policy in 1994, aimed to ensure that maternity services were accessible, responsive and effective. Because of proposed changes to the policy agenda by politically savvy patient representative groups and women legislators, substantial women-centred changes to services were made.Citation5 Quality of care and patient satisfaction indicators are now standard in audit tools used by health professionals in monitoring maternity services in the UK,Citation6 but continued active scrutiny by patient representative groups is required to ensure quality standards are met and sustained.Citation7

Failure to reduce preventable maternal deaths represents a violation of women's right to life, health, non-discrimination and equality. As signatories to international human rights conventions and to the Millennium Development Goals, States are obliged to provide the necessary services of sufficient quality to prevent these deaths. Use of a human rights frameworkCitation8 provides tools and strategies for holding governments, service providers and policy-makers accountable for these goals, including the use of courts to uphold them. Authorities and institutions need to be made aware that the public has a right to monitor, scrutinise and document progress or lack of it in achieving these goals, and in the interests of transparency, reports must be publicly available in accessible language and formats. These rights may seem obvious to some, but the right to health care, as articulated in these frameworks, is not intuitively understood by many health professionals, especially those who see health care as a commodity to be bought by those who can afford it. As Freedman reminds us:

“A rights-based approach… must be grounded in a careful critique of the workings of power that have permitted appalling rates of maternal death to remain unchanged… [P]olicy making is a deeply political process whose success in addressing health problems is necessarily dependent on a reading of the power dynamics that underlie a specific situation…being attuned to the underlying dynamics of something as seemingly nonpolitical as the presentation of data… [I]f we approach human rights as a tool for transforming a system...then a rights-based approach can make a meaningful difference for the decision makers compelled to make a real policy choice.” Citation9

The HIV treatment literacy model

The treatment literacy model,Citation10 developed by the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) in South Africa, could be useful for activist groups in working with health professionals to address the underlying causes of maternal deaths. TAC used a “right to health” approach to HIV through a combination of protest, popular mobilisation and legal action. They emphasised building capacity among affected people, prioritising those who were disadvantaged, and through the cornerstone concept of treatment literacy. HIV education materials and methods were developed, including on the benefits and side-effects of treatment, embedded in the science of medicine, the political context, human rights, equity of access to health care, and the duties of governments. People living with HIV learned skills in asking questions of their health care providers in non-confrontational ways, so that they became partners in their treatment rather than passive and uninformed recipients. After training, TAC volunteers were attached to health facilities and community organisations to further extend campaign and education activities. They linked into TAC community networks and local organising activities, galvanising social mobilisation around access to treatment and care. A crucial part of this programme involved building self-worth and self-efficacy through the “HIV-positive” trademark, rejecting silent victimhood for people living with HIV. HIV support groups all over southern Africa received and benefited from treatment literacy training carried out by TAC.

The landmark campaign in which the government of South Africa was challenged over its failure to provide pregnant HIV-positive women with antiretroviral drugs that could have prevented the transmission of HIV to their infants, received national and international media coverage, also drawing attention to high prices charged by pharmaceutical companies to the detriment of poor people.Citation11 TAC continues to lobby governments, national and international funding and policy-making bodies for improved quality of health care in South Africa and universal access to antiretroviral treatment.

Implementing recommendations from confidential enquiries

The Treatment Action Campaign attributed rising maternal mortality in southern Africa to HIV, emphasising the need for pregnant women with HIV to be on antiretrovirals and also warning that certain antiretrovirals exacerbate anaemia, putting HIV-positive women at higher risk of complications if they have heavy bleeding at childbirth. Although HIV contributes to nearly half of maternal deaths in South Africa,Citation12 the underlying reasons for death are still haemorrhage and sepsis, preventable through timely and early intervention. Following the publication of the National Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths 2002–2004 in South Africa in 2006, TAC made the following statement:

“The [Enquiry] is a call to action. It will be the job of civil society to monitor that the Department of Health starts implementing these recommendations. If the Department continues to fail to implement them, then mass mobilisation and the courts will be needed to ensure that the Constitutional rights to health-care of women are met.” Citation13

In May 2011, hundreds of concerned citizens and health professionals stormed the Constitutional Court in Kampala, Uganda, protesting the deaths of women in childbirth, in support of a coalition of activists who have taken out a landmark lawsuit against the government over two women who bled to death giving birth unattended in hospital.Citation14,15 The Centre for Health, Human Rights and Development (CEHURD), a Ugandan NGO, and the families of the two deceased women argued:

“…by not providing essential medical commodities and health services to pregnant women, the government is violating the constitutional rights of Ugandans, including the right to health, the right to life, and the rights of women.”

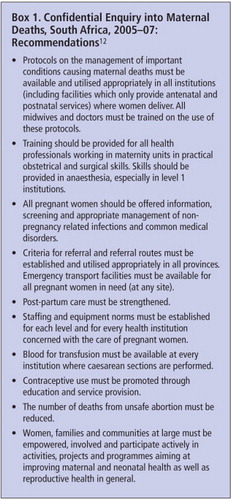

The combination of factors that contribute to maternal deaths flag fundamental health system failings and can seem so complex that it is hard to know how to start the chain of actions to address them. Confidential enquiries are potentially powerful instruments of change since they provide details of how maternal deaths occur, but only if the recommendations made by the reports are acted on, and for the whole population at risk. Reports of confidential enquiries in the UK, published triennially since 1952, made a significant impact on prevention of maternal mortality and morbidity and were emulated as models in other countries.Citation18 They target primarily the medical and midwifery professions, who have responded to the recommendations with increased training, supervision, guideline development and implementation, and outcome monitoring.

Although Botswana and South Africa have conducted national confidential enquiries, maternal deaths continue to take place in hospitals because governments are not addressing the systemic failures that contribute to them.Citation2,12,19–21 These include poor initial assessment and diagnosis of cases, especially at secondary level, failure to follow standard protocols at primary and secondary levels, inadequate monitoring of patients at all levels of care, poor clinical practices, inadequate supervision and lack of essential supplies.

Producing shadow reports for UN treaty monitoring bodies

States are obliged to report regularly on their progress in implementation of UN treaties and conventions to which they are signatories. In many countries, civil society organisations produce their own shadow reports, critiquing their government's progress, highlighting why objectives or targets are not being met. These reports are important first steps, but their production alone rarely triggers improvements and has to be accompanied by organised campaigns that showcase what changes are needed, who is answerable for these changes, and how resources can be prioritised for change. Public debate on priority-setting in health-resource allocation is essential. In Tanzania, government claims of staff training for emergency obstetric care and family planning, with ambulances prioritised for poorly performing areas, were not matched with improvements on the ground. Women were still delivering at home without trained birth attendants and utilisation of the health facilities did not increase. The 2008 NGO shadow report for the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) identified that the quality of information women were receiving was poor, but it did not indicate steps needing to be taken to improve this.Citation22 A Nigerian NGO shadow report for CEDAW, itemised point by point all the areas in which maternal health objectives could not be met because of failings in policy, legal and administrative areas,Citation23 again without any strategy for change.

Holding health professionals and the health system accountable

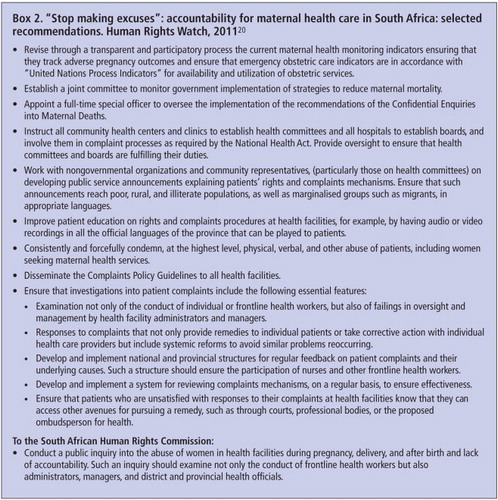

The commitment to professional competence and quality of care is a cornerstone of the code of practice for health professionals and managers, and yet in most of Africa they are rarely held to account for the standards of health care provided in the public sector.Citation24 Governments are accountable for the duty to create environments conducive for health staff to practice in a professional way. At the same time, health professionals should be accountable for the standard of care they provide, and for neglect or abuse of their patients. The Human Rights Watch report on South Africa detailed several instances of women in childbirth who had been neglected and disrespected by nursing staffCitation20 and made 35 recommendations, many suggesting how the complaints procedure should be improved and used to strengthen services (Box 2).

Similarly, a recent report of research in Kenya, co-authored by the Federation of Women Lawyers (FIDA) and the Center for Reproductive Rights (CRR), detailed the physical and verbal abuse suffered by women seeking reproductive health services, including detention in health facilities for inability to pay fees.Citation25 Public sector health workers were unable to provide adequate care because of poor institutional support and shortages of funding, medical staff and equipment. Hospitals lacked the most basic supplies, such as anaesthesia, gloves, syringes, surgical blades, soap, disinfectant, speculums, and bed linen. Patients were required to bring in their own supplies or do without, for instance having episiotomies stitched without anaesthetic. The report attributed the long-standing abuse, humiliation and discrimination described by women attending Pumwani Maternity Hospital, Kenya's largest public maternity hospital, to government failure to take responsibility for these human rights violations, lack of accountability within the health system, lack of awareness of patients' rights, and the absence of transparent and effective oversight mechanisms. The conditions in maternity services were quoted as one reason why women preferred to deliver at home.

Recommendations included strengthening structures and public awareness to educate and protect patients' rights; requiring health care facilities to establish formal complaints mechanisms as part of licensing requirements; strengthening complaints mechanisms at Medical Boards, professional associations and councils; improved training of health professionals; increased funding from the Government to provide for equipment and supplies; public education on the right to health, and provision of information to judges and legal professionals on rights violations in the health care context.

The report and recommendations were disseminated to relevant bodies through the media, advocacy workshops, meetings with health professional associations and other influential bodies. In response, the government removed user fees for maternity services in all public health institutions and also appointed a new head of Pumwani Maternity Hospital, someone experienced in a reproductive rights approach to maternal health. The midwives' association invited FIDA to provide training in a rights-based approach to service delivery, while the office of the Director of Public Prosecutions indicated that they would assist FIDA to prosecute cases involving such abuses.Citation26

Also in response to this report, the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights commenced a Public National Inquiry on Sexual and Reproductive Health in June 2011. This type of inquiry is ground-breaking not only for Kenya but regionally, the result of extensive advocacy by FIDA and CRR, including a petition calling for an official inquiry. The inquiry was conducted via country-wide public hearings, testimonials and expert forums, the report of which is currently being finalised.Citation27 The campaign is embedded within the work of Family Care International and the International Initiative on Maternal Mortality and Human Rights in Kenya, engaging health facility staff and management committees with communities to promote women's right to safe childbirth and respectful care. There is some evidence from this work that using a rights approach and encouraging partnerships between patient groups and health staff reduces disrespect and increases attention to quality of care.Citation28

Addressing skills and resource gaps

In 1996, the central public hospital in Nepal initiated a three-month training course for anaesthetist assistants who went on to provide anaesthesia for thousands of operations every year and were crucial for caesarean sections. Vigorous advocacy by Nepal's Safer Motherhood Network, an alliance of health professionals and NGOs, ensured that this cadre were accredited and reinstated after opposition from physicians had halted the programme.Citation29 Freedman argues that a clinical model in which only physician-anaesthetists conduct anaesthesia results in a far greater number of women dying in childbirth.Citation9 The same case can be made for obstetricians. Training non-physician clinicians as well as medical and nursing staff to provide better quality obstetric care is a way of increasing the number of skilled staff available, to prevent cases escalating to emergencies, and to respond swiftly when they do, improving outcomes.Citation30,31

Surgical and anaesthetic skills contribute significantly to reductions in maternal and child mortality but are in short supply in Africa.Citation32–34 For health facilities to manage obstetric emergencies correctly they need well-trained, well-supervised, skilled and equipped staff. In many African countries (Ethiopia, Mozambique, Malawi, Tanzania),non-physician clinicians have been successfully trained to carry out caesarean sections and provide anaesthesia for maternity cases.Citation35,36 In Uganda there are only 75 surgeons and 10 physician-anaesthetists to serve a population of 27 million people. Most surgery in rural district hospitals is carried out by non-specialist doctors with anaesthesia conducted by 350 non-physician anaesthetics officers who have 18 months of training to complement a high-school qualification.Citation37 In Mozambique in 2002, surgical technicians performed more than 90% of all major obstetric surgery in the rural areas, with clinical outcomes comparable to doctors.Citation38 Forty or so years of experience have demonstrated the cost-effectiveness and high level of performance of these cadres, and their importance for safe childbirth in rural areas of Africa.Citation35,36,39

Opposition to the scaling-up of training of non-physician clinicians by medical and nursing professional bodies, which previously limited access to safe childbirth in Africa,Citation35,40 is being overcome by clinical leadership and demonstration of improved outcomes, as in Ghana, Mozambique and Malawi.Citation39 As in the example of Nepal, civil society and health professional alliances could influence medical and nursing associations to have a wider vision of the whole health system, recognising the expert role of physicians and senior nurses as the trainers and supervisors of these valuable cadres.Citation30,39

Campaigning for voluntary blood donation

A very practical way that civil society can assist in prevention of maternal deaths is through mobilisation of volunteer blood donors from the public. Haemorrhage during childbirth tops the list of causes of maternal deaths in Africa and Asia,Citation41 and one review has attributed 26% of these deaths to lack of blood for transfusion.Citation42 Even in high-income countries blood supplies are lower than needed and blood transfusion services invest in campaigns that appeal to donors to “give now”, knowing that they or their families may need help at a later date and that society depends and thrives on reciprocal generosity. A customer-satisfaction approach is used to make people feel good about donating blood, paying attention to waiting times, staff attitudes, being open and accountable, seeking continuous improvement to the service, and responding in a timely manner to donor complaints.Citation43

The aim is to optimise donor loyalty and encourage regular donations 3–4 times a year, which is safer and more cost effective than recruiting new donors. Media campaigns to motivate blood donations in higher-income countries have become more direct and imaginative, mentioning maternal mortality both in the context of saving women's lives but also the importance to the newborn of the mother surviving. Media use stories of people who have donated blood in a very positive light, including events where recipients meet donors. The key is to raise donor profiles, to show them as something precious, to be nurtured, and to reward their volunteer spirit as socially responsible. Staff who do well are also given recognition. In the process, donors, health professionals and staff work in partnership to protect the lives of women in childbirth, publicly and passionately. Video clips on YouTube show recipients thanking donors for having saved their lives, thus giving the process a human face. One features the husband of a woman who was bleeding heavily during a caesarean section, who says:

“…when I heard the doctor on the phone saying he needed more blood and he needed it right then, it was a scary thing. My wife's life was in the balance… I am wondering what if someone at the end said: ‘Sorry, we don't have it right now’… it just became personal. I'm much more serious about it and I try and give blood every three months since then.” Citation44

The 14th of June is promoted by WHO and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies as World Blood Donor day, which aims to build a worldwide culture of voluntary (non-remunerated) blood donation and raise awareness of the need for blood donation. But one day of media attention and speeches is inadequate to create the culture change required. Many of the barriers to sufficient blood donations are local: non-existence of national blood transfusion services in many African countries, poor information about the whole process, for example unfounded beliefs of a risk of infection from donating blood, misconceptions about how the blood will be used, and fear of side effects and bewitching.Citation46 More intensive public education campaigns are needed to inform the public about blood donation, which could be provided by alliances between international institutions such as WHO in collaboration with local branches of the Red Cross and NGOs like Rotary Club.

The way forward

The scientific and technical knowledge of what works to reduce maternal mortality already exists alongside an understanding of why health systems in Africa are failing to serve their populations. Partnerships and allliances imply better collaboration and communication between communities, activists, health care staff and professionals, managers and so on. There is a wealth of ideas of what needs to be done, from public inquiries to community members being supported to sit on health facility committees. The TAC model shows the intensity of activism needed to campaign for and achieve change, which in itself needs adequate resourcing. Donor support for this kind of advocacy and activism has flagged and needs to be renewed and expanded. There are many excellent and ambitious campaigns taking place and opportunities for practical involvement in African communities and elsewhere, some described in this paper, that need to move to the next level in monitoring and sustained action for achieving accountability. What is clear is that far greater efforts and resources are required to make an impact on maternal deaths, and that the changes involved will strengthen the whole health sector.

References

- J Frenk, L Chen, ZA Bhutta. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 376(9756): 2010; 1923–1958.

- LS Thomas, R Jina, KS Tint. Making systems work.The hard part of improving maternal health services in South Africa. Reproductive Health Matters. 15(30): 2007; 38–49.

- The World Health Report 2005: Make every mother and child count. Chapter 4. At: www.who.int/whr/2005/chapter4/en/index2.html#3. Accessed 4 March 2012.

- M Berer. Making abortions safe: a matter of good public health policy and practice. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 78(5): 2000; 580–589.

- E Declercq. Changing childbirth in the United Kingdom: lessons from US Health Policy. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 23(5): 1998; 833–859.

- AM Buller, SF Murray. Monitoring access to maternity services in the UK: a basket of markers for local casenote audit. December. 2007; Florence Nightingale School of Nursing & Midwifery at King's College London.

- North of Tyne PPI Forums. Joint Maternity Services Report. January 2008 update. At: http://www.resourcebank.org.uk/resource/QRZAEYC4WKRF.PDF. Accessed 1 April 2012.

- Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on preventable maternal mortality and morbidity and human rights. (A/HRC/14/39). 2010; UNHRC: Geneva.

- LP Freedman. Shifting visions: ‘Delegation’ policies and the building of a ‘rights-based’ approach to maternal mortality. Journal of American Medical Women's Association. 57: 2002; 154–158.

- M Heywood. South Africa's Treatment Action Campaign: combining law and social mobilization to realize the right to health. Journal of Human Rights Practice. 1(1): 2009; 14–36.

- GJ Annas. The right to health and the nevirapine case in South Africa. New England Journal of Medicine. 348: 2003; 750–754.

- NCCEMD. Saving Mothers 2005-2007: Fourth Report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in South Africa. www.doh.gov.za/docs/reports/2007/savingmothers.pdf

- Treatment Action Campaign. At: www.tac.org.za/documents/AnalysisOfMaternalDeaths. Accessed 4 March 2012.

- Anthony Wesaka. Sunday Monitor, 29 May 2011. At: www.monitor.co.ug/News/National/-/688334/1170928/-/c0y7y1z/-/index. Accessed 4 March 2012.

- Uganda sued over maternal deaths. Al Jazeera, 21 October 2011. At: www.aljazeera.com/video/africa/2011/10/2011102153513144350. Accessed 4 March 2012.

- CEHURD. Constitutional court begins hearing maternal deaths case. At: www.cehurd.org/2011/09/constitutional-court-begins-hearing-maternal-deaths-case-3. Accessed 4 March 2012.

- The Maternal Health Coalition waits for judges in vain. 15 November 2011. At: http://www.cehurd.org/2011/11/the-maternal-health-coalition-waits-for-judges-in-vain. Accessed 4 March 2012.

- WD Ngan Kee. Confidential enquiries into maternal deaths: 50 years of closing the loop [Editorial]. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 94(4): 2005; 413–416.

- KD Mogobe, W Tshiamo, M Bowelo. Monitoring maternal mortality in Botswana. Reproductive Health Matters. 15(30): 2007; 163–171.

- Human Rights Watch. Stop making excuses: accountability for maternal health care in South Africa. August 2011.

- World Bank. Reproductive health at a glance: Botswana, May 2011. At: www.worldbank.org/VPX2ANTTWO

- Tanzania NGO shadow report to CEDAW. At: www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/cedaw/docs/ngos/WLACTanzania41.pdf. Accessed 5 March 2012.

- The Nigerian NGO Coalition shadow report to the CEDAW Committee. At: www.fidh.org/IMG/pdf/BAOBABNigeria41.pdf. Accessed 4 March 2012.

- AK Rowe, D de Savigny, CF Lanata. How can we achieve and maintain high-quality performance of health workers in low-resource settings. Lancet. 366(9490): 2005; 1026–1035.

- Center for Reproductive Rights; Federation of Women Lawyers–Kenya. Failure to Deliver – Violations of Womens' Human Rights in Kenyan Health Facilities. 2007; FIDA: Nairobi, Kenya.

- Ogangah C. Gender and Right to Reproductive Health. Health and Human Rights Workshop Report, 23–24 April, 2008. Health NGO Network (HENNET). Nairobi, Kenya.

- Mariam Kamunyu, Transformative Justice Programme, Federation of Women Lawyers Kenya (FIDA Kenya). Personal communication, 27 September 2011.

- D Bowser, K Hill. Exploring evidence for disrespect and abuse in facility-based childbirth. Report of a landscape analysis. 2010; USAID-TRAction Project: Harvard School of Public Health University Research.

- M Zimmerman, M Lee, S Retnaraj. Non-doctor anaesthesia in Nepal: developing an essential cadre. Tropical Doctor. 38: 2008; 148–150. DOI: 10.1258/td.2008.080062.

- S Lobis, G Mbaruku, F Kamwendo. Expected to deliver: alignment of regulation, training, and actual performance of emergency obstetric care providers in Malawi and Tanzania. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 115: 2011; 322–327.

- D Mavalankar, V Sriram. Provision of anaesthesia services for emergency obstetric care through task shifting in South Asia. Reproductive Health Matters. 17(33): 2009; 21–31.

- D Ozgediz, R Riviello. The “other” neglected diseases in global public health: surgical conditions in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS Med. 5(6): 2008; 850–854.e121.

- M Cherian, S Choo, I Wilson. Building and retaining the neglected anaesthesia health workforce: is it crucial for health systems strengthening through primary health care?. 2010; Bulletin of WHO. DOI: 10.2471/BLT.09.072371.

- AL Kushner, MN Cherian, L Noel. Addressing the Millennium Development Goals from a surgical perspective: essential surgery and anaesthesia in 8 low- and middle- income countries. Archives of Surgery. 145(2): 2010; 154–159.

- F Mullan, S Frehywot. Non-physician clinicians in 47 sub-Saharan African countries. Lancet. 370(9605): 2007; 2158–2163.

- S Fonn, S Ray, D Blaauw. Innovation to improve health care provision and health systems in sub-Saharan Africa - promoting agency in mid-level workers and district managers. Global Public Health. 6(6): 2011; 657–668.

- SC Hodges, C Mijumbi, M Okello. Anaesthesia services in developing countries: defining the problems. Anaesthesia. 62: 2007; 4–11.

- C Pereira, A Cumbi, R Malalane. Meeting the need for emergency obstetric care in Mozambique: work performance and histories of medical doctors and assistant medical officers trained for surgery. British Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 114: 2007; 1530–1533.

- D Dovlo. Using mid-level cadres as substitutes for internationally mobile health professionals in Africa. A desk review. Human Resources for Health. 2: 2004; 7.

- JPdeV van Niekerk. Mid-level workers: high-level bungling?. South Africa Medical Journal. 96: 2006; 1209–1211.

- World Health Organization. Reproductive health indicators: guidelines for their generation, interpretation and analysis for global monitoring. 2006; WHO: Geneva.

- I Bates, GK Chapotera, S McKew. Maternal mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: the contribution of ineffective blood transfusion services. British Journal Obstetrics Gynaecology. 115(11): 2008; 1331–1339.

- A Young. Responding to blood donor feedback. March 2009. At: www.nhsbt.nhs.uk/downloads/board_papers/mar09/responding_to_blood_donor_feedback_09_26.pdf

- You Tube. The gift of life, a love story about blood. At: www.youtube.com/watch?v=gtruMhwo5TM

- Motswagole T, Jammalamadugu S, Josiah L. Personal communication, Gaborone. August 2011.

- IRIN. Why the beleaguered hospitals of South Sudan are out for blood. At: http://www.guardian.co.uk/global-development/2012/jan/31/south-sudan-hospitals-blood/print. Accessed 5 February 2012.