Abstract

Abstract

With the expansion of routine antenatal HIV testing, women are increasingly discovering they are HIV-positive during pregnancy. While several studies have examined the impact of HIV on childbearing in Africa, few have focused on the antenatal/postpartum period. Addressing this research gap will help tailor contraceptive counseling to HIV-positive women’s needs. Our study measures how antenatal HIV diagnosis affects postpartum childbearing desires, adjusting for effects of HIV before diagnosis. A baseline survey on reproductive behavior was administered to 5,284 antenatal clients before they underwent routine HIV testing. Fifteen months later, a follow-up survey collected information on postpartum reproductive behavior from 2,162 women, and in-depth interviews with 25 women investigated attitudes toward HIV and childbearing. HIV diagnosis was associated with a long-term downward adjustment in childbearing desires, but not with changes in short-term postpartum desires. The qualitative interviews identified health concerns and nurses’ dissuasion as major factors discouraging childbearing post-diagnosis. At the same time, pronatalist social norms appeared to pressure women to continue childbearing. Given the potential for fertility desires to change following antenatal HIV diagnosis, contraceptive counseling should be provided on a continuum from antenatal through postpartum care, taking into account the conflicting pressures faced by HIV-positive women in relation to childbearing.

Resumé

Avec l’expansion du dépistage prénatal systématique du VIH, les femmes apprennent de plus en plus souvent qu’elles sont séropositives pendant leur grossesse. Plusieurs études ont examiné l’impact du VIH sur le choix d’avoir des enfants en Afrique, mais rares sont celles qui sont centrées sur la période prénatale et du post-partum. Combler cette lacune aidera à concevoir des conseils de contraception adaptés aux besoins des femmes séropositives. Notre étude évalue l’incidence du diagnostic prénatal de la séropositivité sur le désir de maternité pendant le post-partum, en tenant compte des effets du VIH avant le diagnostic. Une enquête de référence sur le comportement génésique a été administrée à 5284 patientes des services prénatals avant de les tester pour le VIH. Quinze mois plus tard, une enquête de suivi a recueilli des informations sur le comportement génésique post-partum de 2162 femmes, et des entretiens approfondis avec 25 femmes ont étudié leurs attitudes vis-à-vis du VIH et de la maternité. Le diagnostic de la séropositivité était associé à un ajustement à la baisse à long terme du désir d’enfants, mais pas à des changements du post-partum à court terme. D’après les entretiens qualitatifs, les préoccupations de santé et la dissuasion des infirmières étaient les principaux facteurs décourageant la maternité après le diagnostic. En même temps, les normes sociales pronatalistes semblaient inciter les femmes à continuer d’avoir des enfants. Étant donné le potentiel de modification des désirs de fécondité après le diagnostic prénatal de la séropositivité, des conseils contraceptifs devraient être prodigués en continuité depuis les visites prénatales jusqu’au post-partum, en tenant compte des pressions conflictuelles qui s’exercent sur les femmes séropositives face à la maternité.

Resumen

Con el aumento en las pruebas de VIH prenatales de rutina, cada vez más las mujeres descubren que son VIH-positivas durante el embarazo. Aunque varios estudios han examinado el impacto del VIH en tener hijos en Ãfrica, pocos se han centrado en el período prenatal/posparto. Llenar esta brecha ayudará a adaptar la consejería anticonceptiva a las necesidades de las mujeres VIH-positivas. Nuestro estudio mide cómo el diagnóstico prenatal del VIH afecta los deseos de tener hijos posparto, ajustándose a los efectos del VIH antes del diagnóstico. Se administró una encuesta de base sobre el comportamiento reproductivo prenatal a 5284 mujeres antes de realizar las pruebas de VIH de rutina. Quince meses después, una encuesta de seguimiento recolectó datos sobre el comportamiento reproductivo posparto de 2162 mujeres y las entrevistas a profundidad con 25 mujeres investigaron las actitudes hacia el VIH y la maternidad. El diagnóstico de VIH se asoció con un ajuste descendente a largo plazo en los deseos de tener hijos, pero no con cambios en los deseos posparto a corto plazo. Las entrevistas cualitativas identificaron las inquietudes respecto a la salud y la disuasión de las enfermeras como importantes factores que desaniman a las mujeres a tener hijos después del diagnóstico, mientras que las normas sociales pronatalistas parecieron presionar a las mujeres a continuar teniendo hijos. Debido al potencial de que los deseos relacionados con la fertilidad cambien después del diagnóstico prenatal del VIH, se debe ofrecer consejería anticonceptiva desde el período prenatal hasta el posparto, tomando en cuenta las presiones conflictivas que enfrentan las mujeres VIH-positivas con relación a la maternidad.

In Tanzania’s Mwanza region, HIV prevalence among women of reproductive age is 7%.Citation1 HIV-positive women therefore make up a sizeable proportion of pregnant women. In a region where over a quarter of pregnancies are unwanted or mistimed,Citation2 meeting the reproductive and contra ceptive needs of HIV-positive women is critical to their rights and health, will help avoid unwanted pregnancies,Citation3 and is a cost-effective way to prevent HIV-positive births.Citation4 Meeting these needs requires a thorough understanding of HIV-positive women’s childbearing behavior and desires, and the impact of an HIV-positive diagnosis on these variables.

For many women in Africa, HIV diagnosis is increasingly occurring during pregnancy. In Tanzania, provider-initiated HIV testing is a routine part of antenatal care in clinics with appropriate facilities, with the aim of identifying women in need of prevention of mother-to-child transmission services. At the time of this study (2008), the great majority of pregnant women in Mwanza region had never had an HIV test before.Citation1 Although HIV testing is rapidly expanding, many women are still discovering they are HIV-positive during pregnancy. In order to adequately address their reproductive and contraceptive needs after diagnosis, it is crucial to examine the specific impact of antenatal HIV diagnosis on childbearing behavior and desires, particularly in the postpartum period, which is likely to be different from other times. This can help inform HIV and contraceptive counseling guidelines for use during antenatal and postpartum care following an HIV-positive diagnosis.

Several recent studies in sub-Saharan Africa have examined the impact of HIV diagnosis on reproductive behavior, finding that an HIV-positive diagnosis tends to decrease childbearing desires.Citation5–9 However, only a handful of studies have focused on the impact of antenatal diagnosis on postpartum fertility desires,Citation10–12 and none of these have taken into account baseline differences in reproductive behavior between HIV-positive and HIV-negative women prior to HIV testing. Yet there is strong evidence from numerous studies that HIV-positive and HIV-negative women have significant differences in reproductive behavior and intentions even before diagnosis, mediated by both biological and behavioral mechanisms, often resulting in lower fertility in HIV-positive women. For example, HIV-positive women may have decreased fecundity or reduced coital frequency due to illness.Citation13–15 Research that does not take these baseline differences into account risks over-or underestimating the effect of HIV diagnosis on childbearing. This study bridges this gap by investigating the differences in childbearing desires between HIV-negative and HIV-positive women after antenatal HIV testing, controlling for pre-test differences in reproductive behavior. It also presents a qualitative analysis of interviews with 25 postpartum study participants to provide further insight into women’s attitudes towards HIV and childbearing. In this paper, “postpartum” refers to the “extended postpartum period,” defined as the first year after giving birth.Citation16

Methodology

From January to May 2008, a baseline survey of 5,284 pregnant women was carried out in 15 antenatal clinics offering HIV testing in two districts of Mwanza region, including both highly urbanized areas and remote rural areas. The 15 clinics surveyed represented all government clinics offering HIV testing in the catchment area at the time, and all women attending these clinics during the survey period were invited to participate. The study sample therefore constituted the complete population of antenatal attendees in the catchment area during the study period.

All antenatal attendees were asked for their informed consent to participate in the survey, and 5,284 (99.6%) consented. Of these, 5,121 (97%) agreed to an HIV test. Nurses from each clinic (who were also HIV counselors) were trained to administer a standardized questionnaire to women prior to HIV testing and counseling. The questionnaire collected information on socio-demographic characteristics, childbearing and contraceptive history, and childbearing desires. If respondents agreed to be contacted 15 months later for a follow-up interview, their contact details were recorded on a separate form linked to their questionnaire by an anonymous study number. After the baseline interview, respondents received HIV counseling and testing. Subject to their consent, HIV test results were linked to survey answers using the same study numbers.

Of the 5,121 baseline respondents who had an HIV test, 4,850 (95%) consented to being contacted for a follow-up survey, of whom 2,166 (45%) were successfully contacted and 2,162 were actually interviewed. Respondents were contacted by fieldworkers from each community 15 months after their baseline interview, and were invited for a follow-up interview at the clinic. The follow-up questionnaire was administered by the same nurses as at baseline. Using the same location and interviewers for the baseline and follow-up interviews helped increase the comparability of responses in our before/after study design. The follow-up questionnaire used a calendar tool to record data on pregnancies, sexual activity and contraceptive use for each month postpartum up until the interview. It also collected information on childbearing desires at that time. The follow-up data were linked to respondents’ baseline data using the same study numbers.

There are many ways to define childbearing desires as distinct from intentions.Citation17 We define “desire” as the feeling associated with “wanting” a child: the question asked in both baseline and follow-up surveys was, “Do you want another child [after this one]?” “Intending” to have another child might differ considerably from “wanting” because of how respondents evaluate the different factors affecting their childbearing plans, and we acknowledge that desires may not ultimately translate into intentions or actual behavior. We were interested in how HIV diagnosis affects desire for a child as an outcome in its own right, regardless of the extent to which this desire might predict subsequent behavior, because these desires are likely to form the basis of personalized reproductive and contraceptive counseling. We therefore consider childbearing desires and ideal family size as “reproductive outcomes” on a par with other behavioral outcomes investigated, such as pregnancy.

During the follow-up survey period, in-depth interviews were conducted with a sub-sample of 25 survey respondents to explore feelings around childbearing and HIV. The interview protocol covered several broad topics: childbearing and family planning (personal experiences and perceptions of community attitudes); experiences around HIV testing; and, for HIV-positive respondents, the impact of the diagnosis on their reproductive lives. An experienced Tanzanian qualitative researcher not affiliated with the health services carried out the interviews in a private room in the clinic. Interviews took place in three rounds of five to ten interviews each. For the first round, respondents were chosen using purposive sampling to ensure a mix of HIV-positive and HIV-negative respondents with various socio-demographic characteristics. For the second and third rounds, respondents were chosen using theoretical sampling, based on preliminary findings from the first round in order to approach theoretical saturation. This made the sampling responsive to emerging ideas. After 25 interviews (including 12 with HIV-positive respondents), it was deemed that a sufficient degree of saturation had been reached.

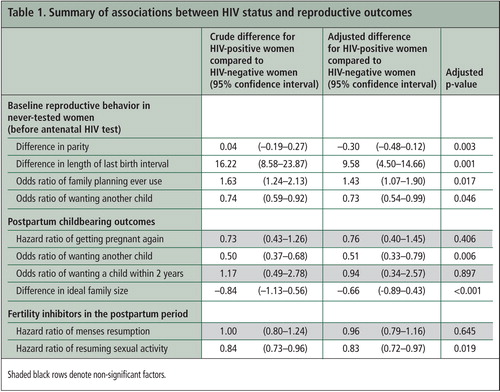

The survey data were analyzed using STATA 11.Citation18 Multivariate linear, logistic and Cox regression was used to model differences in reproductive behavior between HIV-positive and HIV-negative respondents before they knew their status, and then to model the effect of HIV diagnosis on postpartum reproductive behavior outcomes at follow-up, controlling for baseline pre-testing differences. Estimates in Table 1 are adjusted for age, parity, education, residence and marital status, as well as (where appropriate) time sexually active, past contraceptive use, and the following time-varying factors: death of recent child, postpartum contraceptive use, and menses resumption. Results are adjusted for clustering at the clinic level using STATA’s survey (svy) commands. Although the impact of HIV status on postpartum contraceptive use was also examined, this paper focuses on outcomes related to childbearing desires.

The qualitative data were analyzed using elements of grounded theory, with the help of NVIVO8 qualitative analysis software.Citation19 In order to add to the reliability and credibility of the analysis, the first six transcripts were double-coded by a Tanzanian qualitative researcher, and emerging themes were compared with those identified by the first coder.Citation20

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Tanzanian Medical Research Coordinating Committee and from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Ethics Committee.

Findings

Study sample

HIV prevalence was 8.9%, higher than the estimated prevalence in the general female reproductive-age population in this region.Citation1 Respondents ranged in age from 15 to 49, with a median age of 24, and had a mean parity of 1.9 children (range 0 to 12). Respondents were a median 10.5 months postpartum at follow-up (range 6–15). Pregnancy outcomes did not differ significantly by HIV status, with 97% and 96% of HIV-negative and HIV-positive respondents respectively having had a live birth.

The high loss to follow-up between the baseline and follow-up survey (less than 50% of baseline respondents were interviewed at follow-up) could bias findings if women lost to follow-up were different from those followed up with regards to key characteristics. Although we cannot compare characteristics at follow-up, no significant differences in baseline characteristics (including HIV status) were identified between those lost to follow-up and those followed up.

Differences by HIV status before testing

Among women who had never previously been tested for HIV, HIV-positive respondents differed from their HIV-negative counterparts before testing (Table 1) as follows: HIV-positive women had on average 0.3 fewer children (p=0.003), and previous birth interval was nearly 10 months longer after controlling for contraceptive use since last birth (p=0.001). HIV-positive respondents were also slightly more likely to want to stop childbearing than their HIV-negative counterparts (p=0.046) and significantly more likely to have used contraception in the past (p=0.017).

Impact of HIV diagnosis on childbearing desires at follow-up

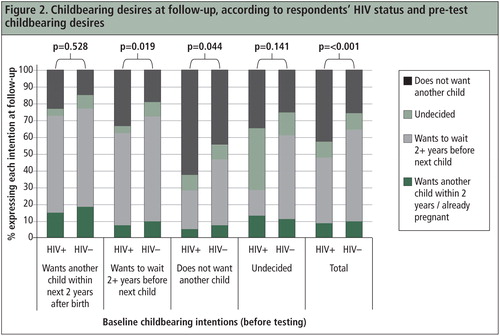

Ideal family size was significantly lower in HIV-positive women, who desired on average 0.7 fewer children than their HIV-negative counterparts (3.9 versus 4.6) (Table 1). The overall distribution of ideal family size was shifted downwards for HIV-positive women ().

HIV diagnosis also appeared to have a significant effect on desire for another child: after adjusting for parity and pre-test childbearing desires, HIV-positive women were half as likely to want another child as HIV-negative women (Table 1). This association was much stronger than the association between childbearing desires and HIV status before testing, and represents the net effect of an HIV-positive diagnosis on childbearing desires, regardless of the previous influence of undiagnosed HIV infection.

HIV diagnosis appeared to decrease childbearing desires through two pathways (). First, it appears to have encouraged women who at baseline wanted to stop childbearing to stick to their desires: 62% of the HIV-positive respondents who wanted to stop childbearing at baseline still wanted to stop at follow-up, whereas over half of the HIV-negative women who wanted to stop childbearing at baseline had changed their minds by the time of follow-up. Second, an HIV-positive diagnosis appeared to discourage women who did want another child before testing from having one: among respondents who at baseline wanted a child, HIV-positive respondents were significantly more likely than their HIV-negative counterparts to decide they did not want one after all by the time of follow-up. However, HIV diagnosis did not seem to affect short-term childbearing desires: there was no significant difference by HIV status in proportions wanting a child within the next two years at follow-up, regardless of respondents’ childbearing desires at baseline (). This was confirmed in a multivariate regression (Table 1). The fact that hazards of getting pregnant during the follow-up period did not significantly differ by HIV status (Table 1) further suggests that short-term childbearing is not affected by HIV diagnosis.

HIV-positive diagnosis was also associated with longer post-partum abstinence (Table 1), even though similar proportions of HIV-positive and HIV-negative women were married, suggesting that abstinence might be used as a transmission risk-reduction strategy. Among both HIV-positive and HIV-negative women, hazards of getting pregnant during the follow-up period and desire for another child at follow-up were significantly associated with younger age, lower parity and being married, while ideal family size increased with age and parity, and was higher among women who were married, rural and less educated.

Factors influencing childbearing after diagnosis: qualitative findings

The qualitative analysis identified several factors that appeared to strongly discourage HIV-positive women from childbearing. The most frequently voiced concern was the increased health risk associated with pregnancy for HIV-positive women.

“The community knows that if a person with the virus gets pregnant and bears a child, her health condition deteriorates and she dies. Considering the condition I have, how would I live if I bear another child?” (Respondent 8, age 35, 5 children, urban, HIV-positive)

“There is no need for her to continue bearing children given that she has problems already, because if she continued bleeding, the problem will be aggravated. She needs to stop [childbearing] completely so her health may be good... She is not supposed to bleed excessively. She needs to use the blood for her health. Now if she gives birth, she will bleed excessively. It is better she stopped and continued living.” (Respondent 21, age 34, 6 children, rural, HIV-negative)

Respondents were also heavily influenced by nurses’ advice, which appeared to be largely directive and dissuasive of them having more children, as exemplified below. The shift in global policy and advocacy in recent years towards a reproductive rights-based approach to reproductive and contraceptive counseling for HIV-positive womenCitation21 was not reflected in the experiences these 25 women described.

“When I got tested and was found to be infected, the nurse advised me not to bear children anymore: ‘If you continue bearing children, you keep on losing strength through bleeding.’ People would be very worried. They might say: ‘This person will die upon delivery.’ ... So my worry in bearing children is the nurse advised me that when you bear children, your health keeps deteriorating... That is my worry. I might give birth and die on the same day.” (Respondent 6, age 31, 5 children, urban, HIV-positive)

“God might bless you and you become pregnant and bear a healthy child, without the child having HIV, and you’d be happy thinking, ‘This child has no HIV... Our days are numbered, therefore if God will bless us and let us continue to live, this is the one who will help us in the future.’” (Respondent 5, age 20, one child, urban, HIV-negative)

Although most of the HIV-positive qualitative study participants thought that it was preferable to stop childbearing after being diagnosed with HIV, the survey results indicate that 47% of HIV-positive women continued to want more children after diagnosis. Several qualitative study respondents cited factors that may encourage women to continue having children after diagnosis. For example, there appeared to be a perception that having HIV prevents a woman from becoming pregnant.

“If her condition does not indicate [she has HIV], they’d say: ‘Wrong things are being said about this person, she is healthy. Had she been infected, why would she be pregnant?’ Those who do not know much about it think that when you get infected, you become so sick and can’t become pregnant, that you’d just be glued to a sickbed. If I become pregnant, these people wouldn’t know that I’m HIV-positive. Even if they knew that so-and-so has been infected, they would doubt it: ‘Mm, it is not true, these are mere rumors, so-and-so is healthy because she’s become pregnant.’” (Respondent 16, age 30, 3 children, rural, HIV-positive)

Interviewer: “If a woman does not have children, how do you think the society will regard her?” Respondent: “They’d say, ‘Gosh! This person doesn’t bear children, she bears poop.’” Interviewer: “What does ‘she bears poop’ mean?” Respondent: “You know, in many homes, if someone gets married and does not bear children, this person would be gossiped about at home: ‘Mr. X, your wife bears poop! Every day she bears poop, we don’t like her. It is better you find someone who can bear a child.’” (Respondent 25, age 41, 8 children, rural, HIV-negative)

“My partner forces me to have children, but I don’t like it, given my condition... He wants to destroy me because he’d want to have a child by force... I have no way out!” (Respondent 7, 39 years old, 2 children, urban, HIV-positive)

Discussion

By focusing on the antenatal and postpartum period, this study provides insight into the impact of HIV diagnosis on childbearing desires. HIV infection appeared to affect fertility even before diagnosis, as seen in HIV-positive women’s lower parity and longer birth intervals. This is most likely due to factors described in other studies: biological effects of HIV such as reduced fecundity and increased fetal loss,Citation15 as well as behavioral effects of undiagnosed infection such as reduced coital frequency due to illness, relationship instability or suspicion of infection.Citation13,14 The fact that HIV-positive women in this study were slightly more likely to want to stop childbearing even before diagnosis suggests that they may have suspected they were infected, and altered their childbearing desires in response. Such a phenomenon has been observed in other African studies.Citation8,13,22

After adjusting for pre-test differences, an antenatal HIV-positive diagnosis was associated with a downward adjustment in long-term childbearing desires, nearly halving the odds of wanting another child. Lower childbearing desires following HIV diagnosis have been found in other African studies.Citation6–10 However, findings from other studies (outside of the postpartum context) have suggested that HIV diagnosis leads women to accelerate their pace of childbearing in the short term relative to HIV-negative women, despite lower long-term desires, perhaps in a bid to reach an acceptable family size while they are still healthy.Citation6,7 In this study, in contrast, HIV diagnosis did not affect short-term desires or the hazards of becoming preg nant again during the follow-up period. We propose that the lack of effect of HIV diagnosis on short-term childbearing desires is specific to the postpartum period: in contrast to HIV-positive women diagnosed outside of pregnancy, women diagnosed during pregnancy may have fulfilled their short-term childbearing desires with their recent birth, and may be more motivated to delay their next pregnancy in order to let their bodies rest. HIV-positive women’s pregnancy desires and concerns may thus be more similar to those of HIV-negative women in the postpartum context than in other contexts.

The decrease in long-term childbearing desires after HIV diagnosis stands out in the context of strong societal pressure to continue childbearing. The qualitative findings suggest that for women who already had several children, economic worries, health concerns (compounded by nurses’ advice to avoid pregnancy), and the uncertain plight of existing children seemed to prevail over the desire to conform to societal norms. HIV infection remained at the forefront of their childbearing considerations, regardless of their current health status or their use or non-use of antiretroviral therapy (although the small number of women on treatment limited our ability to identify differences in that regard). One of the major perceived risks of childbearing appeared to be excessive blood loss, suggesting a poor understanding of the links between HIV infection, pregnancy and blood loss. Women need clear evidence-based explanations of how HIV does and does not affect health and fertility, and also need information about the important role of antiretroviral treatment during pregnancy and beyond.

While HIV was a prominent factor in childbearing considerations, factors such as age and parity still showed a strong influence on postpartum childbearing desires, both in the quantitative and qualitative analyses. This is in line with findings from other studies highlighting the continuing influence of demographic characteristics and societal norms on fertility desires even after an HIV-positive diagnosis.Citation23 The qualitative interview data suggest that pronatalist norms may exert a greater influence on young, low-parity women after diagnosis, highlighting a need for future research to understand the specific reproductive health needs of these women and their partners.

HIV-positive women face a nearly impossible task in trying to comply with conflicting societal and familial expectations of their roles as mothers and HIV-infected individuals, resulting in what Ingram and Hutchinson call a “double bind.”Citation24 These expectations are likely to be particularly problematic for women who are diagnosed HIV-positive before they have had any children, when pressure to prove they are not barren is at its highest. However, community contempt for childlessness is likely to constrain women’s reproductive choices in a multitude of situations, regardless of HIV status. Such views need challenging not just in relation to HIV, but also as part of a wider effort to secure reproductive rights for all women.

In light of the numerous factors that HIV-positive women may consider in childbearing decision-making, it is imperative that antenatal HIV counseling and any subsequent contraceptive counseling take into account each woman’s individual circumstances with regard to her marital status, HIV disclosure status and wider societal expectations.Citation25,26 Other studies have shown that if counselors respond negatively to the prospect of HIV-positive women having children or even being sexually active, this may alienate women who want another child, as well as women who want to use hormonal contraception to avoid pregnancy, potentially resulting in unwanted pregnancies and unnecessary risk-taking with regards to HIV transmission to partners and children.Citation27,28 A woman’s ability and willingness to discuss her pregnancy plans with her health care provider are pivotal to enabling her to access the services she requires. The obvious need to take HIV status into account when providing such tailored reproductive information underscores the rationale for integrating contraceptive and HIV counseling.

In order to provide HIV-positive women with comprehensive support, these integrated services need to be offered on a continuum from antenatal care into the extended postpartum period. The continuum should encompass contraceptive counseling at antiretroviral treatment clinics throughout and beyond the postpartum period, during which time the demand for contraception among HIV-positive women is likely to increase as a result of their lower long-term childbearing desires. Contraceptive counseling in this context will also provide an opportunity to assess potential longer-term effects of antiretroviral treatment on childbearing desires and reproductive health needs, for instance implications of increased coital frequency and fecundity due to improved health.Citation29–32 Furthermore, the changes in childbearing desires between the antenatal and postpartum period (in both HIV-positive and HIV-negative women) emphasize the importance of providing a continuum of reproductive services which are responsive to women’s evolving desires and circumstances, as well as offering non-judgmental support to women who wish to translate these desires into behavior.

While the antenatal/postpartum setting presents a unique opportunity to address HIV-positive women’s reproductive needs, conducting our study in this setting resulted in some limitations. Getting nurses to interview antenatal attendees creates the risk of introducing courtesy bias in responses, since attendees might feel pressured into answering with what they perceive to be health providers’ desired responses. In particular, since nurses serving this study population tended to discourage continued childbearing after HIV diagnosis, HIV-positive respondents may have underreported desire for more children. However, using nurses to conduct interviews in antenatal clinics enabled us to access a large number of reproductive-age women undergoing HIV testing, an advantage judged to outweigh the drawbacks of potential courtesy bias. Such courtesy bias may have been less likely to affect the in-depth interviews, as the qualitative interviewer explicitly told her respondents that she was independent from the health services.

The postpartum period is a propitious time for contraceptive counseling and initiation, since many HIV-positive women wish to limit further childbearing and are still in contact with the health care system through mother and child health clinics. In this context, antenatal HIV counseling offers an important first point of contact for women as they start thinking about their postpartum reproductive plans. Failing to offer women the services they require during this critical period could result in missed opportunities to address their reproductive needs and desires, as well as to prevent unwanted pregnancies.

Acknowledgements

The baseline component of this study was funded by a Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria Round 4 grant channeled through the Tanzania National Coordinating Mechanism. The follow-up survey and in-depth interviews were funded by the Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction, a joint program of the United Nations Development Programme, the United Nations Population Fund, the World Health Organization and the World Bank.

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of all Mwanza research staff involved in data collection for this study: Doris Mbata (who carried out the in-depth interviews), Sarah Gaula (who led the follow-up survey team) and other research assistants without whose support this study would not have been possible.

References

- TACAIDS. Tanzania HIV/AIDS and malaria indicator survey 2007–08. 2008; Dar es Salaam: Tanzania.

- ORC Macro International. Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey. 2005; Calverton, MD: USA.

- JD Gipson, MA Koenig, MJ Hindin. The effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child, and parental health: a review of the literature. Studies in Family Planning. 39(1): 2008 Mar; 18–38.

- HW Reynolds, B Janowitz, R Wilcher. Contraception to prevent HIV-positive births: current contribution and potential cost savings in PEPFAR countries. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 84(suppl 2): 2008 Oct; ii49–ii53.

- J Heys, W Kipp, GS Jhangri. Fertility desires and infection with the HIV: results from a survey in rural Uganda. AIDS. 23(suppl 1): 2009 Nov; S37–S45.

- IF Hoffman, FE Martinson, KA Powers. The year-long effect of HIV-positive test results on pregnancy intentions, contraceptive use and pregnancy incidence among Malawian women. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 47(4): 2008 Apr 1; 477–483.

- F Taulo, M Berry, A Tsui. Fertility intentions of HIV-1 infected and uninfected women in Malawi: a longitudinal study. AIDS and Behavior. 13(1): 2009 Jun; 20–27.

- SE Yeatman. The impact of HIV status and perceived status on fertility desires in rural Malawi. AIDS and Behavior. 13(1): 2009 Jun; 12–19.

- SE Yeatman. HIV infection and fertility preferences in rural Malawi. Studies in Family Planning. 40(4): 2009 Dec; 261–276.

- C Baek, N Rutenberg. Addressing the family planning needs of HIV-positive PMTCT clients: baseline findings from an operations research study. 2005; Population Council: Washington DC, USA.

- B Elul, T Delvaux, E Munyana. Pregnancy desires and contraceptive knowledge and use among prevention of mother-to-child transmission clients in Rwanda. AIDS. 23(suppl 1): 2009 Nov; S19–S26.

- K Peltzer, LW Chao, P Dana. Family planning among HIV positive and negative prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) clients in a resource poor setting in South Africa. AIDS and Behavior. 13(5): 2009 Oct; 973–979.

- W Moyo, MT Mbizvo. Desire for a future pregnancy among women in Zimbabwe in relation to their self-perceived risk of HIV infection, child mortality, and spontaneous abortion. AIDS and Behavior. 8(1): 2004 Mar; 9–15.

- P Setel. The effects of HIV and AIDS on fertility in East and Central Africa. Health Transition Review: the Cultural, Social, and Behavioural Determinants Of Health. 5(suppl): 1995; 179–190.

- A Ross, L Van der Paal, R Lubega. HIV-1 disease progression and fertility: the incidence of recognized pregnancy and pregnancy outcome in Uganda. AIDS. 18(5): 2004 Mar 26; 799–804.

- JA Ross, WL Winfrey. Contraceptive use, intention to use and unmet need during the extended postpartum period. International Family Planning Perspectives. 27(1): 2001 Mar; 20–27.

- E Thomson. Couple childbearing desires, intentions, and births. Demography. 34(3): 1997 Aug; 343–354.

- STATA/IC 11.1. 2009; StataCorp: College Station, TX, USA.

- NVivo8. 2009; QSR International: Australia.

- J Green, N Thorogood. Qualitative methods for health research. 2004; Sage Publications: London.

- WHO, UNFPA. Sexual and reproductive health of women living with HIV/AIDS: guidelines on care, treatment and support for women living with HIV/AIDS and their children in resource-constrained settings. Geneva; 2006.

- Noel-Miller CM. Concern regarding the HIV/AIDS epidemic and individual childbearing: evidence from rural Malawi. Demographic Research 2003; Special Collection 1 (Article 10):320–47.

- B Nattabi, J Li, SC Thompson. A systematic review of factors influencing fertility desires and intentions among people living with HIV/AIDS: implications for policy and service delivery. AIDS and Behavior. 13(5): 2009 Oct; 949–968.

- D Ingram, SA Hutchinson. Double binds and the reproductive and mothering experiences of HIV-positive women. Qualitative Health Research. 10(1): 2000 Jan; 117–132.

- S Gruskin, L Ferguson, J O’Malley. Ensuring sexual and reproductive health for people living with HIV: an overview of key human rights, policy and health systems issues. Reproductive Health Matters. 15(29 suppl): 2007 May; 4–26.

- L Myer, C Morroni, WM El-Sadr. Reproductive decisions in HIV-infected individuals. The Lancet. 366(9487): 2005 Aug 27–Sep 2; 698–700.

- D Asiimwe, R Kibombo, J Matsiko. Study of the integration of family planning and VCT/PMTCT/ART programs in Uganda. 2005; USAID: Arlington, VA, USA.

- R Feldman, C Maposhere. Safer sex and reproductive choice: findings from “Positive Women: Voices and Choices” in Zimbabwe. Reproductive Health Matters. 11(22): 2003 Nov; 162–173.

- H Bussmann, CW Wester, CN Wester. Pregnancy rates and birth outcomes among women on efavirenz-containing highly active antiretroviral therapy in Botswana. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 45(3): 2007 Jul 1; 269–273.

- J Homsy, R Bunnell, D Moore. Reproductive intentions and outcomes among women on antiretroviral therapy in rural Uganda: a prospective cohort study. PloS ONE. 4(1): 2009; e4149.

- M Maier, I Andia, N Emenyonu. Antiretroviral therapy is associated with increased fertility desire, but not pregnancy or live birth, among HIV+ women in an early HIV treatment program in rural Uganda. AIDS and Behavior. 13(1): 2009 Jun; 28–37.

- L Myer, RJ Carter, M Katyla. Impact of antiretroviral therapy on incidence of pregnancy among HIV-infected women in sub-Saharan Africa: a cohort study. PLoS Medicine. 7(2): 2010 Feb 9; e1000229.